Maximising vaccine uptake in underserved communities: a framework for systems, sites and local authorities leading vaccination delivery

Contents

- Overview and purpose

- Approach to driving uptake

- Designing a multipronged approach to drive uptake in low uptake groups

- Identifying priority low uptake communities

- Building partnerships with community organisations and networks to stress-test underlying root causes and devise interventions

- Designing communications-focused interventions

- Designing access-focused interventions

- National resource bank

Classification: Official

Publications approval reference: C1226

Version 1, 26 March 2021

1. Overview and purpose

1.1 This document provides a problem-solving framework, best practice, and practical guidance for implementing a range of interventions to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccination and drive uptake in underserved communities.

1.2 It provides a menu of interventions and choices to increase confidence, improve convenience and tackle complacency. It is not intended to be a comprehensive guide of all interventions that could be deployed, and innovation and adaption are essential to maximise local knowledge and the experience of established partnerships.

2. Approach to driving uptake

2.1 The approach is influenced by three root causes of vaccine hesitancy identified by the World Health Organisation and will support local systems to intensify meaningful and respectful activity in their local communities to improve vaccine uptake and ensure health inclusion:

- 2.1.1 Confidence: low confidence can be driven by lack of information, misinformation or lack of trust in the institution, all of which can be targeted with a range of communications interventions and strategies.

- 2.1.2 Convenience: can refer to ease of access through location of sites and low barriers to access, e.g. transport, booking, opening hours.

- 2.1.3 Complacency: can result from low perceptions of risk, particularly in younger age-groups.

2.2 Within previous UK national vaccination programmes, reported vaccine uptake has been lower in areas with a higher proportion of minority ethnic group populations:

- 2.2.1 Primary care data analysed by QResearch indicates that, for several vaccines, Black African and Black Caribbean groups are less likely to be vaccinated (50%) compared to White groups (70%). Furthermore, for new vaccines (post-2013), adults in minority ethnic groups were less likely to have received the vaccine compared to those in White groups (by 10-20%).

- 2.2.2 Recent representative survey data from the UK Household Longitudinal study shows overall high levels of willingness (82%) to take up the COVID-19 vaccine but with marked differences by ethnicity, with Black ethnic groups the most likely to be vaccine hesitant followed by Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups.

2.3 Current data shows differences in uptake within the first four JCVI priority cohorts, despite overall high level of vaccine confidence and approval in older age groups, with initial data suggesting at a national level that:

- 2.3.1 Black African communities have the highest hesitancy compared to other ethnic groups

- 2.3.2 Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities have higher hesitancy than White British/Irish and Indian communities

- 2.3.3 White non-British groups may have higher hesitancy or increased barriers, e.g. non-English speaking groups

- 2.3.4 Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, people experiencing homelessness and asylum seeker, refugee and migrant populations may need additional routes to access the vaccine

- 2.3.5 Income and socio-economic circumstances correlate with lower levels of uptake

2.4 Identifying and analysing locally the highest priority low uptake groups is essential, and further segmentation of these groups will be necessary to understand the root causes of vaccine hesitancy and devise the most successful interventions to drive uptake.

2.5 For each group identified, a multipronged approach is essential to drive uptake and should include these three themes (See Figure 1):

- 2.5.1 Partnerships

- 2.5.2 Access

- 2.5.3 Communications

2.6 The specific interventions should be designed and adapted locally in partnership with local authorities, community networks, faith groups and community leaders to ensure they maximise local knowledge to target root causes of vaccine hesitancy in all groups identified and use local networks to maximise uptake, e.g. pop up site selection, community leader recruitment for simultaneous communications campaign and distribution of information through the most active channels for each group.

3. Designing a multipronged approach to drive uptake in low uptake groups

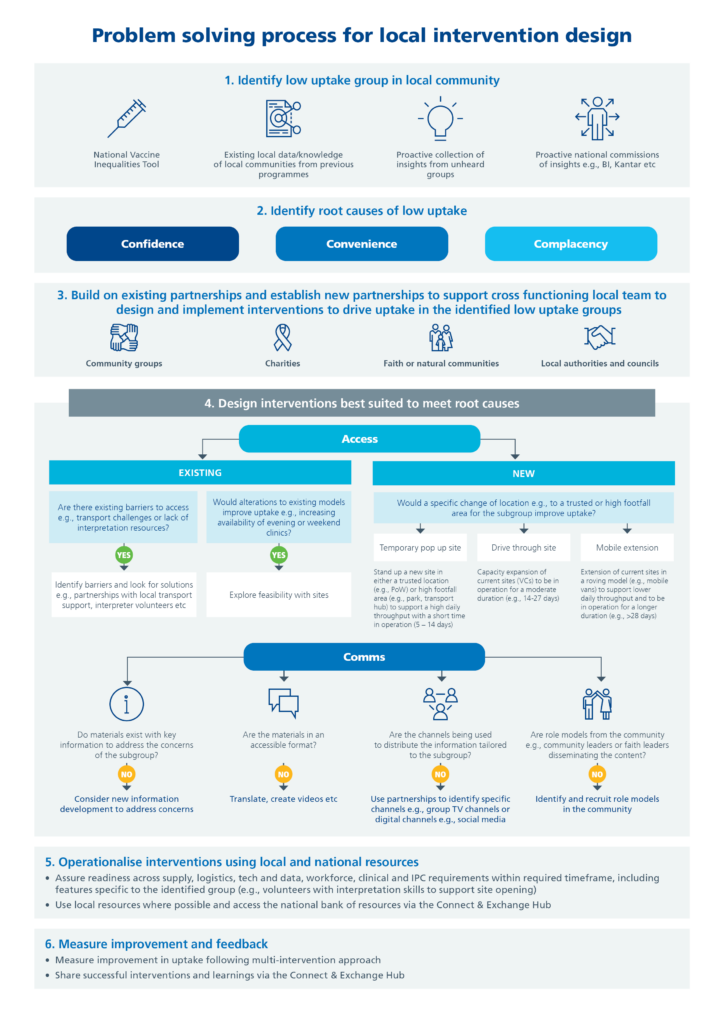

3.1 A problem-solving process for designing successful local interventions is described below. It suggests a multipronged approach to maximise local knowledge, partnerships and understanding when designing interventions.

3.2 This process is designed to engage and involve the community at all stages, including considering participatory research if possible to ensure the approach is built into local processes and structures.

3.3 A mixed methods approach should be taken to measure the improvement in uptake (quantitative) and the impact (qualitative) of the intervention.

4. Identifying priority low uptake communities

4.1 This stage involves analysing data and insights locally to identify priority groups, using national data (e.g. Vaccine Equalities Mapping Tool and insights from the National Programme Demand arm), data from local networks and past public health or vaccination programmes, and qualitative and quantitative data from ‘seldom heard’ populations.

4.2 Segmenting groups even further means communication interventions and changes to delivery models can be tailored to each group’s needs. For example, in the homeless group of cohort 6, identifying those in receipt of a regular prescription means community pharmacies are the most suitable delivery model for this group, and identifying non-English speaking Pakistani Muslims and translating information leaflets and videos into Hindi, Bengali, Urdu, Punjabi to meet their needs.

4.3 Identifying the root cause of low uptake can be achieved by working with the community and determining which of the key themes (confidence, convenience and complacency) apply – this helps to determine which interventions are most needed.

5. Building partnerships with community organisations and networks to stress-test underlying root causes and devise interventions

5.1 Partnerships with local community groups, community leaders, charities and networks are essential to understand the size of the group, the causes of vaccine hesitancy and the tools needed to support the community.

- 5.1.1 Example – Quantify the size of the homeless community in Winchester to ensure sufficient uptake within this group by linking with local high-risk hostels and other local charities, such as the churches in Winchester, and the night shelters that offer temporary dormitory accommodation for street homeless, to request they provide a list of their residents to quantify the cohort size.

- 5.1.2 Example – Engagement with community ‘Boater’ leads in Bristol Swindon and Wiltshire STP to understand causes of vaccine hesitancy in the transient boater community (as members of this community have 10-15 years less life expectancy than average general population). This highlighted the key issue being lack of information and ease of access due to many not being registered with a GP. The engagement led to better understanding of the best channels for information sharing (e.g. a specific Facebook group) and the ability to highlight ‘Boater-friendly’ GP practices in the STP footprint, and to consider pop up clinics near the canal to drive uptake in the future.

5.2 Partnerships are essential to ensure intervention design maximises local knowledge of the group (including root causes of vaccine hesitancy) and uses the local networks to maximise success of interventions and vaccine uptake.

5.3 National partnerships with national charities and organisations are helpful when a particular group is prevalent across the nation, or in a large number of local areas, e.g. younger cohorts or Muslim communities, and can help prevent misinformation by proactively sharing messaging that builds trust and confidence in the vaccine.

- 5.3.1 Example – National partnerships established with third sector organisations (e.g. Indian Muslim Welfare Society, Hindu Council UK, Muslim Council of Britain) to encourage the UK Muslim community to get vaccinated.

5.4 Local level partnerships with organisations, networks and groups specific to the prioritised groups will help you to understand the reasons for complacency alongside other root causes. These partnerships also provide networks that can maximise the success of the communications and access interventions.

- 5.4.1 Example – Work with all existing London partnership networks (Faith, VCS, Business, Arts, Local Economy) to encourage and support network-facilitated conversations on COVID-19 vaccines.

6. Designing communications-focused interventions

6.1 Communications materials should be tailored to each group so they can access reliable, accurate and trusted information. This can include translating materials into different languages and ensuring accessibility requirements are met (e.g. materials available in Braille or audio recordings).

- 6.1.1 Case study – Translated materials for non-English speaking ethnic minority community members in Bristol North Somerset and South Gloucestershire ICS.

- 6.1.2 Case study – Videos produced in Punjabi providing an A-Z guide on the COVID-19 vaccine, including myth-busting. These increased uptake of vaccines in hard-to-reach ethnic minority communities in Nottinghamshire.

- 6.1.3 Case study – Films made with a range of community faith leaders during their vaccination explaining why they chose to be vaccinated and sharing information. This included two Afro-Caribbean community senior leaders encouraging uptake of the vaccine (one CEO and one pastor).

6.2 The channels used to share information can also be tailored to each prioritised group to ensure trust in the institutions and channels delivering the information and to maximise reach.

- 6.2.1 Example – Information shared via Pakistani news network potentially reaching one million viewers in the UK.

- 6.2.2 Example – Webinars delivered in Gujarati to target Jain faith population. This was achieved by working with 32 community organisations under the ‘OneJain’ organisation to deliver several health education webinars via Zoom. The two initial webinars, delivered in Gujarati, received over 25,000 views. These were aimed at elderly Gujarati members of the community who were then invited for COVID-19 vaccination. The webinars included information on COVID-19, how to stay safe, how to manage symptoms at home, how to access the right care and information on the vaccine itself. It included a myth busting segment and a live Q&A session with a panel of GPs, hospital doctors and scientists.

6.3 Role models can also be identified and recruited to share information across channels to drive trust in the information being shared and the institution and networks delivering the information. Role models can be those most relevant to the group, e.g. clinicians or healthcare workers, community leaders, faith leaders or other influencers.

- 6.3.1 Case study – Ethnic minority community and faith leaders are booking people into clinics in the pop-up sites at community centres, temples and mosques to drive uptake.

- 6.3.2 Case study – Using health coaches from the voluntary and charitable sector to target patient groups in a diverse (ethnic minorities and high deprivation) population in West Yorkshire. Secondment of 28 health coaches from the local voluntary and charitable sector into the 90,000 patient PCN, which has a diverse population ranging from very high levels of deprivation and ethnic diversity to rural and more affluent groups. The health coaches were given lists of patients every week who it had not been possible to contact, needed support deciding about vaccination or accessing clinics, or initially declined vaccination. The coaches also promote vaccines within their communities and work with local people and community leaders to address concerns and myths about vaccination.

- 6.3.3 Case study – Nigerian GP and clinicians in Norfolk produced videos of them receiving their vaccine, which were shared across different platforms as a way of informing the public, especially the ethnic minority groups who may be hesitant and have doubts about the authenticity of the vaccine.

7. Designing access-focused interventions

7.1 The convenience and ease of access of vaccination can be a key driver of low uptake. The vaccination timing, location and access requirements (transport, booking, physical space, shape of delivery team, e.g. all female vaccination team) can impact and will be specific to each group.

7.2 Tailoring existing delivery models and sites to make access as convenient as possible is an important first step, for example, increasing out of hours or weekend clinics, and removing barriers to access such as transport or booking challenges (e.g. due to need for interpreter support).

7.3 If access issues are combined with low confidence, then dedicated clinics at existing sites can improve uptake by using local knowledge to connect the location to the community, or increase the visibility or connection with community role models or key opinion leaders.

- 7.3.1 Example – Dedicated clinics for people experiencing homelessness and rough sleeping at an existing vaccination site were held in Brighton which improved uptake.

- 7.3.2 Example – Specific vaccination clinic for patients with learning disabilities organised by the Central Liverpool PCN combining COVID-19 vaccination with completing an Annual Health Check. The clinic was a collaborative effort between the PCN Network and local Learning disability team with medical students trained to perform the Annual Health Checks and administer vaccines, supervised by three GPs.

7.4 If poor access or predicted low uptake are due to the location of vaccination sites, but the number of days required to vaccinate the group are too low to warrant a pop up site in that location, then using mobile vaccination units at the existing site can improve uptake, such as a vaccination bus.

- 7.4.1 Example – Vaccination bus to drive uptake in the Crawley Hindu community. It visited locations across Crawley to encourage uptake within the town’s diverse communities by travelling to specific locations (through partnerships). This increased confidence and uptake of vulnerable patients in the Hindu community.

- 7.4.2 Example – Mobile vaccination unit for homelessness outreach operated across key locations tailored to homeless people in Brighton and Hove through partnerships with a homelessness community group, St John Ambulance, a homelessness charity (Justlife) and the local NHS Foundation Trust. This highlights the importance of partnerships to ensure access.

- 7.4.3 Example – Roving ambulance to increase uptake in high deprivation areas. This offered drop-in sessions in areas of East Brighton by working with public health, LA, NHS, local community and voluntary leaders and local foodbank managers.

7.5 If individuals are unable to reach any vaccination site, then this barrier could be removed by providing transport support.

- 7.5.1 Example – Using community transport infrastructure in the rural Derbyshire Dales to transport elderly and physically disabled patients to a central vaccination site. Local volunteers from mountain rescue teams and community first responders supplemented national volunteers.

7.6 Innovative delivery models can also be tailored to the prioritised group including drive through and pop up clinics in locations particularly convenient or trusted by them (e.g. places of worship or high footfall locations).

7.7 If convenience of access is important to improve uptake, but the number of days required to vaccinate the group is too low to warrant a pop up site in that location, and there isn’t resource (e.g. vehicles) for mobile extension of the existing vaccination site, then extending existing sites using the drive-through model may help.

7.8 If convenience is the main issue, with a significant number of people in the low uptake group meaning multiple days of vaccination are needed, then holding pop-up vaccination sites at trusted high footfall locations can improve uptake.

- 7.8.1 Example – People experiencing homelessness and rough sleeping: In Winchester, temporary vaccination clinics were held at several addresses acting as hostels or shelters to this high-risk group over two full days, with the majority of residents vaccinated.

- 7.8.2 Example – Pop up clinics in three mosques in Dorset ICS (Bournemouth, Christchurch, Poole areas) leading to hundreds of individuals being vaccinated.

- 7.8.3 Example – Pop up clinic at residential location for asylum seekers in inner city Bristol (the Haven Residence). Videos were taken with this group to spread messages to peers.

- 7.8.4 Example – Pop up clinic in a large Pentecostal Church in Bournemouth with high numbers of Nigerian population in the congregation.

- 7.8.5 Temporary (pop up) vaccination site guidance is available here and includes a venue checklist. Prior to launch, readiness must be ensured across supply, logistics, tech and data, workforce, clinical and infection prevention and control requirements within the required timeframe.

8. National resource bank

8.1 The national resource bank is available to access and share materials and guidance to speed up readiness assessment and prevent duplication of effort (e.g. translating materials).

- 8.1.1 Translated materials

- 8.1.2 Temporary site guidance

- 8.1.3 Drive-through guidance

- 8.1.4 Multi-occupancy guidance

- 8.1.5 National resources, e.g. volunteer workforce to free GP capacity to undertake longer visits / phone calls or using military to support housebound visits

8.2 Challenges can be anticipated for specific groups based on their needs. These can be pre-empted and prepared for in advance to minimise the challenges and disruption to efficient vaccine delivery:

- 8.2.1 Missed second dose (e.g. among people experiencing homelessness or rough sleeping). More work will be needed to ensure provision of second doses due to regular location changes. Therefore, multiple visits are required to ensure those that miss the initial first dose and the second dose visits are given another opportunity.

- 8.2.2 Informed consent (e.g. elderly or people experiencing homelessness or rough sleeping) may require longer conversations to ensure the information meets individual needs and that the appropriate capacity assessment is completed and obtained.

- 8.2.3 Local vaccination sites should consider how they can reach people who are housebound or who will require significant support to access services. Recognising the circumstances that contribute to people being unable to leave their homes encompass a range of factors which could include illness, frailty, surgery, mental ill health, lack of practical support or nearing end of life.

- 8.2.4 During lockdown people may have experienced social and health-related changes, others will have lost the support they may previously have relied on. There may therefore be additional individuals who are housebound or unable to access services without significant support and who may not be appropriately marked as such in GP registers.