Foreword

This guidance supports the government’s work to reduce suicide and improve mental health services. It promotes a shift towards a more holistic, person-centred approach rather than relying on risk prediction, which is unreliable because suicidal thoughts can change quickly. Instead, it recommends using a method based on understanding each person’s situation and managing their safety.

We ask that all mental health practitioners follow these principles. But guidance alone isn’t enough. Real change requires improvements in training, education, and organisational culture. Many are already adopting this approach, but success depends on collaboration across the entire mental health system, including the NHS, private providers, charities and independent practitioners. This is why we are delighted that many key organisations have endorsed it. This is an area where we need to be open to learn and improve, and where our work is never complete. In the words of lived experience advisors who supported this work:

“Our deepest hope is that these insights will transform how lived experience shapes suicide prevention – from policy creation to frontline care. Every person deserves to feel truly seen and supported in their darkest moments, regardless of their background or circumstances.”

Claire Murdoch, National Director of Mental Health, NHS England

Dr Adrian James, National Medical Director for Mental Health and Neurodiversity, NHS England

Philip Pirie (Co-Chair), Patient and Public Voice

Dr Adrian Whittington (Co-Chair), National Clinical Lead for Psychological Professions, NHS England

Seamus Watson (Programme Lead), National Improvement Director, NHS England

Richard Webb (Lead Writer), Deputy Director of Nursing, Community Mental Health, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust

Philip Pirie dedicates his suicide prevention campaign to the memory of his son Tom.

Introduction

Every day, 17 people die by suicide in the UK. Of those, five are in contact with mental health services, and four of those five (80%) are assessed as ‘low’ or ‘no’ risk at their last contact.

Suicide prediction tools, scales, and stratification (for example, into low, medium, or high risk) are flawed because suicidal impulses are highly changeable and can shift in minutes.

The use of static risk stratification, often based on simplistic questions, is still widespread, but it is unacceptable.

This guidance sets out a replacement approach that puts safety assessment, formulation, management and planning in the context of relational, therapeutic engagement, which is known to improve outcomes.

It supersedes the ‘Assessing and managing risk in mental health services’ guidance issued by the National Mental Health Risk Management Programme in March 2009.

Who should implement this guidance?

The guidance applies to all mental health practitioners in England, working in both community and inpatient settings, and supporting people of all ages.

It should be adopted by public, private and voluntary sector providers, including independent practitioners.

The need for change

The ‘low-risk paradox’ – that most people in contact with mental health services who die by suicide have been assessed as being at low or no risk of suicide – shows that suicide prediction tools, scales, and stratification (for example, into low, medium, or high risk) don’t work. This has been well established by research.

And yet the use of static risk stratification persists. It is supported by myths, including the belief that it minimises liability or standardises care. In some areas, a tick-box culture has developed, using forms and checklists that are unvalidated and have no predictive value.

Both the former Chief Coroner and the Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) have raised concerns about risk prediction and stratification, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence (NG225) emphasises replacing risk prediction methods with a psychosocial approach.

Instead of stratification, practitioners are recommended to explore risks collaboratively, understand changeable safety factors, and co-produce safety plans. Risk is too variable to rely on static categories—it demands nuanced, relational care. NG225 says:

- do not use risk assessment tools and scales to predict future suicide or repetition of self-harm

- do not use risk assessment tools and scales to determine who should and should not be offered treatment or who should be discharged

- do not use global risk stratification into low, medium, or high risk to predict future suicide or repetition of self-harm

- do not use global risk stratification into low, medium, or high risk to determine who should be offered treatment or who should be discharged

- focus the assessment on the person’s needs and how to support their immediate and long-term psychological and physical safety.

- mental health professionals should undertake a risk formulation as part of every psychosocial assessment

This guidance builds on NG225’s approach and removes any uncertainty about what should be done. Practitioners and organisations should eliminate unvalidated and unacceptable practices that have become embedded in the system and replace them with the approaches set out here.

It supports the National Suicide Prevention Strategy (2023), which committed to improving mental health services, and aligns with the Culture of care standards for mental health inpatient services (2024).

Other risks

Practitioners will be following procedures to evaluate and respond to a range of risks (including risk of suicide, risk of neglect or harm from others and risk of harm to others). In doing so, they should be aware that different principles and processes need to be used to manage other types of risk. Practitioners should attend carefully to self-harm as a major risk factor, but management of self-harm more broadly should include other therapeutic approaches not detailed here. Please refer to Psychosocial assessment following self-harm: A clinician’s guide.

The approach: Staying safe from suicide

“Everyone, including me, who feels suicidal needs the system to change. We are people, not just a risk that must be managed.” Lived experience partner.

All mental health care and treatment should be undertaken using a biopsychosocial approach, seeing individuals as having complex physical, emotional and social needs and strengths within a wider relational approach. Attention to safety should be part of the wider approach to mental health care.

This guidance was developed in partnership with over 120 research, clinical and lived experience experts and more than 20 professional organisations. Each section begins with quotes from lived experience partners.

It is underpinned by the research of Professor Nav Kapur and colleagues involved in the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health and an approach to practice set out in the Lancet paper Assessment of suicide risk in mental health practice by Professor Keith Hawton, Dr Karen Lascelles and their coauthors.

Overarching principles

The 10 key principles of the approach are:

- relational safety: build and maintain trusting, collaborative therapeutic relationships. These are the strongest predictor of good clinical outcomes

- biopsychosocial approach: address safety as part of a broad biopsychosocial approach aimed at improving overall well-being by considering biological, psychological and social aspects

- safety assessment and formulation: reach a shared understanding with the individual about safety and changeable factors that may affect this

- safety management and planning: consider the need for immediate action and work with the individual to navigate safety and the factors impacting this over time.

- dynamic understanding: regularly assess and adapt formulations and safety plans based on the individual’s changing needs and circumstances

- evidence-based practice: base work on the latest research and understand population-level risk trends

- involving others: encourage the involvement of trusted others, where possible and as appropriate

- inclusivity: Ensure practices are inclusive and adaptable, particularly for marginalised and high-risk groups

- clear communication: use simple language tailored to the individual and don’t use jargon. Use interpreters or approaches like drawing, if needed

- continuous improvement: regularly review and refine approaches based on outcomes and feedback

These principles apply across all contexts and settings. There will be a variety of ways of implementing the principles and the sections below suggest some recommended methods, but detailed application must be decided by the practitioner according to local policy and professional guidance.

Overview

“I am not just my mental health. There are so many factors that make me who I am but also contribute to what I am going through.” Lived experience partner.

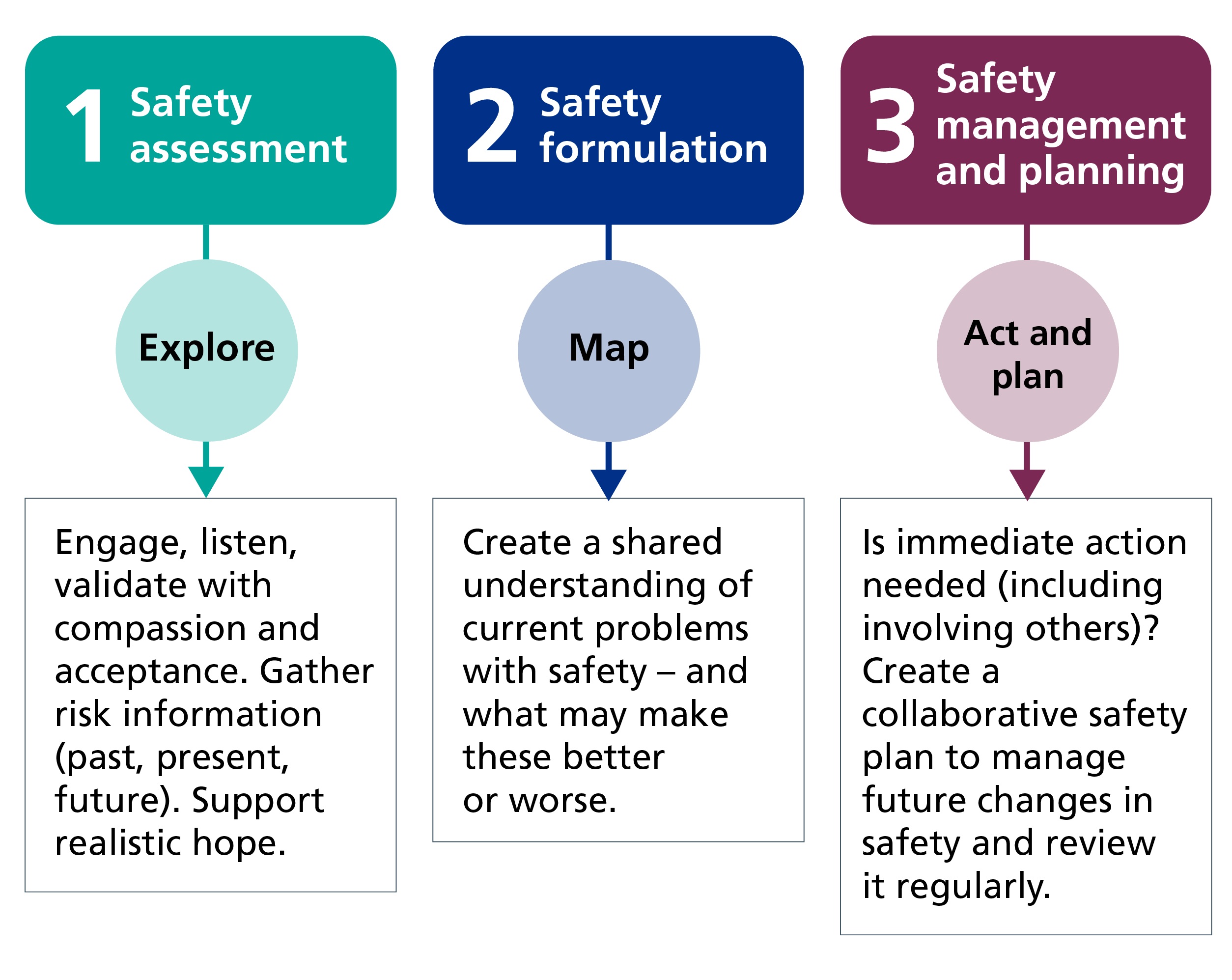

The sections below break down activity into the following 3 elements:

- safety assessment (explore): engage, listen, validate with compassion and acceptance, gather information on past, present and future risks, support realistic hope

- safety formulation (map): create a shared understanding of current problems with safety, and changeable factors that may make these better or worse

- safety management and planning (act and plan): consider if immediate action is needed, including involving others. Develop a collaborative safety plan to help manage future changes in safety. Keep under review

Elements 1 and 2: Safety assessment and formulation

“My son’s suicide risk assessment consisted of three crude questions from a checklist. He was assessed as low risk the day before he took his own life.” Lived experience partner.

Summary

- review past notes: look over any previous relevant information, including safety plans

- have a collaborative conversation: talk openly and sensitively about safety; this can help reduce risk

- explore suicidal impulses: discuss current and past thoughts or actions, noting what increased or reduced risk

- take immediate action: address any urgent safety concerns if required

- identify future risk factors: understand what might increase or decrease risk in the future. Examine biological, psychological, and social influences on safety

- foster realistic hope: acknowledge challenges and feelings of hopelessness while exploring positive steps forward

- develop a safety formulation: build a shared understanding of safety by identifying at least the “Three Ps”:

- presenting problem: What are the current difficulties with staying safe?

- protective factors: What reduces the risk of acting on suicidal impulses?

- precipitating factors: What increases the risk of acting on suicidal impulses?

- next steps: clearly explain what happens next or available options.

- involve trusted others: include family, carers, or others when appropriate.

- review regularly: update the safety assessment and formulation as needed.

Guidance

Biopsychosocial assessment

A biopsychosocial assessment builds a collaborative relationship, gathers relevant information, and fosters realistic hope. This process leads to a shared understanding or formulation of the individual’s challenges and potential solutions, forming the basis of next steps on safety management and care planning.

Building a collaborative relationship

Ensure a warm, empathic approach, creating a safe space where individuals feel supported. Avoid rigid checklists. Instead, use open communication, active listening, and sensitivity to non-verbal communication (for example, body language or eye contact). Be mindful of individual differences, such as how autistic individuals may have sensory sensitivities (for example, to noise or light) and be less likely to express emotions through changes in body language or facial expression. This rapport-building is itself therapeutic and can enhance safety.

Gathering information

Sensitive questioning is essential to uncover suicidal thoughts, intentions, plans, and past behaviours, including what has kept them safe so far. Be mindful that individuals may deny suicidality due to shame or fear. Normalise discussions with statements like, “Many people have thoughts about ending their lives. Is this something you’ve experienced?” Try to discern the meaning of generalisations and metaphors used by the individual such as “there’s not much point any longer”.

Look for warning signs such as researching suicide methods or expressing hopelessness. Explore biological, psychological, and social factors that increase (precipitating factors) or decrease (protective factors) the likelihood of suicidal behaviour.

- precipitating factors: Examples include loneliness, hopelessness, substance effects, gambling harms, physical illness or adverse life circumstances like abuse, financial or relationship difficulties.

- protective factors: Examples include positive relationships, meaningful work, hobbies or special interests, religious beliefs, or physical health.

There is evidence that many people acting on suicidal or self-harm impulses may have no plans or intentions to do so even minutes beforehand. This means it is really important to develop an understanding of factors that may reduce or increase safety for the individual in future.

Supporting realistic hope

Acknowledging feelings of hopelessness and external challenges can pave the way for growth. Practitioners can help individuals take the next step toward support, reducing feelings of entrapment and fostering hope.

Safety formulation

A safety formulation can take many different forms and should be part of a wider understanding of the person’s difficulties. As a minimum, it should include the “3-Ps”.

- presenting problem: What are the current difficulties with staying safe? For example, Jamil has attempted suicide due to feelings of hopelessness after his business failed. He has not ruled out trying again.

- precipitating factors: What increases risk? For example, Jamil is more likely to act on suicidal impulses when he drinks alcohol, has migraines, or has feelings of being a burden.

- protective factors: What reduces risk? For example, Jamil has a close relationship with his brother, finds exercise helpful, and has hopes for a new business venture.

A broader formulation will include two more “Ps”:

- predisposing factors: Relevant longstanding or past factors that underlie current problems. For example, past trauma, diagnosed or undiagnosed autism.

- perpetuating factors: Current stable factors that maintain problems. For example, addictions.

Information sharing and involving others

For children and young people, family or carer involvement is key, barring safeguarding concerns. Adults should decide whether to include trusted others, and consent is required unless immediate risk or legal obligations apply.

Openly discuss who will take action and what steps will follow. Practitioners should clearly communicate available resources and next steps, empowering individuals and their support networks.

Confidentiality and the law

Confidentiality is vital for trust but has clear limits. Practitioners must explain these limits early. Personal information should only be shared if one or more of the following apply:

- informed consent: the individual consents to sharing

- risk of serious harm: there is a risk of serious physical harm or to life

- lack of capacity: an adult lacks capacity under the Mental Capacity Act (2005), and sharing is in their best interests (page 7)

- child safeguarding: a child may be at risk under the Children Act (2004)

- competency concerns: a child lacks ‘competency’ to decide in their best interests

- Mental Health Act: action is required to prevent harm under the Mental Health Act (1983).

In cases of immediate risk to life, the duty to share information overrides confidentiality. If possible, discuss this with the individual.

Consult with colleagues about complex decisions, document all decisions clearly, and refer to the Consensus statement for information sharing and suicide prevention for guidance.

Element 3: Safety management and safety planning

“Work with me to find out who in my network could be a support to me. Please don’t assume who this could be…” Lived experience partner.

Summary

- review safety actions: collaborate to determine if immediate actions are needed to ensure safety

- focus on safety factors: identify and address elements that improve safety and reduce risk

- regularly update: continuously review and adjust the safety plan as needed, monitoring what works

- acknowledge rapid changes: recognise that suicidal thoughts can shift quickly

- involve trusted others: engage family or friends, when possible, for additional support

- co-produce a safety plan: develop a plan with actionable steps, including accessing services and resources

- share the plan: encourage the individual to share their safety plan with trusted people

- integrate into care: make safety planning a key part of the broader therapeutic care plan, empowering individuals to manage crises and work toward stability

Guidance

“My warning signs start with not wanting to leave the house or talk to people, racing mind and suicidal thoughts. This is included in my safety plan, helping me and my family to respond earlier, knowing what to be aware of before a crisis is reached and what to do when we need support.” Lived experience partner.

Safety management

Safety management is a key part of an individual’s wider care plan, which should be built collaboratively and focus on their emotional, social, and physical well-being and engage, where appropriate, with the individual’s family and trusted others. Safety management is a dynamic process that evolves over time and has two components: immediate safety actions and longer-term safety planning.

Key actions for safety management

- immediate safety actions: take urgent actions to ensure safety, if required, such as contacting emergency services or trusted individuals, involving family or carers when appropriate. If necessary, practitioners may breach confidentiality to inform others. They must ensure legal and ethical frameworks guide decisions. In some cases, admission to hospital may be necessary. Explain this sensitively because fear of hospitalisation often prevents individuals from disclosing suicidal feelings.

- longer term safety planning: co-produce detailed safety plans addressing both immediate and future concerns. The planning must be informed by the individual’s unique needs, their support network, and past crises.

Safety planning

Safety plans should help individuals identify warning signs, manage crises, and build support networks. They should be based on the shared understanding developed during the assessment and formulation process and should be written down, reviewed, and shared, as appropriate, with the individual’s family, carers or trusted others. Safety plans can take many forms of which one example is provided below.

Six steps of safety planning, from Stanley and Brown:

- warning signs: recognise thoughts, emotions, or situations that signal a potential crisis (for example, anniversaries, separation, or increased hopelessness)

- coping strategies: identify self-management techniques that have worked before or could be effective in the future

- distraction through connection: plan activities or interactions that help distract from distress, such as visiting a favourite place, engaging in hobbies, or connecting in person or digitally with friends.

- engaging support from others: identify personal contacts (for example, family, carers, trusted adults) to approach when coping strategies aren’t enough. Consider what may be needed and agree this with them. It is important to identify alternative actions if trusted others are not available. Plan how to develop these networks during stable periods

- professional support: include contact details for crisis lines, mental health professionals, or local services. Specify what the individual may need from these professionals at time of contact, including what would be unhelpful

- environment safety: address potential environmental triggers (including online harm) and reduce access to harmful means, like storing or managing medications safely or avoiding high-risk locations

Adaptations

Ensure you recognise where adaptions may be required (for example, learning disabilities, or those with a neurodevelopmental condition such as ADHD or autism) and access appropriate support and resources (for example, the Staying safe from suicide resource hub).

The importance of language in suicide prevention

“Take a trauma-informed approach when talking to me. Tone of voice can make a huge difference when in distress, both positively and negatively. Be warm, gentle and compassionate.” Lived experience partner.

Summary

- adapt your language: use words that suit the individual

- show concern: focus on your concern for their safety, not judgment

- avoid risk labels: don’t describe someone as low, medium or high risk

- use their words: Be curious and reflect the person’s language

- ask open questions: Avoid checklists and closed or leading questions

- use neutral language with families: use simple, neutral language when speaking with family or carers

- confirm understanding: ensure the person understands what you’re saying.

- use respectful terms: say “die by suicide” or “take their own life” not “commit suicide”

Guidance

“I found it difficult to say what I was feeling. Men can find it difficult to talk about their feelings and I needed time to build up trust.” Lived experience partner.

Language shapes thoughts, feelings, and actions. Changing how we talk about suicide is crucial to reducing stigma and encouraging people in distress to seek help and to talk.

Using language that connects

Using open, direct, and appropriate language helps build trust and encourages individuals to share their thoughts without fear of judgment. Discussing suicide openly does not plant the idea in someone’s mind; it often provides relief by signalling it’s okay to talk about it.

When communicating with colleagues, practitioners should express the level of their concern clearly and within a timeframe. For example: “I’m very concerned about their safety today”.

Closed questions, including “Can you keep yourself safe?”, do not help to develop an understanding of the person and often put an unacceptable onus of responsibility on them. Instead, it may be better to ask an open question such as: “What is on your mind at the moment about suicide?” Practitioners may often ask specific questions about suicidal thoughts, intent and plans, but these should only be within a broader exploration. These questions are never enough on their own in assessing suicide risk. Be aware that, at times of great distress, individuals are likely to be less coherent and articulate.

Adopting ‘staying safe’ language

Complete safety isn’t always achievable but practitioners should always aim to provide realistic and supportive engagement. Avoid professional jargon, which can feel impersonal. Instead, stay curious and use the individual’s language to foster openness. Avoid stigmatising terms like “attention-seeking” or “manipulative”, and derogatory references to risk factors such as abuse and gambling. Men, who are three times more likely than women to die by suicide, are more subject to stigma and may see asking for help as a sign of weakness or failure. Don’t take denial of suicidal thoughts or intentions at face value.

Replace “commit suicide” with “die by suicide” or “take their own life.” Use “fatal suicide attempt” or “non-fatal suicide attempt” instead of “successful” or “failed attempt.”

Asking the right questions

Avoid scripted or leading questions like, “You’re not feeling suicidal, are you?” These can create barriers and shift responsibility unfairly onto the individual. Be aware that words like “assessment” may feel judgmental and clarify their intent when necessary. Using checklists in front of individuals is often seen as impersonal and can create a barrier. However, reminders and aides-memoire for the practitioner may be helpful.

Engaging family and support networks

Family and support networks are very often vital in keeping the person safe away from the therapeutic environment. Explore with the individual who is in their trusted network (for example, friends or teachers) and recognise that this can change. When involving family or their network, use simple, neutral language. Remember, this can be an emotional time for these people, too. Avoid breaching trust by contacting others without careful consideration, as it might increase risk if perceived negatively by the individual.

Overcoming barriers to change

Practitioners may feel pressured to provide stratified risk assessments due to expectations from superiors or legal concerns. Remember that risk stratification contradicts NICE guideline NG225 and this guidance and is not acceptable. Use clear language to explain the correct practice to others, emphasising the relational, collaborative approach.

Clear, compassionate language fosters understanding, helps individuals engage with safety plans, and supports follow-up care.

Implementation guidance for organisations

“Suicide prevention demands the courage to listen, to learn and to act. It calls for collaboration across professions, communities and lived experiences to build the foundation of care rooted in empathy and understanding.” Lived experience partner.

Summary

Local actions

- secure senior leadership support, including an executive lead for implementation

- create a detailed implementation strategy with clear timelines

- appoint local champions to drive implementation

- involve service users and stakeholders in the process

- provide training and supervision for all mental health practitioners

- prioritise staff well-being during safety assessments and planning

- align training and education programs with the guidance

- collaborate across disciplines and teams

- update record systems to eliminate risk stratification

- monitor progress (including patient experiences) and evaluate outcomes

- share knowledge, including through the Staying safe from suicide resource hub

National actions

Integrate this guidance into NHS policy, regulation, professional standards, coroners’ expectations, and workforce education and training.

Guidance

All NHS-commissioned services should adopt the principles in this guidance. Private and third sector mental health practitioners are strongly encouraged to follow it, too. Implementation requires action at local and national levels.

Significant work to implement the move away from risk stratification tools is taking place through the inpatient culture of care programme. Any strategies to implement this guidance should connect with the local culture of care programme.

Local implementation

Leadership and strategy:

- support from senior leaders, including trust boards, is essential. Assign an executive lead for implementation

- develop a detailed strategy with clear goals, responsibilities and timelines, aligned with broader initiatives on suicide prevention

Training and practitioner support:

- make training on safety assessment, formulation, and management mandatory

- offer multidisciplinary training sessions to ensure consistent knowledge and integrated working across teams

- support practitioner well-being, recognising the emotional toll of this work and of changes in practice

Systems and tools:

- update electronic record systems to:

- allow narrative input for assessments, formulations, and safety plans

- provide access to past records to avoid service users having to repeat themselves and maintain continuity of care

- move away from outdated risk stratification

Monitoring and learning:

- track progress locally with a focus on:

- implementation within teams

- service users’ and practitioners’ experiences

- collaboration between service users, carers, and professionals

- share lessons learned through regional quality and safety processes

National implementation

Collaboration and feedback:

- incorporate this guidance into all NHS commissioned services, inspections, professional standards and training curriculums

- involve mental health practitioners from the full breadth of professional groups

- patient and public voice groups should contribute to planning and monitoring

- use research and evaluation to monitor outcomes and gather insights from service users and practitioners

- share evidence and examples of successful implementation, including through the Staying Safe from Suicide resource hub

Oversight

Adoption of this guidance will be monitored by bodies such as:

- NHS England and Department of Health and Social Care

- The Care Quality Commission

- coroners

- the Health Services Safety Investigations Body

- the Professional Standards Authority

- professional regulators and insurers

The Health Services Safety Investigations Body (2024) has highlighted the unacceptable use of suicide risk stratification.

The Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care (PSA) is the UK’s regulatory oversight body for people working in health and social care. It requires that the statutory bodies it oversees and non-statutory registering bodies it accredits (accredited registers) have appropriate standards in place for registrants that prioritise patient and service user safety. The PSA supports the adoption of this guidance by practitioners across the public, independent and voluntary sectors. It has committed to reviewing how the guidance can be embedded within its assessments of how the regulators and accredited registers meet its standards.

The Chief Coroner is aware of the need for adherence to this guidance. Individual coroners have a duty to write a ‘Prevention of Future Deaths report’ when they come across practice, which may include non-compliance with this guidance, that gives rise to a risk of future concerns.

Endorsements

These organisations endorse this guidance:

- Association of Child Psychotherapists (ACP)

- Association of Clinical Psychologists UK (ACP-UK)

- Association for Family Therapy and Systemic Practice

- Association of UK Dietitians – Mental Health Specialist Group

- British Association of Art Therapists

- British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP)

- British Association of Dramatherapists

- British Association for Music Therapy (BAMT)

- British Psychological Society

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy

- College of Paramedics

- Health Services Safety Investigations Body

- Mind

- PAPYRUS Prevention of Young Suicide

- Rethink Mental Illness

- Royal College of Nursing

- Royal College of Occupational Therapists

- Royal College of Psychiatrists

- Samaritans

Resources

The Staying safe from suicide resource hub (FutureNHS site; requires log in) includes resources to support practitioners and NHS, private and third sector organisations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the wide range of stakeholders who gave their time and expertise to help produce this guidance. We are especially grateful to those who attended the workshops and those who shared their feedback.

We would also like to thank Hina Sharma, James Roberts and Richard Seager from the NHS England mental health team for their dedication and support in developing this guidance.

Publication reference: PRN01778