Purpose of this guidance

This guidance supports general practitioners (GPs) to fulfil their contractual requirement around the maternal postnatal consultation. Since the GP contract regulations were amended in 2020, there is a contractual requirement to offer women a maternal postnatal consultation by a GP, between 6 and 8 weeks postnatally.

This guidance provides clear national advice to address unwarranted variation for the delivery of safer, more equitable, more personalised care. While this guidance does not override GPs’ clinical discretion in accordance with their professional duties, they should take it into account in delivering and organising the maternal postnatal consultation unless they can articulate a valid reason to do otherwise.

The consultation must be a separate appointment from that for the baby check, though the two may run consecutively. Women should be sent an invitation to the consultation, and an outline of what they can expect from it and what will be discussed. The invitation should be appropriately tailored to women’s circumstances particularly in cases of bereavement or separation from the baby. If the woman has had a prolonged postnatal hospital stay or has a child in neonatal care, offer the postnatal consultation as soon as she feels able to attend, even if beyond six-eight weeks.

We developed this guidance in co-production with services users and professional stakeholders; and would like to thank the Royal College of General Practitioners, GPs Championing Perinatal Care, Royal College of Obstetricians Gynaecologists, Institute of Health Visiting, Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy, London Maternal Clinical Network, North-East London Maternal Medicine Network, Barts Health NHS Trust, Office of Health Improvement and Disparities for their contribution.

Providing high quality postnatal care can impact on both short and long term maternal and infant health. MBRRACE data showed that maternal deaths are much higher postnatally than antenatally. There are an increasing number of women experiencing more complex pregnancies due to multi-morbidities, with women requiring support for a range of physical and mental health issues and complications following birth. This postnatal GP contact is an ideal opportunity to monitor and provide support and interventions for the women that require it.

This document will be updated as necessary. To feed back on its content, please contact the NHS England team via england.maternitytransformation@nhs.net

Consultation principles

- All GPs should be trained to undertake this consultation in GP specialty training and should seek to update their knowledge and skills on a regular basis and commit to quality improvement.

- The consultation is universal: it should be offered to all women, including those whose baby has died or does not reside with them for any reason (e.g. surrogacy, local authority care).

- In delivering the postnatal consultation consider equity in access, experience and outcomes for specific groups.

- Some women have conditions that developed in pregnancy or were affected by pregnancy or breastfeeding and require follow-up in primary or specialist care.

- This consultation should be holistic and balance how physical and mental issues can impact each other.

- Even if a woman’s physical or mental health issues have been reviewed by a specialist, she should still be offered a GP postnatal consultation.

- Birth trauma is common and can be unexpected. It can happen after any birth, even if the birth seems to health professionals to have been uncomplicated. It can affect both parents. Ask directly about the birth experience, even if there are no reasons to suspect birth trauma. It may be appropriate to offer the woman a further appointment if she wants to discuss something about the birth, for example if she needs more time or doesn’t want to discuss it immediately.

Conducting the consultation

In line with NICE guidance, the maternal consultation should be carried out by a GP and focus on:

- Perinatal mental health: a review of the mother’s mental health and general wellbeing, using open questioning.

- Physical health: the return to physical health following childbirth and pregnancy; any conditions that existed before or arose during pregnancy that require ongoing management, e.g. gestational diabetes and high blood pressure.

- Pelvic health: early identification of pelvic health issues.

- Family planning and health promotion: contraception, family planning and long-term health promotion.

The GP should respond to any concerns, which may include further investigation and referral to specialist services provided in secondary care or other community services and by other primary care team members, such as social prescribers and nurse practitioners.

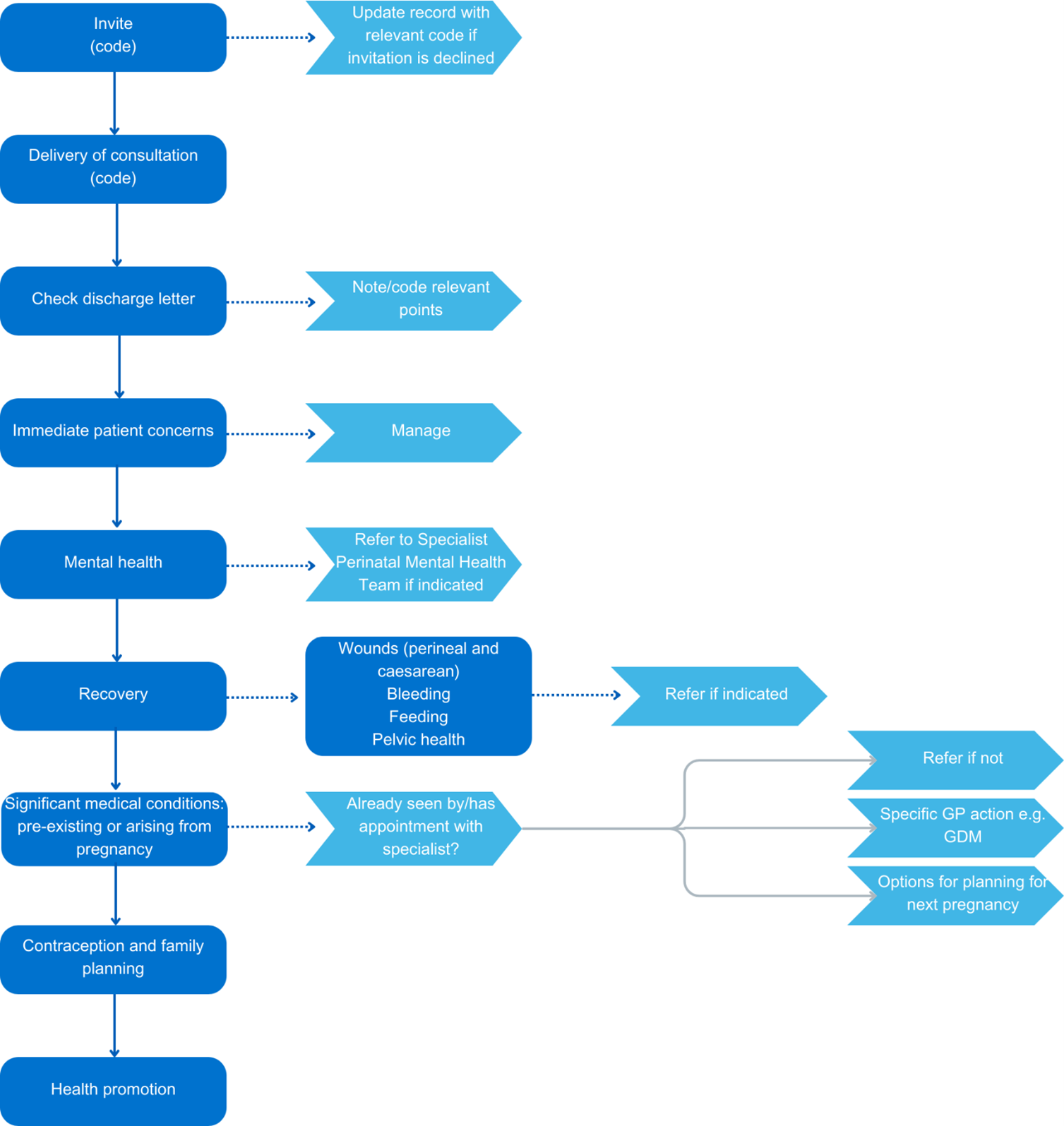

A flow chart summarising the consultation process and the SNOMED coding commonly used for reporting this consultation are provided in further information.

How to conduct the consultation

- Review the maternity discharge letter and note any specific issues that have arisen.

- Note any pre-existing conditions whose management may have been paused or altered by pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- Ask the woman if she has any specific concerns to discuss.

Start the consultation with open questions

The following open questions are a good way to begin the conversation:

- Would you like to talk about your experience of the birth?

- How are you finding being a mum/mother?

- Is being a mum how you imagined it would be?

Adjust the questions as appropriate to the woman’s situation; for example, depending on whether she has had her first child, or her baby has died or does not reside with her.

Ask about mental health problems

Ask every woman, every time about her mental health. Never assume someone else has already asked her. Also, although a woman may have seen several healthcare professionals during her pregnancy and postnatal period, she may not have disclosed any symptoms of mental ill-health.

Identifying and addressing serious mental illness (severe depression, psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and postpartum psychosis) takes priority in the appointment over other areas of the consultation that can be reasonably addressed at a subsequent planned appointment.

Red flag presentations for suicidal risk – referral for urgent psychiatric assessment

Successive confidential enquiries into maternal deaths suggest that women with the following signs/symptoms may be at higher risk of suicide and require urgent referral to a local specialist perinatal mental health (PMH) service. Use your local pathway or emergency crisis perinatal pathway (urgent referrals should be made by phone and triaged by the team within 4 hours):

- recent significant change in mental state or emergence of new symptoms

- new thoughts or acts of violent self-harm

- new and persistent expressions of incompetency as a mother or estrangement from the baby.

To assess complexity/severity ask about or keep in mind:

- intrusive thoughts or images: distressing thoughts/hallucinations/hopelessness

- behaviours/actions: self-harm, sleep, irritability, strict routines

The perinatal mental health section of below provides detailed information about prevalence, risk factors, treatment options and resources.

Ask about breast health/infant feeding

Women choose to feed their baby in different ways; ask in a non-judgemental open way about any difficulties they may be having feeding their baby. “How is feeding going?” is simple but a useful start to the conversation.

Adjust the question to reflect the woman’s situation; for example, their baby may be in neonatal care.

The infant feeding/breastfeeding section provides further information, including on drugs in breastfeeding and vitamin D for breastfeeding mothers.

Ask about physical recovery

Even the most straightforward, uncomplicated births are physically demanding, and for all women the postnatal period is one of physical recovery and healing.

To assess how well a woman is recovering from pregnancy and birth cover the following areas in the consultation:

Wound healing (caesarean and perineal)

Ask the woman if the wound is causing discomfort and whether it appears to be healing. Offer to examine if there are any problems. If the perineal wound is broken down, or there are ongoing healing concerns, refer the woman urgently to specialist maternity services.

Perineal health

Although most mothers experience some perineal pain after giving birth, this will usually have resolved by the time of the postnatal consultation. For those reporting ongoing pain, offer to undertake an examination and consider if referral is required. The perineal health section below provides further information about the management of perineal health.

Pelvic health

Ask about the four areas of pelvic health:

Bladder

- Have you had any problems with leakage of urine/wee, either when you cough/sneeze/laugh or have a strong urgent need to pass urine/wee?

- Any pain when or difficulty emptying your bladder/weeing, including a feeling of incomplete emptying?

Bowel

- Do you struggle to get to the toilet in time when you need to empty your bowels/poo? Is your underwear ever stained/soiled?

- Do you find that you can’t control your wind? Or any problems emptying your bowels/pooing?

- Some women need to use their finger to help empty their bowel/poo; have you felt the need to do that?

Vagina

- Have you had any heavy, dropping, dragging feeling in your vagina?

- Some women describe this sensation as like a tampon having slipped, especially when they have been standing or lifting, or towards the end of the day?

Sexual

- Has sex been a problem for you since giving birth? Do you have any questions about resuming sex?

Referral onward

If a woman has symptoms or she is in an at-risk category for pelvic health problems (see NICE guideline Pelvic floor dysfunction: prevention and non-surgical management), consider referral to a perinatal pelvic health service (PPHS). Each GP practice should be aware of the locally agreed referral pathway into the PPHS or specialist pelvic health physiotherapist, also known as a women’s health physiotherapist.

The pelvic floor health section below provides further information.

Postpartum bleeding

Most women will have stopped bleeding vaginally by the time of their postnatal consultation. If they have not, consider if this is atypical persistent or heavy bleeding suggesting retained products of conception which may require specialist referral via locally agreed routes.

Ask about pre-existing medical problems and ongoing management of significant medical conditions arising from pregnancy

Ensure optimal management of any pre-existing medical problems particularly where this changed due to pregnancy. Women who have had complications through pregnancy may already be aware of the potential longer-term implications for their health, but it is important to understand what they already know about their health conditions.

Check that appropriate follow-up is in place for those with significant medical conditions.

Further information for significant medical conditions (listed alphabetically).

Ask about contraception and family planning

The postnatal consultation provides an important opportunity for contraceptive health needs to be assessed. Women should be asked about contraception and supported to make planned choices about future pregnancies. This will help to prevent unwanted pregnancy and to improve future perinatal outcomes through optimum spacing between children. See section on contraception and family planning in further information.

Provide health promotion advice

The postnatal consultation is an opportunity to sensitively deliver health promotion advice and identify if the woman needs support postnatally to improve health outcomes. Consider the following areas:

- smoking cessation and preventing relapse

- weight

- physical activity

- cervical screening

- vaccination programmes.

Further information about these health promotion topics is provided in further information.

Consultation flowchart and SNOMED coding

You may find this resource helpful as a quick reference for the suggested flow of the consultation.

The SNOMED codes below are those most commonly used nationally to report the GP 6–8-week postnatal maternal consultation. Selecting from these will help standardise coding, for consistency in data collection at a practice and primary care network level.

|

Stage of consultation |

SNOMED code |

Code description |

|

Invitation |

880551000000105 |

Postnatal examination first invitation (procedure) |

|

880461000000109 |

Postnatal examination invitation (procedure) | |

|

880531000000103 |

Postnatal examination second invitation (procedure) | |

|

880481000000100 |

Postnatal examination third invitation (procedure) | |

|

444020006

|

Maternal postnatal examination declined (situation) | |

|

Consultation |

384636006

|

Maternal postnatal 6-week examination (procedure) |

|

384634009

|

Postnatal maternal examination (procedure) | |

|

444136005

|

Maternal postnatal examination done (situation) | |

|

384635005

|

Full postnatal examination (procedure) | |

|

185266004

|

Seen in postnatal clinic (finding) |

Further information

Health inequalities and improving access

For some people in the UK there are inequalities in their health outcomes as well as their access to and experiences of NHS services.

In delivering the postnatal consultation consider equity in access, experience and outcomes for specific groups (1).

There are some practical initiatives that can be implemented to improve access, experience and outcomes for all women. These initiatives include:

- provision of interpreter and translation services

- active follow-up processes when women are not able to attend

- personal appointment invitations and reminder text services

- standardised processes for information management when a baby dies or is removed by social care, ensuring the provision of the consultation is prioritised for these women

- local promotion campaigns for the maternal consultation via the GP practice, other local health providers and family focused services

- timing of appointment linked to but separate from the appointment for newborn and infant physical examination (NIPE)

- flexible appointment times that are tailored to women’s needs

- adequate time for those requiring interpreting or translation services, and those with complex needs

- link with wider community resources/services for additional support when the financial cost of access to transport makes attending an appointment more difficult.

System working across multiple services and professionals will be necessary to improve access and support engagement for women with more complex needs. Different populations have different risk and protective factors. Therefore, different approaches are needed for different populations: one size does not fit all. Working with the wider primary care team, health visiting, maternity, social care, perinatal mental health services and other local support resources will provide a range of additional options and approaches.

Needs of specific groups

It is important to tailor the check to each individual, and GPs will be aware of health inequalities within the population they serve. Below are some highlighted factors for consideration when working with the women most at risk of health inequalities. This information can be used to plan and support improving access, experience, and outcomes. This is not an exhaustive list, and it will be important to consider those from other protected characteristic or inclusion groups for whom local data and/or intelligence indicates significant health inequalities need to be considered.

Young mothers

Pregnancy and parenthood at a young age are associated with poor health and social exclusion, and young mothers (those up to the age of 25) are at particular risk of poor mental health (5). The 2022 MBRRACE data showed a significant increase in teenage (19 and under) maternal suicides. Most teenage mothers will require dedicated support, co-ordinated by a health visitor, family nurse, family support worker or other lead professional with the skills to build a trusting relationship. Linking with the wider multidisciplinary team will therefore support access for this cohort of women.

Black, Asian and mixed ethnicity women

Evidence shows that Black, Asian and women of mixed ethnicity experience inequalities in maternity services and wider healthcare, we know that their perinatal outcomes are worse than for white women (2). Discrimination against women from ethnic minorities is known to negatively impact women’s ability to speak up, be heard and their experiences of care (3).

Black women are at greater risk of suffering physical health complications and are more likely to be readmitted in the postnatal period (4), with consequences for both physical and mental health outcomes.

Refugees and women seeking asylum

Refugees and asylum seekers in the UK face significant perinatal health challenges. Refugees are individuals recognized by the UK government as meeting the Refugee Convention criteria, while asylum seekers are those who have applied for asylum but await a decision. The recent MBRRACE-UK (1) report highlights the critical relevance of these issues, documenting the care of recent migrant women with language barriers who experienced stillbirth or neonatal death. The report underscores the impact of systemic inequalities, language barriers, and inadequate support on perinatal outcomes, emphasising the urgent need for improvements in care delivery. These women face disproportionately higher rates of mental health issues, maternal mortality, preterm birth, congenital anomalies, obstetric complications, sexual assault, infant mortality, and unwanted pregnancies, compounded by poverty, social isolation, racism, and stereotyping within healthcare.

To address these challenges, it is important to be aware that proof of address, immigration status, ID, or an NHS number is not required to register with a GP. Asylum seekers are entitled to free prescriptions, and during the “protected period” (34 weeks of pregnancy to six weeks postpartum), the Home Office advises against relocating pregnant women unless they choose to move. This may result in some woman moving just when her postnatal consultation is due. It is important to offer interpreting and translation services for non-English speakers.

Resources

- NHS Guidance: How to register with a GP surgery

- NHS England 2024: HC2 Application for Asylum Seekers

- 24/7 migrant helpline

- NHS language barrier tools

- Home Office Guidance: Healthcare Needs and Pregnancy Dispersal Policy

Gypsies, Roma and Travellers (GRT)

Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities are some of the most excluded in the UK and experience many barriers to healthcare. Women from these communities regularly experience harassment, direct and indirect discrimination and racism (6). It is important for health services to understand the social and cultural needs of people from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities. For example, women may not be aware of the maternal postnatal consultation and so GPs should promote this review and liaise with midwives and health visitors that may have built up trusted relationships within these communities, to promote the service more widely.

Women living in deprived areas

The healthy life expectancy gap between the most and least deprived parts of the UK is 19 years. The reasons for this are complex, not simply a case of having less money, although one in five people in the UK are living in poverty, without the resources to meet their minimum needs (7, 8). Deprivation also means lack of access to resources such as housing, education and services. Ensure families are linked into the local services that can provide financial advice and offer support as required. The Early Help team may be able to provide family support and can be contacted through the single point of access or multi-agency safeguarding hub in each area. They will also be able to refer people to, or offer a voucher for, local food or baby banks.

Resources

- Citizens Advice

- Family Lives

- Gingerbread

- Family Fund; helping disabled children

Bereaved mothers (includes from a stillbirth, neonatal death)

The death of a baby, whatever the timing, is a devastating, isolating and life-changing experience for parents and families. If mothers are supported by trained and informed professionals following the loss of their baby, they are less likely to have psychological problems (9). The postnatal consultation is an important opportunity to assess emotional wellbeing and offer support as required. Some women who have lost their baby may not be aware or consider that the postnatal consultation is for them, and GPs should take active steps to inform bereaved women about it. They should have systems in place to flag these women and ensure they are followed up when discharge documentation is received. Working with health visitors and midwives, they may be able to make the consultation more sensitive to these women’s circumstances; for example, avoiding inviting them to the surgery when a baby clinic is running or NIPE reviews are being completed. GPs may consider referring the mother to a local maternal mental health service for support. GPs should consider, where appropriate, signposting mothers on for lactation management support following loss.

Resources

- Sands; saving babies’ lives, supporting bereaved families

- Stillbirth – What happens if your unborn baby dies

- The Lullaby Trust; bereavement support after the death of a baby or child

- Tommy’s; baby loss information and support

- National Bereavement Care Pathway – eLearning for healthcare

- Information on managing lactation following the death of a baby

Mothers whose baby is in neonatal care

If a baby is cared for on a neonatal unit the family may be under significant pressure and frequently travelling to and from the hospital, making it difficult for the mother to access the GP service. Alternative arrangements to the standard procedure might need to be offered; for example, offering a telephone contact until such time the woman can attend the surgery.

Trans and non-binary parents

In the CQC Maternity Survey (2022) 0.65% of respondents stated that their gender was not the same as their sex registered at birth (10). Intersex, transgender and non-binary people experiencing pregnancy and birth can experience health inequalities including poorer access and a lack of information and support in relation to their specific clinical and care needs within maternity services. The information in this guidance also applies to these individuals.

Trans and non-binary people’s experiences are particularly under-researched (11). Health inequalities can arise in this group if they do not get the same advice and access to health information (12, 13), particularly when health information is thought to be gender specific, for example advice on contraception and cervical screening.

Ask the person what their chosen pronouns are and use their preferred name (14), using inclusive language that is personal to an individual’s situation is crucial in helping them feel recognised and respected. It might be useful to flag this in the electronic patient record so that all communication reflects the person’s wishes and all other professionals that may be in contact with the family are aware.

Women in mother and baby units (MBU)

Some mothers may be being cared for within a mother and baby unit for ongoing support around their mental health, so that they cannot attend their GP for the consultation. MBU’s will need to liaise with local GPs to provide the consultation for these mothers and their babies.

Babies removed into care of local authority

A mother whose baby has been taken into the care of local authority either permanently or temporarily requires a bespoke response to improve access to the consultation. They will have contact with social workers and health visitors so a joined-up approach to deliver care for these women will need to be considered. Women, following the removal of a baby, may not be aware or consider that the postnatal consultation is relevant for them. Therefore, it is important to have systems in place to note these women and ensure follow up is offered.

Resources

- Family Lives: coping with the aftermath of having your children removed by social services

- Child protection resource: the impact on parents when their children are removed

- Parental rights and responsibilities: What is parental responsibility?

Women in detained settings (prison, immigration removal centres)

Women in detained settings have multiple health and complex social needs and face significant health inequalities. These women need a joined-up approach between social workers, health visitors and other healthcare professionals to deliver appropriate care (15).

Domestic abuse

A woman is at increased risk of domestic abuse while pregnant or shortly after giving birth. There is a strong correlation between postnatal depression and domestic violence and abuse. GPs can offer practical support to protect people who disclose abuse and should be aware of the local support services they can signpost women to.

Resources

- NICE public health guideline [PG50]: Domestic violence and abuse: multi-agency working

- Department of Health and Social Care Guidance for health professionals on domestic abuse

Female genital mutilation

This should have been noted on the discharge letter. The GP can provide support for the long term medical and psychological complications women with female genital mutilation may experience.

Resources

- Department of Health and Social Care Female genital mutilation (FGM): resources for healthcare staff

- Department of Health and Social Care Safeguarding women and girls at risk of FGM

Health visiting

Health visitors are registered nurses and/or midwives who have completed additional public health training to become specialist community public health nurses (SCPHN). Health visitors work with all families from pregnancy until the child starts school and play a vital role in promoting the importance of the GP postnatal 6–8-week check to all families.

To find out more about the health visitor’s role in the community – watch this short film by the Institute of Health Visiting.

Perinatal mental health

Many women find the transition to parenthood difficult and perinatal mental health (PMH) problems are common and can have a profound impact at a critical period in women’s lives, including on their relationships, as well as increasing the risk for long-term social, emotional and cognitive problems in their child.

Maternal suicide is one of the leading causes of death within a year of the end of pregnancy; a mortality rate of 3.84 per 100,000 maternities (2).

Most PMH are managed in primary care. However, more severe or complex cases such as severe depression, complicated PTSD, OCD or pre-existing diagnosis of bipolar disorder, should have been referred in pregnancy (even if they were well at the time) and a plan for their pregnancy and postnatal care should have been made available to the GP. Rarely women may develop postpartum psychosis; a mental health emergency that requires urgent referral (within 4 hours), and sometimes they have had no previous mental illness.

Barriers to disclosure

During pregnancy and the postnatal period, women may be reluctant to tell their GP if they are feeling low, anxious or are having intrusive distressing thoughts. In addition to the usual barriers to disclosing mental health problems, there is the pressure of the expectation that they should be enjoying pregnancy or being a mother.

A fear of having their baby taken away is a common reason why some women do not disclose any difficulties. It is important to reassure women that this is extremely rare and only happens in the most severe safeguarding situations.

Risk factors

All women are at risk of experiencing a PMH problem in the postnatal period. However, some previous diagnoses significantly increase the risk, of a woman experiencing PMH problems. These include:

- bipolar affective disorder

- previous episodes of post-partum psychosis

- moderate to severe postnatal depression or anxiety

- previous or current mental health problems prior to or during pregnancy

- previous birth trauma/PTSD

- strong family history of PMH problems.

Treatment and referral

Some issues to bear in mind when considering treatment or referral:

- Self-care –Reinforce the benefits of taking time for self-care. Breaks are a necessity: fatigue is a major contributing factor to worsening symptoms. Discuss with the woman what support they may need to enable this, which may include seeking support from family or friends. Asking about the home environment and whether this feels like a safe space (especially when the woman has attended the appointment alone) can also be helpful.

- Self-help and peer support – online evidence-based self-help and peer support resources and a guide to getting peer support are available.

- Local support – liaise with the multidisciplinary teams in your area to find out what local support and services are available.

- NHS Talking Therapies for Anxiety and Depression – women in the perinatal period should be assessed for treatment within 2 weeks of referral and provided psychological interventions within 1 month of initial assessment (CG192 NICE guidance).

- Referral to local specialist community PMH team –these services specialise in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of women with moderate to severe or complex perinatal mental difficulties. Each local team will have their own criteria for seeing women, but you should be able to refer all moderate to severe or complex cases and seek advice.

- Referral to local maternal mental health service (MMHS) – these specialist services will be in place across England by 2024 for women experiencing moderate to severe or complex mental health difficulties arising from their maternity/perinatal/neonatal experience. This may include birth trauma, perinatal loss (for any reason, including removal for safeguarding reasons) or tokophobia (severe fear of childbirth). MMHS and community PMH teams work closely together to ensure women are directed to the appropriate service.

- Medication considerations –consider prescribing antidepressant medication early and not delay if it is needed. See Drugs in breastfeeding.

- The mother–infant relationship – recognise that some women may experience difficulties with the mother-infant relationship which could be due to a PMH problem. Discuss any concerns that the woman has about her relationship with her baby and provide information and advice. Where needed, liaise with the family health visitor or specialist community PMH team, or parent-infant mental health team if available.

Resources

- NICE clinical guideline [CG192] Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance

- eLearning for Healthcare – 5 module free learning series on perinatal mental health

- Ten Questions on Perinatal Mental Health. Antenatal and postnatal mental health NICE guideline CG192. Practical implications for GPs

- Intrusive thoughts in perinatal OCD

- Maternal Mental Health Alliance

- Tommy’s – Mental health before, during and after pregnancy

- Action on Postpartum Psychosis

- Royal College of Psychiatrists – What are perinatal mental health services?

- Birth Trauma Association

- The British Medical Journal – Identifying post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth

Infant feeding/breastfeeding

If breastfeeding, the woman can be asked if feeding is comfortable, if she feels the baby is satisfied after a feed. An examination can be offered if indicated, for example if there are any concerns regarding nipple pain, mastitis or milk supply.

If breastfeeding has ceased, the woman can be asked if the breasts now feel comfortable and if formula feeding is going well. The conversation around feeding also has relevance to the baby check and any maternal concerns may also be relevant to the infant’s health.

The GP should be mindful that infant feeding problems can impact maternal mental health as well as maternal and infant physical health.

Treatment and referral

Mastitis and some causes of nipple pain may require treatment by the GP but, like all breastfeeding concerns, should also prompt referral for a breastfeeding assessment. A full feeding assessment cannot be made in the GP consultation time period, and the GP should be familiar with local infant feeding/breastfeed support services to signpost rapidly for assessment.

Resources

- For any breastfeeding concerns or support around infant feeding refer on to the local health visitor and/or breastfeeding support services locally who can provide follow up and ongoing support for the woman and her family. Providing mums with information resources from organisation such as La Leche League or Breastfeeding network can also provide support and strategies to overcome feeding challenges (available in different languages).

- The National Breastfeeding Helpline is open between 09:30 and 21:30 every day of the year and women should be signposted to this service if they need breastfeeding support: helpline number 0300 100 0212. Extension of the opening hours to provide a 24/7 service is planned for late 2023 – once live, women will be able to access support during the night when other services may not be available.

- Better Health Start for Life breastfeeding campaign resource centre. Provides free to print or order resources, such as posters and leaflets, plus a variety of digital and social media assets and content.

- The GP Infant Feeding Network (UK) | A Website to Assist Primary Care Practitioners with Best Practice in Infant Feeding (gpifn.org.uk)

- Baby Friendly Resources – Baby Friendly Initiative (unicef.org.uk)

- NICE professional guidance in management of GOR/GORD and CMPA

Drugs in breastfeeding and vitamin D for breastfeeding mothers

Many medications can be safely taken during lactation and if required, support for prescribing in breastfeeding can be obtained from local and national pharmacy, obstetric, maternal medicine or perinatal mental health teams.

Breastfeeding mothers should be encouraged to take daily vitamin D supplements (containing 10mcg) if they are not already doing so.

Resources

- Breastfeeding Medicines Advice service – SPS – Specialist Pharmacy Service – The first stop for professional medicines advice (registration required)

- Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) – NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

- Breastfeeding vitamins – Start for Life – NHS (www.nhs.uk)

Perineal health

Perineal pain may be caused by trauma, stitches, infection and abnormal wound healing and exacerbated by, constipation, haemorrhoids or an anal fissure. Although perineal pain affects most mothers after a vaginal birth, it usually has resolved by the time of the postnatal consultation. If women report ongoing pain, offer to undertake an examination, and consider if referral is required for ongoing concerns.

By the time of the GP postnatal check a perineal wound should be fully healed. While, during the postpartum period, superficial perineal wound infection can be treated with antimicrobials in primary care, significant infection, systemic symptoms, or significant wound breakdown should prompt referral to emergency maternity services (or relevant service according to local pathways) for same day review. Non-acute ongoing healing concerns at the postnatal check should be referred to gynaecology services or the perinatal pelvic health service (see section on pelvic health) as per local criteria.

Be aware that perineal pain that persists or gets worse within the first few weeks after the birth may be associated with symptoms of depression, long-term perineal pain, problems with daily functioning and psychosexual difficulties.

Resources

- NICE postnatal care

- Webb S, Sherburn M, Ismail KMK (2014) Managing perineal trauma after childbirth, BMJ

Pelvic floor health

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a condition in which the pelvic floor muscles around the bladder, anal canal, and vagina do not work properly (19).

Both pregnancy and childbirth can cause short and long-term pelvic floor problems, often worsening around the menopause. Data shows that 67% of pregnant women experience stress urinary incontinence during pregnancy with over 20% developing anal incontinence in the first 5 years after a vaginal birth (16). Longer term complications are estimated at 33% of women experience urinary incontinence after pregnancy (17), a further 10% women experience anal incontinence and around 8.4% of women report symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (18). Pelvic floor problems are significantly under-reported due to embarrassment, shame, or a belief that these problems are ‘normal’. Healthcare professionals can sometimes ‘normalise’ these problems and this can prevent women seeking help.

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a condition in which the pelvic floor muscles around the bladder, anal canal, and vagina do not work properly. The following symptoms and disorders are associated with pelvic floor dysfunction (19):

- urinary incontinence

- emptying disorders of the bladder

- anal incontinence

- emptying disorders of the bowel

- pelvic organ prolapse

- sexual dysfunction

- chronic pelvic pain.

Although a lot of the pelvic health problems experienced by women are common, treatments are available in most cases. Offer reassurance to women, acknowledging that six-eight weeks is still early in the healing process and current problems may resolve with time.

Highlight the importance of physical exercise, pelvic floor exercises and physiotherapy where indicated. Up to 50% of women, when assessed, are not performing pelvic floor muscle exercises correctly (20) so provide information to support them to improve the technique.

If women are presenting with symptoms referral to a perinatal pelvic health service (PPHS) should be considered. This service will provide interventions for the following conditions:

- emptying disorders of the bladder

- anal incontinence

- emptying disorders of the bowel

- pelvic organ prolapse

- sexual dysfunction

- perineal injuries

- perineal wound infection

- chronic pelvic pain

- pelvic girdle pain

- rectus abdominis diastasis

- dyspareunia.

PPHS are responsible for the prevention, identification and access to NICE-recommended treatment for ‘mild to moderate’ pelvic health problems antenatally and up to at least 1 year postnatally. Each GP practice should be aware of the locally agreed referral pathway into the PPHS or specialist pelvic health physiotherapist, also known as women’s health physiotherapist. Specialist pelvic health physiotherapists have undertaken postgraduate training and have the skills to assess pelvic floor dysfunction and prescribe treatment programmes individualised to the patient. They will undertake an examination that includes complete assessment of the anatomy and function, and review of pelvic floor exercise technique. The patient will receive a NICE recommended programme of advice and exercise for a period of 3-4 months.

Resources

- The British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) provides patient information about and tools for managing prolapse and incontinence.

- International Urogynaecological Association Your Pelvic Floor provides resources for patients.

- The Pelvic Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy website provides a range of resources and information for patients

- MASIC – supporting women with injuries from childbirth provides a range of information and resources

Postpartum bleeding

Most women will have stopped bleeding vaginally by the time of their postnatal consultation. If they have not, consider if this is atypical persistent or heavy bleeding suggesting retained products of conception which may require specialist referral via locally agreed routes. Some women may have recommenced menses by the time of the consultation.

Resources

- NG194 Evidence review I (nice.org.uk)

- Prevention and Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage (Green-top Guideline No. 52) | RCOG

Significant medical conditions

The role of the GP is outlined for each alphabetically listed conditions, including treatment recommendations for future pregnancies and contraception.

Anaemia

Anaemia in the postpartum period is defined as haemoglobin of <100 g/L. The maternity team will often have initiated iron supplementation.

It is recommended that oral elemental iron 40–80 mg (e.g. ferrous sulphate 200 mg tablet daily or on alternate days) must be continued for at least 3 months in total after the birth.

If there are symptoms of persistent anaemia once treatment has ended at 3 months, then look at other cause for anaemia.

Cardiac disease

At the postnatal consultation:

Known disease should be followed up by the relevant cardiology team.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Pre-pregnancy risk assessment and counselling is indicated in all women with known or suspected congenital or acquired cardiovascular and aortic disease.

Access website- bumps (best use of medicines in pregnancy) if necessary.

Contraception

The progesterone only pill is suitable for all woman with cardiac disease who are not taking enzyme-inducing medication. A long-acting reversible contraceptive is more effective than the progesterone-only pill. The implant is safe to insert for all women who are not on therapeutic anticoagulation.

Oestrogen-containing contraceptives should be avoided in women with known or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes.

Resources

- Bumps – best use of medicine in pregnancy (medicinesinpregnancy.org)

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al (2018) 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J 39(34): 3165–3241.

- Jakes AD, Coad F, Nelson-Piercy C (2018) A review of contraceptive methods for women with cardiac disease. Obstet Gynaecol 20(1): 21-29.

Chronic kidney disease

Known disease should be followed up by the renal team according to non-pregnant guidelines. Medication: avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatories.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Pre-pregnancy risk assessment and counselling is indicated in all women with CKD.

To reduce risk of pre-eclampsia toxaemia (PET) advise women on the need for low dose Aspirin from 12 weeks’ gestation, if there are no contra-indications to reduce the risk of developing pre-eclampsia.

Contraception

Not covered by UKMEC, but clinical practice guideline on pregnancy and renal disease recommends progesterone-only pill, progesterone subdermal implant and progesterone intrauterine system as are all safe and effective for women with CKD.

Resources

- Wiles K, Chappell L, Clark K, et al (2019) Clinical practice guideline on pregnancy and renal disease. BMC Nephrol 20: 401.

- NICE guideline [NG133] (2019) Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management

Diabetes pre-existing

Return to usual care and treatment after pregnancy. For women who are breastfeeding:

- Metformin and insulin are safe in breastfeeding. During breastfeeding, insulin doses are likely to be lower than before pregnancy. Women should monitor their blood glucose before breastfeeding and have a snack available, especially at night, in case of hypoglycaemia.

- Women with diabetic nephropathy can be treated with enalapril during breastfeeding.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Follow NICE guidance for preconception care for women with pre-existing diabetes.

- Promote good control of blood sugar/HBA1c at the time of conception to reduce poor perinatal outcomes.

- Reduce risk of having a baby with a neural tube defect by advising women with diabetes who are planning a pregnancy to take folic acid (5 mg/day) until 12 weeks’ gestation.

Reduce risk of pre-eclampsia toxaemia (PET)

- Advise women on the need for low dose Aspirin from 12 weeks’ gestation in future pregnancies, if there are no contra-indications to reduce the risk of developing pre-eclampsia.

Contraception

Oestrogen-containing contraceptives should be avoided in women with known or multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease, including diabetes.

Resources

- NICE guideline [NG3] (2015) Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period

- NICE guideline [NG133] (2019) Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

At the postnatal consultation: to exclude persistent hyperglycaemia, offer:

- fasting plasma glucose test 6-13 weeks after the birth, or

- after 13 weeks, if not tested earlier offer fasting plasma glucose test or HbA1c

- do not routinely offer 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test.

Based on the results of the fasting blood glucose test or HbA1c:

- offer a referral into NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme if eligible

- offer an annual HbA1c to those who have a negative postnatal test for diabetes.

Code for gestational diabetes and ensure annual screening is offered. Women diagnosed with gestational diabetes who have negative postnatal testing for diabetes should be offered annual HbA1c testing.

Offer lifestyle advice and support (including weight control, diet and exercise).

Offer referral into the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme if eligible.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Explain the risk of recurrence of GDM in future pregnancies and offer early self-monitoring of blood glucose or an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) as soon as possible after booking in future pregnancies.

Resources

- NICE guideline [NG3] Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period

- NICE quality standard [QS109] (2023) Quality statement 4: postnatal testing and referral

- NICE quality standard [QS109] (2023) Quality statement 5: Annual HbA1c tests

Epilepsy

The postnatal consultation is an opportunity to discuss the following:

- risk reduction, including SUDEP

- safe care of a baby when mother has epilepsy.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

- Medication and its risk for the baby, It is beyond the scope of the GP to amend medication; this requires specialist advice and therefore ensure the women has a follow up appointment with the specialist for any medication changes.

Contraception

Some epilepsy drugs interact with some hormonal contraception. The levonorgestrel-releasing IUS or copper IUD are preferred.

Resources

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health UKMEC April 2016 Summary Sheet (amended September 2019)

- SUDEP Action Epilepsy related deaths

- Epilepsy Action Looking after a baby or young child

- bumps – best use of medicine in pregnancy

Hypertension in pregnancy

Definitions:

- Gestational hypertension: New hypertension presenting after 20 weeks’ gestation without significant proteinuria.

- Chronic hypertension: Hypertension that is present at or prior to the booking visit, or before 20 weeks’ gestation.

- Pre-eclampsia: New onset hypertension (>140 mmHg systolic or >90 mmHg diastolic) presenting after 20 weeks’ gestation and the co-existence of one or more of the following new onset conditions: proteinuria; other maternal organ dysfunction; uteroplacental dysfunction.

At the postnatal consultation

For gestational and chronic hypertension: Check BP

For pre-eclampsia also:

- Check for proteinuria

- If proteinuria (1+ or more) present on dipstick, quantify with urine ACR and arrange a further review 3 months after the birth to assess kidney function (blood creatinine, eGFR and urine ACR)

- If after birth the biochemical and haematological indices were outside the reference range, repeat platelet count, transaminases and serum creatinine as clinically indicated until results return to normal.

If kidney function assessment is abnormal at 3 months, consider referral to specialist renal physicians for assessment in line with the NICE guideline on CKD.

Management

- Offer lifestyle advice (see above).

- Medication: enalapril, amlodipine or nifedipine, and beta-blockers can be used in breastfeeding. Return to usual care and treatment after pregnancy and lactation.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Offer women with chronic hypertension a referral to a specialist in hypertensive disorders of pregnancy to discuss the risk and benefits of treatment.

Advise women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy that the overall risk of recurrence in future pregnancies is approximately 1 in 5 (NICE HiP) and how they can reduce this risk.

Advise women on need to take low dose Aspirin from 12 weeks’ gestation if there are no contraindications to reduce the risk of developing pre-eclampsia.

Refer to NICE guidance on recommended antihypertensives.

Contraception

Progesterone methods are safe and effective.

Long-term health

Advise women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy that this is associated with an increased risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease and kidney disease in later life.

- Offer annual BP check, urine dip for protein and lifestyle advice.

Resources

- NICE Quality standard [QS35] (2019) Quality statement 2: Antenatal assessment of pre-eclampsia risk

- NICE (2022) Hypertension in pregnancy: Long-term health implications

- NICE guideline [NG133] (2019) Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management

- NICE 92023) Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management: Visual summary on antihypertensive treatment during the postnatal period

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP)

At the postnatal consultation

Ask the woman if she still has symptoms (itch).

Check liver enzymes and bile acids. If symptoms or liver function tests are still abnormal at 12 weeks post-partum (total bile acid concentration >19 micromol/) consider other diagnoses, seek advice and referral to hepatologist (21).

Recommendation for future pregnancy

There is an increased risk of ICP occurring in future pregnancies.

Contraception

Follow RCOG and UKMEC2.

Resources

- RCOG (2022) Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Green-top Guideline No. 43)

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (2016) UKMEC2 for CHC

Obesity

Women with class I obesity or greater at booking (BMI >30) should continue to be offered nutritional advice following childbirth from an appropriately trained professional. Explain the increased risk to them from obesity as well as to their unborn child should they become pregnant again.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

To reduce the risk of having a baby with a neural tube defect advise women with BMI >30 who are planning a pregnancy to take folic acid (5 mg/day) until 12 weeks of gestation.

Contraception

Women who have obesity, compared to those with a normal BMI, are at increased risk for other diseases and health conditions, and these comorbidities also need be considered when providing contraception.

Resources

- NICE clinical guideline [CG189] (2023) Obesity: identification, assessment and management

- RCOG (2018) Care of women with obesity in pregnancy (Green-top Guideline No. 72)

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (2019) Clinical guideline: overweight, obesity and contraception

Thyroid problems

At the postnatal consultation

- For pre-existing hypothyroidism: arrange to check thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)

- For postnatal thyroiditis: follow specialist recommendations.

Women may have been treated for subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy, particularly if they had had a fertility assessment. Treatment can often be discontinued postpartum, with repeat thyroid function testing approximately 6 weeks after discontinuing thyroxine replacement.

Recommendation for future pregnancy

Recommend pre-pregnancy TSH assessment.

Contraception

Choice is unaffected by thyroid disease.

Resources

- NICE (2011) Hypothyroidism: Scenario: Postpartum

Contraception and family planning

Fertility can return quickly, particularly if not breastfeeding and ideally an effective contraceptive method should be in place by day 21 post birth (22). The postnatal consultation provides an opportunity for contraceptive health needs to be assessed and to provide advice on the full range of contraceptive methods.

Women should be informed and supported to facilitate planned choices about future pregnancies and improve maternal and child outcomes through optimum spacing between children (22). A UK study reported that almost 1 in 13 women presenting for an abortion or birth had conceived within a year of a previous birth (23). A short interval between pregnancies (<12 months) increases the risk of complications including preterm birth, low birthweight, stillbirth and neonatal death (24).

Not all GP practices may be able to provide the full range of contraceptive options and local care pathways should be in place to ensure access at another GP surgery or sexual health service when needed.

How to approach the conversation

Women should be provided with information about the full range of contraception options and then the method of contraception that is most acceptable to them, if not contraindicated. Counselling about contraception should be sensitive to cultural differences and religious beliefs.

Assessment

- The assessment should cover personal characteristics and existing medical conditions, including those that have developed during pregnancy, which may affect medical eligibility for contraceptive use.

- Check that there has not already been a new pregnancy risk prior to the postnatal maternal consultation. If a pregnancy cannot be excluded at the time, this should not delay starting a method of contraception that does not pose a risk to a future pregnancy. Arrangements should be made for a pregnancy test 3 weeks after unprotected sex.

Choice of method

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare provide guidance on postnatal contraception which covers method-specific considerations.

Contraception started while still under maternity care

- Some women may have already been provided with contraception before discharge from maternity care; check the woman’s understanding of the method if this is the case and provide ongoing supply if relevant.

- If an IUD, IUS or implant has been placed, this should have been communicated by maternity services so that it can be coded with type, date of fitting and date for change.

Quick-starting contraception

- The GP can quick-start any method of contraception at any time in a woman’s menstrual cycle if they are reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant or at risk of pregnancy from recent unprotected sexual intercourse.

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC)

- If a woman wishes to start using a LARC method and this is not available at the time of the consultation or is not appropriate, she should be offered a bridging method of contraception that can be quick-started with clear guidance on where and when to access her method of choice.

Lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM)

- LAM can be up to 98% effective in preventing pregnancy if all the following apply:

- regular exclusive breastfeeding

- the woman is <6 months postpartum

- menstruation has not yet recommenced.

- When using LAM the risk of pregnancy will increase if:

- breastfeeding frequency is reduced or spaced significantly (gaps between feeds of longer than 4 hours during the day or longer than 6 hours at night)

- supplemental feeds or solid food is given

- dummies or pacifiers are used.

Fertility awareness methods (FAM)

- FAM may be difficult to use in the postnatal period due to effects on the signs and symptoms of fertility and ovulation.

Bridging contraception

- Bridging contraception is a short-term supply of the contraceptive pill. It bridges the gap between emergency contraception and longer-term contraception, or postnatally when there is a delay in access to LARCs. This lowers the risk of unplanned pregnancy.

Choice not to use contraception

- If a woman chooses not to use contraception a balanced discussion should be had about her own priorities for fertility, the risks of a rapid repeat pregnancy and advice on pregnancy spacing. She should also be given advice on emergency contraception, when to consider this and local access points.

Sexual health

- Consideration should always be given to women’s risk of acquiring or transmitting sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Condoms may be needed to reduce the risk of STI acquisition or transmission as well as preventing pregnancy, either alone or as back-up to another contraceptive method (22). Be aware of local arrangements for accessing free condoms.

Resources

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare FSRH Guidelines & Statements

- The Family Planning Association (FPA) provides information and decision aids on contraceptive choices, including a Contraception at a Glance tool

Health promotion

Smoking cessation and preventing relapse

Offer women who smoke, or need continued support to prevent relapse, a referral to local stop smoking services. Partners and other household members should also be referred where possible. Advise about maintaining a smoke-free home and ask about:

- Smoking status and that of others living in the family home.

- Inform of the risks of second-hand smoke including higher risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Over a third of SIDS deaths could be avoided if no women smoked during pregnancy and smoking could be linked to 60% of sudden infant deaths (25).

Resources

- Start for Life provides local information about services for women seeking smoking cessation advice.

- NICE (2023) Smoking cessation. Scenario: Pregnant or breastfeeding

Weight

Discuss the benefits of a healthy diet and regular physical activity, taking into account the demands of a new baby. Women who are overweight and want support to lose weight should be given details of appropriate community-based services.

See also Obesity section (under Significant medical conditions).

Resources

- NICE (2010) Public health guideline [PH27] Weight management before, during and after pregnancy

- RCOG (2022) Being overweight in pregnancy and after birth patient information leaflet

Returning to physical activity

Many women wish to return to physical activity following the birth, they should be encouraged to do so, emphasising the importance of pelvic floor muscle exercises.

Resources

Active Pregnancy Project This Mum Moves developed a free e-learning module as part of the Physical Activity and Health programme.

Cervical screening

Check if the woman is up to date with cervical screening. If not advise her to arrange this from 12 weeks postnatal.

Resources

- NICE (2022) Cervical screening

Vaccination programmes

It would also be helpful to review the woman’s vaccination status and arrange for any outstanding vaccines to be administered.

References

- Webster K, NMPA Project Team (2021) Ethnic and socio-economic inequalities in NHS maternity and perinatal care for women and their babies: Assessing care using data from births between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2018 across England, Scotland and Wales. London: RCOG.

- MBRRACE-UK (2023) Saving Lives Improving Mothers’ Care – Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2019-21

- MacLellan J, Collins S, Myatt M, Pope C, Knighton W, Rai T (2022) Black, Asian and minority ethnic women’s experiences of maternity services in the UK: A qualitative evidence synthesis. J Adv Nurs 78(7): 2175-2190.

- Care Quality Commission (2022) Safety, equity and engagement in maternity services.

- Public Health England. A framework for supporting young mothers and teenage fathers. 2016 [cited May 2023]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teenage-mothers-and-young-fathers-support-framework

- Equality and Human Rights Commission (2016). England’s most disadvantaged groups: Gypsies, Travellers and Roma. An Is England fairer? review spotlight report (1 of 4).

- The Health Foundation (2018) Poverty and health.

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2015) Psychological perspectives on poverty. 2015 [cited May 2023]. Available from: https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/psychological-perspectives-poverty

- Ellis A, Chebsey C, Storey C, Bradley S, Jackson S, Flenady V, Heazell A, Siassakos D (2016). Systematic review to understand and improve care after stillbirth: a review of parents’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16(16).

- Care Quality Commission (2023). Maternity survey 2022.

- Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, Hollane CE, Max R, Baral S (2016) Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Transgender Health 2016; 388(10042): 412-436.

- Health4LGBTI. State-of-the-art study focusing on the health inequalities faced by LGBTI people. European Commission; 2017 [cited June 2023]. Available from: stateofart_report_en_0.pdf (europa.eu)

- Williams A (2021) Health inequalities among LGBTQ+ communities. The British Student Doctor Journal 5(2): 88-94. 10.18573/bsdj.267

- British Medical Association, 2022 Inclusive care of trans and non-binary patients. – London: Inclusive care of trans and non-binary patients (bma.org.uk)

- NHS England (2022) Care of women who are pregnant and post-natal in detained settings service specification.

- Gray TG, Vickers H, Jha S, Jones GL, Brown SR, Radley SC (2018) A systematic review of non-invasive modalities used to identify women with anal incontinence symptoms after childbirth. Int Urogynecol J 30(6): 869-879.

- Thom DH, Rortveit G (2010) Prevalence of postpartum urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 89(12): 1511-22.

- Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Clark A, Lapitan MC, Nelson R, Sillén U, Thom D. Epidemiology of urinary (UI) and faecal (FI) incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). 2005 [cited May 2023]. Available from: https://www.ics.org/publications/ici_3/v1.pdf/chap5.pdf

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) NG210: Pelvic floor dysfunction: prevention and non-surgical management.

- Bump RC, Hurt WG, Fantl JA, Wyman JF (1991) Assessment of Kegel pelvic muscle exercise performance after brief verbal instruction.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2022) Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (Green-top guideline No 43).

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Health (2020) FSRH clinical guideline: Contraception after pregnancy.

- Thwaites A, Logan L, Nardone A, Mann S (2019) Immediate postnatal contraception: what women know and think. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 45: 111-117.

- Schummers L, Hutcheon JA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Williams PL, Hacker MR, VanderWeele TJ, Norman WV (2018) Association of short interpregnancy interval with pregnancy outcomes according to maternal age. JAMA Intern Med 178(12): 1661-1670.

- Lullaby Trust (2019) Evidence Base. Available from: https://www.lullabytrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Evidence-base-2019.pdf

Publication reference: PRN00709