Summary

The community pharmacy oral anticoagulant safety audit was conducted as part of the 2021/2022 pharmacy quality scheme (PQS). 9,303 pharmacies participated in this audit and submitted data for 131,526 patients over a 7-month period between 1 September 2021 to 31 March 2022.

These medicines were largely used in older patients with nearly 4 in every 5 patients aged 65 or over. This can be explained by the indications of anticoagulants, which are widely used for stroke prevention associated with atrial fibrillation (AF) and the prevention of blood clots following surgeries such as knee and hip replacements – conditions that are more prominent amongst an older population.

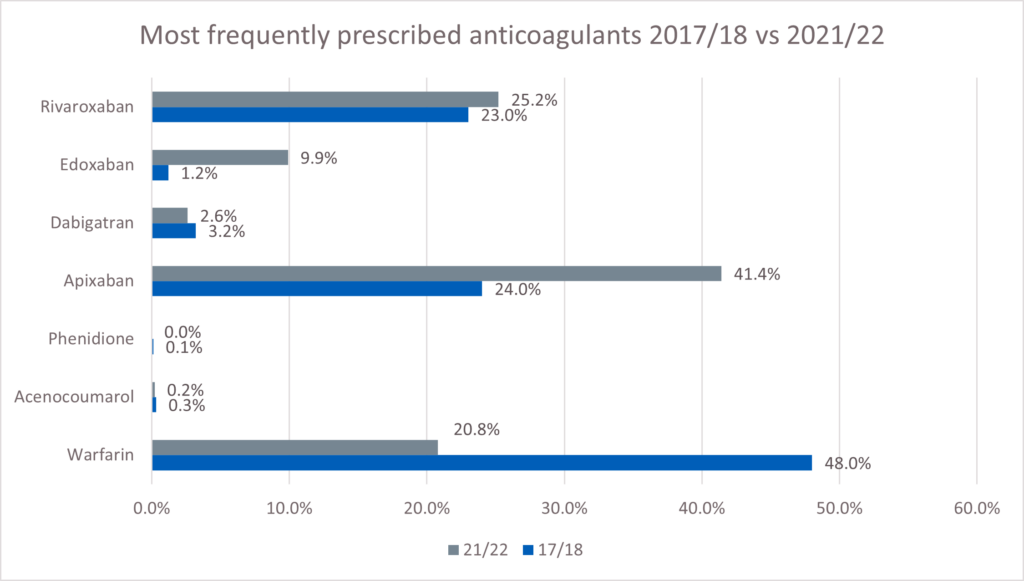

At the time of the audit, the three most frequently prescribed anticoagulants were apixaban (41.4%), rivaroxaban (25.2%) and warfarin (20.8%). This represents a change from the last time community pharmacy teams carried out an audit of anticoagulants in 2017/18 when warfarin accounted for 48% of prescriptions, followed by apixaban (24%) and rivaroxaban (23%).

Key Findings

Anticoagulants, while lifesaving medicines, are also classed as high risk with a potential to cause significant harm. Pharmacy teams can play a significant role in preventing harm by providing patients or carers where appropriate with information and support.

- 4.4% (4,940) of patients were not aware they were prescribed an anticoagulant.

- 23.5% of all patients audited could not describe the symptoms of over-anticoagulation. Pharmacy teams counselled 25,478 (97.4%) of these patients on side effects and signs/symptoms of over anticoagulation.

- 19.8% of patients were unaware of the need to speak to a doctor or pharmacist before taking over the counter (OTC) medicines. 21,033 (95.5%) of these patients were counselled on interactions with OTC medicines including supplements and herbal medicines.

- 21.8% of patients were carrying their yellow anticoagulant card in the pharmacy at the time of consultation. This card is intended to always be carried by all patients taking anticoagulant. Pharmacy teams offered cards to 96.5% of those who reported not owning a yellow anticoagulant card.

- 6,021 patients (4.6%) were prescribed both an anticoagulant and antiplatelet. 748 of these patients (12.4%) were not prescribed any gastrointestinal (GI) protection. Following clinical intervention by the pharmacy team, a further 217 patients (29%) were provided with a prescription for GI protection and 33 patients (4.4%) stopped one or both medicines. Despite clinical intervention, 498 patients remained on both medicines without GI protection.

- 1,201 patients (0.9%) were prescribed both an anticoagulant and a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). 927 (77.2%) of these patients were prescribed GI protection. Following clinical intervention, 151 of these patients (12.6%) had one or both medicines stopped by their GP.

There is still significant scope to improve the safety of patients who require anticoagulation. There has been no improvement in patient knowledge since the audit completed by pharmacy teams in 2017/18, when 15% of patients were unaware of the potential interactions with OTC medicines. Fewer patients were also found to be carrying their yellow anticoagulant cards. Pharmacy teams can play a key role in this via information provision and effective counselling at the point of dispensing, however, there is a wider discussion to be had about the role of the wider multidisciplinary team. This is particularly important for patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), who may be less familiar with their anticoagulant and receive less contact from healthcare professionals due to fewer monitoring requirements.

Recommendations

For community pharmacy

- Proactively discuss the anticoagulant medicine with the patient or representative to ensure safe and effective use, including the signs of over-anticoagulation and the need to check with a doctor or pharmacist prior to starting any OTC medicines.

- Contact the GP practice about:

- all patients prescribed an NSAID and an oral anticoagulant

- all patients prescribed an antiplatelet and an oral anticoagulant without GI protection unless the patient has been referred in the previous 6 months

these patients would be eligible for a Structured Medication Review, which was an indicator in the Investment and Impact Fund 2022/23. This increased collaboration between pharmacy teams and GP practices would improve overall care for patients on anticoagulants.

- Patients who report being overdue international normalisation ratio (INR) blood monitoring should be referred to their GP practice. INR results should be recorded in the patient medication records (PMR) with dates and details of where the result was obtained.

- Educate all patients regarding the importance of carrying yellow anticoagulant cards and offer all patients a card at the point of dispensing.

- Record the information provided to patients, and all referrals in the PMR.

- Ensure there is a supply of yellow anticoagulant cards in the pharmacy, and that the pharmacy team is aware of how to order more when required.

- Ensure all patients have access to information and advice so they can fully understand how to take their anticoagulation medicine, particularly inclusion health groups who have multiple risk factors for poor health and experience poor access to health and care services. Not all patients have equal awareness, understanding and access to primary care and pharmacy teams have an important role in ensuring the individually tailored advice is provided. Pharmacy teams should be mindful of communication preferences for patients with disabilities or when English is not their first language as outlined in the accessible information standard.

For the NHS

- Consider a digital yellow anticoagulant card and booklet for patients to carry via their smart phone to encourage uptake.

- Consider collaboration across primary care to promote the ‘detect, protect and perfect’ methodology for the management of patients on anticoagulants. Acknowledge the responsibility of the whole multidisciplinary team in increasing patient knowledge of these high-risk medicines.

- Focus on further activity to educate patients to optimise benefit and minimise risk from their anticoagulant medicine.

- Further development and testing of data collection tools would increase the utility of the results for the reaudit due to take place in 2023/24.

About this report

This report is intended for:

- Community pharmacists, Primary Care Network (PCN) pharmacists and all healthcare staff responsible for prescribing, dispensing, or reviewing anticoagulant use.

- NHS leaders responsible for patient safety, medicines optimisation and primary care contracts.

- Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) and other national pharmacy bodies.

Purpose

The purpose of this report is to:

- Describe the key findings, learnings and recommendations of the anticoagulant safety audit conducted as part of the 2021/22 community pharmacy quality scheme (PQS).

- Determine if any progress has been made and build on the findings and recommendations of the 2017/18 clinical audit community pharmacies were invited to take part in as one of their two contractually required clinical audits.

- Provide recommendations to support safety improvement for the PQS 2023/24 anticoagulant re-audit.

Background

Anticoagulants are life-saving medicines that can prevent strokes related to atrial fibrillation (AF) and treat venous thromboembolism (VTE). However, this class of medicine is high-risk, with the potential to cause significant harm if they are not taken in accordance with instructions or if prescribed inappropriately.

In 2007, the National Patient Safety Agency issued a patient safety alert that listed 15 high risk factors associated with safety incidents of anticoagulants which at the time comprised of 8-10% of all preventable medication related admissions. In 2020/21, 109 patients were admitted to hospital with a GI bleed and were prescribed an NSAID and an oral anticoagulant. In the same year, 327 were admitted with a GI bleed and were prescribed an oral anticoagulant and an antiplatelet without GI protection.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has launched the third WHO Global Patient Safety Challenge: Medication Without Harm for drugs such as warfarin which have a narrow therapeutic index – its use carries associated risks of bleeding if the INR is too high and risks of further thrombosis if it is too low.

This class of medicine has been highlighted to be a cause of previous preventable and avoidable harm episodes, which have resulted in hospital admissions. As a result, a set of medication safety: prescribing indicators were developed by the NHS Business Services Authority (NHSBSA) as part of a programme of work to reduce associated medication errors. These indicators have been used to build an Anticoagulant Safety Improvement Programme as part of the NHS England Medicines Safety Programme, which aims to reduce the risk of harm for patients prescribed anticoagulants.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS England released a clinical guide for the management of anticoagulant services during the coronavirus pandemic which included guidance on access to face-to-face services and anticoagulant prescribing. The guidance recommended patients prescribed warfarin be switched to DOACs, if appropriate and anticoagulation still indicated to minimise clinic attendance. This is due to a reduction in the monitoring requirements of DOACs when compared to warfarin which requires regular INR monitoring to calculate the dose. The prescribing of DOACs allows patients to receive anticoagulant therapy without the need for frequent blood monitoring which presented an infection control risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, there has been an increase in the prescribing of DOACs.

Supporting both healthcare professionals and patients’ knowledge and use of anticoagulant medicines is therefore even more pertinent to address changes in monitoring, adherence and concomitant medication use.

Further, there have been reported incidents of concurrent prescribing of warfarin and DOACs, which is a patient safety concern. To reduce risk of bleeding, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) advised that healthcare professionals should ensure that warfarin treatment is stopped prior to DOAC initiation. Community pharmacists are well placed to optimise the safe use of anticoagulants and to help ensure a safe transition between therapies as well as promote and encourage patients to return any medication no longer needed.

Anticoagulant audit

This audit was part of the 2021/22 PQS, an incentive scheme for community pharmacy. Data was collected from 1 September 2021 to 31 March 2022. This builds on the voluntary audit, which community pharmacy teams had the opportunity to take part in during 2017/18 designed by the Specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS) that aimed to determine patient awareness of key information about their anticoagulants.

Prior to taking part in the 2021/22 PQS audit, the community pharmacy team was required to have implemented into their day-to-day practice, the findings and recommendations from the Evaluation of patients’ knowledge about oral anticoagulant medicines and use of alert cards by community pharmacists.

Standards were developed for the audit to be able to measure a baseline of performance (see Table 1). To complete the audit, community pharmacy teams were asked to collect data over two weeks with a minimum of 15 patients or four weeks if 15 patients were not achieved within two weeks. In addition, they must have followed up any patient that was referred to their prescriber to identify what actions were taken. The information was reported using the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA) snap survey which was accessed via the Manage Your Service (MYS) application before making the PQS declaration.

Results

9,303 community pharmacies participated and submitted data for 131,526 patients over a 7-month period between 1 September 2021 to 31 March 2022. Most pharmacies were from the Midlands (19.3%), the Northeast and Yorkshire (17.0%) and the Northwest (15.5%). However, there was geographical representation from all regions (see Table 9 in Appendix 1).

131,375 patients were included in the analysis; 151 patients were excluded following data cleansing. Patients aged 70 to 79 years were most frequently prescribed anticoagulants (see Table 10 in Appendix 1). There were more male patients (56.9%) compared to females (43.0%). Table 11 in Appendix 1 provides further details of gender and domiciliary status of patients.

The most commonly prescribed DOACs were apixaban with 54,417 patients (41.4%) and rivaroxaban with 33,118 patients (25.2%) – see Figure 1. Warfarin was the third highest anticoagulant with 27,276 patients (20.8%).

This was expected as the audit took place during 2021/2022 when many patients had been switched from warfarin to DOACs (as per guidance) to reduce the need for face-to-face contact during the COVID-19 pandemic. For patients requiring anticoagulation for the first time, DOACs were the first line treatment option. This shows the change in prescribing practice for anticoagulation compared to the previous 2017/18 audit, which identified warfarin (47.6%) as the most prescribed. Due to this change in prescribing, it is important that pharmacy teams are aware of monitoring requirements and confident to deliver counselling for DOACs.

Figure 1. Prescribed anticoagulant by number of patients

A summary of the findings of the audit against the audit standards are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Audit standards and respective results (reformatted for improved accessibility)

Standard 1: Information and awareness

All patients are aware of or are provided with the following key information:

- the medicine is an anticoagulant, ie a medicine to thin the blood/ prevent blood clots

- the symptoms of over-anticoagulation, eg unexplained bruising, nose bleeds

- to check with a doctor or pharmacist before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements. If taking a vitamin K antagonist (VKA), that dietary change can affect their anticoagulant medicine.

Audit results

- 95.6% of patients prescribed an oral anticoagulant were aware that the medicine is an anticoagulant.

- 80.2% of patients prescribed an oral anticoagulant were aware they need to check with a doctor or pharmacist before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements.

- 67.4% of patients prescribed a VKA were aware that dietary change can affect their anticoagulant medicine.

Recommendation

The audit results highlight a need for increased information and awareness of anticoagulants. Specifically, regarding dietary changes for VKAs, symptoms of over-anticoagulation and checking interactions before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements.

Standard 2: Alert Cards

- All patients have a standard yellow anticoagulant alert card or are offered one.

Audit results

- 66.5% of patients have a standard yellow anticoagulant alert card. 96.5% of those without a card were offered one.

Recommendation

All patients should carry a yellow anticoagulant alert card or a manufacturer alert card. All patients should be offered one by the pharmacist or prescriber.

Standard 3: Safe use with other prescribed medicines – antiplatelets

- Contact the prescriber about all patients prescribed an anticoagulant with an antiplatelet but not co-prescribed GI protection unless referral has been made in the last 6 months or the patient has already discussed with their prescriber.

Audit results

- 4.6% of patients were also prescribed an antiplatelet, of which 12.4% were not co-prescribed GI protection. Contact with the prescriber was made in 57.4% of these cases for review of the patient’s GI protection.

Recommendation

GI protection should be prescribed to patients who are on antiplatelets and anticoagulants, unless contraindicated for the patient.

Standard 4: Safe use with other prescribed medicines – NSAIDs

- The prescriber is contacted about all patients prescribed an anticoagulant with an NSAID.

Audit results

0.9% of patients were concomitantly prescribed an NSAID. 77.2% of these patients were co-prescribed GI protection. 79.5% of patients taking anticoagulants and NSAIDs were referred to the prescriber.

Recommendation

NSAID requirement should be regularly reviewed, and GI protection should be prescribed to patients who are co-prescribed NSAIDs and anticoagulants unless contraindicated for the patient.

Standard 5: INR monitoring and recording

- INR monitoring within the last 12 weeks is confirmed for all patients prescribed VKAs.

Audit results

- 99.3% of patients receiving warfarin had INR monitoring within the last 12 weeks.

Recommendation

All patients who require INR monitoring and have not had a recent test should be referred to the GP practice.

Patient feedback

Table 2 lists the methods of audit data collection used by the pharmacy. The most common method of interaction with patients was through conversation with the patient in the pharmacy (49.5%). The least used method was conversation with the patient by video link (0.02%). Community pharmacists play a vital role in providing high quality face-to-face care and advice; to increase the safe and effective use of anticoagulants. However, patients who are unable to come to the pharmacy due to either being housebound (medicines were delivered to 5.8% of audited patients), representatives collecting medicines (7.9%), or a care home patient (1.7%) do not always receive the same level of care as those visiting the pharmacy because there is no direct interaction between the patient and the community pharmacy team. For these patients, utilising other routes of communication such as telephony, e-mail or video consultation will contribute to improving their care.

Table 2. Methods used for audit collection

| Method of audit collection | Number of patients |

| Conversation with the patient in the pharmacy | 64,991 patients (49.5%) |

| Conversation with the patient by telephone | 45,809 patients (34.9%) |

| Patient’s representative in pharmacy, unable to contact patient | 10,349 patients (7.9%) |

| Medicines delivered by pharmacy, unable to contact patient | 7,597 patients (5.8%) |

| Care home patient, unable to contact patient, representative or care staff | 2,234 patients (1.7%) |

| Contact with patient by other route, eg email | 374 patients (0.3%) |

| Conversation with the patient by video link | 21 patients (0.02%) |

| Total | 131,375 patients (100.0%) |

Concomitant prescribing: multiple oral anticoagulants

231 (0.2%) patients were prescribed multiple anticoagulants. 115 of these patients were switching between anticoagulants and this was the reason for the patient being in possession of two different anticoagulants. In 43 of these cases, the pharmacists provided further advice to the patient to ensure they were not taking the two anticoagulants together and that any unused medication was returned to the pharmacy for safe disposal. After investigation, there were 20 (8.7%) patients who remained on two different anticoagulants with a reason unknown to pharmacy teams. Table 3 provides further information on multiple anticoagulant prescribing.

Community pharmacists are well placed to ensure patients take their anticoagulation medication safely, reminding patients to bring any unused medication back to the pharmacy especially when switching anticoagulants to avoid confusion. Community pharmacists can identify medicines that interact and should refer to the prescriber when appropriate to ensure patient safety.

Table 3. Multiple anticoagulant prescribing

3.1 Patients prescribed more than one anticoagulant

| Patients prescribed more than one anticoagulant | Number of patients |

| Patients on same drug but different strengths | 99 patients (42.9%) |

| Patients prescribed two different anticoagulant drugs | 132 patients (57.1%) |

| Total | 231 patients (100.0%) |

3.2 Actions resulting from pharmacist intervention

| Actions resulting from pharmacist intervention | Number of patients |

| Referral to GP practice | 41 patients (17.7%) |

| Confirmed switching medication | 86 patients (37.2%) |

| Confirmed dose change | 13 patients (5.6%) |

| Confirmed on same drug but different strengths | 77 patients (33.3%) |

| No action/unknown outcome | 10 patients (4.3%) |

| Other | 4 patients (1.7%) |

| Total | 231 patients (100.0%) |

3.3 Actions resulted due to referral to GP practice

| Actions resulted due to referral to GP practice | Number of patients |

| Confirmed switching medication | 29 patients (70.7%) |

| Unknown outcome | 10 patients (24.4%) |

| Confirmed dose change | 1 patient (2.4%) |

| Confirmed on same drug but different strengths | 1 patient (2.4%) |

| Total | 41 patients (100.0%) |

Patient knowledge, awareness, and use of alert cards

111,195 patients completed the patient feedback section of the audit as this section required contact to be made with the patient. Patient feedback highlighted that 95.6% of patients were aware they were taking an anticoagulant. 23.5% of patients were unaware of the symptoms of over-anticoagulation and 19.8% were unaware they needed to check with the doctor or pharmacy before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements (see Table 13 in Appendix 1). This shows that key knowledge is lacking, and counselling and advising patients is essential to improve these outcomes.

66.5% of patients had an anticoagulant alert card, but only 21.8% of patients’ cards were seen by the pharmacy staff. A standard yellow alert card was offered to 96.6% of those patients without a card or those unaware of the card, with 50.7% of these patients accepting the card (see Table 4 for further details). The standard is for 100% of patients to be offered alert cards as they are vital to aid communication with other healthcare professionals and keeping patients safe. All patients should be offered yellow anticoagulant cards at the point of prescribing or dispensing.

Table 4. Yellow anticoagulant cards

4.1 Patient has a standard yellow anticoagulant alert card

| Patient has a standard yellow anticoagulant alert card | Number of patients |

| Yes, card not seen but patient confirmation they have the card | 49,712 patients (44.7%) |

| Yes, card seen by pharmacy staff | 24,189 patients (21.8%) |

| No card or unaware of card | 25,459 patients (22.9%) |

| Not known/Not reported | 11,835 patients (10.6%) |

| Total | 111,195 patients (100.0%) |

4.2 If no card or unaware of card, a standard yellow alert card offered to the patient

| If no card or unaware of card, a standard yellow alert card offered to the patient | Number of patients |

| Yes, card accepted | 12,914 patients (50.7%) |

| Yes, but card declined because the patient has manufacturer’s alert card | 8,877 patients (34.9%) |

| Yes, but card declined because the patient has another anticoagulant alert card | 1,747 patients (6.9%) |

| Yes, but card declined for other reason | 1,038 patients (4.1%) |

| No, not offered | 883 patients (3.5%) |

| Total | 25,459 patients (100.0%) |

Concomitant prescribing: antiplatelets

6,021 (4.6%) patients were co-prescribed an antiplatelet; of these 748 (12.4%) were not prescribed GI protection. 429 (57.4%) of these patients were referred to the prescriber for a review resulting in a further 217 patients receiving a prescription for GI protection and a further 33 patients had medication discontinued – see Table 5. After review, 498 (8.3%) patients, were still concurrently prescribed anticoagulants and antiplatelets without GI protection and were therefore at an increased risk of a GI bleed.

Table 5. Concomitant prescribing – antiplatelets

5.1 Antiplatelet co-prescribed

| Antiplatelet co-prescribed | Number of patients |

| Patients co-prescribed an antiplatelet | 6,021 patients (4.6%) |

5.2 Patient also prescribed gastroprotection

| Patient also prescribed gastroprotection | Number of patients |

| Yes | 5,273 patients (87.6%) |

| No | 748 patients (12.4%) |

| Total | 6,021 patients (100.0%) |

5.3 Prescriber contacted for review of gastroprotection

| Prescriber contacted for review of gastroprotection | Number of patients |

| Yes | 429 patients (57.4%) |

| No | 319 patients (42.6%) |

| Total | 748 patients (100.0%) |

5.4 Prescriber contacted for review of GI protection

| Prescriber contacted for review of GI protection | Number of patients |

| Yes – prescriber discontinued one or both agents | 33 patients (4.4%) |

| Yes – prescriber confirmed no medication changes required | 113 patients (15.1%) |

| Yes – GI protection prescribed | 217 patients (29.0%) |

| Yes – other reason | 66 patients (8.8%) |

| No – prescriber has been contacted about GI protection for this patient within the last 6 months | 89 patients (11.9%) |

| No – patient has discussed with prescriber and has made decision not to take GI protection | 153 patients (20.5%) |

| No – other reason | 77 patients (10.3%) |

| Total | 748 patients (100.0%) |

Concomitant prescribing: NSAIDs

1,201 (0.9%) patients were co-prescribed an NSAID. For 274 (22.8%) of these patients GI protection was not prescribed – see Table 6. Following pharmacist intervention, 151 patients (12.6%) had medication discontinued by their prescriber. The number of patients additionally prescribed GI protection was not calculated due to limitations in the data collected.

Table 6. Concomitant prescribing – NSAIDs

6.1 NSAID co-prescribed

| NSAID co-prescribed | Number of patients |

| Patients co-prescribed an NSAID and anticoagulant | 1,201 patients (0.9%) |

6.2 Prescriber contacted about concomitant use of anticoagulant with NSAID

| Prescriber contacted about concomitant use of anticoagulant with NSAID | Number of patients |

| Yes – prescriber discontinued one or both agents | 151 patients (12.6%) |

| Yes – prescriber confirmed both agents required | 720 patients (60.0%) |

| Yes – other action by prescriber | 84 patients (7.0%) |

| No | 246 patients (20.5%) |

| Total | 1,201 patients (100.0%) |

6.3 Patient also prescribed GI protection

| Patient also prescribed GI protection | Number of patients |

| Yes | 927 patients (77.2%) |

| No | 274 patients (22.8%) |

| Total | 1,201 patients (100.0%) |

Anticoagulant safety issues

6,881 anticoagulant safety issues were flagged (see Table 7 for further details and breakdown by anticoagulant prescribed).

Table 7. Anticoagulant safety issues

| Anticoagulant safety issues | Acenocoumarol | Apixaban | Dabigatran | Edoxaban | Rivaroxaban | Warfarin | Total actions taken |

| Interactions discussed/checked | 4 acenocoumarol patients | 769 apixaban patients | 33 dabigatran patients | 194 edoxaban patients | 465 rivaroxaban patients | 326 warfarin patients | 1,791 total patients |

| Diet advice | 0 acenocoumarol patients | 83 apixaban patients | 2 dabigatran patients | 11 edoxaban patients | 73 rivaroxaban patients | 379 warfarin patients | 548 total patients |

| Symptoms/side effects discussed | 4 acenocoumarol patients | 836 apixaban patients | 52 dabigatran patients | 220 edoxaban patients | 532 rivaroxaban patients | 255 warfarin patients | 1,899 total patients |

| OTC medicines | 3 acenocoumarol patients | 674 apixaban patients | 45 dabigatran patients | 166 edoxaban patients | 418 rivaroxaban patients | 262 warfarin patients | 1,568 total patients |

| Advice about bleeds/bruising | 4 acenocoumarol patients | 381 apixaban patients | 20 dabigatran patients | 109 edoxaban patients | 267 rivaroxaban patients | 110 warfarin patients | 891 total patients |

Ongoing bleeds/bruising | 0 acenocoumarol patients | 71 apixaban patients | 5 dabigatran patients | 31 edoxaban patients | 63 rivaroxaban patients | 14 warfarin patients | 184 total patients |

| Total | 15 acenocoumarol patients | 2,814 apixaban patients | 157 dabigatran patients | 731 edoxaban patients | 1,818 rivaroxaban patients | 1,346 warfarin patients | 6,881 total patients |

Note: there were no anticoagulant safety issues flagged by patients prescribed phenindione.

Multi-compartment Compliance Aid (MCA)

11.3% of patients taking anticoagulants had their medicines dispensed in an MCA. Good compliance was observed for the exclusion of warfarin from MCAs (98%). DOACs, notably apixaban with 8,344 patients (15.3%), edoxaban with 1,666 patients (12.8%) and rivaroxaban with 4,029 patients (12.2%) were dispensed in an MCA. Minimal dose changes are needed for DOACs unlike warfarin where the dose is dependent on the INR and can vary from day-to-day.

However, 246 patients on dabigatran (7.3%) were also dispensed in an MCA. This is contrary to manufacturers recommendations, which state this medication should be stored in original packaging due to stability issues. This is a potential safety concern. See Table 12 in Appendix 1 for further breakdown of MCA dispensing for each anticoagulant.

Vitamin K antagonists

99.3% of patients prescribed warfarin who responded (68.1%) had an INR test carried out within the last 12 weeks, in line with current NICE guidelines, which recommends that once patients are stable they have their INR monitored up to every 12 weeks – see Table 8.

67.4% (16,764) of warfarin patients were aware that dietary change can affect their anticoagulant medicine. It should be standard practice for all patients prescribed medicines that have a dietary interaction to have a conversation with the prescriber or pharmacist, to ensure that the patient understands the potential impact and how to manage/avoid foods that may cause an interaction.

Table 8. Vitamin K antagonists only

8.1 Key knowledge

| Patients already aware that dietary change can affect their anticoagulant medicine | Number of patients |

| Yes | 16,764 patients (67.4%) |

| No – information not provided | 353 patients (1.4%) |

| No – information provided | 3,868 patients (15.5%) |

| Not applicable | 3,898 patients (15.7%) |

| Total | 24,883 patients (100.0%) |

8.2 INR testing

| For warfarin, INR test carried out: (N=27,276) | Number of patients |

| 4 to 12 weeks | 5,978 patients (32.2%) |

| Less than 4 weeks | 12,468 patients (67.1%) |

| More than 12 weeks | 138 patients (0.7%) |

| Total | 18,584 patients (100.0%) |

8.3 Actions taken

| For patients, whose INR tests were more than 12 weeks ago, actions taken: (N=138) | Number of patients |

| Six monthly tests | 2 patients |

| Advice given | 1 patient |

| Advised patient to book test | 42 patients |

| Contacted GP | 8 patients |

| Contacted patient representation | 2 patients |

| No action taken | 9 patients |

| Patient to Contact GP | 1 patient |

| Referred to GP | 15 patients |

| Patient self-checks | 3 patients |

| Stable patient | 12 patients |

| Test booked | 42 patients |

| Updated patient record | 1 patient |

| Total | 138 patients |

Discussion

Pharmacy teams provided advice and made significant clinical intervention preventing potential harm for patients at increased risk of harm 33,173 times throughout the course of this audit, showing they have a real role to play in educating and managing patients who are prescribed these high-risk medicines. Pharmacists play an important role in identifying potential interactions, discussing symptoms, and advising patients of side effects. This audit indicates that safety requirements for the use of anticoagulants are still not being fully met and there is scope for the contribution of pharmacy teams to be further enhanced.

Reassuringly a very small minority of patients were unaware they were prescribed an anticoagulant, however almost 1 in 4 patients could not describe the signs or symptoms of over anticoagulation and 1 in 5 patients were not aware of the need to consult a doctor or pharmacist prior to starting any non-prescribed medicines.

Only 1 in 5 patients were found to be carrying their yellow anticoagulant card at the time of consultation in the pharmacy. Consideration should be given in a digital age, of how a yellow anticoagulant card in a digital form might increase patient engagement, whilst also contributing to the NHS “Net Zero” initiative.

It is vital that both patients and prescribers are aware of the risks associated with co-prescribing anticoagulants with other medicines that increase the risk of GI bleeding such as NSAIDs and antiplatelets. Community pharmacy teams should continue to flag these interactions to prescribers and recommend GI protection. NSAID use in patients on anticoagulants should be regularly reviewed so it can be discontinued as soon as it is no longer required.

As patient knowledge has not been shown to increase since a similar audit was carried out by community pharmacy teams in 2017/18, there is significant scope for the wider local MDT to work together to reduce risk, embed the recommendations made in this report and further decrease the rates of preventable hospital admission associated with anticoagulants.

Further recommendations for community pharmacy teams and the NHS can be found in the Summary of this report. All pharmacies should adhere to these recommendations and document all information provided and referrals in the PMR.

Community pharmacy teams will be asked to look at how they can work with local multidisciplinary teams to improve anticoagulant safety and implement the recommendations of this report and a reaudit will be conducted to monitor progress as part of the 2023/24 PQS.

Appendix 1: Anticoagulant audit data summary tables

Appendix 1 descriptive statistics: measures of dispersion, variance, or frequency

Table 9. Geographical distribution of responses and no. of patients audited in the region

| Region | Number of Pharmacies | Number of Patients |

| East of England | 970 pharmacies (10.4%) | 13,715 patients (10.4%) |

| London | 1,368 pharmacies (14.7%) | 18,683 patients (14.2%) |

| Midlands | 1,799 pharmacies (19.3%) | 25,735 patients (19.6%) |

| North East and Yorkshire | 1,583 pharmacies (17.0%) | 22,461 patients (17.1%) |

| North West | 1,444 pharmacies (15.5%) | 20,700 patients (15.7%) |

| South East | 1,265 pharmacies (13.6%) | 17,785 patients (13.5%) |

| South West | 874 pharmacies (9.4%) | 12,447 patients (9.46%) |

| Total | 9,303 pharmacies (100.0%) | 131,526 patients (100.0%) |

Table 10. Anticoagulant prescribing breakdown by gender and age

| Age Band | Male | Female | Gender not specified | Total |

| 18-29 | 385 | 353 | 1 | 739 (0.6%) |

| 30-39 | 977 | 1,129 | 2 | 2,108 (1.6%) |

| 40-49 | 2,181 | 2,937 | 6 | 5,124 (3.9%) |

| 50-59 | 4,524 | 7,848 | 13 | 12,385 (9.4%) |

| 60-69 | 8,885 | 15,592 | 30 | 24,507 (18.7%) |

| 70-79 | 17,440 | 25,778 | 16 | 43,234 (32.9%) |

| 80-89 | 17,441 | 18,116 | 13 | 35,620 (27.1%) |

| 90-108 | 4,601 | 3,055 | 2 | 7,658 (5.8%) |

| Total | 56,434 | 74,858 | 83 | 131,375 (100.0%) |

Table 11. Breakdown of patient demographics

11.1 Gender

| Gender | Number of patients |

| Male | 56,434 patients (43.0%) |

| Female | 74,858 patients (56.9%) |

| Gender status unknown | 83 patients (0.1%) |

| Total | 131,375 patients (100.0%) |

11.2 Residential status

| Residential status | Number of patients |

| Care home resident | 3,734 patients (2.8%) |

| Not care home resident | 126,172 patients (96.0%) |

| Residential status unknown | 1,469 patients (1.1%) |

| Total | 131,375 patients (100.0%) |

Table 12. Breakdown of MCA dispensing for each anticoagulant

| MCA dispensing | Acenocoumarol | Apixaban | Dabigatran | Edoxaban | Phenindione | Rivaroxaban | Warfarin | Total |

| No | 189 acenocoumarol patients (95.0%) | 46,073 apixaban patients (84.7%) | 3,123 dabigatran patients (92.7%) | 11,313 edoxaban patients (87.2%) | 16 phenindione patients (94.1%) | 29,089 rivaroxaban patients (87.8%) | 26,728 warfarin patients (98.0%) | 116,531 total patients (88.7%) |

| Yes, multiple medicines per blister/compartment | 6 acenocoumarol patients (3.0%) | 7,074 apixaban patients (13.0%) | 185 dabigatran patients (5.5%) | 1,380 edoxaban patients (10.6%) | 0 phenindione patients (0%) | 3,308 rivaroxaban patients (10.0%) | 368 warfarin patients (1.3%) | 12,321 total patients (9.4%) |

| Yes, one medicine per blister/ compartment | 4 acenocoumarol patients (2.0%) | 1,270 apixaban patients (2.3%) | 61 dabigatran patients (1.8%) | 286 edoxaban patients (2.2%) | 1 phenindione patient (5.9%) | 721 rivaroxaban patients (2.2%) | 180 warfarin patients (0.7%) | 2,523 total patients (1.9%) |

| Total | 199 acenocoumarol patients (100.0%) | 54,417 apixaban patients (100.0) | 3,369 dabigatran patients (100.0%) | 12,979 edoxaban patients (100.0%) | 17 phenindione patients (100.0%) | 33,118 rivaroxaban patients (100.0%) | 27,276 warfarin patients (100.0%) | 131,375 total patients (100.0%) |

Table 13. Key knowledge understanding

13.1 Patients already aware that they are taking an anticoagulant

| Patients already aware that they are taking an anticoagulant, ie a medicine to thin the blood/prevent blood clots | Number of patients |

| Yes | 106,255 patients (95.6%) |

| No – information provided | 4,607 patients (4.1%) |

| No – information not provided | 333 patients (0.3%) |

13.2 Patients who already know the symptoms of over-anticoagulation

| Patients who already know the symptoms of over-anticoagulation, eg unexplained bruising, nose bleeds | Number of patients |

| Yes | 85,029 patients (76.5%) |

| No – information provided | 25,478 patients (22.9%) |

| No – information not provided | 688 patients (0.6%) |

13.3 Patients already aware of the need to check with the doctor or pharmacist before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements

| Patients already aware of the need to check with the doctor or pharmacist before taking OTC medicines, herbal products, or supplements | Number of patients |

| Yes | 89,171 patients (80.2%) |

| No – information provided | 21,033 patients (18.9%) |

| No – information not provided | 991 patients (0.9%) |

| Total | 111,195 patients (100.0%) |

Table 14. Breakdown of patients with or without a yellow anticoagulant card by anticoagulant

| Yellow Anticoagulant Card | Acenocoumarol | Apixaban | Dabigatran | Edoxaban | Phenindione | Rivaroxaban | Warfarin | Total |

| No card, or unaware of card | 30 acenocoumarol patients | 10,930 apixaban patients | 660 dabigatran patients | 2,659 edoxaban patients | 3 phenindione patients | 7,619 rivaroxaban patients | 3,558 warfarin patients | 25,459 total patients |

| Not known/Not reported | 15 acenocoumarol patients | 5,338 apixaban patients | 350 dabigatran patients | 1,282 edoxaban patients | 4 phenindione patients | 3,483 rivaroxaban patients | 1,363 warfarin patients | 11,835 total patients |

| Yes, card not seen but patient confirmed they have this card | 85 acenocoumarol patients | 19,746 apixaban patients | 1,274 dabigatran patients | 4,807 edoxaban patients | 5 phenindione patients | 11,822 rivaroxaban patients | 11,973 warfarin patients | 49,712 total patients |

| Yes, card seen by pharmacy staff | 43 acenocoumarol patients | 8,850 apixaban patients | 548 dabigatran patients | 2,080 edoxaban patients | 4 phenindione patients | 5,202 rivaroxaban patients | 7,462 warfarin patients | 24,189 total patients |

Total | 173 acenocoumarol patients | 44,864 apixaban patients | 2,832 dabigatran patients | 10,828 edoxaban patients | 16 phenindione patients | 28,126 rivaroxaban patients | 24,356 warfarin patients | 111,195 total patients |

Appendix 2: Anticoagulant audit data collection tool

Anticoagulant audit data collection tool used by contractors as part of 2021/22 PQS. For information only.