What is the purpose of this framework?

This framework should be used by integrated care boards (ICBs) to support the commissioning of high-quality services for children and young people with cerebral palsy. It aims to simplify and summarise existing guidance and help systems identify population need through data. It also highlights examples of best practice.

Cerebral palsy is the most common childhood onset disorder of movement and posture. As a chronic condition, the challenges remain throughout adult life.

Early assessment and intervention can improve developmental outcomes for children and young people with cerebral palsy. Any delay can worsen life-long function, increase secondary complications and decrease clinical wellbeing. It can also lead to the need for more invasive orthopaedic interventions later in childhood, requiring costly prolonged admission and rehabilitation. As a direct result of delayed assessment and intervention, children and young people and adults with cerebral palsy often experience diminished participation and quality of life. This commissioning framework for ICBs, and its focus on early identification and intervention to prevent secondary complication, is supported by the 2025/26 priorities and operational planning guidance.

In addition, when trying to access health services, these children and young people and their families and carers face a system that is fractured, complex to navigate and often uncoordinated. Drawing on these experiences, as well as evidence from clinicians and other professionals, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Cerebral Palsy are calling for measurable improvements to be made to the services.

To support ICBs improve care, NHS England has worked with key stakeholder organisations, including children and young people and their families and carers, to ensure that the recommendations made within the framework align with their feedback.

The scope of this work includes children and young people with a cerebral palsy diagnosis aged 0 to 18, including those in neonatal care and in the transition period to adult services. This is a particularly vulnerable patient cohort who have so far received inequitable access to care.

This work does not include neurodevelopmental conditions beyond cerebral palsy, maternity and prevention, or adults living with cerebral palsy, though the principles may still apply to people of all ages.

While this framework focuses on children and young people with cerebral palsy, it is hoped that learning from developing and implementing this framework could be extended to address broader conditions, including neurodevelopmental needs and care requirements of children and young people with other complex conditions.

What children, young people, parents and carers want from their care

1. NHS England has engaged with a range of children and young people and their parents and carers with the help of our voluntary sector partners. The views obtained from these sessions are outlined below:

| What we have heard… | What action we need to take… |

|---|---|

| I find it difficult to keep track of and navigate all the appointments… | ICBs should ensure every child or young person is assigned a named care co-ordinator or key worker to support access to services through a co-ordinated care pathway. |

| I feel alone and that no one is listening… | ICBs should work with partners in the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector to obtain the views of local children and young people with cerebral palsy and ensure that key partners are adopting the principles of personalised care. |

| I thought my child was missing development milestones and was told to wait longer … | Our guidance highlights the importance of establishing pathways that are focused on early identification. ICBs working in this area should be underpinned by five key principles. We also outline key factors to help commissioners better understand the local needs of children and young people with cerebral palsy and to put in place services that better meets the local need. |

| I know that good therapy is important but find it hard to access it so have had to pay for private care … | Regions and ICBs should work together to offer an accessible local service that includes early access to therapy, suitable equipment and other crucial interventions for improving care. |

| It is unclear what transition to adult services means for us | Regions and ICBs should have a co-ordinated pathway of care across the whole system, including developing transition pathways from local and specialist teams to young adult and lifespan services. Children and young people and their parents and carers should be consulted and involved in key decisions made throughout the transition period. |

2. A more detailed summary of the views gathered as part of this engagement exercise can be found in appendix 1.

Background

3. Cerebral palsy affects approximately 1 in every 400 children in the UK, with an overall prevalence of 2-3.5 per 1,000 live births. This amounts to approximately 30,000 children aged 0 to 16. Approximately 12,000 to 15,000 of these children are classified as being on the more severe end of the spectrum, meaning they are not independently mobile and are at level IV or V of the Gross Motor Function Classification System.

4. Nearly all individuals with cerebral palsy will have at least 1 comorbidity:

- 1 in 2 has a learning disability, and 1 in 4 has a severe learning disability

- 1 in 2 has problems with communication, and 1 in 4 is unable to talk

- 1 in 2 has feeding difficulties

- 1 in 2 has a visual impairment

- 1 in 3 has epilepsy

- 20% to 30% have behaviour difficulties, alongside an increased prevalence of mental health issues

5. High-quality clinical care for children and young people with cerebral palsy involves:

- early intervention and holistic support from relevant professionals within multidisciplinary teams, up to and including the time of transition to adult services

- managing potential comorbidities and minimising the risk and effects of secondary musculoskeletal deformities, especially hip displacement, joint contracture and spinal scoliosis

Case for change

6. We know that many children and young people and their families and carers face challenges around early recognition of cerebral palsy. This causes problems accessing early intervention and support to enable the lifelong management of their condition. As a result of this delay and lack of co-ordinated care, children with cerebral palsy often experience a diminished quality of life, which has negative impacts on the overall wellbeing of their families.

7. An increasing number of children are not being seen by tertiary healthcare professionals until they are of school age, as they are not being diagnosed with cerebral palsy through existing screening processes or are refused further assessment when their parents express concerns. The All-Party Parliamentary Group for cerebral palsy advised that non-specialist health professionals and the public need to be made aware of early warning signs of cerebral palsy.

8. Children and young people with cerebral palsy are vulnerable to a variety of medical and surgical conditions that can affect the wider population. However, these conditions can be more difficult to diagnose and manage in this cohort of patients.

9. There are health disparities among children and young people with cerebral palsy, both in terms of prevalence and severity. Research shows a link between lower socioeconomic status and an elevated risk of cerebral palsy. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognises that children and young people with cerebral palsy have an increased risk of mental health problems due to several factors that have a marked impact on their quality of life and challenges of care. There is, however, minimal evidence in this area due to a historical lack of focus on this patient cohort.

10. Access to care for children and young people with cerebral palsy and their families varies significantly, particularly in getting appropriate care from trained clinicians locally. For instance, when it comes to preventing hip dislocation and displacement, a common issue in children with cerebral palsy, 8 out of the 42 ICBs do not have a provider overseeing the care for people with cerebral palsy. Some providers do not have a formal care pathway for children and young people with cerebral palsy, with some still using a generic pathway for children with physical disabilities. This situation puts this cohort of patients at risk of not receiving early intervention, potentially leading to a deterioration of symptoms.

11. In addition, in areas without a provider overseeing care for children and young people with cerebral palsy, patients might need to travel significant distances to access specialist care. This reflects the need for improved accessibility and more local interventions for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

12. Children and young people with cerebral palsy and their families are faced with numerous challenges when trying to access the care that they need. Several reports have recognised 4 main challenges:

- co-ordination of care across specialist providers and community settings to enable early identification and intervention by multidisciplinary teams

- training and education of staff across the pathway, including health visiting and general practice

- robust data collection for service improvement

- transition of care into adult services

5 key principles to underpin joint working

13. key principles should underpin joint working across an integrated care partnership footprint and multiple systems to support children and young people with cerebral palsy who may have multiple needs.

- There should be a focus on early identification of infants at risk of cerebral palsy and ensure access to early intervention, particularly providing targeted assessment and therapies by a multidisciplinary team using equipment that is fit for purpose. This will maximise individual function, mobility, communication and healthcare efficiency.

- The workforce supporting children, young people, and their families should be centred around a local integrated core multidisciplinary team, closely consulting with regional centres of clinical excellence, which provide expertise and enable access to wider services.

- Long waits should be avoided, including by co-ordinating care pathways to improve access to multiple services in a single clinical visit. Where possible, care should be provided closer to home and virtual appointments used where they are in the patient’s best interest.

- High-quality, safe care should be personalised for the needs of the child or young person. We should aim to keep children and young people in school, where possible. We should respond to their individual needs through working with families and naming a key worker or care co-ordinator to support and co-ordinate services for the child and family.

- ICBs should work collaboratively across an integrated care partnership footprint with local authorities, education and VCSE partners to support children and young people with cerebral palsy and their families, minimising inequalities in their communities. Clear pathways of clinical provision and responsibility should be in place within the system and across the region as required.

Cross system working is required to provide a holistic care offer

14. Cerebral palsy affects people in different ways. Some children and young people may have a range of wider conditions beyond movement and postural challenges that need support (as detailed in appendix 3).

15. Knowing the severity, topography and motor type of cerebral palsy is the starting point to co-ordinate care and plan treatment, with careful consideration of holistic support for comorbidities.

16. Integration and joint working are crucial for holistic care for children with cerebral palsy. Key system partners, including a diverse range of professionals involved in planning and delivering care for a child or young person with cerebral palsy, should feed into a single care plan to enable effective care planning. Similarly, an Education, Health, and Care Plan (EHCP) could serve as a collaborative tool, ensuring a unified approach between healthcare and education.

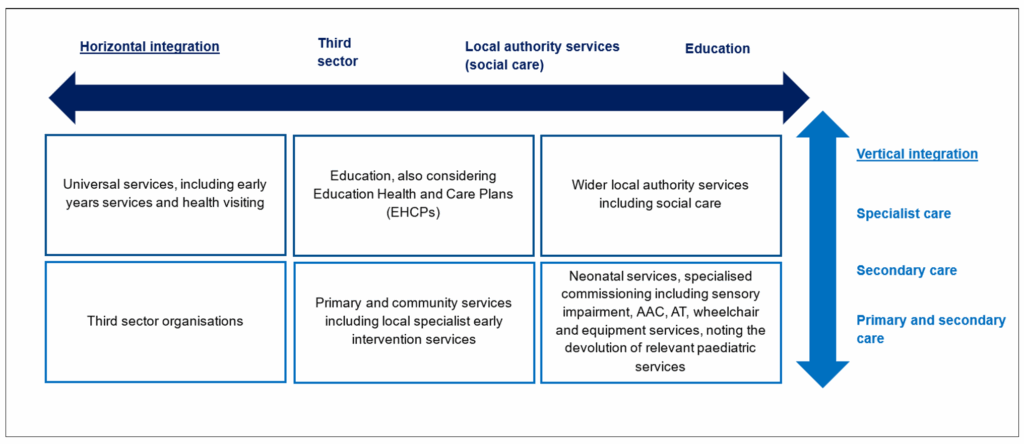

17. Figure 1 summarises the key partners that should be involved in planning and delivering care for children and young people living with cerebral palsy, while appendix 4 outlines the range of professionals that should be involved in planning and delivering care for children and young people living with cerebral palsy.

Figure 1: Key partners to consider when planning and delivering care for children and young people with cerebral palsy

Figure summary: The partners are divided into the following groups: universal services including early years services and health visiting; education, also considering Education Health and Care Plan; wider local authority services, including social care; third sector organisations; primary and community services, including local specialist early intervention services; and finally, neonatal services and specialised commissioning, including sensory impairment, Augmentative & Alternative Communication Technology, Assistive Technology and wheelchair and equipment services.

The diagram shows how these groups will need to work across the system taking both a horizontal and vertical approach. Horizontal integration consists of the third sector, local authority services (for example, social care) and education working together, while vertical integration consists of specialist care, secondary care, and primary and community care.

18. Multidisciplinary intervention from the time of recognition is imperative in all areas of health and development. The management of cerebral palsy requires a 2-pronged approach:

- optimising movement, posture and function, while minimising potential secondary musculoskeletal deformity

- recognising and intervening to address the developmental and clinical comorbidities that are associated with cerebral palsy

19. ICBs should commission services to support early assessment, early intervention, and access to specialist care for children and young people living with cerebral palsy. This should include ensuring local neonatal services have access to allied health professional services, as outlined in the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) This can be done in collaboration with wider system partners, including place-based partnerships, provider collaboratives and VCSE organisations.

Local service offer within an integrated care partnership

20. To ensure children and young people with cerebral palsy have equitable and co-ordinated access to care, ICBs should ensure the following local services are provided. Furthermore, some ICBs will need to work across multiple footprints in the wider region to ensure that there are clear pathways of care provided in tertiary centres.

ICB local level

1. Education for health professionals

- Training should be provided for:

- health visitors and general practitioners

- allied health professionals

- community and general specialist practitioners

- Training should cover:

- early diagnostics and assessment of cerebral palsy, including red flags of development and pathways to paediatric services

- areas of specific clinical and developmental challenges associated with cerebral palsy

- lifelong support and care pathways within ICBs

2. Early diagnosis

- Following discharge from neonatal intensive care units, infants at risk of developing cerebral palsy (as outlined in appendix 6) should have developmental assessments up to the age of 2 years. This involves clear pathways of communication between specialist and regional neonatal and neurodisability teams and local multidisciplinary teams in child development centres or their equivalents.

- There should be routine national developmental screening via GPs and health visitors. There should be early referral to local child development team when red flags are found.

- Multidisciplinary community services should be provided for rapid assessment and access to brain and spine MRI (regional pathways), especially if there is no neonatal neuroimaging.

3. Early intervention

Co-ordinated and wrap-around care should include:

- community paediatricians with the knowledge and skills related to supporting children and young people with cerebral palsy and their families

- developmental multidisciplinary teams for early therapy intervention to maximise developmental potential and outcome

- interdisciplinary and family support and liaison with wider system partners in social services and education

- primary care teams, GPs and health visitors to provide routine medical and universal care

Across all spatial levels

4. Co-ordinated pathways of care across the whole health system should include:

- multidisciplinary teams involved in developmental assessment, monitoring and therapy interventions within local community services – this may be within a child development centre

- regionally commissioned services in neurodisability, movement therapies, feeding and communication, neurology, orthopaedics, spinal teams, and other co-morbid clinical areas

- relevant national specialist services, for example, neurosurgical interventions

21. Taking a collaborative approach could improve the interface between care providers, support local teams, reduce duplication and ensure equitable service across regions for all clinical and developmental needs. Appendix 5 details a non-exhaustive list of specialist teams, pathways and services that ICBs should ensure there is effective collaboration.

22. To support continuity of care, it is also important that ICBs develop appropriate transition pathways from local and specialist teams to adult and lifespan services to support a coordinated transition to adult services.

Key enablers for commissioning high-quality services for children and young people with cerebral palsy

23. Key enablers will help ICBs improve quality of care and experience for patients.

- A cerebral palsy data dashboard can drive local area improvement and service design, ensuring ongoing routine data collection and monitoring of cerebral palsy data. This will bring together existing hospital-based data and data from the Cerebral Palsy Integrated Pathway (CPIP), including information on hip displacement and other comorbid, developmental and functional needs. It will also encourage uptake and reporting of community-based cerebral palsy data. Over 2025/26 NHS England will require selected ICBs to use the data dashboard to baseline their population to understand population activity and need. These ICBs will use local intelligence to understand what patient pathways are currently in place and to understand where there are gaps in service provision both within the ICB footprint and across wider system partners. The dashboard will be published on the new NHS England power BI platform, access will be available on request to the national Children and Young People Transformation team.

- Adopting personalised care principles and making personal health budgets and personal wheelchair budgets available will enable tailored and flexible care plans for children and young people and their parents and carers. An example showing the potential cost savings from investment in appropriate equipment is detailed in appendix 8. In addition, ICBs should work with key partners to obtain the views of children and young people with cerebral palsy to ensure that commissioned services are informed by need and delivered flexibly.

- Many children and young people living with cerebral palsy have multiple needs. A named care co-ordinator or key worker can help support families to navigate the health, care, education and wider system, while preventing duplication of appointments. This approach would enable care to be wrapped around the child or young person and their family or carers.

Next steps for ICBs

24. The NHS England Children and Young People’s Transformation Programme plan to work with volunteer ICBs to carry out a baselining exercise over 2025/26, using this framework as a benchmark for standard of care. It is anticipated that this will include:

- using the data dashboard, CPIP and local intelligence over 2025/26 to understand local children and young people cerebral palsy activity

- using local intelligence to develop an outline of existing local patient pathways within the system for children and young people with cerebral palsy and identify gaps in service provision

- supporting volunteer ICBs to implement the three key enablers specified in this framework to improve quality of care

25. This exercise will help bring to light the services required for children and young people within their system and, where possible, across the wider regional landscape. This will also take into account services provided by wider system partners. Learning from this exercise will be shared more widely to support scale-up.

26. Commissioners may wish to establish comprehensive training and education programmes for a variety of professions involved in patient care, including allied healthcare professionals, health visitors, general practice staff. This should outline best practice and responsibilities of professionals across the patient pathway. Specific areas of focus should include:

- co-ordinating training for the follow-up of high-risk infants post-special care baby unit

- developmental follow-up of all children by health visitors and general practice staff

- the involvement of community paediatricians

- local pathways for initiating referrals and assessments, emphasising the importance of supporting children and young people with cerebral palsy and their parents and families

Appendix 1: Summary what children, young people, parents and carers would like from their care

The below is a summary of a series of engagement sessions with children and young people with cerebral palsy and their parents and carers:

Summary of children and young people’s views

- Accessing services and support varies, especially for those with milder conditions, elevating the risks of receiving a late diagnosis, a misdiagnosis, or delayed access to appropriate intervention. This highlights the need for more equitable support across the board. Additionally, there was limited availability of appropriate support and equipment for students with cerebral palsy with complex needs in educational settings, such as schools and universities.

- Some children and young people experienced delays in receiving a cerebral palsy diagnosis, impacting the timely initiation of crucial services. The challenges extended beyond diagnosis, with a significant reduction in support after the age of 16, leaving a profound sense of abandonment.

- Children and young people expressed that they often do not receive personalised care, frequently leading to them receiving the wrong equipment or wrong intervention, further worsening their symptoms.

- Advocacy and increased awareness among professionals and support networks for children and young people with severe cerebral palsy is needed. Positive impacts were noted where a supportive social worker successfully advocated for additional support hours. Community building with children and young people with similar conditions was flagged, emphasising the importance of supportive networks.

- Children and young people expressed that they faced difficulties in accessing appropriate care that meets their needs, local to where they live and in a timely fashion. This often necessitates travel “out of area” or accessing private healthcare.

- Co-ordination of care is fragmented. Children and young people expressed a need for a key point of contact to better co-ordinate services. Positive experiences were noted when referred through a specialist school.

- Transitioning from paediatric services to adult services could be more streamlined. Children and young people expressed that they are often not listened to or included in key decisions before and during the transition process, even though they had the capacity to make decisions. those

Summary of parent and carer views

- Parents emphasised the importance of conducting assessments in an environment familiar to the child. Spending time with the child is crucial for accurate assessments. Some suggested a “pick and mix” approach that allows families to access the right professionals and services based on their unique needs.

- Due to challenges in accessing NHS services, parents flagged that they are seeking some of their care privately; this often comes with a financial burden.

- Parents of children with cerebral palsy encounter a series of challenges due to the delayed diagnosis of their child’s condition. Parents expressed concerns about healthcare providers not providing enough information about risk factors and red flags to watch for during the early stages of their child’s development. They also highlighted the potential for health visitors to play a more dynamic role in early identification, monitoring child development and identifying missed milestones.

- Parents highlighted disparities between the quality of therapy support provided in the hospital setting compared to the community. They reported long waiting lists for community therapies and expressed concerns about the inequity of services. They suggested creating a template of possible services for parents to navigate the complex landscape.

- Parents expressed that the transition period is challenging for parents and stressed the need for extra support during this phase. Parents also face difficulties in obtaining the necessary support through an EHCP. Paediatricians and cross-sector services play a vital role in supporting the child’s care and development.

- Parents stressed the difficulties in accessing necessary support and information before an official diagnosis is made. Many wanted additional support during the waiting period for diagnosis.

- The parents advocated for the role of a dedicated care co-ordinator or key point of contact who could guide them through the healthcare system. They also highlighted the need for a more comprehensive understanding of personalised care, potentially involving budgets for equipment and therapies. Community paediatricians play a significant role in co-ordinating care and providing consistent support.

Summary of care professionals views

This framework has been developed with active involvement from clinicians from our national Cerebral Palsy Task and Finish group, representing key professions that are involved in care provision for children and young people with cerebral palsy. This framework has also considered the points made in the All-Party Parliamentary Group paper, including the views of clinicians (summarised below):

- Clinicians strongly recommend prioritising early intervention for infants with cerebral palsy during the formative stages of brain development. It’s imperative to act promptly, as cerebral palsy displays high responsiveness to early interventions. Any delays can result in substantial costs, both in terms of the child’s wellbeing and the healthcare system.

- Streamlined care pathways need to be developed to prioritise children’s wellbeing. This includes implementing NICE guidelines as a minimum standard and reducing referral-to-treatment timescales for rapid intervention.

- Clinicians advocate for a national surveillance programme that employs MRI scans, Prechtl’s General Movements Assessments, and neurological exams to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in at-risk infants.

- Clinicians have stressed the need for improved data collection for better service planning and the establishment of a national cerebral palsy register. This register would comprehensively record incidence, diagnosis, medical history and outcomes, aiding research and early intervention monitoring.

- Support should be strengthened for families coping with a cerebral palsy diagnosis. This should involve assigning dedicated “partners” within child development teams and providing comprehensive training to non-specialist health professionals for early signs recognition.

- Referral-to-treatment timescales for cerebral palsy should be tightened and minimised to ensure timely access to interventions and services.

- Healthcare services should be required to implement the NICE guidelines and quality standards as a minimum. Practitioners and clinicians should be fully aware of their responsibility for prompt referral to expert multidisciplinary teams. Care pathways should include agreed and audited quality standards.

Appendix 2: Synthesis of available guidance and clinical standards

There are key elements of the patient pathway. Each has relevant guidance, including clinical best practice.

There are shared commissioning responsibilities across the pathway, with prevention and early identification a shared responsibility across local authorities and NHS services. The remainder of the pathway is the responsibility of the NHS.

ICBs are responsible for the devolution of specialised services, the management of comorbidities, including general orthopaedic or specialist surgery. The information below summarises key clinical guidance, classification systems and commissioning guidance. Relevant links are provided for ease.

Summary of key guidance

Prevention

- NG25: Preterm labour and birth – NICE

- NG72: Developmental follow-up of children and young people born preterm – NICE

Early identification

- NG62: Identifying and diagnosing cerebral palsy in under 25’s – NICE

- QS162: Cerebral palsy in children and young people – NICE

- Cerebral palsy developmental stages – Action Cerebral Palsy

- Guidance around early diagnosis of cerebral palsy – American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine

- Early intervention programmes for infants at high risk of atypical neurodevelopmental outcome (EiSMART)

- Early support for cerebral palsy – Council for Disabled Children

- Postnatal care – NICE

- Developmental follow-up of children and young people born preterm quality standards – NICE

Diagnosis

- NG62: Identifying and diagnosing cerebral palsy in under 25’s – NICE

- QS162: Cerebral palsy in children and young people – NICE

- Chronic Neurodisability: Each and Every Need – National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death

Early Intervention

- NG62: Identifying and diagnosing cerebral palsy in under 25’s – NICE

- QS162: Cerebral palsy in children and young people – NICE

- UK Pathway for hip surveillance to prevent hip dislocation – Cerebral Palsy Integrated Pathway – CG145 recommendation 1.1.17

- CG145: Spasticity in under 19s: management – NICE

- Poster – supporting parents and high-risk infants during a disrupted transition to parenthood (EiSMART)

- Guidance on hip surveillance in cerebral palsy – American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine

- Disabled children and young people up to 25 with severe complex needs: integrated service delivery and organisation across health, social care and education – NICE

Treatment including complications

- NG62: Identifying and diagnosing Cerebral palsy in under 25’s – NICE

- Report on paediatric trauma and orthopaedic services – recommendation 15 – Getting It Right First Time

- NG43: Transition from children’s to adult’s services for young people using health or social care services – NICE

- NG119 Cerebral palsy in adults – NICE

- Guidance for Commissioning Augmentative and Alternative Communication Services and Equipment – NHS England

- Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years – GOV.UK

- Disabled children and young people up to 25 with severe complex needs: integrated service delivery and organisation across health, social care and education – NICE

Classification systems

- Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) – Cerebral Palsy Alliance Research Foundation (CPARF)

- Manual Ability Classification System

- Communication Function Classification Systems

- Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System – Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust

How the Cerebral Palsy Integrated Pathway (CPIP) can support better care

The CPIP has been developed in line with international guidelines to provide a high-quality standardised programme to monitor and prevent musculoskeletal problems among children with cerebral palsy.

Evidence from Sweden has shown that hip dislocation in cerebral palsy is preventable by patients having regular, standardised physical and radiological assessments from an early age. This early intervention reduces deformity, pain and the need for invasive surgery.

A review concluded that under conservative assumptions and without including quantified quality of life impacts for the patient or their families, CPIP has a net positive financial benefit to the system each year over the course of childhood for those with more severe cerebral palsy. For children with mild cerebral palsy, the pathway has a net financial benefit to the system, assuming that there is already some spend on existing physiotherapy provision. These findings are based on evidence and costs, including:

- in Sweden, the number of children with cerebral palsy treated with orthopaedic surgery for contracture or skeletal deformity fell from 40% to 15%, following implementation of CPIP

- a 1 hour one-to-one session with a paediatric physiotherapist costs £142, whereas an outpatient appointment with a consultant paediatric orthopaedic surgeon costs £212

- physiotherapy assessments for a child with cerebral palsy specified by CPIP between the ages of 2 and 18 would cost £4,000 over the course of a childhood, whereas hip surgery for a child with cerebral palsy costs on average £7,000

The expectation is that every community, secondary and tertiary provider providing care to children with cerebral palsy will subscribe to the CPIP database, and that every child with cerebral palsy will be registered on the database (following a multidisciplinary team review).

Support around subscribing and registering can be sought from the CPIP Network and the relevant CPIP regional network. The initial CPIP training requires 2 2-hour sessions but there is no direct financial cost to the provider in joining the database. Short training update sessions are then required annually. The following case study summarises how implementing CPIP can enable early intervention and prevention further decline in the health condition of a child or young person.

Best practice example: early intervention in muscle tone therapy

Case study and ambition

Early intervention, enabled by CPIP assessment, to limit the aggressiveness of further intervention for children and young people with cerebral palsy by adopting a more conservative approach.

What was the issue?

- Huge variability and inequity in accessing serial casting for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

- Yearly CPIP assessments helped identify a child’s need for botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) injections by identifying the presence of spasticity and confirming a deterioration in the child’s range of motion.

- The local community team also offered a period of serial casting, a procedure that involves the application of a fiberglass cast with padding to hold a part of the body in a position to promote prolonged stretching and help improve their range of movement. This is less invasive and more cost effective than standalone BTX-A injection treatments. There is, however, variation in the availability of serial casting nationally as this intervention is not always offered as a standard treatment across community teams. It is also not usually commissioned as a core and standard service by ICBs.

Solution

- Conduct regular CPIP assessments using the CPIP tool, with support of senior team, to monitor a child’s progress.

- Community physiotherapist teams should offer serial casting as a standard, non-invasive and conservative treatment option.

- Ensure that community physiotherapy teams are adequately staffed and have the necessary resources and training to perform assessments and interventions effectively.

- Promote education and awareness of the benefits of early intervention and CPIPs in managing cerebral palsy.

Impact

- Early intervention can prevent muscle contractures, improve mobility and enhance physical wellbeing in children with cerebral palsy.

- Serial casting will help reduce long-term complications, including the need for orthotic and orthopaedic treatments. It will also reduce a decline in mobility in children with cerebral palsy.

Proper implementation of CPIPs can lead to more targeted and effective care for children with cerebral palsy.

Challenges

- Data collection and management to ensure accurate tracking of a child’s progress and early identification of potential issues.

- Limited staffing and funding for community teams to perform assessments and offer interventions such as serial casting.

- Some community teams lack access to proper training and resources for completing assessments that could enable early intervention.

- Senior team’s decision to endorse CPIP is usually influenced by varying perspectives on the value of CPIPs.

Lessons learnt

- The importance of regular cerebral palsy assessments and data collection to track changes and inform treatment.

- The significance of the severity of the condition in understanding the natural history of cerebral palsy and the need for early intervention.

- The value of education and awareness among health professional in promoting early intervention and CPIPs.

- Identifying and addressing barriers to the adoption of CPIP is essential to ensure compliance.

Appendix 3: Helping commissioners better understand population need

There is no “one size fits all” approach to service provision for children and young people with cerebral palsy. Clinical need of each individual varies. The requirement across the population, however, is consistent.

Knowing the severity, topography and motor type of cerebral palsy are the starting point to co-ordinate care and plan treatment, with then careful consideration of holistic support for comorbidities. The following factors are intended to help commissioners identify the range of resource required to support their populations with cerebral palsy across a spectrum of need.

Commissioning factors related to need

Developmental needs and multidisciplinary care:

- gross motor, tone, movement and posture

- fine motor and learning support

- speech, language and communication needs and swallowing, assistive technology (AT) and augmentative and alternative communication technology (AAC)

- sensory processing impairment, including proprioception and vestibular challenges

- special educational needs and disabilities (SEND)

Physical health needs:

- feeding and swallowing

- sleep

- pain

- spasticity and dystonia (movement therapy)

- bowel and bladder issues

- saliva control

Co-morbidity:

- musculoskeletal and bone health (movement therapy and orthopaedic teams)

- respiratory health

- gastrointestinal health

- epilepsy

- recurrent infection

Mental health needs:

- anxiety

- depression

- increased rates of neuro-behavioural disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity and autistic spectrum disorders

Social complexity:

- understanding the wider family dynamic, including social determinants of health

- effect of cerebral palsy on family and siblings

- barriers to education, travel and socialising

Appendix 4: “The team around the child”

Outlined below is a non-exhaustive list of the range of professionals that should be in place to deliver holistic care and support to a child or young person with cerebral palsy. Together, they form “the team around the child” working to address medical, developmental, educational and psychosocial needs.

In line with national and international guidelines, the local integrated core multidisciplinary team should comprise a variety of key medical and therapy specialists. Clear pathways for more specialist care are key, including co-ordination for interdisciplinary intervention with social services and education.

Relevant professionals and their roles and responsibilities

- Neurodisability paediatrician: Diagnoses and manages medical issues related to cerebral palsy. Provides medical assessments; monitors growth and development; prescribes medications or therapies.

- Paediatric neurologist: Specialises in diagnosing and treating neurological conditions in children. Conducts neurological assessments; orders and interprets diagnostic tests; provides treatment recommendations.

- Community or developmental paediatrician: Specialises in developmental and behavioural issues in children. Evaluates developmental milestones; provides interventions for cognitive and behavioural challenges; offers support for families.

- Paediatric orthopaedic surgeon: Treats musculoskeletal issues related to cerebral palsy. Performs orthopaedic surgeries; manages orthotic devices; addresses bone and joint problems.

- Paediatric physiotherapist: Helps improve mobility, strength and motor skills. Designs exercise programmes; provides gait training; assists in improving balance and coordination.

- Paediatric occupational therapist: Assists in developing skills for daily activities and independence. Offers strategies for self-care; facilitates fine motor skill development; recommends adaptive equipment.

- Speech and language therapist: Addresses communication and swallowing difficulties. Conducts speech and language evaluations; provides therapy for speech and language development; assists with feeding and swallowing interventions.

- Paediatric psychologist: Supports emotional and behavioural wellbeing. Provides counselling for coping with challenges; assesses and treats mental health issues; offers support for parents and caregivers.

- Paediatric nurse: Coordinates care and provides medical support. Administers medications; conducts health assessments; offers education and support to families.

- Social worker: Advocates for the child and family. Coordinates community resources; assists in accessing support services; provides counselling for social and emotional challenges; advocates for educational and social inclusion.

- Special educational needs teacher: Designs and implements educational plans for children with disabilities. Creates individualised education programmes; adapts curriculum to meet specific needs; collaborates with therapists and other professionals.

- Assistive technology specialist: Evaluates and recommends assistive devices and technologies. Identifies technology solutions to enhance independence; provides training on device use; facilitates access to adaptive equipment.

- Care co-ordinator or key worker: Oversees coordination of care across multiple providers and services. Coordinates appointments and services; advocates for comprehensive care; ensures communication among team members.

Appendix 5: Service expectation across regions and ICBs

To ensure fair access to assessments and interventions, ICBs should collaborate to provide various services within their local area or through partnerships with key regional stakeholders. This collaborative approach not only benefits children and young people with cerebral palsy by ensuring that their clinical and developmental needs are met, it also enhances interactions between care providers. By reducing duplication and promoting consistency, this collaboration ensures uniform services across regions, aligning with established guidelines.

Below is a non-exhaustive list of specialist teams, pathways, and services that ICBs should ensure there is effective collaboration. This may require working across a larger footprint to enable access. These include:

- pain, mobility and tone management services to support specialist assessment and interventions for upper and lower limb function

- epilepsy services to ensure effective co-ordination of care for children and young people with a co-morbidity of epilepsy, including those with drug-resistant epilepsy requiring tertiary input

- assistive equipment, including mobility aids, wheelchairs and postural equipment

- paediatric orthopaedic services to minimise the risk and negative outcomes of musculoskeletal deformity and hip dislocation

- endocrinology services to support bone health and reduce the risk of osteoporosis, minimally traumatic or atraumatic fractures

- mental health services to support children and young people with anxiety and depression which may arise from diagnosis or intervention

- gastroenterology and surgical teams to support feeding and gut dysmotility

- augmented and assistive communication technology service to facilitate effective communication for all those with speech and language challenges. This service plays a crucial role in empowering children and young people with cerebral palsy to express themselves

Additional services may need to be commissioned to meet the specific needs of the local population.

Appendix 6: Principles for training, early identification and intervention

NICE recommends that children at increased risk of cerebral palsy – children who have been in neonatal intensive care with any of the outlined risk factors for developing cerebral palsy – should receive an enhanced clinical and developmental follow-up programme by a multidisciplinary team, up to the age of 2 years. Clinicians must be aware of possible early motor features suggestive of cerebral palsy and the most common delayed motor milestones with cerebral palsy to identify and diagnose the condition early.

NICE guidance (NG62) also provides clear “red flags” within normal child developmental assessments in primary care that should ensure early and timely referral to the most local child development centre within the ICB. The responsible clinician should urgently act upon red flags for motor development to ensure an optimal outcome.

However, there are an increasing number of children who are not being identified through existing screening processes and are not seen by tertiary healthcare professionals until they are of school age. The All-Party Parliamentary Group for cerebral palsy advises that non-specialist health professionals and the general public need to be made aware of early warning signs.

The key touch points in the maternity pathway where early identification could happen are outlined below, including the key checks that should be carried out in the first few weeks after an infant is born to help spot the early warning signs of cerebral palsy.

Supporting early identification in the maternity pathway

Routine postnatal and infant developmental care

NICE postnatal care guidelines detail a pathway for mothers and babies that, if implemented correctly, could enable the early identification of cerebral palsy in the first few weeks after birth.

- A first postnatal visit by a midwife should take place within 36 hours after transfer of care from the place of birth or after a home birth. The first postnatal health visitor home visit should take place between 7 and 14 days after transfer of care from midwifery care.

- Healthcare professionals should carry out the NIPE Examination within 72 hours of the birth and at 6 to 8 weeks after the birth. This should include checking the babies’ hands, feet and hips.

- Healthcare professionals should consider giving parents information about the Baby Check scoring system and how it may help them to decide whether to seek advice from a healthcare professional if they think their baby might be unwell.

- Shortly before a baby is born, mothers should be given a personal child health record (PCHR) to record developmental milestones (also known as the “Red Book”). Health visitors should be trained to spot the early warning signs (“red flags” in NICE guideline – NG62) of cerebral palsy that may be recorded in the Red Book.

Enhanced developmental support in neonatal care

Cerebral palsy is rarely picked up at birth, though any child with a recognised impairment of brain development is at high risk. Children at risk of cerebral palsy are eligible for enhanced developmental follow-up and support in neonatal care units.

- NICE recommends that parents or carers of at-risk babies who are eligible for enhanced developmental support are provided with a single point of contact for outreach care within the neonatal service.

- These teams should be available to answer questions about non-acute issues. They should also be available to support parents or carers of at-risk babies who are eligible for enhanced developmental support after discharge and while they are followed up by neonatal services.

For infants and children with, or at risk of, cerebral palsy, early intervention is critical to maximise impact and increase participation and independence

Clinicians and service providers must take advantage of the window of opportunity presented by infants and young children with higher levels of brain plasticity and aptitude for learning new skills (between 0 to 2 years). In line with the Quality Standards developed by NICE, this will require enhanced surveillance of all infants at risk of cerebral palsy, together with better public and professional awareness of the signs of cerebral palsy in infants and young children not identified as at risk at birth.

Children with abnormal motor signs or who are at high risk of developing cerebral palsy should be immediately referred to a local multidisciplinary team. Within this offer, age specific assessments and interventions should be undertaken, including: therapy interventions to prevent musculoskeletal impairments and improve motor skills; cognition; communication; eating, drinking and swallowing and the management of muscle tone.

A comprehensive multidisciplinary approach is recommended at the local service level to best co-ordinate early interventions (as outlined in appendix 4).

Services should also support parents and caregivers to: build relationships with their child; improve participation in interventions; and strengthen parental mental health.

Appendix 7: Best practice examples across key interventions

These examples showcase effective best practices centred around early identification and intervention strategies. They highlight collaboration across multidisciplinary teams enabled by data and the establishment of seamless, robust transitions between service providers.

Best practice example: Creation of a national hip surveillance programme to support early intervention

Case study and ambition

Cerebral Palsy Integrated Pathway Scotland (CPIPS): Creation of a national hip surveillance programme to prevent the occurrence of hip displacement, hip dislocation and associated pain.

What was the issue?

- Children with cerebral palsy developing hip displacement and hip dislocation and the associated pain and need for invasive surgery in Scotland.

Solution

- In 2010, a group of clinicians in Scotland sought collaboration with paediatric physiotherapy colleagues to agree protocols for physical and x-ray examinations, following the Swedish model. Resources and training were developed alongside this to support implementation of a national hip surveillance programme.

- The Cerebral Palsy Integrated Pathway Scotland (CPIPS) programme was formally established in 2013, supported by the Association of Paediatric Chartered Physiotherapists (APCP) Scotland, with funding from the Robert Barr Trust, Brooke’s Dream and the Scottish Government for 3 years.

- All Scottish health board areas continue to carry out annual competency updates, including measuring and clinical reasoning.

- The programme and accompanying database have since been extended to cover the rest of the UK.

Impact

- There are over 2,300 children and young people on the CPIPS database, which is hosted by the Health Informatics Centre at the University of Dundee.

- There are a further 9,800 on the CPIP database in England.

- A peer-reviewed journal article published in March 2020, which analysed 1,646 children, demonstrated that the CPIPS surveillance programme had reduced the prevalence of hip displacement by over half from 10% to 4.5%, and reduced the prevalence of hip dislocation by almost half from 2.5% to 1.3%.

- A separate study, carried out using nearly a decade’s worth of high-quality data in CPIPS, identified the “point of no return”, that is the migration percentage beyond which a hip was almost certain to progress to dislocation. This has been very influential both nationally and internationally, allowing clinicians to intervene at the correct time so children do not receive potentially unnecessary operations while at the same time ensuring that those who need hip surgery receive it before their hips dislocate.

Challenges

- Funding continues through a variety of sources, including charities, pharmaceutical companies and Scottish government grants. Permanent, recurring funding is yet to be secured.

Lessons learnt

- The importance of standardised protocols to ensure that best practice in early intervention can be scaled up.

- The role that a national database or registry can play in supporting research to underpin clinical improvement and patient outcomes.

Best practice example: Improved care coordination enabled by One Single Input at Evelina (OneSIE)

Case study and ambition

One Single Input at Evelina (OneSIE) to provide a child and family-centred service where multiple services are seen in 1 visit.

What was the issue?

- Increasingly complex multi co-morbid patient population in the South Thames Network.

- Attending multiple appointments in outpatient setting was increasing burden of care on the family, including siblings, both financially and mentally. It was also resulting in time away from education.

- Distress of travel, including distance and clinic environment

- Increasing concerns regarding communication between services, causing potential harm within the pathway, and a risk of patients attending more than one specialist unit for their care.

Solution

- Child and family-centred service review rather than service-centred outpatient appointments.

- OneSIE sessions created 1 to 2 times per week, either on site or via Attend Anywhere. A child is reviewed by multiple services in one visit. Child is considered as a potential OneSIE candidate. Administrative support highlights date and time of OneSIE appointment to relevant services. The child attends the appointment either face to face or virtually. After the OneSIE appointment, the MDT meet and create a patient-focussed plan for the individual child.

- Multiple services seen in 1 visit, tailored for individual patient pathway.

- Services provide link clinician for the family.

- Virtual follow-ups between reviews, with appointments co-ordinated where possible.

Impact

- 2 of the 3 appointments can be conducted virtually. In person appointments are coordinated with wider teams. This maximises efficiencies for the trust while minimising travel for the patient and the carbon footprint for the trust.

- The case study estimated that the yearly cost for families to attend clinic appointments is £3500. Reducing the number of visitors families have to make to attend appointments, could reduce these travel costs significantly.

- Minimise time out of work and education for children, young people and their families and carers.

Challenges

- Requires changing established ways of working to ensure better co-ordination between services and specialists. Sometimes, there can be resistance from clinicians and families who may be used to the previous ways of working.

- Requires working with job plans to ensure periods of the week when a variety of services are all available.

Lessons learnt

- The key enablers for implementation are:

- changes in job plans and working across departments

- implementing commissioning models that consider day cases versus multiple outpatient appointments

- potential review of departmental responsibilities to enable cross department support

- role of an admin co-ordinator who can discuss the individual patient pathway with a variety of teams involved and plan services and timings around the patient accordingly

- use of one area as a point of central placement, so the children and families have a base, in this case study, the use of the day unit

Best practice example: Empowering independence – a collaborative approach to tailored mobility solutions for a child with complex needs

Case study and ambition

Whizz Kidz wheelchair service finding the right solution for a child with complex needs.

What was the issue?

- Child A was having difficulty with self-propelling the lightweight active wheelchair due to having upper limb weakness. A wheelchair service therapist and community therapist reviewed the wheelchair set-up, and it was not able to be adjusted to achieve a more optimal self-propelling position. From the assessment, the following options could be considered:

- an alternative manual wheelchair with optimal set up

- a powered wheelchair

- From the assessment, it was decided that the powered wheelchair would be explored.

- Joint funding between the wheelchair service, social care and education can offer features that are not usually available via the NHS.

Solution

- Collaborative work between the wheelchair service and children’s social care and education providers could enable Child A to have the most suitable equipment.

- A powered wheelchair with the ability to grow as required with a riser feature was issued. This enabled Child A to access all areas at school, as well as being able to reach higher surfaces as required.

- The wheelchair has a tilt in space feature to enable Child A to relax within the chair as well as having the ability to change their position to prevent pressure risks. This can be used at home as well as school.

- The wheelchair service is not commissioned to supply the riser function on wheelchairs. This is not seen as a clinical need but a social need to enable the child to access their environment. The tilt feature on the wheelchair is used to offer increased postural support as well as offering a level of comfort.

Impact

- The wheelchair provision enables the child to be independent.

- It reduces the need for hoisting at school into an alternative static seat, which requires a personal assistant (PA) and multiple transfers to get to different locations.

- This has the potential to reduce the number of PA hours required at circa £35 cost per hour.

- The riser function enables Child A to access different levels without assistance.

- The wheelchair removes the need for additional seating to be purchased, saving money across all 3 funding streams.

- It is calculated that this approach has saved £7,600 per year. The total net benefit over 5 years (the assumed life span of the powered wheelchair) is calculated as £33,150, through savings on static seating and reduce requirement for social care/personal assistance at school for two hours a day.

Challenges

- Child A needed to be able to safely drive the powered wheelchair.

- The home and school environments need to be suitable for the use of the powered wheelchair.

- The family need to have a suitable vehicle or use public transport for all transportation.

- The equipment required for use at home and at school and their respective costs.

Lessons learnt

- The provision of a versatile powered wheelchair eliminates the need for purchasing additional seating and reduces the need for hoisting and assistance at school, potentially leading to a decrease in the number of PA hours required. This saves money for education and social care and also improves the health and wellbeing of the child. This will likely also reduce costs to the health service in the longer run.

Appendix 8: Personalised care and personal health budgets

Children and young people with cerebral palsy may receive a wide range of condition-specific and other NHS-funded services reflecting a spectrum of need. To support joined up care delivery, individuals may be entitled to a personal health budget (PHB). The right to a personal health budget applies to children receiving continuing healthcare.

Personal health budgets can enable the planning and delivery of more personalised and person-centred care for children and young people with cerebral palsy.

Children and young people with cerebral palsy who meet the below criteria will have a legal “right to have” personal health budgets:

- the families of children and young people eligible for continuing care – as defined by the Children and young people’s continuing care national framework – have had a right to have a personal health budget since October 2014. Children and young people and their families who become eligible for continuing care should be informed of their right to have NHS care delivered in this way

- children and young people with cerebral palsy who are referred to and meet the eligibility criteria of their local NHS wheelchair service and people who are already registered with the wheelchair service, will be eligible for a personal wheelchair budget

Children and young people with complex needs, such as cerebral palsy, already receive a wide range of condition specific and generic NHS-funded services. These include: wheelchairs, equipment, orthotics, speech and language therapy, hearing services and continence services.

ICBs should ensure that local eligibility criteria for wheelchairs is based on local need. ICBs should consider the criteria’s impact on all children and young people with cerebral palsy and take into account their social mobility needs to ensure that the local criteria do not prevent children and young people with cerebral palsy from accessing appropriate mobility equipment.

Personal health budgets could improve the integration of these services and people’s experiences.

Appendix 9: Care co-ordinator or key worker

Although cerebral palsy is a “non-progressive” permanent life-long condition, signs and symptoms change with time, with particular challenges at times of growth or in adulthood. The level of support required will therefore change over the life course. With increased need, systems should consider appointing a named care co-ordinator or key worker.

Children and young people and their families with complex needs may be getting health and care support from many different professionals, including nurses, physiotherapist, GPs, surgeons, care workers and managers. Care co-ordinators can help link all this care together.

ICBs, place-based partnerships and provider collaboratives may wish to recruit a care co-ordinator to:

- support a joined-up way of working by facilitating referrals and conversations to ensure timely care and access to specialists, GPs, and community services

- support the initial set up of a multidisciplinary team and champion a proactive approach to a child or young person’s care

- bring together all the information about a person’s care and support needs and play a key role in personalised care and support planning.

- facilitate specific transitions that occur when information about, or accountability for, some aspect of a patient’s care is transferred between 2 or more care entities. The workforce development framework for care co-ordinators sets out professional standards and competencies, outlining guidance on supervision, training, and continuous professional development.

Best practice example: impact of better co-ordination of multidisciplinary team clinics to enable improved care

Case study and ambition

To improve the care of children with cerebral palsy and similar complex needs through specialist clinical practitioners.

What was the issue?

- The clinical care of children with cerebral palsy could be disjointed. Different clinicians, with differing areas of expertise, saw children and families on different dates in varying locations and sometimes provided different advice.

- This was inconvenient and, more seriously, could cause confusion for patients and their carers.

- The communication between the members of the network team of professionals looking after these children was not ideal and led to poorer outcomes.

Solution

- A multidisciplinary clinic was set up, following the CPIP principles and protocols and coordinated by a specialist physiotherapy practitioner. This practitioner expanded her role, completing the non-medical prescribing course, so that she can prescribe and monitor tone-management medications for children coming to clinic.

- The practitioner is undertaking a Masters degree in advancing practice so she can further expand her advanced clinical practitioner role in the future. This may include requesting and interpreting x-rays, applying stretching casts or performing botulinum toxin injections.

Impact

- Children now come to a single clinic and are seen at the same time by a specialist physiotherapist, a paediatrician and an orthopaedic surgeon with occupational therapy as required.

- This has clear benefits to the patient, their carers and the network team addressing the issues mentioned above.

Challenges

- Appropriate support for the multidisciplinary clinics and time and funding is required to enable specialist care practitioners to gain the necessary skills and qualifications for the role.

- Ongoing support is required to cement these roles as fundamental in the care of children with cerebral palsy and similar complex conditions.

Lessons learnt

- A properly funded and supported multidisciplinary team, led by advanced clinical practitioners allows organisations to meet many of the standards required by NICE, the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death and All-Party Parliamentary Group guidance. It is better for patients, carers and clinical staff, improving outcomes as evidenced by similar systems in Scandinavia and Scotland.

- Early intervention for children and young people with cerebral palsy is not only beneficial for the child and their families but can provide longer term value for money as it reduces the need for expensive treatment, such as surgery, in the future.

If you are interested in learning more about any of the case studies featured in this framework, please contact: england.cyptransformation@nhs.net

Publication reference: PRN01517