A new dementia currency in primary care

There has been unparalleled interest in, and awareness of, dementia over the last five years.

This was ignited by the publication of the National Dementia Strategy in 2009, energised by the first Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia in 2012 and fuelled by a raft of developments such as the hospital dementia scheme, the primary care detection initiative, the creation of Dementia Action Alliances across the country, reduction in the prescription of antipsychotic drugs by 50% and the creation of one million dementia friends.

Support for people with dementia was rated in the top five in importance by the NHS Citizen’s Jury in 2015.

For NHS England, the prevailing focus for the last year has been the fulfilment of the ambition that two thirds of the estimated number of people with dementia have a formal diagnosis and post diagnostic support.

The ready availability of the national diagnosis rate coupled with the absence of a corresponding simple metric for post diagnostic support have inevitably resulted in a focus on the former. The successful achievement of the diagnosis rate of 67% at the end of November 2015 has, along with a collective sigh of relief, allowed conversations to move to post diagnostic support and beyond.

Much of the focus has been toward primary care, emphasising the long term nature of dementia, the need to get things right for patients in primary care – including prompt assessment and treatment – and the issue of whether GPs should be empowered to initiate anti Alzheimer medication.

We recognise that primary care is under strain, in terms of workload, and this has been well publicised. There are a number of different models of primary care and dementia and we thought it would be helpful, as a way to stimulate discussion, to describe, from our point of view, three principal challenges for which there may be some solutions.

First, the fear of giving a diagnosis and getting it wrong: The discussions on the role of primary care are not around those patients in whom a memory clinic or specialised neurological assessment is required, but older patients, who are often in care homes, where the presence of dementia and cognitive impairment is but one of a number of long term conditions and may not be the primary reason for concern over specific symptoms.

The aspiration is not to persuade GPs to diagnose dementia but to facilitate information so GPs can feel safe about diagnosing dementia in certain clinical situations. There is a need to empower colleagues to be able to make a diagnosis if they think that is clinically justified and appropriate.

Second, the clinical message of the benefits of a diagnosis: This is around post diagnostic support and five Ps encapsulate the advantages of investigating people with memory problems – discovering treatable emotional and Physical illness; installing Post diagnostic support for carers and families with evidence that this can Prevent crises; emPowering people with dementia and their carers; and finally Prevention of significant cognitive decline with interventions directed towards vascular risk factors.

Third, the way in which dementia is managed in primary care: Many people have drawn the analogy between dementia and other long term conditions, such as diabetes, and we recall a time when diabetes was a specialised diagnosis requiring specialist management but that is clearly no longer the case.

One concern is how cognitive impairment can be appropriately recorded in primary care – perhaps in a similar vein to raised blood pressure. We need to incentivise good practice whereby a person who comes complaining of memory can have some investigations, perhaps some memory advice, and then reviewed in a few months. This is analogous to when someone comes with mildly raised blood pressure.

The ability to refer such a person to get advice over lifestyle and prevention strategies is crucial and a pathway that facilitates this would be important.

The profile of dementia is such that we need to ensure that the appetite to improving the care of people with dementia is ever present.

We suggest:

- Browse the Dementia Primer and its companion to refresh your memory around dementia

- Consider making your practice dementia friendly (write to us if you need more information about how to do this).

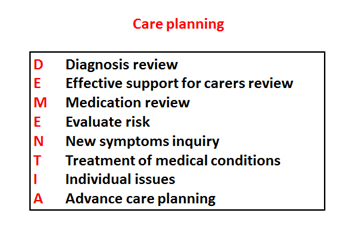

Use the acronym DEMENTIA to guide your dementia reviews:

We would be grateful to hear any comments at Alistair.Burns@nhs.net

- Professor Alistair Burns, is NHS England’s National Clinical Director for Dementia.

- Dr Peter Bagshaw is a General Practitioner at the Willow Surgery, Downend, Bristol, and Clinical Lead for Dementia, South West Strategic Clinical Network.