A guide for estates leads on building net zero and sustainability into business cases

Overview

This guidance sets out how estates and facilities staff can support the business case for investing in carbon reduction measures, and why this is critical for all NHS organisations.

Key benefits

Reading this guidance will help you to:

- Make the case for green investment, including how it can secure rapid paybacks and cost saving in many cases.

- Be strategic about your green investment – and to demonstrate this clearly in the business cases you develop.

- Prioritise and secure investment that boosts your estate’s energy and climate resilience.

- Identify, capture and argue for synergistic investment across priorities, for example adopting approaches which both tackle backlog and reduce carbon emissions.

- Show that your capital investment is aligned with government and NHS net zero priorities.

- Understand and apply key Green Book requirements.

- Ultimately, improve health outcomes for your patients (and staff).

Key takeaways

Wherever appropriate you should:

- Use valuation of quality-adjusted life years (QALY) gains and avoided greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to create a more holistic overview of the benefits of an action. Factoring these wider impacts into your business case will enable your organisation’s progress against these measures to be tracked.

- Prioritise energy efficiency measures to avoid increasing costs unnecessarily and consider the interventions which address the NHS’ net zero targets. This is in line with the four-step decarbonisation programme set out in the Estates net zero carbon delivery plan (requires FutureNHS log in).

- Consider local health demographics and the natural environment to understand how actions to reduce carbon emissions can have a positive impact on local communities and environments, and work within the integrated care system (ICS) to understand how local populations will be affected by the negative health impacts of climate change and air pollution.

- Look to incorporate net zero and carbon emissions into your organisation’s risk assessment matrix to increase prioritisation of capital investment in these areas.

Introduction

All NHS organisations must take urgent action to address climate change. The UK government has a legal duty to achieve net zero emissions by net zero emissions by 2050.

NHS England, integrated care boards, NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts have a statutory duty to have regard to the need to contribute towards this objective, as set out in the National Health Service Act 2006.

In addition to this, NHS England has, in the report Delivering a ‘Net Zero’ National Health Service, committed the NHS to achieving net zero for its core carbon footprint by 2040 and its wider ‘carbon footprint plus’ by 2045. NHS England, integrated care boards, NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts all have a statutory duty to have regard to this objective.

Beyond the legal case for cutting emissions is the undeniably strong human case: the climate crisis is without question a health crisis, and the impacts of climate-driven health inequalities will fall on the NHS.

More intense storms and floods, more frequent heatwaves and the spread of infectious disease from climate change threaten to undermine years of health gains. Action on climate change will affect this, and it will also bring direct improvements for public health and health equity. Reaching our country’s ambitions under the Paris climate change agreement could see over 5,700 lives saved every year from improved air quality, 38,000 lives saved every year from a more physically active population and over 100,000 lives saved every year from healthier diets.

In 2006, the Stern review made it clear that the costs of climate change inaction far outweighed the costs of action. It estimated that 1% of UK GDP would be needed annually to avoid the impacts of climate change, in contrast to the 5-20% it would take to repair climate damage. Since then, rapid technological advances have lowered the cost of solutions to reducing fossil fuel dependency, and there has been a shift from viewing climate action as a one-time cost or trade-off to a long-term investment and key step to building economic and social resilience.

Given the potential impact of climate change on public health, NHS organisations must lead the way in the UK’s response to climate change, by making environmental considerations central to their decision-making processes, considering the non-market and unmonetizable value of the natural environment, and reviewing the risk of contributing to irreparable climate damage. Beyond efforts to mitigate carbon emissions and protect the environment, organisations must also focus on how resources are used and obtained. Climate change poses a growing threat to ethical procurement and the NHS needs to closely monitor its supply chains to identify potential areas of risk.

Climate action will bring many benefits to the NHS, namely improved health outcomes, employment opportunities, and reduced social and health inequalities. NHS estates and facilities directly control a significant proportion of the emissions that the NHS is responsible for and, as such, must take early and ambitious action.

The strategic case for green investment

This section introduces some of the key strategic benefits from investment in low and zero carbon technologies to the NHS and the wider community.

1. Save money through reduced energy costs

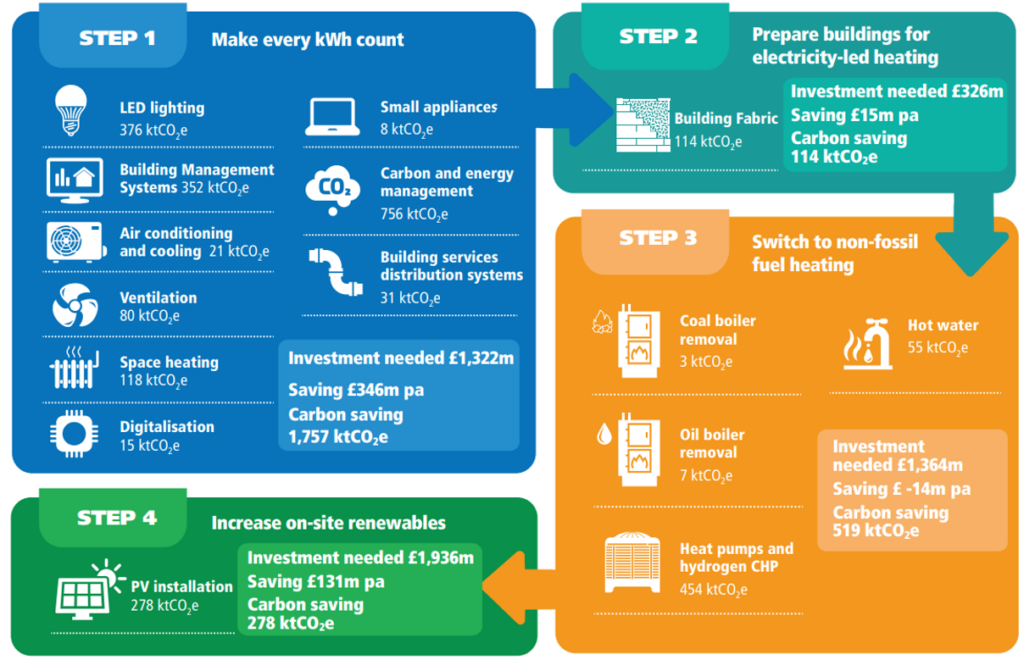

All energy costs increased significantly throughout 2021 and 2022. Many carbon reduction measures have short-term paybacks. For example, the NHS Energy Efficiency Fund launched in 2018 found that on average, the installation of LED fittings across the NHS estate had a payback time of 4.2 years. Step 1 in Figure 1 (below) shows the types of measures that should be considered at the early stage of an organisation’s decarbonisation programme. It is important to first implement measures for increasing building energy efficiency and upgrading building fabric to reduce overall energy demand. This consequently allows for a smaller heating plant to be installed, thus reducing costs further.

Although electricity is currently more expensive than gas, heat pumps are more efficient when used in a properly insulated building. The ‘Estates net zero carbon delivery plan sets out the four steps required to decarbonise the NHS estate (Figure 1).

Figure 1- 4 step approach

Figure 1: Estates net zero carbon delivery plan four step approach to decarbonise the NHS estate by 2040. Figure 1 includes indicative numbers to illustrate the scale of the challenge to decarbonise the NHS estate by 2040. These are not actuals.

The uptake of low-carbon energy and heating also presents an opportunity for significant economic benefit to the NHS through reduced energy demand. The high capital cost of replacing existing heating systems is being supported by government investment in low carbon energy through the public sector decarbonisation scheme.

Case study: Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust energy efficiency

Mid and South Essex NHS Foundation Trust installed an air source electric heat pump at its Broomfield Hospital site as part of the trust’s green plan to decarbonise the estate. The heat pump reduced the trust’s energy consumption by 225,000kWh annually, saving £9,000 and avoiding 49tCO2 emissions per year. Due to the success of the installation at this site, the trust plans to install a solarised heat pump project to its Southend site alongside LED lighting, energy efficient pumps and controls and the use of digital twin software (to create a virtual hot water distribution model of design intent vs real life operation). The project has the potential to save the trust over £50,000 and 146tCO2 a year with a 16-year payback period.

2. Investment can be an opportunity to reduce backlog maintenance

Carbon reduction projects that also reduce backlog maintenance enable estates staff to improve patient and staff experience and enhance the ability of staff to deliver high quality care. Furthermore, any long-term financial gain generated from energy cost reductions can be put towards other elements of service delivery, such as high-risk maintenance issues, new equipment, or additional staff. Adding carbon reduction projects to backlog maintenance business cases and other estates refurbishment works is often more cost effective and less disruptive than installing them separately later.

Research is being undertaken by NHS England to understand the links between investment in backlog maintenance across the NHS estate and achieving net zero carbon. For example, necessary ventilation, roof, or boiler upgrades and replacements also improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions. Highlighting opportunities to tackle the two problems collectively strengthens the economic case for investment in net zero measures.

3. Reduce patient disruption and improve patient outcomes

Behavioural changes in NHS trusts to promote energy efficiency have been shown to improve patient outcomes, as exhibited by Operation TLC developed by Barts Health NHS Trust. Focusing on three key actions of ‘turning off equipment’, ‘lights out’ and ‘close doors’, the scheme saved in energy costs, carbon emissions, and resulted in fewer sleep disruptions for patients. Furthermore, carefully designed changes to lighting and ventilation can reduce discomfort and patient disruption, thus assisting patient recovery. Some interventions, such as LED light installations, lead to reduced maintenance schedules and therefore less disruption in patient areas. Similarly, projects that deliver carbon savings whilst simultaneously reducing backlog maintenance mean that ward or department activities will be interrupted only once when making these essential interventions.

4. Increase energy resilience and reduce future risk of weather impacts

The electrification of heat is likely to increase building electricity use. On-site power generation offers a way for organisations to increase the resilience of their energy supply and to create a buffer against changes to the UK’s energy security and rising energy prices by reducing reliance on the national grid.

Implementing carbon reduction programmes can also provide NHS trusts and providers with an opportunity to introduce adaptation measures. These are measures to protect against or minimise the potential impacts of climate change such as flooding, overheating, water shortages and wind damage. This could include solar shading, sustainable drainage systems and green infrastructure. If not addressed in advance, such impacts are likely to result in future damage costs and possible disruptions to the delivery of care. The National Audit Office has reported that recent investment in flood defences is expected to achieve an estimated benefit-cost ratio of 8:1. There is, therefore, an economic incentive to incorporate adaptation measures and to build resilience in the NHS estate.

Case study: Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust solar farm project

The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust in partnership with Wolverhampton City Council is building a solar photovoltaic farm in a former landfill site the size of 22 football pitches. The farm is designed to generate 6.9MWp at peak times which will help power New Cross Hospital for three quarters of the year – around 288 days of self-generated renewable energy.

The new solar farm will save the trust around £15-20 million over the next 20 years – around £1 million a year – money which will be put back into frontline healthcare. It will generate an estimated carbon saving of 1,583 tons of CO2e per annum.

Carbon savings:

- Conversion factor of grid electricity – 0.25319

- kWh solar farm generation pa – 6,251,810

- Tonnes of CO2e saved – 1,583

Existing green energy sources are already in use at the hospital, including harnessing heat from a waste incinerator, and a combined heat and power system, with most imported electricity coming from the solar farm.

The project, combined with existing green technologies, allows the trust to move away from reliance on the grid and to reduce its exposure to rising electricity costs in the next 20 years. It supports the trust’s goal of reducing its carbon emissions by 25% by 2025, and of reaching ‘net zero’ carbon emissions by 2040.

5. The NHS’s wider influence as an anchor institution

As part of its role an anchor institution, the NHS has significant regional economic influence, in some areas employing up to 7% of the population and having significant spending power. Through collaborating with other anchor institutions, such as local authorities and higher education institutions, NHS organisations can work to address the social determinants of health and health inequalities that will be exacerbated by the effects of climate change and pollution. It is important for organisations to consider their local health demographics, vulnerabilities, and risks to health from climate change, and where their actions can have the greatest impact. For example, by supporting local heat decarbonisation through heat networks, the NHS could indirectly improve local air quality by reducing NOx emissions associated with domestic gas boiler combustion.

Furthermore, the NHS employs 1.3m people, all of whom can be inspired by witnessing positive and proactive responses to climate change taking place within their organisations.

6. Investment can create jobs in the low carbon economy

Energy efficiency and renewable energy projects represent opportunities for the NHS to create jobs and support the growth of the low carbon economy. The government stated that the ‘public sector decarbonisation scheme’ aimed to created up to 30,000 skilled green jobs through phase 1 alone.

Investing in the low carbon economy can also support the development of skills and jobs within the NHS. Procuring and maintaining new low carbon technologies requires the training of current staff. In 2022, NHS England worked with the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Northampton General Hospital NHS Trust to recruit Net Zero Energy Officers, who will complete the two-year junior energy manager apprenticeship. This follows a similar scheme at Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, and paved the way for further planned recruitment at other trusts including the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust.

7. Reducing health inequalities and narrowing the life expectancy inequality gap

There is a social gradient in health: with decreased socioeconomic status comes increased likelihood of poor health. Life expectancy continues to improve for the most affluent 10% of our population but has either stalled or fallen for the most deprived 10%. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the serious extent of health inequalities in England, exacerbating the significant discrepancy in healthy life expectancy between the most and least deprived areas in England. The NHS needs to act in response to all known social determinants of health, including environmental factors. The UK Climate Change Committee Sustainable Health Equity report showed that both the direct and indirect impacts of climate change will widen existing health inequalities in the UK, cautioning that those to feel the worst impacts of climate change will be the most vulnerable populations.

Increasing local investment in climate change solutions is one of the ways in which the NHS can help to target the health inequalities gap through growing and diversifying local employment opportunities. This can lead to long-term positive effects on health outcomes in areas with high rates of unemployment. For example, when several anchor institutions in Preston worked together to redirect more of their spending into the local economy, local total spend with Lancashire-based organisations rose from 39% in 2012 to 79% in 2017, seeing a significant positive impact on local jobs, wellbeing, health, and economic growth.

8. Support the expansion of low carbon energy in local areas

Large hospitals can act as ‘anchor loads’ in heat networks for industrial waste heat and other low-carbon heat sources that are only available at scale. Heat networks supply heat from a central source to a number of organisations or sites. Without anchor loads (generally defined as sites with a large continuous energy demand) these networks would not be economically viable. NHS trusts can therefore support the expansion of district heating, providing affordable low carbon heating to local communities and helping to combat fuel poverty and resulting negative health impacts.

9. Protecting and creating green space leads to health benefits

Measures on and around NHS sites to protect green space, and enhance biodiversity and the local natural environment can have long-term health benefits for communities. This can include improved mental health and increased biodiversity. Well cared-for green spaces can help to support patient recovery and the health and wellbeing of staff.

Case study: Centre for Sustainable Healthcare’s nature recovery rangers

The Centre for Sustainable Healthcare introduced three nature recovery rangers at NHS sites in Bristol, Liverpool, and West London. Working with NHS partners at Liverpool University Hospitals, Southmead Hospital in Bristol, and Mount Vernon Cancer Centre in London, the rangers have remit to improve the ecological and social value of NHS land, for the benefit of patients, staff, and the wider community.

They run a wide variety of events and eco-projects at their sites, including allotment gardening and food growing, meadow creation, tree planting, woodland conservation, and many other activities that increase biodiversity, encourage nature engagement and support wellbeing.

The initial one-year programme included an evaluation of outcomes, which will provide data on the positive impacts of green space interventions in healthcare settings. More information can be found on the NHS Forest website.

Considerations for making the economic case for investment in climate action

This section sets out some actions to consider in order to strengthen the case for investment in low and zero carbon technologies in your organisation.

1. Consider non-market and unmonetizable benefits in your appraisals

- To fully consider the social and environmental impact of proposals, it is necessary to identify non-market and unmonetizable values.

- The HM Treasury Green Book guidance on appraisals and valuation refers to environmental factors as ‘natural capital’, and considers impacts to life, health and greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions as key non-market impacts.

- Assigning monetary value to these is one approach to ensuring they are given the necessary attention in a typical cost-benefit analysis approach to appraisal. Valuing non-market impacts can help to provide a more reliable picture of when upfront investments in projects will start to pay back, by revealing the hidden environmental benefits of certain actions.

What to consider:

- Key non-market impacts for the NHS to consider for energy-related proposals include quality of life and health, air quality, energy efficiency, GHG emissions, and natural capital.

- Quality of life and health can be valued using quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), whereby the value of one year of life in perfect health is given a monetary value based on willingness-to-pay. Incurred or avoided damage costs can be calculated for changes to air quality using set figures from the DEFRA air quality appraisal guidance. Each type of greenhouse gas has a different cost per tonne of emissions depending on the scale of its impact on public health, the natural environment, and the economy, calculated using modelling. The cost of carbon, in £/t, can be used to determine the cost of avoided GHG emissions for interventions which improve energy efficiency or switch to low-carbon sources of energy. Based on the economic cost of abatement of emissions, carbon prices are projected to increase significantly, highlighting that there is potential to avoid significant damage costs incurred by carbon emissions over the coming years.

This is a strong motivation for NHS trusts to adopt more rigorous energy management and carbon accounting systems to have a clearer idea of their contributions to the estate’s carbon footprint.

The HM Treasury Green Book also encourages natural capital accounting, whereby organisations keep track of their local natural environment and their interactions with it. Having a comprehensive picture of the environments in which they operate will help trusts to identify project proposals and assess their full impact. Furthermore, the consideration of health demographics in local communities is important for trusts to assess how their populations will be affected by climate inaction, and therefore the benefits they may receive from fostering local climate action.

Consider: Identifying social and environmental benefits from projects and calculating the QALYs attributable to them.

2. Whole-life costs

- Considering the whole-life costs of projects or technologies helps to create a more complete picture of their financial payback, in addition to the non-market benefits set out above. Technologies that save carbon will often save money on energy costs too.

- For example, an electric or ultra-low emission vehicle will often have higher purchase or lease costs than a fossil-fuel powered vehicle but would be expected to have reduced running costs. By calculating the likely electric charging costs versus traditional fuel costs, the financial costs for the purchase and the use of this technology can be measured. Maintenance, likely re-sale income, and disposal costs should also be included in whole-life cost calculations, as well as the potential additional costs of installing the infrastructure required to charge electric vehicles. Although many business cases are focused on capital costs, most will also consider financial payback as part of their overall considerations.

- Some investment in low carbon technologies is in addition to costs that would be incurred regardless through business as usual.

- For example, replacing a heating system with a traditional fossil-fuel system will have a significant cost, whilst upgrading a heating system to a low carbon heat pump will often cost more.

- A business case should set out the payback of the additional costs to a project, not the total costs: If a fossil-fuel heating system needs replacing and will cost £X, whilst a heat pump will cost £Y, the justification in a low carbon business case should be in relation to the additional spend, £Y – £X. This is because in both scenarios, the heating must be replaced, so £X would have to be spent either way.

Taking this focus on the additionality of a low carbon spend (rather than total cost) can help to make a financial case stronger when considering the investment in the context of the favourable whole-life costs and non-market and unmonetizable benefits of low-carbon investments.

It is important to ensure that projects follow the four-step programme set out in Figure 1, to ensure that new heating systems are not over-specified, and that heat demand is as low as possible.

Consider: Calculating the whole-life costs of projects and setting out financial paybacks compared to the additional costs for carbon reduction, where appropriate.

3. Engagement and accountability

- Educational campaigns for staff, setting clear individual responsibilities, and embedding accountability for reducing their estates’ carbon footprints are all part of the Estates Net Zero Carbon Delivery Plan. These actions can help to increase buy-in at a senior level and to prioritise interventions which reduce our carbon footprint.

- Furthermore, Greener NHS guidance states that, as part of the NHS legal requirement to meet net zero, all trusts and foundation trusts must have a board-level net zero lead; they can provide support for business case approval.

- The establishment of Integrated Care Systems across England is an opportunity to embed a coordinated and region-specific accountability for reducing the NHS’s carbon footprint, and to ensure that there are clear governance structures in place to drive necessary action.

Accountability at an organisational level can be supported by incorporating climate risk into an organisation’s corporate risk register. Not only will climate change lead to risks to NHS sites from extreme weather events, but failure to systematically reduce carbon emissions now means that there could be higher costs and less time available for meeting increasingly stringent carbon reduction targets in the future. The Delivering a net zero national health service report sets clear targets for carbon reduction, and organisations must plan for how they will meet them. The report also provides evidence of how carbon reduction programmes help to reduce the risks to your organisation from the impacts of climate change.

Consider: Proposing that ‘failure to comply with net zero legal duties and reach NHS carbon reduction targets’ is added as a risk to your board assurance framework.

Case study: Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust risk register

Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust acknowledges the risk to their service provision from a changing climate, and in response to this has taken action to address the problem in two key areas. First, they have included the strategic goal ‘to meet net zero carbon targets to deliver a greener NHS’ in their new trust strategy for 2022-2027, and secondly, they have added the risk on to their board assurance framework (BAF). The risk reads ‘failure to take all the actions within the Green Plan required to contribute to sustainability and the delivery of a greener Notts healthcare’. The BAF captures the controls and assurances that are currently in place to mitigate the risk. It also records a series of actions to address the gaps in controls and assurances which will be undertaken to reduce the risk.

The entry on the BAF ensures that the Board of Directors is aware of the risk and provides assurance that this, along with other risks, is managed effectively. Adding this risk to the BAF is a huge step forward in acknowledging the impact of a changing climate on the trust’s service delivery and will be fundamental to ensuring that the trust is responsive to changing needs and environments. For governance purposes, a lead director and lead committee is allocated to each risk on the BAF, and progress is reviewed quarterly by the board. This ensures that the appropriate action is taken, and levels of assurance are agreed. The trust hopes that this will help them to make the changes necessary to mitigate and adapt to a changing climate and to achieve their strategic goal.

4. Be clear on the costs of inaction

The NHS will need to address the deterioration in public health resulting from the impacts of climate change, and the demand for healthcare that will increase as a result. Air pollution in England is estimated to cost the NHS and social care more than £1.6 billion between 2017-2025. This figure could rise unless significant action is taken to address poor air quality.

Reaching our country’s our country’s ambitions under the Paris Climate Change Agreement could see over 5,700 lives saved every year from improved air quality, 38,000 lives saved every year from a more physically active population and over 100,000 lives saved every year from healthier diets.

Consider: Working within your ICS to identify the public health impacts of climate change locally.

Consider: Support partner organisations within your ICS with the development of their long-term climate change adaptation plan.

5. Costs due to extreme weather and resource shortages

Climate change adaptation is necessary to address resource shortages and extreme weather events which could result in increasing political conflict and cast uncertainty on the future of the UK’s energy security. On-site generation offers a way for NHS organisations to reduce their operational vulnerability. Disruptions in the energy supply chain, resource shortages, and extreme weather could compromise the NHS’ ability to deliver care in the future, compounding the negative impacts of climate change on public health.

There will be direct costs incurred from damage to NHS buildings and the additional energy required to maintain ambient indoor temperatures during extreme hot and cold periods. Patient and staff comfort and safety relies on appropriate temperatures. Adaptive technologies, such as natural cooling and improved building fabric, will reduce the need for energy intensive heating and cooling. Additionally, costs addressing flooding and other extreme weather events are likely to rise along with their frequency. It is therefore essential to build resilience within the physical estate and within energy production and supply.

The Third health and care adaptation report provides an overview of the next steps required at local, regional and national level to address identified risks and build resilience.

Consider: Incorporate climate change impacts into your organisation’s business continuity plan.

Consider: Review the costs to your organisation from extreme weather events.

6. Energy costs

The electrification of heating through the uptake of heat pumps is one of the key ways in which the NHS will reduce the estate’s carbon footprint. To support this, it is essential that we use the energy we have in a more sustainable and efficient manner to avoid increasing spending on energy in the long run. University College London undertook research as part of the Delivering a net zero national health service report, the findings of which were used to support the development of the Estates net zero carbon delivery plan and its accompanying technical annex. If total energy consumption remained at 2019 levels, switching to heat pumps without first reducing energy demand and improving building fabric could increase annual NHS energy bills. To drive overall costs down, NHS organisations must therefore implement measures to reduce consumption, from better energy management systems to LED lighting and changes to space, heating, and ventilation. In addition to on-site generation using solar PV, this could reduce annual energy bills by over £500m as well as significantly reducing the estate’s carbon footprint.