Introduction

A call for evidence was open to the public for 6 weeks, from 8 April to 20 May 2025, hosted on the Citizen Space online survey platform. The survey was structured into 3 themes:

- meeting system and workforce needs

- training capacity, delivery and quality

- enabling the 3 mission shifts for the NHS

Each section explored a number of sub-themes, for instance the distribution of training posts, with a narrative overview of the evidence already emerging around that issue. Respondents could then rate their level of satisfaction with the current postgraduate medical education (PGME) system with regard to that issue and provide an optional free text explanation for their response.

At the end of the survey, respondents were invited to rank the factors influencing their satisfaction with the PGME system, the barriers to satisfaction and potential solutions or reform priorities. They could also attach or submit supporting evidence to any question in the review – this was encouraged if a respondent felt that this evidence was not reflected in the emergent findings stated under each sub-theme.

The call for evidence received 7,026 responses, including 30,950 individual free text responses.

Table 1: Number of free text responses by question

| Question | Number of free text responses |

|---|---|

| 4 | 4,062 |

| 5 | 3,506 |

| 6 | 4,189 |

| 7 | 2,719 |

| 8 | 2,771 |

| 9 | 3,326 |

| 10 | 3,041 |

| 11 | 1,583 |

| 12 | 1,719 |

| 13 | 1,359 |

| 14 | 1,601 |

| 17 | 1,074 |

Qualitative analysis – methodology

Thematic analysis coding was conducted to assign themes to free text and identify recurring patterns (for example, common views among specific respondent groups), themes and ideas across the free text responses.

The core analysis team reviewed a sample of the free text responses received in the initial 2 weeks of the call for evidence to identify emergent themes and develop a coding framework. The team also cross-referenced the manually identified themes with suggestions generated by Microsoft Co-Pilot to finalise the framework.

A team of 20 colleagues conducted the thematic coding, meeting weekly to feed back on the relevance and viability of the coding framework, discuss emergent findings, manage distribution, discuss whether saturation had been reached for any questions and ensure that stakeholder groups were appropriately represented across the coded sample.

When coding saturation had been reached (that is, clear patterns had emerged with no significant new insights emerging beyond a small number of outliers), coding for that question was stopped. The Review team ensured that all organisational responses were read and coded.

Table 2: Number and proportion of coded free text responses by question

| Question | Free text entries | Coded | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4,062 | 2,263 | 56% |

| 5 | 3,506 | 2,842 | 81% |

| 6 | 4,189 | 1,279 | 31% |

| 7 | 2,719 | 913 | 34% |

| 8 | 2,771 | 989 | 36% |

| 9 | 3,326 | 884 | 27% |

| 10 | 3,041 | 871 | 29% |

| 11 | 1,583 | 565 | 36% |

| 12 | 1,719 | 592 | 34% |

| 13 | 1,359 | 659 | 48% |

| 14 | 1,601 | 648 | 40% |

| 17 | 1,074 | 385 | 36% |

| Total | 30,950 | 12,890 | 42% |

Coded questions were analysed to ensure that all stakeholder views were represented and that less well represented stakeholder groups were included in the coded sample.

Classification of respondents’ profession or stakeholder group

Respondents could select multiple boxes to denote their profession or stakeholder group; for example, those who selected medical student may have also selected foundation, core or higher specialty trainee. We treated them as responding from multiple perspectives, having completed all those stages of training, and based our analysis on the most senior stage of training selected. Where respondents indicated that they are both a consultant and a trainer/faculty member, we classified them as the latter.

Table 3: Number of respondents by type

| Profession (group) | Profession/role | Count |

|---|---|---|

| Doctors on Specialist Register | Doctor – military Doctor – on the Specialist Register or GP Register | 586 |

| Educator | Medical education manager Senior training faculty (director of medical education, associate or deputy dean, postgraduate dean) Trainer/educator (training programme director, college tutor, head of school, educational or clinical supervisor or clinical trainer) | 710 |

| Locally employed doctor | Doctor – locally employed doctor Locum doctor | 842 |

| Medical student | Medical degree student Medical degree student – applicant | 1,778 |

| Other | Academic/clinical fellow Academic researcher Charity representative Employer/service manager Library services Medical manager Medical Royal College representative Other – not stated Other clinical professional Other clinical student Other NHS clerical role Patient Policy-maker Prefer not to say Relative of a doctor Retired doctor Trade union representative Unemployed/working abroad Unemployed doctor/working abroad | 195 |

| Resident doctors | Doctor in postgraduate training (core) Doctor in postgraduate training (foundation) Doctor in postgraduate training (higher specialty/run-through/GP specialty trainee) | 2,628 |

| SAS | Doctor – specialty/specialist grade | 287 |

| Total | 7,026 |

Theme 1: Is postgraduate medical training meeting the needs and expectations of patients, healthcare services and doctors?

Q4: Recruitment to and distribution of training posts meets the health needs of patients and the population

7,007 respondents answered this question, with 76.7% (n=5,376) either disagreeing (n=2,267) or strongly disagreeing (n=3,109) that the current system of recruitment and distribution meets the health needs of patients and the population.

Qualitative analysis of the free text responses showed that the availability of training posts was the predominant concern across the majority of stakeholder groups, with 35% of coded responses (784 of 2,263) calling for an increase in the number of posts. This was considered to be a priority for both meeting system or workforce needs and enhancing training delivery, capacity and quality.

Respondents felt that there were insufficient training posts to meet current and future patient and population need. Some respondents pointed to locum usage and the increase in locally employed doctors (LEDs) as an indicator of a deficiency of training posts. From a training perspective, respondents reasoned that more posts were required to reduce service pressures and therefore improve training quality by freeing up time to undertake educationally relevant activity.

Competition for specialty training positions was highlighted as a key issue, with the growing number of applicants outstripping the number of available training posts, thereby creating bottlenecks and hindering career progression. Indeed, the significant number of LEDs responding to the call for evidence (12% of all respondents) could also be an indicator of the scale of this issue. In addition to calling for an increase in the number of training posts, a smaller number of respondents advocated for prioritising UK medical graduates to resolve the current training bottleneck.

There is currently a bottleneck of training posts that is preventing extremely enthusiastic and competent doctors across all specialty interests from entering training. This is leading to doctors being stuck in ‘service provision’ trust grade roles, unable to make use of their expertise or adequately develop their skills.

This creates problems as without an adequate number of registrars, trainees cannot attend clinics and help with the mounting backlog of elective or non-urgent secondary care. This is directly preventing patients from accessing care in a timely manner and bottlenecks only lead to more burnout among trainees and encourage people to move abroad or seek alternative careers.

Resident doctor (higher specialty/run-through/GP specialty trainee)

The number of consultant posts was also a prominent theme, with respondents pointing to current consultant vacancy rates and the potential for a bottleneck higher up the medical workforce supply pipeline should training numbers increase.

We also heard that training posts are inequitably distributed, with a number of respondents calling for better alignment with population need and service demand. Some suggested that centralised national recruitment and rotational training deepened health inequalities, as resident doctors move to areas where they have fewer ties to the community and rotate out before they develop an understanding of the local population. Others advocated for incentivising areas of low recruitment, either with pay premia or training benefits such as funded qualifications or enhanced mentorship and supervision.

The RCP has long argued that there is a fundamental mismatch between the distribution of training posts and local population health needs. The expansion of training posts has not kept pace with a changing demographic, especially in specialties with growing patient demand and where the introduction of new therapies requires a high level of clinical expertise. Alongside the promised expansion of medical school places, the NHS must fund and deliver a major expansion in postgraduate training posts for the medical specialties. In particular, areas with higher health inequalities and/or a high proportion of older people living with frailty or chronic conditions should be funded for more training posts.

Royal College of Physicians

A smaller number of responses wanted to reform the current recruitment system by limiting the number of specialties to which an individual applicant can apply. Others queried whether the multi-specialty recruitment assessment (MSRA) was an appropriate, effective and fair selection system for all medical specialties.

Finally, the current rotational structure of training arose as a significant issue. Respondents highlighted the impact of frequent rotations on their quality of life, due to the social and financial stress of relocation, separation from personal support networks and feelings of isolation in the workplace. We heard that resident doctors’ lack of autonomy over the location of training – associated with both rotational training and centralised national recruitment – was affecting morale. Similarly, respondents reported feelings of being undervalued or excluded as non-permanent staff members. Residents reported issues with wellbeing support, having a lack of agency and experiencing a lack of engagement from employers, resulting in feelings of exclusion and “infantilisation”.

Others made the case that frequent rotations reduced training quality as it was difficult to build relationships with trainers and departments during the allotted placement duration. With limited time for residents to familiarise themselves with workplace systems and local populations, it was also argued that this reduced placements’ educational benefits. Finally, we heard that rotational training potentially impacted on service provision. These respondents made the case that frequent rotations reduce continuity of care and that low morale associated with rotations can also impact on quality of care.

Such frequent rotation does not allow enough time for doctors to settle into any one post or develop lasting working relationships with colleagues and seniors. This means they are less likely to be trusted with direct care of the patient, and negatively impacts the learning curve, such that by the time trainees reach CCT, they still have not had the experience/degree of independence their predecessors had, and are therefore less capable in their care of patients.

Resident doctor (higher specialty/run-through/GP specialty trainee)

Q5: The current distribution of training posts meets the needs of healthcare service providers in delivering healthcare and developing their future medical workforce

6,984 respondents answered this question, with 82.2% (n=5,744) either disagreeing (n=2,066) or strongly disagreeing (n=3,678) that the current distribution of training posts meets the needs of healthcare service providers in delivering healthcare and developing their future medical workforce.

Free text analysis identified similar themes to question 4, with the number of available training posts again being the predominant theme. 38% of responses advocated for increasing the number of training posts (1,343 of 3,506 coded responses). 15% of coded responses also cited a misalignment of training post distribution with population health needs – with cities and tertiary centres seen to be favoured over remote and rural locations and district general hospitals. The General Medical Council (GMC) suggested that a shift towards more community placements could help to address this issue. Some responses also called for an increase in training posts to redress the imbalance.

Training posts are not currently aligned with patient demand – so their distribution does not meet the needs of healthcare service providers. Some underserved areas – especially rural, coastal and economically deprived regions – struggle to fill and retain training posts despite a clear service need and patient demand (for example, areas with an older population living with frailty or multiple chronic conditions). Regional hub-and-spoke improvement networks should be developed to share best practice and lessons learned.

Royal College of Physicians

A number of respondents referred to understaffing and rota gaps as a consequence of an insufficient number and maldistribution of training posts. This was also associated with reduced access to training opportunities, further compounded by growing service pressures taking residents away from educationally relevant activity.

Training bottlenecks arose again as an issue impacting on morale, retention and consequently quality of care. Similarly, frequent rotations were cited as impacting on morale and training quality.

12% of coded responses discussed recruitment processes and put forward a range of ideas for reform, including devolving recruitment; weighting allocation towards applicants’ location (for example, close to their medical school or familial networks); taking specialty preference into account when applicants apply to multiple specialties; and improving communications throughout the stage of the recruitment process. The random allocation system for the foundation programme was a commonly raised issue, with some respondents calling for a return to a ranking system based on academic attainment.

It was argued that these reforms would improve morale; help systems to “grow their own” workforce, rooted in the local population and cognisant of their health needs; and produce a workforce that was more committed to their vocation, resulting in better quality of care.

Q6: The current model of postgraduate medical training meets the personal and professional needs of most doctors

6,982 respondents answered this question, with 79.7% (n=5,568) either disagreeing (n=1,943) or strongly disagreeing (n=3,625) that the current model of postgraduate medical training meets the personal and professional needs of most doctors.

Free text responses largely related to training experience and support for residents, and career satisfaction. The learning environment and preparedness for practice were also discussed, although less frequently.

As with previous questions, respondents reported that the current rotational training system impacts on residents’ quality of life and ability to settle and put down roots, and that service demands reduce access to training. Work–life balance was also a reported issue, often associated with the perceived volume of doctors’ administrative workload. Similarly, this issue was raised in relation to the burden of resident doctors’ portfolio requirements and the educational relevance and value of the activity undertaken in placement.

While many junior doctors report good teaching, high levels of burnout suggest the training model is not meeting the needs of many. Contributing factors include exhausting rotas, unsafe staffing, financial strain and frequent relocations. Over a quarter say rota gaps harm training, and hidden costs like exams or courses exacerbate pressure – especially for those from less affluent or international backgrounds.

East of England Enhance programme

Respondents referred to the “hamster wheel” of PGME, associated with the rigidity of training structures and increased competition for training places. We heard that training bottlenecks create higher portfolio requirements and thresholds for applicants to obtain an interview, at the same time as service demands are reducing access to portfolio-enhancing activities. A number of respondents called for an increase in training posts to address these issues.

More and more of our [doctors in training] want to do training but not on the standard ‘hamster wheel’ of training. They want to train ‘outside the box’ and, yes, we have the fellowship pathway, but it is very patchy what trusts then offer to them in terms of training when they come in as SAS/LEDs.

Medical education manager

Frequent rotations were again associated with reduced training quality, due to residents having insufficient time to build productive relationships and get into the “learning zone”. A small number of respondents felt that wider workforce deployment compounded this issue, with other professions accessing training opportunities that would otherwise be afforded to resident doctors and benefitting from more long-standing relationships with senior doctors that are unobtainable for rotating residents.

Some respondents called for more meaningful support and mentorship to address this issue, including the reinstatement of “the firm” model of training – apprenticeship style training within a medical team headed up by the consultant, enabled by fewer rotations.

Q7: Current training processes are flexible enough to meet the needs of most doctors

6,993 of respondents answered this question, with 54.3% (n=3,797) either disagreeing (n=1,759) or strongly disagreeing (n=2,038) that current training processes are flexible enough to meet the needs of most doctors.

Free text responses largely focused on training experience and support for resident doctors; career satisfaction and support for progression and personal development; workforce distribution and planning; and, to a lesser extent, the learning environment.

Resident doctors of all grades made the case that the frequent rotations associated with the current training model are inherently inflexible, reducing personal choice and agency and failing to accommodate personal circumstances. The comments also highlighted the perceived impersonal nature of rotational training. It was argued that greater flexibility over placements would support wellbeing and improve motivation and performance. Practical issues related to rotas and annual leave arising from movement between employers were also frequently cited.

Flexibility in hospital placement is not simply a personal convenience – it enhances retention, supports wellbeing and allows doctors to train in environments aligned with their future goals.

Higher/run-through/GP specialty trainee

While there was widespread positivity about the flexible training initiatives that are currently on offer, such as less than full-time (LTFT) training, respondents highlighted cultural issues of stigma, judgement and negative attitudes towards those resident doctors who take up these offers.

We also heard that training structures are considered to be too rigid, with fixed rotational placement start dates (for example, August) and difficulties switching programme or stepping out and back into training. Others pointed to the “tick box” nature of curricula delivery, work-based assessments and the Annual Review of Competency Progression (ARCP) as being rigid and inflexible.

Within formal training, there are issues in limiting the opportunities to gain learning in different ways, with limitations on moving out of programme (although these have improved in recent years, they are still not the norm). Moreover, in spite of attempts in the last curricula review, there is still very limited scope for applying learning from one specialty to another. We also believe that postgraduate curricula could be deployed more flexibly to support doctors’ learning wherever that takes place.

General Medical Council

We heard from some respondents that access to flexible training initiatives can vary due to inconsistencies in the approach to considering and approving applications across regions, specialties and employers. Similarly, some issues were highlighted with the management and delivery of flexible schemes. Some respondents felt that, in some instances, systems were complicated and poorly understood by the faculty staff who administer them. The financial impact of LTFT training and likelihood of requiring a training extension were also highlighted as barriers to uptake.

While improvements have been made to previously entirely inflexible systems, which are welcome, resident doctors still express dissatisfaction with the options available to them. One of the trade-offs that causes dissatisfaction is that access to any flexible options extends the time needed to complete the training pathway, associated level of remuneration remains lower for longer and they are often perceived as ‘second rate’ compared to those who complete training full time.

Despite flexibility being recognised as essential to the modern medical workforce in postgraduate training reviews over the past 3 decades, these options continue to lack substance and incentives to make them meaningful routes of progression and completion for many.

Academic researcher

A smaller number of respondents focused on the availability of alternative or less conventional training pathways and advocated for greater support for those doctors who wish to pursue a portfolio career rather than progress though the established training pathway without taking a break. Some called for greater recognition of competencies acquired outside formal training.

There was also a minority view that flexible training initiatives can negatively impact on training programme planning, service provision and the quality of training. We heard that faculties sometimes lack the capacity to manage these initiatives well.

Theme 2: Training capacity, delivery and quality

Q8: The current postgraduate medical training adequately prepares doctors for the professional and clinical demands of their future roles

6,979 of respondents answered this question, with 46.68% (n=3,258) either disagreeing (n=1,953) or strongly disagreeing (n=1,305) that the current system of postgraduate medical training adequately prepares doctors for the professional and clinical demands of their future roles.

The majority of coded free text responses related to quality of training and education provision. A smaller proportion of respondents also discussed training experience and support for resident doctors, and how well the postgraduate medical training system equips doctors with the necessary skills for their future roles as senior medical decision-makers.

The most common theme was the quality and relevance of training. When considering the competencies that were underdeveloped in the current training system, respondents pointed to the non-clinical, holistic skills required to successfully fulfil the professional duties of a consultant or GP. These included leadership and management, task prioritisation and time management, sustainability and resource management, dealing with legal issues and patient communication.

Clinical decision-making, procedural skills and incident investigation arose as clinical skills requiring greater development. Some respondents referred to additional support required post certificate of completion of training (CCT) and to fellowships taken outside training to prepare doctors for the consultant role as evidence that the current system of PGME is not meeting the profession’s needs.

The current PG pathway does not consistently equip doctors with the practical, leadership, adaptability and community-facing skills needed in today’s NHS. Many newly appointed consultants, GPs, SAS and locally employed doctors report being underprepared for the broader professional and systemic demands of their roles.

Senior training faculty member

In the context of increasing patient complexity, changing demographics, patient expectations and rapid technological development, some respondents queried whether curricula and training programmes were able to keep up with the rate of change and remain relevant to future practice.

The European Working Time Directive remains a point of contention, with residents reporting that they had to take on additional out of hours’ work to get the necessary exposure for their curriculum progression. We heard from some respondents that the current PGME system does not build the resilience or professional autonomy required of a senior medical practitioner and that residents’ expectations are not always met by the reality of the role.

While clinical competence is generally well-supported, there are several critical gaps in preparedness – particularly in procedural, supervisory, leadership and non-clinical domains. Many trainees find it necessary to take out of programme experiences to gain skills or experiences not available within standard training. This includes advanced procedural skills, leadership development, research and education roles. The need to pursue development externally reflects structural gaps in the training programme itself.

Association for the Study of Medical Education (ASME)

Residents wanted more clinic time, 1-to-1 bedside teaching and opportunities to take responsibility for clinical care and decision-making. While some respondents valued rotations and high intensity of work for providing exposure to a variety of conditions, it was argued that better senior support was required for these encounters to be educationally valuable.

Service pressures arose once more as the main barrier to quality education and training, with one respondent describing placements as “largely service provision and a hope of learning by osmosis”. Again, respondents pointed to administrative burdens and rota coverage hindering opportunities to acquire procedural, diagnostic and clinical decision-making skills. Service demands were also associated with fragmented time with supervisors, with consultant workload also reducing teaching opportunities. Respondents pointed to a lack of role modelling from senior doctors, with some again calling for longer placements and a return to “the firm” apprenticeship model.

Lack of role models. The newer doctors are often working alone, with limited back up – hence they don’t get to see how the job is meant to be done. The firm structure of old helped by having someone above you to watch and learn from; that rarely happens now as too busy, too short staffed. Many of the problems for doctors in training is they haven’t been taught how to prioritise job lists, working efficiently in clinic, as no-one is free to teach them.

Senior faculty member

Feedback also referred to variable training quality across specialties, geographies, employers and departments – with cultures and attitudes towards education often being specific to the placements and teams that residents are placed within. Some respondents highlighted variation in ARCP outcomes between regions as evidence of this.

There was a feeling among some respondents, particularly medical students and resident doctors, that members of the wider clinical team, such as physician associates and advanced clinical practitioners, were taking development opportunities away from postgraduate medical trainees and increasing their workload. Others called for these associate roles to be better used to alleviate the administrative or ward-based workload on resident doctors, releasing residents to attend clinics and procedural training opportunities. A smaller number felt they were unprepared to manage and deploy the skills of the multiprofessional team, and that greater emphasis on this would be required if this is the direction of travel for service delivery.

A small number of respondents made suggestions regarding the structure of training – such as shortening training duration, including shortening foundation training, with a focus on acuity and generalist skills, before earlier entry into specialty training. The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) recommended introducing a defined “senior registrar” ST7 role focused on developing independence, clinical judgement and leadership skills, to prepare senior residents for future consultant roles.

Q9: The current system of postgraduate medical education provides doctors with a high quality learning environment

6,969 of respondents answered this question, with 58.8% (n=4,101) either disagreeing (n=2,210) or strongly disagreeing (n=1,891) that the current system of PGME provides doctors with a high quality learning environment.

Service demands and the prioritisation of service provision over training emerged as the most commonly raised barrier across all stakeholder groups to the quality of the learning environment, with the majority (55%) of coded free text responses highlighting this issue. Understaffing was highlighted by some respondents as a contributory factor to this. The British Medical Association (BMA) also linked service pressures and overwork to a deterioration of behaviour in the working environment. In a 2018 survey of 7,000 doctors by the BMA, two-thirds reported bullying and harassment as a problem in their main place of work.

It depends on what you view as a high quality learning environment. My view is that there is learning to be gained from every patient interaction for a proactive doctor in training. Sometimes the balance is wrong here when we are overwhelmed with clinical work. The capacity to be able to learn and teach is outweighed by the need to provide clinical care.

Medical educator

Questioning the educational relevance of tasks undertaken in placement, residents wanted to see a higher volume and greater variety of presentations, better access to high-quality simulation and more regular, timetabled teaching. Some queried the relevance of centrally developed curricula and of time-consuming curricular requirements such as audits, particularly in the context of 6-month placements.

The most common view was that clinical teaching at the patient’s bedside offered the greatest educational value. However, fragmented formal 1-to-1 interaction between residents and supervisors was emphasised as a barrier to this.

What is actually useful is bedside teaching and consultants don’t get the time to do this because we are in a rush with so many patients to get through in the day.

Foundation doctor

We heard again that the quality of the learning environment varied between placements, with some respondents calling for standardisation to ensure that employers meet minimum educational infrastructure standards; for example, teaching time, resources and appropriate supervision.

A smaller number of respondents felt that frequent rotations between placements curtailed the educational benefits of the learning environment, with one commenting “varying hospital settings have their own learning experience, but long-term [benefits] can only be gained when [residents] have prolonged contact or time to become part of a team”.

Some called for an increase in education and training resourcing; for greater assurance that education funding was being used as intended by employers; and for more protected time for training in supervisor’s job plans.

Q10: Trainers in postgraduate medical education have sufficient time, support and resources to deliver quality supervision and training

6,972 of respondents answered this question, with 68.9% (n=4,809) either disagreeing (n=2,454) or strongly disagreeing (n=2,355) that trainers have sufficient time, support and resources to deliver quality supervision and training.

Respondents mainly regarded this as a training quality and delivery issue; however, 24% of coded responses also linked the matter to meeting system and workforce needs.

The most commonly raised issues were a lack of protected time for educator duties (55% of all coded responses) and insufficient educator capacity (52% of all coded responses). Respondents reported that the supporting professional activities in consultant job plans did not reflect the true time commitment required to supervise. We heard that the PGME system relied on the goodwill of consultants, who spent their own time outside working hours fitting in training.

One of the most significant challenges is the lack of genuinely protected time in trainers’ job plans. Many are expected to deliver supervision and education alongside full clinical workloads, leading to compromised teaching quality and trainee support. Clear allocation of dedicated educational time, enforced and monitored by trusts, is essential.

Locally employed doctor

Those respondents who discussed educator capacity highlighted competing clinical priorities and pressures to increase service productivity and patient flow in the context of the NHS backlog. We also heard that the ratio of trainees to trainers was increasing to the detriment of high quality supervision and that this was compounded by expansion plans in some specialties. The Royal College of General Practitioners reported that 47% of general practice staff cited a shortage of educators or supervisors as a barrier to taking on GP registrars or other learners. Some of those respondents from primary care backgrounds also commented on estates and facilities as a barrier to educators’ ability to deliver high quality training and supervision.

It is neither fair nor sustainable to expect trainers to juggle these competing demands without proper support. Supervision should be a structured, respected and protected part of a consultant’s role, not an afterthought squeezed between clinics and on-calls. The system currently asks the impossible and then feigns surprise when the educational experience falls short.

Foundation doctor

Constant expansion of training places, constant emails from deaneries asking for more and more training places. To supervise trainees we have to sacrifice consultation time for our regular patients. Resources are insufficient for this. Many trainers complain that they don’t get sufficient trainer prep time/protected time, even though this is enshrined in the trainer standards. I’m fortunate that I do get such protected time, but I am a partner and can demand it. Many salaried GPs feel disempowered.

GP trainer

Understaffing and a wider culture of deprioritising training were regarded as the main causal factors for the issues highlighted above. We also heard that unclear incentives or progression routes for trainers play a part in the current shortage of trainers and lack of education capacity. Potential solutions included better trainer pay, funding for relevant qualifications, more formal recognition (for example, clinical excellence awards) and formal routes into trainer roles.

Most senior clinicians provide their expertise and time for free. Most employing healthcare providers struggle to understand and support educators in the workplace at the expense of thinking that clinical training is reducing healthcare delivery capacity. A radical mindset change is required by NHS employers.

Medical trainer/educator

Q11: Postgraduate medical training creates an equitable and inclusive environment for doctors from diverse backgrounds, including those from minority ethnic groups and those with disabilities

Responses to this question were more evenly spread. Of the 6,976 answers, 35% (n=2,035) either agreed (n=1,814) or strongly agreed (n=627) with the statement. However, 35.8% of respondents neither agreed or disagreed (n=1,668) or didn’t know (n=832).

Fewer respondents provided written feedback than for previous questions and, of the responses that were coded, there was a higher degree of positivity regarding inclusivity within PGME. These respondents acknowledged progress in this area, provided examples of good practice and felt that an appropriate level of attention, resource and support was given to equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) initiatives.

A lot of work has been done to create an equitable and inclusive training environment and evidence is demonstrating a positive impact, but we must not become complacent. Protected characteristics no longer predict success at national selection and we must continue to work to ensure progress through training and successful outcome at CCT also remains independent of protected characteristics.

Doctor – on the Specialist Register or GP Register

The most commonly raised issues related to implementation of and accountability for EDI. Such responses called for more robust EDI requirements and better metrics and monitoring, with consequences for discriminatory behaviours. They also advocated for better defined and protected routes for raising concerns.

To address differential attainment, sexism and microaggressions, significant change is required. First and foremost, there must be clear, effective channels for raising concerns, with a robust escalation process in place to ensure that complaints are taken seriously. This should include regular training for senior staff on diversity and inclusion, with a zero-tolerance policy for discrimination.

Medical degree student

We heard about systemic biases creating barriers and resulting in differential attainment for doctors with protected characteristics. These ranged from societal, institutional and unconscious biases, to microaggressions and indirect discrimination and to more overt racism, sexism and ableism in the workplace. To a lesser extent, we heard that doctors from lower socioeconomic backgrounds experienced barriers to progression. These were financial but also social and cultural, as these doctors did not benefit from the social networks, experiences and opportunities enjoyed by their better connected peers.

Some specific PGME processes – such as recruitment, examinations and assessment –were also perceived as creating inequalities. Respondents called for more diverse assessment panels and queried whether situational judgement tests – such as the MSRA – were exclusionary.

Rotational training was specifically highlighted by a smaller number of respondents as exacerbating inequalities, particularly for those with disabilities for whom long-distance commutes can present a challenge and workplace adjustments are a necessity. There was also the view that frequent rotations reduced the likelihood of an employer investigating and resolving issues of discrimination, bullying and harassment, as residents move on to their next placement before such matters can be resolved.

Rotational training is not easy for doctors with disabilities, especially when the region is large and commutes are long. The need to cover the rota with so few doctors means adjusted working pattern requests cause conflict. I do not get disability adjustments to help me access regional training days despite asking because there is no time or funding to provide these.

Resident doctor

Discrimination and inequality were generally regarded as being endemic across the NHS, rather than being a PGME-specific issue, and respondents called for top-down systemic culture change, led by the august bodies, senior members of the medical profession and the NHS leadership. There were also suggestions for improving educators’ understanding of EDI, to drive a more inclusive learning environment.

There should be integrated, multiprofessional teaching and workshop sessions as poor behaviours and less than ideal cultures are the responsibility of all within clinical and learning environments. The data on differential attainment, on sexual safety, on discrimination and lack of parity is all too clear – there needs to be significant action and trusts need to be able to hold doctors, and all staff, accountable. Too often I have heard resident doctors and other healthcare professionals refer to some senior colleagues as ‘untouchable’.

Senior PGME faculty member

A number of responses highlighted the particular discrimination and barriers to progression experienced by international medical graduates (IMGs), as evidenced by differential attainment and over-representation in service grades among this group. It was suggested that IMGs might not have the awareness or confidence to escalate issues of discrimination. Calls for the prioritisation of UK graduates for postgraduate training posts had deepened feelings of disparity and subordination.

Others called for additional support for IMGs, including induction to facilitate their integration, understanding of systems and cultural norms within the NHS, and structured support to tackle differential attainment.

Recognise IMG status as an independent risk factor for exclusion and structural disadvantage. Track and publish training outcomes, ARCP results, exam pass rates and referral data by IMG status, not just ethnicity. Introduce national standards for IMG induction, supervision and mentorship, with deanery-level enforcement. Ensure complaints processes include oversight that reflects visa status and power imbalances. Create structured progression routes out of service roles for IMG doctors, with real access to training.

IMG Voice

Theme 3: Enabling and reforming PGME to achieve the 3 NHS mission shifts

Q12: Postgraduate medical training should include more opportunities in community-based settings to better align with patient and community needs

Of the 6,989 responses to this question, 46.4% (n=3,243) either agreed (n=2,085) or strongly agreed (n=1,161) that training should include more opportunities in community-based settings. However, 34% (n=2,384) of respondents neither agreed or disagreed with the statement or selected “don’t know”.

The most commonly expressed view was that the relevance and suitability of community placements would be dependent on the medical specialty; for example, ‘craft specialties’ such as surgery provide specialist care and require specialist space, staff and equipment that are only available in hospital/tertiary settings. It was felt that a move to community placements would neither be appropriate nor good use of resources for these specialties. However, some respondents who expressed this view agreed that training content could place a greater emphasis on the patient pathway between secondary and community care including, for example, perioperative medicine for surgical specialty trainees.

Surgery is a hospital-based discipline. Surgery by nature will not be transferable to a community setting. The use of surgical specialists’ time is best spent delivering surgical care and procedures in hospital settings. However, there is much we can do to prepare our trainees to engage with community care.

The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland

There have been attempts previously, with the creation of the office urologists, to move surgeons into the community and to do less operating. This was not a successful pilot, and it would appear unlikely that this sort of professional opportunity would have a large uptake. Surgeons would perhaps be better trained to look after the community by having more exposure to perioperative medicine and intensive care.

Joint Committee on Surgical Training (JCST)

There was a degree of support for a greater emphasis on population health and prevention, with a recognition that community placements provide valuable skills in managing long-term conditions; understanding health inequalities and the social determinants of health; and improving patient communication. Some also stressed the importance of doctors in acute/hospital-based specialties having exposure to community care to improve their understanding of the full patient journey and challenges in the community setting.

Working in general practice has made me realise I had no idea what goes on in the community. Work with our relevant allied health professionals – health visitors, community midwives, community physios and OTs. Hospital specialities spending time in general practice so they can see the other side rather than sending tasks for us to do that are really easy in the hospital to sort, but a nightmare in the community. If we knew what was going on in the community, I feel the NHS would run more efficiently as we’d have more realistic expectations of our colleagues

Resident doctor (higher specialty/run-through/GP specialty trainee)

Some respondents stressed the need to strike the correct balance between community and acute settings, and for doctors’ personal preferences to be considered; for example, providing opportunities for those wanting to take a special interest in community-based medicine. Others felt that community exposure was most beneficial in the early years of training, to provide a grounding and appreciation prior to specialisation. It was noted that the current Foundation Programme already offers a GP placement to 45–50% of second year foundation doctors, with plans to increase that number further.

We also heard concerns regarding insufficient resources (for example, staff, facilities, estates) in the community to support training expansion in this setting. Some argued that further education infrastructural investment was first required to enable this. Highlighting current education capacity challenges in general practice – with a further GP expansion in the pipeline – some cautioned that any plans to deliver more training in the community would need to be carefully considered and resourced, with greater use of technology and innovation to build capacity; for example, through blended learning.

Others made the case that integration between acute, community, primary and social care would first need to be better realised at service level, before training could follow.

This is predominantly a service configuration, not training question. If the service configuration is towards offsite assessment/diagnostic centres served by specialists, we will train doctors in/to work from these environments. For specific sub-specialities (for example, heart failure) there is a role for community-based specialists, but the current curriculum does not allow us the bandwidth to develop this.

Cardiology Specialty Advisory Committee

Q13: Postgraduate medical training curricula should include a stronger focus on addressing health inequalities, social determinants of health and population health

6,986 respondents answered this question, with 59% (n=4,118) either agreeing (n=2,438) or strongly agreeing (n=1,680) that curricula should include a stronger focus on addressing health inequalities, social determinants of health and population health. To note, 26% (n=1,804) responding to the question neither agreed nor disagreed with the statement or selected “don’t know”.

Among those querying the statement, the most commonly expressed view was that government and policy-makers were better placed to drive the systemic changes required to improve public and population health than individual clinicians, who lack the same leverage to effect change. Among these responses, a number stated that public health investment would have a greater impact than adding content to postgraduate medical curricula.

We also heard that service redesign was first required to allow this shift in the focus of training. There was concern among some respondents that postgraduate curricula were already overcrowded and any new content or requirements regarding population health could be detrimental to clinical skill development.

While I agreed the curricula should include this, the onus is rather on the government, not doctors, to address the social determinants of health. As doctors, we can very easily recognise how poor housing contributes to a multitude of healthcare conditions. However, we cannot directly change our patients’ social circumstances, as much as we might like to be able to. This is the job of government.

Resident doctor (higher specialty/run through/GP specialty training)

It was again argued that population health was more relevant to some medical specialties, such as general practice and public health, than others. A small proportion of respondents suggested that other clinical professions and members of the multidisciplinary team were better suited to take on population health management, with doctors focusing on clinical diagnosis, management and treatment.

Others acknowledged the importance of population health across medicine but asserted that there was sufficient focus in the postgraduate curricula already, with the GMC’s generic professional capabilities framework cited as the main driver for this. We also heard that this content was prominent in undergraduate curricula. The key for many was striking the right balance and ensuring that content was relevant and tailored to the specialty.

Q14: Postgraduate medical training should incorporate more content on digital health, artificial intelligence (AI) and remote care, including the use of technologies such as extended reality, AI and machine learning, to enhance learning experiences and improve training capacity

6,992 respondents answered this question, with 58.4% (n=4,081) either agreeing (n=2,324) or strongly agreeing (n=1,757) that PGME should incorporate more content on digital health, AI and remote care. There was also a degree of ambivalence, with 24% (n=1,687) of respondents neither agreeing nor disagreeing with the proposition or selecting “don’t know”.

The most commonly expressed opinion in the free text responses was that the NHS should “get the digital basics right first” – that is, the existing technology and digital infrastructure required for modernisation or bringing up to a minimum standard before pursuing more ambitious aims with new and novel technologies. These responses referred to difficulties conducting daily tasks with current IT facilities and expressed scepticism towards the proposition of the question.

NHS workers are hampered in their actions every day by slow, out-of-date networks and computers and by insufficient numbers of computers. These basic needs must be addressed before the introduction of other new technologies, including artificial intelligence.

Doctor – on the specialist register or GP register

Similarly, others spoke of the system, infrastructure and cultural challenges of incorporating novel technology into PGME and into healthcare more generally, arguing that significant investment was needed to achieve the vision alongside effective change management to “bring people on the journey”. Some responses expressed a degree of scepticism, given the failure of previous high profile NHS digital initiatives. There were also concerns that any such initiatives would be tokenistic.

This is obviously a rapidly expanding field, one that is quite clearly going to revolutionise many areas of healthcare practice. Many trainees are considerably better educated in this field than their consultant trainers. As with simulation training, this will only be as useful or effective as the resources put behind it. Proper investment is required to make the most of this growing industry in a healthcare education setting.

Specialist Advisory Committee for ENT

Other free text responses were sceptical over the relevance of AI in particular at its current stage of development, expressing a concern that the introduction of such novel technologies could undermine the fundamentals of quality, person-centred, knowledge-based, evidence-led care. These respondents emphasised that clinical and professional competence should be the priority.

This is probably the way to go but there are very few validated, safe AI tools available at present. They will never replace experience and the art of medicine especially as a computer cannot physically examine a patient.

Medical trainer/educator

We also heard that PGME should prioritise personal interaction and face-to-face training, particularly for those patients who experience or are at risk of digital exclusion. Some respondents who expressed this view called for AI and machine learning to free up capacity to engage with patients; for example, by relieving clinicians of basic administrative tasks.

When this is incorporated consistently across the nation this should be included, but as this is not routine it feels inequitable to incorporate more content on this at present. Learning how to manage patients remotely in preparation for future health crises, such as a pandemic, would be helpful to incorporate.

Doctor – on the specialist register or GP register

There were those who advocated for more training content on AI, simulation and digital tools given the direction of travel. Medical Royal Colleges, in particular, called for training to keep pace with technological transformation and for structured opportunities for doctors to train as digital leaders. Given the speed of innovation, it was recognised that more evidence was needed regarding the risks and benefits of machine learning and AI, to inform guidelines on their appropriate use, to define safe, ethical practice and to determine what training should look like. Bias, transparency, ethics and the environmental impact of machine learning and AI technologies were among the known risks raised by respondents.

There are many training opportunities that can be enhanced by application of digital technology and AI. These require investment and judicious integration into current models for training. Proof of effectiveness and efficacy is essential.

Vascular Surgery Specialty Advisory Committee

Given how rapidly AI and medical technologies are developing, all doctors need grounding in the digital world. Therefore, postgraduate medical training should incorporate more content on digital health, AI and remote care, including the use of technologies such as extended reality, AI and machine learning, to enhance learning experiences and improve training capacity.

That said, given the speed of innovation, consideration should be given to define exactly what training in AI, digital health, machine learning, etc would look like and how it could be properly quality assured and assessed. AI and simulation must be piloted and evidence-based, ensuring they enhance real-world supervised experience rather than replace it.

The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh

Career expectations and system gaps and issues impacting on satisfaction

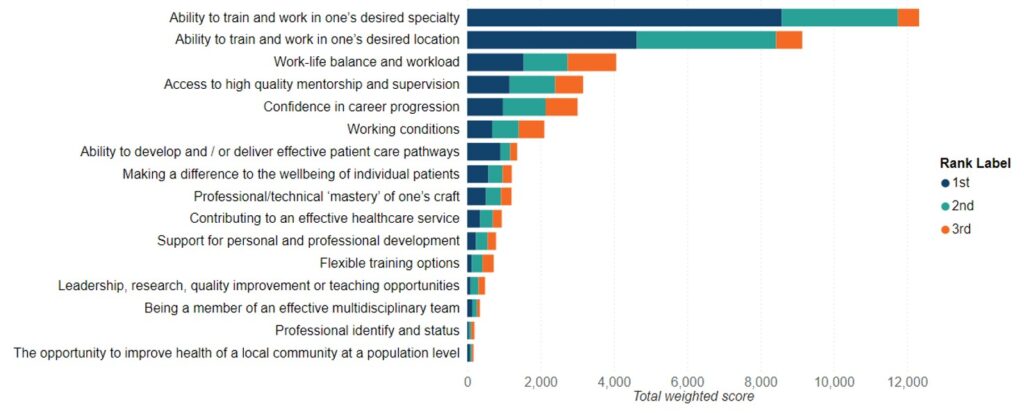

Respondents were asked to select their first, second and third most important and least important factors for a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway from a list of 16 options, plus an ‘other’ option with an accompanying free text box. 6,917 respondents answered this question. Where a factor was ranked first, it scored 3, second scored 2 and third scored 1.

Table 4: Ranking of factors for a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway

| Overall ranking | Most important factors | Sum of total score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ability to train and work in one’s desired specialty | 12,328 |

| 2 | Ability to train and work in one’s desired location | 9,140 |

| 3 | Work–life balance and workload | 4,064 |

| 4 | Access to high quality mentorship and supervision | 3,161 |

| 5 | Confidence in career progression | 3,010 |

| 6 | Working conditions | 2,103 |

| 7 | Ability to develop and/or deliver effective patient care pathways | 1,362 |

| 8 | Making a difference to the wellbeing of individual patients | 1,215 |

| 9 | Professional/technical ‘mastery’ of one’s craft | 1,208 |

| 10 | Contributing to an effective healthcare service | 942 |

| 11 | Support for personal and professional development | 785 |

| 12 | Flexible training options | 722 |

| 13 | Leadership, research, quality improvement or teaching opportunities | 486 |

| 14 | Being a member of an effective multidisciplinary team | 345 |

| 15 | Professional identify and status | 195 |

| 16 | The opportunity to improve health of a local community at a population level | 172 |

| Total | 41,238 |

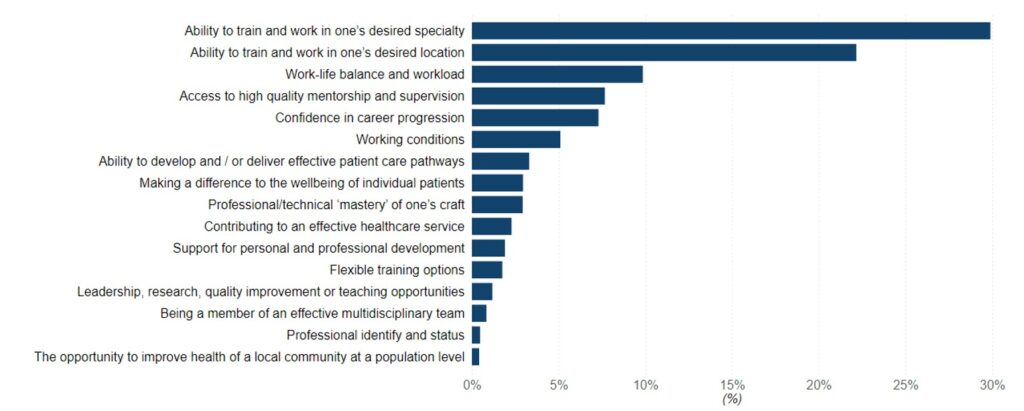

‘Ability to train and work in one’s desired specialty’ was deemed to be the most important factor influencing satisfaction by a margin of 3,188 after weighting. This was the factor most commonly ranked first, with 2,860 selecting this option, and the second most commonly ranked second.

‘Ability to train and work in one’s desired location’ was the second most important factor, followed by ‘work–life balance and workload’. ‘Access to high quality mentorship and supervision’ and ‘confidence in career progression’ were also selected as significant factors impacting on satisfaction.

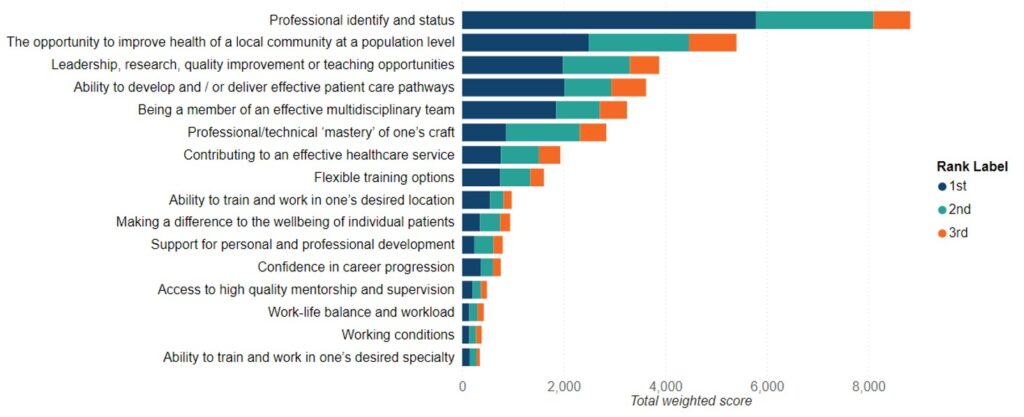

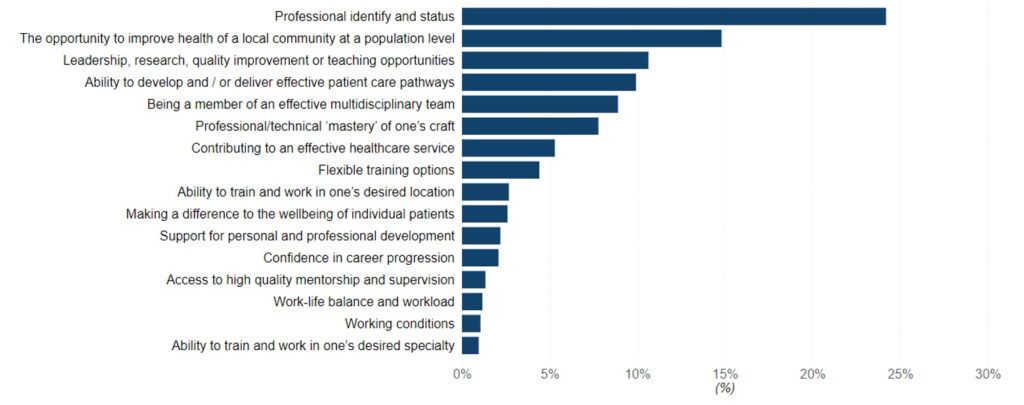

Of those factors selected as least important for a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway, ‘professional identify and status’ received the highest weighted total of 8,824. This was followed by ‘the opportunity to improve the health of a local community at population level’. ‘Leadership, research, quality improvement or teaching opportunities’, ‘ability to develop and/or deliver effective patient care pathways’ and ‘being a member of an effective multidisciplinary team’ were selected as the third, fourth and fifth least important factors respectively.

Figure 1: Most Important Factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of factors based on stakeholder preferences

Figure 2: Least Important Factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of factors based on stakeholder preferences

Figure 3: Most Important Factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Figure 4: Least Important Factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Barriers to a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway

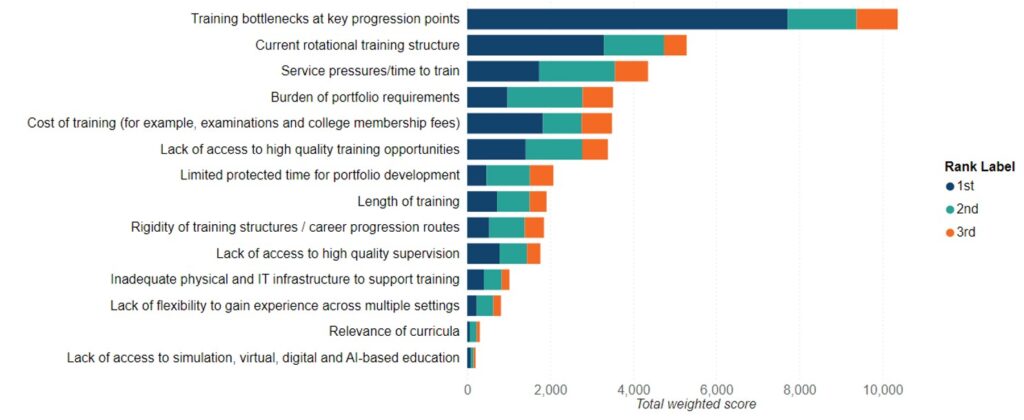

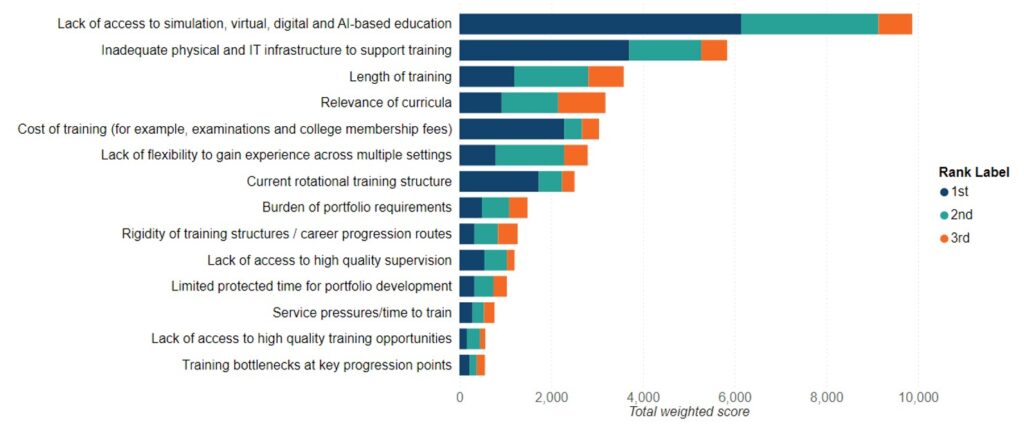

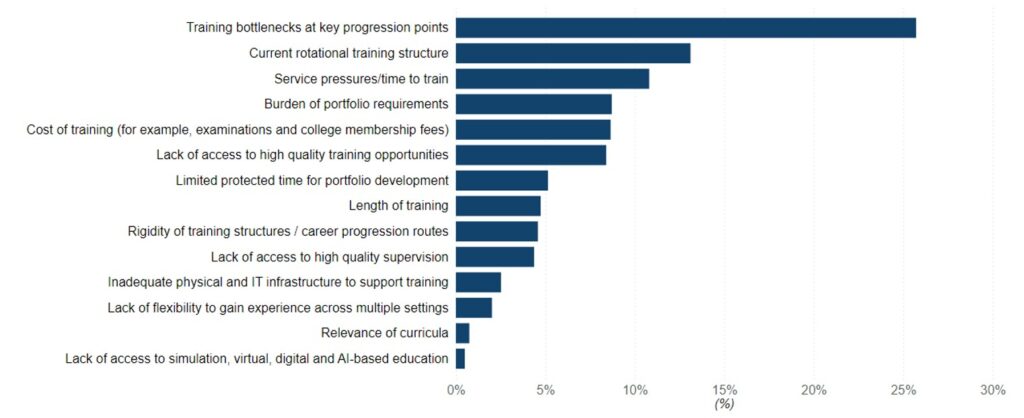

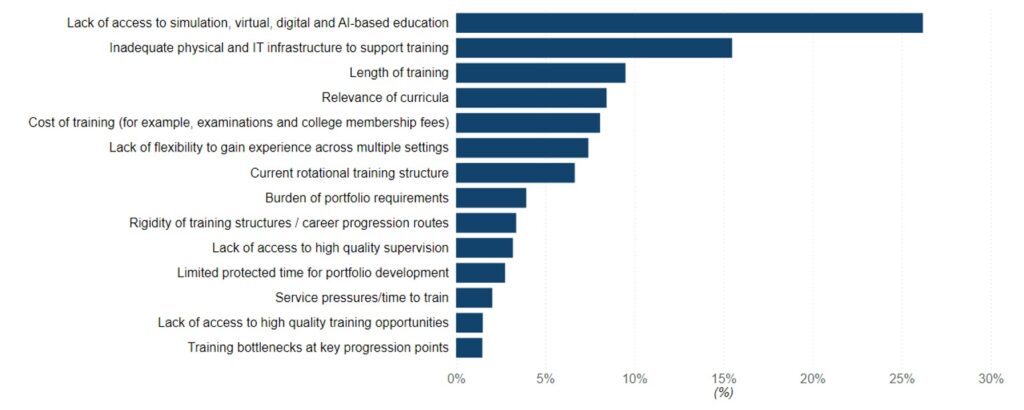

Respondents were asked to select their first, second and third most significant and least significant barriers to a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway from 15 options, plus an ‘other’ option with an accompanying free text box. As for other ranking questions, where a barrier was ranked first it was scored 3, second scored 2 and third scored 1.

Table 5: Ranking of barriers to a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway

| Overall ranking | Most important barriers | Sum of total score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Training bottlenecks at key progression points | 10,367 |

| 2 | Current rotational training structure | 5,284 |

| 3 | Service pressures/time to train | 4,354 |

| 4 | Burden of portfolio requirements | 3,511 |

| 5 | Cost of training (for example, examinations and college membership fees) | 3,485 |

| 6 | Lack of access to high quality training opportunities | 3,386 |

| 7 | Limited protected time for portfolio development (research, quality improvement, teaching, leadership) | 2,074 |

| 8 | Length of training | 1,909 |

| 9 | Rigidity of training structures/career progression routes | 1,847 |

| 10 | Lack of access to high quality supervision | 1,762 |

| 11 | Inadequate physical and IT infrastructure to support training | 1,016 |

| 12 | Lack of flexibility to gain experience across multiple settings | 812 |

| 13 | Relevance of curricula | 303 |

| 14 | Lack of access to simulation, virtual, digital and AI-based education | 201 |

| Total | 40,311 |

‘Training bottlenecks at key progression points’ was considered the most significant barrier by a considerable margin, with 26% of the total votes after weighting (n=10,367). This was followed by the ‘current rotational training structure’, with 13% (n=5,284) and ‘service pressures/time to train’, with 11% (n=4,354). The ‘burden of portfolio requirements’, ‘cost of training’ and ‘lack of access to high quality training opportunities’ were also highlighted as issues, each receiving 8–9% of votes after weighting.

When selecting the least important barriers to satisfaction with the postgraduate training offer, ‘lack of access to simulation, virtual, digital and AI-based education’ received the highest weighted score. With weighting, this received 26% of the total votes on barriers causing the least level of concern (n=9,872). ‘Inadequate physical and IT infrastructure to support training’ was also considered to be of low significance, with 15% of votes (n=5,838). Respondents also indicated that the current ‘length of training’ is of lower concern, with 9.5% of the aggregated weighted vote (n=3,582).

Notably, while ‘cost of training’ received 9% of overall votes for most significant barrier to satisfaction, it also received 8% of votes for least significant barrier. Opinion is evidently divided on this issue and medical specialty and individual economic circumstances are likely to influence a respondent’s position on this matter. There was no notable variation by region, however: training costs were consistently found to be the fifth or sixth most important barrier and fourth to sixth least important barrier in every region of England.

Figure 5: Most Important Barriers for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of barriers based on stakeholder preferences

Figure 6: Least Important Barriers for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of barriers based on stakeholder preferences

Figure 7: Most Important Barriers to a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Figure 8: Least Important Barriers to a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Reform priorities

Respondents were asked to select their top 3 priorities for reforming postgraduate education from a list of 22 options, with 6,700 answering this question. As for all other ranking questions, where a barrier was ranked first it was scored 3, second scored 2 and third scored 1.

Table 6: Reform priorities ranked by total weighted score, number and percentage

| Reform priority | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addressing bottlenecks in training progression at key progression points | 12,183 (60.66%) | 802 (6.01%) | 320 (4.83%) | 13,305 (33.22%) |

| Addressing burnout and improving resident doctor wellbeing | 2,568 (12.79%) | 2,870 (21.51%) | 468 (7.06%) | 5,906 (14.74%) |

| Reform of the specialty recruitment processes to support the specialty preferences of candidates | 630 (3.14%) | 1,400 (10.49%) | 876 (13.21%) | 2,906 (7.26%) |

| Geographically smaller training programmes | 717 (3.57%) | 1,548 (11.60%) | 578 (8.72%) | 2,843 (7.10%) |

| Reform of the specialty recruitment processes to support the geographical preferences of candidates | 612 (3.05%) | 982 (7.36%) | 1,001 (15.10%) | 2,595 (6.48%) |

| Balancing general and specialist training opportunities | 558 (2.78%) | 686 (5.14%) | 230 (3.47%) | 1,474 (3.68%) |

| Creating longer-term trainer/resident mentorship structures | 507 (2.52%) | 702 (5.26%) | 259 (3.91%) | 1,468 (3.66%) |

| Reducing the frequency of rotation within a programme | 369 (1.84%) | 540 (4.05%) | 455 (6.86%) | 1,364 (3.41%) |

| Creating formal pathways for doctors to pursue extracurricular interests (for example, informatics, medical entrepreneurship, academic medicine) | 249 (1.24%) | 634 (4.75%) | 198 (2.99%) | 1,081 (2.70%) |

| Protecting time for educators | 357 (1.78%) | 404 (3.03%) | 309 (4.66%) | 1,070 (2.67%) |

| Greater ability to have capabilities gained in any post counted towards training progression | 234 (1.17%) | 472 (3.54%) | 312 (4.71%) | 1,018 (2.54%) |

| Greater access to flexible working patterns | 141 (0.70%) | 418 (3.13%) | 398 (6.00%) | 957 (2.39%) |

| Giving local health systems greater input into shaping postgraduate medical training placements and specialty numbers | 201 (1.00%) | 370 (2.77%) | 202 (3.05%) | 773 (1.93%) |

| Ensuring access to physical and IT infrastructure required to facilitate training (for example, shared desk space, reliable digital systems | 138 (0.69%) | 358 (2.68%) | 147 (2.22%) | 643 (1.61%) |

| Establishing clearer pathways into medical education, with appropriate incentives | 132 (0.66%) | 332 (2.49%) | 174 (2.62%) | 638 (1.59%) |

| Providing better career coaching/mentorship/ personalised career planning support | 105 (0.52%) | 172 (1.29%) | 198 (2.99%) | 475 (1.19%) |

| Offering targeted incentives to work in underserved areas | 78 (0.39%) | 172 (1.29%) | 186 (2.81%) | 436 (1.09%) |

| Offering better support for doctors pursuing clinical academic careers | 84 (0.42%) | 142 (1.06%) | 116 (1.75%) | 342 (0.85%) |

| Expanding training in community settings | 87 (0.43%) | 150 (1.12%) | 73 (1.10%) | 310 (0.77%) |

| Embedding training to tackle health inequalities and social determinants of health into curricula | 96 (0.48%) | 124 (0.93%) | 69 (1.04%) | 289 (0.72%) |

| Making greater use of extended reality (AI) and machine learning in the delivery of PGME | 24 (0.12%) | 38 (0.28%) | 36 (0.54%) | 98 (0.24%) |

| More curriculum focus on doctors’ competencies in digital health, AI and remote care | 15 (0.07%) | 24 (0.18%) | 25 (0.38%) | 64 (0.16%) |

| Total | 20,085 (100%) | 13,340 (100%) | 6,630 (100%) | 40,055 (100%) |

Notes:

- Reform Priority: Describes the specific area of reform being evaluated.

- 1st Priority Score (%): Proportion of respondents who ranked the reform as their top priority by weighted score.

- 2nd Priority Score (%): Proportion of respondents who ranked the reform as their second priority by weighted score.

- 3rd Priority Score (%): Proportion of respondents who ranked the reform as their third priority by weighted.

- Total Weighted Score (%): Combined score reflecting overall priority across rankings, calculated by assigning greater weight to higher-ranked responses (e.g. 1st priority counts more than 2nd or 3rd).

Each respondent ranked reform priorities by importance. To reflect the strength of each ranking: 1st rank = 3 points, 2nd rank = 2 points, 3rd rank = 1 point. The total weighted score for each reform area is the sum of these points across all respondents, providing a combined measure of overall priority. The percentage weighted score is a way to express the relative importance of each factor as a percentage, based on how respondents ranked them (1st, 2nd, or 3rd). The Percentage Weighted Score shows how much each factor contributes to the overall prioritisation. A higher percentage means the factor was more frequently and highly ranked by respondents. The Percentage Weighted Score was calculated by dividing the Total Weighted Score for a Factor by the Sum of All Weighted Scores divided by 100.

‘Addressing bottlenecks in training progression at key transition points’ was selected as the top reform priority by a significant margin, with 4,061 respondents selecting this as their top priority. This reform option received a total weighted score of 13,305 or 33% of the total aggregated score.

‘Addressing burnout and improving resident doctor wellbeing’ was selected as the second most important reform priority with 15% (n=5,906) of the aggregate vote.

‘Reform of the specialty recruitment processes to support the specialty preferences of candidates’ (n=2,906), introducing ‘geographically smaller training programmes’ (n=2,843) and ‘reform of the recruitment processes to support the geographical preferences of candidates’ (n=2,595) each received 7% of the aggregate vote.

Reflections

The factors influencing satisfaction with the postgraduate training pathway should be considered in the context of barriers to satisfaction. Training bottlenecks are considered to be the most significant issue for graduate doctors at this time. We can therefore assume that the emphasis respondents placed on having the ability to train in one’s desired specialty and location and having confidence in one’s career progression is driven by this issue to some extent.

This is also borne out in respondents’ reform priorities. While the ability to train in one’s desired specialty and location were the top 2 factors influencing satisfaction, the majority of respondents (n=4,061) selected training bottlenecks as their top reform priority. This compares to a significantly smaller number selecting recruitment reform to support candidates’ specialty preferences (n=210) or geographical preferences (n=204) as their top priority.

Bottlenecks are therefore considered to be the main barrier to training in one’s desired specialty and location and to career progression, rather than the current recruitment system design.

Question 17: Additional feedback on a model PGME system

1,074 respondents also shared further written feedback and ideas for delivering an exemplar PGME system. As with previous questions, increasing the overall number of postgraduate training places and prioritising UK medical graduates were prominent themes.

We also received wide ranging suggestions regarding the structure of training, including:

- introducing shorter, more educationally intensive run-through postgraduate medical training – based on international models, such as that in the USA

- shortening foundation training to 1 year, with a 6-month acute medical placement and 6-month surgical placement before direct entry to specialty training

- lengthening foundation training, followed by 2 years’ generalist training to become a generalist. Entry into specialist training would then follow on for a smaller number of doctors, tailored to regional workforce need

- providing a shorter general medicine CCT route, to make this a more desirable career choice for potential applicants

- removing dual accreditation in internal medicine from some specialty physician training routes. To note, the RCP instead advocated for revisiting how the generalist content is delivered, placing less focus on the acute medical take and more on population health and health management

Others proposed measures for providing greater stability and continuity for graduate doctors. Ideas included:

- hub and spoke training models/lead employer arrangements, with a consistent supervisor throughout the programme

- taking geography into greater account; for example, basing foundation training in the same location as the doctor’s medical school or geographically weighting applications according to where an applicant lives, graduated or has previously worked

- introducing smaller geographical footprints for training programmes to reduce commute times or need to relocate

- reducing the frequency of rotations or increasing length of placements

Postgraduate training needs a complete overhaul. We need to train doctors for the future NHS and balancing that with the needs, expectations and ambitions of individuals is tricky. We need to set expectations very clearly from the beginning of the medical school application process.

Medical students and doctors need to see a future in differently organised healthcare system that delivers the healthcare that is needed in the country – from prevention onwards – and that is thoroughly integrated. Training needs to be decoupled from hospitals significantly which means that we cannot rely, to the extent we do now, on the service provision by training doctors.

Senior training faculty member

A number of respondents also made recommendations for ensuring the relevance of training. Some called for a more clinical focus, others for a move away from perceived ‘tick-box’ portfolio requirements to more outcomes and competency-based training (for example, based around the entrustable professional activities), grounded in the skills required of a senior medical decision-maker in that specialty. There was a suggestion that any requirements to author academic publications should be removed from curricula, in favour of focusing more generally on research participation.

Flexibility/personal choice was a common thread, with some calling for the requirements for progression to be less prescriptive and for relevant experience obtained outside prospective training programmes to be better recognised. Within this, there was a sub-theme of delivering greater parity between residents (LEDs) by opening up learning opportunities/supervision and mapping LED skills to levels of training.

Progression should not be based solely on rigid timelines or competitive national scoring. A modern system would recognise the capabilities gained through any NHS service post, supported by a transparent framework for demonstrating competence. The CESR pathway should be integrated into local governance, with formal mentorship and funding, ensuring IMG doctors are not relegated to repeating service roles without clear advancement opportunities.

Locally employed doctor

A smaller number of respondents advocated for reforming recruitment, with some calling for devolved recruitment and the reintroduction of doctor-led interviews to bring the human/interpersonal element back into the process. This was, however, countered by those who acknowledged the role of national selection in reducing bias/variation. From its survey of 1,684 of its members, the RCP highlighted 4 suggestions for reforming recruitment: “broaden assessment methods beyond exams and portfolios, increase interview capacity, increase transparency around scoring, criteria, and ranking, and improve consideration of personal circumstances and geographical needs”.

Finally, we heard that more should be done to protect training from service pressures and free up time to train – with the necessary protected time, resourcing and assurances – and elevated status for educators.

Publication reference: PRN01835