Summary

This document sets out an initial strategy for the development of information about the health of, and healthcare received by autistic people in England, from sources already collected or in the process of being established. Government has announced, in the National strategy for autistic children, young people and adults (national autism strategy), that a cross-government working group is to be set up to develop an action plan for data collection and reporting to monitor progress across all areas. The work set out in this strategy focuses on improving the collection and reporting of data about health and healthcare to feed into this.

As described in the National Autism Strategy, information is key to service development and improvement. Until recently health and healthcare datasets in England have not identified autistic people. This is beginning to change. A national data collection reports the numbers of people whose autism is known to their GP; others report numbers of people using autism diagnosis services and people identified as autistic in mental health services.

Statistical data is needed for several reasons. It underpins development of national healthcare policy, monitoring of policy goals and of local service improvement, estimation of future needs, bidding for and allocating resources, and accounting for delivery of healthcare contracts. For data to be useful locally, it needs to be presented in ways that reflect the local arrangement of the services people use or work in.

The strategy covers information from both services specifically provided for autistic people and wider physical and mental healthcare settings used by everyone. In most cases it can only recognise those autistic people identified as such by their GP, community child health or mental health service. Those identified by GPs represent about 60% of the number of autistic people suggested by work from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey programme, with rates of identification higher in young people and people who also have a learning disability.

The strategy emphasises the importance of information being relevant, understandable, accessible and accurate, with its collection making as little additional demand on clinical or administrative staff as possible. It outlines the data that is currently collected in national datasets from local administrative or clinical information systems, or for which collection plans are in place. It considers how this data can be reported more effectively to demonstrate progress against national policy aims.

It proposes the development of three dashboards, initially in the form of spreadsheets, setting out statistics for:

- autism diagnosis services and transition from child to adult services

- long-term health conditions, healthcare use and mortality for autistic people

- more intensive inputs from mental health services.

These dashboards, which should eventually be publicly available, will allow local managers and senior clinicians to ensure and confirm that statistical returns from their services reflect fully and accurately the work they are doing. The statistics should then begin to show localities where services are performing better or worse than elsewhere.

Introduction

This document sets out an initial strategy for the development of information about the health and healthcare of autistic people in England. It sets out steps that can be taken immediately, or in the near future, to provide richer information about the health needs autistic people face and how effectively current services are meeting them. The National strategy for autistic children, young people and adults (national autism strategy) announced the setting up of a cross-government working group to develop an action plan for data collection and reporting more widely. The developments set out in this strategy should enhance the collection and reporting of data about health and healthcare to feed into this.

The NHS long term plan set out steps the NHS should take to tackle the causes of morbidity and preventable death for autistic people and to improve their experience of using health services. The National Autism Strategy builds on this, emphasising the importance of showing that autistic people are living healthier lives, and evidencing progress in improving health outcomes and reducing the shortfall in their life-expectancy. For these and other issues considered in the NHS Long Term Plan, the NHS needs appropriate reporting mechanisms to be assured that progress is being made.

The National Autism Strategy emphasises improving the recording of autism in routine administrative data to reduce the need for special data collections like the former self-assessment frameworks. This autistic people’s healthcare information strategy (APHIS) proposes three dashboards, mainly drawing on data already specified for routine collection, that should be helpfully informative for local and national service leaders and managers, clinical staff providing care for autistic people, and autistic people and their informal carers.

As a first step towards improving information, these dashboards will allow local managers and senior clinicians to confirm that statistical returns from their services fully and accurately reflect the care they provide. When this is achieved, they should provide valuable information about variations in service provision and activity around the country, and about progress towards meeting targets. For those running or working in services, they should guide service development and improvement work. For those using services and their advocates, they should provide a factual basis on which to review the performance of those services. Further developments will need to be considered in the context of the development of the National Autism Strategy action plan.

The strategy has been developed with the aim of minimising additional burdens on clinical and administrative staff. But if data is to be used and useful, it needs to be:

- Relevant: it should document how effectively and efficiently services are satisfying the needs of their users.

- Understandable: what is being measured and the targets to be achieved should be clear.

- Accessible: easy to find on a public website in forms that those for whom it is intended can easily use and understand.

- Accurate: staff and service users should agree that the data represents services accurately.

Why we need an information strategy

We need a comprehensive approach to gathering information about the health and healthcare of autistic people because:

- Progress nationally and locally needs to be monitored. The National Autism Strategy announced the intention to work across government on an action plan for data collection and reporting to enhance the quality of data on autism across public services. Among other things, this group will want to ensure availability of information to monitor the Strategy’s health aims.

- Unlike its two predecessors, the new National Autism Strategy covers the needs of autistic people of all ages, not just adults.

- Research over the past 10 years has identified substantial health inequalities for autistic people, and monitoring through the national self-assessments has shown wide geographical variations in accessibility of care.

- The range and extent of relevant detail in nationally collected datasets have developed considerably in recent years, making available more useful and informative data.

This strategy suggests what can be done immediately and in the near future to report on autistic people’s health and the healthcare they receive.

Having information about the availability and performance of services does not in itself change anything. However, if well-presented and reliable, statistical evidence can identify the particular needs of autistic people, and the extent to which these are being met. This is essential for local service improvement work. It also offers information for people who use services.

Scope

Autistic people should be able to obtain the same health services as anyone else with similar needs and should expect similar outcomes. Ideally, a health information strategy should document all the health and healthcare needs of all autistic people, of all ages; children and young people (CYP) as well as adults. In practice, it is only possible to collect information about people identified as autistic in healthcare records. There are broadly two sets of healthcare records, those kept by GPs, which give an overview of all the health issues for individuals, and those kept by hospitals and community health services which mainly record details of specific periods of care individuals receive for specific problems.

The most obvious way to identify autistic people is through GP patient records. For many long-term conditions GPs maintain registers of affected patients. These allow them to call people for relevant checks. They are not currently required to maintain registers of autistic people, (though this possibility has been under consideration for several years) but GPs can record that patients are autistic in clinical case notes. Data collected by NHS Digital in 2020 (described in more detail below) suggests that the number identified by GPs is about 60% of the likely number suggested by the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, with identification very much more common in younger than older age groups. This is described in more detail below. The establishment of autism diagnosis services for adults over the past decade should increase the completeness of identification, but probably not quickly or completely.

GP records are therefore a source of information about many aspects of the health of autistic people. They can provide information about all health conditions GPs diagnose and manage for people they have identified as autistic, as well as recording of death when it occurs. However, they do not provide comprehensive or detailed information about care provided to autistic people in hospitals (including accident and emergency departments) or community health services, or about the causes of death. Statistical data for these areas are routinely collected in a series of NHS datasets and in the national register of death certificates, but unfortunately most of these sources do not systematically identify which of the people described are (or were) autistic. Their focus is on the specific conditions being treated and staff are only likely to record other conditions where they consider it relevant.

Mental health services are an exception to this, first because the nature of their work means that where patients are autistic this is almost always relevant, and second because some data collections about mental health services specifically ask this.

Accessibility and accuracy

Indicators need to be provided for real service geography

Local service managers and clinical leads are likely to have many uses for accurate timely statistics about the care of autistic people in their services. These include:

- monitoring quality and progress towards policy goals

- estimating the scale of likely future needs

- agreeing and allocating resources within the provider

- accounting for financial payments from commissioners.

To be locally useful for these purposes, statistical presentations need to relate to the administrative arrangements, particularly the geography, of local services. At present the lowest level for which statistics are published is usually commissioner or provider organisations. The size of both of these groupings means they commonly encompass several whole services. Where possible, statistical presentations need to support breakdown to the levels at which services are organised and delivered. They also need to support the newer geographies of integrated care systems currently being introduced, and to develop in step with future changes in organisational structures or boundaries.

Data needs to be accurate and complete

At present there are important gaps in the data reported by some providers. For example, many autism diagnosis services are not reporting diagnostic data, and many mental health care inpatient providers are not reporting on their use of restrictive interventions. Discussion of some examples of reported data with local service leaders suggests there are also other, less obvious, divergences between the way autism referral and other codes are being used by providers and interpreted in national reporting. Once data presentations are available that can be related to local services, local clinical leaders and their information specialists will need to review their validity and where necessary address problems with the data they are submitting.

Ethnic group issues

Where possible, reports on the health and care of autistic people should show the position for different ethnic groups. This is likely to be problematic given the small numbers of people involved and the incompleteness of recording of patients’ ethnicity in some data sources. As a minimum, reporting should describe national patterns of care by ethnic groups and local levels of completeness of recording of ethnicity.

Improving the data

Services are unlikely to be able to fulfil these requirements for all areas of autism health data in a single step. This strategy envisages that information on autistic people’s health and healthcare will be reviewed in three major groupings: diagnosis services and transition, general healthcare and mortality, and mental healthcare. For each of them, initial audit data will be provided in the form of a preliminary dashboard, which will be shared with commissioners and providers of autism services. These will show caseloads, activity and where possible outcomes for providers and commissioners at the lowest levels that can be usefully identified.

Each of the three planned dashboards will initially include a few measures that reflect the highest priority concerns. Where these show surprising differences between areas providers will be able to review whether the underlying data is being reported consistently. Dashboards will also include others measures which show the data being submitted by providers to allow local checks on their completeness and accuracy. As the quality of data submissions improves, further measures will be added, along with indications of their strengths and weaknesses.

- Diagnostic pathways dashboard: High priority items: numbers and rates of referrals to, and contacts and diagnoses made in, autism diagnosis services. Later additions may include contact patterns for people referred to services, including for post-diagnostic support; waiting times from referral to contact and from referral to conclusion; which (if any) coded assessment tools are used; and how commonly people are referred onwards to another service.

- General health dashboard: High priority items: numbers and proportions of people identified by GPs as autistic (by age and sex (the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ are both used in this report and its annex. In each case the choice of term reflects the specification of the data source being described) and overall general mortality rates and life expectancy. Numbers of identified deaths are likely to be too small for mortality rates to be reportable at local level. Initial measures will also include rates of epilepsy, prescribing of some psychotropic medications and uptake of breast cancer screening. When possible, later additions may include rates for other important health issues such as obesity, high blood pressure, COVID-19 immunisation, uptake of other types of cancer screening and health checks.

- Mental healthcare dashboard: High priority items: number of autistic people in inpatient mental health care for more than a year (including numbers detained under Ministry of Justice restriction orders), coverage of commissioner oversight visits, use of restrictive interventions and of adverse events among inpatients, including assault and self-harm. For integrated care systems, rates of autistic people, with and without learning disabilities, receiving different levels and types of community care, patterns of admission within long term care plans, and use of reviews (Care and Treatment Reviews (CTRs) for adults and Care, Education and Treatment Reviews (CETRs) for children and young people); proportions of longer-term inpatients for whom discharge plans are underway; and rates of admission, distinguishing admissions for treatment of mental illnesses from those for behavioural management or forensic reasons.

For each dashboard there will be an initial review phase. This will allow local providers to see the picture for their services as they are currently reporting it. Local clinical leads will be encouraged to review the data with information leads and regional autism leads. This process should seek to clarify:

- whether the reported data is complete and accurate

- whether and how the current administrative and geographical reporting boundaries need to be developed to reflect the existing service arrangements

- how well the choice of presentations reflects local service improvement concerns.

NHS regional learning disability and autism teams will be asked to collate responses from the areas they cover in relation to these three issues. Drawing on the findings, the three dashboards will be revised to set out the currently available data, giving whatever cautions are indicated.

As the quality of these dashboards improve, relevant data from the dashboards will be published.

Timescale

Initial versions of the three dashboards will be produced in autumn 2022 and shared with systems and providers. The intention is that the diagnostic pathways and mental healthcare dashboards should be updated initially every three months. The general health dashboard data will initially be updated annually as the data sources it draws on are mainly annual.

Plans for longer term developments will be considered in the context of the cross-government action plan mentioned above.

Datasets currently or potentially available

As indicated in the National Autism Strategy, government’s intention is to move towards data collection and reporting through routine statistical datasets. This section sets out the most important datasets from which data on autistic people’s health and healthcare provision can currently, or foreseeably, be drawn.

Each of the datasets is intended to report all the clinical activity for a set of services. All the NHS care received by autistic people should be documented in them. However, in each one reporting on the care of autistic people requires a way to identify which patients are autistic. This issue is described for each dataset.

Health and care of people with learning disabilities (HCPLD)

The HCPLD dataset provides an annual snapshot of many aspects of the health of people with learning disabilities, comparing them to people without learning disabilities. In the 2020 collection, numbers of people with and without learning disabilities known to their GP to be autistic (by age group and sex) were reported. For the 2021 collection, the information about people identified by their GP as autistic was extended giving overall death rates, rates of diagnosed epilepsy, rates of prescribing of antipsychotic or benzodiazepine drugs and, for autistic women, uptake of breast cancer screening. These collections all distinguish autistic people with and without a learning disability.

For information governance reasons, this data is collected in a fully anonymised form. Although the design allows considerable flexibility in analysis, this means that the data cannot be linked to other datasets to give a fuller picture of the care or outcomes for the autistic people covered.

At present the data is collected for only just over half the population of England. This is because some major suppliers of GP practice information systems do not support the data extraction. Coverage is therefore patchy with some areas almost fully covered and others covered sparsely or not at all.

GP data for planning and research (GPDPR)

In May 2021, NHS England announced their intention to establish a regular collection of statistical data covering patients’ health, illnesses and healthcare – the GPDPR. This approach, which builds on the emergency system established to manage the COVID-19 pandemic, would replace the General Practice Extraction Service that currently supports the HCPLD, potentially offering a much wider range of information. At present this development has been paused for consultation.

Mental health services data set (MHSDS)

The MHSDS is the principal dataset documenting the activity of mental healthcare providers working under contracts for the NHS in England. It covers inpatient, day patient, outpatient, community-based or home-based care, and group therapies. It includes the activity of autism diagnosis services and child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). The dataset aims to record all referrals to these and their outcomes. Care providers report data monthly to NHS Digital, which maintains an archive.

- The care autistic people receive can be identified directly in this dataset by looking for all people who have been given an autism diagnosis at some point in time. This could potentially be widened by looking for people who have been given an autism diagnosis in other NHS hospitals or community services. At present it is not possible to extend this further to include others identified as autistic by their GP.

Community services data set (CSDS)

This dataset covers activities of most community-based clinical specialties other than mental health care. Autistic adults use community health services for all the same reasons that other adults do. This dataset is therefore relevant for exploring the community-based healthcare received by older autistic adults or those with long-term health needs. Where autistic people have had this diagnosed in other hospitals or community health services datasets, such as the MHSDS, it should be possible to link this.

The second reason this dataset is important is that, since October 2017, it covers the activity of community child health services. Before that date, there was a separate children and young people’s health services data set. Assessment and management of developmental delays and emotional or behavioural problems in children and young people are likely to happen both in child health services (reported through the CSDS) and in CAMHS (reported through the MHSDS). Identifying the care provided to autistic children and young people using this dataset could be done either directly from records of autism in the dataset or by linkage to other hospital or community services datasets.

Assuring transformation (AT)

The AT dataset documents mental health inpatient care for people with a learning disability and autistic people, including data on admissions and discharges and on care (education) and treatment reviews and commissioner oversight visits.

It complements the MHSDS (which gives a hospital provider perspective) by giving the commissioner’s view of this activity. It was established in response to the finding from the learning disabilities inpatient censuses between 2013 and 2015 that no active commissioning was being undertaken for a substantial group of patients.

NHS Digital stores the information about individual patients in this dataset, and commissioners are expected to update it as developments occur. Records identify whether each person in a mental health inpatient setting is autistic, has a learning disability or both.

Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT) dataset

IAPT services are psychological services for people with common mental health problems. They are usually led by clinical psychologists and in some places are provided by organisations that are not mainstream mental health services. The IAPT dataset is separate from the MHSDS and designed differently. It is rich in clinical detail about symptoms and progress, but does not provide a comprehensive view of patients’ previous mental health diagnoses.

Until recently it was not possible to identify autistic people in the IAPT dataset. However, in autumn 2020, a way to record patients’ previous medical history (previous diagnoses) was introduced.

Primary care mortality database (PCMD)

This database is part of the national mortality dataset. It contains a record for each deceased person whose death is registered in England or Wales, including their age, sex, place of death and other administrative details, and the medically certified causes of death. It is supplemented with NHS identifiers for deceased people to allow analysis in relation to NHS and local government geographies. If linkage to autism diagnoses in general practice becomes possible through the GPDPR, this will allow analysis of autistic people’s death rates by cause of death.

Patient survey datasets

The NHS and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) have major national programmes for surveying the experiences of people who use health services. The largest, run by an independent polling organisation for the NHS, surveys people’s experiences of using GP services. This survey asks respondents if they are autistic, thus allowing comparison of the experiences of autistic people with those of non-autistic people.

The CQC runs frequent smaller surveys of the experience of patients using other NHS services. These cover five areas of care (general hospital, community mental health, maternity, children and young people services, and urgent and emergency care), in most cases annually. The most recent rounds of these surveys have included a specific question asking whether the respondent is autistic or has an autism spectrum condition.

As noted, these survey datasets ask individuals to identify if they are autistic themselves. This may therefore report on a different group of people to the datasets dependent on GPs or other clinical staff making this determination.

Other data sources

The sources outlined above document aspects of patients who are receiving healthcare and the care provided to them. To monitor improvement in the healthcare provided for autistic people, other types of information are also needed. Some relate to the availability of services and facilities in each area of the country, some to the numbers of staff in professional groups and their training in the needs of autistic people, and some to wider contextual issues of available social care and other community resources.

Number of people with autism known to GPs

The section on the scope of data collection noted that the NHS can only realistically monitor the health of autistic people whose autism is known to the health service. As a final note to this strategy it is helpful to consider how many autistic people are identified this way as this gives some indication of possible limitations to the completeness of the picture the indicators described are likely to give.

The annual collection of data from general practices to document the health and care of people with a learning disability is described above. As noted, the 2019/20 data collection included the number of individuals with and without a learning disability recorded by their GP as autistic. This is the first official count of the number of people, of all ages, diagnosed as autistic by the health service. It can be looked at alongside the number- identified as autistic in the largest English population survey, the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS).

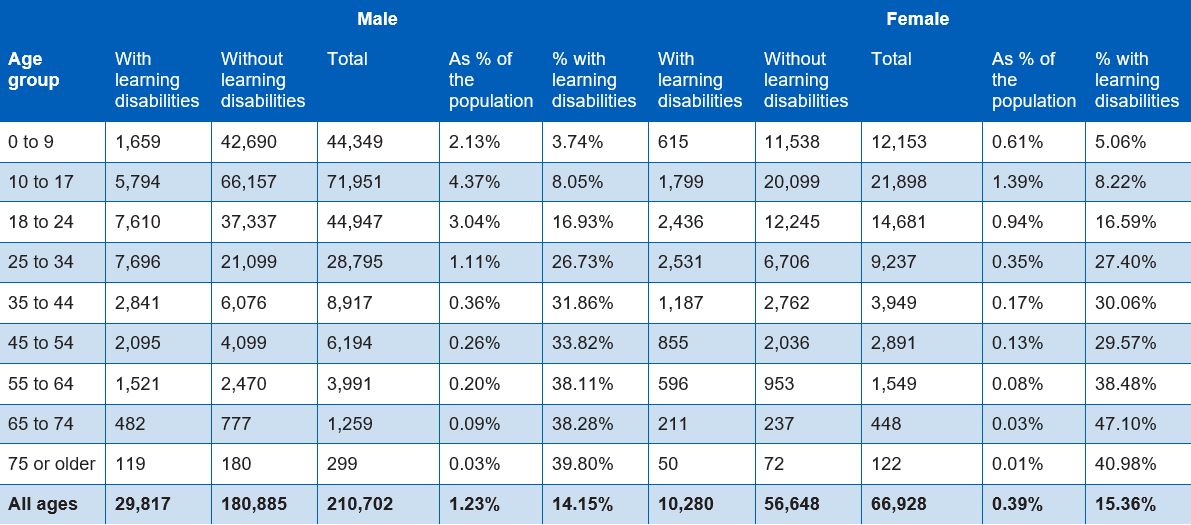

Table 1

Numbers and proportions of people registered with GPs identified as autistic in practices contributing to the health and care of people with learning disabilities (HCPLD) data collection, England, March 2020. Data from NHS Digital.

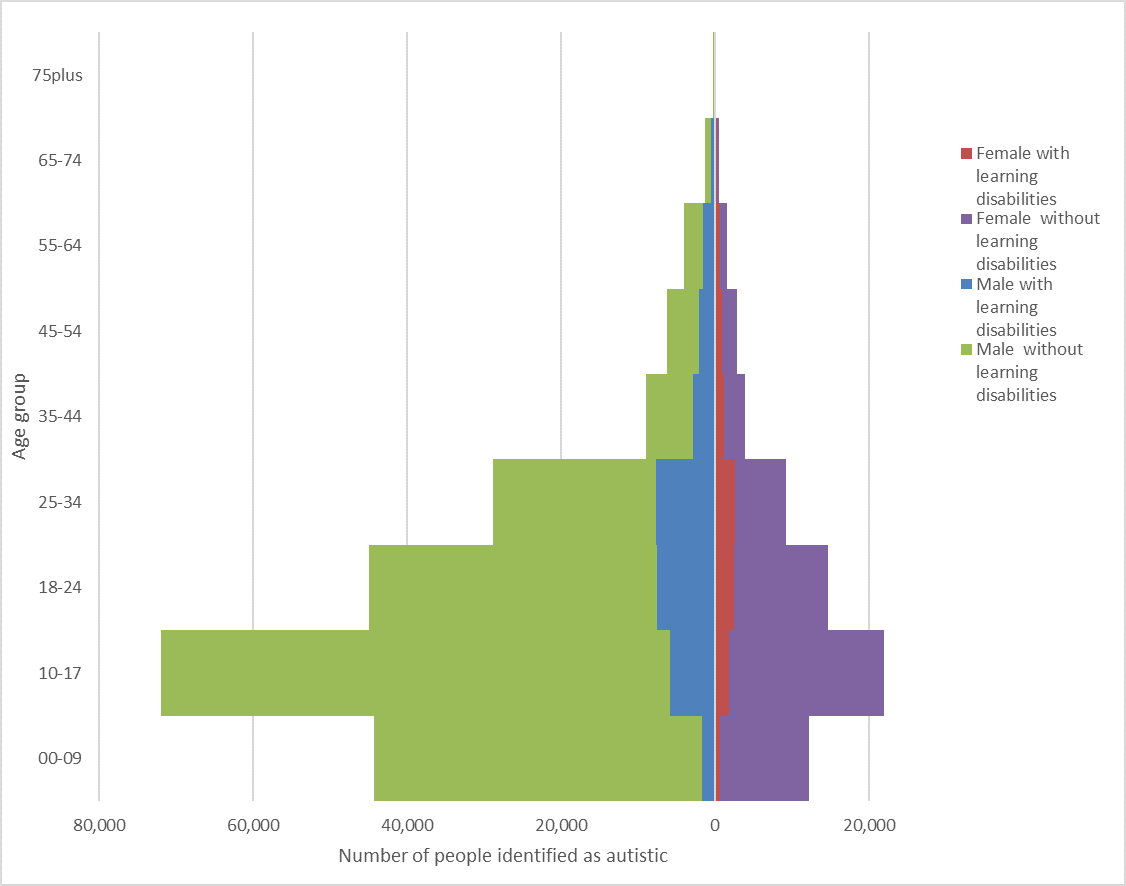

Figure 1

Population pyramid for autistic people registered with GPs in practices reporting data in the health and care of people with learning disabilities (HCPLD) dataset, March 2020.

Figure 1 above shows a population pyramid for people identified as autistic with or without a learning disability. Men outnumber women, and younger people are much more likely than older to be identified as autistic. The number identified as autistic per 100 population varies considerably between areas. In the figures reported from CCGs in 2021, for people with learning disabilities the lowest quarter of CCGs identified fewer than 19.4% as autistic whilst the top quarter identified more than 26.8%. Corresponding figures for the proportion of people without learning disabilities identified as autistic were from 0.5% to 0.8%.

The high-capacity programmable logic devices (HCPLD) dataset in 2019/20 was collected from general practices covering 56.6% of the population of England.

The proportion of autistic people identified as also having a learning disability also varies considerably with age. It is under 10% in children and young people but around 40% in those aged over 55. This finding is particularly important in relation to mortality indicators as research indicates very much larger excess mortality associated with autism and learning disabilities combined than with autism alone (Hirvikoski T, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Boman M, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Bölte S. Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 2016; 208: 232–238. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192).

Importance for the strategy

Knowing the likely numbers of people with autism in a local area provides useful information about:

- the resources likely to be needed to roll out programmes such as health checks for autistic people

- the extent to which the number of people receiving a health check reflects the number in the target population

- how calls for services for autistic people are likely to develop as younger groups in whom autism has been more completely identified grow into the age groups with greater health needs.

The current data analyses of GP case notes do not consider the ethnic profile of autistic people. Analysis of school special educational needs data indicates that, at least for children, there are substantial differences in rate of identification of autism between ethnic groups (Strand S, Lindorff A. Ethnic disproportionality in the identification of Special Educational Needs (SEN) in England: Extent, causes and consequences. University of Oxford Department of Education, 2018). It will be important to explore whether similar differences are found in health service data and if so, whether this reflects differences in the prevalence of autism or its recognition.