Pulse oximetry to detect early deterioration of patients with COVID-19 in primary and community care settings – 12 January 2021

Contents

- Introduction

- Identifying patients who can be managed in a primary care setting

- Assessment and monitoring of patients who meet the criteria for management in a primary care setting

- Maintaining safe equipment

C0445

Pulse oximetry to detect early deterioration of patients with COVID-19 in primary and community care settings

12 January 2021, Version 1.1

Introduction

This document sets out principles to support the remote monitoring, using pulse oximetry, of patients with confirmed or possible COVID-19. It should be read alongside the COVID Oximetry @home standard operating procedure, as well as the general practice and community health services standard operating procedures. Updates to the version published on 11 June 2020 are highlighted in yellow so you will know what has changed if you are using this content.

Patients most at risk of poor outcomes are best identified by oxygen levels.1 The use of oximetry to monitor and identify ‘silent hypoxia’ and rapid patient deterioration at home is recommended for this group.

Many practices and community teams already use oximetry to support remote monitoring. The principles set out here will inform this ongoing work and allow national rollout of this model to those patients who are most likely to benefit from this approach. They apply to both patients living in their own homes and residents of care homes. They are designed to support patients in primary and community health settings, and can also be used for patients who are at an early stage of the disease and sent home from A&E or discharged following short hospital admissions.

Identifying patients who can be managed in a primary care setting

In all circumstances, the use of remote monitoring and pulse oximetry is at the clinician’s discretion. This guidance is designed to support clinicians in making this decision, drawing on emerging good practice.

Patients with possible COVID-19 and requesting advice or support should initially be encouraged to use the NHS 111 Online service. The NHS 111 telephone service should be used only when online access is not possible. Some will contact their practice in the first instance and they should be reviewed by their practice and not redirected to NHS 111.

Patients with symptoms of COVID-19 may make direct contact with practices or be referred to practices by NHS 111 and the COVID-19 Clinical Assessment Service (CCAS). If patients present directly to general practice, they should be assessed by the practice rather than redirected to NHS 111, as this poses significant risks to unwell patients.

Exertion oximetry (under the supervision of a clinician) is used to pick up desaturations and for better early identification of those at risk of significant deterioration. It is particularly useful for identifying ‘silent hypoxia’ (low oxygen levels in the absence of significant shortness of breath). It is undertaken in patients with saturations of at least 93% and the most common tests are the 40-step walk and the one-minute sit-to-stand.2

Existing evidence suggests the cohorts that will benefit most are those with:

- A diagnosis of COVID-19: either clinically or positive test result, and are also:

- Symptomatic and are either:

- aged 65 years or older or

- under 65 years and clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) to COVID-19.3

Colleagues are advised to consider carefully the implications before extending the pathway more widely.

Patients with possible COVID-19 should be assessed for alternative diagnoses before remote monitoring of deterioration with COVID-19. They should be given clear advice on what to do if their symptoms deteriorate while on these pathways.

Emergency care via the 999 service is needed where a patient’s condition meets any of the criteria in the red box below, unless the patient has made an advance decision not to be admitted to hospital, in which case they should receive urgent symptom management in community settings.

Attend your nearest A&E

OR if these more general signs of serious illness develop:

If you have a pulse oximeter, please give the oxygen saturation reading to the 999 operator. |

Ring your GP or 111 as soon as possible if you have one or more of the following and tell the operator you may have coronavirus:

If your blood oxygen level is usually below 95% but it drops below your normal level, call 111 or your GP surgery for advice. |

Assessment and monitoring of patients who meet the criteria for management in a primary care setting

Patients should be managed by primary care in accordance with the policies set out in the general practice standard operating procedure.4

Following assessment using the total triage model, plan an assessment using pulse oximetry.

- Ambulatory patients: assess triaged patients on site, in accordance with local protocols adopted to separate patients with and without symptoms of COVID-19 (this could be done using a hot site, hot zone or in an appropriate out-of-hours setting, according to local service set up).

- Housebound or shielding patients: deliver pulse oximeters to patients. As permitted by local supplies, this can achieved by:

- asking a friend or family member to pick up the oximeter in person, and asking the patient to take the test at home

- using a volunteer (referrals for support can be made via the NHS Volunteer Responders portal5) if immediately available.

Depending on the local monitoring model, patients may be contacted. Contact the patient to get their oxygen saturation readings (at rest or, where appropriate, on exertion) or it can be arranged for these to be phoned through. Written instructions for how to use a pulse oximeter and record oxygen saturations are included in the example diary in Annex 2 (published separately), and an NHS video is also available. A video consultation may be appropriate to teach the patient how to use the oximeter. Where patients are reliant on carers to help take measurements, it may be appropriate to support carers to put in place infection prevention and control procedures.

Annex 1 below sets out suggested clinical criteria for determining which patients in the primary care cohort are suitable to be managed using a remote monitoring model.

When remotely managing a patient, the frequency of follow-up should be at the discretion of the clinician, usually the GP. Advice on the frequency of check-ins is included in the COVID Oximetry @home standard operating procedure.

When home monitoring is possible, a diary should be considered (see example in Annex 2, published separately), allowing oxygen levels and function to be captured at the discretion of the clinician. Talk patients through the warning signs that require escalation, and instruct them to contact their clinician if their condition deteriorates. Document the safety-netting advice given.

Maintaining safe equipment

Decontamination: Clean the pulse oximeter between each patient within multi-patient settings and on return from a home care setting, following the published guidance.6

After decontamination equipment returned from residential care settings will need to be checked before it is used again, to ensure it is working correctly.

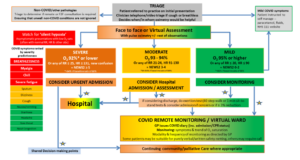

Annex 1 Adult primary care Covid 19 assessment pathway7

Footnotes

1 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2765184

2 www.cebm.net/covid-19/what-is-the-efficacy-and-safety-of-rapid-exercise-tests-for-exertional-desaturation-in-covid-19/

3 The CEV to COVID-19 list should be used as the primary guide. Clinical judgement can apply and take into account multiple additional COVID-19 risk factors. The CEV list continues to be updated in light of the latest

evidence.

4 www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/publication/managing-coronavirus-covid-19-in-general-practice-sop/

5 https://goodsamapp.org/NHSreferrals

6 DHSC: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/877533/Routine_decontamination_of_reusable_noninvasive_equipment.pdf

7 See also: www.cebm.net/covid-19/what-is-the-efficacy-and-safety-of-rapid-exercise-tests-for-exertional-desaturation-in-covid-19/