Purpose of this support tool

Breathlessness is a common presenting symptom in primary care with numerous causes. A delayed or inaccurate diagnosis means people don’t get the treatment they need and can end up in hospital unnecessarily.

Early and accurate diagnosis is critical to ensure the best outcome for the patient.

The main aim of this support tool is to align clinical practice in primary care with guideline recommendations in order to provide high-quality care, optimise patient outcomes and reduce unwarranted variation for patients across England.

This guidance is not intended to override clinical judgment in individual cases.

The focus for this pathway support tool is chronic breathlessness presenting in primary care – for acute and sub-acute breathlessness, also see Scenario: Acute and subacute breathlessness, NICE.

Scope of the problem

Breathlessness is a subjective, distressing sensation of awareness of difficulty in breathing.

Breathlessness is associated with high healthcare use, accounting for 5% of presentations to the emergency department (1, 2), approximately 4% of GP consultations (3) and reported by patients in 12% of medical admissions (4).

Breathlessness is reported by around 9-11% (5, 6) of the general population, varying with severity, socioeconomic status (6, 7) and increasing with age to 25% in people over seventy years old (8, 9)

Functional impairment from breathlessness, measured using the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale is associated with reduced survival regardless of underlying diagnosis (10)

Yet despite the burden of breathlessness to the individual, the healthcare system and society, as a whole, delays to diagnoses and misdiagnoses commonly occur.

Delays in diagnosis/misdiagnosis

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- 58% of patients with COPD presented with respiratory symptoms for over 5 years prior to diagnosis (15)

- 42% presented with severe disease (15)

- For those with a label of COPD, the diagnosis is incorrect in 27% (16)

Heart failure (HF)

- 41% presented with HF symptoms in the five years prior to diagnosis (17)

- Only 24% diagnosed with HF followed correct diagnostic pathway with BNP/echo (17)

- 79% were diagnosed during an acute admission in hospital (17)

Interstitial lung disease (ILD)/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Median delay in diagnosis of 1.5 years from initial presentation (18)

- Saw >3 specialists before a correct diagnosis of ILD was made

- 55% were misdiagnosed before the correct diagnosis was made

Overarching principles

Patients without a diagnosis for chronic breathlessness need an objective assessment including a face to face consultation to enable physical examination.

There is rarely a single cause of breathlessness, therefore, multiple investigations are likely to be required and a holistic approach needed.

From the initial presentation, self-management advice for breathlessness should be provided, lifestyle issues addressed, and support for mental health provided where appropriate.

Timeliness is key to avoid the current long delays in diagnosis and treatment; the majority of patients should receive a diagnosis and comprehensive management plan within six months of presentation to the health service.

If a diagnosis and management plan are not in place after initial investigations, a longer consultation may be required for a more detailed history and/or specialist advice.

Patients may not highlight their breathlessness repeatedly and therefore a proactive approach to reassessment is encouraged.

Common or important causes of breathlessness

Cardiac

- Heart failure

- Angina/ischemic heart failure

- Valvular heart disease

- Cardiac arrhythmias

Respiratory

- COPD

- Asthma

- Intestinal lung disease

- Breathing pattern disorder

- Lung cancer

- Pulmonary vascular disease

Mental health

- Anxiety

- Depression

Other

- Obesity

- Physical deconditioning

- Anaemia

- Long COVID

Over 2/3 of breathlessness is caused by cardiorespiratory disease. (8, 11a, 11b)

50% of breathlessness in adults over 40 years old is caused by heart failure, COPD, obesity, anaemia, anxiety, or depression. (12,13)

The aetiology of breathlessness is multifactorial in about 1/3 of patients. (14)

Diagnostic pathway for patient presenting with chronic persistent breathlessness

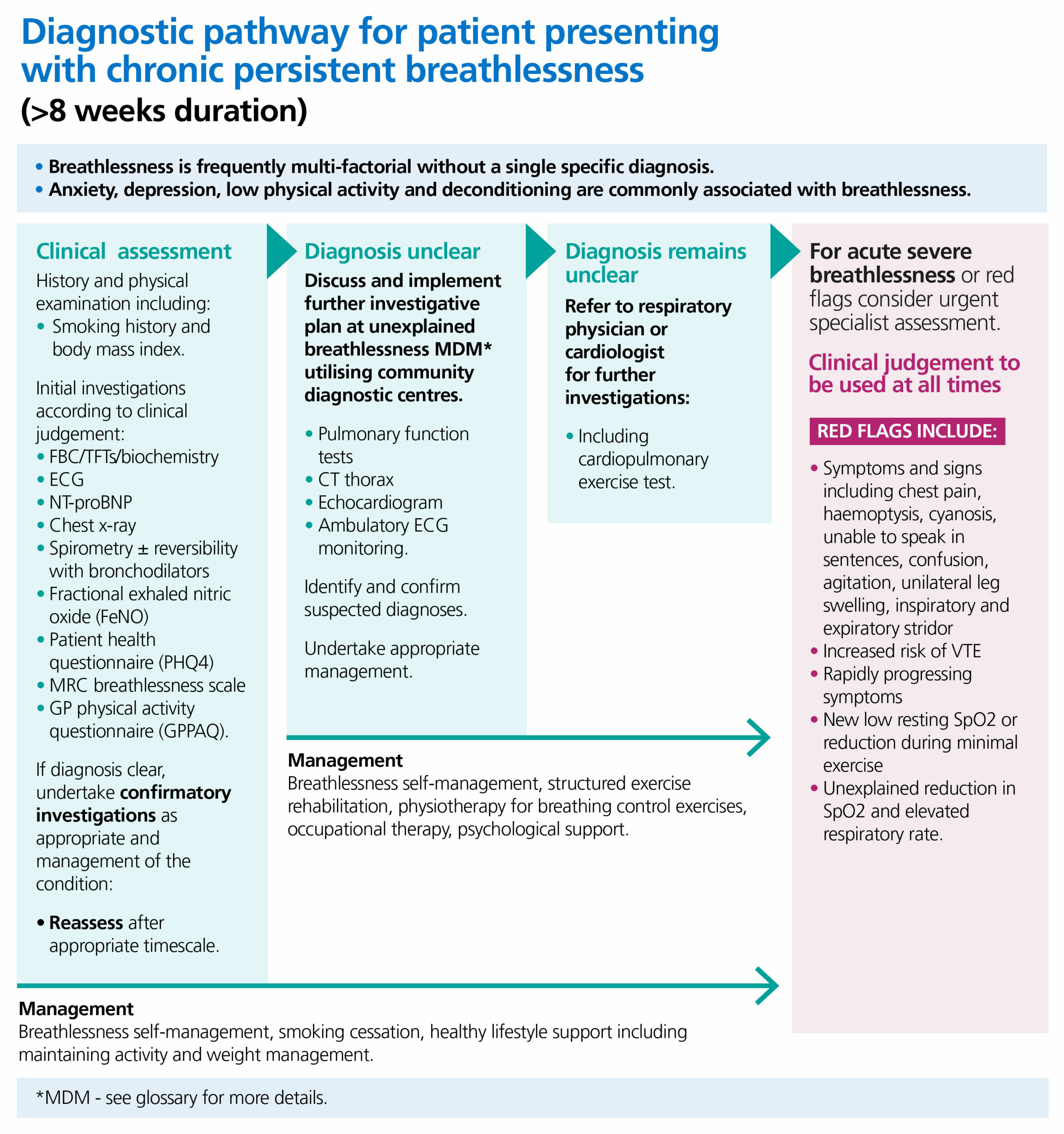

This diagram outlines the diagnostic pathway for a patient presenting with chronic persistent breathlessness with symptoms of over 8 weeks duration.

It notes that breathlessness is frequently multi-factorial without a single specific diagnosis.

Anxiety, depression, low physical activity and deconditioning are commonly associated with breathlessness.

The clinical pathway proceeds as follows;

Clinical assessment:

History and physical examination including:

- smoking history and Body Mass Index

Initial investigations according to clinical judgement:

- FBC/TFTs/biochemistry

- ECG

- NT-proBNP

- Chest X-ray

- Spirometry ± reversibility with bronchodilators

- Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ4)

- MRC Breathlessness Scale

- GP Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ)

If a diagnosis is clear, undertake confirmatory investigations as appropriate and management of the condition. Reassess the patient after appropriate timescale.

Management of symptoms may include: breathlessness self-management, smoking cessation, healthy lifestyle support including maintaining activity and weight management.

If a diagnosis is unclear:

Discuss and implement further investigative plan at unexplained breathlessness MDM utilising community diagnostic centres.

- Pulmonary Function Tests

- CT thorax

- Echocardiogram

- Ambulatory ECG monitoring

Identify and confirm suspected diagnoses.

Undertake appropriate management.

If diagnosis remains unclear:

Refer to respiratory physician or cardiologist for further investigations:

- including cardiopulmonary exercise test

Management of symptoms may include: breathlessness self-management, structured exercise rehabilitation, physiotherapy for breathing control exercises, occupational therapy, psychological support

Additional information is presented for acute severe breathlessness or red flags that may warrant urgent specialist assessment. Clinical judgement should be used at all times.

Red flags include:

- Symptoms and signs including chest pain, haemoptysis, cyanosis, unable to speak in sentences, confusion, agitation, unilateral leg swelling, inspiratory and expiratory stridor

- Increased risk of VTE

- Rapidly progressing symptoms

- New low resting SpO2 or reduction during minimal exercise

- Unexplained reduction in SpO2 and elevated respiratory rate.

Key points

General

If there is no obvious cause(s) for breathlessness after robust investigation, fitness and lifestyle factors should be addressed. Consider referral for therapeutic interventions for alcohol reduction, weight management, physical activity improvement and psychosocial support.

Referral for smoking cessation should be encouraged for all people who smoke.

Support self-management of breathlessness and utilise community resources that exist to help people learn to breathe better, e.g. swimming, yoga, pilates, or tai-chi, walks and exercise classes. Personal care plans should include these options.

Consider pulmonary or cardiac rehabilitation.

Initial presentation

The aim is to identify clear diagnosis(es), the clinical severity of the breathlessness, understand the impact on the individual and establish an appropriate management plan.

History should include onset of symptoms and associated features, including red flags; smoking history including cannabis and other smoked drugs; weight and obesity management; alcohol consumption; impact of breathlessness on daily life; levels of habitual physical exercise; environmental and occupational risk factors; co-morbid conditions; medications and recent changes in therapy; sleep quality; mental health especially anxiety; psychological distress. Consider professional carer support and informal systems around the patient i.e. relatives, neighbours or social isolation.

Basic examination should consider vital signs: BP, pulse (rate and rhythm), respiration rate, temperature, oxygen saturation; observe breathing pattern (use of accessory muscles); chest and heart auscultation; peripheral oedema and JVP; deconditioning or loss of quadriceps muscle bulk; waist circumference; calf swelling; BMI; neck circumference; PEF % predicted (for age, sex and height); expired carbon monoxide (ppm).

Primary investigations

Raised NT-proBNP requires echocardiography for confirmation of heart failure diagnosis and identification of underlying pathology by a specialist (as per NICE guidance). Breathlessness with an ECG showing AF should be considered an indication for cardiology assessment including echocardiography.

Consider a chest X-ray if not done within the last 6 months or new symptoms/signs suggesting a change in clinical picture requiring new imaging.

For diagnosis of airways disease measure the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide followed by spirometry. If the spirometry demonstrates an obstructive defect proceed to measure bronchodilator reversibility (see guidance on reinstating spirometry in England following the pandemic).

Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale

Grade |

Degree of breathlessness related to activities |

|

1 |

Not troubled by breathlessness except on strenuous exercise. |

|

2 |

Short of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill. |

|

3 |

Walks slower than most people on the level, stops after a mile or so, or stops after 15 minutes walking at own pace. |

|

4 |

Stops for breath after walking about 100 yds or after a few minutes on level ground. |

|

5 |

Too breathless to leave house, or breathless when dressing or undressing. |

Primary care coding

Description |

SNOMED |

|

Chronic breathlessness |

870535009 |

|

Serum NT-proBNP level |

414798009 |

|

Spirometry referral | 127783003 (spirometry (procedure) |

|

Echocardiogram requested |

40701008 |

|

Ambulatory ECG requested |

164850009 |

|

Patients with cardiac monitoring and record of ambulatory ECG normal |

164851008 |

|

Patients with cardiac monitoring and record of ambulatory ECG abnormal |

164852001 |

|

Suspected heart failure | 390868005 (heart failure screen procedure) |

|

Confirmed heart failure |

395105005 |

|

Referral to HF clinic |

134440006 |

|

COPD |

13645005 |

|

Asthma |

195967001 |

References

1. Hutchinson A, Pickering A, Williams P et al. Breathlessness and presentation to the emergency department: a survey and clinical record review. BMC PulmMed 2017;17(1):53.

2. Laribi S, KeijzersG, van Meer O, et al. Epidemiology of patients presenting with dyspnea to emergency departments in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region. European Journal of Emergency Medicine2019;26(5):345-9.

3. Frese T, Sobeck C, Herrmann K et al. Dyspnea the reason for encounter in general practice. J Clin Med Res 2011;3(5):239-46.

4. Stevens JP, Dechen T, SchwartzsteinR et al. Prevalence of Dyspnea Among Hospitalized Patients at the Time of Admission. Journal of pain and symptom management 2018;56(1):15-22.e2.

5. CurrowDC, Plummer JL, Crockett A et al.. A community population survey of prevalence and severity of dyspnea in adults. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38(4):533-45

6. Bowden JA, To TH, Abernethy AP et al. Predictors of chronic breathlessness: a large population study. BMC Public Health 2011;11:33.

7. Gronseth R, Vollmer WM, Hardie JA et al. Predictors of dyspnoea prevalence: results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J 2014;43(6):1610-20.

8. van MourikY, Rutten FH, Moons KG et al. Prevalence and underlying causes of dyspnoea in older people: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2014;43(3):319-26.

9. Smith AK, CurrowDC, Abernethy APetal. Prevalence and Outcomes of Breathlessness in Older Adults: A National Population Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2016;64(10):2035-41.

10. Frostad A, SoysethV, Andersen A et al. Respiratory symptoms as predictors of all-cause mortality in an urban community: a 30-year follow-up. J Intern Med 2006;259(5):520-9.

11a. Gillespie DJ, Staats BA. Unexplained dyspnea. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69(7):657-63.

11b. Viniol, A., Beidatsch, D., Frese, T. et al. Studies of the symptom dyspnoea: A systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 16, 152 (2015).

12. IMPRESS. Breathlessness IMPRESS Tips (BITs) For clinicians 2016

13. Sandberg J, Ekstrom M, BorjessonM et al. Underlying contributing conditions to breathlessness among middle-aged individuals in the general population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Respir Res 2020;7(1).

14. American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Chronic dyspnea—suspected pulmonary origin. 2012.

15. Jones. RMC et al Opportunities to diagnose COPD in routine care in the UK: a retrospective study of a clinical cohort. Lancet RespMed 2014; 2: 267

16. Fisk M et al Inaccurate diagnosis of COPD: the Welsh national COPD audit. British Journal of General Practice 2019; 69 (678):e1

17. Bottle A. et al Routes to diagnosis of heart failure: observational study using linked data in England. Heart 2018; 104(7): 600

18. SchoenheitG et al Living with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an in-depth qualitative survey of European patients Chronic Respiratory Disease 2011;8(4):225

19. Cosgrove GP et al Barriers to timely diagnosis of interstitial lung disease in the real world: the INTENSITY survey. BMC Pulmonary Medicine. 2018;18:9

Glossary

- FeNO – The fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test measures the level of NO in the exhaled breath and provides an indication of type 2 inflammation in the lungs. Alongside a detailed clinical history and other important tests to assess variability (peak flow, reversibility and challenge tests) it is used to support the diagnosis of asthma. The following link is to the Wessex Academic Health Science Network FeNO support tools free to access Using FeNO (wessexahsn.org.uk)

- NT-proBNP – Natriuretic peptides are substances released by the heart. Two main types of these substances are brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP). Normally, only small levels of BNP and NT-proBNP are found in the bloodstream.

- Unspecified Breathlessness MDM – The assessment, diagnosis and management of breathlessness is hampered by its inherent complexity and a multidisciplinary approach should be taken, with the patient utilising a one-stop-shop approach at a local community diagnostic centre where this is available.

-