Classification: Official

Publication reference: PR1849

1. Foreword

The HIV Action Plan sets out a programme to achieve the government’s commitment that by 2030 we will have achieved zero HIV transmissions in England. We are well underway to achieving this ambition and I believe that emergency department opt out testing in very high areas of diagnosed HIV prevalence will play an important part in helping us to do so. This approach to HIV testing builds upon pilot studies and evaluations undertaken over the past decade. Opt out testing is confirmed to be effective both in identifying and linking to care those people with HIV infection who were unaware of their diagnosis or had become disengaged with care.

By normalising testing as part of an emergency department (ED) attendance when blood is drawn, we help reduce HIV stigma. We reach communities which are currently underserved by testing opportunities and reduce the number of people presenting with a late HIV diagnosis. This is a highly cost effective initiative which improves people’s health and wellbeing outcomes, save the NHS valuable funds through avoidance of expensive inpatient care, and avoid onward transmissions.

I am pleased that we have taken the opportunity to partner with the NHS England Eliminating Hepatitis C Programme to introduce hepatitis B and hepatitis C testing in many locations. We are delighted that the project has already identified hundreds of people who are being linked to care. This has further underscored the utility of this testing approach and its benefits to improving population health.

This report shares the findings of the initial four months of the programme’s implementation, reflecting on its design, delivery and early outcomes. It represents the collaborative work and efforts of hundreds of colleagues across the NHS, statutory agencies, local government and the voluntary and community sector, for which we are grateful. The early lessons confirm and reinforce the power of partnerships, collaborative programme implementation, and empowered communities coming together to accelerate our nation’s progress in ending HIV transmission.

Professor Kevin Fenton

HIV Adviser to the Government, Director, Office for Health Improvement and Disparities London, Department of Health and Social Care

Regional Director of Public Health NHS London

The NHS England Hepatitis C Virus Elimination programme is working towards a shared goal of eliminating hepatitis C as a major public health issue in England, ahead of the World Health Organisation (WHO) goal of 2030.

Since it was established in 2015, the programme has worked tirelessly with partners across the health service, government, charitable and pharmaceutical sectors to deliver a series of world-leading ‘elimination initiatives’ to find potential patients, test for infection and offer everyone living with hepatitis C curative treatment.

The NHS’ drive to find and treat people at high risk of death from hepatitis C has led to a dramatic 35% reduction in deaths (from 482 per year to 314 per year). Furthermore, the programme has delivered a remarkable 52.9% reduction in the number of liver transplants since 2015.

To complete our mission to eliminate chronic hepatitis C in England, the NHS has further expanded testing and treatment services, including a number of emergency departments as outlined in this report. We aim to find all of those who remain living with hepatitis C.

Mark Gillyon-Powell

Head of Hepatitis C Elimination programme, NHS England

This report is dedicated to the memory of Aimee Beckett, Emergency Department HIV Testing Nurse at King’s College Hospital, who sadly died earlier this year. She will be remembered for her immense contribution to ensuring ED HIV testing is a part of routine practice at King’s, her enthusiasm and her sense of humour.

2. Executive summary

This report describes the progress, challenges, results and learning of the first 100 days of an initiative to implement opt out testing for HIV, hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) in emergency departments (EDs) in the parts of England with the highest diagnosed prevalence of HIV infection.

The initiative was created following the government’s announcement that it would provide new funding to roll out ED opt out testing in the areas of highest diagnosed HIV prevalence which was set out in Towards zero – an action plan towards ending HIV transmission, AIDS and HIV-related deaths in England – 2022 to 2025. The HIV Action Plan was developed in response to the independent HIV commission’s report focus of ‘test, test, test’, and widespread campaigning by key stakeholders.

There is extensive evidence that ED opt out testing is both cost effective and may address some barriers to access experienced by some groups who are less likely to proactively engage with and receive testing via sexual health services. It will therefore play a crucial part of England’s HIV Action plan to end HIV transmission in addition to contributing to the World Health Organisation’s 2030 goals of zero transmission of HIV, and the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat.

This project started with a focus on HIV. However, the opportunity arose to partner with NHS England’s HCV Elimination programme, which is funding a small number of hospitals to implement HCV testing in their EDs. This has enabled the implementation of wider, blood borne virus testing to include HBV, across the selected ED sites in several of the newly formed integrated care systems.

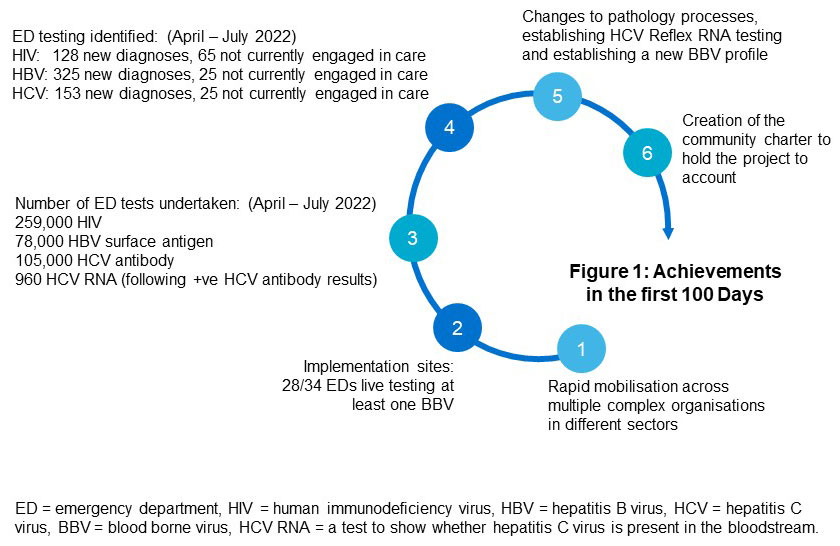

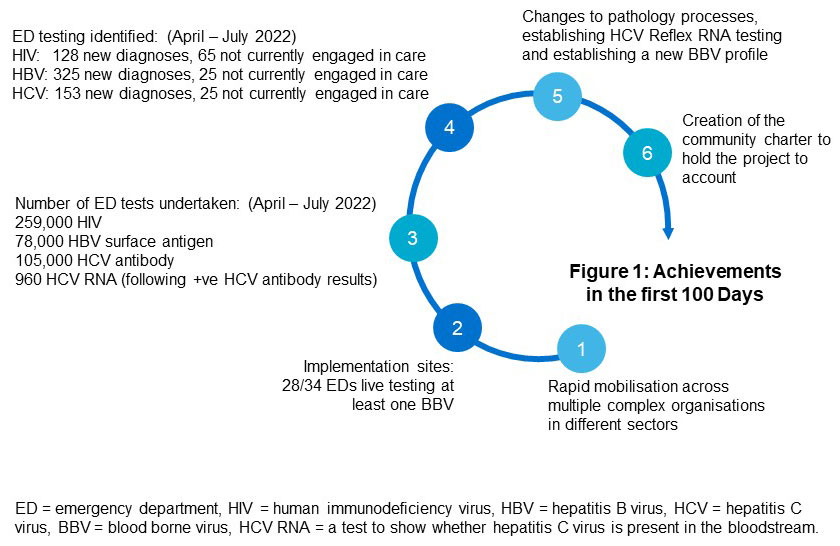

The achievements in the first 100 days include the rapid mobilisation of systems to implement testing, with over 250,000 HIV tests and over 100,000 HCV antibody tests delivered (April – July 2022). This testing resulted in identification of over 500 people with previously unknown (or unrecognised or undiagnosed) blood borne virus (BBV) (figure 1). Key process changes to pathways and laboratory test profiles have also been made to support the implementation of opt out testing.

New defined as: new to that clinic and person not disclosing that they are under care elsewhere. All results subject to validation with UK Health Security Agency.

Read an explanation of figure 1.

There is still much to do to reach our targets of extending opt out testing across all sites and achieving 95% uptake of BBV testing amongst those who are having their bloods taken.

Partnership working with Hepatitis C Operational Delivery Networks (ODN)s, NHS trusts, pathology networks, IT teams, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and community organisations has enabled redesigned pathways, new testing profiles and new reporting systems.

UKHSA and its academic partners will lead on collecting and monitoring data and undertake an evaluation of the impact of this project from a public health perspective, including:

- The challenges faced by those implementing the testing and how they have been overcome.

- Cost effectiveness of each test by BBV in relation to new positivity.

- Extent new diagnoses are found versus those disengaged from care.

- Extent those newly diagnosed and lost to care are reintegrated into care.

- Assessment of the extent that testing in this setting reduces health inequalities in BBV testing uptake. This is vital in informing any decision regarding extension of ED opt out testing beyond the areas of highest incidence of diagnosed HIV.

The community sector is providing culturally appropriate community and peer support, recognised as key to improving the health and wellbeing outcomes of people living with a blood borne virus. Community services and peer support also increases the likelihood that people will both access care and continue treatment in the future. Increasing access to community services and peer support has been included in the project, including a recommendation from NHS England – London region to London integrated care systems (ICSs) that 10% of funding should be used to commission effective community and peer support, and data will capture how much of this has been implemented.

3. Introduction

The NHS in England is steadfast in its ambition to reduce the levels of HIV, hepatitis C (HCV) and hepatitis B (HBV) transmission to improve public health outcomes contribute to the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2030 goals of zero transmission of HIV, and the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat.

Significant inequalities still exist in identifying those who are living with HIV, HCV and HBV and addressing these inequalities is paramount if we are to achieve the targets set by the WHO. Tackling these challenges requires reaching those who do not test in traditional settings such as primary care or sexual health clinics, either because they are not accessing or not being offered tests when they do attend. Vulnerable people disproportionately attend EDs and opt out testing at scale in EDs is a key intervention to meet this need.

The ED opt out testing project aims to deliver a significant increase in testing. The project was started following the publication of the government’s report ‘Towards Zero – An HIV Action Plan for England 2022-2025’ (the HIV Action Plan).

To maximise impact, a partnership approach was adopted with the national HCV Elimination programme, to combine funding and establish a joint blood borne virus (BBV) testing approach in EDs for HIV, HBV and HCV. These BBVs impact overlapping population groups and follow similar detection, diagnosis and care pathways. Adopting a combined BBV approach is not only an efficient approach to testing and diagnosis, but also offers significant benefits to patients and wider population as we work towards meeting the 2030 targets.

This report documents the progress of the first 100 days of routine opt out testing in EDs; the background, key aims, progress and key achievements are described, using data on testing, uptake and results, patient stories and observations from clinicians and community. It details the key challenges and learning so far and sets out the next steps for the project.

As we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic and with the NHS facing unprecedented challenges, this is a story of innovation, success and hope in an area where the NHS can genuinely be regarded as a world leader.

4 Background and case for change

4.1 Policy landscape

In December 2020 the HIV Commission launched its report on how to achieve the WHO target of zero HIV transmissions in England by 2030. The commission, supported by the Terrence Higgins Trust, the National AIDS Trust and the Elton John AIDS Foundation, consulted with community organisations, people living with HIV, clinicians and policy makers and UKHSA to make three key recommendations:

- England should take the necessary steps to be the first country to end new HIV transmissions by 2030, with an 80% reduction by 2025. Jointly the Department of Health and Social Care and the Cabinet Office should report to parliament on an annual basis the progress toward these three goals.

- National government must drive and be accountable for reaching this goal through publishing a comprehensive national HIV Action Plan in 2021.

- HIV testing must become routine – opt out, not opt in, with HIV testing across the health service

The ED testing recommendation was informed by evidence from the Elton John AIDS Foundation Social Impact Bond ‘Zero HIV’ ED programme testing at Kings College Hospital and University Hospital Lewisham, and other published ED testing work, which provided vital evidence of the effectiveness of ED HIV testing.

The government’s HIV Action Plan built upon these recommendations, setting a commitment to end new transmissions of HIV, and reduce AIDS / HIV related deaths and stigma by 80% by 2025. Under the leadership of Professor Kevin Fenton, it is part of a wider ambition to end HIV transmission in England by 2030. As part of the HIV Action Plan the government and NHS England committed £20 million of funding over three years to expand HIV opt out testing in EDs in the areas of highest diagnosed HIV prevalence: London, Brighton, Manchester and Salford. Blackpool was subsequently included. The ED HIV opt out testing project was launched in April 2022, building on existing ED testing in some sites, see table 1 below.

Table 1: ED sites already testing prior to April 2022 (not all on opt out basis)

| Test | Testing sites |

| HIV only | Blackpool Victoria Hospital, Charing Cross Hospital, Croydon University Hospital, Homerton University Hospital, King’s College Hospital, Kingston Hospital, Newham General Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, St Thomas’ Hospital, St George’s Hospital, St Helier Hospital, St Mary’s Hospital, University College Hospital, University Hospital Lewisham, West Middlesex University Hospital |

| HIV + HCV | Manchester Royal Infirmary, Newham Hospital, The Royal London Hospital, Wythenshawe Hospital. |

| HIV + HBV + HCV | Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, North Middlesex Hospital. |

For London sites the plan is to roll-out HBV and HCV testing alongside HIV, with other areas considering this according to prevalence and resources.

4.2 Seizing the opportunity: partnering with the HCV Elimination programme

To maximise the opportunity afforded by the HIV Action Plan funding for HIV opt out testing in EDs, the Director of Commissioning for London’s specialised commissioning office, proposed a combined BBV approach to include HBV and HCV testing alongside HIV testing in London to the NHS England HCV Elimination team.

The HCV Elimination programme was established in 2015 with the aim of meeting the WHO’s elimination of HCV goal by 2030 in England. It has funded a wide range of case finding approaches, including piloting HCV ED testing in areas of high HCV prevalence (see footnote 1). The HCV Elimination programme funded £3.85m for London ED testing 2022/23 with a further £3m nationally to areas of high prevalence (see footnote 2). The funding for all treatment pathways, treatment drugs and community peers for hepatitis were centrally commissioned already by the HCV Elimination programme, in addition to the allocation provided to integrated care boards for testing and diagnostics.

There is a time limited opportunity to increase HCV testing. In 2015 the NHS delivered its single largest medicines procurement with three pharmaceutical organisations, a deal worth almost £1 billion over five years. When the deal was struck, England was one of the few countries in Europe where all HCV positive patients could access the new Direct Acting Antivirals (DAA) treatments for HCV, which have a cure rate of over 95%. By ensuring all patients can access DAAs, deaths from HCV, including liver disease and cancer, have fallen by 35%, achieving the global target of reducing HCV related deaths below 2 per 100,000. HCV as a reason for liver transplants has fallen by 52.9%.

This provides a window of opportunity to urgently increase testing whilst the costs are low and before the price of drugs goes back to pre-procurement deal levels. Whilst high prevalence areas for HIV and HCV have some overlap, there may be a need for further ED HCV testing in areas of low HIV diagnosed prevalence.

4.3 Undetected BBVs, people lost to care and late diagnosis in England

Despite free and highly effective treatment for HIV, HBV and HCV, many people remain undiagnosed. Current estimates suggest 4,660 people are living with undiagnosed HIV (see footnote 3), and an estimated 80,000 people are believed to be living with chronic HCV infection (see footnote 4) and around 180,000 individuals are living with chronic HBV.

The impact of this on members of our communities is stark. For instance, Parry et al reported that in 2017, during the ‘Going Viral’ initiative at the Royal London Hospital and a number of other trusts, 12% of patients found to have HBV who needed a link to care (either new diagnosis or lost to follow up) were late diagnoses with evidence of cirrhosis or hepatocellular cancer.

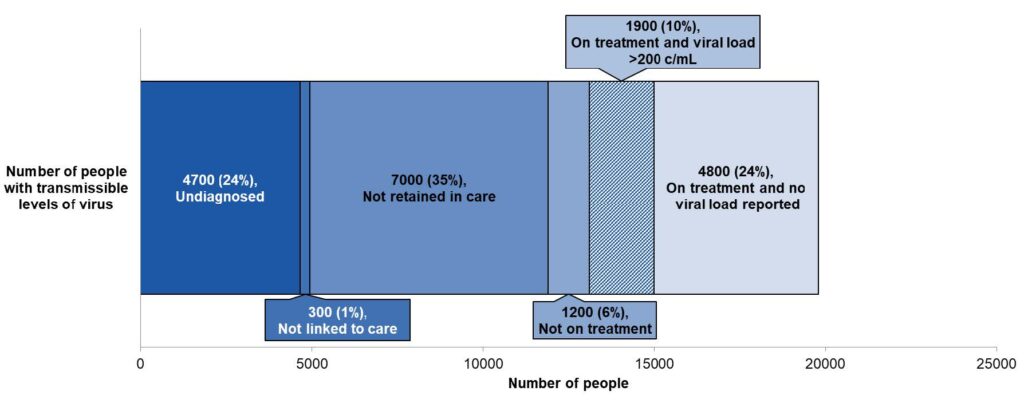

The key issues of achieving links to care, and ensuring that people are retained in care, can be challenging, and often the chances of achieving these outcomes can be improved by the provision of holistic support. For HIV, this means rapid transfer to HIV care and treatment; for HBV it means some people will require lengthy ongoing treatment and for some others ongoing monitoring. For those with HCV it means medication until they complete a course of curative treatment and ongoing support with and access to prevention and treatment whilst still at risk of re-infection. The number of people with a transmissible level of HIV virus, not retained in care, (those who have left care and can no longer be traced) is now greater (7,000) than the number of undiagnosed people living with virus (4,660).

The chart below shows the estimated number and proportion of people living with HIV who had transmissible levels of virus in England 2020, rounded to the nearest 100. This data is from UKHSA 2021.

Of the people with transmissible levels of virus, 24% are estimated undiagnosed; 35% are not retained in care; 24% are on treatment and have no viral load reported.

Many individuals with BBVs are diagnosed at a late stage, potentially when their health is already seriously affected. The number of people diagnosed at a late stage of HIV infection (see footnote 3) in England is 42% of all new diagnoses. Those with a late diagnosis in the UK in 2020 were 17 times more likely to die within a year of their diagnosis, compared to those who were diagnosed promptly. The figure for those diagnosed in England being 24, although this is substantially higher than the previous year and may include some impact of COVID-19. For HCV, the infection persists for many years without causing symptoms and so delayed diagnosis is common, although less common now in England than in other countries due to the HCV Elimination programme’s extensive number of case finding initiatives. The number of late diagnoses, defined as those commencing treatment when cirrhosis has already developed, was around 23% in 2020 (see footnote 4). This could possibly be higher among those diagnosed through active case finding among those who have been living with undiagnosed HCV for a long time and do not have active ongoing risk factors which may have triggered testing through drug and alcohol services for example.

A late diagnosis is possibly higher among those who do not have active ongoing risk factors such as drug and alcohol dependency.

Provided people are diagnosed promptly, people with HIV can expect to have a near normal life expectancy. Effective HIV treatment means those with an undetectable viral load cannot pass on the infection through sex. HBV is a vaccine preventable disease. Around 10% of people who are exposed in adulthood will develop a chronic infection. It can be acquired silently without symptoms, particularly in infancy and childhood, less frequently in adulthood. Therefore, testing programmes are often the only way of finding people living with HBV who will benefit from treatment. These people benefit from being seen by hepatology every 6 months for monitoring in case of progressive damage to the liver, the need for starting treatment to suppress the virus, or development of liver cancer. HBV cannot be cleared or cured at present. Treatment while not curative, currently aims to stop liver disease progression and these treatments are cost effective (NICE Technology appraisals). Functional cure therapies are in the pipeline.

4.4 The cost effectiveness of identifying people living with BBV and linking them to care

As well as being better for patients and the public, ED BBV testing as a case finding approach is likely to be cost effective (see footnote 5). It avoids NHS costs linked to both future transmission and the use of intensive care through late diagnosis.

For HIV, the average projected costs of lifetime HIV health care for an individual are between £100k -180k from a 2015 study. At its simplest, if each person newly identified as having HIV accesses care and treatment which prevents them passing it on to another person, the NHS saves at least the £100k it costs to care for a newly diagnosed person. It could be that the rate is less than 100% for someone to transmit HIV to another; further research is needed to understand the current situation, including the impact of pre-exposure prophylactic drugs (PrEP). For HCV and HBV, a recent study showed that ED testing was highly cost-effective, with HCV and HBV testing costing £8,019 and £9,858 per quality adjusted life year gained respectively (see footnote 3).

4.5 Health inequalities

Despite great progress towards the government’s goals for HIV, HBV and HCV, significant inequalities exist in the UK’s response to these infections. Opt out testing in EDs is an important mechanism to tackle these health inequalities as it provides an inclusive approach to testing and tackling stigma associated with both HIV and viral hepatitis.

Levels of HIV transmission are disproportionately higher in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men and people from a Black African background (see footnote 3). The proportion of Black African heterosexual and bisexual women and heterosexual men with a late HIV diagnosis in 2020 was 59% compared to 51% of white people exposed by heterosexual sexual contact. Both HCV and HBV predominantly affect socially disadvantaged and/or marginalised groups, including those who inject drugs, those experiencing homelessness and those who have close links to high prevalence countries (see footnote 4). One study found that those identified as BBV positive through ED testing are more likely to be male, Black British/ Black other ethnicity and have no fixed address .

4.6 Why opt out testing in EDs is important

There is consensus that opt out BBV testing is important within high and very high areas of HIV prevalence, and although NICE and BHIVA/BASHH guidelines state that in very high areas all should be tested, rather than just those have venepuncture , this is a pragmatic first step approach. Opt out testing in EDs is effective in identifying people who did not previously know they had a BBV and those who are no longer in regular care. Opt out testing is inclusive and offers a way to address health inequalities amongst those who would not otherwise seek out testing or be offered it in primary care or sexual health services. Opt in testing strategies may miss people who are unaware of their risk and those who may be affected by the stigma associated with risk-based testing. Evidence indicates, for instance, that Black women visiting sexual health clinics are more likely not to be offered a HIV test by staff, or if offered, to decline an HIV test (see footnote 3).

4.7 Rationale for expansion of ED testing pan-London

London leads the world in clinical outcomes for people living with HIV with 95% of people living with HIV knowing their status, 95% of those accessing care are on treatment and 95% of those with a viral load result have a suppressed viral load. London aims to be the first city in the world to end transmission of new cases of HIV.

As a key member of the Fast Track City initiative, London has taken a pan-London approach to increasing the health outcomes for people living with HIV, as described in the report ‘Evolving the care of people with HIV in London’. There have been huge achievements in HIV prevention diagnosis and treatment thanks to the NHS clinicians, local authorities, Greater London Authority, public health and voluntary sector expertise and partnerships. Funding was granted for very high prevalence (those with a HIV prevalence of more than 5 per 1,000) sites only, but a London decision was made to work with ICSs to stretch the funding to roll out to every ED site. This ensured equity of access to services across the capital and established what the reactive test rate was across lower levels of prevalence to assess effectiveness for a wider roll out nationally or internationally in the future.

5. Project aims, objectives, and key delivery priorities

This project aims to deliver a combined BBV opt out testing in EDs approach in the areas of highest diagnosed HIV prevalence. The project will encompass all aspects of the planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of this initiative.

The project’s objectives are to:

- Support integrated care systems (ICSs) in their collaborative system working to implement ED BBV opt out testing in partnership with HCV ODNs, specialist clinics, community and peer support organisations, IT, pathology, diagnostics, ED, virology, and public health.

- Use an inclusive population health approach to reduce health inequalities and increase health and wellbeing outcomes for all people living with a BBV, including culturally appropriate community services and peer support.

- Build on the experience and learning of successful sites and extensive literature and share learning and models of good practice.

- Evaluate the impact of ED BBV testing through qualitative implementation science analysis, public health evaluation, and cost effectiveness analysis and collaborate with UKHSA to explore how the combination of site level monthly data reporting and national surveillance data can enhance understanding of the project’s short and longer term impact.

- Maximise effective use of resources through exploring opportunities for pathway redesign and economies of scale.

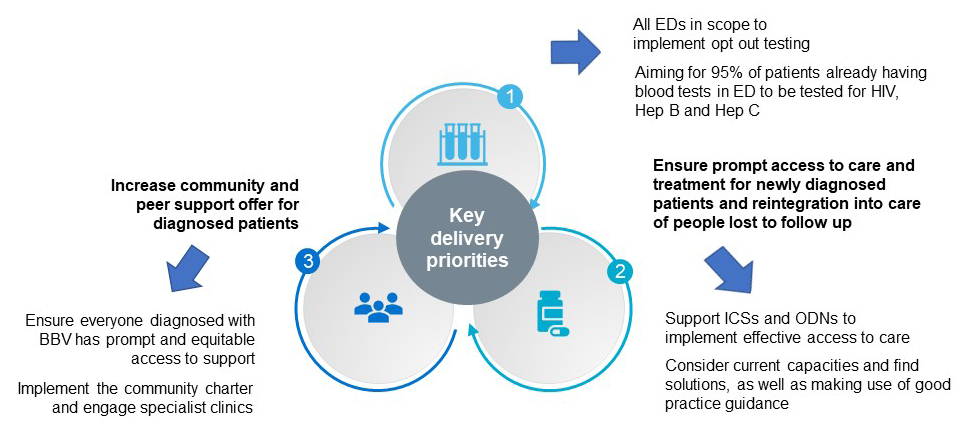

The following key delivery priorities for the project are shown in the diagram below:

- Increase implementation and uptake of testing in areas of highest diagnosed HIV prevalence

- All EDs in scope to implement opt out testing

- Aiming for 95% of patients already having blood tests in ED to be tested for HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C

- Ensure prompt access to care and treatment for newly diagnosed patients and reintegration into care for people lost to follow up

- Support ICSs and ODNs to implement effective access to care

- Consider current capacities and find solutions, as well as making use of good practice guidance

- Increase community and peer support offer for diagnosed patients

- Ensure everyone diagnosed with BBV has prompt and equitable access to support

- Implement the community charter and engage specialist clinics

6. Preparing for project launch

6.1 Building on previous learning

Opt out testing in EDs was already taking place in some areas of highest prevalence of HIV as shown earlier in Table 1. As to be expected, there was variation in the delivery, uptake and funding at each site, with site specific protocols and no mechanisms for regional coordination, oversight or targets. A key element of this project is to build on the learning from these pioneer sites and develop a robust and standardised approach to roll out BBV ED testing across all very high prevalence areas. Coordination and accountability at the system level was felt to be fundamental to this project and the newly formed ICSs were tasked to lead on the delivery.

6.2 Developing structure, governance and the ED testing good practice guidance

Following publication of the HIV Action Plan in December 2021, NHS England moved quickly to convene and engage with key stakeholders. Leaders from HIV / ED / Community / HBV / HCV sectors welcomed the initiative, recognising that concerted collaboration across sectors would be required to achieve it.

The first step was to develop a clear governance structure, including forming an inclusive and representative steering group at National and London level. The HIV government adviser is the senior responsible owner for the HIV Action Plan implementation, the Director of the NHS Prevention Programme at NHS England leads the National opt out testing steering group, and the Director of Commissioning, Specialised Commissioning NHS England – London, leads the London opt out testing steering group. Both groups are informed by the head of the HCV programme. A project team was set up including leads from Fast Track City Initiative (London), NHS England Business intelligence (London), NHS England Pathology and HIV (London), NHS England HCV Elimination team. A new role, Project Manager for ED HIV testing, was recruited.

The project set financial allocations for each ICS to support ED opt out testing. This was developed with the benefit of modelling based on ED attendance (2019 ED attendance data) and the proportion of attendees who had blood tests.

Building on strong engagement from clinicians, community organisations, ICSs and UKHSA, NHS England worked with these partners and stakeholders to agree new ways of working and to develop programme documentation to roll-out this initiative. A consultation for the BBV Opt out Testing Best Practice Guidance set out expectations for ICSs and trusts to deliver the programme. The main elements included:

- defining the BBV test bundle profile

- setting standards for testing

- communication with patients

- the opt out process

- results management

- governance

- data collection

This document built on the learning from pioneer sites and NICE, BHIVA and BASHH, RCEM guidance. It was published on the 1 April 2022 and defined the patient pathway for BBV opt out testing in EDs.

All adults attending ED who are having blood tests as part of their visit have BBV tests added unless they opted out. The good practice guidance says anyone who had had an HIV test within the previous 12 months should not be tested again in the ED. Local trusts are allowed to vary that period based upon an understanding of their local population; any test can be ordered by a clinician if clinically indicated. Non-negative results including patient notification and links to care are managed by specialist services in HIV or sexual health. Viral hepatitis results go through agreed collaboration around results management and governance.

Specialist services rapidly link patients to clinical care and community support. The specialist services for viral hepatitis are made up of operational delivery networks (ODNs) commissioned by the HCV Elimination programme. Close working with IT and pathology was developed, which allowed robust failsafe reporting for results management and some trusts to automate algorithms to ensure maximum BBV test uptake. Plans are in place to ensure EDs receive regular feedback on test uptake and the number of positive cases identified.

NHS England engaged with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and academic partners to plan for a comprehensive data, monitoring and evaluation framework to support the project. UKHSA devised a data subgroup to develop this framework in collaboration with business intelligence leads from NHS England, lead clinicians, community and HCV Elimination partners.

6.3 Engaging the community sector

NHS England – London, recognising the fundamental role that community sector organisations hold in all aspects of supporting people living with BBVs and the importance of co-producing this initiative with the community, brought together community partners in a community forum. An important piece of work by the forum was the community charter, which sets out the expectations of the forum for the holistic approach to this initiative and is intended to hold the initiative to account as it is rolled-out.

6.4 Partnership with HCV Elimination programme

A critical preparation step was engaging with NHS England’s HCV Elimination programme as a key partner to expand the scope from HIV to include HBV and HCV testing. There were three important aspects to this partnership. The first was the commitment to the roll out of HIV, HBV and HCV testing across sites as a combined BBV testing package. The second, a commitment from the HCV Elimination programme to fund viral hepatitis testing alongside the HIV Action Plan funding for HIV testing. Thirdly, the commitment to implement reflex ribonucleic acid (RNA) testing on all HCV antibody positive samples. This is important as it allows resources to be focused on those with active/untreated infection. An immediate RNA test on any positive antibody sample avoids the need for the patient to return for a second blood test, and avoids clinical time being spent on finding patients who may not be viraemic.

Once the BBV test profile had been defined in the good practice guidance, work started at pace to prepare laboratories to transition to the new diagnostic workflows needed to support this. In London, the regional pathology team started engagement with pathology networks to support the transition to the new BBV profile and to work with the networks to drive forward implementation of testing and reporting. Previously, testing was requested on an ad hoc basis and subject to the local contracted arrangements and testing protocols. The BBV test profile would test in a common way to reduce unwarranted variation.

Table 2: Timeline

| Month | Action |

| Dec 2021 |

|

| Jan 2022 |

|

| Feb 2022 |

|

| March 2022 |

|

7. Achievements in the first 100 days

New defined as new to that clinic and person not disclosing that they are under care elsewhere.

All results subject to validation with UK Health Security Agency.

Read an explanation of figure 1.

7.1 Rapid mobilisation

A particular feature of this work has been that in the relatively short space of time from publication of the HIV Action Plan the new initiative has been rolled out across multiple provider organisations in different parts of the country.

At a national and strategic level, with the help of partners in our regions and ICSs, NHS England has managed to build on the commitment in the HIV Action Plan to support opt out testing in EDs for HIV to include opt out testing for HCV and HBV. This has been achieved through effective collaboration, joint working, and alignment of linked priorities.

The successes relating to practical roll out of this project on the ground can be attributed to the multiple sectors involved and invested in its outcome. NHS staff and organisations, strategic governmental groups, charities, social care organisations, community healthcare providers, and national advisory groups have worked together to a common goal.

To aid ICSs in rapid mobilisation the project team, in partnership with stakeholders, developed standardised communication materials which they made available to all trusts. Materials were translated into several languages, such as the public information poster below which promoted the testing initiative and provided people with a route to more information about opting out.

The project has successfully built on ground-breaking work by pioneer sites. It has embraced new ways of working, with a dynamic “no regrets/learn as we go” approach to implementation. Unprecedented learning has been gained from the innovation and collaboration which took place during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Opt out testing is the key to discovering the vast majority of undetected cases of HIV and viral hepatitis within England and potentially elsewhere. It is clear that it represents excellent value for money and will enable treatment options and wider help to be provided to those who are picked up through the programme. The programme builds on forty years of clinical and community expertise which has been working together to end blood borne viruses as a public health threat.

What has been particularly heartening is the enthusiasm with which we have been able to achieve this roll out across multiple sites even within the context of very busy emergency departments.

The good that the opt out testing model does in potentially changing the lives of people living with these conditions is something taken to heart by all the clinicians and managers involved. It has been a huge privilege to be able to work with everyone on this programme.”

Ian Jackson, Director of Commissioning, London Specialised Commissioning Directorate, NHS England

7.2 Expansion of number of sites implementing BBV testing

Within the first 100 Days, 28 out of the 34 EDs in scope for this project (located in Blackpool, Manchester, London and Sussex) were operational and testing for HIV, 10 out of 34 sites for HBV and 10 out of 34 for HCV. Since that point more have started testing, with plans for the majority to be testing by the end of November for all BBVs. This compares with the position at 1 April 2022 of 20/34 EDs testing for HIV, 2/34 sites for HBV and 6/34 for HCV. Some of these were not operating an opt out process.

In the first 100 days we have developed a standardised data collection template which has been rolled out, then revised in the light of feedback. Much of this data is being collated together for the first time and has required changes in processes to be able to report at trust level, some of which are ongoing. For these reasons the following results should be thought of as indicative, whilst we work with ICSs and trusts to consolidate their reporting processes.

7.3 Testing volumes achieved

From current information reported by ICSs in the sites participating in the project, between 1 April and 30 June 2022 over 439,000 attendees had a blood test in an ED. Of those, over 250,000 received an HIV test, 78,000 an HBV surface antigen test, and 105,000 an HCV antibody test. 960 received an HCV RNA test following a positive HCV antibody test.

There are still some data reporting requirements to work through and we are working to secure robust data for the numbers of ED attendances having blood tests at each site. We are working towards a target of 95% uptake everywhere as an objective in the next phase.

7.4 Identification of people with a BBV and subsequent links to care

From the testing undertaken across all sites between 1 April and 31 July 2022 it was reported that:

- 128 people have been newly identified with HIV, and a further 65 were found who had disengaged from care.

- Of those identified to be living with HIV and not in care, 136 were reported linked to care by 31 July, of whom 110 were newly diagnosed and 26 had previously disengaged from care.

- 325 people have been newly identified with HBV, and a further 25 found who had disengaged from care.

- Of those identified to be living with HBV and not in care, 166 were reported linked to care by 31 July.

- 153 people have been newly identified with chronic HCV, 25 people found who had disengaged from care, and 7 people identified who had previously cleared the virus.

- Of those identified to be living with HCV and not in care, 119 were reported linked to care by 31 July, of whom 96 were newly diagnosed, 20 had disengaged from care, and 3 who had previously cleared the virus.

All results are subject to validation by UKHSA. Definitions are described in the next section.

7.5 Definitions

- Newly identified is defined as those not known to the clinic and who have not disclosed that they are under care anywhere else after meeting with a clinician.

- A link to HIV care is defined as attending the first HIV clinical appointment following a confirmed HIV result.

- A link to HBV care is defined as attending for their first hepatology clinic appointment following a positive Hep B sAg result.

- A link to HCV care who complied with initial clinical contact following a positive Hep C RNA result.

Links to care may take some time, and although they should occur within two weeks for HIV, this is dependent on the person living with HIV attending within that time.

Data are provisional and not yet verified by looking for previous diagnosis in national surveillance or linked to national HIV AIDS reporting system. UKHSA plan to carry out links to national datasets for testing, diagnosis and treatment and care to validate these data; this will form part of the routine monitoring undertaken by UKHSA.

“ED opt out testing has very quickly become the source of the majority of new HIV and hepatitis C diagnoses in Manchester in 2022, detecting more cases than any other testing method. It is a crucial step towards preventing new transmissions of HIV and hepatitis C to enable us to achieve getting to zero transmissions for both infections.”

Orla McQuillan, Consultant Genitourinary Medicine, Manchester Royal Infirmary and Wythenshawe Hospital

UKHSA is able to analyse data from sentinel, a clinical IT system, for blood borne virus testing, which collects BBV tests from participating laboratories regardless of result. Through linking this data to hospital episode statistics, it is possible to learn more about the demographics of people having blood tests at ED and those who additionally have a BBV test, comparing demographics with those who have not had a BBV test but have been seen in ED. This is dependent on their NHS number being recorded in the sentinel reporting system and so these data should be seen as a subset of the group. Links to surveillance data will also aid with understanding populations, the predominate risk, whether groups are missed, and who the individuals are who have never been diagnosed.

7.6 Changes to pathology processes

Ensuring the remaining laboratories, which o had not yet implemented reflex RNA testing for HCV within the target ICSs, went on to implement reflex testing was an important achievement. Routinely RNA testing positive results means that there is much less chance that we will lose people from the pathway who may be reluctant to return for a separate RNA test. Establishing a new profile, that is the combination of those tests that are required for this purpose, has also been a significant step forward, as has been the adoption of the profile by laboratories serving EDs within the project.

7.7 Increasing community support

Culturally appropriate community services and peer support is critical if we are to improve people’s health and wellbeing outcomes and avoid losing people in either their linkage to care or ongoing treatment. Support provided by people living with HIV, for people living with HIV, is a key component of good patient-centred HIV care. This provides specialist support and connects people living with HIV to share experiences and build resilience and helps to ensure continued engagement in care. Of those who used HIV support services, 92% said they had been important to their health and wellbeing (Positive Voices, 2017).

George House Trust

As testing for HIV in EDs was being established, George House Trust met with Manchester Foundation Trust to ensure appropriate referral pathways to community based social support for people diagnosed with HIV. It was agreed that anyone receiving an HIV diagnosis because of ED HIV testing would be offered a referral to George House Trust and be sent a link, via text message, to a page on the George House Trust website with information about HIV.

Case study

- Gay man, aged 33. He reports that he regularly attends sexual health services for routine screenings.

- A representative from Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust telephones him after he attended ED and was tested for HIV. The man was asked to attend Withington Community Hospital the following Monday for further tests. Details of his suspected diagnosis were not given over the phone.

- He received his HIV diagnosis and was referred to George House Trust.

- He was contacted by George House Trust to arrange a one to one appointment

- He was seen by an adviser from George House Trust Services and subsequently received one-to-one support. He reported that the support was helpful for bringing his HIV knowledge up to date. He also stated that he didn’t remember much of what he was told at his first clinic appointment.

- He has told close friends and family and reports that they are supportive.

- He has been referred on for peer mentoring at George House Trust and is currently waiting to be matched with a volunteer mentor.

Provision of community services and peer support is patchy due to a lack of funding. There is a significant opportunity for ICSs to show leadership within new NHS structures. Effective system leadership can draw together providers, commissioners and those people most affected by HIV as partners to ensure there is funded support for people newly diagnosed or already living with HIV.

The HCV Elimination programme has peer support at its core. This is primarily provided nationally through the Hepatitis C Trust, commissioned by NHS England. The programme provides:

- peer support

- HCV awareness training

- outreach testing and treatment

- opportunities for volunteering

- employment for peer workers.

Studies have shown the importance of peer support. Participants approached through outreach services were two-and-a-half times more likely to engage with healthcare systems if they were in a peer support group, and a 12% increase in those starting HCV treatment if they had contact with a peer. Nurse-led support to help people navigate the system is also important, based on evidence such as the EMPACT-B study for HBV, and needs to be embedded within the pathway.

Community organisation peer support as part of the care pathway

“We are lucky at the North Middlesex to have embedded peer workers from the community organisation Embrace UK who work with patients struggling with stigma and psychosocial difficulties. We have had opt out HIV testing in our emergency department since 2020 and the input of our peer mentors has been invaluable. A woman in her 50s who was recently diagnosed through this initiative was referred to a peer mentor as an inpatient. She had very little knowledge of HIV, was afraid that she was going to die and was terrified of disclosure. She also had precarious housing and financial insecurity. She felt more positive after just her first meeting with the peer mentor who had educated her about HIV. The patient stated that she was reassured by the fact that she would never have known the mentor was living with HIV if she had not disclosed this. This clear demonstration of health in someone living with HIV was transformative. The mentor has also helped the patient navigate her financial situation. Peer mentoring has enhanced this woman’s quality of life and contributed to her excellent engagement in care”.

Hannah Alexander, HIV Consultant, North Middlesex Hospital

“Embrace UK provides people with socio-emotional support, reliable information about HIV, adherence support, and referrals to other organisations. Holistic and client centred approaches are our core practices to improve the well-being of service users.”

Mesfin Ali, Health Services Manager for Embrace UK

Community and peer support capacity will need to increase due to the number of new HIV, HBV, HCV diagnoses found through this project. To help achieve this, NHS England London region has recommended that 10% of the funding made available to the ICSs to support HIV testing should be used to commission additional community sector input.

Historically, linking people found to have HCV or HBV to care has been less successful than linking people with HIV (see footnote 6) to care. The ‘Going Viral’ programme in nine UK EDs engaged and retained all patients diagnosed with HIV in care. Whereas for HCV and HBV the proportion newly diagnosed and linked to care was 36% and 60% respectively, with only 20% of those previously diagnosed retained in care (see footnote 7). This may reflect differences in standard processes for linkage. However, this is a critical step in the care cascade and a variety of approaches are likely to be needed. As well as peer support programmes, collaboration with services aimed at supporting key populations, such as the London Find and Treat service, have been developed to allow those found to be positive for a BBV through ED testing to be offered care.

We have engaged with the community sector to draw up a set of principles, called “a community charter”. We will propose to each ICS that they use the charter to help inform their commissioning of BBV testing.

Drafting a community charter

- Comprehensive community support provision should be made as early as possible for those positively diagnosed with a blood borne virus through opt out ED testing.

- Transparency is needed on the funding and commissioning of community support as well as accountability of its appropriateness and effectiveness in supporting people and keeping them engaged in care and treatment.

- Community support should be mapped across London. Opportunities to commission within and across boroughs and ICS boundaries should be explored and communicated to community partners.

- The long term cost benefits of financing community organisations to support engagement in care should be captured and highlighted in the monitoring and evaluation of the programme.

- Where disengagement is prevalent, there should be openness to form effective strategies for reengagement and an understanding that a holistic, community and person-centred approach may need additional funding.

Table 3: Timeline of the first 100 days

| Month | Action |

| April 2022 |

|

| May 2022 |

|

| June 2022 |

|

| July 2022 |

|

8. Learning from the first 100 days

In this section we reached out to our stakeholders and partners and asked them to share their reflections on the first 100 days with us.

8.1 Patient views

Firstly, we spoke to three patients newly diagnosed with HIV through ED testing and asked them what they thought about opt out testing in EDs:

“It is the right thing to do. I know you can get tested in a sexual health clinic, but I don’t want to go there. The clinic is right off the main road and everyone can see you going in there and I know they will be talking.

“You wouldn’t ever think you could have it; I’m not promiscuous, I was only with one person for the last 10 years. It isn’t like herpes or a rash which is on one bit of your body, that you would go to a clinic for: it is a viral thing, it is in your whole body.

“If you do it like this in A&E, you will get a whole lot more people. If you give the test to everyone you take away people’s view of it being a dirty disease. It isn’t difficult to have a conversation about cancer- “oh you have a cough for a while, better get a check to make sure it isn’t cancer” – it should be like that for this too, but it isn’t because of the stigma, it is hard to have the conversation and people don’t know there is treatment so they wouldn’t go for a test.

“This is for people who are unaware. It is ignorance and I was one of them. Back in the day when it first came around, it was such a big thing. I remember it, it was awful. I watched “It’s a Sin” recently. I couldn’t watch it when I was first diagnosed, it was too much but I watched it now and it is amazing.

“Before I was diagnosed, I didn’t know there was treatment. Before this, I would never have had a test because I thought there was nothing that could be done

“I would much rather have been told sooner that I had it and that there was treatment that could give me the rest of my life back. I’d rather be told that I have HIV than be told I have cancer, could have been a lot worse. At least this means I will see my kids grow up.”

Ann (not her real name), a white British woman in her 50s

“When I felt unwell and went to the emergency department, it was a life saver – I got diagnosed with HIV and I wouldn’t have known otherwise. The opportunity to be tested meant that I got treatment and was able to carry on with my life. For me it was a really positive experience.

“I think testing in A&E is a very proactive thing to do because having the opportunity to have the investigation could potentially save your life, I think it is something that should be offered to everyone. I don’t see any downside at all. Everyone should have the opportunity. It makes you aware and that it can save your life instead of not knowing. HIV is still taboo for many people and they don’t know about treatment. There is still stigma.

“My view is people need to get more information about HIV, especially about the treatment. Everyone should be aware that HIV testing is being done in A&Es.”

PS, a man in his 40s.

“I attended A&E for a completely unrelated reason. I did not see the posters in the waiting room about HIV testing or I feel I may have opted out. I was initially angry about being tested as I felt I had control taken away from me, but after being diagnosed and speaking with the doctors and learning HIV is just a long term manageable condition and with treatment it does not reduce life expectancy, I now feel very grateful I have been diagnosed as I don’t think it’s something I would have been tested for in the near future.

“Don’t die of ignorance” get tested and take control of your health and to help erase the stigma of HIV”.

Newly diagnosed patient, Male, aged 50

Both PS and Ann reflected on the stigma that still surrounds HIV and the lack of knowledge for many people around the advances in treatment that means people diagnosed now with HIV can live long healthy lives with treatment. This is similar for those living with HCV, as shown below.

“When I called a patient recently to communicate to her the positive hepatitis C result, she told me that she had known she had the infection for many years but had been burying her head in the sand. She is now on treatment with excellent chances of cure and she feels very positive about that”.

Debbie Kennedy, Infectious Diseases Specialist Nurse, Wythenshawe Hospital

8.2 Implementation is complex and subject to multiple factors which both support and impede roll-out

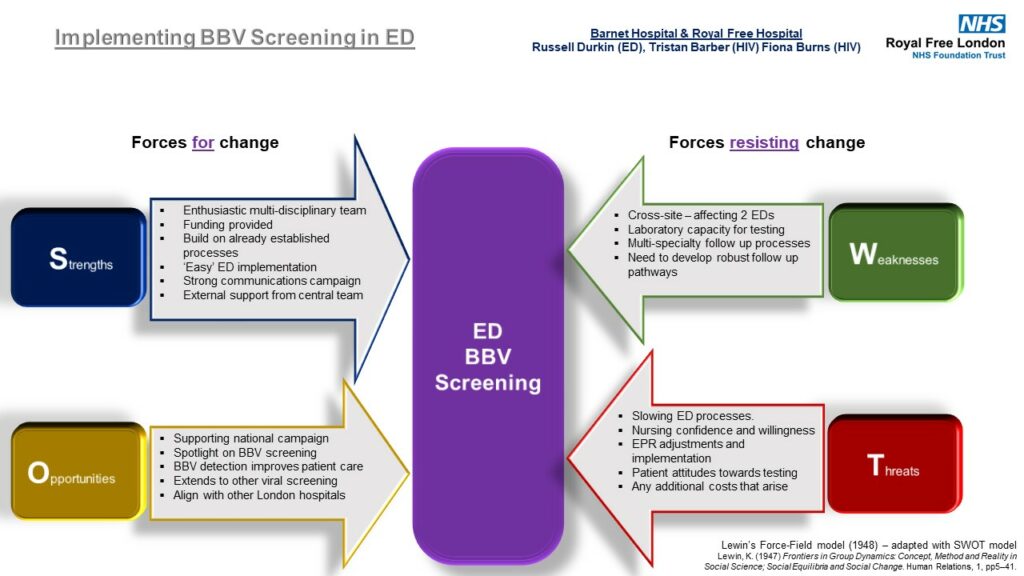

Dr Russell Durkin, ED Consultant at the Royal Free Hospital and Barnet Hospital, led the implementation of opt out testing in Barnet and Royal Free in April 2022. He shared the diagram below (figure 5) which illustrates some of the challenges and enablers in the implementation of testing in his trust.

Dr Durkin’s SWOT analysis diagram shows the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the opt out screening initiative in emergency departments.

Strengths

- Enthusiastic multi-disciplinary team

- Funding provided

Weaknesses

- Cross-site – affecting 2 EDs

- Laboratory capacity for testing

We found Dr Durkin’s analysis to be mirrored in many other sites. Enablers reported by sites include

- dedicated funding,

- experience in the trust of successful opt out testing pilots, such as:

- the Elton John AIDS Foundation Social Impact Bond ‘Zero HIV’ programme which supported HIV testing work at Kings College Hospital and University Hospital Lewisham, as well as primary care and community testing

- The nine hospitals that participated in the 2014 “Going Viral” campaign

- previous ED HIV testing work such as in Guys and St Thomas’ Trust, the Royal Free Hospital, St Barts, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and Manchester Royal Infirmary

- strong clinical leadership from ED consultants,

- good support from NHS England including standardised patient facing communications material and guidance for implementation.

Challenges to implementation include:

- laboratory and clinical capacity

- costs, introducing new diagnostic profiles and workflows

- the need for robust multi-speciality pathways for results management.

8.3 The importance of system leadership

Preparation for roll-out progressed rapidly. The project could not have progressed at that pace, in those first 100 days, without the devotion and perseverance of ICSs in bringing together local clinicians and community organisations to lead implementation in their areas. The rapid mobilisation went very well, even at a time when the ICSs were being formed, with each ICS having different levels of experience, capacity, and engagement. NHS England supported the ICS leads by defining clear expectations for ICSs, aligning recommendations with existing policies and setting timelines wherever possible. Early engagement with the ICSs including identification of ICS leads for delivery of the programme and delivery plans to ensure sufficient diagnostic support and treatment capacity, were in place at the beginning of the 100 days to meet the needs of expanded testing.

“It has been a fantastic privilege to partner in a programme that has invoked such enthusiastic and integrated engagement across health and social care and third sector organisations.

From involving those with ‘lived experience’ to delivering improved health outcomes and addressing health inequalities, this project is a consistent conveyor of good news.

It is thanks to hard working ED staff and those supporting them with the testing that we’ve managed to perform a high volume of tests since launch in April, not only identifying those with HIV but reconnecting us with those who had previously tested positive and lost contact with local services.”

Lola Banjoko, Executive Managing Director, Brighton and Hove, NHS Sussex

8.4 Recognising and responding to impacts on capacity

Pathology capacity

This initiative involves initial screening tests for HIV, HBV and HCV for all patients attending ED and who have blood tests as part of their routine care. This is a significant volume of additional tests for pathology networks to absorb. In London, the Pathology Programme Team regularly meets with all the London pathology networks to support implementation, however capacity was strained in some locations while baseline requirements were determined. The Pathology Programme team monitors any changes in project activity that may impact capacity, where this does happen there will be local discussions about support and mutual aid.

Clinical capacity

Early data shows significantly higher numbers of HBV cases than forecast. This is placing a strain on local hepatology departments managing any new cases identified in ED. Work is being led by the HCV ODNs, primarily within existing resources., Each ICS must rapidly scale up networked pathways and establish new ways of working to ensure that all patients who are newly diagnosed with HBV are rapidly linked into care. This has included creating new roles and strengthening medical capacity in non-specialist centres. The development of these pathways is critical to provide a timely and robust results management pathway and ensure no undue delays in the roll-out of viral hepatitis testing.

“The numbers of new HBsAg+ and HCV RNA+ patients (new or lost to follow-up) identified through ED screening have been much higher than expected (greater than 35 per month and three-fold higher than a 2015 pilot of ED screening at the RFH site). This may represent a fall in detection/screening in primary care in the last 7 years. The majority of cases are hepatitis B. This increased caseload of greater than 35 additional new patients a month is having a significant impact on our viral hepatitis service in which consultants typically already have greater than 20 patients in a clinic. Waiting lists were long prior to launch due to the COVID backlog. We have changed the pathway for new patients so they see a CNS in the first instance in a one-stop and then enter the HCV treatment pathway directly or await next available consultant review for HBV or HCV (unless there are urgent issues). This is keeping waiting times to less than 4 weeks for first assessment for now but this is rapidly lengthening, and we will need to expand both viral hepatitis CNS and consultant capacity.”

Doug Macdonald, HCV ODN Lead for North Central London, Royal Free Hospital

8.5 New ways of working are needed

Implementation of this initiative required new clinical, IT and pathology pathways to be developed. This requires a high degree of collaborative working at the system and trust level and there is no “one size fits all” solution for each trust. The project team support ICS leads to undertake the detailed and often time-consuming operational conversations required at each site in the initial stages of implementation. Successes and challenges are shared between all ICS to ensure everyone can benefit from the learning.

“A fundamental part of this initiative was the establishment of the pathology testing profile for the BBV test bundle (HIV, HBV and HCV). The BBV test bundle includes; screening, confirmatory (HIV only) and disease profiling tests (HCV only), enhanced testing is not included for every disease because of the overall programme budget and subsequent disease management requirements. In the London region there are 5 pathology networks in place, all have established local processes, procedures and equipment for testing and this has made implementation more challenging, because of the need to adapt localised arrangements. The BBV testing requirement is also provided in accordance with the laboratory United Kingdom Accreditation Service for operational governance reasons. The London Pathology Programme has worked (and continues to do so) with all the networks to establish and operationalise the BBV testing programme.”

Adam Cooper, Pathology Lead, NHS England London region

“The program highlighted weaknesses and risks in our internal notification systems of new cases. Email notifications of authorised new positive results works well for small volumes of cases however with >35 new cases of hepatitis B and C identified per month by ED testing, this quickly became unworkable and unauditable. To address this, we introduced a single-point SharePoint notification form in collaboration with microbiology and virology at RFH and BH sites. This standardises the minimal information needed (eg site of blood test, result, patient identifier) and uses drop-down lists/default values to ensure it is as quick as sending an email. The SharePoint list automatically updates a clinic management tool (MS Access) which then organises the patient engagement and booking process between a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and coordinator into a series of sequential worklists. Emails are no longer required.”

Dr Douglas Macdonald, HCV ODN Lead for North Central London, Royal Free Hospital

Embedding routine BBV testing in busy EDs is challenging but can be done

Although several trusts in England had established ED opt out testing projects, a large number went live for the first time or significantly scaled up their testing in April 2022. In the context of unprecedented strain on EDs following the Covid pandemic, this is an enormous achievement and is testament to the clinical leadership, dedication, and innovation of ED clinicians who drove this forward in their departments and learned from their journey.

Communicating successes is key to maintaining the enthusiasm and motivation of ED staff. Feeding back the number of newly identified and lost to follow up patients found either verbally by clinic staff or in newsletters is very helpful and welcomed.

Case Study: St Helier and Epsom

St Helier Hospital has been offering opt-out HIV testing in its emergency department (ED) since November 2019. This was originally thanks to a two-year pilot funded by ViiV, a pharmaceutical company. The level of uptake of HIV testing in the ED has varied over the years, affected by pauses in the programme during waves of Covid and blood bottle shortages. In April 2022, 346 HIV tests were done in ED.

Dr Olubanke Davies, Consultant GUM/HIV, has been working with the ED team to address the inconsistent level of uptake. Emergency Medicine Consultant and newly appointed Clinical Lead Dr Jameel Karim adopted the following approach with great success:

- A doctor in training (Dr Emily Tridimas) leads this as her quality improvement project with passion and determination, supported by a health care assistant (Jamson Joseph) as an HIV testing champion.

- Addressing questions at handovers, which was important to allay fears especially around consent and positive results.

- Bundling of tubes with red rubber bands was a good visual way of reminding everyone why we are doing it (this took several hours a week to do). Helped to change habits by breaking the cue, habit and reward cycle.

- Sharing successes with the nursing teams initially in person and then in emails

- Addressing naysayers early, directly and publicly and empowering the group to challenge them.

- Good visual communications especially posters and PowerPoints summarising the rationale for testing.

- Creating a little competition with St Helier and Epsom EDs.

In June 2022, 2,359 HIV tests were done in St Helier ED, an increase of over 2,000 tests compared to April 2022. This is an uptake of 97% of patients who had bloods taken in ED. Of these tests, one new patient was newly diagnosed with HIV, one patient was re-engaged, and three patients were known to have HIV and were already engaged in care.

Epsom Hospital launched ED HIV testing in mid-May. Of 1,845 patients who had blood tests in ED in June, and who had not had an HIV test in ED in the preceding three months, 1,489 had an HIV test. This represents an uptake of 81% for the first full month of HIV testing in ED.o9

Such a high level of testing from the start is unprecedented and is testament to the hard work of staff in launching testing successfully. Dr Olubanke Davies worked with Dr Dai Davies, Locum Consultant Emergency Medicine, Jennifer Halliday, and Dymphna Burke, Head of Nursing to ensure order sets were correctly set up, communications materials were in place and clinicians were aware of upcoming changes. Thanks to all the nursing and health care assistant staff for changing behaviours and practice and their hard work which has made this all possible.

8.7 Funding levels will require regular monitoring

Initial funding allocations to ICSs were based on forecasts from 2019 ED data. However, data suggests that 2022/23 ED attendances will be higher than this. In most ICS footprints if the initiative is successful in testing all eligible adults attending ED, there may be a funding shortfall. We are working to assess current system delivery costs and will monitor it throughout the year, with a possible further application for funds to the HCV Elimination budget. This programme will enable commissioners to determine the unmet need around HBV to inform future service delivery.

8.8 Monitoring and maximising cost effectiveness will be required

There are no published prices in pathology throughout the NHS and as contracting for the services are very local (normally by trust) it has been problematic to agree standardised prices with the pathology networks, including not being able to share pricing due to commercial sensitivity. This has given rise to some inconsistency in what has been agreed for 2022/23 but does also present an opportunity when commissioners consider the future funding arrangements.

8.9 Repeat testing is a complex issue and dependent on virus, population and prevalence

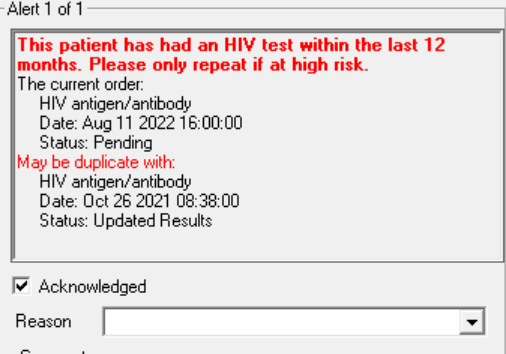

The good practice guidance recommends not testing, or ‘blocking’, anyone who has had an HIV test in ED within the previous twelve months. Clinicians in the ED can still request an HIV test for a patient where there is a clinical need to. ED 7-day re-attendance rates in England rose to 10% in 2020-21. This equates to approximately 1,400,000 patients re-presenting to an emergency department in England, within 7 days of their original attendance, per year.

Laura Hunter, ED Consultant at St Thomas’ shares below how her trust has responded to this issue.

Electronic pre-configured alerts may be used to reduce unnecessary repeat testing in repeat attenders, such as the below alert used at St Thomas.

The impact of this unnecessary testing can be seen in the below analysis undertaken by Kathryn Harrop, Project Manager, South London Specialised Services. She shows the impact of introducing blocking at Croydon University Hospital, contrasting those who have blood tests in ED compared to the number of those eligible for an HIV test (for instance those who have not had an HIV test within the last 12 months).

Table 4: Croydon University Hospital ED attendances analysis

|

Month (2022) |

Count of adult ED attendances with blood tests for any reason |

Count of ED attendances with blood tests for any reason minus those who have been blocked |

% eligible |

|

April |

6,071 |

3,981 |

66% |

|

May |

5,933 |

3,950 |

67% |

|

June |

6,084 |

3,951 |

65% |

Between April to June 2022 after blocking had been introduced, an average 66% of patients attending Croydon University Hospital ED who had a blood test were eligible to have an HIV test. At University Hospital Lewisham the average eligibility over a three-year period was 73% of those having bloods taken. This shows that sites which block repeat testing can avoid the costs of about 30% of the tests that would be otherwise be undertaken. This can represent significant cost saving for trusts, freeing of pathology time and avoid patients having multiple HIV tests over several admissions. Blocking has been introduced in 7/ 34 sites, with more planned.

8.10 Data and reporting across different sites and systems required work to get right

An interim reporting template was agreed and used across all sites. This template includes data items from multiple systems (for example laboratory information management systems (LIMS), electronic patient records (EPR, acute trust) and local clinic service systems). ICSs are responsible for the collation and submission of the data.

There have been some challenges for some systems bringing the data sources together. This is a new requirement and has necessitated different teams working together to understand the best ways of getting the data. There is a degree of manual data collection from the HIV / GUM / Hepatitis Services about patient clinical follow-ups. It is envisaged that in collaboration with UKHSA, that data collection will become more automated and embedded within national mandated reporting requirements. It is also envisaged that programme monitoring metrics that were defined and agreed in the data subgroups will be reported.

We are also gathering baseline data to understand the adoption of good practice guidance and local variations across different systems. Examples include:

- from what age people are tested

- whether ‘blocking’ is in place

- whether there is automated notification of reactive tests to clinical teams.

For age inclusion in testing, currently 18 sites use 16 as the age from when they will test and 13 sites use18. We will progress this standardisation in the next phase.

9. Looking ahead

There is much work to do to deliver our objectives by the end of the first year. Below sets out our approach:

9.1 Collaborative system working with ICBs and key stakeholders

Continue collaborative working with ICSs and ODNs to make ED opt out testing routine in the areas of highest prevalence. We aim that 100% of sites are testing for the BBVs selected for their site by the end of the year, and support sites to achieve the 95% of testing uptake target. We will:

- ensure prompt linkage to care and treatment for those identified through ED testing through all sites

- systems to have finalised patient pathways for linkage to care and treatment for each BBV (by Q3/4)

- work with UKHSA to refine patient level linkage from ED testing to retention in care

- work on understanding attrition on care pathway.

9.2 Inclusive population health approach to BBV opt out testing to prevent ill health and reduce health inequalities in underserved communities

We will work to ensure comprehensive and culturally appropriate access to community support for those identified through ED testing, and report on offer and uptake of community support for all people newly diagnosed or re-identified. We will discuss the embedding of the community charter in ICSs. There will be a focus on health inequalities in the UKHSA analysis, with continued attempts to expand coverage of sentinel surveillance of blood borne virus testing to all laboratories involved in the project including:

- the use of Sentinel data to identify what groups are being tested

- look into the possibility of identifying those who opt-out and how that population compares to those tested

- who is being linked to care and who is not

- which are the groups most affected by LTFU

- who is being offered and who accepts community support

9.3 Sharing and dissemination of good practice and learning

We will disseminate the learning and good practice from this project through sharing reports, presenting at conferences, supporting clinicians and community groups to publish papers, and publicising through communications across the various NHS channels.

The team will work alongside professional associations such as BHIVA, BASHH, British Viral Hepatitis Group (BVHG) and the British Association for the Study of the Liver (BASL), whose members are implementing ED testing to share learning. Conference opportunities such as the International Association of Providers of AIDs Care Fast Track Cities conference later this year will enable us to spread our learning to other countries striving to achieve the 2030 targets of zero transmissions.

9.4 Evaluate the impact of ED BBV testing

We will complete the discussions with UKHSA and agree the final evaluation proposal, aiming to start the evaluation in Q3/4. We will explore the opportunities for a potential NIHR application, to investigate costs avoided through identifying people living with BBV at an early stage and other areas of interest. Vital elements of this work include:

- confirmation of diagnostic status

- exploration of the positivity rates for each BBV across sites

- confirmation of linkage to care

- confirmation of reintegration into care using linkage with national surveillance datasets.

9.5 Maximise effective use of resources

We will explore efficiencies re pathology costs, including consideration of setting a London wide price for HCV reflex testing and bundled tests. We will support ICSs and ODNs in considering how they can use a network approach to support all those who need care within their areas.

We will work to transition to Web portal data reporting by the end of quarter 3 to improve data reporting quality and minimise the burden on reporting organisations.

Footnotes

Footnote 1:

Simmons R., Plunkett J., Cieply L., Ijaz S., Desai M., Mandal S., Blood-borne virus testing in emergency departments – a systematic review of seroprevalence, feasibility, acceptability and linkage to care. HIV Medicine 2022; 1-21

Parry S,. Bundle N., Ullah S., et al. Implementing routine blood-borne virus testing for HCV, HBV and HIV at a London Emergency Department – uncovering the iceberg? Epidemiol Infect. 2018 Jun;146(8):1026-1035

Evans H., Balasegaram S., Douthwaite S., et al. An innovative approach to increase viral hepatitis diagnosis and linkage to care using opt-out testing and an integrated care pathway in a London Emergency Department. PLoS ONE 2018; 13(7):e0198520

Williams J., Vickerman P., Douthwaite., et al. An economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of opt-out hepatitis B and hepatitis C testing in an emergency department setting in the United Kingdom. Value in Health2020 Aug; 23(8):1003-1011

Williams, J., Vickerman P., Smout E., et al. Universal testing for hepatitis B and hepatitis C in the Emergency Department: A cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis of two urban hospitals in the United Kingdom. Research Square [pre-print] Mar 2022: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1474090/v1

Prasad Y, Phyu K, Parker L, et alP63 ‘Get tested LeEDs’: testing for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV in an Urban emergency department via notional consent. Gut 2020;69:A37.

Footnote 2:

There has also been funding made available to a further 8 Operational Delivery Networks (ODN)s undertaking case finding in some of their EDs. This in addition to ODN funding, and the funding for the Direct Acting Antivirals, funded through the unique strategic procurement. Initial funding was for 1 year.

Footnote 3:

HIV testing, new HIV diagnoses, outcomes and quality of care for people accessing HIV services: 2021 report December 2021. UK Health Security Agency, London

Footnote 4:

Harris HE, Costella A, Mandal S, Desai M, and contributors. Hepatitis C in England, 2022: Working to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health problem. Full report. March 2022. UK Health Security Agency, London.

Footnote 5:

Prabhu VS, Farnham PG, Hutchinson AB, Soorapanth S, Heffelfinger JD, Golden MR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of HIV screening in STD clinics, emergency departments, and inpatient units: a model-based analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19936.

Williams J, Vickerman P, Douthwaite S, Nebbia G, Hunter L, Wong T, et al. An Economic Evaluation of the Cost-Effectiveness of Opt-Out Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Testing in an Emergency Department Setting in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2020;23(8):1003-11.

Footnote 6:

S. Parry, N. Bundle, S. Ullah, G. R. Foster, K. Ahmad, C. Y. W. Tong, et al. Epidemiol Infect 2018 Vol. 146 Issue 8 Pages 1026-1035 Accession Number: 29661260 DOI: 10.1017/S0950268818000870

Footnote 7:

Dhairyawan R, O’Connell R, Flanagan S, Wallis E, Orkin C. Linkage to care after routine HIV, hepatitis B & C testing in the emergency department: the ‘Going Viral’ campaign. Sex Transm Infect. 2016;92(7):557.