Introduction

Acute respiratory infection (ARI), comprising of all viral and bacterial upper/lower respiratory tract infections, are one of the most common reasons for ED attendance (Hospital accident and emergency activity, 2022-23 – NHS Digital).

This document supports systems as they plan for the management of ARI in winter and beyond, as COVID-19 and other respiratory infections persist throughout the year.

The Fuller Stocktake report calls on systems to develop an integrated urgent care pathway. This document builds on this and aims to achieve a step towards a smoother urgent care interface between primary, community and secondary care.

It supports local systems to build on existing infrastructure to design ARI hub models to manage demand over winter, providing additional surge capacity to support primary and secondary care pressures and match the needs of their population. To support this local approach, this document contains links to the most up-to-date respiratory infection data to support operational planning.

This guidance replaces Combined adult and paediatric acute respiratory infection (ARI) hubs (previously RCAS hubs) published in October 2022.

Background

NHS England and UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) Emergency Department Syndromic Surveillance reports from the last two years show that ARI are one of the most common reasons for emergency attendance and admission. Over winter 2022/23 surges in a variety of ARI put significant pressure on the system, with record emergency department (ED) attendances and bed occupancy rates. We need to continue to build capacity and resilience to respond to these pressures.

The Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) programme national specialty respiratory report (March 2021) states that respiratory problems were among the most common reasons for general practice consultations and for acute hospital admissions even prior to COVID-19, and that admissions are growing at around 13% annually.

However, the unprecedented level of ED attendances, as high as 60% above pre-pandemic levels for children and young people aged 2 to10, is not translating into increases in emergency admissions. This highlights the opportunity to reduce pressures in urgent and emergency care (UEC) by strengthening community-based approaches to better support lower-acuity presentations.

Primary care, secondary care and NHS111 will need to work together to support patients to access the right care, at the right time, in the right place. This will help prevent large numbers of children and adults with ARI attending ED, if they are suitable for care in the community.

Aims

An ARI hub model is a system approach that drives a collective objective to provide timely and appropriate care to the population and helps reduce pressure on other parts of the system. The hub model may be best suited to those with acute, episodic needs.

The goals are to:

- Support patients with urgent clinical needs by enhancing same day access to assessment and specialist advice as needed. This includes face-to-face assessment with an appropriate clinician, enabling early intervention and treatment. Access to secondary care support, point of care testing (POCT) or other diagnostics should be considered.

- Seek to reduce ambulance callouts, A&E attendances and hospital admissions for patients who could be appropriately managed in the community.

- Reduce the burden of ARI on general practice, thus freeing up more time for GP practice teams to support patients where continuity of care is most

- Ensure evidence based local or national antimicrobial prescribing guidelines are followed, patient facing resources (TARGET leaflets) are utilized and prescribing data for audit and surveillance is available by differentiating NHS BSA cost centres for ARI hub from GP practices.

- Reduce nosocomial transmission by directing the high expected flow of infectious patients through hubs to avoid infection spread in GP practice waiting rooms and clinics or, where possible, EDs.

- Seek to reduce the health inequalities in outcomes for ARI by providing an accessible and equitable service to support same day access (with consideration given to the location of these services). This approach would support the Core20PLUS5 approach for tackling health inequalities and provision of inclusive services.

- Provide an opportunity for portfolio integrated care working and training for staff at system level that may help with staff development and retention. This could include optimising existing workforce opportunities to support delivery; for example, harnessing the clinical roles recruited through the Additional Reimbursement Scheme (ARRS), such as paramedics, utilizing other available healthcare professionals and draw on non-clinical roles to support effective running of the hubs.

We recommend that where implemented, an ARI hub local evaluation should be undertaken to demonstrate the outcomes, support the development of an evidence base and ensure sustainability of services.

Potential models

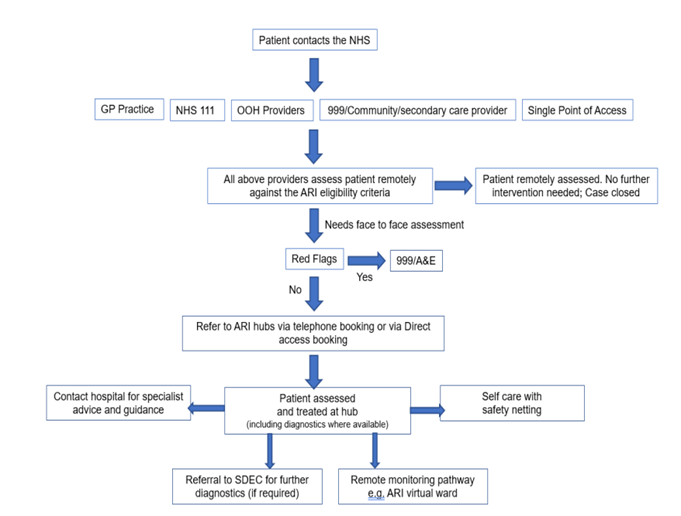

Areas may design their pathway in different ways, depending on local circumstances and need. The below example ARI pathway is for illustrative purposes only.

Image text:

Patient contacts the NHS:

- GP practice

- NHS 111

- OOH providers

- 999/community/secondary care provider

- Single point of access

All the above providers assess patient remotely against the ARI eligibility criteria:

- Patient remotely assessed. No further intervention needed. case closed OR

Needs face to face assessment:

- Red flags – Yes – 999/A&E

- Red flags – No – refer to ARI hubs via telephone booking or via direct access booking

Patient assessed and treated at hub:

- Contact hospital for speciality advise and guidance

- Self care with safety netting

Referral to SDEC for further diagnostics (if required).

Remote monitoring pathway e.g ARI virtual ward.

ARI hubs build on the experience of hot hubs (delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic) or on existing models for respiratory infections in various systems. Systems will already have significant experience and any model should arise from that local intelligence, capacity and infrastructure.

The inclusion criteria should be adults and children with acute respiratory symptoms, most likely due to infection (eg bacterial or viral infections including COVID-19, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza), who have been identified through an initial remote/triage consultation as requiring face-to-face assessment but not hospitalisation. Consideration will need to be given to those more complex patients who may benefit from continuity of care in their general practice setting.

The main referral routes are likely to be GP practices by local agreement; this may be with direct booking by non-clinical roles to reduce pressure on clinical staff and improve efficiencies, NHS 111/ clinical assessment services (CAS), ambulance clinicians and community pharmacists. Where integrated care co-ordination hubs (ICC)/single points of access (SPOA) are available, these should be utilised, where appropriate, to support timely referral and urgent assessment. Consideration may also be given to receiving patients who are referred by other primary care services like community pharmacy, community health services, secondary care or ambulance services, and have been clinically assessed and identified as requiring an urgent follow-up but not an emergency admission.

For assessment and initial management of ARI patients, NICE guidance for suspected acute respiratory infection should be followed. Face-to-face assessment may include diagnostics where available such as point of care testing (POCT), to support clinical decision making and avoidable hospital attendance. Referral to same day emergency care (SDEC) services may also be utilised to support further diagnostics where required. This may be followed by advice, treatment, follow-up appointments or monitoring as required, such as referral to an ARI virtual ward. Once established, subject to capacity, hubs could evolve to include assessment of other acute infections or conditions as per locally agreed pathways. Following a consultation, effective communication back to the patient’s general practice will be required.

The existing National infection prevention and control guidance for NHS healthcare staff of all disciplines in all care settings would apply. ARI hubs could help reduce the risk of infection spread through reducing the footfall in A&E and primary care.

Governance

Legal responsibility, including to ensure appropriate clinical governance, remains with the relevant provider. Each integrated care system (ICS) should have a named person responsible for the establishment of the service in their area. ARI clinical, governance and administrative responsibilities can be provided by any appropriately trained person and best use of resources should be made.

Access arrangements and opening hours for ARI hubs will need to be locally agreed based on prevailing need, and local arrangements made for out-of-hours cover.

The ARI hub should be led by a named clinician.

Additional information

Data

Along with local data, a range of nationally available statistics and interactive toolkits/dashboards are available that can inform planning.

Each resource has its own strengths and limitations but taken together they can give an indication of changes in ARI trends, insight on where ARI demand may be highest and how rates vary across population groups.

Key resources available on NHS England’s ARI Hubs site on the FutureNHS Collaboration Platform:

- An ARI dashboard that is currently updated weekly: monitoring latest ARI trends (primary care, 111/999, A&E) using a range of data sources

- ARI A&E attendance tool. An interactive spreadsheet showing ARI attendances at region, ICB and provider level.

- ARI attendance rates by deprivation. An interactive spreadsheet showing data at ICB, local authority and ward level. This can inform ICBs on where to locate ARI hubs, both for impact on ED attendances but also to improve health inequalities.

Learning resources and guidance

1. Advice, guidance and training materials, including example standard operating procedures (SOPs), triage tools, safety netting and recordings from communities of practice sessions and ARI hub models are available on the NHS @home FutureNHS platform.

2. Respiratory Surge in Children – elearning for healthcare (e-lfh.org.uk)

4. Healthier Together Bronchiolitis Pathway

5. Course: TARGET antibiotics toolkit hub | RCGP Learning

Case studies

Sandwell Paediatric Respiratory hub service model

Aim

This paediatric respiratory hub was shortlisted for the HSJ Patient Safety awards in 2022. It was established to manage winter pressures and address the concern about same day paediatric care in primary care. The triple aim of the service was improving the quality of childhood acute illness management in primary care; reducing A&E attendance and acute admission for children; supporting general practice with increased capacity in primary care.

Processes and staffing

The service was hosted by a primary care network in Sandwell, with full access to patient medical records, providing face-to-face assessment of patients and onward referrals via an existing single point of access (SPOA) to see children with potential infectious illnesses (including RSV, bronchiolitis and COVID-19) in January 2022.

The hub ran from 1-6 pm with up to 40 slots available per afternoon. Two GPs offered 15 minute appointments and were supported by one administrative staff member. Some of a practice manager’s time was also allocated to book staff, update clinical rotas and add the clinics to the relevant system, eg system 1/EMIS.

Eligibility criteria included children aged 12 years or under who presented with acute breathing symptoms, including shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, cough (productive or non-productive) or wheeze and symptoms of infection.

Outcomes

The experience of the service and quality of care provided was extremely positive and analysis from March 2022 demonstrated that of 1,098 patients seen, <0.72% (n=8) were referred to A&E and 0.63% (n=8) were referred to a paediatric assessment unit. The estimated savings from the hub were approximately 35%, with hub appointments costing £43 in comparison to £121 for an A&E appointment.

Dudley Combined Model (children and young people)

Aim

Dudley Access Hub is a model for children and young people that combines a respiratory hub with additional extended hours primary care appointments. This provides 324 more face-to-face GP appointments each week across Dudley place level serving all six primary care networks. The service is integrated with the Urgent Treatment Centre (UTC), which is able to book directly, and 111 redirects patients via telephone.

Processes and staffing

Staffing ratios are either two GPs or one GP and an advanced nurse practitioner providing urgent same day appointments, two reception staff and a hub manager, and is mainly staffed by locum GPs covering. Most staff are either permanent primary care locums or staff already employed within GP practices within the area. The hub prioritises paediatrics between 1 and 6 pm.

Outcomes

Key successes include building relationships with partners and support to relieve pressures across primary and secondary care, preserving workforce capacity. Outcomes of the service include:

- 95% of people reported that if the service were not available, they would have presented at the UTC

- an average 88% utilisation rate with attendance rates at 94% and DNA rates 6%

- 72% of referrals come directly from GP practices, 20% are redirected from 111 and 8% are redirected from UTC

- 99.6% of referrals have been appropriate for the service

- age profile: average 44% under 16, 47% aged 16–64 and 9% aged 64 and over

- average 90% of people are discharged home, 5% required follow-up with their own GP, only 5% required admission to hospital

- 84% of people were seen within 15 minutes of arrival at the hub

- patient feedback very positive, of 569 responses to date, 96% rated their experience as good or very good.

The North Hants Winter Assessment Hub

Aim

The service was launched in November 2020 for patients (adults and children) with fever or respiratory symptoms who required a face-to-face assessment following an initial triage. It was run by a multidisciplinary primary care team, working closely with colleagues across secondary, community and urgent care. It was co-located with a COVID Oximetry @home service, which allowed remote monitoring of high-risk patients with COVID-19 to identify early patient deterioration and provide timely escalation for cases of silent hypoxia, while reducing the burden on secondary care.

Processes and staffing

This hub was formed by a collaboration of six primary care networks (PCNs) covering a population of 230,000 and operated from November 2020 to May 2021. Staff including GPs, advanced nurse practitioners, paramedics and healthcare assistants were seconded from across the PCNs, with four clinicians seeing up to 80 patients per day.

Patients were referred into the service from individual practices following triage, and from the community nursing team, emergency department and the ambulance service. A total of 4,623 patients were seen over 6 months, and 243 (5.26%) were admitted to hospital following this assessment, The remainder were managed safely at home, with support from the COVID Oximetry @home service where appropriate. The hub also included development of loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) point of care assays to confirm COVID-19 diagnosis in patients presenting with acute respiratory infection. Remote monitoring was utilised where required for high-risk patients with COVID-19, supported by pulse oximeters. This was again collaborative, and we worked with the voluntary sector to support vulnerable patients at home.

Outcomes

Patient feedback was extremely positive for this service; 93.3% of respondents would recommend it to others.

Patients confirmed with acute COVID-19 infection were analysed over this time period and those who were assessed/monitored in the hub compared with those who were not. There was a significant association between COVID Oximetry @home and better patient outcomes; most notably a reduction in the odds of hospital lengths of stays longer than 7, 14 and 28 days, and 30-day hospital mortality.

Clinician feedback was also positive. Collaboration resulted in stronger relationships across our local delivery system, between the six PCNs but also across primary, secondary and community care.

Publication reference: PRN00802