Introduction

This document provides guidance to NHS organisations on the management of patients who self-present following exposure to hazardous materials or chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear (CBRN) substances.

This could be the result of an accidental exposure or a deliberate release. Rapid decontamination is identified as the most critical life-saving intervention in all situations.

There are 2 sections:

- Part A provides guidance on the management of self-presenters from incidents involving hazardous materials and is applicable to all health care facilities or NHS branded buildings where patients may present. This includes the initial threat recognition and assessment of patients, along with steps for improvised decontamination (using the ‘remove, remove, remove’ principles).

- Part B is aimed primarily at NHS organisations with type 1 emergency departments and provides additional guidance on the escalation to provide specialist management of contaminated patients. It covers the activation of clinical decontamination facilities, deployment of powered respirator protective suits (PRPS), radiation monitoring, and access to medical countermeasures.

How should you use it?

This document is advisory and intended to support local planning rather than serve as a standalone response plan.

NHS organisations should incorporate these principles into emergency preparedness programmes and review arrangements regularly to ensure compliance with statutory obligations and national standards.

Integrated care boards (ICBs) should also use it to ensure all commissioned services have appropriate and proportionate arrangements in place.

It does not cover ambulance services. All NHS organisations should work collaboratively with all partners and stakeholders to plan and exercise their response to incidents involving hazardous materials or CBRN substances.

1. Background

In recent years there have been a number of high-profile incidents involving hazardous materials: the Eastbourne gas cloud in 2017; Salisbury and Amesbury nerve agent incidents 2018 and a rise in assaults using acidic or caustic substances.

During 2023, around 1,000 incidents involving hazardous substances were reported to UK Health Security Agency, these included a wide range of incidents where individuals had either been exposed to or had the potential to be exposed to dangerous substances (for example, chemical spills at road traffic accidents, incidents involving chemicals on farms or at swimming pools).

In addition to actual exposure, such incidents are likely to result in people presenting to health services who believe that they have been exposed to a hazardous product.

Public concern, confusion and fear can be significant elements of these incidents, and the first indications of a major incident may be the unexpected presentation of casualties to emergency departments and other health care settings. As part of any response, appropriate escalation and communication with system partners is vital.

A range of advice and guidance has been produced in response to this recent history and is referenced in this document. In particular, the ‘remove, remove, remove’ campaign – part of the Initial operational response (IOR) to incidents suspected to involve hazardous substances or CBRN materials (Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Programme [JESIP] 2024) – and the threat recognition tool forms the basis of part A.

Terminology

This document uses the term chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) to describe both accidental and deliberate releases of hazardous substances.

In other sources, you may see the term ‘HazMat’ to refer specifically to accidental or non-weaponised releases, while ‘CBRN’ is reserved for deliberate releases carried out with malicious intent. In this document, these meanings are combined and described under the single term ‘CBRN’.

Organisations should consider the additional implications of a deliberate release. In these situations, they will need to work with the police or security services to support any criminal or forensic investigations

2. Planning

2.1 General principles

Members of the public who may be contaminated, especially following large incidents, may leave the scene and subsequently seek assistance at nearby healthcare facilities or NHS branded buildings. As such, all healthcare facilities and NHS branded buildings where patients might present are required to have arrangements in place to manage self-presenters. These arrangements need to recognise that people concerned about the health impacts of a CBRN incident, but not necessarily affected by it, may also attend even though they do not require medical treatment.

Plans should be prepared in partnership and collaboration with other organisations such as the emergency services, other healthcare providers, the local authority, and voluntary organisations. This is especially important where there are several different organisations located on the same site.

2.2 Related plans

CBRN plans should dovetail with other relevant organisational emergency response arrangements and be developed, in collaboration with partners and relevant stakeholders, to ensure the whole patient pathway is considered. These arrangements should include clear activation of incident response plans and appropriate command and control arrangements that link in with partner organisations to provide/receive mutual aid as needed. The need to control access to hospital site is discussed below and will link to plans for site control and lockdown.

2.3 Risk assessment

A detailed organisational risk assessment should be carried out as part of the planning process to identify local hazards, such as control of major accident hazards (COMAH) sites, industrial premises, and agricultural services. This assessment should be informed by the national, community and local risk registers. This will influence the development of local risk mitigation strategies related to the building environment, staff training and equipment needs.

Operational risk assessments should also take account of the need to protect healthcare facilities, staff members, uncontaminated patients, and other visitors, alongside the provision of timely and appropriate care to people self-presenting from a CBRN incident. These operational risk assessments should give consideration to risks associated with the implementation of local plans and arrangements (annex 4 provides an example template of a CBRN operational risk assessment).

Risks identified should be reported, recorded, monitored, communicated, and escalated in line with organisational risk management policies.

2.4 Premises and cordons

The implementation of local plans will be informed by the nature of the premises used by the service. For the smallest of community-based providers this may simply be the identification of a room where patients can be safely isolated, have privacy to remove clothing and undertake improvised decontamination.

Much more extensive planning will be needed for hospital sites with the ability to set up cordons to establish discreet areas for casualty reception, triage, disrobing, decontamination, active drying, re-robing and treatment. Hospitals will also need to consider how access is maintained for patients who have not been contaminated, how staff can enter and leave the site and how visitors, and/or media are managed.

An incident of this nature has the potential to be disruptive and may result in the affected premises being compromised, so it is important that appropriate business continuity plans are in place and mutual aid.

2.5 Planning for psychosocial impacts

Due to their nature, the psychosocial and mental health impacts of HazMat and CBRN incidents are likely to be heightened and significant. However, early intervention for people at risk, including staff and responders, may reduce their severity and chronicity resulting in more rapidly achieved improved patient outcomes. It is important that response plans take this into consideration.

Children can be particularly vulnerable to adverse psychological reactions during disasters. Staff responding should be mindful of the immediate and long-term effects of these types of incidents on children and do their utmost to keep parent /caregivers together.

Guidance for planning, delivering, and evaluating psychosocial and mental healthcare for people affected by incidents and emergencies, and supporting resources, can be accessed on Resilience Direct (registration required).

2.6 Training and exercising

NHS organisations are required to have an adequate training resource to deliver CBRN training which is aligned to the local CBRN plan and associated risk assessments.

This training should include all staff who are likely to come into contact with potentially contaminated patients and those requiring decontamination. This may include reception or security staff in addition to clinical staff and should be reflected appropriately in training needs analysis.

Staff in acute healthcare settings with emergency departments, where specialist capabilities are maintained to respond to incidents involving CBRN substances, are required to be sufficiently trained to ensure a safe system of work can be implemented in delivering a specialist operational response.

Organisations should also ensure that the exercising of CBRN plans and arrangements are incorporated in the organisations emergency preparedness, resilience and response (EPRR) exercising and testing programme.

2.7 Equipment and supplies

NHS organisations are required to hold appropriate equipment to ensure safe decontamination of patients and protection of staff and an accurate inventory of equipment for decontamination of patients.

In general healthcare settings, the implementation of the ‘remove, remove, remove’ model does not require staff members to wear personal protective equipment (PPE), and equipment should be proportionate with the organisation’s risk assessments.

Acute healthcare settings with emergency departments are required to maintain equipment to support a specialist operational response to incidents involving CBRN substances. This includes clinical decontamination facilities, a minimum provision of specialist PPE, and radiation monitoring equipment. Consideration should be given to the equipment required to manage non-ambulant or collapsed patients. NHS England provides a CBRN equipment checklist which specifies the minimum requirements of equipment that should be available for immediate deployment.

All equipment should be maintained by a preventative programme of maintenance which includes routine checks for maintenance, repair, calibration (where necessary), and replacement of out-of-date items and consumables to ensure equipment is always available to respond to CBRN incidents.

2.8 Access to specialist advice and clinical guidance

In incidents involving contaminated patients it may be necessary to seek specialist advice. Healthcare professionals can access advice and guidance on treatment from the National Poisons Information Service’s TOXBASE (registration required). As previously referenced, clinical staff are also required to have access to the CBRN incidents: clinical management and health protection guidance.

Further operational guidance and advice is available from ambulance services, who have access to further specialist resources.

Further information on the clinical management of a potentially contaminated patient is detailed in the CBRN incidents: clinical management and health protection guidance published by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

2.9 Equalities and health inequalities

NHS organisations have a range of statutory responsibilities with regards to advancing equality and addressing health inequalities. Legal obligations differ depending on the type of organisation and each is accountable for its own planning and subsequent implementation of arrangements to meet its obligations. NHS organisations have a range of statutory responsibilities, including duties under the Equality Act 2010 to eliminate discrimination and advance equality of opportunity, and under the NHS Act 2006 (as amended by the Health and Care Act 2022) to reduce health inequalities in access to and outcomes from healthcare services.

The impact and consequence of incidents and emergencies can present the potential to exacerbate existing or even create new health inequalities. It is therefore vital that organisations ensure the diverse range of local health needs are considered when preparing and responding to incidents involving hazardous materials and CBRN substances.

Challenges to equalities and health inequalities when managing self-presenters from chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear (CBRN) incidents

Experiences from previous incidents and exercises have demonstrated specific challenges associated with implementing arrangements to meet statutory responsibilities regarding equalities and health inequalities when planning for, and responding to, incidents involving hazardous materials and CBRN substances. These experiences demonstrate that to support response arrangements particular consideration should be given to the following issues:

- Dignity – implementation of IOR and decontamination inherently requires the removal of clothing and may have significant implications and requirements for individuals from protected characteristic groups and groups who face inequalities. Arrangements to reduce adverse impacts might include giving consideration to how private screened areas are provided, how groups of different sex and genders might be managed and how the sex and gender of responders might be managed. Clinical decontamination units with multiple decontamination lines can be used flexibly to decontaminate different groups.

- Mobility – IOR focusses on activities that individuals can immediately do for themselves, however this can prove difficult for individuals with physical disabilities and other mobility issues. Clinical decontamination facilities are often fitted with rubber matting, however, wet decontamination inherently makes surrounding areas wet and surfaces slippery which poses a particular challenge to individuals unsteady on their feet. Consideration should be given to how these individuals can be assisted. Can self-presenters assist each other? Emergency departments are also required to have arrangements in place to decontaminate non-ambulant patients.

- Communication – In stressful, busy, and noisy situations, communication can prove challenging at the best of times. This issue can be exacerbated if patients have speech, language, or communications needs. Responders should consider tailoring their instructions to be accessible, inclusive, and actionable by all. This might be assisted using visual/pictorial aids and communication devices, for example, loud hailer.

- Comprehension – individuals with reduced mental capacity or neurodiversity may process information and situations differently. As with communication, responders should consider tailoring their instructions to be understood by all, whilst remembering that vulnerabilities are not always visibly identifiable. These individuals may also require further reassurance and so organisations should consider how this might be supported at a distance. Paediatric casualties should be kept with parents/care givers to assist with life-saving activity and decontamination procedures.

Part A: Initial management of self-presenters

Applicable to all health care facilities or NHS branded buildings where patients may present.

3. Initial operational response

The Initial operational response to incidents suspected to involve hazardous substances or CBRN materials (or IOR 2024) focuses on the activities that the public can immediately do for themselves and actions that responders need to undertake during the initial reporting stages of an incident involving hazardous materials prior to a specialist operational response.

The latest guidance recognises that the cause of the incident, whether deliberate or accidental, is not easily identified at an early stage and does not need to be known for the principles of IOR to be adopted. It includes immediate safety critical considerations, assessment tools, public advice and command and control considerations which are an integral part of the NHS early response to CBRN incidents.

A contaminated person may present at any health care setting or NHS branded building, and it is likely that the first contact with a staff member will not be with a clinician but a member of reception or security staff. As such it is important that these staff, who are likely to have the first contact with a contaminated person, are familiar with this guidance and immediate life- saving activity (see section 4.1 ‘remove, remove, remove’).

4. Initial actions

The initial actions taken following a hazardous substance incident have a significant effect on the outcome for all involved. The following principles will aid first responders:

R – recognise the indicators of a hazardous substance incident.

A – assess the incident to inform an appropriate response strategy.

R – react appropriately to reduce the risk of further harm.

The National CBRN Centre in collaboration with JESIP have produced aide memoirs for the threat recognition tool and associated assessments (CRESS/BADCOLDS) within the IOR which can be utilised by staff to support threat recognition.

A standard operating procedure summarising the care pathway for the initial management of self-presenters can also be found in annex 1.

4.1 ‘Remove, remove, remove’

In the event of an incident where people have been exposed to, or contaminated by, a potentially hazardous substance, the speed of advice communicated to affected people and the first responders is critical to saving lives.

By utilising the ‘remove, remove, remove’ principles, ideally within 15 minutes of contamination, most skin contaminants can be removed, or their effects reduced, thereby helping to reduce further injury or death.

The ‘remove, remove, remove’ principles within the IOR were described initially to manage potentially contaminated persons at the scene of an incident, however they can be adapted as follows for presentation at a healthcare facility or NHS branded building.

If you think someone has been exposed to a hazardous substance, tell those affected to:

1. Remove themselves from the immediate area to avoid exposing others. Fresh air is important.

- isolate person from other patients and staff members

- a safe area, preferably outside, should be identified as ventilation is important

- if skin is itchy or painful find a water source

2. Remove outer clothing if affected by the substance, advise the person to:

- avoid pulling clothing over the head, if possible

- not to eat, drink or smoke

- not to pull off any clothing stuck to the skin

3. Remove the substance from the skin using a dry absorbent material to either soak it up or brush it off, for example blue roll or kitchen towel (see section 5 improvised decontamination)

- rinse continually with water if the skin is itchy or painful

Concerted attempts to maintain patient modesty should be made as far as is practicable, taking into consideration mitigation of hypothermia risks, ethnicity, and gender.

4.2 Isolation/ containment protocol

Once it has been recognised that an incident involving hazardous substances has occurred and initial indications suggest a person has been contaminated, it is important to follow local isolation and containment protocols. Consideration should also be given to the management of multiple services where points of access are collocated at a single reception area.

4.3 Dynamic risk assessment

The information that becomes available following the presentation of a potentially contaminated person should be used to determine the appropriate response level and associated strategies and tactics, including decontamination requirements, medical interventions, and the decision to deploy PPE for IOR.

All decisions made, and actions taken, following a dynamic risk assessment should be recorded, including the rationale behind them. Organisations may wish to develop tools to support dynamic risk assessments and decision making, such as flow charts.

4.4 Alerting and escalation

Timely alerting and escalation of the incident is essential. Incidents should be escalated in line with local procedures in order to access timely support and advice.

If a potentially contaminated person presents at any facility that does not have an emergency department, then the emergency services should be alerted via 999. Staff should be prepared to provide emergency services with a M/ETHANE report in order to develop shared situational awareness and enable a safer IOR.

Depending on the severity and duration of the incident it may be appropriate for the affected organisation to enact its incident response arrangements. Triggers for this should be included in plans.

4.5 Management of personal belongings

When instructed to remove outer clothing or disrobe, the patients should be provided with plastic bags for clothes and smaller plastic bags for other personal effects. All personal belongings should remain in a designated area ideally outside.

These items are surrendered with a view to either being destroyed if the contaminant is deemed at a hazardous level, or are seized by the police as forensic evidence in the event of a deliberate release.

Specialist advice should be sought to determine whether an unknown contaminant is non-hazardous and subsequently deemed to be a very low risk (or nil hazardous risk) in order that the property may be returned to the patient when appropriate.

4.6 Staff safety

It may not be possible to carry out a full patient assessment during IOR. Under no circumstances should staff be further exposed to known or suspected hazardous substances in order to obtain information.

The principle to be followed by staff is that direct physical contact with the patient(s) should be avoided with the focus on isolating patients, escalating for urgent assistance, and following the principles of ‘remove, remove, remove’.

Where PPE is available, the IOR may be augmented by the use of standard infection prevention and control (IPC) precautions in line with a local risk assessment.

5. Improvised decontamination

5.1 Dry decontamination

Dry decontamination is the default intervention for anyone that is suspected of being contaminated during a chemical incident, unless there are obvious signs of burning, skin irritation or the contaminant is known to be either biological or radiological materials.

Dry decontamination is the use of any available dry absorbent material, such as paper tissue or cloth, applied to the affected body surface to soak up or brush off as much of the contaminant as possible.

Fresh dry materials should be provided throughout the decontamination process and not passed from one person to another. When conducting dry decontamination, a separate piece of clean material should be used for each area of the body that may have been contaminated. Contaminated persons should be instructed to:

- Blot and wipe their hands first.

- Blot and wipe their hair.

- Blow their nose.

- Blot and wipe their face and neck. Wipe any chemicals away from their eyes and mouth.

- Blot and wipe their left shoulder and arm and then repeat for their right shoulder and arm.

- Blot and wipe their chest, stomach and back.

- Blot and wipe their left leg and foot and then repeat for their right leg and foot.

- Help anyone who requires assistance by blotting their hair and skin from the top down.

Combined with ‘remove, remove, remove’ protocols, dry decontamination alone can be effective at removing contaminants. However, whether wet decontamination follows dry decontamination should be the subject of a dynamic risk assessment, as the nature and extent of contamination will be context specific and may be informed by specialist advice (see section 2.8 access to specialist advice).

Wet decontamination may be needed to decontaminate hair, or to provide reassurance to affected persons and staff following dry decontamination.

5.2 Wet decontamination

Wet decontamination should be used if contamination with a caustic chemical substance is suspected, or if the contaminant is known to be either a biological or radiological agent. Improvised wet decontamination is the use of copious amounts of water from any available source (such as taps, showers, hose-reels, sprinklers, water bottles etc.) to dilute and flush the contaminant away from the body surface.

Where water is not available, wet wipes/baby wipes can be used as an alternative as they are effective in removing contaminants and are easier to control in terms of waste.

All reasonable steps should be taken to contain contaminated waste water. In all circumstances the Environment Agency should be notified at the earliest opportunity and ideally in advance of the initiation of wet decontamination without delaying lifesaving activity. The Environment Agency is able to provide advice and guidance with regards to the protection and monitoring of water courses and management and disposal of waste.

Improvised decontamination should continue until structured interventions, such as interim or clinical decontamination, becomes available either once emergency services arrive on site or once the clinical decontamination facilities are prepared in acute settings with emergency departments, or until such time immediate scientific advice determines otherwise.

Wet decontamination and the use of water can exacerbate the risk of hypothermia, particularly during periods of cold weather. As such considerations should be given to mitigate this in line with dynamic risk assessments.

6. Consolidating the response

If a potentially contaminated patient presents at any facility that does not have an emergency department, then the emergency services should be alerted via 999.

It’s important that information gathered at the point of presentation, such as within the initial M/ETHANE report, and as part of the recognition and assessment is relayed effectively to call handlers and control rooms. This should be done concurrently with implementation of IOR.

NHS ambulance services maintain hazardous area response team (HART) and specialist operational response team (SORT) capabilities in line with interoperability specifications. This includes the ability to facilitate the wet decontamination of individuals affected by CBRN incidents.

Fire and rescue services (FRS) also maintain a capability to deploy interim decontamination arrangements, for example, ‘ladder pipe’ system, and technical mass decontamination units for ambulant patients.

In acute healthcare settings with emergency departments, hospital sites are required to maintain clinical decontamination facilities via either inflatable mobile, rigid frame/cantilever, or built/static decontamination structures. The implementation of IOR should be done concurrently to the preparation of these clinical decontamination facilities.

The capability of emergency services to undertake improvised or clinical decontamination is limited and resources may already be committed/required at the scene of an incident, and therefore not an alternative to, or replacement for, adequate NHS planning and response.

Part B: Specialist management of contaminated patients

Applicable to acute settings with emergency departments and clinical decontamination facilities.

7. Specialist operational response

Acute health care settings with emergency departments are required to maintain specialist capabilities to respond to incidents involving hazardous materials or CBRN substances which constitute a specialist operational response. These include clinical decontamination equipment, specialist personal protective equipment (PPE), radiation monitoring equipment and access to medical countermeasures.

In addition, and often in parallel to providing immediate lifesaving activity as part of the IOR, acute health care settings should have procedures in place to activate a specialist operational response.

The decision to activate these procedures may be taken on the outcome of a dynamic risk assessment as described in part A, if the contaminant is unknown and requires wet decontamination, or a patient requires close personal support requiring specialist PPE, for example, following the collapse of a previously ambulant contaminated patient.

In the event that a specialist operational response is deployed, organisations retain their legal duty of care towards its employees and are responsible for implementing safe systems of work.

Ambulance service CBRN support to acute trusts

NHS ambulance trusts must support designated acute trusts (hospitals) in preparedness activities to maintain CBRN/HazMat tactical capabilities.

The support provided by NHS ambulance services must include, as a minimum, a biennial (once every 2 years) review of the hospitals CBRN decontamination capability and the provision of training support in accordance with the provisions set out in the NHS core standards for EPRR.

7.1 Activation

In the event that a specialist operational response is determined as necessary, and proportionate, the response should be activated by the operational commander in the department (for example, emergency department (ED) nurse in charge/ ED consultant).

Organisations should be prepared to deploy, and operationalise, clinical decontamination equipment and establish safe systems of work ready to receive patients as quickly as possible.

7.2 Disrobing

The process of disrobing is highly effective at reducing the effect of hazardous materials and CBRN substances when performed as soon as possible after exposure, ideally within 15 minutes. If disrobing is followed immediately by effective decontamination as appropriate, research has shown that staff can be confident of removing most skin contaminants.

Therefore, if not undertaken following evacuation from a contaminated area, or as part of initial management of a self-presenter, disrobing at least to underwear should be considered the primary action.

Undressing should be as systematic and consistent as is practicable to avoid transferring any contamination from clothing to the skin, airway, or peripheral open wounds. Patients should avoid pulling clothing over the head if possible. This may require the use of scissors or shears to cut clothing off.

Concerted attempts to maintain patient modesty should be made as far as is practicable, taking into consideration mitigation of hypothermia risks, ethnicity, and gender.

As previously referenced, patients should be provided with plastic bags for clothes and smaller plastic bags for other personal effects that should remain in a designated area outside of the emergency department.

7.3 Dynamic risk assessment

As with the IOR and in-line with the Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Programme (JESIP) principles, dynamic risk assessments should be used to determine the appropriate response level and associated strategies and tactics during the specialist management of self-presenters. For example:

- the requirement to undertake clinical decontamination following improvised decontamination

- the need to repeat decontamination protocols

- the number of staff deployed in powered respirator protective suits (PRPS)

- levels of staff PPE required following decontamination during definitive care

All decisions made, and actions taken, following a dynamic risk assessment should be recorded, including the rationale behind them.

8. Powered respirator protective suits

Powered respirator protective suits (PRPS) are the primary personal protective equipment (PPE) used by both ambulance services and acute NHS trusts in the event of the need to undertake clinical decontamination of patients from CBRN incidents.

In order to ensure maximum decontamination capability is maintained across the NHS in England, NHS England have determined that ambulance trusts and acute health care settings with type 1 emergency departments are required to maintain PRPS stock levels as follows:

- acute trust emergency departments to have 24 suits

- ambulance trusts to have 240 suits

These numbers aim to ensure an appropriate mix of different sized suits across the stock held by the site or service to allow for a diverse workforce of different builds and sizes to be sufficiently equipped. For emergency departments this provision is expected to provide enough suits to begin clinical decontamination of self-presenters and cover the first 6 hours of a response to a reasonable worst case scenario event.

Organisations are reminded that in line with PPE at Work Regulations 2022 (PPER 2022), employers must ensure their workers have sufficient information, instruction, and training on the use of PPE. This includes the use of PRPS which should only be used by trained and competent personnel. Further information on the duties and responsibilities of employers under PPER 2022 can be found on the Health and Safety Executive website.

8.1 Powered respirator protective suits (PRPS) deployment

Once a decision has been made to deploy staff in PRPS, a predetermined member of staff should be designated as an entry control officer (ECO). The ECO is responsible for supporting donning procedures of operatives to be deployed in PRPS, confirm a rescue team is on standby, record entry time of deployed PRPS team and monitor elapsed time of each operative.

A minimum of 2 PRPS responders should be deployed utilising a buddy system to maintain a safe system of work. Whilst working in PRPS, responders should maintain contact and communication with their buddy and other team members, including the ECO, at all times. PRPS maximum wear time is 60 minutes, followed by 15 minutes suit decontamination time. PRPS responders should be ready for suit decontamination prior to the end of the maximum wear time.

Donning and doffing procedures should be followed in line with nationally approved training materials and manufacturer’s instructions.

8.2 Emergency rescue plan

In addition to operational staff deployed in PRPS, a minimum of 2 further PRPS operators should also be on-standby ready to deploy at all times in order to maintain safe systems of work. It’s recommended that these operators are suited up to the waist ready to complete donning of PRPS once a rescue plan has been activated by the ECO.

Standby PRPS operatives are to deploy in response to the recovery of a staff member, already deployed in PRPS, who is experiencing difficulties, or to support existing staff already deployed in PRPS to manage collapsed, non-ambulant or vulnerable patients.

Operatives should approach the downed operative/patient if safe to do so and place the patient into the recovery position. Whilst transfer boards and stretchers are being prepared, immediate life-saving actions in line with the IOR should be undertaken if not already done, ie removal of patient’s clothing. Implements such as tuff cut scissors will need to be utilised by the rescue team to carry out an emergency disrobe of a downed PRPS operative.

Once transferred to a stretcher the patient should be decontaminated in line with protocol for non-ambulant casualties.

The number of additional PRPS operatives required to support the rescue/retrieval will be dependent on the ECO’s dynamic risk assessment which will take into account the weight of the patient/downed operative and the terrain that will need to be negotiated by the rescue team.

Once standby staff have been deployed, these standby roles should be backfilled in order to maintain safe systems of work.

8.3 Powered respirator protective suits (PRPS) resupply

In the event an acute emergency department falls below the number of suits required to provide a safe system of work and requires additional suits in response to an incident, the organisation should contact their local NHS ambulance service in the first instance to arrange a temporary loan.

Local integrated care boards should be notified of incidents requiring the redeployment of suits at the earliest opportunity in order that they are on standby to support the coordination of a resupply.

If further stock is required during an incident, organisations should make contact with NHS England regional EPRR teams who can coordinate mutual aid arrangements between ambulance services, or resupply from the national stockpile maintained by the NHS Resilience Emergency Capabilities Unit.

9. Clinical decontamination

9.1 Clinical decontamination facilities

Clinical decontamination is the process where contaminated persons are treated individually by trained healthcare professionals using purpose designed decontamination equipment.

Health Building Note (HBN) 15-01 requires acute health care settings with emergency departments to give consideration for the need to accommodate decontamination rooms within the department. The HBN also requires consideration be given to the ability to meet the sudden rapid increase in numbers of patients arriving when a CBRN incident occurs.

Decontamination facilities can be enhanced by demountable clinical decontamination units, such as temporary inflatable or rigid/cantilever structures, which require assembly before use; or more permanent structures such as static clinical decontamination units.

Regardless of unit type, organisations must have the ability to deploy these units immediately and operationalise as quickly as possible from the point of determining the requirement for wet decontamination.

9.2 Decontamination prioritisation

Depending on the number of self-presenters a triage trained nurse may need to undertake primary triage of those requiring decontamination to determine order of priority. The triage nurse should avoid direct physical contact where possible in order not to further expose themselves to known or suspected hazardous materials. However, it may be considered necessary to deploy a forward triage officer in PRPS if required.

Whilst there is no standardised CBRN triage tool, the Major incident Triage Tool or Ten second triage tool can be used to determine clinical priority. However, monitoring signs and symptoms of contaminated patients may also be taken into consideration, particularly respiratory and circulatory signs and symptoms, as part of a more thorough assessment.

When dealing with paediatric cases, the primary triage tools used for adults can also be utilised by emergency department staff. However, due to their unique physiology, children can often compensate for significant clinical illness and may not exhibit signs of distress until they are seriously ill. When compensatory mechanisms in children fail, they tend to do so rapidly. This underscores the need for vigilant monitoring of signs and symptoms, warranting a higher index of suspicion.

Any patients whose clinical decontamination has been deferred following triage should be instructed to undertake immediate lifesaving activity in line with the IOR principles including ‘remove, remove, remove’ and improvised dry/wet decontamination if not already done so.

Where possible, and in keeping with optimal decontamination principles, all attempts should be made to avoid unnecessary bottlenecks. As such, consideration should also be given to available resource and efficient utilisation of decontamination facilities, particularly where separate facilities for decontamination of non-ambulant patients are available.

9.3 Decontamination protocol

Current research suggests the duration of decontamination should be limited to between 45 -90 seconds. This is to limit any adverse effects associated with the use of water as a decontamination medium, particularly where the contaminant is unknown, minimise the risk of a ‘wash in’ effect causing increased dermal absorption, and maximise throughput of patients requiring clinical decontamination where there may be multiple patients.

Other optimised parameters for clinical decontamination, determined through a series of studies under the Optimisation through Research of Chemical Incident Decontamination Systems (ORCHIDS) projects, include a shower water temperature of 35-40 degrees centigrade; provision of washing implements, including sponges and/or wash cloths; and use of dilute (neutral) detergents.

The rinse-wipe-rinse approach is recommended. Patients should be instructed to:

1. Rinse – wash with water from top downwards to remove any particle and water-based chemicals.

2. Wipe – using sponges/wash cloths and dilute neutral detergents, wipe affected areas to remove organic chemicals and petrochemicals that might adhere to skin.

3. Rinse – with clean water to remove detergent and any residual chemicals.

As mentioned, this process should take no longer than 90 seconds, however, if contamination remains obvious, repeat steps 1 to 3, aligned to a dynamic risk assessment, ensuring the patient is as clean as is reasonably practicable whilst avoiding further dermal abrasion that may result in broken skin and provide an entry point for contamination.

9.4 Decontamination protocol for non-ambulant patients

Decontamination of a non-ambulant patient should take 5 minutes. This protocol applies to casualties who have been cut out/disrobed in IOR or in line with dry cut out protocols and incorporates stretcher decontamination requiring a minimum of 4 PRPS operative roles.

1. Rinse – spray water on all front surfaces ensuring airway is protected at all times.

2. Wipe – wash front of casualty with sponge including face and hair, upper body, arms and hands, lower torso, legs and feet.

3. Rinse – spray water on all front surfaces ensuring airway is protected at all times.

4. Turn and rinse – roll casualty onto their right-hand side – rinse all rear surfaces.

5. Wipe – wash back of casualty with sponge.

6. Rinse – spray water on all rear surfaces.

7. Turn and exit – roll casualty back to supine position.

If contamination remains obvious repeat steps 1 to 7, aligned to a dynamic risk assessment, ensuring the patient is as clean as is reasonably practicable whilst avoiding further dermal abrasion of the skin.

Once clinical decontamination is completed the patient should be transferred to the active drying area to be towel dried

9.5 Active drying

Active drying is also a key step in removing contaminants from the skin surface. Clean towels or other suitable drying materials for each patient should be made available following wet decontamination and included in plans. Used towels should be treated as contaminated waste and remain in the active drying area.

9.6 Re-robing

Following clinical decontamination and active drying, casualties will need to be provided with suitable garments to provide modesty, warmth and clinical wellbeing before transferring the patient into the emergency department.

9.7 Post-decontamination procedures

It may not be possible to guarantee that a patient is totally decontaminated at the end of this procedure. However, research shows that disrobing followed by dry and/or clinical decontamination provides a 10-fold reduction in contamination and sufficient dilution of a contaminating agent.

Once a patient has undergone clinical decontamination, they may be considered safe to enter the emergency department with caution and treated as appropriate to their condition. Standard infection prevention and control (IPC) precautions should be adhered to with suitable PPE determined and implemented in line with a dynamic risk assessment, especially where the contaminant remains unknown.

Any contaminated water should be retained and secured in appropriate wastewater collection bladders, vessels, or tanks. Arrangements for disposal should be made for specialist wastewater provider collection either via the trust waste manager or activation of any prearranged contracts.

Depending on the contaminant, a dynamic and proportionate approach should be taken to the cleaning of the clinical decontamination unit to return it to a state of readiness based on specialist advice. This may require the services of a third-party specialist cleaning contractor or in extreme circumstances, replacement of the entire unit.

Ensure all sundry items and specialist equipment is replaced as quickly as possible in order to maintain CBRN capabilities in a state of readiness to mitigate any potential late presenters or further incidents.

9.8 Onward triage

Following clinical decontamination and depending on the number self-presenters in addition to any casualties being brought to the emergency department from the scene of the incident by ambulance services, it may be necessary for emergency department triage to be undertaken.

The purpose of triage is to identify patients in need of life saving intervention, prioritise intervention and suggest the interventions required. Further information on emergency department triage can be found in the Clinical guidelines for major incidents and mass casualty events

9.9 PRPS decontamination

Decontamination of PRPS is necessary before the wearer can disrobe from the suit and report back to the ECO and should take place once the PRPS operative’s tasks are completed or once 60 minutes of work period has elapsed (whichever is sooner); or where there has been an evacuation from the dirty/decontamination zone.

PRPS decontamination procedures should take place in a predesignated decontamination area, often the clinical decontamination unit, which should be staffed by a decontamination officer.

Effective decontamination should be performed in a 3-phase buddy system and last 12 minutes in line with training materials. The decontamination officer will guide wearers and monitor timings. Once decontaminated the wearer will step in to the disrobing area where a clean zone operative wearing suitable PPE will assist them to disrobe. The clean zone operative should be trained in the use of PRPS with knowledge of the disrobing procedure to ensure the used PRPS is safely removed and securely contained within the Tyvek bag provided.

10 Radiation monitoring

Following the implementation of IOR principles, the management of patients potentially contaminated with radioactive materials differs from the advice where chemical or biological contaminants may be involved. A person exposed to radiation is no risk to health workers once removed from the source. However, contamination with radioactive materials may pose a risk. As such, in incidents where a radioactive contaminant is suspected, patient screening with handheld monitors is required.

Critically ill or seriously injured (P1) patients must not have life and/or limb saving treatment delayed by decontamination. Therefore, it is important to consider and plan for how these patients would receive life and/or limb saving treatment within an emergency department before decontamination.

10.1 Personnel

In the event of an incident involving patients potentially contaminated with radioactive materials, response teams should be supported in addition to the clinical care team by:

- radiation protection advisor (RPA) – role to be filled and predetermined in organisational response plans by personnel with knowledge of radioactive protection. This may include medical physicists; nuclear medicine physicians; radiologists, radiation oncologists etc

- RAM GENE operators – a minimum of 2 appropriately trained persons familiar with the use of handheld instruments (RAM GENE) to perform the radiation contamination survey

10.2 Protecting staff from radioactive contamination

Staff will be protected from radioactive contamination by using standard IPC precautions and advised to follow the same procedures as those used to deal with human blood or body fluids when handling patients potentially contaminated with radioactive materials.

PPE should include as a minimum:

- simple respiratory protection (must be fit tested – FFP3 rating recommended)

- surgical gloves (must be changed frequently)

- waterproof coveralls

- waterproof overshoes or boots

- hair cover (surgical cap)

- eye protection devices

Depending on the nature of the incident, or contaminant, the RPA will be able to advise if further precautions are necessary.

Whilst standard IPC precautions provide sufficient protection against cross contamination from radioactive substances, it does not provide protection against penetrating radiation (Gamma/X-ray or neutron radiation). Cases of contamination that give rise to dangerous levels of penetrating radiation is likely to be extreme and in very small numbers. This risk is managed by controlling exposure time through timely screening, initial dose rate screening from a distance, the use of personal dosimetry equipment and subsequent decontamination of contaminated cases.

The RPA should issue personal dosimetry equipment to person’s directly involved in the screening of patients, and the removal and storage of radioactive shrapnel. Emergency departments may stock these in line with local risk assessments. However, where personal dosimeters are limited:

- access additional devices from other departments of the hospital which routinely deal with radiation. This should be predetermined in organisational plans

- consider using a dosimeter as a ‘sentinel’ dosimeter, the results of which can be used later to provide estimates of individual staff doses based on staff occupancy times

10.3 RAM GENE

A RAM GENE radiation contamination meter is designed to detect surface radiation contamination and any subsequent requirement for decontamination. NHS England have determined that emergency departments are required to test and maintain a minimum of 2 units although local risk assessments may identify the requirement to maintain additional units.

10.4 Radiation contamination survey protocol

All patients who present to the emergency department with either suspected external radioactive contamination or ingested radioactive material should under-go clinical decontamination prior to a radiation contamination survey.

The survey will be undertaken by 2 staff members who have successfully completed training to perform the radiation contamination survey with a RAM GENE 1 radiation monitor. Before conducting the survey, these staff members will be required to inspect the equipment, perform a battery check, conduct a function check and a background reading.

During the contamination survey, survey staff will firstly use the monitor in the dose-rate mode (cap on) to perform a careful scan of the patient’s body, no closer than 30cms from the body surface, lasting approximately 30 seconds.

If the dose rate rises above 1 μSv/h, this is a positive reading, and the patient should be considered contaminated. If not already done so, the patient should be instructed to fully disrobe. Patients clothing should be bagged and sealed.

Once the patient has disrobed, the radiation monitor should be set to contamination mode (cap off). Survey staff will perform a detailed scan for external contamination, scanning the body slowly at a distance of about 1cm. The full scan should take at least 3 minutes.

Where the count-rate rises above 300 cps then the presence of contamination is confirmed. Identify these contaminated areas on a monitoring/contamination report form and record the measured count-rates. Direct the clinical team to remove contamination from the patient in the following order of priority:

- wounds

- airways

- remaining body surface

Any identifiable fragments of materials are to be handled with 6” forceps and placed in a clear plastic specimen container and be retained for analysis. This should be labelled and stored in a shielded area away from the monitoring location. The RPA will be able to advise on the safe management of removed shrapnel and specimens.

Repeat the detailed scan for external contamination and in areas where the count-rate remains above 300 cps repeat local decontamination measures. Record changes in the measured count-rates following decontamination process. Decontamination procedures for external radioactive contamination should be stopped after 2 decontamination cycles to lower the risk of skin damage. In any case, external decontamination should not continue if signs of skin irritation appear since damage to the skin barrier can increase the risk of internal contamination.

Where external contamination is below 300 cps, precautions necessary for the management of radioactive contamination can be discontinued. The patient can then be transferred to a clinical area for treatment.

11. Countermeasures/treatment

CBRN countermeasures are medicines held in central stockpiles to mitigate the impact of and protect and treat the public should they be exposed to any hazardous materials released during a CBRN incident. Any provider organisation with an emergency department or other suitable emergency treatment centre, having sought relevant specialist advice, may request that countermeasures are delivered to support the management of patients arriving with symptoms following exposure and who will, following assessment, benefit from countermeasures. Countermeasures are accessed via escalation to NHS England and supplied within a short timeframe in 2 ways:

- chemical countermeasures supplied via NHS Blood and Transplant and will usually be sent to an emergency department

- biological, radiological and nuclear countermeasures are dispatched by the United Kingdom Health Security Agency (UKHSA) appointed holder and delivered to organisations goods receiving or pharmacy departments

Provider organisations are responsible for ensuring arrangements are in place for requesting, receiving and onward distribution of any countermeasures requested. Further guidance on accessing countermeasures can be accessed on Resilience Direct.

12. Consideration for recovery

12.1 Waste disposal

In the event of contamination with hazardous materials, staff will ensure that all non-sharps contaminated materials, including used PPE (not PRPS), is disposed of in double clinical waste bags, secured, labelled and stored securely in an external environment. Any sharps containers that are contaminated will be quarantined with the other double bagged waste. Special arrangements are required for radioactive material/clinical waste. Staff will seek advice from an appropriate radiation protection adviser.

12.2 Wastewater management

Provider organisations have a duty to ensure that contaminated wastewater is managed appropriately, recovered, or disposed of safely, that it does not cause harm to human health or pollution of the environment, and is only transferred by authorised persons.

As previously mentioned, arrangements should be made for specialist wastewater provider collection either via the trust waste manager or activation of any prearranged contracts. The Environment Agency must be contacted if any contaminated wastewater is lost to normal drains.

12.3 Decontamination of contaminated areas

If an area is contaminated it will not be reopened until advised that it is safe to do so. This may follow decontamination. Advice could be sought from the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), the UKHSA and Fire and Rescue Service (FRS) Detection, Identification and Monitoring (DIM) team as required. In the case of radioactive contamination, advice should be sought from an appropriate radiation protection adviser.

12.4 Recertification of powered respirator protective suits (PRPS)

Following the decontamination of PRPS, and as part of doffing procedures, suits should be bagged up and sealed in the Tyvek bag provided with a label which includes the users name, the suit number, incident reference and date.

Organisations should notify the NHS Resilience Emergency Capabilities Unit (NRECU) PRPS coordinator by email (england.prps@nhs.net) of any operational suits that have been deployed, in order to support the recertification of used suits. The manufacturer will issue a returns form for completion by the organisation, requesting information with reference to the incident in order to determine whether a suit is “safe to handle” based on the information provided.

Once the manufacturer has confirmed that it is safe to handle, suits should be dried and returned to their boxes and packed carefully to ensure visors do not become damaged. Suits are then returned to the manufacturer for recertification.

If the manufacturer is unable to confirm that the suit is safe to handle, either due to the particular contaminant, a failed servicing or a lack of complete information provided, organisations will be required to purchase replacement suits in order to maintain PRPS stock levels.

If there are any issues or delays to purchasing replacement suits resulting in Trust’s falling below recommended minimum requirements of operational suits, the NRECU PRPS coordinator should be notified. NRECU have access to a national reserve stock and whilst this is limited in numbers, it may be considered for the loan of short-term replacements where it is deemed appropriate and necessary.

13. Implementation

Local implementation of this publication should be considered as part of annual emergency preparedness, resilience and response (EPRR) work programmes. To ensure arrangements are kept up to date, NHS-funded organisations should update their emergency plans in line with current national guidance as part of a routine review. However, category 1 responders are also required to consider whether the publication of guidance significantly affects local risk assessments which makes it necessary or expedient to revise plans sooner. As a minimum this should be completed within 12 months of the plan’s last review. It is good practice to follow a standard cycle of plan maintenance activities.

14. Appendices

14.1 Annex 1: Initial management of self-presenter care pathway standard operating procedure

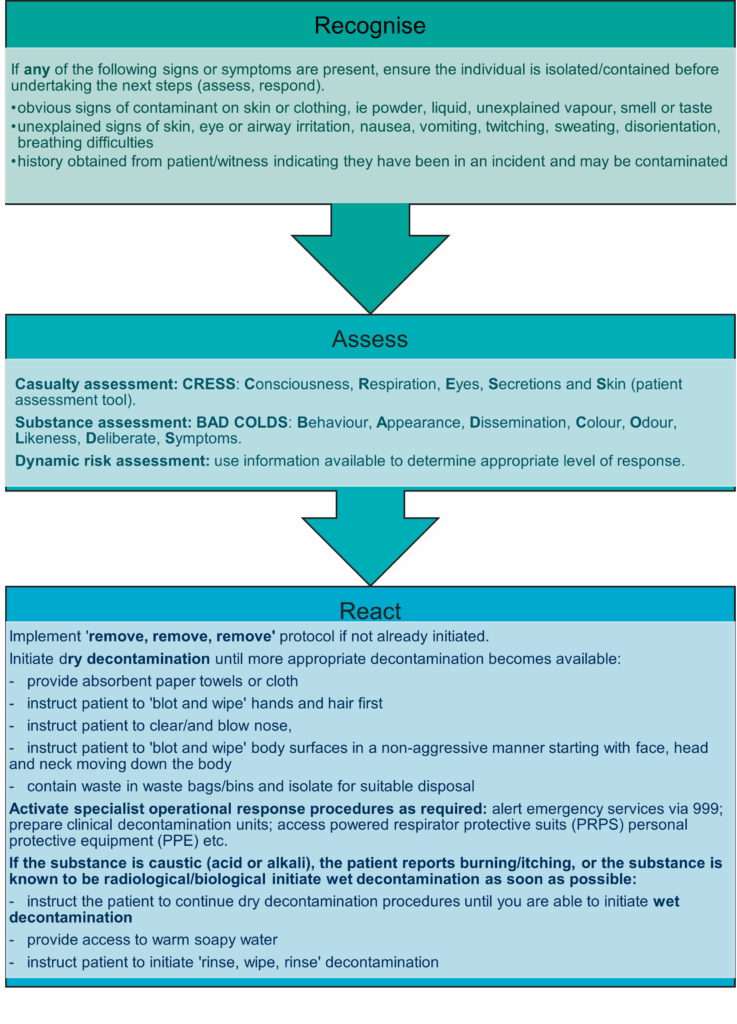

The flowchart above sets out the initial management of the self-presenter care pathway standard operating procedure, including ‘recognise’, ‘assess’ and ‘react’

Recognise

If any of the following signs or symptoms are present, ensure the individual is isolated/contained before undertaking the next steps (assess, respond).

- obvious signs of contaminant on skin or clothing, ie powder, liquid, unexplained vapour, smell or taste

- unexplained signs of skin, eye or airway irritation, nausea, vomiting, twitching, sweating, disorientation, breathing difficulties

- history obtained from patient/witness indicating they have been in an incident and may be contaminate

Assess

- Casualty assessment: CRESS: Consciousness, Respiration, Eyes, Secretions and Skin (patient assessment tool).

- Substance assessment: BAD COLDS: Behaviour, Appearance, Dissemination, Colour, Odour, Likeness, Deliberate, Symptoms.

- Dynamic risk assessment: use information available to determine appropriate level of response.

React

Implement ‘remove, remove, remove’ protocol if not already initiated.

Initiate dry decontamination until more appropriate decontamination becomes available:

- provide absorbent paper towels or cloth

- instruct patient to ‘blot and wipe’ hands and hair first

- instruct patient to clear/and blow nose

- instruct patient to ‘blot and wipe’ body surfaces in a non-aggressive manner starting with face, head and neck moving down the body

- contain waste in waste bags/bins and isolate for suitable disposal

Activate specialist operational response procedures as required:

- alert emergency services via 999

- prepare clinical decontamination units

- access powered respirator protective suits (PRPS) personal protective equipment (PPE) etc.

If the substance is caustic (acid or alkali), the patient reports burning/itching, or the substance is known to be radiological/biological initiate wet decontamination as soon as possible:

- instruct the patient to continue dry decontamination procedures until you are able to initiate wet decontamination

- provide access to warm soapy water

- instruct patient to initiate ‘rinse, wipe, rinse’ decontamination

14.2 Annex 2: Integrated care board (ICB) system coordination

In line with the NHS emergency preparedness, resilience and response (EPRR) framework, ICB’s are category 1 responders and are responsible for coordinating multi-agency planning and the NHS system-wide response to incidents and emergencies.

In the event of a CBRN incident it is likely that the level of response may escalate quickly. As such, in addition to supporting providers of health services they commission to ensure they have appropriate and proportionate arrangements in place to provide an effective initial response, an ICB must also be prepared to coordinate a system wide (level 2) response, as well as collaborate with partners in support of a regionally or nationally coordinated response (level 3 or 4). See NHS EPRR framework for further details of NHS incident response levels.

ICBs are required to have appropriately trained staff to respond to incidents and emergencies in and out of hours. To support ICB command and control arrangements during incidents involving hazardous substances and CBRN materials, the IOR ‘recognise, assess and react’ principles can be adapted to assist responding ICB staff to coordinate a system-wide response.

This process will also facilitate upwards reporting and escalation of issues to NHS England and ensure all ICB’s follow the same procedure, which will in turn, support situational awareness at a regional and national level.

Recognise

Providers are expected to escalate issues into the ICB that may lead to, or have resulted in, an incident declaration. It is important for the ICB to recognise that if the declaration of the incident is related to contamination this may cause disruption at a system level. When an activation is received through the on-call system there are a set of ‘recognise’ questions that should be asked.

- How have you been alerted to the incident?

- Do you know the actual or potential contaminant involved?

- How many self-presenters have attended, adults and paediatrics?

- Are your decontamination facilities operational?

- What is the impact on critical service delivery?

- Has a divert been requested?

- If presented to a community, mental health or primary care facility, do they have emergency services presence on site and how are incident patients being assessed and non-incident patients redirected?

- Have decontaminated casualties been conveyed by the ambulance service? If so, how many and what is the breakdown of category (P1-P3)?

- If presenting through urgent and emergency care or 111, do pathways have agreed messaging?

- What system level support do you require?

- Have any media messages been released?

Assess

- What is the effect on the system, are our communities able to access care at place-based facilities? Consider cordons that may be in place (cordon distances will vary depending on the threat and joint risk assessment).

- What admission avoidance strategies can be deployed to move flow away from the acute provider space?

- Will this incident affect discharge out of inpatient beds? Consider non-emergency patient transport discharges unable to access patient homes within a cordon.

- What communications are going to be shared with the wider community and health system?

- If in the minor injuries unit, community, urgent and emergency care or primary care space, how will assets be protected to maintain access for patients?

- At a system level what are the effects of the incident in the next 2 hours, 6 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours or longer?

- What is the expected recovery time?

React

- Consider activation of ICB incident response arrangements, including establishment of incident management teams and incident coordination centres to facilitate system coordination.

- Notify the NHS England regional team(s) of the situation as necessary.

- Be prepared to attend regional incident management team in a widespread incident.

- Convene a system level strategic call, ensure NHS England and system EPRR teams are notified.

- Be prepared to attend local resilience forum tactical or strategic coordination group calls in a wider level incident, ensure any asks to, or from, multi-agency partners have been agreed at a system level.

- Information sharing with partner organisations is a crucial element of civil protection work and underpins all forms of cooperation, however consideration should be given to information governance principles when sharing confidential and sensitive information, particularly during incidents that are suspected to involve criminal or terrorism related activity.

- Are there any displaced residents that have been moved to local authority led evacuation centres where primary care support may be needed? If so, work with ICB primary care teams and safeguarding to support the strategic response.

- Gain assurance on the likely duration of the incident if it is a HazMat incident, in a CBRN incident this will be led at a national level and national command and control will be followed.

- Coordinate a system approach to recovery for affected organisations at the earliest opportunity.

14.3 Annex 3: Glossary

BAD COLDS

Substance assessment tool (Behaviour, Appearance, Dissemination, Colour, Odour, Likeness, Deliberate, Symptoms).

Casualty

Person who is symptomatic and contaminated presenting to emergency services and at health facilities.

Caustic

Capable of burning, corroding, dissolving, or eating away by chemical action. Causing a burning or stinging sensation. Causing irritation.

CBRN and CBRN(e)

Chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear substances or materials and term used to describe CBRN substances or materials combined with explosives.

CBRN(e) terrorism is the actual or threatened dispersal of CBRN material (either on their own or in combination with each other or with explosives), with deliberate criminal, malicious or murderous intent.

COMAH sites

Sites covered by the Control of Major Accident Hazards (COMAH) Regulations 2015. The regulations cover any establishment storing or otherwise handling large quantities of hazardous industrial chemicals. They are designed to ensure establishments take measures to prevent major accidents and limit the consequences of any major accidents which do occur.

Contaminant

A substance in an incident or disruption that is either present in an environment where it does not belong or is present at levels that might cause harmful effects to humans or the environment.

Contamination

The presence of a minor and unwanted constituent (contaminant) in material, physical body, natural environment, at a workplace.

Clinical decontamination

The process where contaminated persons are treated individually by trained healthcare professionals using purpose designed decontamination equipment. The process of cleansing the human body and other surfaces to remove contaminants, or the possibility (or fear) of contamination, by hazardous materials including chemicals, radioactive substances, and infectious material.

CRESS

Casualty assessment tool (Consciousness, Respiration, Eyes, Skin, Secretions).

DIM

Detection, identification and monitoring.

Provided by fire and rescue services, DIM provides a capability to a major national incident, involving actual or potential chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) or hazardous materials (HazMat).

Dry decontamination

The blotting and rubbing of exposed skin surfaces with dry absorbent material.

DEFRA

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

ECOSA

Emergency Coordination of Scientific Advice.

Emergency decontamination

A procedure carried out in advance of specialist resources where it is judged as an imperative that decontamination of people is carried out as soon as possible.

Exposed persons

People who present at NHS funded provider locations or those at scene who are asymptomatic and may have been contaminated.

Exposure

Where someone has come into contact with a contaminant/hazardous material.

HART

Hazardous Area Response team.

Specially recruited and trained personnel who provide the ambulance response to major incidents involving hazardous materials, or which present hazardous environments, that have occurred as a result of an accident or have been caused deliberately.

HazMat

Abbreviation for hazardous materials although it is commonly used in relation to procedures, equipment and incidents involving hazardous materials.

IOR

Initial operational response.

The IOR Programme has been introduced by the Home Office across all blue light emergency services and to key first responders including the NHS, to improve patient outcomes following contamination with hazardous materials (HazMat) or a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) incident.

Improvised decontamination

The use of an immediately available method of decontamination prior to the use of specialist resources.

Interim decontamination

The use of standard equipment to provide a planned and structured decontamination process prior to the availability of purpose designed decontamination equipment.

JESIP

Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Programme.

A programme that aims to improve the ways in which police, fire and ambulance services work together at major and complex incidents.

M/ETHANE

The M/ETHANE model is an established reporting framework which provides a common structure for responders and their control rooms to share incident information.

It is recommended that this format is used for all incidents and be updated as the incident develops. For incidents falling below the major incident threshold M/ETHANE becomes an ‘ETHANE’ message.

NRECU

NHS Resilience Emergency Capabilities Unit (ECU).

NHS Resilience ECU works with NHS ambulance services and providers of NHS funded services in England to ensure NHS clinicians will be able to deploy safely and effectively to provide care to patients within high-risk complex and major incidents.

This risk is mitigated through the maintenance of a national safe system of work which includes consistent training standards, competence and national operating procedures.

NHS

National Health Service.

ORCHIDS

Optimisation through Research of Chemical Incident Decontamination Systems.

The ORCHIDS project aims to strengthen the preparedness of European countries to react to incidents involving the deliberate release of potentially hazardous substances. Response capabilities can be enhanced by identifying ways of optimising decontamination processes for emergencies involving large numbers of casualties.

Patient

A person who may require disrobing and decontamination having been at or near the location of a hazardous materials release and who was potentially exposed and therefore potentially contaminated and who may require some form of care (for example, decontamination, supportive medical care, lifesaving interventions, antidote therapy, communication, and reassurance).

PPE

Personal protective equipment.

Protective clothing, helmets, goggles or other garment designed to protect the wearer’s body from injury.

Self-presenters

People may leave a scene before cordons are put in place, either attempting to flee from danger or not immediately realising that they may have been contaminated and turn up at an emergency department, a primary or community care facility, or another healthcare facility.

SORT

Specialist Operational Response team.

SORT operatives are drawn from ambulance service’s frontline paramedics and emergency responders. They are experienced ambulance staff who deal with medical emergencies on a day-to-day basis. They have received additional specialist training to support complex emergencies including marauding terrorist attack and incidents involving CBRN.

Wet decontamination

The use of water to aid the removal or reduction of hazardous materials to lower the risk of further harm to those affected and/or cross contamination.

Worried well

Members of the public who may be near to an incident when it happens, or who have heard about it third hand, and who are worried that they have been affected by the incident or consider themselves likely to need medical intervention.

UKHSA

United Kingdom Health Security Agency.

UKHSA is charged with protecting the health and wellbeing of United Kingdom citizens from infectious diseases and with preventing harm and reducing impacts when hazards involving chemicals, poisons or radiation occur.

14.4 Annex 4: Example risk assessment template

Download the example risk assessment template.

14.5 Annex 5: Useful resources

- Triage, monitoring, and treatment of mass casualty events involving chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear agents – PubMed Central (nih.gov)

- Mass casualty decontamination guidance and psychosocial aspects of CBRN incident management: a review and synthesis – PubMed Central (nih.gov)

- Mass casualty decontamination for chemical incidents: research outcomes and future priorities – PubMed Central (nih.gov)

- Mass casualty decontamination for chemical incidents: research outcomes and future priorities – PubMed Central (nih.gov)

- Responding to CBRN events: Joint Operating Principles for the Emergency Services – JESIP [official: sensitive] (Resilience Direct – restricted access – registration required)

- Triage, monitoring and treatment of people exposed to the malevolent use of ionising radiation (who.int)

- Rapid screening for internal radioactive contamination: training resource – PHE 2012

- The Optimisation through Research of Chemical Incident Decontamination Systems (ORCHIDS) projects

- Primary response incident scene management (PRISM): guidance for the operational response to chemical incidents

- RMU: Planning and Operational Guidance (HPA-CRCE-017) (2011) Health Protection Agency

- Accessible Information Standard – NHS England

Publication reference: PRN00895_i