We are pleased to have worked in partnership to deliver the National women’s prisons health and social care review, which, over a period of two years, has culminated in the development of this important report. We acknowledge the significant achievement of all involved and would like to give special thanks to Jenny Talbot OBE, who fulfilled the role of independent chair of the multi-agency Women’s Review Board. Jenny’s care, leadership and commitment to women in the criminal justice system has enabled all to be heard, with women in prison being front and centre of the Review. We would also like to thank Vanessa Fowler, who directed its work, and Mahala McGuffie and Emma Sweet, who respectively ensured the contribution and perspective of the prison service and women with lived experience were maintained.

The Women’s review was a multi-agency and multi-disciplinary undertaking, at the heart of which were the voices of those with lived experience. Equally important, the Women’s review heard from clinicians and practitioners, commissioners and providers of services, policy leads, the voluntary sector and academics.

We are especially grateful to governors and heads of health care at the 12 women’s prisons who helped facilitate visits, and to health and social care staff, prison staff and residents who spoke candidly of their experiences and offered suggestions for change.

Each of these contributions has helped to shape and inform this report, which sets out eight strategic recommendations for improving health and social care outcomes for women in prison – all of which we accept.

We look forward to continuing our partnership and taking forward these recommendations, underpinned by a clear programme of work for the next three years. Further information on how this will be achieved is set out in section six of this report, noting this work will be overseen by a new Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board. Directing their focus will be the National partnership agreement for health and social care for England that sets out the basis of, and commitment to, the way in which we work with our partners to support the commissioning and delivery of healthcare in English prisons. At the centre of this work will be women in prison, ensuring their views and experiences continue to inform all we do.

Kate Davies CBE, National Director of Health and Justice, Armed Forces and Sexual Assault Services Commissioning.

Alan Scott. Executive Director Public Sector Prisons North and Women’s Estate, HM Prison and Probation Service.

1. Foreword

The National Women’s Prisons Health and Social Care Review was established in 2021, driven by a commitment to improve health and social care outcomes for all women in prison and upon their release.

Women in prison have disproportionately higher levels of health and social care needs than their male counterparts in prison and women in the general population. High numbers of women in prison experience poor physical and mental health and many are living with trauma. Findings from this Review further highlight the vulnerability and adverse life experiences of many women in prison. Mothers feel keenly the separation from their children that imprisonment brings, and women who are mentally unwell are still being sent to prison. None of this is new. Women make up a small proportion (around 4%) of the overall prison population and can sometimes be overlooked in a majority male estate.

At the heart of the Review were the voices of women with lived experience. From initial conception through to writing this report, women with lived experience have been involved at every stage. We are proud of the 2,250 responses received from women in prison and how their contributions have informed this report. The Review also heard from those who provide care and support to women in prison. The strength of these collective views, combined with analyses of data, serves as a model for future work and provides a baseline for HM Prison and Probation Service, NHS England and local authority social care as they implement the strategic recommendations from this report.

A great deal has been learnt from this Review, with women in prison speaking candidly about their experiences and reflections on how services might be improved. What we heard wasn’t easy, but it was considerably more difficult for the women telling us something of their life stories. Women spoke about the need for services that address the root causes of trauma, as well as the symptoms and ‘coping mechanisms’ of substance misuse and self-harm. Mothers spoke of being alone, without support, feeling devastated at being separated from their children and the damage caused to families by the destabilising impact of imprisonment. We heard about the importance of feeling safe in prison and for some, the fear of inadequate support on release and a return to their old lives. Women also spoke of their future aspirations – a place they could call home, of staying ‘clean’ and making a new life.

The way in which health and social care services are delivered is not always gender or trauma informed, reflective of protected characteristics or consistent across the women’s prison estate. Too often, women in prison must access available services rather than services that meet their individual needs. We did, however, find many examples of good practice and thank the dedicated staff who make a positive difference to the lives of women in their care.

We hope and trust that this report adequately reflects all that we have learned and welcome the decision to establish a Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board to oversee the thorough implementation of its recommendations.

We extend our thanks to all those who were involved in contributing towards the Women’s Review and this report.

Emma Sweet, Lived Experience Deputy Expert Advisor, NHS England Health and Justice National Team.

Jenny Talbot OBE, Independent Chair, National Women’s Prisons Health and Social Care Review

2. Executive summary and eight strategic recommendations

‘Women are and have different issues to men in prison. (We) are mothers, carers, home makers, sisters, girlfriends, daughters. Social expectations of women are different. When we make a mistake – shame, guilt and embarrassment is piled on us because we are women, because we ‘should’ know better. These feelings can make us feel so belittled that reaching out for help can be difficult. It is important services understand this better.’

21. The National Women’s Prisons Health and Social Care Review was established by HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) and NHS England in January 2021, supported by the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) with a shared commitment to:

- improve health and social care outcomes for all women in prison and upon their release

- reduce inequalities and

- ensure equity of access to the full range of health and social care services for all women across the women’s estate.

2.2 The Women’s Review was mainly undertaken during the Covid-19 pandemic and was extended to 2023 to ensure all stakeholders had sufficient opportunity to participate.

2.3 The Women’s Review was informed by women with lived experience, led by an independent chair and guided by a multi-agency Board with input from HMPPS and NHS England.

2.4 Governance arrangements for the Women’s Review are shown at section 3.19.

2.5 Methodology for the Women’s Review involved prison visits, stakeholder engagement events, task and finish groups, reviews of expert literature and analysis of documents, and extensive engagement with women in prison.

2.6 The Review received over 2,250 responses from women who told us about their experiences of health and social care services in prison and made suggestions for change. The Review also heard from those who provide care and support to women in prison.

2.7 Evidence gathered during the Review generated eight main findings. These are shown on pages eight to ten, alongside eight corresponding recommendations, which have been presented to and fully accepted by NHS England and HMPPS.

2.8 Further, three overarching themes integral to the eight main findings were identified, which have a bearing on the implementation of recommendations made. These are:

- Partnership and governance

- Communication

2.9 The delivery of these eight strategic recommendations will be overseen by a new Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board, underpinned by a comprehensive programme of work delivered over the next three years. This new Partnership Board will be co-chaired by a woman with lived experience.

2.10 Responsibility for delivery will rest with different stakeholders and require collaboration and a shared ownership approach. Key stakeholders include local authorities, integrated care systems (ICSs), voluntary sector organisations, research partners, women with lived experience, HMPPS and NHS England.

Table of main findings and corresponding strategic recommendations

| Main finding | Strategic recommendation |

|---|---|

|

1. Health and social care services across the 12 women’s prisons are inconsistent, not always gender specific or sensitive to women with protected characteristics. The prison environment is experienced as unfit for purpose by many women and health and social care providers. |

1. Health and social care services for women in prison should be underpinned by an approach that is gender specific, gender compliant, considerate of protected characteristics, personalised, accessible, equitable, and consistent between all women’s prisons. Fabric improvements across the women’s estate should be made, as needed. |

|

2. Acutely mentally ill women are still being sent to prison. Prisons are ill equipped to provide the necessary treatment and care for acutely mentally ill women. There is a gap in mental health services across the range of needs including primary mental healthcare and specialist interventions for women who have experienced trauma, including sexual and domestic violence. |

2. Women who require support with their mental health should be offered timely, equitable access to the most appropriate gender specific treatment interventions and environment. Access to evidence based talking therapies for trauma should be increased, and consistent pathways of care for survivors of domestic abuse and sexual violence ensured. |

|

3. For many women, reception into prison and the early days in custody was traumatic, deeply distressing and bewildering. This was especially the case for mothers separated from their children and pregnant women. |

3. Emotional and practical support should be readily available and accessible to all women upon reception into, and during their early days in custody. Mothers who are separated from their children, pregnant women and young women moving from the children and young people secure estate may require particular support. |

|

4. The availability and quality of data that describes and informs women’s Health and Social Care Needs Assessments (HSCNAs), and the quality and outcome reporting of services women receive requires improvement. England based research on the health and social care needs, services and outcomes for women in prison is limited. |

4. A co-produced gender specific HSCNA, performance and outcomes framework should be developed, and data collection of health inequalities enhanced. |

|

5. Most women coming into prison require medication. Medicines management, especially around communication with women and between healthcare and prison staff requires improvement. |

5. Improvements are needed in medicines management and communication with women about their health and social care. Reasonable adjustments should be made for women who are neurodiverse, and information should be accessible for women whose first language is not English. |

|

6. The national substance misuse service specification is not gender specific. |

6. The national substance misuse service specification should be refreshed to meet the specific needs of women across the care pathway. |

|

7. Improvements have been made in pregnancy and perinatal care and social care support for women who have been separated from their children, but more needs to be done to drive forward meaningful change. |

7. Improvements in pregnancy and perinatal care, and social care should continue, including support for women who have been separated from their children. |

|

8. The period leading up to release from prison is emotionally challenging for many women and often based in fear. Resettlement services provided by prison, probation and health and social care providers should be better integrated. Having somewhere safe and decent to live on release remains the greatest priority for many women. Where RECONNECT services were available, women spoke highly of them. |

8. Release planning for all women in prison should be integrated across health, social care, prison and probation services. Continuity of support on release, including access to RECONNECT services should be provided in line with women’s release plans. |

3. Background and introduction

How prison health and social care is commissioned

3.1 Since 2013, NHS England has been responsible for the commissioning of healthcare services in prisons across England. It commissions a range of providers from both the NHS and independent sector to deliver healthcare services, including primary care, dental, pharmacy, secondary care mental health services and substance misuse services. Local authorities are responsible for the commissioning of social care and health visiting services in prisons, and integrated care boards are responsible for commissioning secondary care hospital services for people in prison.

3.2 HMPPS is responsible for supporting the operational delivery of health and social care services within prisons and the settings in which care is delivered.

3.3 A National Partnership Agreement between NHS England and HMPPS and other departmental partners provides a collaborative framework between partners, setting out their roles and responsibilities. There are three agreed high-level ambitions, which are to:

- reduce health inequalities.

- reduce reoffending

- improve the continuity of care for patients.

3.4 This partnership is demonstrated at a local level by Prison Health Partnership Boards, which are multi-partner meetings held in each prison and chaired by the prison governor/director. Meetings discuss and report on the delivery of health and social care in the prison and include the experience of those who receive services.

Profile of women in prison

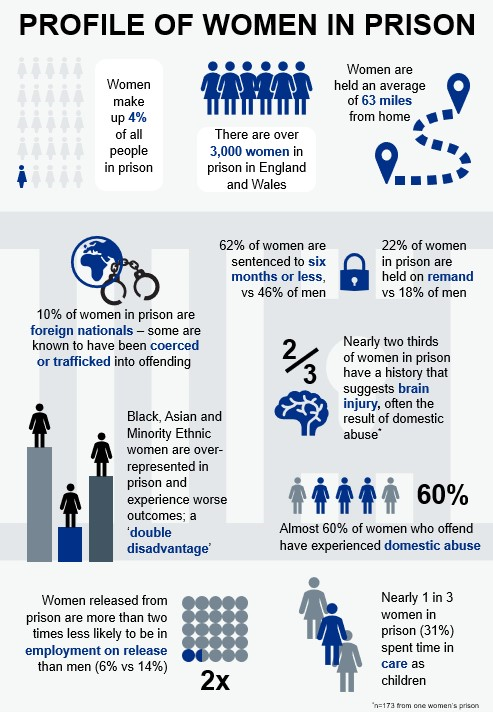

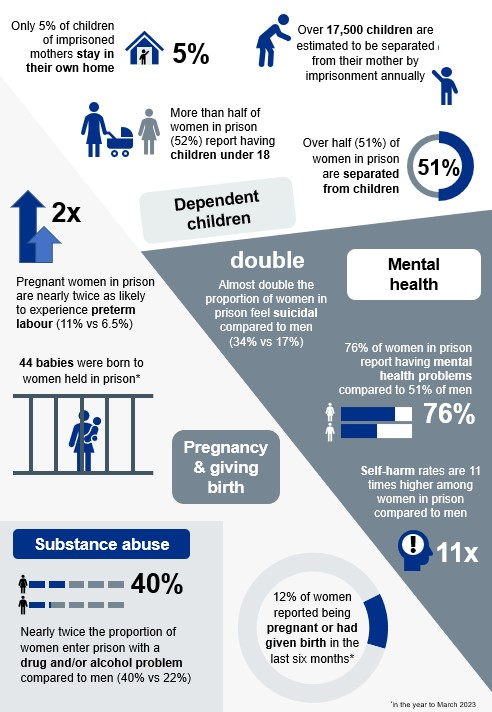

3.5 Women make up 4% of the overall prison population and their particular needs can sometimes be overlooked in a majority male estate.

3.6 The profile of women in prison and their unmet health and social care needs are well documented. See infographic at Appendix two.

About the women’s review

3.7 The National Women’s Prisons Health and Social Care Review was established by HMPPS and NHS England in January 2021, with a shared commitment to:

- improve health and social care outcomes for all women in prison and upon their release

- reduce inequalities

- ensure equity of access to the full range of health and social care services for all women across the women’s estate.

‘You come to prison… you’re anxious, worried, scared, you don’t know what’s going to happen next and the nurses ask you a load of questions and the officers rush you through – no one really cares about what’s really going on.’

3.8 Improving health and social care outcomes for women in prison requires strategic and operational cooperation and understanding and collaboration between health, social care and prison services and staff.

3.9 The Women’s Review has been informed by women with lived experience, led by an independent chair and guided by a multi-agency Board with input from HMPPS and NHS England. The outcome of the Review is set out in this report.

3.10 The Women’s Review was mainly undertaken during the Covid-19 pandemic. During this time, women in prison were experiencing a reduced regime, a reduced ability to access a range of health and social care services, reduced contact with their family and a longer amount of time in their cell/room. This, combined with reduced staffing levels due to sickness, created challenging circumstances for all involved, and impacted opportunities for prison visits and, crucially the ability to engage with women in prison. Consequently, the duration of the Women’s Review was extended by a year to 2023, to ensure that women in prison and the health, social care and prison staff who work with them had sufficient opportunities to participate. It should be noted that undertaking this Review during such a challenging period may have influenced responses received from all stakeholders and therefore may not be a true representation of experiences outside of the pandemic.

3.11 The Women’s Review supports the strategic aims of the Female Offender Strategy (2018) and, more recently the Female Offender Strategy Delivery Plan 2022 to 2025 (2023). The Delivery Plan commits to fewer women entering the justice system and serving short custodial sentences, with a greater proportion managed successfully in the community. Professor Dame Carol Black’s independent review of drugs (2021) similarly notes that alternatives to custody and community sentences should be the first line of response. Women’s centres offering local interventions can offer real opportunity for alternatives to custody by playing a key role in meeting women’s needs within their own communities.

3.12 However, it is also recognised that prison can provide an important and much needed opportunity for women to engage with health and social care services, both during their time in prison and upon their release.

‘The things I have done don’t bear thinking about – I got that drug psychosis, some very strange things going through my mind. I think prison has saved my life. I felt hopeless when I came here. I thought I’m never going to get my kids back, that I’m not going to see them while I’m here, but the family worker has been brilliant and given me some hope. I felt like I had no hope, but I have that now and that’s what I’m focusing on, I couldn’t see any way out, but I can see that now. I’ve got a lot to fight for.’

Methodology

3.13 A range of methods were used to gather evidence for the Women’s Review.

3.14 Seven ‘task and finish’ groups were established to explore specific topics/themes (see Table 1). A lived experience steering group was set up and met regularly to guide the lived experience element of the Review. Each women’s prison was visited at least once. Stakeholder engagement events were held involving professionals and practitioners from health, social care, HMPPS, voluntary sector services and women with lived experience. A literature review was undertaken and analyses of data, including Health and Social Care Needs Assessments, inspection outcomes and related strategy and policy documents, were conducted. This ‘blended’ approach to the methodology is a main strength of the Women’s Review and serves as a model for future work.

Task and finish groups

- Early days in custody (reception, first night and induction)

- Resettlement

- Health and social care needs assessment

- Clinical models, performance and quality

- Prison perinatal care

- Substance misuse

- Fabric and environment from which healthcare and social care services are delivered

3.15 Underpinning the work of the Review was what may be the largest ever engagement of women with lived experience of prison. Over 2,250 contributions from women were received, spanning views captured from group discussions and one to one meetings, letters, postcards and drawings.

‘This is the thing – we’re more likely to talk to you than fill out a form. Come and see us so we can chat about what works and what doesn’t.’

3.16 Contributions reflected the diverse profile of women in prison, including protected characteristics and the full range of sentence types and length. Importantly, a feedback loop has been established to ensure that women know the results of their engagement.

‘It is vital that we utilise the power of lived experience voices to their fullest potential. Hearing from women with lived experience about how services can better meet their needs and build on their strengths, is likely to be more effective and efficient than services designed without their unique insight. This Women’s Review has lived experience embedded throughout, from the voices of women in the prison estate, through to the board. This is an exceptional example of how to correctly involve experts by experience, ensuring impressive outcomes for all.’ Women’s Review Board Member with lived experience

3.17 During the engagement process, women were asked what their priorities were for health and social care. These priorities are shown below.

Women’s priorities for health and social care

- The quality and effectiveness of services from a patient perspective

- Gender specific services, including reproductive health

- Access to services

- Support for mental health and emotional wellbeing

- Dignity, privacy and respect

- Feeling safe

- Effective communication, individually and prison wide

3.18 The Women’s Review was mindful of the related health and social care activities, research and enquiries being undertaken by statutory and voluntary sector services across the women’s estate. Where relevant, these were drawn on to ensure convergence and minimise the risk of duplication.

Governance

3.19 The Women’s Review set up a multi-agency Board under the scrutiny of an independent chair, with reporting lines and oversight from regional and national commissioning and strategy groups. Membership of the Women’s Review Board included women with lived experience, clinicians, prison governors, and representatives from probation, HMPPS women’s directorate, public health, voluntary sector services and NHS England.

Limitations

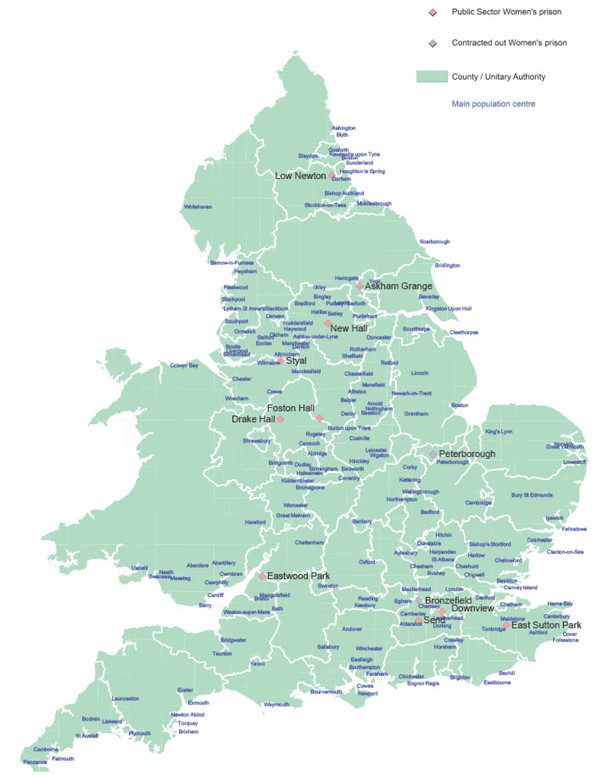

3.20 There are no women’s prisons in Wales, which means that women who live in Wales are detained in prison in England. Healthcare in women’s prisons is the responsibility of NHS England and social care is the responsibility of the individual local authority within which the prison is located. Health and social care in Wales are devolved, therefore different arrangements must be made for the continuity of health and social care for women returning home to Wales. NHS England, HMPPS and the Welsh Government are working closely together to ensure that women returning home to Wales are able to engage with the necessary services. The Women’s Review did not address pathways of care for women returning home to Wales, and further work is needed to address this limitation.

4. Main findings and corresponding strategic recommendations

There are eight main findings that reflect the evidence gathered during the Women’s Review. Each main finding has a corresponding strategic recommendation that is shown at the end of each section. The eight main findings and strategic recommendations are shown together on pages eight to ten.

4.1 Main finding one: Health and social care services across the 12 women’s prisons are inconsistent, not always gender specific or sensitive to women with protected characteristics. The prison environment is experienced as unfit for purpose by many women and health and social care providers.

‘I went to four different prisons throughout and each healthcare (service) doesn’t have consistency, so it’s all very different. Either they would deal with things very quickly or it can get delayed, so there should be consistency throughout prisons. My main concern was about my medication.’

‘I personally would not knock healthcare, I had symptoms of a blood clot, they immediately put me on blood thinners and got me an outpatient appointment for a scan.’

4.1.2 The Women’s Review found wide variation in health and social care services across the women’s estate.

- Whilst there were dedicated and committed staff delivering services in challenging circumstance, these were inconsistently offered and delivered.

- Around one third of women said healthcare services were ‘OK’ and over half (60%) said they needed improvement.

- Most women (69%) said they were treated with dignity and respect.

- Health and social care needs specific to women in prison are not always assessed and responded to, which means that some women in prison have unmet, gender specific needs, such as menopause, incontinence and menstruation.

‘Not one person has spoken to me about incontinence, menopause, what are healthy bowel habits, my boobs. Maybe if we spoke more about these things, women would be able to talk about them and feel more confident to come forward.’

‘Managing your periods in prison can be a nightmare. Some women don’t even know the pill or coil can help. They just assume because they’re in prison, they aren’t entitled to this sort of help.’

‘No one asks, but (incontinence) is a bigger problem than women want to admit. It’s embarrassing. Women are lining their mattresses with sanitary towels.’

4.1.3 Women in prison have access to out-patient secondary care. In 2019/20, 45% of women did not attend their appointments, compared to 22% in the general population. The reasons for this are complex and include the appointment being cancelled by, or on behalf of, the patient; the patient not attending with no advance warning given; or the appointment being cancelled or postponed by the health care provider (Nuffield Trust, July 2022).

Good practice: HMP Styal has visiting health screening services, including breast screening, x ray and ultrasound screening. Women often prefer the less traumatic experience of onsite appointments, which are also less reliant on operational limitations.

4.1.4 Inequalities experienced by women in prison are significant and often intersectional.

- The Women’s Review welcomes the report, Tackling Double Disadvantage (2022), which considers the intersectionality between ethnicity and being a woman in prison.

4.1.5 Women with protected characteristics spoke of the additional hurdles they experienced at being able to access support and, where available, valued specific services.

‘It is not the done thing to be a Muslim woman and admit to a drink problem… But as a Muslim, Asian woman admitting I needed help was hard… Services did nothing to encourage me to get help. It’s like they don’t understand.’

‘No one really knew… until (the Khidmat Centre) came along and introduced Muslim Women in Prison, but before there was nothing for women from different cultures or different races or anything like that.’

‘Being Black and LGBT is hard in prison. No one understands you. There’s no one to talk to who’s like me. It’s lonely sometimes.’

- Neurodiversity was frequently raised as being inadequately understood. Neurodiverse women are not routinely identified, are often misunderstood and sometimes poorly managed. Communication by staff with women with neurodiverse needs is often not delivered in a way that enables and supports understanding and retention. This can result in depression and anxiety, and behaviour such as self-harm, violence and poor regime compliance.

- National learning disability improvement standards have been developed for NHS trusts and private providers that help to measure the quality of care provided to people with learning disabilities and autistic people, and plans are in place to apply these in women’s prisons.

‘We’re a complex bunch. You know there’s a young girl here – ADHD, mental issues, drug user, the lot. Everyone thinks she’s a nightmare, plays up a bit, but really, she’s just a vulnerable girl who needs a lot of support.’

- For many foreign national women, language barriers impacted effective communication and sometimes impeded access to services.

‘There’s a lady here, barely speaks a word of English, she can’t do anything because no one understands her… she doesn’t do anything and could not write out a healthcare app if she needed them. She doesn’t understand the officers or anyone.’

4.1.6 Some women were unhappy and/or unwilling to be seen by male health and social care staff, especially those who had experienced abuse by men, and for cultural reasons.

‘As women, we have had bad experiences with men, for example, domestic violence, rape, and do not trust men at all. I need some help with this, though nothing is available.’

4.1.7 Whilst medication was consistently raised by women, it is important to note that it was rarely seen as a suitable ‘stop gap’ in helping women feel better whilst waiting to be seen by clinical services.

‘Handing out anti-depressants like they’re sweets isn’t going to solve the problem. Investing in counselling, activities, post-natal exercise, wellbeing services is. Even drop-in clinics, or focus groups, support groups would help. Being met with the wall of silence is deafening and extremely depressing.’

- Women wanted to take part in activities, have access to green spaces and to be active. This confirms the importance of social care prescribing as part of the NHS Long Term Plan commitment to making personalised care business as usual.

- Women said they find interventions such as art, singing, yoga, outdoor activities and gym helpful.

‘If we can do group activities more often, please? They don’t do activities, but I think it could help people with mental health issues if they could.’

‘Park runs have been good in the past, really use the outside space, the fresh air, gives us those feel-good feelings.’

Good practice: A social prescribing pilot at HMP Drake Hall offers six interventions including access to ‘pat animals’, yoga and acupuncture.

4.1.8 A stakeholder engagement event, led by the Association of Directors of Adult Social Care (ADASS) was held to discuss arrangements for social care. Priority areas were identified, which included:

- consistency of approach for social care assessments, including self-referral, referral by family members and referral by health and prison staff

- timely notification of transfer between prisons of women with identified social care needs

- timely social care input into resettlement plans

- the development of guidance for social care staff on addressing the social care needs of women in prison and preparation for release, including links with the resettlement team and children’s services, as needed.

Good practice: Mary arrived in custody with reduced function, pain and scarring in her dominant arm and a head injury. She was in a shared ‘dormitory style bedroom’ with three other women and struggled with daily living tasks, memory and understanding the impact of the head injury. Following a social care assessment, Mary was transferred to a single accommodation pod which provided her own room / space with ensuite shower, WC facilities and aids. This enabled her to shower and dress independently in her own time.

The occupational therapist liaised with the mental health occupational therapist at the prison and together sourced support from the local Headway Group (a national charity for brain injury), who were able to provide information to staff to help them support Mary. A wipe board was also provided for Mary to write herself reminders rather than scribbling notes on her hand, which she was doing previously. Mary reported that the support she had received had been very helpful.

4.1.9 The importance of support from social workers to address and assist women with matters concerning caring responsibilities and family liaison work was raised.

- Pilots of dedicated Prison Based Social Workers (PBSW) are exploring the commissioning of the role through local authority and voluntary sector employment. The pilots are being run at four of the 12 Women’s Prisons. They are being well received and producing positive outcomes for women and their families.

4.1.10 In April 2022, a 30-month research programme began to examine the social care needs of women in prison. Undertaken by Manchester University and involving women with lived experience, the research seeks to provide a comprehensive evidence framework to inform the provision of social care for women in prison.

4.1.11 Many women, prison officers and health and social care staff said that the 24 hour nursed care areas are not equipped to meet the complex needs of the women in their care.

- This can often lead to officers and healthcare staff feeling powerless to deliver the care and treatment women need.

- The provision of 24 hour nursed care requires a particular focus. The function of these units has evolved differently across the women’s estate and their development hasn’t been based on any clear strategy or specification. Consequently, they are unevenly distributed geographically and vary in the facilities and care which they offer, resulting in an inequity of service provision.

4.1.12 Many women said that prison and the prison environment had a negative impact on their health and wellbeing.

- The prison environment is important to women as it affects their motivation to achieve optimum health and well-being.

- For neurodiverse women, the environment can have a significantly negative sensory impact.

The prefabricated residential Plymouth and Richmond units were not suitable for use and were damp and mouldy. The problems had been highlighted for about the previous 15 years and, although some cosmetic refurbishment had been undertaken to improve the shower areas, the units remained poor.

(HMIP Report 2020: HMP Drake Hall).

4.1.13 Most women’s experiences of health and social care ‘spaces’ was poor.

‘It isn’t very private. When you’re waiting in the waiting room you can hear people talking in the nurses’ room that’s located in the waiting area even with the door shut.’

‘It’s unclean and smells. The waiting room is awful with writing on the walls.’

- A smaller number of women had a different experience.

‘When you have a doctor’s appointment the waiting room makes you feel like you’re not actually in prison. It’s welcoming and a calm environment just like any doctor’s waiting room outside of prison.’

4.1.14 Women with social care needs, including reduced mobility, women who are neurodiverse and older women appeared most disadvantaged by a poor environment. Improving access to green spaces and social prescribing was cited as highly desirable.

‘It would be nice if more prisons catered properly for wheelchair prisoners, such as ground floor, larger rooms, access to a disabled toilet and a shower we can use. I would like to be able to access all aspects of the regime in closed prisons, and maybe one day an open prison that has disabled access for wheelchair prisoners.’

‘You’ve got more chance getting around prison on a flying carpet than you have in a wheelchair.’

Strategic recommendation one

Health and social care services for women in prison should be underpinned by an approach that is gender specific, gender compliant, considerate of protected characteristics, personalised, accessible, equitable, and consistent between all women’s prisons. Fabric improvements across the women’s estate should be made, as needed.

4.2 Main finding two: Acutely mentally ill women are still being sent to prison. Prisons are ill equipped to provide the necessary treatment and care for acutely mentally ill women. There is a gap in mental health services across the range of needs including primary mental healthcare and specialist interventions for women who have experienced trauma, including sexual and domestic violence.

‘There are so many mental health ladies and ladies with learning disabilities that should not be here! The prison is not a mental health hospital. Staff are not trained to deal with the complex needs, so those people do not get help to do anything or get what they need.’

4.2.1 A main concern repeatedly highlighted by women and staff was the significant challenge faced by women living with and caring for women with mental health problems and neurodevelopmental needs.

- This was especially so for women sent to prison with acute mental illness, women awaiting transfer to hospital and women experiencing a mental health crisis.

‘I had never been so scared in all my life. All the banging and clanging, the shouting. I will never in my life forget the shouting. I felt like the shouting was all directed at me that first day, but now I know they were just ill and there’s always shouting.’

- Around one-third (32%) of women said mental health services were ‘OK’ and over half (57%) said they need improving – a main concern being lengthy waiting times.

- Some women valued the support they received, describing mental health teams as kind, compassionate, understanding and supportive.

‘My mental health worker really helped me understand things and for the first time really validated how I was feeling.’

4.2.2 Working in conjunction with the Women’s Estate Self-Harm Task Force, the Review identified an ongoing challenge in supporting women who self-harm.

- As a consequence of this insight, a whole system, bespoke service specification for women who self-harm is being developed and co-designed with women with lived experience.

‘Some women have only ever known pain, that is their life. They don’t know how to live without it so hurt themselves to make them feel better. Getting help for mental health is a joke.’

4.2.3 Women talked openly about adverse childhood experiences and exposure to trauma prior to prison.

- The Review found a lack of evidence based talking therapy services for trauma, without which, addressing the root cause of many women’s distress and consequent behaviour is not possible.

‘One nurse said, when I self-harmed ‘stop it, where’s it going to get you?” They do not understand the root of the problem. It is not a case of me saying “Oh OK then I better stop, I hadn’t realised it wasn’t getting me anywhere.” It is not trauma informed. They don’t really know what they are doing.’

- Support available for survivors of sexual and domestic violence frequently did not meet women’s needs.

‘I never met a counsellor or a therapist in prison. Women that have been victims of domestic abuse, abused, lost their children, and there is nothing in place for them like therapy. There should be safe spaces where they can open-up, either group therapies or 1-2-1 sessions, or alternatives to help us get it out – writing, art, or gardening. There is nothing like this in prison, those small things that help us feel better.’

- Placing support workers and specialist interventions into each of the 12 women’s prisons will help ensure that domestic and sexual violence is part of everyday enquiry with access to the right help and support.

4.2.4 The view that prison is a ‘place of safety’ for people experiencing a mental health crisis persists.

- We welcome provisions made in the Mental Health Bill which seeks better outcomes by not sending people to prison when they are acutely ill. We further welcome the on-going development of community alternatives to custody, such as Mental Health Treatment Requirements, especially when supported by women’s centres.

- For women who experience a mental health crisis while in prison, ongoing pursuit of the transfer to hospital under the Mental Health Act time targets will continue to be monitored by NHS England and reported against by each prison.

Good practice: Providers at HMP East Sutton Park have come together to integrate mental health and substance misuse care and treatment planning for women. The Forward Trust hold joint reviews and multi-disciplinary team care planning meetings with mental health professionals for shared clients.

Strategic recommendation two

Women who require support with their mental health should be offered timely, equitable access to the most appropriate gender specific treatment interventions and environment. Access to evidence based talking therapies for trauma should be increased, and consistent pathways of care for survivors of domestic abuse and sexual violence ensured.

4.3 Main finding three: For many women, reception into prison and the early days in custody was traumatic, deeply distressing and bewildering. This was especially the case for mothers separated from their children and pregnant women.

‘I didn’t know where I was, I didn’t feel like I could ask, I felt completely away from everything. When they told me, I didn’t have a clue, I couldn’t picture it, then I found out I was hours from home and it really hit me how far away from my kids I was.’

4.3.1 Women said they felt scared and frightened on entry into prison and needed more emotional and practical support, particularly when separated from their children or pregnant.

‘The car was at the court, the kids needed to be picked up from school. It didn’t cross my mind I’d end up in prison. I was in complete shock, my immediate thoughts went to the kids, the car, my job, my mum.’

- Almost half (48%) of women expressed concern about their children, for whom they are predominantly the primary carers for, and described the anguish of separation.

- Women often felt rushed during the reception process and many were reluctant to discuss urgent needs with people they didn’t know or trust.

‘Actually, when I have asked, I have ended up getting the help after a wait, but it’s getting to the point of asking for it. I have to build up that trust and that’s hard in prison.’

- Around half of women said their immediate healthcare needs were met during the first 24 hours in custody.

- The availability of peer mentors in reception received high praise from women, but their roles aren’t consistently available across the 12 prisons.

‘A lot of the real reception work here is done by other women, and it really works for everyone. They get to hear the women’s real needs and they advocate for them if there is a problem.’

- Access to basic provisions for daily living requirements was inconsistent.

- Staff did not always ask women how they felt or explain what would happen next. Information on how women could access health and social care services in reception or first night centres was not always visible or accessible and communication with women about access to medicines and the reasons for any delays or changes was inconsistent.

- Information about women entering custody, for example from liaison and diversion schemes and the Prisoner Escort Record, was not always available or accessible to healthcare.

4.3.2 Some women described feeling vulnerable and unsafe.

‘(I was) traumatised, terrified, alone, shocked, could not stop crying, darkest place mentally, intimidated, no care, support, control, voice, not told hardly anything, confusion, shame, guilt, regret, complete living nightmare, like I could not see an end in sight, hell on earth, total fish out of water.’

- Other women had a different experience, and some spoke of feeling safe, compared to life before prison.

‘I was unsure what to expect but everyone made me feel at ease.’

‘I finally felt safe knowing that there were people who cared, they treat me with respect. I felt safer in prison than in the community.’

Good practice: The early days work undertaken by the Women’s Review provided practical ideas for improvement-based interventions that women with lived experience and practitioners in prison identify as being of benefit. For example, implementing a refreshed trauma informed Reception Screening Tool through to placing a map of England and Wales in reception so that women can see where they are.

Good practice: HMP Peterborough provides a peer led induction process. A detailed range of information is provided (and available in different languages) with the peer worker living on the induction wing to ensure women who may be in shock/find it difficult to remember or process the information given can be supported on a one-to-one basis.

Strategic recommendation three

Emotional and practical support should be readily available and accessible to all women upon reception into, and during their early days in custody. Mothers who are separated from their children, pregnant women and young women moving from the children and young people secure estate may require particular support.

4.4 Main finding four: The availability and quality of data that describes and informs women’s Health and Social Care Needs Assessments (HSCNAs), and the quality and outcome reporting of services women receive requires improvement. England based research on the health and social care needs, services and outcomes for women in prison is limited.

‘Really what I’m seeing here is a system that asks the prisons or healthcare how things are but doesn’t really think about us. We should really be a much bigger part of how our needs are assessed.’

4.4.1 Most of the available prevalence data for physical and mental health conditions is based upon cross-sectional snapshots from HSCNAs.

- These data are only compared to that for other women’s prisons, limiting the ability to understand how the health and social care needs for women in prison compare to women in the general population.

- HSCNAs are not gender specific, and few mention menopause, menstruation and continence. The focus is often on describing services available in prison as opposed to the unmet need or experience of women.

- Women in prison often felt disconnected from the HSCNA process and believed they had much to offer. From their perspective, the focus was on data and evidence from healthcare providers and lacked meaningful engagement with the women themselves.

‘What is the point of a report telling us that 100 women have accessed a doctor, and there’s x number of women waiting to see one, but not asking whether the doctor is any good?’

‘Well, we can see that the people doing these (HSCNAs) don’t really have to ask prisoners about the different topics do they? They should be told that’s what they have to do, so they can really see what’s what.’

4.4.2 Given the limitations of data, including a lack of research focused on the health and social care needs of women in prison, it was not possible for the Review to establish how women experience particular inequalities and subsequently whether different groups of women experience services differently or have different outcomes.

- Only age and ethnicity characteristics are routinely recorded on health records data, with some limited information on disability and religion also available. Other characteristics are not routinely recorded in a way that can be used to interrogate health and social care data.

- Women on short sentences and on remand may not be offered the same access to services as women on longer sentences. (The proportion of women being sent to prison to serve short sentences has risen. In 1993, one third of custodial sentences given to women were for less than six months; in 2022 it more than half (53%) (Ministry of Justice (2023)).

‘Going through numerous short sentences rather than one longer one meant there wasn’t enough time to get any treatment programmes or care plans in place.’

- Existing research is often hampered by a lack of routinely collected, gender specific information.

- Enabling access to relevant IT systems is critical in better supporting the patient pathway, particularly during a woman’s early days in custody and preparation for release. This will be supported by the implementation of the refreshed Clinical IT System GP2GP during 2023, which is already in use across the male estate.

Strategic recommendation four

A co-produced gender specific Health and Social Care Needs Assessment, performance and outcomes framework should be developed, and data collection of health inequalities enhanced.

4.5 Main finding five: Most women coming into prison require medication. Medicines management, especially around communication with women and between healthcare and prison staff requires improvement.

‘This woman also suffers with psychosis and has been taken off Olanzapine, which has meant some of her psychosis is returning. The consequences for her are rocking and pulling her hair out, it’s scary as shit.’

4.5.1 The Women’s Review identified several areas of concern relating to medicines management, the primary one being poor communications. Other areas included:

- delays in receipt of medication on arrival into prison and changes to medication during early days in custody

- difficulties in securing hospital prescribed medication and limited availability of over-the-counter medication

- timeliness of medication and limited opportunities for ‘in possession’ medication

- women being unable to get to the pharmacy, medication queues and potential for victimisation, and medication trading between women

- insufficient medication on release from prison, lack of continuity of prescribed medication, and problems with pre-registration of women with a community GP.

The above concerns are explored in more detail in the rest of this section.

4.5.2 Different approaches to medicines management and variation across the 12 women’s prisons was one of the most highly reported concerns of the Women’s Review.

- Nearly all women coming into prison require medication. Often this relates to substance misuse, pain management and mental health, as well as underlying physical health conditions, such as diabetes.

- Understandably, women are anxious, particularly on arrival and during their early days in prison, about whether they will receive their medication when they need it and that it will be equivalent to the medication they received in the community.

- Healthcare services should be aware of the gender specific healthcare and medicines needs of women, such as Hormone Replacement Therapy and the implications of medicines use in pregnant women.

- Health care providers must follow rigorous governance procedures to ensure safe prescribing of medicines, which women in prison and prison staff are generally unaware of. For example, on a woman’s entry into prison, this involves liaising with the relevant community services and carrying out medicine’s reconciliation prior to dispensing, which can cause delays. It is not always possible for women to continue with the same medication they received in the community and where this is the case, appropriate alternatives will be supplied. These situations require explanation, both for the women concerned and the staff who work with them.

- Some women experience a gap in treatment, which is the period between a women’s entry into prison, when medication prescribed in the community is removed from her and the time when medication is dispensed in prison. The revised Reception Screening Tool and roll out of a refreshed Clinical IT System, GP2GP, during 2023, which allows transfer of information from community health services to the prison, should assist in these situations.

‘It’s a shock when they say, you can’t have that (medication), no one really takes the time to explain, it’s just stopped – the withdrawal can be hard.’

4.5.3 Women reported not being given enough information about the dosage and side effects of their medication. This was particularly, but not exclusively so, for women who are neurodiverse and where English was not their first language.

‘I don’t understand what I’m taking, no one tells me. You’re just expected to pop the pills they give you.’

‘I didn’t understand what the doctor meant. He tried to put me on these tablets, but didn’t tell me what they were for, so I stopped taking them.’

4.5.4 At some prisons, women reported having to queue or wait outside to collect medication and wanted a better system that ensured privacy and confidentiality, reduced the risk of exploitation, protected them from the weather and was more comfortable.

‘Sitting outside can be a pain, there is a shelter but no proper seating but a wall. It’s cold and uncomfortable and we wait at least 20 minutes a day some 2 to 3 times a day.’

‘Everyone knows what meds you’re on because the meds queues are a mess.’

4.5.5 The timeliness of medication, especially at night was a problem for many women. Where in-possession medication is appropriate and secure in cell medication safes provided, this challenge was better managed and experienced by women and staff.

‘Night-time meds are sometimes given at 3-4pm. What good is that? They need to be given at bedtime (quetiapine, zopiclone etc). You sleep all evening then are wide awake at 1am.’

Good practice: HMP Eastwood Park promote in possession medication for women who can manage their medications. Women are encouraged to raise and request medication reviews with the pharmacist to ensure that they understand their medication and are on the correct medication.

4.5.6 The provision and continuity of prescribed medication by prison healthcare on release is reported by many women as a challenge, while others felt well served by healthcare.

‘Getting signed up with a GP took over a month and I went without medication. This happened to me whilst living in so called ‘supported accommodation’ specifically for women leaving prison. This should not have been this difficult!’

‘It was ok for me. Healthcare were good, they asked if I needed help seeing a GP and sorted out my meds until I saw a doctor.’

Strategic recommendation five

Improvements are needed in medicines management and communication with women about their health and social care. Reasonable adjustments should be made for women who are neurodiverse, and information should be accessible for women whose first language is not English.

4.6 Main finding six: The national substance misuse service specification is not gender specific.

‘There’s a lot to do when you’re trying to get straight, but instead of helping us with the abuse we’ve had – they literally just want you to stop taking drugs. No one spoke to me about any of that stuff.’

4.6.1 There is a gap in substance misuse service provision for women whose substance misuse is driven by past trauma, which can impact their experience of these services and health outcomes.

- Substance misuse services in prison should offer interventions that address the underlying trauma that often leads to substance misuse. This is recognised in the From harm to hope strategy (2021), which reaffirms a shared approach between HMPPS and NHS England to deliver improvements to substance misuse services in prison.

‘There needs to be a combined approach, mental health is massive in addiction, but there’s no counselling, you have to explain things again and again which traumatises you further. They treat the addiction – never the root cause, that’s why a lot of us relapse and end up back inside.’

- A bespoke substance misuse service model specifically for women should be developed. This would consider the root causes of women’s substance misuse, focus on harm reduction, reflect sentence length, and include pathways for women with complex needs.

- Women appreciated lived experience in drug and alcohol teams and, in some instances, felt inspired by them, which motivated them during treatment.

‘It’s nice to know they (women with lived experience) can relate to stuff, not saying the others aren’t decent, but it can be the thing that makes you think – if they can do it, I can too.’

- Strengthening links with community provision on release is important, as is creating an environment and support system that helps women stay ‘recovery safe’.

- Recovery communities should be designed with the active involvement of women with lived experience and robustly evaluated to understand their effectiveness.

Good practice: The accelerator pilot substance misuse lead at HMP New Hall and the substance misuse provider deliver quarterly awareness raising health promotion fairs. During the fairs, women can visit stalls provided by prison substance misuse providers and local statutory and voluntary community services (several of which are lived experience led) to encourage engagement with services both in custody and upon release.

Strategic recommendation six

The national substance misuse service specification should be refreshed to meet the specific needs of women across the care pathway.

4.7 Main finding seven: Improvements have been made in pregnancy and perinatal care and social care support for women who have been separated from their children, but more needs to be done to drive forward meaningful change.

‘I wanted to try (breastfeeding) because they told us on the course that it’s good for bonding with the baby, but it was in a small room (in the hospital) and I had two officers sitting right there… so I just gave him a bottle. I tried him on the breast when I got back here (to the prison) a few days later but he didn’t take to it.’

‘Coming to prison and pregnant is the scariest thing I’ve ever been through. Nothing prepared me for it. I had zero idea what to expect. I kept thinking, were they going to take my baby away? Would I ever see him again when he was born? It’s silly, but I constantly held my tummy thinking I could protect him from everything that was happening around me. No one could give me the answers I needed. No one could tell me it was all going to be OK.’

4.7.1 Women who are in prison and pregnant are a high-risk group.

- They frequently experience increased vulnerabilities of their physical and mental health and are at greater risk of perinatal mental health difficulties.

- Not all pregnancy outcomes are positive, with pregnancy loss and separation from babies / children causing trauma to women.

- The deaths of Baby A (HMP Bronzefield) and Baby B (HMP Styal) were tragic events, with HMPPS and NHS England determined that such deaths must never happen again. A robust programme of work, reflective of these sad cases, continues to be delivered and reported on by these two organisations to help drive improvements for the care of pregnant women in prisons.

- The Review found that improvements had been made in perinatal care since these two deaths, with additional welfare checks for all pregnant women and improved support from midwifery and social services.

‘I’m really, really happy with the care that I’ve got, it’s more than I expected.’

4.7.2 The Review found variable approaches to information sharing and provision of services available for pregnant women, including pregnancy testing, health visiting services and referrals to specialist midwives.

‘At the point of risk of prison, women should be given information about pregnancy and prison, even if they don’t disclose they are pregnant.’

- Some women described not knowing about mother and baby units (MBU).

‘I was going to get an abortion – I didn’t know about MBUs. A few weeks in, healthcare came over and said we needed to get me ready for an MBU board. I was like ‘OMG, can I keep my baby?!’

- Opportunities for pregnant women to be involved in the development of pregnancy and perinatal services was variable and underdeveloped. This will be addressed by the implementation of the National service specification for the care of women who are pregnant or post natal in detained settings (NHS England, 2022).

- Providing evidence-based programmes that can be offered to women in the perinatal period to mitigate risks, including parenting classes will also be of benefit and welcomed by the women. Women spoke about the value of meeting with other mums, to share concerns and ideas.

‘We can chat and get out our frustrations. I think talking with other women has really helped build bonds between the women. It would be nice to meet properly once a week so there’s a network for us mums.’

- Emotional support should be routinely available for women who experience the physical and emotional impact of a pregnancy loss through miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, and neonatal death, or who decide to access a termination, or whose children are taken into care.

‘This is worse than the first time I had to leave the baby, this is worse than the trial. I have no help, no support, no counselling. I was put on a list for some service by the chaplain, but the waiting list is long, there is no help for women like me who are about to lose their children to social services.’

4.7.3 The Review identified initiatives that are supporting improved care and experience for women.

- A new training module on pregnancy, mother and baby units and maternal separation has been developed, which all prison officers working in the women’s estate will complete to ensure a baseline level of understanding.

‘I talked to the listeners as I was struggling to cope being away from him (her baby). They told me to tell the officers and from there I got the support I have now, a family worker and she’s really helpful.’

- A pregnancy mother and baby liaison officer role has been introduced by HMPPS into all women’s prisons to support timely identification, contact and signposting to support services. Positive relationships between staff and women in prison are key to supporting women who are pregnant and in enabling them to make informed choices. Training for staff is crucial as women told us how important it is to get the right information and support at the right time.

‘An officer came and told me my baby had died; I was really upset but the officer didn’t really know what to say.’

Good practice: At HMP Peterborough, NHS England commissioned Birth Companions to operate a peer support workers scheme, which supports women to identify and engage with services while in prison. Birth Companions operate focus groups once a quarter, which enable women to share their views. Findings are shared with NHS England and the relevant healthcare provider for action.

Strategic recommendation seven

Improvements in pregnancy and perinatal care, and social care should continue, including support for women who have been separated from their children.

4.8 Main finding eight: The period leading up to release from prison is emotionally challenging for many women and often based in fear. Resettlement services provided by prison, probation and health and social care providers should be better integrated. Having somewhere safe and decent to live on release remains the greatest priority for many women. Where RECONNECT services were available, women spoke highly of them.

‘You’re vulnerable when you come out of prison, people get to you – all your old circles, ex-boyfriends. The pull to that when there’s nothing else is strong.’

4.8.1 Getting resettlement ‘right’ for women will help ensure that health and social care gains made while in prison are protected. Women struggle to prioritise their health when they are homeless or placed in unsuitable accommodation.

‘If a woman has not got a safe place to lay her head and recover from her trauma, she is likely to fail – in every way.’

- Women spoke about a lack of emotional and practical support prior to leaving prison and the need for more proactive sexual health services to discuss pre-conception advice and contraception.

- Women described not being given support to help access health related financial benefits, for example, Personal Independence Payments.

- Nearly 40% of women described experiencing a decline in their mental health immediately upon leaving prison. Simultaneous freedoms, responsibilities and expectations can feel overwhelming. Contributors to poor emotional wellbeing, include the stigma and impact of imprisonment, alongside inadequate accommodation, concern about personal safety, trauma, difficulties accessing medication, challenges rebuilding relationships and a return for some women back into negative relationships.

‘Most of us get released homeless. If you are released homeless, you go back to your old friends and drug use.’

- A small number of women said they had managed to access residential rehabilitation following prison. These women felt particularly grateful for the support they were offered by residential rehabilitation services, yet there was a gap in the offer of this provision in many women’s resettlement plans.

‘When I left prison to go to the rehab centre, they came and picked me up from the gate and took me straight to rehab. If I had needed to make my own way there, I wouldn’t have made it, I would have relapsed on the way. Having her there to meet me was crucial.’

4.8.2 Being assured of safe and secure accommodation on release from prison remains one of the greatest concerns for many women.

- Safety was a big concern for some women, with 25% reporting feeling unsafe when they left prison.

- Women accessing drug or alcohol treatment services repeatedly advised how they perceived unsafe accommodation contributing to relapses.

‘I was sent to an AP (approved premises) with other drug addicts and prison leavers – it was hard to get away from that life and I ended back in jail.’

4.8.3 Continuity of support integrated between prison, probation, health and social care is vital for ongoing safety and reducing mortality risks. Women who do not receive adequate through the gate release planning and support, are at greater risk of harm, reoffending and returning to prison.

- Access to specialist services, dedicated to supporting women through the gate is inconsistent.

‘I had days when I was feeling I can’t wait to go home and once I’m home I’m going to start building my life up again. I had this feeling in my head that whatever needs sorting, I will sort it all out. I’ll get a job, help my kids, I’ve been away from them for so long, but later when I got released, I basically crashed. My mental health went to its highest because I didn’t realise that life was completely different when I came out compared to what I’d left… life was very difficult after prison.’

- Women on short sentences and on remand felt the release planning they received was inadequate. The release of women who are pregnant dictates a requirement for improved links with community maternity services.

‘It was quite quick, they just spoke about my meds, said I’ll have a week’s worth ready for when I leave, no one asked me how I was, and reality was, I was shitting myself about leaving.’

4.8.4 Health and social care services in the community and in prison should routinely work together to help women plan for their release in a way that is person-centred, inequalities aware and trauma informed.

- RECONNECT services will be available across the 12 women’s prisons by March 2024.

‘I think it makes all the difference. They (RECONNECT) can meet people in prison – because otherwise I might not have bothered. When I was withdrawing, RECONNECT met me and gave me the confidence I needed to stick to the detox. This little bit of support, you need it – so you do not feel so alone. I would not have got to where I have without their support. They set me up with MIND, drug and alcohol services, benefits, the job centre, housing, signed me up to a GP, helped with legal stuff and court. I could not have done it without them. I have a little part time job, I’m talking to services to help me stay clean and sort out my mental health, I would have never thought I’d get there.’

Good practice: HMP Eastwood Park initiated an ‘unplanned release project’ in response to the high number of unplanned releases. This project assessed the process of managing unplanned releases and identified points of intervention to ensure that the whole system of healthcare (pharmacy, GPs, nurses and recovery workers), including clinical and psychosocial substance misuse, kicks into action to ensure that a woman is released safely in the community.

Strategic recommendation eight

Release planning for all women in prison should be integrated across health, social care, prison and probation services. Continuity of support on release, including access to RECONNECT services should be provided in line with women’s release plans.

5. Overarching themes

5.1 During the Women’s Review, three overarching themes were identified that are cross cutting and integral to the main findings and have a bearing on the implementation of the eight strategic recommendations. These are:

- partnerships and governance

- communication

- workforce

Partnerships and governance

5.2 To ensure that women’s health and social care needs are prioritised and properly met, it is important to create a strategic oversight mechanism for the women’s estate. In collaboration with NHS England and HMPPS, a Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board will be established to better coordinate and ensure that the distinct health and social care needs of all women in prison are recognised and met. Membership of the Board will include women with lived experience as equal partners and will be co-chaired by a woman with lived experience.

5.3 This structure will oversee delivery of the eight strategic recommendations in this report – the first task being to set clear milestones and tangible outcomes. Integral to the work of the new Partnership Board, will be the development of a Women’s Prisons Learning Network where good practice, lessons learnt, quality improvement journeys and new developments can be shared to improve health and social care outcomes for all women in prison.

5.4 During the Review, concerns were raised that the social care needs of women are often lost to the health agenda and that a focused approach to addressing social care needs would correct this imbalance. To help address this, a National Social Care Implementation Group will be established that will report to the new Partnership Board. This will help to ensure that the social care needs of women in prison are properly met.

5.5 We welcome the Female Offender Strategy Delivery Plan 2022–25 (2023) and the reference to the Women’s Review. We look forward to working with colleagues in agreeing next steps for implementing our eight strategic recommendations to improve health and social care outcomes for all women in prison.

Communication

‘I didn’t get what it all meant, even the words they use don’t make sense, how can I possibly make anything better if no one explains it to me?’

5.6 Communication was a prominent theme arising from engagement with women in prison. In particular:

- Most women said that communication with health and social care staff should be improved, such as in relation to service availability, waiting times, medicines need and arrangements, applications, test results and appointments.

- Women wanted greater and more meaningful opportunities to discuss their health and social care needs both individually and more generally, and to provide feedback and suggestions for improvement – which is in line with trauma informed practice.

- Raising awareness through health promotion activity was also suggested, for example through posters, leaflets and discussion groups.

‘I think there needs to be more help around women’s health issues. I think it would be ok for someone to come on to wings to talk to women about issues.’

- Women explained how poor communication negatively impacts their confidence in care, care itself and patient satisfaction.

- Some women felt excluded from decisions that directly affected them. The quote below describes an experience relating to a woman and her child.

‘They did everything without me, I wasn’t privy to conversations, it was like I didn’t exist.’

- Women described feeling anxious due to poor communication around their health and social care needs.

- Women unable to read and write very well, neurodiverse women and foreign national women are likely to be especially impacted by poor communication.

‘Not all women can use the kiosk. The kiosk is everything. I feel for the women who just can’t use it, because they can’t spell or understand things very well. Sometimes they need help, or it’s not explained properly, but where we haven’t been out (due to Covid), no one can help them.’

5.7 Effective and timely communication between health, social care and prison staff was also raised during the Women’s Review. In particular, prison officers would benefit from a better understanding of arrangements for medicines management and referral routes into services.

Workforce

‘I think this establishment are very good at listening and understanding the women’s needs. They act promptly in a person centred approach.’

‘The staff here are good, healthcare work hard and try their best. You feel looked after and that people care.’

5.8 Workforce is a huge, shared challenge for health and social care providers and for the prison service, with vacancies at an all-time high. The shared aspirations and visions for the women’s estate can only be delivered with sufficient staff, adequately trained and supported to implement the changes and improvements that this report recommends.

5.9 The Review found that not all staff have undertaken or are consistently trained in trauma informed care. Awareness training is important so that staff are better able to understand the impact of prior life experiences on women’s current behaviour and motivation, and to respond appropriately.

‘Officers don’t always get it, sometimes how they talk to us makes it worse. They need better training; they need to learn how to see it when a woman is in crisis. They see us every day, but they see a woman play up and see her as a problem, rather than try and support what is actually going on for her.’

‘I’m lucky, my key worker is brilliant and has helped me get a job to get me out of my cell and always has time for me. Gym staff give as much support as they can. Chapel have helped in Covid so much as well.’

5.10 NHS England’s Health and Justice Inclusive Workforce Programme continues to raise the profile of health and justice careers, facilitate the employment of people with lived experience, promote equalities and promote innovative commissioning practice that encourages workforce development and career progression. Attracting and retaining health staff has been problematic over the years and this has resulted in an over reliance on expensive agency staff, who may not be familiar with working in prison or the importance of a trauma informed approach.

5.11 Post Covid, HMPPS has been re-establishing regimes across the prison estate. During this time, significant challenges have been experienced concerning staff recruitment and retention. In the women’s estate, the extent of the challenge has been more acute in some prisons, including HMPs Foston Hall, Eastwood Park and Styal. Action is being undertaken to address staffing shortfalls, but the impact continues to be felt across many prisons, including access to health and social care.

5.12 The chaplaincy service was cited by many women as being a valued source of support, especially during their early days in prison. Women spoke about support being consistent, non-judgemental and coming from individuals they felt able to trust.

‘The chaplaincy are very good with family matters and will come in to check on us every day.’

‘The chaplaincy are the ones who provided me the most support. I’ll be forever grateful for them.’

‘I trust the chaplaincy; they have been there for me for a long time.’

5.13 The voluntary sector brings with it a workforce with a fresh perspective and an approach that women with lived experience repeatedly tell us is trusted and they have confidence in, particularly as many of the staff have relatable lived experience. Further developing the longevity of funding opportunities and role of the voluntary sector in women’s prisons will serve to assist in gaining additional positive engagement and experiences for women in prison and also assist in addressing workforce challenges.

‘St Giles family worker / support have been amazing with me. I can’t thank the ladies enough.’

‘Birth Companions used to do a pregnancy group once a week, which was about yoga, breathing and just chatting to other women, which was good.’

5.14 The proposed Women’s Prisons Learning Network and NHS England’s Health and Justice Inclusive Workforce Programme will help to ensure a current and future workforce able to deliver improved health and social care outcomes for all women in prison.

6. Next steps from NHS England and HMPPS

6.1 Following publication of this report, a new Women’s Health, Social Care and Justice Partnership Board will be established, co-chaired by a woman with lived experience. Membership of the Board will reflect health, social care and justice, women with lived experience and the voluntary sector. The role and purpose of this new Board will be to oversee the delivery of the eight strategic recommendations made in this report and accepted by NHS England and HMPPS, underpinned by a comprehensive programme of work that will be delivered over the next three years. This will be considerate of the three aims of the Review, as well as the three overarching themes arising from the engagement undertaken. The new Partnership Board will be operational this year, 2023/24.

6.2 With an upward trajectory in funding to support the women’s criminal justice care pathway, this positive growth in investment will enable the development of an enhanced health and social care model for the women’s estate, informed by the eight main findings and strategic recommendations contained in this report. This will be co-developed with commissioners, providers, partners and importantly women with lived experience.