Introduction

The NHS is committed to reducing healthcare inequalities and delivering equitable access, excellent experiences and optimal outcomes for everybody. To achieve this, we need to understand and respond to the needs of all the communities we serve. High quality data that helps us understand who is experiencing health inequalities is critical to this.

This plan sets out targeted actions to strengthen the quality, consistency and completeness of ethnicity data recording. It supports NHS organisations to identify and act on issues that affect their ability to record and analyse ethnic health inequalities data.

The NHS Data Dictionary provides guidance on how ethnicity should be recorded (in most cases referencing 2001 Census ethnicity codes but also 2021 Census codes for some national collections) and work is underway to support the consistent adoption of modernised categories through the development of a revised information standard on ethnicity and other protected characteristics. In the meantime, new data products should use 2021 Census codes. See Annex A for interim guidance on reference data for ethnicity to support the use of modernised codes for new data products. Office for National Statistics (ONS) guidance states that ethnicity should be self-defined and recorded collaboratively and with the agreement of the patient.

Why the quality of ethnicity data matters

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed and amplified long-standing health inequalities faced by ethnic minority communities. Research has shown that ethnic minority people report poorer healthcare experiences and outcomes compared to White British people. For example, Black and Asian women experience higher rates of mortality in pregnancy and childbirth, and Black and Asian people experience poorer access to mental health services, despite higher rates of mental ill health. Some communities, such as Gypsy, Roma and Traveller, and Jewish people are not well reflected in current healthcare data, but are known to experience profound inequalities in their access to, experience of and outcomes from services. These inequalities highlight the critical need for robust, consistent and timely ethnicity data to guide targeted interventions and ensure equitable healthcare access and outcomes.

Contributing factors include a lack of accessible information about services, language barriers and mistrust of healthcare or statutory systems. This mistrust is often shaped by historic and ongoing experiences of medical injustice, lower health literacy and a lack of understanding of how to navigate services. These barriers can result in longer waits for appointments, delays in seeking care and poorer access to appropriate support, resulting in slower recovery times and long-term effects such as worse health in later life. Poor quality ethnicity data makes it harder for the NHS to understand who is being left behind and why.

Good quality data – complete, accurate, up to date and consistently recorded across systems – is essential for effective service planning, quality improvement and monitoring the equity of services.

Ethnicity data quality within NHS data sets remains variable, with the most significant data gaps and inaccuracies often found among communities already experiencing the greatest disadvantage. There are many reasons for this. Some are structural or technical – outdated systems, limited classifications or inconsistent recording practices. Others are more systemic or rooted in lived experiences, such as mistrust or concern about the collection and use of ethnicity data. At the same time, healthcare staff may not always feel confident or well-equipped to ask about ethnicity in a sensitive, respectful way.

Consequences for patients’ access to health and care services

Good quality ethnicity data is essential for appropriate risk stratification as well as the delivery of equitable and personalised care. Without complete and timely ethnicity data, the NHS cannot reliably identify inequalities in access, experience or outcomes between ethnic groups and design tailored interventions to address the barriers faced by different communities. This risks entrenching existing inequalities. Improving the safety and quality of care for all communities requires us to understand how well services currently serve those with different ethnic identities, and how they respond to the cultural, linguistic, social and economic barriers to accessing services. Without this, communities may experience services that are unresponsive to their needs, which will erode trust and engagement among those already experiencing poorer outcomes.

Consequences for service planning and delivery

Poor insight into populations can reduce the efficiency of efforts to plan and deliver services in line with population needs. It can also mean the needs of individual patients are missed, increasing the risk of patient safety incidents and missed appointments, and putting further pressure on the NHS. The results are poorer health outcomes and increased need for more costly healthcare, including hospital admissions.

Consequences for research and innovation

Incomplete data can weaken the evidence base needed to improve equity in research and health innovation. It limits the potential of new treatments, services and products to reduce health inequalities. As the NHS increasingly adopts digital and AI technologies, it is vital that data sets are representative of the populations they describe and inform effective analysis of the effect of these changes on the whole population. Incomplete data risks embedding dangerous biases in digital tools (for example, racial bias in a clinical algorithm), which can compound rather than reduce health inequalities. Poor quality data also hampers the alignment of NHS service data and population-level data provided by the ONS and others. Ethnicity recorded at death is drawn from healthcare records, so NHS ethnicity data needs to be accurate to understand ethnic inequalities in life expectancy.

However, it isn’t just about how much and how well the data is collected, but also how that data is used to improve the quality of services. In many cases, even incomplete data is sufficient to tell us that inequalities may exist in people’s access, experience and outcomes. The data gaps themselves tell us where further investigation is needed into the experiences of populations and whether care is meeting people’s needs.

Implementing this plan

Improving the quality of ethnicity data begins with a clear understanding of how ethnicity is currently recorded across your organisation’s data sets. This plan helps you to identify and interpret gaps in ethnicity data.

Recognising where variation exists is a critical first step to identify where you need to improve. The domains for improvement offer a structured framework for targeted action. However, local context is crucial and working with staff and patients is essential. Although not every action will be relevant for every organisation, these domains support a comprehensive and coordinated approach to strengthening data quality. The case studies illustrate how this has been done in practice.

National action on ethnicity data quality

In addition to the actions for ICBs and providers set out in this plan, we are also taking national action to improve data systems, support good practice, and enhance the visibility of inequalities in access, experience and outcomes across different ethnic groups.

To support improvements in the quality of ethnicity data, we will:

- improve the visibility of ethnicity data quality and ensure that more data is available with breakdowns by ethnicity, where this supports better understanding of inequalities in access, experience and outcomes

- disseminate tools and resources that help staff and patients with ethnicity recording – reducing duplication, promoting good practice, and scaling effective approaches nationally

- empower commissioners to set and uphold clearer standards and expectations on ethnicity data quality, including across private and voluntary sector providers. These standards will be embedded within service quality and performance reviews

- introduce a modernised ethnicity classification to replace outdated and unsuitable ethnicity codes and better reflect the populations the NHS serves. This will align with developments in equalities monitoring policies and legislation

The current quality of ethnicity data

Completeness and consistency of ethnicity data in routine data sets

To assess quality in routine NHS data sets, descriptive analyses of ethnicity coding were conducted in selected English NHS secondary and community care data sets. All secondary care data sets were accessed by the Strategy Unit via secure NHS platforms: the Unified Data Access Layer (UDAL) and the National Commissioning Data Repository (NCDR).

The following data sets were analysed:

- Secondary Uses Service (SUS)

- Admitted Patient Care (APC) – inpatient

- Outpatient (OP)

- Emergency Care Data Set (ECDS)

- Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS)

- Community Services Data Set (CSDS)

Completeness of ethnicity recording was explored by assessing 3 data categories (as defined by the NHS Data Dictionary):

- Z = Not Stated: individuals are asked but choose not to disclose their ethnicity

- 99 = Not Known: individuals are not asked about their ethnicity, or they are unable to answer

- Null/?: a code is not recorded or the code entered is not in the data dictionary

Data sets are stored separately within NHS systems. This means that ethnicity must be recorded separately in each, even when the same person accesses services covered by the different data sets.

Multiple records for individuals were included, so that the analysis reflected differences across records. For example, if someone had a valid ethnicity code in one record but a missing ethnic category code elsewhere, both were taken into account for this analysis.

The analyses showed the completeness of ethnicity data recording varies between care settings and between providers (Table 1). Nationally, the proportion of ethnicity data missing from records ranged between 18% and 32%. Inpatient and emergency care providers were most likely to record ethnicity and non-NHS providers providing NHS services were least likely to. Since 2020, the completeness of ethnicity data has decreased across all data sets analysed, except for the Mental Health Services Data Set which has improved since 2022/23 and community services where completeness is steady over this period (Figure 1). Any changes to an individual’s ethnic category code, reflecting changes in ethnic identity, were reflected in this analysis.

Table 1: Completeness of ethnicity recorded across data sets in 2023/24 by type of provider

| Data set | Percentage with valid ethnic group codes | ||

| NHS providers | Independent sector providers | Local authority providers | |

| Admitted Patient Care – inpatient | 86.1% | 51.8% | Not applicable |

| Emergency Care Data Set | 84.3% | 51.5% | Not applicable |

| Outpatient | 77.1% | 30.6% | Not applicable |

| Community Services Data Set | 71.6% | 51.6% | 81.5% |

| Mental Health Services Data Set | 74.6% | 69.3% | 27.6% |

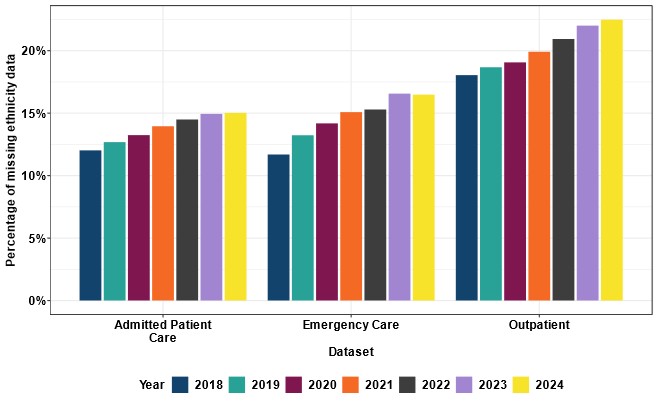

Figure 1: NHS data sets showing declining ethnicity data completeness

The Admitted Patient Care, Emergency Care and Outpatient datasets have seen a steady increase in the proportion of incomplete records over the past 7 years.

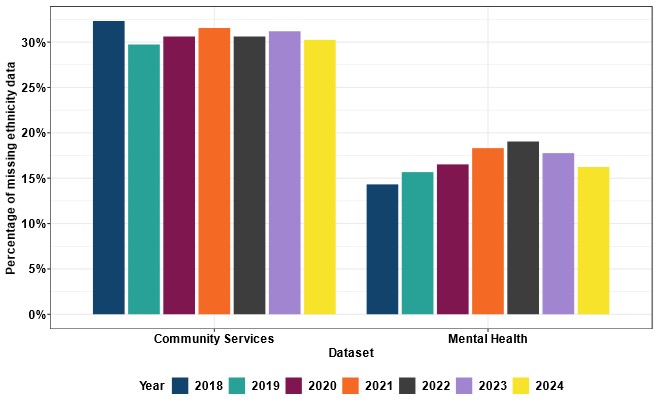

Figure 2: NHS datasets with flat or improving data completeness

The Community Services and Mental Health Services datasets have seen flat or improving ethnicity data completeness in recent years.

Consistency of ethnicity recorded across NHS data sets

We looked at the percentage of individuals appearing in more than one data set in 2023/24 with a valid ethnic code, to show how consistently ethnicity was recorded across those data sets. Where individuals were recorded more than once across datasets, 44% had the same ethnicity recorded each time, 26% had a different ethnicity recorded each time they appeared in datasets, and 31% had some matching records with others showing a different ethnicity.

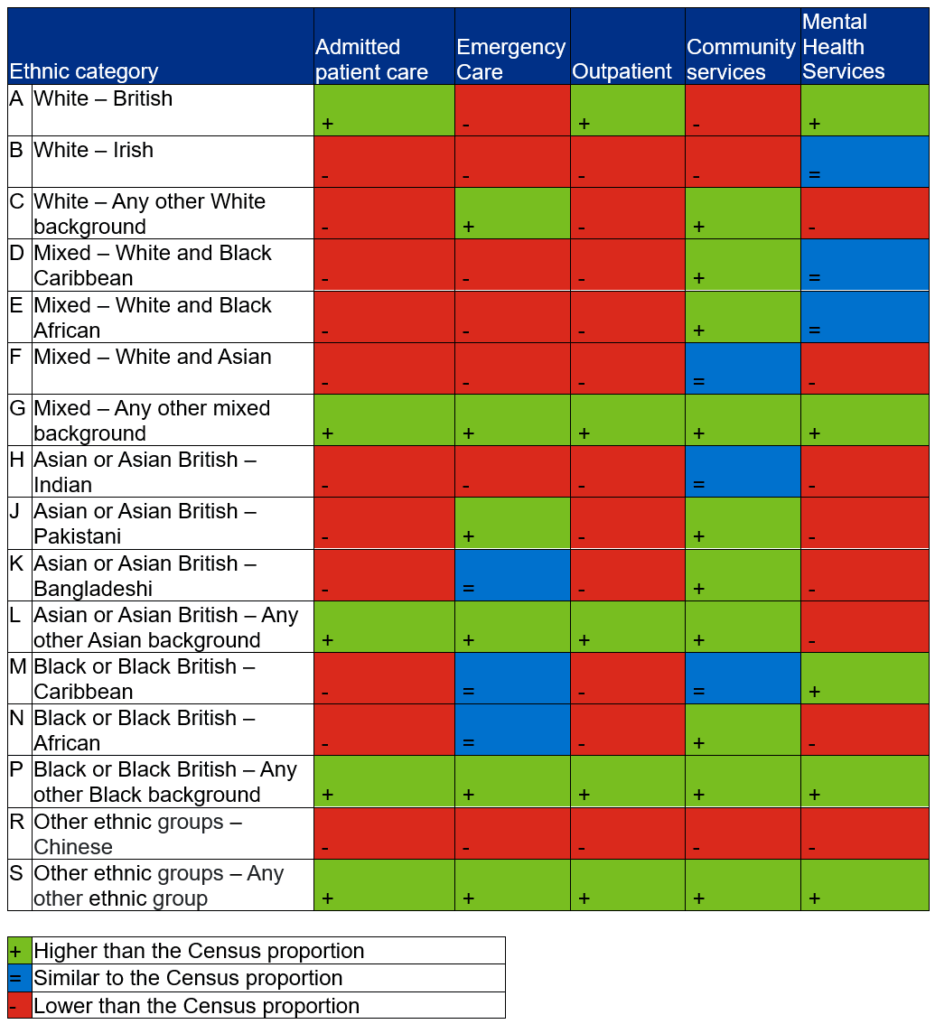

Annex B provides more information on the significant variation in the alignment between different data sets and population-wide Census data.

Domains for improvement

Our research and engagement with stakeholders found challenges across 5 domains for improvement:

- staff lack confidence and skills in requesting ethnicity data from patients, which may lead to gaps (where a person does not have their ethnicity recorded) or increased use of ‘not known’ or ’not stated’ codes

- the public does not understand the purpose of recording ethnicity data and may mistrust requests to provide it, which may result in a higher number of ‘not stated’ codes (where a person declines to share their ethnicity or does not provide the information in a form)

- there are persistent challenges with recording ethnicity data consistently across NHS data sets, which can result in inconsistent codes across records, or ethnicity being recorded in a way that does not reflect a person’s own identity

- issues with data quality and limitations with data sharing can lead to patients being asked to provide their ethnicity multiple times across different services, which frustrates them and increases administrative burden for staff. If the data is poor, it also means it cannot be analysed to understand health inequalities

- perceived challenges with ethnicity data leads to inertia in using data and acting on findings, which can result in a lack of meaningful analysis of healthcare inequalities between ethnic groups and reduce the effectiveness of efforts to improve equity of access, experience and outcomes

A central finding across these domains is that staff training alone will not improve the quality of ethnicity data. Providers must also strengthen the underlying processes and systems that support accurate and consistent ethnicity recording. The following sections set out practical measures to achieve this.

Requesting ethnicity data

Ambition

Staff have increased confidence, knowledge and skills to request ethnicity data from patients, and the tools and resources to do this in a way that reflects a patient’s own identity.

How success can be measured:

- % of records with blank or residual ethnic codes such as ‘not known’ or ‘not stated’ in local and national data sets

- % of patient records with a valid, non-residual ethnicity code (not ‘other’, ‘unknown’, ‘not stated’, or null)

- % of staff who have completed their ethnicity within their staff electronic record

- a reduction in use of residual ethnicity categories (for example, ‘any other background’ or ‘not known’) at provider, ICB and national level

Evidence and engagement with stakeholders suggest there are barriers and enablers for staff when requesting ethnicity data from patients:

- capability: a lack of training and guidance can contribute to staff not having the confidence or skills to ask patients about their ethnicity or explain to them why it is being collected. Upskilling staff to have a culturally competent and direct conversation with patients where they could communicate why ethnicity is recorded is an important enabler

- capacity: in some clinical settings, asking patients to self-report ethnicity may be more challenging. Some stakeholders have suggested that in emergency clinical settings it is not always appropriate or possible to ask for somebody’s ethnicity information. Where there is confusion about who should collect ethnicity data, this can create further barriers. Being able to draw on existing sources of patient information by breaking down siloes between different services and datasets can help overcome these challenges

High impact actions

Integrated care boards

- Share training materials from providers across your system, highlighting approaches where staff demonstrate higher confidence in requesting and recording ethnicity data. Use data completeness or qualitative insights to identify and learn from effective practices.

- Provide tailored support to build staff capability and capacity to request and record ethnicity data, focusing on providers and non-NHS organisations with the lowest ethnicity data completeness.

- Embed clear standards and expectations for ethnicity data collection within service-level agreements and procurement processes for direct care providers – including independent and voluntary sector providers. Monitor data completeness as part of quality and performance reviews, using existing contractual levers where relevant, and embedding data quality requirements in new contracts where possible.

Providers

- Make ethnicity a mandatory field in electronic patient records, with clear prompts and a formal ‘prefer not to say’ option to avoid blank entries. Ensure systems flag missing data and require appropriate action before moving forward.

- Incorporate ethnicity recording metrics (for example, proportion of valid entries, proportion of ‘not stated’ codes) into quality dashboards and governance reports to track progress and identify areas and teams requiring additional support.

- Ensure clinical and administrative staff can easily access guidance and resources to support direct yet culturally sensitive conversations with patients, making sure they understand that assuming a patient’s ethnicity is unacceptable. Co-design scripts with patients from diverse backgrounds to ensure language is culturally appropriate and not intrusive.

- Regularly review teams’ or departments’ ethnicity recording rates and share this data with admin teams to close the feedback loop and support targeted improvement efforts. Timely, local feedback improves data quality, builds ownership and helps staff understand their role in tackling inequalities. Celebrate improvements and offer tailored support where rates remain low.

- Include admin teams in quality improvement efforts and ask for their insights on what feels awkward or difficult about asking these questions and how to make this easier.

- Share examples of how ethnicity data is being used to improve health outcomes locally or to influence national policy development.

- Embed clear standards and expectations for ethnicity data collection within service-level agreements and procurement processes for direct care providers – including those in the independent and voluntary sectors providers. Monitor data completeness as part of quality and performance reviews of services and use contractual levers.

Case study – Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust

Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust provides physical, mental health and learning disability services to children and adults. It operates out of approximately 50 sites, caring for a population of about 1 million.

What needed improving?

The trust used a coaching approach to improve ethnicity recording across the organisation. This was part of wider efforts to provide equity in access to services, reduce poorer health outcomes and improve the experiences of ethnic populations.

How was the improvement designed?

A co-production approach was used. A named coach and colleagues from the trust (including health equity leads) identified the main aspects for improvement as:

- enhancing the capability of staff to request ethnicity information from patients

- improving managers’ understanding of the importance of ethnicity recording within their services

- developing trust leaders’ understanding of how improved ethnicity recording could provide system benefits

What was expected to change?

The trust aimed to:

- help frontline teams to ask for ethnicity data

- improve healthcare decision-making

How was the improvement delivered?

An initial diagnostic phase consisted of interviews with service managers and a staff survey to identify challenges with ethnicity recording. This fed into a trust-wide communication and engagement plan. Coaching was structured around 3 questions:

- why is accurately capturing ethnicity data important?

- based on your experience, what do we need to consider?

- what would an effective approach look, sound and feel like?

The coaches provided an evaluation report with actionable recommendations for improving staff understanding of and confidence in ethnicity recording.

What improved?

- staff understanding of disparities in health outcomes of ethnic minority patients

- staff awareness of the importance of using ethnicity data for commissioning healthcare

- changes in ethnicity recording practice by frontline staff

- access to ethnicity recording resources

Patients providing ethnicity data

Ambition

Patients have increased confidence that the ethnicity data they provide will be treated appropriately and used to improve their care.

How success can be measured:

- % of records with an ethnic category of ‘not stated’ in local and national data sets, reflecting reductions in the number of people preferring not to give their ethnicity

Guidance highlights that self-reporting is the most effective and accurate method for capturing an individual’s ethnic identity. However, patients may not always feel comfortable disclosing their ethnicity. The factors that influence whether patients share their ethnicity data with healthcare staff are:

- communication: the role of ethnicity data in improving services is rarely explained and multiple requests for ethnicity data can confuse patients who expect this information to be held across the NHS. People or communities with poor experiences of and low trust in healthcare (or wider statutory) services can be particularly reluctant to share information because of fears of discrimination. Clear communication is an important part of improving trust and confidence

- identity: the language and categories people use to describe their ethnicity are continually changing, which introduces variation in how individuals identify and respond to ethnicity questions

We can learn from international experience including the European Union’s work on Roma health and New Zealand’s approaches to data governance in partnership with the Maori community.

High impact actions

All stakeholders

- Recognise that an individual’s identification with ethnicity, language and religion, and their willingness to share this information with the NHS, is dependent on previous experiences (including discrimination).

Integrated care boards

- Work across systems and providers to identify local healthcare champions for improving ethnicity recording, ensuring they have credibility with the communities they serve. Build on previous health inequalities champion work (for example, from during the Covid-19 pandemic and the vaccination programme).

- Continue work to coproduce interventions to address ethnic healthcare inequalities, recognising that building trust around ethnicity data involves addressing the root causes of mistrust. Efforts should be made to reach seldom-heard groups.

- Issue guidance to eliminate the practice of determining ethnicity by observation and share guidance on self-identification with all staff.

Providers

- Offer clear, accessible communication to patients at the point of requesting ethnicity information – outlining why it is being collected and how it will be used to improve care. Communication should meet varying literacy levels and language needs, in line with the Improvement framework for community language translation and interpreting services. Translated materials should be available where needed.

- Help staff have open conversations with patients about the benefits and perceived risks of ethnicity data, including providing basic information about how this data is stored, shared and used.

- Use a range of communication approaches and ensure messages are relevant, help build trust and are available in a range of languages.

- Routinely review these communication approaches with input from patients and community groups to ensure information is accessible for target populations, including those with limited digital access.

- Issue guidance to all staff to stop the practice of determining ethnicity by observation and to support them to record using patients’ self-identification and build this into systems used to record ethnicity.

Case study: Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust

Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) is a specialist children’s hospital. Annually, 76,000 children are seen at GOSH from across the UK for care and treatment.

What needed improving?

- Some staff felt worried or ill-equipped to ask patients and parents or carers about their ethnicity.

- Building trust with patients and families by clearly explaining why potentially sensitive information – such as a child’s, parent’s or carer’s ethnicity – is being requested, and how it will be used to improve care.

How was the improvement designed?

The Digital Health Inequalities working group, which reports to GOSH’s Health Inequalities Steering Committee, designed an improvement initiative on how staff ask for ethnicity data.

The areas for improvement identified were:

- equipping staff members with the skills and prompts to ask patients and their parents or carers about their ethnicity

- updating staff guidance on requesting ethnicity data from patients and their parents or carers

- raising staff awareness that patients and families can update their ethnicity data through the MyGOSH patient portal

- providing information for patients and their families on why ethnicity information (and other demographic data) is requested

What was expected to change?

GOSH set out to improve recording by supporting staff to ask for ethnicity information and helping patients and families feel able to give it.

How was the improvement delivered?

Through co-production activities with staff, GOSH:

- ensured the ‘Updating Patient Ethnicity in Epic’ guidance, which specifically looks at patient records with missing ethnicity information and how to address this with the patient or the parent/carer, was updated and disseminated to all admin staff, including through online training. This included a flow chart for ethnicity data completion and all options for data entry, including for patients, parents or carers to complete this themselves through the MyGOSH patient portal

- posted screensaver prompts to remind staff to record ethnicity data and direct them to the updated online training

- provided information on its website for patients, parents and carers on why they might be asked for ethnicity and other demographic information. This information was provided in English and 10 other languages

- displayed posters across the hospital with a QR code linking directly to the webpages

What improved?

A small increase in ethnicity data completion has been noted in the early stages of the project.

Recording ethnicity data

Ambition

Ethnicity data in healthcare data sets is consistently recorded to modernised categories across data sets.

How success can be measured:

- a statistically significant reduction in the recording of multiple ethnicities for one patient across different data sets (for example, across primary, secondary and community care)

- % improvement in ethnicity data completeness among independent sector providers delivering NHS-funded services

- an increase in the level of consistency between individual-level ethnicity recorded in healthcare data sets and Office for National Statistics Census data and analysis

- % of patients accessing and updating their own ethnicity information through digital platforms when available (for example, the NHS App)

Stakeholders have highlighted that the use of 2001 Census ethnicity categories in the NHS – rather than 2021 categories – hampers detailed analysis to tackle healthcare inequalities because it does not reflect the ethnic diversity of England in 2025 and contributes to incomplete ethnicity recording in patient administration systems. It also makes it more difficult to make meaningful comparisons between NHS data and population-level data sets that use different ethnicity classifications. Inequalities within ethnic groups can be missed.

Some NHS organisations have created bespoke codes that reflect their local populations. While these may be relevant locally, they need to be mapped back to the ethnicity categories in national data sets to enable comparisons and data linkage between service providers.

Organisational differences in coding contribute to inconsistencies in the recording of ethnicity between settings, even for the same individual across different data sets. This leads to overuse of broad ‘residual’ categories such as ‘any other background’ or of categories such as ‘not stated’, ‘unknown’ and ‘null’. These categories are not always applied consistently, making it more difficult to interpret and analyse the data reliably.

High impact actions

Integrated care boards

- Monitor ethnicity data completeness across all providers (including non-NHS providers), including adoption of new data dictionary standards, when published. Promote consistency in the ethnicity recording for individuals across NHS data sets and reduce reliance on residual codes (like ‘any other background’) where they are overused.

- Work with providers and primary care to identify and address system-level barriers to accurate and complete ethnicity recording.

Providers

- Promote, monitor and feed back on ethnicity data accuracy and completeness on a regular basis – using any decline in data quality as a trigger for organisational action.

- Review the user interface of data systems to optimise ethnicity recording, including considering making ethnicity data fields mandatory alongside, and providing guidance and training for staff on this.

- Provide guidance on the use of ‘Z’, ‘99’ and ‘Null’ codes. Explain how they differ from ‘other’, and ‘not stated’ should only be used when a patient has explicitly declined to share this information.

- Work with teams to share insights on the quality of ethnicity data, helping to inform and drive targeted quality improvement efforts.

- Develop and implement a local data migration plan when updating ethnicity categories to ensure legacy data is mapped accurately to new standards, minimising disruption to existing data sets and analyses.

- Work with clinical and administrative teams to ensure ethnicity recording options are sufficiently detailed to reflect population diversity and are presented in user-friendly formats across both staff- and patient-facing forms (for example, by including free-text options with guidance on how to map responses to standardised classifications).

Processing ethnicity data

Ambition

Ethnicity data is consistently processed to agreed harmonised categories to preserve detail, support robust analysis and make disparities visible.

How success can be measured:

- % of providers adopting the most up-to-date ethnicity categories in line with any new information standard classification

- qualitative assessments by local and national data analysts of the quality of ethnicity data available for analysis and of the success in reducing barriers to meaningful disaggregation of data (due to gaps and quality issues)

Our research and engagement have highlighted the need for more consistency in the sharing and analysis of patient ethnicity data. This includes reducing the number of collection points and linking demographic information to unique identifiers (such as NHS numbers) so that data can be replicated across data sets. This will improve completeness and accuracy and minimise burden on staff and patients.

Integrated care boards

- Adopt nationally developed data science and statistical methods – tailored for local use – to resolve missing or conflicting ethnicity codes. Work with data specialists in the system who have expertise and interest in improving ethnicity data.

- Encourage participation in training, set up local communities of practice for analysts and provide access to resources focused on data linkage, bias mitigation and interpreting ethnicity data in complex settings.

- Allow for more robust and granular analysis of healthcare data by ethnicity and other intersectional characteristics, which recognises wider social determinants of health. Use this to generate system-wide insight for healthcare leaders.

- Participate in national or local research and evaluation activities which can help reduce healthcare inequalities across ethnic groups.

Providers

- Review and monitor organisational practices for sharing ethnicity data to improve the efficiency of how it is requested, recorded and processed.

- Model expected service demand to inform the targeted provision of services for communities experiencing inequalities in service access.

- Identify and invest in staff responsible for analysing ethnicity data by promoting participation in national and system training and supporting communities of practice for analysts.

- Introduce periodic cross-checks of ethnicity data across internal data sets (for example, comparing hospital, GP and community service records) to validate consistency, highlight discrepancies and strengthen overall data quality, particularly for high-priority patient groups.

Case study – North West Neonatal Operational Delivery Network

This is a large network covering Greater Manchester, Cheshire and Merseyside, and Lancashire and South Cumbria, and incorporating 22 neonatal units with a total of 7,000 admissions every year.

What needed improving?

30% of maternal ethnicity data was incomplete in neonatal units across the North West and this both limited insight into inequalities in neonatal outcomes and posed a significant barrier to developing a robust health equity plan.

How was the improvement designed?

The network developed an improvement programme focused on embedding consistent processes for recording ethnicity data at the point of care. All neonatal units in the network were engaged early and co-designed the intervention. They understood the purpose and value of high-quality ethnicity data and identified local enablers and barriers to consistent recording. The emphasis was on integrating ethnicity data collection into routine workflows, rather than treating it as an additional administrative task.

What was expected to change?

The network aimed to improve data completeness and reliability by embedding better collection processes and establishing a feedback loop to drive continuous improvement.

How was the improvement delivered?

A data dashboard served as a tool for driving progress and features included:

- the percentage of ethnicity data recorded by each neonatal unit, enabling benchmarking and targeted peer support for units with challenges

- data assurance information to ensure improved recording remained a priority

- triangulating outcomes with deprivation index and maternal age data. This is part of an ongoing effort to test the integration of multiple data sources to inform interventions that improve outcomes

What improved?

- The proportion of records with complete ethnicity information rose from 70% to 90%.

- The network is working in partnership with analysts – including academic collaborators – to use the improved data for population health analysis and insight.

Using ethnicity data

Ambition

Analysed ethnicity data is used to describe inequalities in access, experience and outcomes, with findings acted on to target outreach, address barriers to access and improve services.

How success can be measured:

- % reduction in ethnic inequalities in access, experience and outcomes across a range of services and care pathways, as determined by local and national priorities including Core20PLUS5

- number of unique users accessing or interacting with disaggregated ethnicity data in NHS Federated Data Platform dashboards (an indicator of engagement and operational use at national, regional and local levels)

- number of Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership national clinical audits that report findings disaggregated by ethnicity and other protected characteristics, including intersectional analysis

High-quality data, robust and creative analysis, responsive local leadership and clear accountability all contribute to the effective use of ethnicity data.

- Analysis: Data analysis will only produce relevant, actionable insights if we tackle bias and errors in the sources, standardise against population-level sociodemographic data and avoid shortcuts. Grouping all diverse groups together and comparing them to White British people may provide an initial headline comparison but is likely to hide real differences between and within communities. Case studies show that when analysts get support – especially with data quality – they produce sharper, more detailed insights that reflect the nuances of ethnic health inequalities.

- Data visualisation: Embedding functionality to view disaggregated data by ethnicity makes healthcare inequalities visible at service, provider and system level, allowing for both collective and individual action to tackle healthcare inequalities. Data disaggregated by ethnicity should be reviewed alongside analysis by deprivation, and standardising by age will support a more robust analysis. To ensure the data leads to meaningful action, it should be combined with other insight sources to provide context and generate actionable findings.

- Leadership: Disaggregated data must inform evidence-based discussions about service planning, quality improvement and resource allocation – and senior leaders should insist on embedding healthcare inequalities insight in their service intelligence.

High impact actions

Integrated care boards

- Promote and coordinate cross-system action on ethnic health inequalities, in line with ambitions set out in the model ICB blueprint.

- Support system-wide analytical collaboration to generate insights into ethnic health inequalities.

- Facilitate cross-disciplinary collaboration, bringing together those with relevant professional expertise (such as information governance or data analysis).

- Co-produce specific actions on health inequalities with communities (being mindful of the emotional and psychological investment participation requires of co-producers).

Providers

- Champion national and system initiatives to use ethnicity data to support action on healthcare inequalities.

- Embed the routine use of ethnicity data into service planning and delivery by requiring teams to review data trends when designing, delivering or adapting clinical pathways, outreach activities and service models.

- Encourage services to use ethnicity data alongside other patient demographics (for example, age or deprivation) to identify variation in access, experience and outcomes, and adjust service delivery accordingly. This might, for example, involve appointment booking processes, clinic locations, clinic times or community engagement strategies to better meet the needs of underserved ethnic groups.

- Ensure that healthcare inequalities insights drawn from ethnicity data are incorporated into divisional and organisational quality improvement plans, with senior leadership oversight and regular reporting to governance boards.

- Design and implement routine evaluations of service changes or interventions (such as new outreach programmes or access pathways) that are informed by ethnicity data and inform continuous improvement.

- Give senior leaders tailored support to help them provide inclusive leadership, as set out in the NHS People Plan and the NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard. Use Core20PLUS5 to prioritise actions, build safe and supportive working cultures, and make sure leaders are responsible for equitable outcomes in service design and staffing.

- Include the risks of not addressing ethnic health inequalities in service and organisational risk management plans, along with documented mitigations.

Case study – Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust

This trust provides community health services to more than 4 million people across 14 London boroughs and Hertfordshire.

What needed improving?

Missing ethnicity data was affecting the trust’s ability to understand and act on unequal access to services.

How was the improvement designed?

The trust’s health inequalities leads talked to staff about the barriers to ethnicity recording. They identified 3 main issues:

- ambiguity around which staff group (administrative or clinical) should ask for ethnicity data

- a lack of confidence among staff in requesting ethnicity data from patients

- uncertainties and inconsistencies in how to record ethnicity in databases, resulting in incomplete recording

How was the improvement delivered?

A staff engagement and education programme raised awareness of the importance of ethnicity recording and included:

- a script for staff to use when asking for ethnicity information from patients

- trust-wide communications emphasising that recording ethnicity was everyone’s responsibility and not that of a particular staff group

- a video demonstrating how to enter ethnicity data into databases and FAQs to further support ethnicity data entry

The training was followed up with more targeted communications that included:

- sharing lessons from teams who improved ethnicity recording

- using a dashboard on the intranet to share the data on improvements

- offering targeted support to teams struggling to make improvements

What improved?

The proportion of records with complete ethnicity information rose from 78% to 93%.

Annex A: Interim guidance on reference data to identify ethnicity

NHS England currently uses different sets of reference data codes to identify ethnicity across several data products, pipelines, datasets and information standards.

NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care are working on a joint programme on recommendations to improve data around protected characteristics, including the way ethnicity is identified in NHS data. This work is still ongoing and, as it continues, there is a need to align approaches as far as possible on the identification of ethnicity in health and care to avoid further divergence and lack of clarity.

In parallel, the Government Statistical Service (GSS) is currently working on a new iteration of the harmonised ethnic group question design, with a view to establishing a new harmonised ethnicity standard. This will also inform future Census questionnaires. Findings are to be published soon, giving an indicative timeframe for this standard to be published in December 2025.

Accordingly, to address the existing guidance gap NHS England is recommending that, if the design of a new product cannot wait until the joint Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England-led standards are published, it should make use of latest ethnicity standard which is Census 2021 ethnicity codes. This follows the GSS Standardisation recommendation*.

If you are currently using any other ethnicity codes in an existing implementation, we recommend that you do not make any changes for the time being until the GSS guidance is published. However, we do recommend that you familiarise yourself with the ethnicity groupings defined by Census 2011 and 2021, as these will be mappable to any new standards developed by GSS.

This guidance will remain in place until new recommendations are published, and work can be completed to develop information standards that constitute official policy and as such will establish a longer-term solution. Note that this advice is intended as best-practice guidance for anyone in the NHS seeking clarification on which ethnicity codes to use for their data products and does not constitute official policy.

This guidance was published on FutureNHS in April 2025.

* In June 2025, a private members bill, the Public Body Ethnicity Data (Inclusion of Jewish and Sikh Categories bill, is due to receive its 2nd reading. If the Bill receives royal assent, organisations will be required to monitor Jewish and Sikh categories as ethnic identities.

Annex B: Consistency of NHS ethnicity recording with Census data

There are significant variations between the representation of some ethnic groups in NHS data and their representation in population-wide Census data. For example, generic classifications, including “Mixed – Any other mixed background”, “Black or Black British – Any other Black background”, and “Other Ethnic Groups – Any other ethnic group” have greater representation in the data sets than in the Census.

Annex C: A note on language

When referring to ethnicity in this plan, we have adopted the NHS Race and Health Observatory’s principles of:

- being specific – we are as specific as possible about who we are talking about

- using collective terminology only when necessary – this plan refers to ethnicity data as a broad category, and where we refer to specific groups or communities, we use context to guide the most appropriate use of language

- not using acronyms – we do not use acronyms such as ‘BAME’ or ‘BME’ in this plan

- adaptability – we acknowledge that no single term suits everyone. As language evolves, we need to evolve our approach to ethnicity recording

Ethnicity and race are commonly used interchangeably. However, while race is a categorisation based mainly on physical attributes and traits such as skin colour, ethnicity is a broader construct and can reflect wider characteristics such as cultural experiences, traditions, ancestry, language and national identity.

Ethnicity is not synonymous with race in this document. Some ethnic groups are racially minoritised and experience health inequalities linked to racism and structural discrimination. However, health inequalities can affect people across all ethnic groups and often intersect with other factors such as deprivation, poverty, trauma, abuse and neglect. This, in turn, can contribute to homelessness, worklessness, social exclusion, digital exclusion, substance misuse, domestic violence, contact with the criminal justice system and mental ill health.

Health inequalities can also vary within and between people of different ethnic identities and in relation to other protected characteristics such as religion, disability, age and gender. Therefore, these variations must be considered when using ethnicity data to understand disparities in access, experience and outcomes.

Publication reference: PRN01931