Summary

The OPD pathway

The OPD pathway is a set of psychologically-informed services operating across criminal justice and health, underpinned by a set of principles and quality standards. Using evidence-based relational and environmental approaches, it aims to reduce risk associated with serious reoffending and improve mental health within a high-risk, high-harm cohort likely to meet the clinical threshold for a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’.

The OPD pathway is a jointly funded partnership between His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) and NHS England. It is a long-term change programme that commissions treatment and support services nationally for people with ‘personality disorder’, whose complex mental health problems are linked to their serious offending. The OPD pathway has been set up as a ‘demonstrator’ initiative; it aims to pilot and evaluate new approaches to interventions for this highly complex group.

Services for people in scope are provided in prisons, adult secure mental health services and the community. The OPD pathway provides the framework that underpins the commissioning of these services and enables health and criminal justice agencies to provide a single service offer. It also provides specialist training and support for staff.

The OPD pathway is not a single entity, but a series of connected interventions and activities. All services follow the same principles and work toward the overarching OPD pathway aims but provide different functions to support people through their sentence and according to their intervention and management needs.

For the next 5-year period, the OPD pathway will remain a joint change programme between NHS England and HMPPS. This will give time to continue to build the evidence base and embed current organisational reforms sufficiently for discussions about mainstreaming to begin.

A joint vision

Both host agencies, the NHS and HMPPS, share these overarching aims:

- A reduction in repeat, high-harm offending.

- Improved psychological health, wellbeing, pro-social behaviour and relational outcomes.

- Improved competence, confidence and wellbeing of staff working with people in the criminal justice system showing personality difficulties.

- Increased efficiency, cost-effectiveness and quality of OPD pathway services.

Neither agency can address these aims alone: success can only be achieved through a joint, integrated approach at all levels. This strategy restates the shared commitment to these four overarching aims and to a joint approach to achieving them. Shared responsibility for the most complex people in the criminal justice system remains the core principle that underpins the pathway.

The joint aspiration is to have a more therapeutically-minded and compassionate prison and probation service that will deliver the pathway’s aims by making therapeutic use of the relationships between people. This will involve psychologically-informed practice embedded across HMPPS, and a prison system that understands and creates enabling environments that deliver opportunities for people to tackle their offending and improve their mental health. These ‘relational environments’ are at the heart of the pathway and deliver evidence-based, psychologically-informed practice, where staff are empowered by a reflective practice culture.

Achievements over the first ten years

- The OPD pathway has demonstrated that a joint programme between agencies and departments can be delivered.

- The concept has been established that there is a functional link between complex mental health and offending and that the two agencies can effectively work together to address it.

- A growing network of connected, innovative services has been established, underpinned by evidence-based quality standards and principles that meet people’s needs, while recognising that one size does not fit all.

- Psychologically informed consultancy has been embedded across probation, and is available to all probation practitioners.

- The number of treatment places in prisons has increased, with an intervention and risk management service rolled out across probation.

- A new model for a psychologically informed planned environment has been piloted and developed, which supports people to access the next stage of their pathway both in prisons and in the community.

- Evaluation has been embedded into the pathway across existing and new initiatives and through a robust quality standards framework.

Aims for the next 5 years

The next steps are to consolidate and build on the work so far. Following a system-wide strategic review of the pathway, the following eight ambitions have been identified to support this. They sit within two types of considerations: pathway and system, in accordance with the pathway’s dual emphasis on both service development and system influence and improvement. Each ambition has a set of related objectives for 2023 to 2028:

Pathway-level ambitions

- Responding to unmet complexity of need.

- Pathway consistency and quality.

- Promoting diversity and inclusion.

- Enhancing identification, pathway planning, referrals and access.

- Strengthening transitional support.

System-level ambitions

- Supporting a whole system response to complexity, risk and need.

- Prioritising a relational practice culture.

- Building the evidence base.

Over the next 5 years, working toward these ambitions will:

- Build the evidence base, by designing high-quality evaluations that are guided by the OPD pathway’s theory of change, and cascade learning more widely about using psychologically-informed, relational approaches to working with complexity.

- Create consistency in delivery, by filling gaps in service provision and in pathway planning, to realise the vision of a complete pathway from community to community.

- Achieve consistency in quality, by developing data capacity, producing centralised guidance to support delivery and streamlining the workforce development offer.

The strategic landscape

The original concept of an OPD pathway was developed in response to recommendations made in the Bradley Review (2009) and built on the Department of Health and Social Care’s acknowledgment of poor service delivery for those diagnosed with ‘personality disorder’. The OPD pathway was designed as the successor to the dangerous and severe personality disorder strategy (1999) and sought to respond to the learning from this national programme. [1]

The original OPD pathway strategy was launched in 2011 following a public consultation. The 2011 strategy set out the pathway’s high and intermediate-level aims and identified the core elements that services would need to achieve to meet these aims. These continue to be:

- Operating from community to community – this assumes that those who meet the screening criteria originate from the community and will return there once any secure care is completed.

- Providing psychologically informed case management and progression as well as intervention.

- Investing continuously in the workforce.

The original strategy also established the pathway’s co-commissioning model of joint working between criminal justice and health services and set out intentions to provide a range of new service models in community, custody and medium secure units, delivered in partnership between health, prisons and probation. This recognised the need for health and justice agencies to work together to provide for this population. See Annex B for a detailed description of OPD pathway service types and definitions.

The strategy was updated and re-published in 2015, building on the foundations established in the first 4 years of delivery. It introduced:

- Expectations about the involvement of staff and service participants [2] in service delivery and development. See Annex A.

- A clear set of principles underpinning the OPD pathway. See Annex D.

Building on the 2015 strategy, the following models were established to define what good looks like for the OPD pathway:

- The development of an OPD pathway theory of change. See Annex C.

- A set of quality standards based on the evidence, and the monitoring of those standards by co-commissioners to improve service delivery. See Annex D.

This document introduces the 2023 to 2028 strategic direction for the OPD pathway. It does so within the context of large-scale policy and structural reforms across both host organisations, NHS England and HMPPS. It is vital that the OPD pathway takes opportunities to inform implementation and development of new policy and strategies where appropriate, alongside understanding any impact of these on the pathway itself.

Significant current opportunities for reform relevant to the OPD pathway include, but are not limited to, the following government and agency strategies and policy expectations:

- Prisons Strategy White Paper (2022)

- Health and justice framework for integration 2022-2025: improving lives, reducing inequality (2022)

- Draft Mental Health Bill (2022)

- HMPPS The target operating model for probation services in England and Wales. Probation Reform Programme (2021)

- The internal strategy of Transforming Delivery in Prisons

- Core20plus5 approach (2021), an NHS England strategy aiming to tackle health inequality

- HMPPS Business strategy: shaping our future (2020)

- NHS Long Term Plan (2019)

- Joint HMPPS and NHS England Women’s custodial estate review (2013) and the review of health and social care in the women’s prison estate.

Each of these strategies emphasises the need to work in partnership, to address the health inequalities present in a criminal justice population, and to provide the evidence-based conditions that are necessary to tackle health and wellbeing alongside reducing reoffending. The OPD pathway is well-placed to deliver contributions across this spectrum of reform.

Within the NHS, a shift away from national to place-based commissioning where appropriate, and the development of the relevant structures to support this, mean that new collaborative networks will need to be developed, and a new shared, evidence-based vision formulated.

Across government, there is considerable emphasis on tackling the mental health of the criminal justice population following the Justice Select Committee report into mental health in prisons (2022) and the Joint thematic inspection (2021) into the criminal justice journey for individuals with mental health needs and disorders. The OPD pathway is explicitly mentioned in a positive light in the latter report with a recommendation that the pathway should be made available to all people engaged with probation. Significant policy and legal reforms are also underway to modernise the Mental Health Act and the OPD pathway will need to respond to the implications of these.

Since the 2015 strategy there has been much debate between those living with ‘diagnosable’ mental health conditions and professionals, with regard to the label ‘personality disorder’, the status and utility of a diagnosis, and what other frameworks might replace a traditional medical model – for example, the Power threat meaning framework (2018). This strategy is not the place to debate these complex and important issues, but we acknowledge that the OPD pathway should and will contribute to those discussions as appropriate.

This strategy also launches at the time of recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. This is estimated to have had a significant impact on mental health both generally and within criminal justice settings [3] and has taken a toll on staff who were redeployed to managing the pandemic. The 2023 to 2028 OPD pathway strategy acknowledges the impact on OPD pathway services and, where possible, is taking steps to address this, in line with two of the three high-level objectives in the 2022 to 2023 NHS Mandate (2022): the continued COVID-19 response and recovery of the health system.

Evidence suggests that recovery from a crisis or disaster needs to be led by the community involved [4], with central leads providing a ‘scaffold’ of expertise which communities can then adapt to their needs to generate their own leadership and capability. As the OPD pathway principles accord with this evidence regarding engagement and community building, OPD pathway services should be ideally placed to recover and thrive in a ‘living with COVID-19’ world.

Finally, in setting out this strategy, we recognise that external factors may impact on its deliverability. Resources both in terms of the financial landscape and the ongoing difficulties around the recruitment and retention of staff may have implications for OPD pathway services. Over the next few years, we anticipate a continued pressure on public funding, and with this strategy we renew our commitment to the best use of the resources we have, including by taking opportunities to prepare for future spending reviews. By setting out a clear strategic direction the expectation is that the pathway will be better able to respond creatively to these challenges.

Target population

The OPD pathway’s target population is:

Men

- At any point during their current sentence, assessed as high or very high risk of serious harm to others, and serving a sentence for a violent or sexual index offence.

- Likely to satisfy the criteria for ‘personality disorder’, to a level that has significant and severe consequences for themselves and others; and

- A clinically justifiable link between the ‘personality disorder’ and the risk.

Women

- On their current sentence, are multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA) eligible or have a high or very high risk of serious harm score; and

- Likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for ‘personality disorder’, to a level that has significant and severe consequences for themselves and others, as measured by scoring 10 or more on the HMPPS Offender Assessment System (OASys) women’s OPD pathway screen.

This population is a highly challenging cohort within the criminal justice system who exhibit severe, complex interpersonal problems and personality difficulties that could be diagnosed as ‘personality disorder’. These difficulties are usually associated with deprived, abusive, neglectful or difficult childhoods. [5].

This cohort often have a turbulent history of engagement with services, as well as presenting ongoing concerns regarding their risk and outstanding support needs. They may present with disruptive and risky behaviours that services find challenging to manage and which can interfere with the smooth running of the organisation. It is their need for carefully planned management, in addition to any interventions, that sets them apart from others; their personality difficulties may be linked to their offending or be stopping them from engaging in risk/offending reduction work.

The OPD pathway works with people who have a confirmed diagnosis of personality disorder and/or may already be receiving clinical care with regard to their personality difficulties, as well as those who do not have a formal diagnosis. Therefore, clinical assessments are not required for all those on the pathway.

The criteria for the target population to enter the OPD pathway are applicable to sentenced adults (18 years and over). The OPD pathway approach to people who are transgender, gender-fluid, gender-neutral, intersex or non-binary is described in Annex A.

Approximately 35,000 people (32,000 men and 3,000 women) satisfy these criteria across community and custody at any one time, excluding those who are currently detained under the Mental Health Act and residing in a secure hospital. Of this total, just over 50% will receive additional OPD pathway activity in the form of psychologically informed work, and approximately 3,000 individuals access at least one OPD pathway intervention at any one time.

Aims and outcomes of the OPD pathway

The aims of the OPD pathway reflect its partnership approach; to improve public protection and reduce reoffending while increasing the psychological health of those in scope by developing a comprehensive and effective pathway of services for this complex and difficult to manage group.

The four overarching aims of the OPD pathway are:

- A reduction in repeat, high-harm offending.

- Improved psychological health, wellbeing, pro-social behaviour and relational outcomes.

- Improved competence, confidence and wellbeing of staff working with people in the criminal justice system showing personality difficulties.

- Increased efficiency, cost- effectiveness and quality of OPD pathway services.

For further details about the OPD pathway’s high-level aims, intermediate indicators and evidence base, see Annex A: supplementary information about the OPD pathway.

OPD pathway theory of change

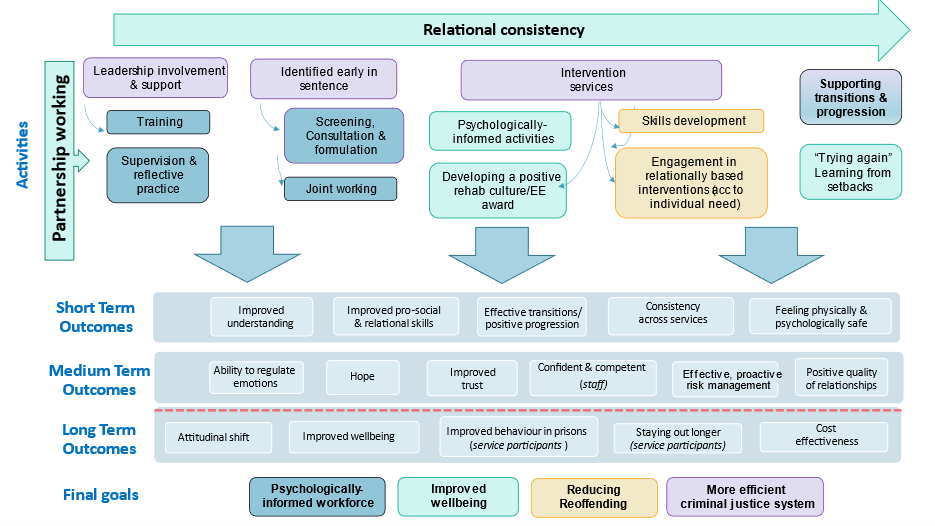

The OPD pathway theory of change outlines the key activities and the expected outcomes that will lead to the pathway meeting its four high-level aims. By identifying specific activities relevant to service participants, staff and wider systems, the aim is to understand the mechanisms of change and anticipated significant outcomes in the short, medium and long term. This allows a chain of events to be identified, showing what is expected to be effective and when by. Figure 5 below shows the overarching theory of change for the OPD pathway. As shown in Annex C, this is further split into three nests (staff, service participant and systemic), to reflect the pathway’s key stakeholders and objectives .

Figure 5: Theory of change for the OPD pathway

Commissioning and providing the pathway

Commissioning model

The total resource envelope for the OPD pathway is currently circa £72 million, comprised of £58 million from NHS England and £14 million from HMPPS. This figure does not include funding for aligned services that deliver important parts of the pathway such as the mainstream democratic therapeutic communities and high secure hospital beds. The resource sits under the responsibility of NHS England Specialised Commissioning and HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) Rehabilitation and Care Services Group and is additional to the core health and HMPPS service offer.

The OPD pathway is commissioned on a regional basis in line with NHS England regional boundaries as well as Wales (see below), with national oversight to ensure consistency and quality. Each regional footprint has one HMPPS and one NHS commissioner, who jointly commission OPD pathway services. This joint commissioning cycle (needs assessment, specification of service, procurement, contracting, performance management and quality assurance) strengthens the ability of HMPPS and the NHS to provide joint operations and take joint responsibility for the cohort who satisfy the screening criteria. It also allows shared problem-solving and navigation of two complex organisations.

All services are commissioned against either NHS England or HMPPS specifications and guidance. All have the same quality and information requirements irrespective of the transactional detail (NHS England contract or HMPPS service level agreement).

A national partnership agreement is in place between NHS England and HMPPS in respect of the OPD pathway. This sets out the shared objectives and commitments for both organisations and how they work together to deliver the pathway outcomes. This agreement sits alongside the HM Government partnership agreement for health and social care for England and illustrates the importance of the wider partnerships OPD pathway delivery teams need to engage with to successfully integrate with all HMPPS and NHS England commissioned provision in the criminal justice system.

Wales

HMPPS manages prisons and probation services across England and Wales; however, NHS England does not commission services in Wales. To ensure consistency of approach, the OPD pathway engages directly with a partnership of Welsh health boards and the Welsh government to ensure an equivalence of provision within the pathway. The funding for the Welsh pathway exists as a share of the original dangerous and severe personality disorder budget and funds from the decommissioning of high secure beds (part of the original OPD pathway strategy). Further developments in Wales will depend on discussions and negotiations with the Welsh government given that NHS England has no commissioning authority there, alongside capitalising and negotiating funding opportunities from within HMPPS.

Adult secure mental health services

The OPD pathway commissions two medium secure units (MSUs) to deliver specific OPD pathway interventions. The OPD pathway intervention service specification and associated guidance document supplement the national service specification for adult secure services, to support this activity. Adult secure mental health services have predominantly moved into NHS-led provider collaborative arrangements and will also be required to establish close relationships with their relevant integrated care boards across England. Four more specialised adult services are being retained by NHS England: high secure services, women’s enhanced medium secure services, secure acquired brain injury services and secure deaf services.

OPD pathway co-commissioners will work with the two MSU services to ensure that they are able to continue to support the wider OPD pathway while remaining aligned to the NHS-led provider collaborative arrangements.

High secure hospitals will continue to be commissioned through NHS England Specialised Commissioning arrangements, with close working arrangements with the NHS-led provider collaboratives. The high secure hospitals will continue to provide beds for patients diagnosed with personality disorder and therefore they form a critical component of the overall OPD pathway.

About the OPD pathway strategic ambitions 2023 to 2028

The OPD pathway was established as an efficiency change programme to recycle existing resources and provide an innovative, jointly delivered set of services for those with the most complex needs within the criminal justice and health systems. This vision is broadly being achieved; however, the experience of OPD pathway services to date, reflected through the ongoing commissioning cycle and wider feedback gathered during the strategic review, identifies that some highly complex individuals, particularly among those in custodial settings, have difficulties that are not yet being adequately addressed. This impacts on the public purse, poses an ongoing risk to public protection, and has implications for the health and wellbeing of those living and working in custodial and community settings. Gaps remain in service provision and there is more work to do to enable the vision of a holistic pathway.

The OPD pathway adds significant expertise to the treatment and management of high-risk individuals with pervasive psychological difficulties in the criminal justice and health systems. Other pathways of care have a similarly strong track record of relational and evidence-based practice in this field. Collaborative partnerships, along with effective signposting and a commitment to developing co-ordinated approaches to care, will therefore continue to be essential to the success of the OPD pathway as it looks to consolidate its work over the next phase of delivery.

How the 2023 to 2028 strategy was developed

A system-wide review was undertaken to inform the development of the 2023 to 2028 strategy. The phases of the review and the stakeholder consultation activities completed are outlined below.

- Early engagement – initial views about the OPD pathway were sought from people working in or using OPD services and from other key stakeholders, through online and paper surveys, meetings and one-to-one interviews.

- Thematic engagement – themes emerging from early engagement were used to structure focus groups with OPD pathway staff and participants to gather more detailed feedback on key issues for the pathway.

- Identification of key themes – feedback obtained from early and thematic engagement was reviewed, and around 30 themes were identified as central to the pathway’s priorities.

Stakeholder consultation activities completed

- 115 service participants contributed their views via focus groups held across OPD services in custody, community and health.

- 113 postal surveys received from those using OPD pathway services.

- 100 OPD services in custody, community and health settings represented through online survey returns.

- 55 OPD service leads gave detailed feedback in focus groups or individual meetings

- 26 individual or team meetings held with senior HMPPS and NHS stakeholders.

- 22 focus groups with service participants held across OPD services in custody, community and health.

- 2 strategy events held to gather staff views through thematic focus groups.

The eight key ambitions can broadly be described as two related sets of objectives, split across pathway and system considerations:

Pathway-level ambitions

- Responding to unmet complexity of need (A1).

- Pathway consistency and quality (A2).

- Promoting diversity and inclusion (A3).

- Enhancing identification, pathway planning, referrals and access (A4).

- Strengthening transitional support (A5).

System-level ambitions

- Supporting a whole system response to complexity, risk and need (A6).

- Prioritising a relational practice culture (A7)

- Building the evidence base (A8)

Each of these ambitions is described in more detail in the next section. For each ambition, examples are given of success so far. Areas for development, objectives and feedback from a range of stakeholders are also given. A delivery timeline for the objectives is provided at Annex E.

OPD pathway strategic ambitions 2023 to 2028

Responding to unmet complexity of need (A1)

Pathway ambition (A1)

Expand support for those in scope who the OPD pathway has not yet reached, helping more people become stable enough to progress, while seeking to extend OPD pathway approaches to working with complexity across the wider system.

Success so far (A1)

The OPD pathway enhanced support service (ESS), currently operating in four prisons, supports a small cohort of the most highly complex and challenging prisoners, and aims to reduce the negative impact of their violent, disruptive and self-injurious behaviour. This cohort (some of whom potentially do not meet the criteria for the OPD pathway) have not responded to existing interventions. The service model uses a multidisciplinary staff team working in partnership across prison, healthcare and forensic psychology services. Such a model of delivery supports HMPPS strategic objectives to improve safety and reduce violence in prisons.

Areas for development (A1)

Consultation feedback from OPD pathway services suggests that a proportion of those who satisfy criteria for the OPD pathway – that is, have particularly high levels of complexity and need – are not yet ready to access interventions or OPD pathway services, and that there is a gap in provision for this group. Pilots indicate that OPD pathway ESS [6] and OPD pathway outreach services in prisons [7] may be effective in working with some of these high-risk, hard-to-reach prisoners. This includes people serving indeterminate sentences who are struggling to progress. These services aim to help people stabilise sufficiently so that they can engage in other pathway interventions. They have also provided crucial support within custodial settings, without which a hospital transfer may have been necessary. Following a positive evaluation of ESS at two of the original pilot sites, the OPD pathway will explore opportunities to expand ESS provision over the next 5 years within its existing services.

Feedback from the strategic review highlighted that it would be beneficial for the OPD pathway to expand its remit to work more widely with those who present with significant levels of complexity and need. This was seen as particularly relevant for prisoners in local and reception prisons, category C prisoners and those in segregation units. Not all these individuals would satisfy the OPD pathway screening criteria, and fulfilling these requests is beyond scope within the current funding envelope.

The overall focus of the OPD pathway remains those who satisfy the entry criteria. However, additional pilots for very high risk and/or challenging criminal justice cohorts who do not satisfy the screen threshold will be considered over the next 5 years of the pathway’s development, should resources become available.

Objectives (A1)

- Develop the service model in existing OPD intervention service sites to deliver an outreach service (eg ESS), where current funds allow. To have in place a plan for delivery at each site by 2025 with a view to full adoption across services by 2027.

- Develop a psychologically-informed action plan by 2024, in partnership with the HMPPS Public Protection Group, to set out how the OPD Pathway can better engage with the imprisonment for public protection (IPP) population.

- Develop psychologically-informed guidance for staff working with those the OPD pathway has not yet reached, particularly prisoners in local and reception prisons, category C prisoners and those in segregation units, ensuring this is co-produced with other key stakeholders, by 2027.

- Optimise the OPD core offender management (core OM) intervention for those highly complex individuals the OPD pathway has not yet reached, using the quality standards framework, by 2028.

- Draw up proposals for expansion of the ESS delivery model into prisons outside the existing OPD pathway footprint, for submission through the next spending review framework (expected by 2026) (subject to funding).

Stakeholder engagement responses (A1)

- “There are too many [OPD] services focusing on service users who access ‘progression’ type services and not nearly enough services for services users at the beginning stages of intervention, eg outreach services.” (OPD staff).

- “[People with] short sentences [are] written off as a group you can’t work with – but when you add all the short sentences up, they are long term. There are ways to engage with that group”. (OPD staff).

- “Some people arrive with really complex needs and they disrupt the whole unit. They should have access to more 1:1 work because they can take away the staff from the rest of us…”. (OPD participant).

- “We need to consider whether the pathway is able to provide all the interventions necessary for often very complex individuals with interconnected needs”. (OPD staff).

Pathway consistency and quality (A2)

Pathway ambition (A2)

Develop national pathway consistency and quality by consolidating existing service provision, addressing regional disparities and creating opportunities for progression.

National pathway (A2.1)

Success so far (A2.1)

OPD pathway treatment services are now offered across all categories of prison, ensuring that a pathway of connected services is available.

Areas for development (A2.1)

The OPD pathway aims to provide consistency of support to the population who meet its criteria, and to ensure suitable opportunities for individuals to progress along the pathway from community to custody, and back to the community. There are, however, key gaps and disparities in service provision in custody, community and health which mean this has not yet been achieved. There is a need for a single, overarching specification for OPD pathway services to ensure a coherent approach to the commissioning of services. Further work is required to clearly articulate population need and gaps in provision. This will be used to inform future funding decisions should further resources become available. Women who satisfy the criteria for the pathway should have equitable access to a full range of OPD pathway provision in custody and the community without having to be relocated significant distances from local personal and professional support networks.

Objectives (A2.1)

- Transition all OPD pathway commissioned services onto an outcomes-focused overarching service specification for the national OPD pathway, by 2027.

- To support the OPD pathway single specification, develop a suite of service and thematic guidance, collaboratively and with the involvement of service participants, and considering issues of intersectionality, by 2027.

- Develop a shared understanding of the full pathway and governance requirements for medication to manage sexual arousal (MMSA) services in custody and community by 2026, working in partnership with NHS England Health and Justice.

- With key stakeholders, explore opportunities over the course of this strategy for jointly commissioned initiatives to improve consistency of service provision across the stakeholder landscape.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A2.1)

- “[We] won’t know if the whole pathway is delivering what it is meant to without national consistency. It brings containment – it brings principles, red lines, containing scaffolding. ‘We are doing it our way’ is what it was like in the past [dangerous and severe personality disorder programme]. There was a lot of charismatic authority. I would not want to go back to that”. (OPD staff).

- “Money and time should be spent on making sure the pathway is much more coherent/joined up so that those of us using the pathway are encouraged to make informed decisions”. (OPD participant).

Custodial pathway (A2.2)

Success so far (A2.2)

Places in OPD treatment services and psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs) have expanded threefold for women in prison since 2011, with some level of OPD pathway provision now available in all but one women’s closed prisons, creating a network of women’s services across the country.

Areas for development (A2.2)

Pathway progression for some cohorts requires more onward provision tailored to their needs, particularly:

- In response to population flows and prisoner need, the OPD pathway needs to review the treatment and progression options it offers for prisoners in the category C estate, to better support a pathway from higher security conditions.

- The OPD pathway would benefit from additional service provision and support for those with learning disabilities who meet the criteria for the OPD pathway, to build on the enhanced therapeutic community (TC+) service currently commissioned for this population.

- The OPD pathway should identify opportunities to expand service provision for individuals within the target population convicted of sexual offences.

Objectives (A2.2)

- Commission a progression option suitable for those with learning disabilities by 2024.

- Create pathway progression opportunities for category C prisoners by increasing service provision, eg treatment opportunities, by 2025.

- Complete a category C commissioning plan based on stakeholder feedback and known gaps by 2024.

- Specify OPD pathway commissioning intentions for the women’s estate by 2024, informed by, for example, the Heath and justice women’s review, OPD pathway data and stakeholder feedback from the strategic review.

- Align all legacy dangerous and severe personality disorder services with the OPD pathway overarching specification, contracting and commissioning intentions by 2027.

- Assess the impact of future population flows, need and new prison builds, to inform future commissioning intentions. To be completed over the course of this strategy.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A2.2)

- “We need to improve services for category A vulnerable prisoners. This causes the biggest issue around progression and has a negative impact on those who feel they cannot progress”. (OPD staff).

- “There is a need for more treatment services, in particular for those who are not suitable for a TC but not ready for a PIPE.” (OPD staff).

Community pathway (A2.3)

Success so far (A2.3)

Intensive intervention risk management services (IIRMS) have been rolled out across the country, offering a dedicated service to those released from prison. Intervention and enhanced risk management are now provided for the highest risk and most difficult to manage individuals in the community; this includes maintaining contact with those recalled into custody.

Areas for development (A2.3)

Gaps in approved premises PIPE provision result in out of area placements, which make it more difficult for people living in approved premises to build relationships within their local communities; this can also impact on risk management. While increased resources need to be invested in residential support, there is also a wider system need to support non-OPD pathway services in working with complex individuals in the community.

IIRMS provision expanded rapidly following an increase in funding from 2019. Service provision has evolved in relation to the local landscape and resources and as a result of innovation in individual sites. Provision needs to be reviewed against the national IIRMS guidance to ensure that the central service offer is consistent with this guidance. This process will provide assurance that people subject to probation supervision receive a consistent service irrespective of where they live.

Objectives (A2.3)

- Every IIRMS to have a gender-specific offer for women, which is delivered in a women-only space, from 2025.

- Ensure equity of access to IIRMS for every probation delivery unit (PDU) caseload by 2026.

- Map provision to review effectiveness of the core OPD pathway offer within the approved premises estate, to inform core guidance for the overarching OPD pathway specification, by 2025. To deliver this alongside an evaluation of approved premises PIPEs

- Create women’s OPD (WOPD) enablers in IIRMS partnerships who will have an external-facing consultancy function. These posts will aim to support the capacity and expertise of mainstream community services for women, enabling them to work with those meeting the WOPD pathway criteria. Commissioners to explore whether this can be done within existing resources. To develop an action plan for delivery by 2025.

- Commission enhanced engagement and relational support services (EERSS) by 2025, subject to evaluation, for women in the South and the Midlands regions, to ensure regional parity.

- Ensure that core and IIRMS services work together to offer a seamless experience to people on probation by 2026, using the new OPD pathway single specification and guidance documentation.

- Develop a business case by 2026, either for spending review or underspend resources, to pilot an ESS in the community model, based on a multidisciplinary team, eg social workers and housing officers (subject to funding).

- Design and pilot different service models to deliver a positive housing outcome for those who meet screening criteria, by 2026, building on existing expertise and including an embedded evaluation. Develop a business case (subject to evaluation) for submission through the next spending review framework (subject to funding).

Stakeholder engagement responses (A2.3)

- “Access to community treatment is not equitable across different areas, with different models creating a postcode lottery”. (OPD staff).

- “A community-based TC would be really good to keep us supported on the outside so we have a group we can go to when things are hard”. (OPD participant).

- “Problems with accommodation are a recurring theme… and with limited options for support with this in the community (at least in our region), this can greatly affect what can be offered or engaged with through our service.” (OPD staff).

- “More support around housing needs and helping develop pathways in this area is likely to have a big impact on success”. (OPD staff).

- “Community provision is a massive hole… [we] do have IIRMS but the geography and landscape are not ideal – a 1-hour drive and 2 or 3 trains is not realistic for people. Community services do not even scratch the surface”. (OPD staff).

Adult secure mental health pathway (A2.4)

Areas for development (A2.4)

There are currently two medium secure units (MSUs) commissioned as part of the OPD pathway, which offer short-term assessment and treatment to people who meet both the criteria for the OPD pathway and for detention under the Mental Health Act. In nearly all cases, the individual’s onward pathway, following their period in hospital, will be through the prison estate. Wider (non-OPD) MSU provision is provided by NHS-led provider collaboratives as part of the wider adult secure pathway.

The OPD pathway needs to work closely with the emergent NHS structures and with wider adult secure mental health pathways, including on any plans for low, medium and high secure hospitals, to develop the quality of services provided, better understand the data, and ensure that existing provision both meets the level of need and enables patient flow.

Objectives (A2.4)

- Review OPD pathway MSUs by 2026 with input from the NHS England Specialised Commissioning Adult Secure Mental Health team and clinical reference group to ensure that the services (a) support OPD pathway outcomes, (b) are aligned with the developing structural reforms in the NHS and (c) provide a link back to standard NHS pathways of care.

- The overarching OPD pathway specification and guidance documents will (a) set out the OPD pathway MSU provision offer to determine the optimum service offer in those locations and (b) ensure the OPD pathway MSUs link to the care pathways set out in the other adult secure specifications, by 2027.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A2.4)

- “It’s like you’ve had people build up an armour to go through life, then you rip it off us before throwing us back into the war”. (OPD staff reporting feedback from a service participant who remitted to prison from hospital).

- There needs to be more medium security units and an adequate amount of low security units to automatically progress to. You cannot send patients back to prison after treatment; it makes no sense and serves no purpose if they have engaged and progressed”. (OPD participant).

- “We need to form better links with high secure hospitals and the category A team to form proper pathways”. (OPD participant).

- “What OPD provision is missing – clear pathway from high secure hospital to prison that is known to partners”. (senior OPD stakeholder).

Promoting diversity and inclusion (A3)

Developing an intersectional approach to diversity (A3.1)

Pathway ambition (A3.1)

Embed a systemic approach to equality and diversity across the OPD pathway that is psychologically informed, increases engagement of under-represented groups within OPD pathway participants and staff, and promotes inclusion and innovation in working with diverse communities.

Successes so far (A3.1)

- A separate women’s OPD (WOPD) pathway strategy was drafted in 2011, in recognition of the particular complexity and multiplicity of the needs of women in the criminal justice system, especially those who also have mental health difficulties. The 2011 strategy drove the commissioning of a range of gender-responsive services, which are now well-established in all regions.

- The deaf service prison in reach programme, commissioned by the OPD pathway since 2011, provides specialist psychological interventions for Deaf prisoners within the HMPPS estate, and consultation and training for those working with them. The team promotes understanding of the communication and cultural issues faced by Deaf people who are affected by mental health conditions.

Areas for development (A3.1)

To achieve pathway outcomes regarding inclusion, there is a need for psychologically-informed practice that understands a person’s experiences and how these influence their view of the world.

The OPD pathway is committed to being culturally informed and inclusive of all individuals who meet the criteria for the pathway, including those with protected characteristics. An OPD pathway diversity strategy has been in place since 2019 to help align the pathway with wider organisational priorities, including the Prisons strategy white paper equalities statement (2021), the Race equality in probation action plan (2021) and NHS England’s equality objectives (2016-20).

This OPD pathway strategy (2023 to 2028) is for both men and women, as well as those who are transgender, gender-fluid, gender-neutral, intersex or non-binary. It reaffirms the commitment to providing and improving gender-responsive pathways of care, with a particular emphasis on support at times of transition, strengthening WOPD’s integration with wider HMPPS and NHS England developments, and equalising the WOPD offer to women, regardless of postcode.

The initial focus of the OPD pathway diversity strategy has been improving the analysis of diversity data and staff training, and a race and ethnicity workstream. While this work will continue, the next phase will involve developing an intersectionality workstream that looks at the inequalities faced by people meeting the criteria for the OPD pathway from the perspective of multiple needs. This will acknowledge that highly complex people often have multiple protected characteristics that create layers of disadvantage, and so a whole-person approach is required to best understand how to adapt service delivery to meet their needs. The intersectionality workstream will also consider how ‘personality disorder’ impacts on the disadvantages faced by those with protected characteristics.

OPD pathway provision is directly informed by psychological case formulation. Over the next 5 years this needs to focus more explicitly on intersectionality so that the impact of all underpinning inequalities and cultural factors in a person’s life can be better understood. All staff working on the OPD pathway will also need the time and space to think in a psychologically-informed, whole-person way about how to deliver services that are responsive to diversity. This will be a critical component of the updated OPD workforce development strategy.

To ensure the needs are met of transgender people who satisfy the criteria for OPD pathway services, the OPD diversity strategy will include a transgender workstream and will prioritise working with the wider criminal justice and health systems to help develop a psychologically-informed, whole-system response to the needs of this group.

The OPD pathway will continue to work with the wider system to address known barriers to access for those with sensory impairment or physical disabilities, recognising that some individuals are unable to access an OPD pathway service as a result of external factors, such as lack of wheelchair access, which may be beyond the sole control of the OPD pathway.

Objectives (A3.1)

- Case formulation guidance is to be revised by the national OPD pathway case formulation working group, to include recommendations that support formulations to (a) be culturally competent and (b) consider protected characteristics from an intersectional perspective, beginning with race and ethnicity. To be piloted then fully rolled out by 2025.

- Review the OPD pathway diversity strategy by 2024 in line with the current understanding around equality and diversity, and include new workstreams to focus on intersectionality and transgender

- Ensure that all OPD pathway services have a diversity action plan by 2024, to start from the 2024/25 annual business plan.

- Review the applicability of the OPD pathway screening tools to the 18-25 male and female young adult cohort by 2026.

- The national OPD pathway team to provide structured opportunities over the course of this strategy for the OPD pathway workforce to meet and develop systems to embed diversity and inclusion.

- Seek opportunities over the course of this strategy to improve equitable access to OPD pathway services for those with physical disabilities and sensory impairment by linking in with HMPPS and NHS estate improvement programmes.

- OPD pathway co-commissioners to (a) work with existing services to plan how services can accept people with physical disabilities or sensory impairment and (b) when commissioning new services, to explicitly consider whether the site is able to make reasonable adjustments to accommodate those with physical disabilities or sensory impairment.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A3.1)

- “[We] need to ensure that identity is at the heart of formulation and recognise the impact this can have on thinking about sentence plans”. (OPD staff).

- “[There’s a] lack of overt attention to diversity needs. For example, many of the pro-social activities are subconsciously biased toward women and therefore unsuitable for transgender individuals, for example”. (OPD participant).

- “The lack of attention to diversity issues can lead to [people] feeling judged, unintentionally, and unable to bring issues to staff, particularly regarding religion and gender… we just don’t deal with it”. (OPD staff report on participant focus group).

- “I think there needs to be a far greater effort to ensure that individuals from BAME communities access OPD services in a meaningful way. Despite the over-representation of these groups in custody, they seem to be under-represented in OPD services, in my experience”. (OPD staff).

- “Plans need to be made to cope with older prisoners with disabilities as sometimes I struggle here”. (OPD participant).

- “I’m a Muslim so I know a lot of Black and Asian prisoners and they all asked why I was going on a ‘nut wing’ when I moved to the PIPE in prison. They didn’t get why I would. They’ve got a different idea about mental health”. (OPD participant).

Balancing inclusivity with stability (A3.2)

Pathway ambition (A3.2)

Support services to be inclusive, and able to accommodate individual need and a wide range of complex presentations, while maintaining the autonomy they need to safeguard the therapeutic environment.

Success so far (A3.2)

Bespoke provision for those with co-presenting learning disabilities and pervasive personality difficulties is commissioned through the therapeutic community+ (TC+) service in three prison establishments, ensuring that this under-served cohort has access to some level of tailored support appropriate to their needs.

Areas for development (A3.2)

The OPD pathway intermediate indicators (see Annex A) include reduction in the number and severity of incidents including general, violent and self-destructive behaviours. However, individuals with particularly challenging behaviour are often unable to meet service criteria because of these behaviours. As waiting times to access OPD pathway services in both custody and community can be lengthy, access to OPD pathway services for those who are suitable can be further restricted due to time left to serve or because their licence is of insufficient length.

In addition, significant numbers of people who satisfy the criteria for the OPD pathway have co-existing difficulties, in particular neurodiversity or a severe mental health or substance misuse problem. Since personality disorder has long been acknowledged as a diagnosis of exclusion, those with an additional diagnosis are at a particular disadvantage when seeking access to health services. The OPD pathway shares responsibility for their care and treatment with multiple specialist pathways and does not have the capacity to meet all presenting needs. The viability of providing tailored support for several very small groups at all OPD pathway sites when demand may be occasional or variable is also a key consideration and needs to be better understood. Work is needed to ensure that additional complexity does not result in exclusion from OPD pathway services.

Individuals convicted of sexual offences, who form a significant proportion of the OPD pathway population, also experience access challenges. They often have specific treatment needs and face difficulty in accessing OPD pathway services due to wider establishment rules related to their offence type.

While OPD pathway services aim to be inclusive, they would benefit from clearer national guidance as well as access to more specialist workforce training and supervisory support. This should help them accommodate more people with higher levels of need and co-presentations or with shorter time for treatment, while maintaining the safe and stable environment necessary for therapeutic work to take place. The OPD pathway also needs to develop joint collaborations with other care pathways to respond more effectively to the complex needs of the OPD pathway population.

Objectives (A3.2)

- Communicate national expectations for all OPD pathway services by 2024, as part of the national specification development, which support greater inclusivity of highly complex people while maintaining local autonomy according to service capacity.

- Deliver workstreams for substance misuse, neurodiversity and mental health/illness that will explore the interdependencies and relevant evidence base, and make recommendations for both the men’s and women’s pathways. To be completed by 2028 and to start with substance misuse.

- OPD pathway co-commissioners to (a) work with existing services to plan how the service can accept people with an index sexual offence and (b) when commissioning new services, to explicitly consider whether the site would accept people with an index sexual offence.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A3.2)

- “Some services do try to cater for all groups, but this does have an impact on training and skill set of staff teams. [We] also need to be aware of the resilience needed by staff teams”. (OPD staff).

- “Inclusivity is good in theory but hard in practice”. (OPD staff).

- “[I need] more stuff for my learning needs. I need telling more than once. More time so I can be heard”. (OPD participant).

Enhancing identification, pathway planning, referrals and access (A4)

Pathway ambition (A4)

Improve access to OPD pathway services across the country by raising awareness of services, so that staff, participants and external stakeholders can make well-informed decisions about sentence planning and pathway progression.

Successes so far (A4)

- Probation practitioners working in community and custodial settings across England and Wales now have access to psychological consultation to help them manage cases. This includes those cases where difficult and challenging behaviour could result in reoffending, breach of licence or lack of progression against sentence plan.

- OPD pathway case managers, case advisory groups and OPD pathway network meetings have been widely recognised as a positive development in OPD pathway planning. These have helped services move toward a collaborative, multidisciplinary way of finding a path forward for those highly complex and challenging individuals within OPD pathway services who are not progressing.

Areas for development (A4)

Work is required to tighten the link between sentence and pathway planning, particularly where placement in OPD pathway services is indicated. The process needs to be fully joined up, particularly for residential services within custody, where referrals often come through routes other than the probation practitioner. Pathway planning has been further complicated by the introduction of offender management in custody (OMiC) and the unification of the probation service, and a focus on this area is needed while these changes embed.

Most of the population sentenced to imprisonment for public protection (IPP) satisfy the criteria for the OPD pathway, so it is important to support the progression of this group and their equitable access to services, taking an innovative approach to meeting their needs.

The core offender management (core OM) OPD pathway specification needs to be amended to integrate OPD pathway planning with the sentence planning process in the HMPPS Offender Assessment System (OASys). Better integration of the pathway formulation with ongoing sentence management, including keywork, is also required. The core OM OPD pathway service is the foundation for the whole pathway and this work needs to align with other initiatives across HMPPS and NHS England.

Comprehensive and regular communications about OPD pathway services are needed across all agencies involved with sentence management, from court teams through to the directorate of security, category A boards and the parole board so that a system-wide understanding of the OPD pathway remit is developed. Services and service participants also need high quality information to support their decision-making.

Objectives (A4)

- Integrate the OPD pathway and a psychologically-informed approach with offender management processes by 2028, by working collaboratively with the relevant teams in probation.

- Support the wider system to work with the IPP population more effectively, eg by prioritising access to services where appropriate, and offering consultancy as indicated, by 2025.

- Develop a communications strategy for the OPD pathway by 2025 and start implementation by 2026.

- Provide fit for purpose case management processes by 2026 for complex women who satisfy the criteria for the OPD pathway but are not included in the Women’s Estate Case Advice and Support Panel caseload.

- Work with probation to develop a quality assurance process to oversee the core offender management service by 2026.

- OPD pathway services to develop a digital information pack by 2026, including the lived experience perspective, to support people to access the most appropriate service for their needs.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A4)

- “Things have greatly improved. I was around in dangerous and severe personality disorder days and back then it was individual services. Now we have the complex case boards [CAGs], about finding a pathway for stuck people. It is a huge improvement in pathway working – joint referral work with other services”. (OPD staff).

- If it’s in OASys it becomes part of the process – at the moment it’s an add on. We’ve slipped up, we should have had enhanced sentence planning rather than pathway planning at the side of sentence planning – the language matters around this stuff”. (OPD staff).

- “[There needs to be a] clearer understanding of how the pathway works and evidence/testimonials from others who have benefited. Show the value of the therapy and how it can help you progress”. (OPD participant).

- “Referrals come from the same people…Loads of people are missing out as their offender manager doesn’t have any understanding of our services”. (OPD staff).

Strengthening transitional support (A5)

Pathway ambition (A5)

Develop service handovers to be consistently managed and well planned at times of transition, and improve information sharing between OPD services, and with service participants and external partners.

Success so far (A5)

The OPD pathway enhanced resettlement service (PERS) supports those in open prisons whose problematic personality traits mean they are likely to have difficulty managing the transition from closed to open conditions, or from open conditions to the community. The service is currently being piloted and evaluated in five open prisons in the male estate. PERS offers keywork; an informal drop in facility offering emotional support to individuals at times of difficulty; and outreach and reintegration support providing people with practical help in developing community links.

Areas for development (A5)

Times of transition are particularly difficult for those using OPD pathway services, due to their vulnerability and high level of need. If people do not have access to the right support during transition, they have an increased likelihood of mental health deterioration, substance misuse and self-harm. On release from custody, there is a greater risk they will reoffend or be recalled to prison.

Feedback from the strategic review indicated that people need more support when progressing into or out of OPD pathway services. This is particularly the case in custodial settings for people:

- returning to a standard wing after leaving an OPD pathway service

- remitting from hospital

- moving from the youth to the adult estate.

In the community, as well as better support on release, people also need more help when:

- transitioning out of the OPD pathway once their licence ends

- moving from an OPD pathway to a non-OPD pathway service.

Managing transitions is a core task of psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs) and forms part of the ‘belonging’ enabling environments standard. Bespoke outreach roles have also been developed locally in some OPD pathway services to provide additional crossover support from custody into the community or from an approved premises. The OPD pathway will build on this existing good practice to make effective transitional support a cornerstone of service delivery.

Objectives (A5)

- Support the IIRMS network and relevant community and prison partners to improve the quality and frequency of IIRMS in-reach, informing associated guidance, by 2026.

- Establish a transitions task and finish group that develops guidance and expectations around management of pathway transitions by 2027, considering application of relevant quality standards and specifications.

- Identify the transitional support needs of the 18-25 male and female cohorts in the move from the youth to the adult estate by 2024, and recommend service developments informed by the evidence base, with the aim of improving stability, risk and wellbeing for this group.

- Confirm commissioning intentions for the provision of PERS in the male and female open estate by 2024, subject to evaluation. Develop PERS guidance in response to the evaluation and population flows by 2025.

- Evaluate provision of transitional support worker roles in WOPD pathway services and assess the feasibility of establishing this approach in the core women’s offer by 2025.

- Explore the use and impact of existing progression support roles in men’s OPD pathway services and assess the feasibility of extending this way of working across men’s services by 2027.

- Work with the HMPPS community accommodation service (CAS) to successfully implement and deliver the PIPE model in approved premises in existing identified sites in England and complete an evaluation of these services, by 2027.

- Develop an OPD pathway accommodation strategy by 2027 in conjunction with relevant stakeholders and taking account of existing services, evaluations and proposed pilots, to improve the housing options for OPD pathway participants.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A5)

- “I’d love to see more help and support for the younger generation when it is at a critical stage that could possibly save someone from a lifetime of struggles”. (OPD participant).

- “[Leaving prison is] another cliff edge, hugely anxiety provoking – people do not have the emotional vocab to describe the chaoticness of it all”. (OPD senior stakeholder).

- “I felt dropped like a sack of potatoes”. (OPD participant).

- “I think the pathway could improve the support we offer to individuals moving from one phase of their journey (eg from custody to the community) to another. Links between services could definitely be improved as each individual service is doing some brilliant work but I find this can often be lost when someone transitions from one service to another”. (OPD staff).

Supporting a whole system response to complexity, risk and need (A6)

System ambition (A6)

Develop the pathway to become more outward facing, providing consultancy and training beyond the OPD pathway and strengthening partnerships, to support a whole system response to the management of complexity, risk and need.

Success so far (A6)

Knowledge and understanding framework (KUF) training aims to develop the capabilities of multi-agency staff working with those diagnosed with ‘personality disorder’. In 2020, the OPD pathway and the NHS England Adult Mental Health team piloted a jointly commissioned national hub to develop and quality assure all KUF training which will run until 2024. This has provided valuable learning in developing a single training offer for staff across mental health and criminal justice services and will deliver a refreshed set of learning materials.

Areas for development (A6)

A whole-system, relational approach spanning multiple environments, agencies and pathways of care is needed if the outcomes for the OPD pathway are to be sustainably and effectively achieved. This includes sharing continuity of approach with additional prison environments and with mainstream services in custody and community. This will set up the ability to mainstream learning, and to shift the programme into ‘business as usual’. Key areas in HMPPS where the OPD pathway is currently working jointly with partners to embed a whole-system approach include:

- the Developing Wings initiative, a workstream of the Rehabilitative Culture Board (see A7)

- occupational therapy consultancy on regime reform in prisons

- offender management in custody (OMiC)

- the Prison Safety Programme.

The OPD pathway provides advice in relation to people who meet its screening criteria including strategically important groups such as those sentenced to imprisonment for public protection (IPP) and TACT (Terrorism Act) [8] offenders. In health, key areas of collaboration include Health and Justice initiatives such as RECONNECT and Enhanced RECONNECT [9], and Specialised Commissioning activity, including provider collaboratives and adult mental health services.

A consistent cross-sector approach will help reduce the risk of reoffending and of deterioration of stability once people leave the OPD pathway. Some of those who complete their period of licence and are no longer subject to probation supervision still have outstanding, and often significant, risks and support needs. Given the increasing number of people in the community participating in IIRMS, this cohort is likely to increase in significance over the next 5 years of the pathway’s development. Support for those post licence therefore needs to be considered even though they will be out of scope for OPD pathway interventions.

To support a whole-system response, the OPD pathway needs to engage in more outcomes-focused dialogue with those outside the pathway to share and discuss the developing evidence, learning and expertise. This dialogue should focus on relational practice and workforce development in working psychologically with those who are likely to meet the diagnostic criteria of ‘personality disorder’ and who have complex needs.

The strong OPD pathway joint working approach demonstrated in its clinical and operational partnerships needs to be consistently reflected in joint organisational governance arrangements, locally, regionally and nationally. This will improve oversight and consolidate effective partnership working in all areas of the pathway.

Objectives (A6)

- Create opportunities over the next 5 years to contribute to training and development for those working within OPD pathway host organisations, eg entry-level training, leadership training.

- All OPD pathway commissioned services to demonstrate strong and effective joint governance arrangements between their participating agencies by 2025, which mirror those in place at national level (that is, the joint NHS England and HMPPS OPD pathway programme board).

- Continue to expand the target audience for (awareness level) KUF and women’s KUF (W-KUF) over the course of this strategy to staff groups working with likely ‘personality disorder’ outside OPD pathway services.

- Use psychological consultancy, supervision and training to support those working in non-statutory agencies to work more effectively with people with likely personality disorder, by 2028.

- Seek opportunities to embed OPD pathway principles and practice over the course of this strategy by engaging with high-level strategic organisational change, eg integrated care systems, future regime design and probation unification.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A6)

- “[I need] continuity in every way. Continued support after my licence ends, especially around socialising. I spend 6 days of the week inside, I need connection to the outside world, but it is hostile”. (OPD participant).

- “The [HMPPS strategy] principles and people plan are very much aligned with OPD – your model is what we say about partnership working. The staff model of being professionally respectful, mutually supportive. What you’ve managed to achieve with collaborative working with two big systems is really important. You’ve managed the governance, the joint working. It’s a big achievement. So, the alignment is very clear (OPD senior stakeholder).

- “[In our region] the commissioners bring all elements of the community pathway together and review us jointly; it has really helped us. This type of governance is probably only possible in bigger urban settings but maybe could be replicated across the wider pathway/geography?” (OPD staff).

Prioritising a relational practice culture (A7)

System ambition (A7)

Embed psychologically-informed practice, training and support structures across the OPD pathway and within host organisations. These will help staff co-create healthy, pro-social environments and relationships with service participants and each other, enhancing the quality of clinical interventions and benefiting the wider culture.

Success so far (A7)

The Developing Wings Project aims to extend the OPD pathway approach by assisting prison wings to optimise the rehabilitative potential of their environment. By exporting the expertise used to create OPD pathway relational environments such as therapeutic communities and psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs), Developing Wings provides an evidence-based framework to help prisons develop their relational culture. Tailored support is offered through consultancy, training and an evaluation framework that measures individual and social climate changes over time.

Areas for development (A7)

Workforce development is one of the four high-level outcomes for the pathway and a separate OPD pathway workforce strategy is in place to support this. The demand on the OPD pathway workforce is twofold: to manage high-risk individuals presenting with severe personality difficulties and other multiple complex needs, and to do so by responding to them in a person-centred way. Relational practice gives priority to interpersonal relationships. It is the foundation on which effective interventions are based and it forms the conditions for a healthy relational environment. Importance must be given to:

- relationships based on reliability, consistency, curiosity, flexibility and authenticity

- an enabling and facilitating attitude

- an understanding of the conscious and unconscious lives of individuals and groups in their social field.

A culture of psychologically based quality-assured training and support must be maintained across the pathway for this to succeed. Key elements are:

- co-delivered personality disorder awareness training provided through the knowledge and understanding framework (KUF)

- regular clinical supervision, group reflective practice and internal networking opportunities for clinical, operational and national staff at all grades of post.

These factors contribute toward establishing and maintaining a positive social climate. When sufficient resource is given to supervision, staff feel better supported and are helped to consider and respond to the whole person and engage constructively with challenging behaviour. This can have a positive effect on the practitioner, service participant and service treatment effectiveness. [10] [11].

Co-production is an essential component in creating a pro-social culture [12] and a key part of the overarching involvement principle of the pathway. Lived experience roles bring a valuable dimension of support to services and the OPD pathway develops these in line with wider organisational initiatives such as NHS England’s Patient and public voice partners framework (2017), the Probation Service user involvement national delivery plan (2021) and the HMPPS Service user involvement standards of excellence (2021). The next steps for the pathway will be to build on its strong existing culture of involvement by creating lived experience networks and exploring the introduction of lived experience peer mentoring and employment opportunities within the OPD pathway workforce.

Objectives (A7)

- Refresh the OPD pathway involvement strategy by 2024, in response to the growing evidence base and practice and to incorporate learning from the strategic review feedback received from OPD pathway staff and service participants.

- Review and update the OPD pathway workforce development strategy by 2024, to support and respond to changing organisational cultures, emerging evidence, and learning from the pandemic.

- Enhance the quality of OPD pathway services by embedding the OPD pathway quality standards framework into service-level business plans by 2025. Support this further with the development and piloting of a co-produced peer-review process by 2026.

- Promote and develop the quality of formal and informal support and reflective spaces provided for OPD pathway staff, to meet the expectations of the quality standards framework, by 2026.

- Support and work with academic, clinical and lived experience colleagues, eg the British and Irish Group for the ‘Study of Personality Disorder (BIGSPD)’ community of practice, over the course of this strategy, to further develop the evidence base around relational practice.

- Explore the benefits of custodial services providing whole wing staff training in therapeutic approaches by 2027, with a view to further piloting.

- Support OPD pathway services to work toward the enabling environments standards by 2027, and work with the Royal College of Psychiatrists to develop the enabling environments network.

- Continue to fund academic work to ensure OPD pathway practice is based on developing knowledge in this field and that the pathway develops informed leadership that recognises relational principles and practice.

Stakeholder engagement responses (A7)

- “Found that [I’m] always treated like a person and not just a number”. (OPD participant).

- “Staff need support in order to support us”. (OPD participant).

- “I have to say that going into prisons, it is visiting a couple of PIPE units which has made me realise this is what prisons should be like. It is what has most impressed me. Phenomenal. PIPE is the answer to quite a few of the questions I think. It is very impressive stuff, especially the staff”. (OPD senior stakeholder).

- “[Having lived experience staff is] more tangible and convincing. It can be done and there’s more of a connection. It’s an understanding on a deeper level, it gives you hope that it could work for me as well”. (OPD participant).

Building the evidence base (A8)

System ambition (A8)

Improve the quality of, and make better use of, OPD pathway data, to inform pathway development and future evaluations, and carry out high-quality evaluations to help build the wider evidence base on ‘what works’.

Successes so far (A8)

- The OPD pathway quality standards framework was established in 2018. Evidence across health and criminal justice sectors was used to define the standards and determine the qualities that are measured. The quality framework is a tool that enables commissioners and services to ensure they are delivering the best they can with the funding available.

- Four externally commissioned evaluations were delivered following the 2015 OPD pathway strategy. These have been used, along with service-level evaluations, to inform a scoping review looking at the impact to date on the pathway, and to develop the OPD pathway theory of change.

Areas for development (A8)

As a demonstrator programme and in line with one of its key principles, the OPD pathway has a responsibility to evaluate whether it is achieving its intended outcomes. Most OPD pathway evaluations to date have focused on:

- learning about the implementation and quality of interventions that the pathway offers

- suggesting potential mechanisms of change and perceived impact.

Three external evaluations were delivered following the 2015 OPD pathway strategy and have been published on gov.uk. Two looked at preliminary evidence relating to psychologically informed planned environments (PIPEs), finding indicative evidence that prison progression PIPEs can improve social and relational functioning within prison. This was associated with higher social climate scores and positive staff disposition. A third evaluation looked at a specific shared reading intervention within PIPEs and found that those who participated experienced higher wellbeing scores.

A further large-scale, nationally commissioned project, the national evaluation of the OPD pathway (NEON), was also delivered and has been published on gov.uk. The national evaluation reported positive findings for prisoners, people on probation and staff but concluded that it was too soon to tell whether the OPD pathway is achieving its high-level outcomes. This was in part due to the complex nature of individuals on the pathway but there were also a number of significant data limitations.