Introduction

In 2022, the Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Inpatient Quality Transformation Programme was established to support cultural change and a new bold, reimagined model of care for the future across all NHS-funded mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient settings.

The culture of care standards for mental health inpatient care set out in this guidance support all providers to realise the culture of care within inpatient settings everyone wants to experience – people who need this care and their families, and the staff who provide this care. They apply across the life course to all NHS-funded mental health inpatient service types, including those for people with a learning disability and autistic people, as well as specialised mental health inpatient services such as mother and baby units, secure services, and children and young people’s mental health inpatient services.

The standards represent the collective vision we all hold for our inpatient services. They were co-produced with people with lived experience of inpatient services and their families; nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, allied health professionals and other staff who work in inpatient settings at various levels of the organisation; voluntary sector organisations; royal colleges; and academic experts. Further consultation was undertaken with key stakeholders across the system, at national, regional, system and provider level, and with additional focus groups of people with lived experience, particularly those with experience of secure inpatient settings and people from Black and minority ethnic communities.

We acknowledge that the standards are ambitious, particularly in the context of current workforce pressures. However, we know that achieving a positive workplace culture is critical to improved patient outcomes [1]. It tackles barriers we know get in the way of staff providing the care they want to give to patients by boosting employee engagement and performance [2] and staff retention [3]. The culture of care articulated in this guidance will support patients and their families to flourish, and staff to flourish; to be proud to work in inpatient care and supported to deliver the care they came into their profession to give.

The standards reflect the potential for change across all service types, and convey the core belief that each person has the power to make a difference. Collectively, and with the right implementation support, that power can mobilise whole organisations and communities.

Note on language

This guidance has been written with everyone who may use mental health hospitals in mind, and the language we use reflects this inclusive approach.

We have avoided buzzwords, recognising that some ideas and frameworks that are intended to initiate positive change have instead been co-opted or assimilated into mainstream culture and practice in ways that can be painful for patients and families to experience. We have precisely described the improvements needed to create meaningful changes in inpatient services.

We do refer to ‘patient’ where we want to clearly differentiate those receiving care from staff or people more generally and make explicit the power differentials within inpatient settings. We considered patient to be the least objectionable term, supported by literature [4] and general consensus within our design group, including people with lived experience. Where we refer to ‘people’ we intend to be inclusive of patients, staff and visitors.

We have tried to select language that respects the multiple understandings of mental distress, crisis and illness, and the range of needs and experiences that might bring people to hospital. While the guidance avoids traditional terms like ‘serious mental illness’, it has been co-produced with, and is relevant to, the range of people who may need hospital care, including those who identify or are sometimes described as having such illness.

Our vision for inpatient care

Our co-produced vision for inpatient care

The purpose of inpatient care is for people to be consistently able to access a choice of therapeutic support, and to be and feel safe. Inpatient care must be trauma informed, autism informed and culturally competent.

Being in hospital is a form of restriction in and of itself, and it is our moral and legislative duty to provide the least restrictive experience possible within inpatient settings with a clear focus on balancing the right to liberty with therapeutic benefit.

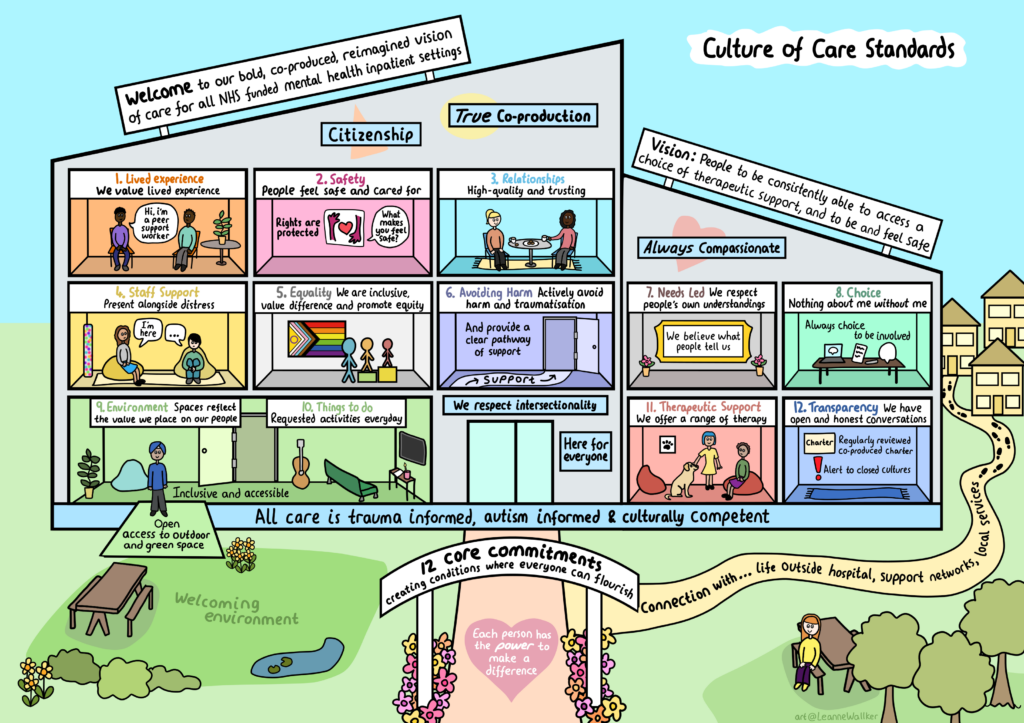

To support this vision we have co-developed 12 overarching core commitments, each of which has a set of associated standards. Work to improve the culture of care on inpatient wards – creating the conditions where patients and staff can flourish – should focus on these core commitments.

- lived experience: We value lived experience, including in paid roles, at all levels – design, delivery, governance and oversight

- safety: People on our wards feel safe and cared for

- relationships: High-quality, rights-based care starts with trusting relationships and the understanding that connecting with people is how we help everyone feel safe

- staff support: We support all staff so that they can be present alongside people in their distress.

- equality: We are inclusive and value difference; we take action to promote equity in access, treatment and outcomes

- avoiding harm: We actively seek to avoid harm and traumatisation, and acknowledge harm when it occurs

- needs led: We respect people’s own understanding of their distress

- choice: Nothing about me without me – we support the fundamental right for patients and (as appropriate) their support network to be engaged in all aspects of their care

- environment: Our inpatient spaces reflect the value we place on our people

- things to do on the ward: We have a wide range of patient requested activities every day

- therapeutic support: We offer people a range of therapy and support that gives them hope things can get better

- transparency: We have open and honest conversations with patients and each other, and name the difficult things

An illustration summarising the 12 culture of care standards for all NHS funded mental health inpatient settings

The culture of care standards for each of these components are set out in the sections below.

In addition, the standards are aligned to 3 key approaches – trauma-informed, autism-informed and culturally competent care – to support the ambition for equality focused inpatient care.

Core commitments and standards for the culture of inpatient care

1. Lived experience

Standards

- all patients are supported to have a voice in their care

- all patients’ experiences are systematically measured, valued and used to improve care

- paid peer workforce at all levels are an integral part of the multidisciplinary team (MDT)

- lived experience leadership roles are at all levels of the organisation

- lived experience representative of the service type and local community is embedded in service design, quality improvement, governance and oversight

- infrastructure is in place to support people with lived experience in these roles, and designed by people with lived experience

What these standards mean in practice

“Communication is key. If changes are put in place in an inpatient unit make sure to get feedback from the autistic young people who experience these changes. Take into consideration what they think works well and any concerns they may have.”

Beth W, It’s Not Rocket Science, p51

Lived experience of mental illness, learning disability and autism, trauma and adversity, and service use is sought, listened to, valued and acted on at every level of the organisation. Alongside paid lived experience and peer roles, the infrastructure supports a broad range of voices to be heard, and prevents lived experience becoming assimilated or co-opted. Integrating lived experience takes the form of true co-production, not just consultation or engagement. All training is co-designed and co-delivered by people with lived experience.

Within our ward environment, we demonstrate how we value people’s lived experience, alongside professional or learned expertise, in everything we do. We respect individual patient’s perspectives and wishes in their care, including those of patients who feel let down or disappointed in our service so far or whose voices are often not easily heard.

We have robust methods to capture patient feedback and act on it; and patient experience (quantitative and qualitative) is measured as part of our quality assurance process. We aim to co-produce measures or use existing co-produced measures of experience, such as VOICE [5].

We have peer roles on our ward as an integrated part of our MDT – so that everyone can engage with multiple perspectives to challenge and improve practice – and value the distinctiveness of these roles. The fidelity to peer support is protected and peer workers do not participate in restraint or other coercive practices such as the compulsory administration of medication [6].

“Patients and their carers should be present, powerful and involved at all levels of healthcare organisations from wards to the boards of trusts.” [7]

We are committed to growing lived experience leadership roles across the organisation, including a patient director and patient safety partners, to ensure co-production across service design, quality improvement and oversight. Those in lived experience roles can access training and development, and have a clear career pathway, alongside opportunities to move into different roles. People with lived experience are employed at a range of bandings.

People in lived experience roles can also support staff through supervision and reflective spaces.

“Participants described a lack of understanding by decision makers and staff about the experiences of multiple disadvantage and discrimination which had contributed to their eventual admission to secure care. They mentioned that they needed someone to talk to who could empathise, acknowledge and understand their specific experiences as Black African and Caribbean men, such as a peer worker or advocate.”

NHS England. Developing the ‘Forensic Mental Health Community Service Model’ background information resource (2 of 5): Service user perspectives.

The lived experience workforce should reflect the communities they serve, and provide culturally competent support, recognising the importance of shared cultural identity in peer work.

We pay attention to every aspect of what it means to be a peer; for example, being a mum in perinatal services.

“Just knowing that there were other mums, it was just like the biggest comfort ever. I just felt like, oh my gosh I’m not the only one.” [8]

We recognise the emotional toll of lived experience work. All people in lived experience and peer roles, both voluntary and employed, are well supported, and reasonable adjustments are made, including part-time working and job share options. Support includes reflective practice and lived experience supervision, offered within the MDT and from a separate peer or lived experience space or structure [9].

2. Safety

Standards

- all people (patients, staff and visitors) feel safe on the ward

- we respect and protect people’s civil and human rights

- staff prioritise building therapeutic relationships to support patient safety

- people always receive a compassionate response when they feel unsafe

- the approach to safety is relational

- people’s mental health and physical health needs are understood and met (see also Needs led)

What these standards mean in practice

We take action to keep people (patients, staff and visitors) safe, protecting their physical, relational, emotional and cultural safety. We ensure people are safe from sexual and gender-based harm [10], and our facilities are safe for people at risk of harm to themselves or others. We believe people when they tell us they feel unsafe, or have experienced sexual or gender-based harm, and report incidents when they occur.

We protect and value time to build meaningful therapeutic relationships with patients as we know this, over the use of surveillance technology, keeps them safe in everything we do. One-to-one observation can be a way to spend time and be with the person, thereby building a therapeutic relationship [11]. Our focus is easing people’s discomfort and distress, and we recognise that having someone to listen 24/7 can shift a person’s perspective to one of hope for the future [12].

We are person centred [13] in our approach to safety. We ask patients and lived experience workers what makes them feel safe and what makes them feel unsafe on the ward; the former might include access to basic items such as a phone charger, hygiene products and information about the ward. We involve the person and their loved ones in safety planning. Where the person lacks the capacity to discuss what makes them feel safe, we seek information from their support network, patient record or community team, and listen to their feedback as we care for them.

“I was on 1:1 support and this often meant that there were men in my room overnight. Regular male staff were great, it’s easier if you know them, but it was often people I’d never met before. I asked to go home because I didn’t feel safe and it made me more stressed. They told me they didn’t have enough female staff.”

Emily, It’s Not Rocket Science, p98

We have consistent and safe staffing levels. Our staff feel safe from harm, and are psychologically informed, supported and trained to be alongside people in extreme states of distress or dissociation. They are supported to respond to people’s distress with compassion and without punitive approaches such as behavioural contracts, sanctions (criminal or otherwise) and withholding care [14].

“Risk assessment tools should not be used to predict future suicide or repetition of self-harm, or to determine who should or should not be offered treatment. The guideline suggests risk assessment should focus on the person’s needs and how to support their immediate and long-term psychological and physical safety.” [15]

We recognise the impact of racism, stereotyping and bias in assessment of risk and question the impact of such discrimination in decision-making about people’s safety. Therapeutic collaboration is prioritised in providing safe care, and positive risk-taking approaches [14] are not employed against people’s wishes, such as early discharge. We do not use risk assessment tools and scales to assess harm to self, and never tell people that they have capacity to take their own life. We adjust our care for differences in age and understanding, and can evidence this in practice.

Where we need to keep people safe from harming others, we recognise and prioritise the value of relational approaches to safety and security. We prioritise staff time, skill and confidence in being able to foster a relational approach to safety and security.

“Relational security is primary: women’s needs are more closely attuned to and respond better to ‘relational security’ rather than ‘physical security’. This requires staff to have a deep understanding of the women on the wards and how they respond to their environment and changes within it or planned transitions across them.” [16]

Multiple reports and Safeguarding Adults Reviews, such as that into the care of Joanna, Jon and Ben at Cawston Park, evidenced that the physical health care needs of autistic individuals and those with a learning disability are often neglected or ignored during mental health inpatient admissions, sometimes with devastating outcomes.

Staff are equipped to support people with their physical health needs, and understand the higher risk of premature mortality and co-morbidities and the issues of diagnostic overshadowing in this group.

3. Relationships

Standards

- staff take the time to get to know the people on their wards and build a trusting relationship with them

- staff are competent in building relationships with different people and responding compassionately to extreme states of distress

- staff understand and respond to different individuals’ needs, for example with reasonable adjustments

- the ward builds and maintains consistent relationships with people’s chosen support network

- people and families feel care is culturally competent and meets people’s diverse needs

- the organisation supports staff to protect and prioritise the therapeutic relationship

- the organisation supports the development of healthy team dynamics that positively impact on patient care and patient experience

What these standards mean in practice

Positive relationships between staff and the people they support are fundamental to a person-centred care environment. We recognise that trusting therapeutic relationships are the strongest predictor of good clinical outcomes [17, 18], and staff are supported to prioritise building relationships with patients over non-essential paperwork and other tasks. Training in relational approaches to care is available for all staff.

“Time with staff and time to talk to staff was the most common response when women were asked what helped them and their recovery.” [16]

“Empathy, respect and empowerment can be felt when an alliance is built on acceptance and trust. Without a therapeutic relationship, patients are a lot less likely to engage with and make effective use of mental health services and may be put off accessing services in the future.” [19]

We spend time with people in distress, irrespective of how the distress presents, and actively listen to and believe what they say. We consider this time alongside people as the most valuable in supporting patients to survive and manage their mental health crisis, and maximise its therapeutic potential.

We recognise the need to work particularly hard to build relationships and make collaborative decisions with people who lack capacity, and that it can take longer to listen to people who may communicate in complicated and unusual ways. We recognise how frustrating it must be for someone not to be heard and understood when they are already distressed and in a strange environment, and we actively support alternative and/or augmented methods of communication. Staff are skilled in the communication style that works for the person; see also 4. Staff support.

We also recognise that people report good experiences of care when staff are compassionate, caring and respectful, and are engaged and supported by staff in ways that help them feel valued and understood (including their cultural identity); good experiences reduce the use of coercive measures. Staff are supported to engage authentically and strong communication and interpersonal skills are prioritised in staff recruitment, development and training. Bank and agency staff are given the time to get to know people on the ward and build relationships with them.

“Compassion requires a reflexive ethos, an environment that prioritises therapeutic relationships, and challenging of policies and cultures that normalise oppression.” [20]

We take responsibility for the breakdown of relationships between staff members and patients, and we have co-produced procedures in place should this occur.

“… we know that the single greatest factor that supports resilience is stable and supportive adult-child relationships … the clinician is likely to – at least initially – be a surrogate for the stability and connectedness that her clients missed as children. …As clinicians, if we are attentive to the idea that the consistent, supportive relationship we have with our clients is itself the most critical intervention in helping clients recover from early trauma, then we are less likely to miss the important opportunities that may arise for showing that support, for offering co-regulation, and for providing stability. … “I see you, I hear you, and I believe you” is often the most potent way we will express to a client that they are finally being understood.” [21]

We respond promptly and compassionately to patient requests. We recognise that some patients may prefer to work with particular staff, perhaps because of a shared interest or cultural identity, and accommodate such preferences where possible. We embrace and recognise dependency as a positive aspect of trusting relationships, and we do not pathologise patient attachments to individual staff members.

Ward staff value forming good relationships with community staff and broader services within the local community, including voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations, peer groups, advocacy organisations, sports clubs and faith-based organisations. These relationships facilitate welcoming handovers as people approach transitioning back to the community from inpatient care. For example, rather than simply giving a person a leaflet about Mind, ward staff may offer: “let me call my colleague Sam at Mind and arrange to introduce you as I know they have a great weekly yoga class”.

4. Staff support

Standards

- staff have the practical and emotional support they need to remain compassionate, understanding and emotionally available. This is evident at every level of the organisation and underpinned by HR policies

- ward leaders have the skills and training to foster a compassionate culture on the ward

- freedom to speak up systems are in place for staff to raise concerns and be heard

- staff experience is systematically measured and used to improve care

- reflective practice is mandatory for all staff providing care on the ward, regardless of role

- we have enough skilled staff on the ward to deliver safe and therapeutic care

- staff know spending time with patients is a measurable priority, and that administrative tasks are never prioritised over providing compassionate care

What these standards mean in practice

We understand that safe and high quality inpatient mental health care relies on staff being alongside people in a lot of pain and distress. Witnessing human distress every day can take its toll on staff wellbeing, and therefore their ability to provide a compassionate response. We are committed to providing all our ward staff with the right practical support to protect their time to care, and with the right emotional support so that they can nurture the people they are working with as well as themselves [19].

This means staffing levels are safe for everyone, and staff have up-to-date, co-produced and meaningful training, and accessible, trauma-informed and culturally sensitive HR policies, including considering staff groups who experience inequalities (NHS Workforce Race Equality Standard, Workforce Disability Equality Standard, LGBTQ+ [22]).

“Incorporating a compassionate and restorative approach within supervision has been shown to have good outcomes for both staff and service users. For example, the use of a restorative model places value on how participants respond emotionally to the work of caring for others, a key component in the current healthcare climates.

The Professional Nurse Advocate (PNA) programme delivers training for registered nurses in restorative supervision across England.” [19]

Staff know themselves and recognise that reflection, self-awareness [23] and engaging with people are critical to delivering safe, therapeutic care. All staff working with people on the ward have a safe space that is open, supportive and honest to process their own feelings.

Mandated spaces run by trained facilitators and opportunities for reflective practice are built into the ward routines and meetings for all staff, and rotas ensure all staff can attend on a regular basis. Leaders model supportive and reflective leadership, and reflective practice is present at all levels in the organisation.

In line with the Nursing and Midwifery Council code of conduct and NHS England’s combatting racial discrimination against minority ethnic nurses, midwives and nursing associates policy, we identify and challenge all forms of racism and create an environment where all staff are treated as individuals and with dignity and respect.

We commit to the ward having visible leaders who are highly skilled communicators and can build and maintain a compassionate culture that is culturally competent, and take action when there are concerns. We encourage all staff to speak up if they have concerns and we ensure they feel safe to do so through supportive organisational systems.

Staff understand and are trained in how to communicate effectively with people who have differences in speech, language and communication needs. They are experienced in using a diverse range of communication methods and engage support from specialist speech and language therapists to further develop their skill in the different methods, so they can offer safe and therapeutic care to all patients, regardless of communication and interaction styles.

5. Equality

Standards

- the organisation understands its local population and takes action where certain groups are over- or under-represented in services. And where outcomes for particular groups are poor, we take steps to mitigate these and share learning

- patient experience and outcome measures are captured and analysed by protected characteristics (including for levels of restrictive practice)

- the organisation fosters connections with local community services, VCSE providers and other statutory organisations to take a collaborative approach in identifying and addressing health inequalities across the whole care pathway

- the organisation uses tools such as the Patient Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) and Advancing Mental Health Equality (AMHE) Framework to eliminate disparities in access, experience and outcomes

- the organisation ensures it meets Equality Act (2010) duties to people with a learning disability or who are autistic, and that their wider human rights are respected and protected [24]

- mandatory ongoing training for staff covers inequality and there is regular reflective space (see also Staff support) to discuss equity, intersectionality and impact of own identity

- the organisation’s workforce and leadership is diverse and inclusive, and reflects the diversity of the community it serves. Leaders take action to address any workforce inequality

Note on intersectionality

We recognise that who people are, and how society responds to them, is shaped by their individual rich and complex mix of identities and experiences. A person’s experiences within systems of inequality – from race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, poverty, age, diagnosis and other forms of discrimination – are cumulative and impact on how a person is treated on a ward, their outcomes and experience.

We must see beyond individual oppression and inequalities by making space to consider the complexity of people’s identities and understanding that people are affected in different ways. For example, a young black woman experiences high levels of restrictive practice during her inpatient stay. Rather than attempting to disentangle how each characteristic leads to this discrimination and inequality, we must explore how her gender, race and age intersect to impact on her experiences of inpatient care.

A recent Race and Health Observatory report identified that the average age of death is 34 for people from a minority ethnic community who have a learning disability; that is over 25 years younger than their white British counterparts. This intersectionality of race and learning disability is another example of how we must start to look at people’s lives differently.

Alongside the protected characteristics in the Equalities Act 2010, we suggest thoughtful consideration of the intersectionality between:

- looked after children

- young carers

- homelessness

- drug and alcohol dependence

- refugees

- people in contact with the criminal justice system

- people who experience domestic violence

- people who identify as trans*

The wheel of power/privilege is a useful tool to promote conversations about intersectionality. While it does not weight the individual characteristics, it facilitates an understanding of the complex interplay between people’s many different characteristics and experiences.

What the standards mean in practice

Our organisation/ward is inclusive; we value difference and do not agree with othering. We respect all people as citizens and valued members of their community. We are here for everyone when they need us, and understand how their background, protected characteristics, health conditions and where they live shapes who they are as people.

We take a systematic approach to understanding the communities we serve, who is over- and under-represented in our service, who is discriminated against and/or who has poorer experiences and outcomes. We take clear action in partnership with marginalised communities to address discrimination and inequalities in our service, and monitor the impact of our actions.

We measure patient experience (both quantitatively and qualitatively) through an equalities lens, and we prioritise these findings over activity-related data in determining our actions. We recognise that existing patient feedback mechanisms may not feel safe and trusted by all patients groups and therefore invest in patient and carer feedback mechanisms for racialised communities in line with the PCREF.

We are culturally competent and take a range of actions to counter systemic racism. Our focus is wider than increasing access for racialised groups, and we ensure everything we do is culturally sensitive by drawing on the PCREF to support cultural change across our services.

We are inclusive and accessible for people with a learning disability. We recognise our role in communicating with the person in a way that makes sense to them and take a strengths-based approach to supporting people.

We are autism-informed. We are aware of the prevalence of autism and neurodivergence in the population we serve and uphold our legal duty to ensure our environment and approaches accommodate autistic people [25].

We do not discriminate against people because of their diagnosis, particularly those given a diagnosis of personality disorder (PD). We do not separate people we have labelled ‘PD’ from those we understand have a serious mental illness, or use the label to deny people access to care and support (see section 6 Avoiding harm).

We do not make assumptions about people’s gender or their pronouns. We are trans*-inclusive and respect trans people’s choices on where they would like to receive treatment [26].

We provide age-appropriate care and treatment to children and young people, with staff trained and competent in understanding and responding to their specific developmental needs.

We provide a safe and accessible environment for trauma survivors, including of childhood sexual abuse and sexual violence, to disclose and access support as needed.

Three clear messages from the 2017 NHS England-commissioned project ‘Black Voices’ capturing the voices of 40 Black and Black British men detained in mental health secure care were:

- Decision-makers and staff lack understanding of how experiences of multiple disadvantage and discrimination contribute to admission to secure care.

- Many want someone to talk to who can empathise, acknowledge and understand their specific experiences as Black African and Caribbean men, such as a peer worker or advocate.

- Black men can find it difficult to engage in conventional programmes such as advocacy services, as they are not confident that these services are sufficiently aware or sensitive to their needs as Black men.

We recognise the current circumstances of many of those who face multiple disadvantages will have been shaped by long-term experiences of poverty, deprivation, trauma, sexual violence, abuse and neglect. Many also face racism, sexism and homophobia [27]. We understand these inequalities can intersect in different ways, and lead to homelessness, substance misuse, domestic violence, contact with the criminal justice system and mental ill health. We recognise the particular need for services to work collaboratively for those with multiple disadvantages.

6. Avoiding harm

Standards

- we acknowledge and avoid the harm and traumatisation that can occur when people are in hospital.

- there is a clear pathway of support for patients who have experienced abuse/harm, including access to advocacy

- we understand that restraint and coercion is harmful and we only use it as a last resort; that includes the use of blanket restrictions

- we do not use mechanical restraint

- our inpatient services meet the needs of trauma survivors in crisis

- we are trans*-accessible and inclusive (see also Equality)

What do the standards mean in practice

We acknowledge the risk of potential harm and traumatisation from being in a hospital setting [28], and seek to avoid this for people in our care. We do this through working to improve care together (as set out in Framework for involving patients in patient safety) and upholding patient rights, not by excluding some people from inpatient services.

“Older trauma survivors can experience re-traumatisation in care settings that provide reminders of traumatic events and/or present limitations to autonomy, choice, and control that are often essential to recovery. In addition, the onset of dementia can trigger the re-emergence of traumatic stress symptoms even where these have been dormant for many years. Common hospital care practices (for example, assisting with toileting and bathing) and environments (for example, locked wards) have been identified as potential sources of distress for older trauma survivors.” [29]

We validate, respond to and work to mitigate all forms of harm/traumatisation, both those that are significant and those from the everyday experiences of treatment on a ward that are inherent in inpatient settings; for example, being among distressed strangers and away from home. We understand the harm some of our practices can cause – for example, sectioning, restraint, seclusion and coercion – and that they can compound people’s previous trauma, oppression and/or experience of racism. We seek to use the least restrictive practices and only use them as a last resort, proportionately and in line with the law. We reflect together regularly as staff and patients about the way we use restrictive practices. We understand that both action and inaction can be harmful, and seek never to neglect people; we do not exclude based on diagnosis and we do not misuse the Mental Capacity Act (2005) to deny access to support.

We reduce our use of restrictive practices for all patients, keeping under close review patient groups that we know are at greater risk of avoidable harm; those subject to restraint inequality. These include trauma survivors, people who have been given a diagnosis of personality disorder, autistic people, people with a learning disability, people from racialised communities and people from LGBTQ+ communities. We provide trauma-specific support for people who have experienced trauma and abuse, and we connect with community-based services to provide continuity in this support and care.

“Ensure people are not inadvertently excluded because of service thresholds, positive risk and/or diagnosis.” [19]

When people or their families tell us they have been harmed while an inpatient, we hear and believe them, and have robust mechanisms to report harm and take appropriate action. We are accountable for any harm that occurs. We also have an independent support pathway for patients who are harmed so they can access support outside the trust if this is their preference. We raise safeguarding concerns with the local authority as necessary and/or support people to raise these themselves, ensuring access to independent advocacy where safeguarding reviews or enquiries take place.

7. Needs led

Standards

- we are needs-led, not diagnostically driven

- people are supported and encouraged to define their needs

- the MDT respects people’s individual understanding of their distress

- we validate patients’ feelings, and respect their culture, values and beliefs

- we take a capabilities approach and recognise that everyone has something to offer

- we meet the needs of people’s chosen support network

- patients’ needs and wishes are listened to in the admission and discharge process

What the standards mean in practice

Our services are set up with the prevalence and impact of trauma and adversity in mind. We believe what people tell us has happened to them and are equipped to offer a range of specific trauma interventions in response.

We strive to deliver inpatient care that meets people’s individual needs and in this we care about what matters to them. We do not rely solely on diagnosis or ‘clusters’. We respect people’s individual understanding of what is happening for them. While we may have our own framework or worldview to understand why people are in hospital (biological, medical, genetics, psychology, social, trauma, adversity, lifestyle, spiritual), we remain curious about their individual understanding and respect their right to make sense of themselves, and to reject ideas they consider are harmful to them.

When people may be experiencing a different reality to those around them, through hearing voices or experiencing unusual beliefs, the care team can find it more challenging to achieve a shared understanding with the person. Staff are supported to work compassionately with the person to establish their preferences (see also 3. Relationships).

We take a holistic capabilities approach to understanding people’s needs and strengths, recognising all aspects of what brings meaning and value to people’s lives [30]. We recognise the importance of fundamental needs like safe housing, financial security and physical health, and of the connections and relationships in people’s lives. We are also sensitive to people’s cultural identity and responsive to their spiritual needs and beliefs; what matters and makes sense to them. We care about the activities that are meaningful to the individual and help them build a life worth living, whether they be creative, leisure, education, volunteering or employment.

When people leave hospital their physical health should be at least as good, if not better, than when they were admitted. Staff are trained to understand patients’ physical health and care needs, including those of people with a learning disability or who are autistic, and in the routine day-to-day management of conditions such as cardiovascular disease, epilepsy, sleep apnoea and diabetes. They know where to get advice on caring for someone’s physical health, and people have access to a GP and more specialised care for their physical health. Staff also understand how to support and actively engage patients to manage their own long-term conditions and physical health while in hospital. Food options are always healthy and nutritious, and reasonably adjusted physical activity is always available.

“It would have been good to have a member of staff whose job is just focused on relatives and gets to know them well to support them. There are some very good staff but some don’t seem to have the time for families.” [31]

Staff are supported to respond to the needs of people’s chosen support network, including what help they may need with their own wellbeing. If the person does not want their support network involved in their care, staff take a common-sense approach to communication with the support network, recognising both the need to protect patient confidentiality and to show compassion to those who support the person.

8. Choice

Standards

- patients always have the choice to be present at meetings about them

- we adhere to the evidence-based approach of Open Dialogue and its key principles

- patients are supported to be involved in the decisions about them

- patients have choice in everyday decisions

- patients have the choice to collaborate in the writing of their notes and/or have access to their notes so that they know what has been recorded about them at any point during their inpatient stay

- patients have informed choice over their preferred treatment and who is involved in their care

- Where legislation overrides personal choice, this is explained in a clear and transparent way

- patients have the choice to be supported by people who know them well, by an advocate or by a peer worker

What the standards mean in practice

We understand that people often feel disempowered by coming into hospital, and we commit to prioritising patient choice over the needs of the service. People who use our services have control over everyday decisions, such as where they eat, what clothes they wear, when they spend time in the fresh air, who they spend time with and what time they go to bed.

Our expectation is also for everyone to have informed choice in every aspect of their care, including: admission and discharge; where they receive support; what treatments they receive; and who is involved in their care (the staff who work with them and their support network). People can choose to lead on producing a formulation of their distress and which staff members they would like to collaborate with in this process.

In line with the NICE guideline on shared decision making [NG197], we support people on the ward to make shared decisions about their care, working in an open and consistent way with their families, carers or advocates where the person wishes them to be involved. We use different communication approaches to support people’s understanding of decisions about them.

In line with the 7 Open Dialogue principles, we commit to never holding meetings (including ward rounds) about people on the ward without giving them the choice to be present; and the choice to work with staff on the completion of their notes or the option to access their notes at any point during their inpatient stay [32, 33, 34]. Any difference in opinion between staff and the person is described in the notes.

Where choice needs to be balanced with safety, developmental needs for children and young people or the best interests for people with a learning disability or autistic people, we consider individual needs and capacity relevant to the specific situation. Best interests decisions are person-centred, and well-communicated and well-documented.

Where people come into hospital against their wishes or where their care and treatment is stipulated by the Ministry of Justice, safeguarding or duty of care, we are transparent with them about how this can limit personal choice. Where choice in treatment is removed, we commit to work with the person to increase the choice they have in other aspects of their care. We are honest that we are denying choice and do not frame it as a shared decision or collaboration. This includes where we need to deny the choice to attend meetings or see own notes; and in such circumstances we seek to include the person’s views in the meeting and notes.

We embrace the contribution of advocates and peer advocates (see Figure 1 below), encouraging advocacy colleagues to be present within our services. We are proactive in ensuring patients know their rights, including under the Mental Capacity Act, and the advocacy available to them.

Figure 1: What people want from their advocate (reproduced with permission from NDTi A review of advocacy)

Image description: Diagrammatic representation of advocate qualities from the person’s perspective: is independent; is confident, skilled and knowledgeable; listens to family; upholds person’s rights and entitlements; understands the system and what’s possible; provides long-term, person-led, holistic support; has strong communication skills with professionals; has strong communication skills with the person they advocate for; builds relationships and rapport; is a named person and easy to access.

“I am a peer supporter with an NHS Foundation Trust. I help others to speak up using my own experience of being a self-advocate, having a learning disability myself.

When I was in a secure mental health hospital it was quite hard to speak up. When I asked to see an advocate people thought I wanted to make a complaint. But I wasn’t complaining, I just wanted help to understand my rights and speak up in my meetings. Some of my advocates were alright but some were just a ‘tick box exercise’.

I think advocacy is so important in secure services and in the community to show the person that their voice and opinion is valued and listened to. When I had a good advocate they came to my meetings, valued my opinion and put my views across to other people. People listened to my advocate.

Mental health advocates need to protect people’s rights, not be afraid to challenge the hospital and not get too close to the service, so they stay independent. They should have an open mind and probably need more training so they can support people with a learning disability and autistic people better.

I am out of hospital now and I do have an advocate in the community, but I don’t rely on them. I use my self-advocacy group to give me strength to speak up for myself and this is really important especially for people who do not have close family or friends. I also help to run focus groups with patients in secure services, to help people to get their voice heard and talk together.”

9. Environment

Standards

- the environment is inclusive and accessible, including through making reasonable adjustments where appropriate

- the environment is autism-informed, trauma-informed and sensory friendly

- comfort is prioritised alongside the space being clean and hygienic

- to prioritise relationships, there are no locked staff offices on the ward

- all people have open access to outdoor and green space

- the ward environment and procedures foster a sense of community, for example eating together

- the environment has been co-designed with people with lived experience and the needs and preferences of patients are evident in it

What do the standards mean in practice

We understand the impact the hospital environment can have on patient and staff wellbeing. We adapt our ward environment (thinking about sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, temperature, proprioception, interoception and pain [35]) to meet the needs of those admitted – cultural, disability and sensory needs (particularly for autistic people and trauma survivors) [25], ensuring it enables everyone to access the care they need and prevents adverse health outcomes.

“…our experience during site visits showed that if patients’ basic needs are met, and morale is positive, the condition of the physical environment itself becomes less important. However, in a negative culture with low morale, the maintenance issues and limitations and inadequacies of the physical environment are magnified.”

Midlands Clinical Senates Report on Therapeutic Inpatient Environment.

We want our inpatient space to be as soothing and comforting as possible for people who are often at their most vulnerable, and for it to reflect how we value staff and patients. This means the ward is clean, hygienic, well maintained and as least restrictive as possible, and everyone has access to outdoor and green spaces. It also means that the ward design both fosters a sense of community and protects people’s right to privacy, dignity and a family life, and promotes connection with life outside hospital. Wards need spaces suitable for families to visit, and children and young people’s services need spaces for education and, where possible, for families to stay overnight.

“Access to fresh air feels crucial for our recovery and to make life in hospital more tolerable. Regular access to open spaces should be planned and prioritised whether or not you have leave.”

Children and Young People’s Wishlist for Inpatient Care, Common Room.

Staff have a staff room on site that is equipped to allow them to take a relaxing and peaceful break, but there are no spaces where staff are shut away from people on the ward, such as locked staff offices. Staff are present in communal areas and available to spend time with patients and families for most of every shift. There are spaces for therapy, for private conversations and for visitors.

“One of the key things about the mother and baby unit that made it a more healing experience was that staff and patients cooked their meals together and ate together in a shared kitchen. This supported really normal and human conversations where I was seen and understood as a woman and a mum, not a diagnosis. It also meant the food was much better than the re-heated beige food served on acute wards!”

Person with lived experience of inpatient care in a mother and baby unit.

We recognise the importance of food for people’s wellbeing and cultural identity. We provide a variety of nutritious food options, which meet people’s physical health needs, cultural and religious requirements and preferences. Staff and patients have opportunities to cook and eat together.

10. Things to do on the ward

Standards

- people are supported to spend their time doing activities they enjoy

- patients decide which activities are on offer, including those that are culturally appropriate

- wards collaborate with VCSE and lived experience partners to deliver those activities

- activities support physical wellbeing

What the standards mean in practice

People admitted to our wards need the chance to do some of the things that they would do at home; many aspects of normal life should not cease on admission. People also need things to do to avoid boredom exacerbating their distress.

“Day to day life on the ward should as far as possible maintain a sense of normality and a connection to the outside world.”

“Life on the ward can often feel like living in a clinical bubble. But we need to be able to feel hopeful about what our future could look like outside hospital.”

“There should be a range and choice of regular activities and things to keep us occupied. This is so beneficial to help lift mood, find positivity, make connections with others and reduce loneliness. Boredom makes us more likely to dwell on negative or intrusive thoughts.”

Statements gathered by Common Room as part of the Children and Young People’s Quality Improvement Taskforce, 2023.

We have a clear, structured activity programme co-designed by people on the ward and we offer a range of patient-requested distraction and soothing activities, including those requested by people from racialised groups and/or other marginalised backgrounds. We work with local VCSE partners and the community to support this range of activities.

“A small number of women had been involved in charitable fundraising events and spoke powerfully about the positive impact this had on their hope for the future and on their sense of self-worth and purpose.” [19]

We can evidence that we provide opportunities for people to do things that matter to them, for example cooking, shopping, watching films, exercise. These activities are available 7 days a week, not restricted to 9am to 5pm [36], but should a person wish to watch TV or listen to music, for example, we facilitate this in a way that does not unduly compromise the comfort and wellbeing of others. We also understand that blanket restrictions can harm some people and we are committed to prioritising personalised choice over and above restrictions.

“The best activities are person-centred and have the flexibility to fit the changing and diverse range of needs that different people on the ward have.”

“When thinking about activities, ask patients ‘what you are interested in’. Try and meet people where they are – even if they want to be alone in their room, you can offer them ways to listen to music, or read, or journal, and not just see it as withdrawing.”

“What is right for one person will be different for someone else; what is a meaningful or enjoyable activities is subjective, so you are never going to get it perfect but it’s about trying to connect. A good way of getting it right is to have variety so you can reach a lot of people.”

Lived Experience Advisory Group members for ‘Co-producing activities that support health, recovery and mental wellbeing for people with psychosis on acute mental health wards and beyond.’ Researchers: Simpson, A., Foye, U., Regan, C., Brennan, G., Williams, J., Funder: London, Maudsley Charity.

People can participate in physical exercise every day and are encouraged to do so, by having the benefit explained to them in a meaningful way. A person’s mental state and staff availability are never used as reasons to deny access to physical activity.

We understand the value of people’s support networks. We are committed to being flexible in accommodating visitors. We facilitate access to culturally appropriate hairdressers, faith-based healers, ministers, prayer facilities and materials with which to conduct religious rituals, and other spiritual support networks.

11. Therapeutic support

Standards

- people have access to culturally sensitive support and treatment that is helpful

- people can choose their preferred therapy from a range of options, including trauma-specific therapy

- people have access to support around their social needs, including to maintain links with any community-based health and social care services and to plan for transition

What the standards mean in practice

We understand that being admitted to an inpatient setting can be a frightening and traumatising experience, and we are committed to making our services as therapeutic as possible.

“Mental health services take an evidence-based approach to treatment, but sometimes the simplest things like kindness and compassionate care are also extremely important for an individual’s care and recovery.” [37]

We never leave people in despair for any prolonged period, including during evenings and weekends, to repeatedly bang their heads on the walls or hit, bite or scratch themselves. They are always taken seriously and receive a compassionate and therapeutic response, one that does not rely only on medication.

We know that people from racialised communities and children and young people are often over-medicated rather than offered therapeutic support and ensure we consider and evidence how we mitigate this.

We ensure that therapeutic, sensitive support is available for people to access at any point during their inpatient stay, not just between the hours 9am to 5pm or at key points of stress such as admission and discharge, and can evidence how we provide this. We build strong relationships with those supporting people in the community, to ensure our patients are supported after discharge.

“There should be regular therapeutic intervention available to enable us to build skills to support our recovery. This intervention should be reviewed regularly with us and tailored to our individual needs.”

Young person with inpatient experience.

We give people choice in the evidence-based therapies and interventions they receive, especially trauma-specific therapies. We ensure our therapeutic offer is culturally appropriate and adapted to the needs of different groups of people, including people with a learning disability, autistic people and children and young people.

Where we cannot give people choice in therapy – for example, because completion of certain therapeutic programmes is a condition of admission as a restricted patient – we increase choice in other areas, from things to do on the ward, to social supports and relaxation approaches.

Where a person lacks the capacity to make an informed decision about the treatment they receive, we work with them and their support network (as appropriate) to consider what has worked well for them in the past, and what their wishes and preferences may be. Where we give treatment without the person’s consent or against their will, we are clear that this has not been a collaborative decision.

We ensure that social support is part of the therapeutic offer, including help accessing things like benefits, housing, vocation and food. We also work with VSCE partners to ensure that people are supported on the ward with issues relating to domestic and sexual violence, distress around being LGBTQ+, autistic or from a racialised and/or other marginalised groups. We provide resources and support to encourage a variety of peer support groups to meet on our ward to enhance our therapeutic offer to people.

12. Transparency

Standards

- we are honest with patients about our decision-making

- we have a regularly reviewed, co-produced charter that clearly sets out values and expectations

- the organisation has a transparent, compassionate, safe and responsive complaints process

- we are alert to how closed cultures can develop and take steps to avert this in partnership with people and families

- independent organisations and advocacy are welcomed onto the ward

- we are transparent about the names, roles and responsibilities of everyone working on the ward

What the standards mean in practice

We acknowledge that by the very nature of mental health hospitals, staff on the ward have power over patients. We commit to ensuring we have an open culture, recognise the value of having a welcoming environment in maintaining this culture, and take steps to mitigate the risk of closed cultures [38] developing. We welcome people from other organisations and a person’s support network and community onto the ward (in line with the person’s wishes). We recognise that services caring for people with a learning disability and autistic people are at a higher risk of a closed culture [39].

Staff, patients and their families meet daily to talk openly about their experiences of being on the ward, and we recognise this engagement as an important mitigation to closed cultures. We also regularly hold inclusive, shared learning events across our own and other organisations, and facilitate people on wards in different services to connect where it is safe for them to do so.

We are open and transparent about what happens on the ward and the care we provide.

“Coming into the visitors’ centre is such a difference. The staff are just brilliant. Friendly and kind. They smile and always make time for you. I can’t tell you how much difference this means to me.” [31]

We know that being on a ward with strangers can be frightening, so we try and familiarise people with who the staff are (including agency staff, advocates and visiting VSCE staff) by having visual displays showing, ideally, a photograph of each staff member along with their name, role, responsibilities and some information about them (see Safewards’ Know each other guidance). We also have freely available information describing the different mental health, learning disability and autism services within the organisation.

We take particular care to communicate information at times of transition, ahead of admission and in the run up to discharge from the ward. All our communications are accessible to their recipients and available in a range of formats to meet people’s needs.

We have a safe, culturally appropriate and accessible complaints and advocacy process for both staff and patients so they can escalate concerns without fear of this negatively impacting on them. We clearly signpost to our complaints process, and can evidence how we help people to access it, especially those who do not communicate in traditional ways, such as children or people with a learning disability.

We embrace advocacy services as an integral part of the service to patients and ensure patients are supported to access independent advocacy where they wish to. We ensure marginalised groups, for example people with a learning disability and autistic people have the same access to advocacy as other groups [40], and that patients have access to culturally competent advocacy.

We offer people a range of ways to share their experiences of being on our wards, including independent options, to acknowledge that sometimes people do not want to give feedback directly to staff. We have a clear process and pathway to support patients who have been harmed on our wards and no longer feel safe in the organisation to access independent support, both legal and psychological.

References

- Braithwaite J, Herkes J, Ludlow K, et al (2017). Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open 7(11).

- West M, Dawson J (2012). Employee engagement and NHS performance. The King’s Fund.

- Adams R, Ryan T, Wood E (2021). Understanding the factors that affect retention within the mental health nursing workforce: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. Int J Ment Health Nurs 30 (6): 1476-1497.

- Dickens G, Picchioni M (2011). A systematic review of the terms used to refer to people who use mental health service: User perspectives. Int J Soc Psychiatry 58 (2): 115-122.

- Evans J, Rose D, Flach C, Csipke E, Glossop H, Mccrone P, Craig T, Wykes T (2012). VOICE: developing a new measure of service users’ perceptions of inpatient care, using a participatory methodology. J Mental Health 21(1): 57-71.

- Holley J, Gillard S, Gibson S (2015). Peer worker roles and risk in mental health services: A qualitative comparative case study. Commun Mental Health J 51: 477-490.

- National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England (2013). Berwick review: A promise to learn – a commitment to act: improving the safety of patients in England. Department of Health and Social Care.

- Griffiths J, Lever Taylor B, Morant N, et al (2019). A qualitative comparison of experiences of specialist mother and baby units versus general psychiatric wards. BMC Psychiatry 19(1): 401.

- National Survivor User Network (2021). Lived Experience Leadership – Mapping the Lived Experience Landscape in Mental Health.

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2020). Standards and guidance to improve sexual safety on mental health and learning disabilities inpatient pathways.

- Rooney, C (2009). The meaning of mental health nurses experience of providing one-to-one observations: a phenomenological study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Learning 16(1): 76-86.

- Gill F (2014). The transition from adolescent inpatient care back to the community: Young people’s perspectives. London: University College London.

- McCormack B, McCance T (2010). Person-centred nursing: Theory, models and methods. Oxford: Blackwell.

- NHS England position on serenity integrated mentoring (SIM) and similar models

- Mental health blog (2022). Exclusion, coercion and neglect: the neoliberal co-option of positive risk-taking.

- NICE (2022). Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence [NG225].

- Pashley S, Denison S, Moore H ( April 2018). Exploring the lived experience of women in secure care services. National conference: Women in Secure Care, London

- Duncan BL, Miller SD, Wampold BE, Hubble MA, eds (2010). The heart and soul of change: Delivering what works in therapy, 2nd edn. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Gilburt H, Rose D, Slade M (2008). The importance of relationships in mental health care: A qualitative study of service users’ experiences of psychiatric hospital admission in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res 8: 92.

- NHS England (2022). The mental health nurse’s handbook

- Liberati E, Richards N, Ratnayake S, Gibson J, Martin G (2023). Tackling the erosion of compassion in acute mental health services. BMJ 382: e073055.

- Kain K, Terrell S (2018). Nurturing resilience: helping clients move forward from developmental trauma, an integrative somatic approach. North Atlantic Books, p229.

- The King’s Fund (2023). LGBTQ+ staff and patients deserve better from the NHS.

- Kirsten J (2008). Exploring self-awareness in mental health practice. Mental Health Practice 12(3): 31-35.

- NHS Improvement (2018). The learning disability improvement standards for NHS trusts.

- Doherty M, McCowan S, Shaw SCK (2023). Autistic SPACE: a novel framework for meeting the needs of autistic people in healthcare settings. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 84(4).

- Újhadbor R, Chuck E, Gohlan N, et al (2022). recommendations for trans*-inclusive healthcare. King’s College London.

- Making Every Adult Matter. About multiple disadvantage.

- Thibaut B, Dewa LH, Ramtale SC, et al (2019). Patient safety in inpatient mental health settings: a systematic review. BMJ Open 9: e030230.

- Couzner L, Spence N, Fausto K, et al (2022). Delivering trauma-informed care in a hospital ward for older adults with dementia: an illustrative case. Front Rehabilitat Sci 3: 934099.

- Nussbaum M (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- NHS England (2018). Carer support and involvement in secure mental health services: A toolkit

- Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin C-T (2015). Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Internal Med 175 :856–8.

- Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al (2016). Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform 7: 446–60.

- Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al (2011). A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc: 1428–35.

- NHS England (2023). Sensory-friendly resource pack.

- NICE (2011, last updated 2019). Quality standard [QS14]. Service user experience in adult mental health services.

- Moore P (2022). One act of kindness can change another person’s future. NHS Voices blogs

- CQC (2022).Our work on closed cultures.

- CQC inspections and regulation of Whorlton Hall 2015-2019: an independent review

- Mercer K, Petty G, NDTi (2023). A review of advocacy for people with a learning disability and autistic people who are inpatients in mental health, learning disability or autism specialist hospitals.

- Lomani J, Alyce S, Aves W et al, in collaboration with Survivors Voices (2022). New ways of supporting child abuse and sexual violence survivors: A social justice call for an innovative commissioning pathway.

Glossary

|

Co-production | Co-production is an ongoing partnership between people who design, deliver and commission services, people who use the services and people who need them. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2019). Working well together: Evidence and Tools to enable co-production in mental health commissioning. |

|

Diagnostic overshadowing |

Diagnostic overshadowing is a concept in healthcare where a person’s symptoms are automatically attributed to a single condition, such as a disability or mental illness, without fully exploring, considering or diagnosing alternative or co-existing conditions. |

|

Locked staff offices |

Office spaces within the main ward environment that are separated from and closed/locked to patients. This term does not include locked office spaces that are separate from the main ward environment where patients are. |

|

Risk assessment tools and scales |

In this guidance, we refer to tools and scales to assess risk of harm to self, as per NICE guideline 225 Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence, section 1.6. |

|

Support network |

Person, group of people, community or organisation that provides emotional and/or practical support to someone in need. A support network can be made up of family members, friends, colleagues, advocates, peers, volunteers, health and social care professionals, or supportive online forums or social networking sites. |

|

Trans* |

As used in this guidance, an umbrella term for the range of identities across the gender identity spectrum that do not conform to the cis-normative, binary model of gender. The asterisk liberates us from expectations and the restrictions placed on our lives by rigid societal gender norms. It symbolises how a person’s gender can morph and change as we grow in our humanity. (This definition is drawn from Recommendations for Trans* Inclusive Healthcare) |

Appendix: design group membership

- Tim Kendall, Co-chair and National Clinical Director for Mental Health, NHS England

- Cassie Lovelock, Co-chair and Expert by Experience

- Khudeja Amer-Sharif, Expert by Experience

- Tom Ayers, Director, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Royal College of Psychiatrists

- John Baker, Chair of Mental Health Nursing, University of Leeds

- Kelly Barker, Chief Operating Officer, Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust

- Dan Beale-Cocks, Expert by Experience

- Joanne Bosanquet, CEO, Foundation of Nursing Studies

- Geoff Brennan, Safewards Clinical Supervisor, King’s College London

- Mel Bruce, Psychologist, Specialist Advisor Clinical Quality, Learning Disability and Austism Programme, NHS England

- Mary Busk, Expert by Experience

- Paul Calaminus, Senior Programme Manager – Quality Transformation, NHS England

- Prathiba Chitsabesan, National Clinical Director for children and young people’s mental health; Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist

- Jill Corbyn, Founder and Director, Neurodiverse Connection

- Marie Crofts, Chief Nurse, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust

- Rebecca Daddow, Head of Adult Secure, National Specialised Commissioning, NHS England

- Charmaine DeSouza, Chief People Officer, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust

- Sahil Dodhia, Senior Project Manager and Expert by Experience, NHS England

- Caroline Donovan, National Advisor to Quality Transformation Programme

- Conor Eldred-Earl, Expert by Experience

- Mark Farmer, Expert by Experience

- Alex Hamlin, Lead Psychologist for Learning Disability Services, Humber Teaching NHS Foundation Trust

- Helen Hardy, Head of Mental Health, East of England Region, NHS England

- David Harling, National Deputy Director of Learning Disability Nursing, NHS England

- Liz James, Head of Nursing for Positive Practice, Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust

- Stephen Jones, Professional Lead for Mental Health, Royal College of Nursing

- Elizabeth Kirby, Senior Project Manager, Quality Transformation, NHS England

- Aji Lewis, Expert by Experience

- Jo Lomani, Senior Project Manager and Expert by Experience, NHS England

- Kate Lorrimer, Deputy Head of Quality Transformation (Quality of Care), NHS England

- Sarah Markham, Expert by Experience

- Tim Mellard, Matron, South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- Salli Midgley, Director of Nursing, Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust

- Sam Mongon, Head of Transformation, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust

- Debra Moore, Deputy Head of Quality Transformation (Redesign), NHS England

- Maria Nelligan, Interim Executive Director of Clinical Transformation, Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust

- Peter Oakes, Psychologist

- Mary Ryan, Expert by Experience

- Ashok Roy, Consultant Psychiatrist, LD, Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership Trust

- Melissa Simmonds, Race Equity Community Leader, Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Trust

- Alan Simpson, Professor of Mental Health Nursing, King’s College London

- Dwayne Smith, Expert by Experience

- Lade Smith, President, Royal College of Psychiatrists; Consultant Psychiatrist

- Sal Smith, Expert by Experience

- Tasha Suratwala, Expert by Experience

- Claire Swithenbank, Regional Head of Learning Disability and Autism, North West Region, NHS England

- Peter Thompson, Director College Centre for Quality Improvement, Royal College of Psychiatrists

- Giles Tinsley, Programme Director for Mental Health, Midlands Region, NHS England

- Kati Turner, Expert by Experience

- Jacky Vincent, Executive Director of Quality and Safety (Chief Nurse), Hertfordshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

- Emma Wadey, NHS England, Head of Mental Health Nursing

- Ellie Walsh, Navigo

- Gareth Watkins, Expert by Experience

- Mark Weaver, Chief Medical Officer, Black Country Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

- Nicky Windle, Senior Programme Manager – Quality Transformation, NHS England

- Anne Worrall-Davies, Interim National Clinical Director, Learning Disability and Autism Programme, NHS England

- Debbie Wood, Gareth Watkin’s co-worker

With thanks to the many additional people who provided feedback on the draft versions.

Publication number: PRN00826