Purpose

This guide helps organisations adopt a personalised, least-restrictive therapeutic approach of enhanced therapeutic observation and care (ETOC).

It informs every stage of assessment and decision-making to ensure its use is minimised through proactive step down, meaning a deliberate and timely reduction of intervention when risks safely allow.

Context

In September 2024, NHS England launched a multi-year ETOC improvement programme to help organisations make local, clinically led, patient-centred improvements to their ETOC provision.

For further information about resources and the improvement programme, please visit the ETOC website.

Additional resources can be accessed by joining the ETOC Programme page (FutureNHS login required).

Moving from risk management to a therapeutic approach

There is a growing trend towards using enhanced observation for patients whose needs extend beyond standard care provisions.

Despite efforts from organisations to improve practice, clinical leaders and patients highlight the need for a crucial change, moving beyond reactive risk mitigation to purposeful engagement through person-centred, therapeutic interventions.

As stated by an inpatient mental health service user, West London NHS Trust:

“You cannot make me safe; you can only care for me in the way that I need, and then I will feel safe.”

This patient reflection reminds us that safety stems from tailored care, and consequently, a patient-centred therapeutic approach becomes paramount.

This shift directly supports the reduction in health inequalities, helps eliminate restrictive or custodial care and deconditioning, and fundamentally strengthens individual autonomy.

Therapeutic enhanced observation can be defined as:

Providing safe, effective, and person-centred care to patients who require additional support; and delivering this in a way which moves away from passively observing and watching patients, to actively supporting and engaging with them in a meaningful way to aid rehabilitation, recovery, improve outcomes and experiences.

The National Mental Health and Learning Disability Nurse Directors Forum have developed Enhanced Care Guiding Principles which outlines a therapeutic and person-centred approach.

Considering the adverse impact enhanced observations may have on the patient if applied incorrectly, there must be an individual justification and proportionate reasoning for its use, and staff should apply a least restrictive therapeutic approach.

This includes stepping down enhanced observation right from the start, which reduces excessive or prolonged ETOC usage, improves care and conserves resources for wider health and care needs.

What does a therapeutic approach mean in practice?

A therapeutic approach is being person-centred and recognising patients as partners in the management of their own safety and care.

It incorporates actively involving and engaging patients and their support networks in shared decision-making, using appropriate language and communication, fostering professional self-awareness and reflection, and embedding trauma-informed care in practice.

The idea of being person-centred has been helpfully articulated by staff at Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust as:

“Truly understanding a patient and ensuring their safety goes beyond understanding visible and non-visible symptoms. If we invest in the patient and their story, we can elevate care from treatment to recovery.”

These principles form the foundation of a therapeutic culture and should be at the heart of every patient interaction. They are defined in more detail in appendix 1.

Embedding step down into the pathway

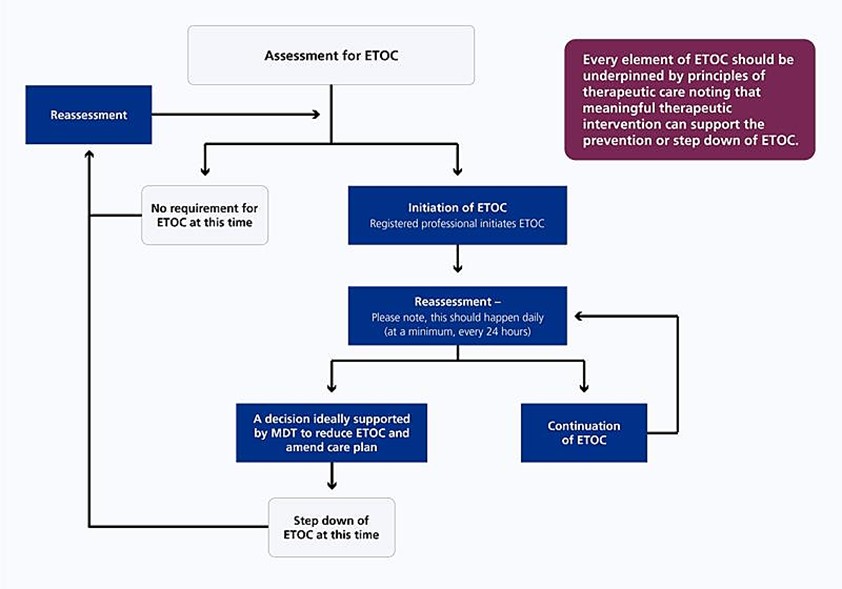

Frequent reviews should be embedded into ETOC care pathways and outlined in the trust’s ETOC policy to consider whether step down is appropriate, as shown in the example below. Further information is available in the ETOC policy guide.

Every element of ETOC should be underpinned by principles of therapeutic care, noting that meaningful therapeutic intervention can support the prevention or step down of ETOC, improve outcomes and experiences.

Figure 1: Example ETOC pathway

Notes on figure 1

The process begins with Assessment for ETOC. From here, there are 2 possible routes:

- If there is no requirement for ETOC currently, the pathway ends. However, the path returns to reassessment if future care needs determine that this is required.

- If ETOC is needed, the next step is initiation of ETOC. This is followed by reassessment – please note, this should happen daily, and frequency should be dependent on the patient’s individual needs and associated risks (at a minimum, once every 24 hours). From this point, there are 2 options:

- a decision ideally supported by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) to reduce ETOC and amend care plan, which leads to discontinuation of ETOC then returns to reassessment if future care needs determine this is required

- continuation of ETOC, which loops back into the daily reassessment

The following case studies illustrate the process organisations may take to embed a step down and thorough gatekeeping process to manage the appropriate, human rights-based and least restrictive use of ETOC.

Local example – Minimising the use of ETOC through effective leadership and governance

Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust approvals process observes the following steps:

- An assessment is completed at ward level.

- A matron undertakes a review.

- This is submitted for review to the group director of nursing or nominated deputy, who approves or declines this request.

- The vulnerable person’s team perform a retrospective review.

Each referral must have:

- an executive sign off with the group director of nursing and matron for oversight

- personalised care planning with patient and carer involvement, including a review of autistic people or individuals with a learning disability

- a review of patients with deprivation of liberty applications by the safeguarding team

- clinical leadership support for those at point of care to deliver the least restrictive and proportionate practice

- core data captured for additional staffing requests

- reasonable adjustments explored

- risk assessment tool completed, with guidance and prompts that identifies if continuous observation is required

- staffing requests completed for executive sign off, and daily reassessment and update of the requirement

The thorough assurance process for ETOC referrals results in a transparent, accountable and open leadership which fosters a culture of psychological safety.

Staff, patients and families can speak up and raise any concerns at any point during the referral process.

Local example – Reducing and discontinuing enhanced observations

Royal Devon NHS Foundation Trust has a clear process for reducing and discontinuing ETOC for patients who no longer require the intervention. Their decision-making is solution-focused and patient-centred.

The process is clearly outlined for staff to follow and includes a review at care group to determine suitability for step down. Twice weekly, the care group meets with clinical matrons to review all patients on ETOC, providing staff support and considering risk profile and complexity.

Key considerations when reducing enhanced observation include:

- expressions of distress or need

- medical history

- specialist input

- care plan review

- impact of interventions

- risk

- unmet need

- environment

Staff have fed back that they feel supported in ETOC decision-making, with review meetings providing assurance that any interventions are supportive. They have also helped staff apply pragmatic and proportionate decisions based on evidence.

Supportive enquiry

Supportive enquiry explores the presenting health problem from the patient’s perspective, then introduces therapeutic interventions to address the specific identified health concerns.

It encourages staff to understand what may be triggering the presenting health concern and promotes more compassionate and effective care.

Local example – Considering ETOC in the round

At South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, staff are encouraged to consider and address the following factors when considering ETOC:

- biological: pain, medication

- social: boredom, deviation from routine, seeking social interaction

- psychological: lack of knowledge of what is happening, loss of control, feeling labelled or excluded, known mental health conditions

- environmental: noise, lighting

- staff approach: communication style, previous experience and knowledge of the patient

Local example – Taking a therapeutic approach to managing patients with complex needs

At the emergency department in Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead, a young person with complex learning and mental health needs presented in crisis.

In addition to completing a Mental Health Act assessment, the patient received care guided by a positive behaviour support plan co-developed with their community team.

The support plan detailed known triggers, calming strategies, preferred language, and effective de-escalation techniques, which enabled staff to personalise care and modify the environment to reduce distress.

The patient also brought an emotional regulation ‘grab bag’ containing self-soothing tools, which staff used proactively to maintain calm and build a therapeutic connection.

A strong multidisciplinary team with representatives across community and acute services met regularly, shared updates, and collaborated on real-time adjustments to care.

Compassionate care was enabled through staff reflection, trauma-informed approaches, and patient-led planning. The young person and their family were actively involved in discharge decisions, choosing the timing, setting and support preferences.

Since then, the trust has introduced adapted cubicles with low stimulation features to support patients who identify as neurodiverse or are experiencing mental health crises.

Staff continue to draw upon strong working relationships between acute and community to personalise support.

Therapeutic interventions

Staff at NHS University Hospitals of Liverpool Group defined therapeutic interventions as:

“Offering bespoke support focusing on the patient as a human being so their time in hospital is safer and more comfortable. We need to know who the person is, offering support tailored to this, and we must remember that through all of our practice and their hospital journey.”

Therapeutic interventions are a key component of ETOC and may include:

- emotional and psychological support interventions – such as active listening, validation, de-escalation techniques, guided self-reflection, grounding exercises, and trauma-informed approaches to help patients manage distress, process experiences and build resilience.

- relational and communication-based interventions – including building therapeutic rapport, restorative conversations and supporting social connection

- practical and sensory-based interventions – such as offering comfort items, sensory tools, or engaging in calming activities like drawing, music or walks

- clinical and care planning interventions – such as active physical rehabilitation, medication reviews, involving patients in care planning or problem-solving conversations to promote autonomy and shared decision-making

Trusts should start to develop models that move away from enhanced observation as an intervention and instead embed therapeutic interventions into everyday practice and step-down the use of enhanced observations where appropriate.

The following case studies illustrate the process organisations have taken to do this.

Local example – Introducing roles to assist with the promotion of patient activities

University Hospitals of North Midlands recognised the fundamental importance of therapeutic engagement and activity. They introduced a non-registered role to cover all the older adult inpatient wards to boost patient engagement, activity and mobility.

They ran tailored activities (such as games, puzzles and chair exercises), used distraction techniques for therapeutic monitoring, and worked with families to restore patient routines.

A competency framework defined their role and standards, guiding training and development.

Evidence packs helped document activities and feedback, supporting consistent practice and evaluation across wards.

During this time, falls dropped by 20%, and violence and aggression incidents fell by 58% within 6 months. 6 of the 7 wards made the roles permanent.

The trust is now trialling 7-day coverage and expanding the role to other units.

Local example – A quality improvement approach to reduce patient distress

The Cavendish Group ran a quality improvement programme to improve the therapeutic quality of enhanced observation in 10 mental health wards across London.

Several changes were introduced, including incorporating unstructured activity into routine shifts, amending observation review structures, more frequent safety huddles, de-escalation training for staff, and the introduction of personal safety plans.

The enhanced care model, based on the Healthcare Improvement Scotland Framework and NHS England’s Culture of care standards for mental health inpatient services, were pivotal in shaping the approach.

All wards saw a decrease in enhanced observation days, ranging between 33% and 75%.

This was often coupled with significant reduction in other areas of restrictive practice, such as seclusion, enforced treatment and restraint; 1 ward saw a 97% reduction on average in seclusion days.

3 wards also saw up to 50% reductions in patient violence and aggression incidences toward staff.

Stakeholders agreed that the shift from passive observation to active engagement and evidence-based interventions led to a significant improvement in patient safety and care quality.

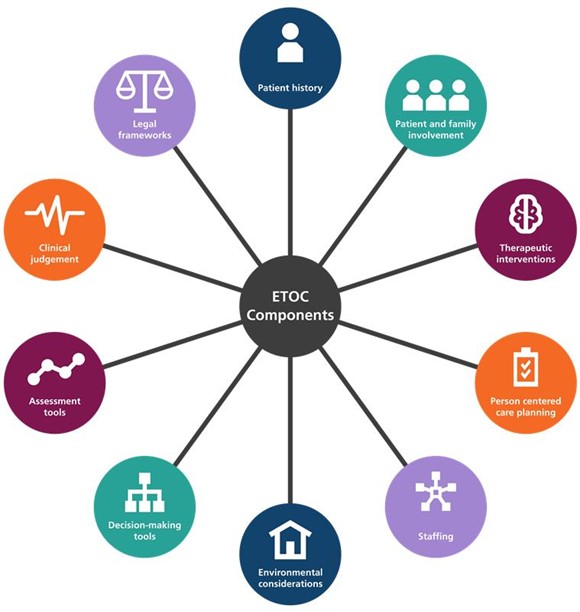

10 components of enhanced therapeutic observation and care assessment

Based on learning from trusts that have significantly improved their ETOC assessment, 10 core components have been identified to support the delivery of therapeutic care that focuses on holistic assessment, planning and delivery.

Figure 2: 10 ETOC components

Note on figure 2

The 10 ETOC components here are (clockwise from top):

- Patient history

- Patient and family involvement

- Therapeutic interventions

- Person-centred care planning

- Staffing

- Environmental considerations

- Decision-makings tools

- Assessment tools

- Clinical judgement

- Legal frameworks

Environmental considerations

The physical setting should support safety, recovery and reduce distress. Staff should:

- assess and adjust the environment to individual needs (such as sensory spaces for neurodiverse patients)

- adjust the environment to potential risk (for example, managing potential ligature points and self-harm risks)

- develop and review environmental risk plans (including suitability) regularly

Patient history

A comprehensive understanding of a patient’s background is essential for tailoring care. This includes:

- reviewing clinical records, past behaviours, diagnoses and responses to previous observations

- consulting with the patient, family or carers, and external services

- identifying behavioural patterns and looking at possible interventions

- treating medical causes, if appropriate, before initiating ETOC

Patient and family involvement

Involving families and support networks enhances person-centred care and strengthens trust. This includes:

- encouraging support networks to share their understanding of triggers, warning signs and preferences and to support enhanced observations where appropriate

- considering cultural, spiritual and communication needs

- informing and involving support networks in care planning and risk assessments, seeking feedback on wellbeing and support needs

Therapeutic interventions

- Consider therapeutic interventions section above.

- These interventions should be continuously evaluated and reviewed.

Care planning

Dynamic, accessible and person-centred care planning is crucial. This involves:

- documenting the ETOC plan, including therapeutic strategies, privacy, crisis protocols, medication and review cycles (minimum every 24 hours)

- keeping care plans live, regularly updated and shared across teams and settings to ensure continuity

- embedding insights into care plans and risk assessments for consistent multidisciplinary communication

- MDT decision-making should be encouraged when multiple providers are involved in a patient’s care, with the accountable provider retaining final responsibility for the care plan

Legal frameworks

Staff must understand and operate within relevant legal frameworks. This includes:

- familiarity with the Human Rights Act, Mental Health Act, Mental Capacity Act, Deprivation of Liberty Standards, Children Acts, and the Use of Force Act

- training in safeguarding and understand how legislation impacts on ETOC decisions

Assessment tools

Assessment tools should inform clinical understanding and care. This involves:

- including tools to assess behaviour, physical needs and environmental factors

- ensuring staff are trained in their use, and that tools are integrated with digital systems where possible

Decision-making tools

Structured tools help ensure consistency and transparency in assessments. This involves:

- using risk matrices to assess domains like communication, behaviours and anxieties, personal safety, swallowing, hydration and nutrition to create a comprehensive risk profile

- designing evidence-based tools using quality improvement (QI) methodologies and to support decision-making alongside clinical judgement

- it is important for any locally designed tools to have strong evidence base as without it the validity may be difficult to determine

Clinical judgement

Professional expertise remains central to determining appropriate, proportionate, person-centred ETOC. This includes:

- supporting staff to build confidence and competence in decision-making.

- providing supervision, mentorship and multidisciplinary team collaboration to guide initiation and review of ETOC provision

Staffing

Well-supported, trained staff are fundamental to delivering safe ETOC. This includes:

- ensuring roles and responsibilities of staff are clearly outlined in the trusts ETOC policy. Further information is available in the ETOC policy guide.

- allocating staff based on patient needs and risk profiles

- providing appropriate breaks, debriefs and supervision

- having clear procedures in place regarding workforce planning and workforce deployment, including escalating staffing needs and adjusting deployment based on the needs of patients

Local example – A quality improvement approach to improving an ETOC decision making tool

In 2023, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (LTHT) identified the need to improve decision-making around enhanced care by redesigning their risk assessment tool following staff feedback.

After conducting audits of the current tool, a multidisciplinary team developed a new enhanced care risk assessment tool using the Leeds Improvement Method.

The new tool supports clear clinical judgment, including a 3-day review cycle with an embedded process for supporting the decision making around increasing and decreasing the level of care recognising patient’s holistic needs.

It focuses on patient behaviours and the required interventions rather than staff location.

It was co-designed with stakeholders and supported by improved terminology, guidance and alignment across wards.

The tool was embedded through staff training, audits and ward-level champions.

Results showed increased staff confidence and clarity. 96% of nurses felt supported by the tool, and 98% valued the patient and carer voice in assessments.

Use of security staff dropped significantly, with a cost saving of over £100,000 a year, while maintaining safe, high-quality care.

LTHT is continuing development through an internal stakeholder group, digital integration and national collaboration.

Appendix 1 – An example of therapeutic ETOC principles

Nurse leaders developed 5 guiding principles to shape how staff approach every stage of ETOC provision:

Person-centred approach

Staff should recognise the individual’s values, routines, culture and context, promoting dignity and trust through tailored, empathetic care.

Shared decision-making

Staff should seek to actively involve patients in care decisions wherever possible to uphold autonomy.

Advocates, relevant legal frameworks, capacity re-assessments and best interest processes should be used when capacity is limited.

Effective language and communication

Staff should be mindful of how we talk about and speak to our patients.

They should employ plain language, active listening, and calm body language to build rapport and reduce distress, adjusting their approach based on the patient’s needs.

Gathering information on early warning signs, potential triggers, and how the patient typically responds to different forms of communication can help guide a more sensitive and effective approach.

Self-awareness and reflection

Regular reflection supports professional boundaries, emotional resilience and quality of care.

Staff should recognise how their own beliefs, emotions and behaviours influence their interactions with patients, especially in the emotionally demanding context of ETOC.

Staff should be considerate about the language they use to describe patients.

Using compassionate, non-judgemental terms contributes to a therapeutic environment where patients feel understood rather than labelled.

Trauma-informed practice

Many patients have trauma histories, so care should be delivered with sensitivity to triggers, emotional needs and support patient autonomy.

Publication reference: PRN01862_iii