Introduction

1 million people in the UK are unable to speak English well, or at all.

People who speak little or no English are more likely to be in poor health, have a greater likelihood of experiencing adverse events and of developing life-threatening conditions and tend to have poorer access to and experiences of healthcare services than people who don’t have language barriers.

They can struggle at all points of their journeys through healthcare.

Translation and interpreting services for community languages are inconsistent across the NHS.

Support for them by NHS commissioners, national programmes and NHS trusts is variable and the lack of high quality, appropriate and accessible services is stopping people from engaging with the healthcare they need.

NHS organisations, including commissioners and trusts, have legal duties to provide accessible and inclusive health communications for patients and the public.

These include requirements under the Equality Act 2010 and the NHS Act 2006, as amended by the 2022 Act.

What is the framework for?

This framework is designed to support the provision of consistent, high-quality community language translation and interpreting services by the NHS to people with limited English proficiency.

Community languages are defined as languages used by minority groups or communities where a majority language exists (for example, English in the UK).

It should be used as a framework for action across the NHS, including by NHS trusts and integrated care boards (ICBs).

In primary care, it supplements the existing guidance for commissioners on interpreting and translation services and should be used alongside it.

A note on scope

The framework covers the translation of written text (for example on NHS websites, posters, and video sub-titles) and spoken language interpreting.

It doesn’t cover British Sign Language (BSL), which is now recognised as an official language in England.

NHS guidance on how to make services and communications more accessible to those with disabilities is set out in other guidance such as the Accessible information standard.

This provides a consistent approach to identifying, recording and meeting the information and communication needs of people with a disability or sensory loss and sets out the steps healthcare providers should take to meet these needs.

Policy context

Concerns have been raised repeatedly about access to translation and interpreting support in the NHS.

This includes several investigations by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB), which has since been succeeded by the Health Service Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB).

In 2023, HSIB investigated how written patient communications were used in clinical booking systems. It recommended that NHS England develop a standard to help providers offer appointment information in languages other than English.

A key case involved a child from a Romanian-speaking family who had been referred for an MRI scan that required a general anaesthetic.

The family received spoken translation support, but written communications were not translated.

The trust’s hybrid booking system did not support letters in other languages, and there was no policy requiring staff to consider translating written documents.

Although the trust knew the family needed translations, appointment letters were only sent in English.

The family understood the basic details – time, date and location – but did not realise the child needed to fast beforehand. As a result, the scan was cancelled.

The referral was then lost in the system, leading to an 11-week delay. When rebooked, the child again had not fasted, and the scan was cancelled a 2nd time. It was finally carried out the following day.

The child died. Although there was no suggestion that identifying the cancer earlier would have prevented this, the case highlighted serious patient safety concerns around written communication in community languages.

HSIB’s report made a safety observation suggesting NHS providers should explore ways to translate appointment letters for people whose preferred language is not English.

NHS England response

In response to the report, NHS England:

- reaffirmed its commitment to improving patient safety for people who speak little or no English

- recognised the need to reduce disparities in access, experience and outcomes

- made clear that responsibility for commissioning translation and interpreting services sits with ICBs and trusts, who are best placed to meet local needs

In 2023/24, NHS England also carried out a strategic review. This built on the safety investigations and examined broader issues in translation and interpreting across the patient pathway. It included an options appraisal for future action. The findings have informed this framework.

More fundamentally, these issues are central to the NHS’s mission to provide a comprehensive health service that is available to everyone.

The NHS Constitution says the NHS has a social duty to promote equality through the services it provides, focusing on groups where improvements in health are not keeping pace with the rest of the population.

It also says NHS services must reflect, and should be co-ordinated around and tailored to, the needs and preferences of patients, their families and their carers.

Lord Darzi’s independent investigation of the NHS in England (September 2024) highlights that, in many areas of healthcare, this is not happening.

Darzi says that, “the inverse care law seems to apply: those in greatest need tend to have the poorest access to care”. Inconsistent provision of translation and interpreting services is one key contributing factor for many people with limited English proficiency.

In the context of the government’s plans to develop a 10-year plan for health and its wider commitment to a mission-led approach to government, there is an opportunity to make a real difference to inequalities.

The evidence for change

People who speak little or no English face significant barriers and delays in receiving care, which puts their health at risk and contributes to health inequalities.

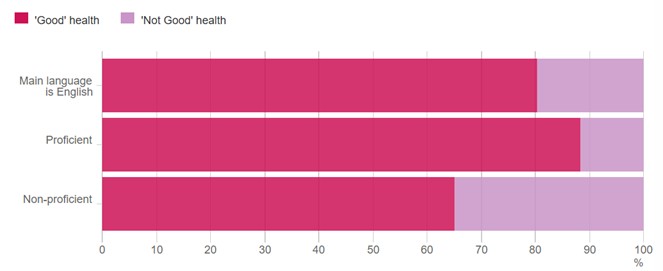

In 2011*, only 65% of people who could not speak English reported good health, compared with 88% of those who spoke English well (see Figure 1).

[*Responses are taken from the 2011 census; this data was not available from the 2021 census.]

More information is available in Annex A.

The cost to the NHS

Inadequate translation and interpreting services create significant financial pressures on the NHS. While data is limited, the cost is likely to run into millions of pounds, with inefficiencies including:

- late presentation of disease symptoms (for example, cancer) and therefore more expensive treatment for advanced disease

- more patients missing appointments (‘did not attends’ or DNAs)

- more use of emergency departments because of language barriers when accessing primary care

- more emergency admissions because of poor condition management, often linked to misunderstanding medication or treatment plans

- medication errors – these cost the NHS over £98 million a year, cause or contribute to 1,708 deaths, and use up more than 181,000 bed-days

- overuse of diagnostic tests, invasive procedures or prescriptions because clinicians cannot communicate effectively with patients

- increased potential litigation costs because patients with language barriers are more likely to experience adverse events in hospital (the NHS spent £1.63 billion in 2017/18 on patient safety litigation).

5 areas of action

The next sections outline specific actions for primary care, NHS trusts, ICB commissioners and national programme teams across 5 areas of action:

- Leadership, quality and professional standards.

- Access and barriers to services.

- Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights.

- Digital opportunities and challenges.

- Safety, confidentiality and consent.

1. Leadership, quality and professional standards:

There is a need for consistent approaches to the procurement, funding, monitoring and management and stronger standards and clearer accountability for interpreter qualifications and professional conduct.

This calls for both top-down leadership and bottom-up responsibility, with every level of the system playing a part.

Strong engagement and feedback mechanisms with communities and users are essential.

This will put co-production at the centre of service design, helping services to continually improve, adapt to local needs and deliver better quality.

2. Access and barriers to services

We need to promote translation and interpreting services (and explain how to access them) in users’ languages.

Services should be designed to overcome local barriers to access and to meet local needs. Users should understand their right to access these services.

Staff training will play a part: raising awareness of the services available to patients, clarifying when and how to book them and helping staff help users understand their rights.

3. Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights

During the engagement exercise led by National Voices, which informed this guidance, people with limited English proficiency described negative experiences when using NHS services.

They spoke about discrimination and lack of cultural sensitivity, which may not be intentional.

This undermines patient trust, reduces attendance at appointments, harms health outcomes, and makes it harder to engage patients with preventative care.

We need to educate staff and patients about the right to access services, establish clear escalation routes to address discrimination, and train staff to deliver culturally sensitive care to people with little or no English.

4. Digital opportunities and challenges

People with limited English proficiency are more likely to live in the most overall deprived 10% of neighbourhoods in England and therefore face higher risks of being digitally excluded.

It’s therefore vital that the dual nature of technology – both as an enabler and a source of inequity and mistrust – is always carefully considered when developing digital solutions.

Technological advances should be co-produced with people with lived experience and be guided by the Inclusive digital healthcare framework.

There are concerns about the appropriate use of AI translation apps that are currently widely used across the NHS to communicate with patients with limited English proficiency.

While translation apps provide a convenient, familiar and timely means of translation, they can also carry risks, particularly regarding accuracy and the potential impact on patient safety.

5. Safety, confidentiality and consent

If a translation is inaccurate, or not presented in its entirety, a patient cannot truly understand their choices in shared decision making or provide their informed consent to a treatment plan.

We must ensure that patient confidentiality and safety is a priority when using translation and interpreting services – and address the risks of using apps and informal interpreters as methods of communication with people with limited English proficiency.

Recommendations for primary care settings

Actions for primary care

Leadership, quality and professional standards

- Appoint a local or primary care network (PCN) lead to champion interpreting services, ensuring accountability, adherence to standards, and continuous quality improvement at the local level.

- Establish feedback systems for patients and staff to identify issues and provide ongoing input into the improvement of translation and interpreting services.

Access and barriers to services

- At practice or PCN level, collaborate with the ICB on any procurement of new interpreting services to ensure they respond to local population needs and ensure quality provision.

- Improve staff awareness of the right of patients to have interpreting support (including among receptionists and care co-ordinators).

- Use the primary care electronic record to record language need at the earliest opportunity and include language need in referrals to other services. Maximise recording of language need across the practice population in the electronic patient record (EPR).

- Support new and existing practice staff to understand and improve the operational processes for accessing interpreting services.

Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights

- Establish clear escalation pathways within the services to address and resolve incidents of discrimination, ensuring accountability at a local level, where language rights are incorporated.

- Involve patients and communities in coproducing the development and improvement of interpreting services and other equity-focused measures, ensuring cultural sensitivity and inclusivity.

Digital opportunities and challenges

- Record language need in the primary care electronic record as early as possible, include it in referrals, and maximise recording across the practice population in the EPR.

Safety, confidentiality and consent

- Develop or adopt translated consent and confidentiality forms at the local level to ensure patients with limited English proficiency fully understand and can participate in the consent process. Local consent forms should adhere to national standards.

- Confidentiality – interpreters should complete confidentiality forms to support patient trust and confidence.

Case study in primary care

GP practices across Frimley translate appointment reminders to reduce ‘did not attends’ (DNAs).

Background

GP practices across Frimley worked with Frimley ICB to translate appointment reminder text messages to patients with limited English, aiming to reduce DNAs.

The challenge

Standard English reminder texts were less effective in culturally diverse areas, where DNAs remained high.

The approach

Frimley ICB partnered with Manor Park Surgery and Mayfield Medical Practice to translate reminder texts into the 6 most common languages in the local population:

- Hindi

- Nepali

- Polish

- Punjabi

- Ukrainian

- Urdu

These languages were identified by the GP practices from patient records.

In this case study, bilingual NHS staff checked AI-generated translations to ensure accuracy and check nuances.

Reception and administrative staff were trained using an existing process developed by Mayfield Medical Practice to efficiently send the correct versions of the messages to the correct patients.

The process drew on EMIS, Accurx and patient record information to automatically source patient mobile numbers.

The messages were also saved in English on clinical records, ensuring both versions were available for internal review and follow-up.

Impact

Since November 2023, practices have reported positive patient feedback and a drop in DNAs.

There has been increased engagement among patients with limited English proficiency, including with immunisations and screening.

What people said

An anonymous patient talking about a family member or friend: “This simple but impactful change made them feel understood and valued.”

GP practice staff: “The introduction of text messages in Punjabi and Urdu has been a significant and reassuring step in removing language barriers for our patients.”

Tips for success

- Collaborate across practices and ICBs to maximise impact.

- Raise awareness of the importance of translated communication across all staff – and prioritise it so it is not seen as an ‘add on’ to NHS services.

What next?

The team plans to add more languages and dialects and share resources with other NHS services, including maternity and chest clinics.

They are inviting other GP, dentist and pharmacy practices across England to get involved.

Recommendations for NHS trusts

Actions for NHS trusts

Leadership, quality and professional standards

- Ensure senior, director-level leadership and accountability for the provision of quality translation and interpreting services within the trust.

- Maintain governance oversight of translation and interpreting services under a board-level committee, ideally the quality committee.

- Ensure there is a policy in place for translation and interpreting services and a set of clear protocols or standard operating procedures (SOPs).

- Apply service improvement methods to develop and strengthen services, using feedback mechanisms for patients and staff to help drive meaningful improvements.

- When procuring for a new translation service provider, ensure qualification and training standards are defined and the interpreters are registered (for example, with professional bodies such as the National Register of Public Service Interpreters). Build quality metrics that can be regularly monitored into contracts.

- For large trusts with significant language needs across the catchment area, the trust involved may want to consider establishing an in-house interpreting service. The case study outlined below provides an example of a trust where volunteer and bank interpreters were used to bridge the language gap successfully.

Access and barriers to services

- Make sure that any new procurement of translation and interpreting services is based on the needs of the population the trust serves and focuses on quality as well as cost.

- Develop and support trust staff so that they understand patients’ rights to interpreting support and local procedures for accessing them.

- Review and update referral templates for use by primary care to ensure they include the language needs of the patient.

- Review and develop local methods for accessing interpreting services, including appropriate balance between phone and face-to-face interpreting.

Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights

- Establish clear escalation pathways within services to address and resolve incidents of discrimination, making sure language rights are included and accountability is in place at a local level.

- Actively involve patients and communities in coproducing and improving interpreting services and other equity-focused measures, ensuring cultural sensitivity and inclusivity.

Digital opportunities and challenges

- Ensure patients’ language needs, preferences about the gender of interpreters, and other communication preferences are accurately recorded in patient records.

- Note the risks and liability issues over the use of AI interpreting tools and take account of planned policy briefings from NHS England or the Department of Health and Social Care on the use of these tools in clinical settings. Ensure any use of AI tools for interpreting only operate in the context of clearly defined trust policy and risk assessment.

Safety, confidentiality and consent

- Develop translated consent forms at the local level to ensure patients with limited English proficiency fully understand and can participate in the consent process. To maintain consistency and quality, local consent forms should adhere to national standards.

- Align delivery with the National patient safety healthcare inequalities reduction framework, which sets out 5 principles to reduce patient safety healthcare inequalities across the NHS.

NHS trust case study

Hybrid hospital interpreting model improves patient outcomes.

Background

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS trust set up a hybrid model for interpreting services, combining professional in-house interpreters with external services.

The challenge

In 2014, a patient experience review highlighted issues with the trust’s translation and interpreting services, including patient complaints, rising costs and issues with quality.

The approach

Following a successful business case, the trust piloted an in-house bank of Polish interpreters in 2015, later expanding to other languages.

Volunteers received Level 3 interpreting training and supervision, with some progressing to paid roles.

The model includes trained volunteers, professional bank interpreters and back-up support from external providers.

An internal booking system ensures a fast response to urgent requests and better co-ordination between interpreters, clinicians and patients.

The trust partnered with the International School of Linguists to strengthen interpreter training.

Both volunteer and professional interpreters were invited to workshops to share each other’s experiences, learnings and successes.

Impact

As of March 2024, the service has 87 interpreters and 3 administrators, offering support in 59 languages and managing 25,000 bookings per year.

Between 2015 and 2021, it saved almost £1 million compared to 2014/15 costs.

What people said

John Cipko, interpreter: “The satisfying thing is feeling like I’ve helped people, and getting thanked not just by the client but also the doctors and consultants. They often tell me that without my help they would have struggled to help the patient.”

Tips for success

- Train people from different occupations.

- Academic linguistic qualifications are not necessary.

- Adapt admin and IT systems to support a blended model of interpreting services.

What next?

The service model will be refined and made more efficient.

The in-house translation and interpreting service will work closer with clinical teams, ensuring that face-to-face interpreting is made a priority during higher risk clinical interactions.

Telephone interpreting will become a prioritised channel for more routine appointments.

Recommendations for ICBs

Actions for ICBs

Leadership, quality and professional standards

- Ensure director-level leadership and accountability for the commissioning and contracting of translation and interpreting services for all services provided across the ICB’s footprint.

- Involve patients and communities in the development and improvement of local interpreting services through co-production, ensuring diverse voices are included to reflect local needs and address potential gaps in service provision.

- Work with PCNs to apply quality and service improvement methods to develop and strengthen services, using feedback mechanisms for patients and staff to help drive meaningful improvement.

- When procuring for a new service provider, ensure qualification and training standards are defined and interpreters registered (for example, with professional bodies such as the National Register of Public Service Interpreters). Build quality metrics that can be regularly monitored into contracts.

- Ensure any procurement of new interpreting services for primary care takes full account of local population needs and drives quality of service provision, not just cost factors.

Access and barriers to services

- Undertake a population-level needs assessment for community languages at system or place level, working with local community organisations and public health.

- Work with PCNs to review data on use of interpreting services, with a focus on improving access.

- Help improve awareness among practices and PCNs of local patient need for interpreting services and the procedures to access services.

Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights

- Involve patients and communities in the co-production and improvement of interpreting services in primary care, making sure they are culturally sensitive and inclusive.

Digital opportunities and challenges

- Capture and analyse patient data at the local level to identify trends and patterns in the use of interpreting services. Use these insights to optimise service delivery and meet demand.

Safety, confidentiality and consent

The National patient safety healthcare inequalities reduction framework sets out 5 principles to reduce patient safety healthcare inequalities across the NHS.

It outlines opportunities for implementation that local teams and ICBs can take up and the work NHS England is doing nationally to support this.

The principles align with the aims of NHS England’s patient safety strategy and the Core20PLUS5 approach (both for adults and for children and young people) to addressing healthcare inequalities.

The National patient safety healthcare inequalities reduction framework is for all NHS providers and their staff – particularly leaders, managers and educators implementing strategies to foster a culture of inclusive, safe care.

ICB case study

Strengthening translation and interpreting services by reducing fragmentation and improving access.

Background

An internal review found major gaps in Hampshire and Isle of Wight ICB’s translation and interpreting services in 2022/23, with areas like Portsmouth having 100% face-to-face provision at one site, while other areas had no real access. There were also billing and contract errors.

The challenge

Only 101 of 1,082 eligible primary care sites had language support.

Around 106,000 non-English speakers were at risk of poor access to services, leading to delayed care and higher pressure on emergency services.

The approach

The ICB took a system-wide approach by:

- conducting a needs assessment using Office for National Statistics language survey data, ethnicity mapping data, and local intelligence on diverse communities

- moving to a single spoken language provider in December 2023, who provided a robust utilisation reporting platform, and moved to a per-request basis for face-to-face provision with use guidelines

- raising awareness and providing guidance to general practices

- simplifying access by assigning unique ID numbers to each GP practice and place-specific IDs for pharmacy, optometry and dentistry

Impact

Between 2022 and 2024, service usage rose from 67,375 to 265,668 minutes.

The ICB improved access and coverage across all boroughs, reduced costs and received positive feedback from partners.

Tips for success

- Conduct regular question and answer sessions with stakeholders to raise awareness of available services and understand local problems. Generate local guides and FAQs and publicise widely.

- Assign unique IDs to practices, which helps streamline the process of accessing services.

- Engage with local forums and stakeholders and leverage digital platforms such as SHAPE to gather insights.

What next?

The ICB will review whether to procure spoken and non-spoken (BSL) interpreting services together or separately, expand client IDs from general practices to pharmacy, optometry, and dentistry and seek wider buy-in for a system-wide language service proposal.

Integrated care system case study

Southeast London foreign education programme – Improving patient experiences of maternity and neonatal care.

Background

The Southeast London Local Maternity and Neonatal System launched a pilot in 2023 to improve maternity care for people with limited English by delivering online education in multiple languages.

The challenge

Language barriers can lead to poorer outcomes and negative care experiences in maternity services.

The local maternity and neonatal system aimed to improve access to information and patient confidence.

The approach

The local maternity and neonatal system worked with stakeholders to:

- identify 6 key languages – Spanish, Portuguese, Somali, Romanian, Arabic, and French – using local data

- develop a 2-part monthly course in these languages, tailored to cultural needs

- train 16 bilingual NHS staff to deliver the programme

- created translated promotional materials and follow-up resources on the Padlet, an easily accessible online platform

Impact

Since June 2024, 16 courses have been delivered with 45 patients attending.

Among those completing feedback:

- 100% learned ‘a lot’ more about NHS maternity services

- 92% learned ‘a lot’ more about their rights

- 83% felt a large increase in confidence about giving birth

What people said

Romanian participant: “I found in this course a safe space where I could address all my questions and concerns.”

Tips for success

- Partnership working is vital to avoid duplication and share benefits.

- Co-produce with staff and service users to ensure content is culturally appropriate and accessible.

What next?

Plans include piloting in-person group sessions to tackle digital exclusion and expanding to other regions and languages.

Recommendations for national programme teams

Actions for the national programme teams

Leadership, quality and professional standards

The NHS will work towards strengthening standards of translation and interpreting services by improving market management.

This will include focusing on commercial frameworks for procurement and model contracts and working with framework hosts such as Crown Commercial Service (CCS) and NHS Shared Business Services (NHS SBS).

This will address, for example:

- mandatory minimum level 3 qualifications for interpreters and clear criteria for using highly skilled interpreters (level 6 or level 7) in critical situations (such as emergencies requiring informed consent)

- guidelines on the safe use of tools like AI and video interpreting by suppliers, including information governance considerations

- strategies to address funding, pay structures, and market sustainability, ensuring equitable access to qualified interpreters

Access and barriers to services

- Develop or signpost a set of priority translated communication messages for national clinical and prevention programmes (for example, on screening programmes).

- Produce communication messages translated into multiple languages to promote awareness of patients’ rights to access interpreting support.

- Develop clear, mandated guidance on the recording of patient language need in EPRs, across all care settings.

Equity, cultural sensitivity and rights

- Develop and run a communications campaign among the public, patients and staff to raise awareness of and promote access to interpreting support.

- Review mandatory training, including equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) training, to make sure staff understand patients’ rights to accessible language information and the importance of being culturally sensitive.

Digital opportunities and challenges

- Develop a national policy briefing with relevant stakeholders on the ethical and appropriate use of AI in healthcare for translation and interpreting services. These standards should:

- ensure clinical safety and accuracy of AI outputs, particularly for sensitive tasks like medication instructions

- provide clinical assurances and governance frameworks (including indemnity and responsibility) for AI use

- outline when AI tools are suitable and when alternative methods (for example, telephone interpreters) should be prioritised

- specify the appropriate and safe use of AI tools for translation and interpreting

- include recommendations for reliable AI tools, addressing known variances in accuracy for different languages

- emphasise patient safety and ensure staff only use approved tools

- address any information governance considerations, ensuring compliance with data protection laws

- Develop clear guidance across all care settings for recording patients’ language needs in electronic patient records.

Safety, confidentiality and consent

The National patient safety healthcare inequalities reduction framework sets out 5 principles to reduce patient safety healthcare inequalities across the NHS.

It outlines opportunities for implementation that local teams and ICBs can take up and the work NHS England is doing nationally to support this.

The principles align with the aims of NHS England’s patient safety strategy and the Core20PLUS5 approach (both for adults and for children and young people) to addressing healthcare inequalities.

National case study

Investigating the impact of language barriers in maternity – the recommendations which informed this framework for action.

Background

Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries – United Kingdom (MBRRACE-UK) is a national programme funded by the Care Quality Commission to review maternal and infant deaths.

In 2024, MBRRACE-UK published Saving Lives – Improving Mothers’ Care State of the Nation Report and a separate Perinatal Confidential Enquiry report, exploring the care of recent migrant women with language barriers specifically.

The challenge

The reports found that:

- inconsistent or missing assessment and documentation of language needs were common

- formal interpreter services were rarely used, and when they were, were not used consistently throughout care

- interpreter use was crucial for critical discussions, including surgical consent and ultrasound appointments

- late booking and missed antenatal appointments were frequent among women whose cases were reviewed, often due to financial constraints and digital exclusion

Maternal mortality is nearly 3 times higher for Black women, and nearly 2 times higher for Asian women compared to White women.

Women in the most deprived areas face double the risk of maternal and neonatal death.

Migrant women with limited English proficiency were particularly at risk, with only 4% receiving ‘good’ care.

In 73% of cases looked at by MBRRACE-UK, professional interpretation was not documented, and in 50%, no interpretation was used at all.

The approach

The reports outlined 6 national recommendations, including that the language needs of women and their requirement for a professional interpreter should be recorded in their digital maternity record to ensure consistency across NHS interactions, including emergencies.

Clinicians must ensure verbal information is understood and that women’s specific needs, such as language requirements, are accounted for in individualised care.

Tips for success

- Ensure flexibility in appointment lengths to accommodate communication needs.

- Guarantee access to formal interpreter services in all critical healthcare discussions.

- Proactively follow up on missed appointments and offer alternative engagement methods.

- Provide translated materials and verbal explanations to ensure comprehension.

- Raise awareness of healthcare entitlements, ensuring women know they have free access to GPs.

- Implement national training programs for healthcare staff on language barriers and communication strategies.

Acknowledgements

The guidance was developed by NHS England’s National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme in collaboration with NHS South Central and West Commissioning Support Unit and involved extensive engagement with patients with LEP, NHS staff and stakeholders, an evidence review and market analysis.

In addition:

- National Voices led user-research with 6 different language minority groups

- NHS Providers supported the engagement and research with provider trusts

- The Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Surrey provided research insights relating to the use of AI tools for multilingual communication

Resources

Key reports

- Community languages translation and interpreting service: research findings – NHS South Central and West Commissioning Support Unit

- Community languages, translation and interpreting services – National Voices

- Evidence review report on the use of AI in public services, with a focus on the NHS – Centre for Translation Studies, University of Surrey

- Lost for words: improving access to healthcare for ethnic minority communities – Healthwatch

- Ethnic inequalities in healthcare: a rapid evidence review – NHS Race and Health Observatory

- Clinical investigation booking systems failures: written communication in community languages – Health Services Safety Investigation Body (HSSIB)

- The care of recent migrant women with language barriers who have experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death – MBRRACE-UK

- Saving lives, improving mothers’ care – State of the Nation Report – MBRRACE-UK

Guidance, legislation and policy

- A national framework for NHS action on inclusion health

- Inclusive digital healthcare: a framework for NHS action on digital inclusion

- Guidance for Commissioners: Interpreting and Translation Services in Primary Care (updated 2019)

- Addressing health inequalities through engagement with people and communities

- Working in partnership with people and communities: statutory guidance (updated May 2023)

Data sources

- Language barrier population tool – NHS England

- Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Dashboard (FutureNHS; requires log-in)

- Health inequalities datasets – Office for National Statistics

Annex A: Impact of language barriers on access, experiences and outcomes

Language barriers can deepen existing health inequalities and the impacts often intersect with factors connected to age, ethnicity and social disadvantage.

For example, people aged 75 or over who have limited English proficiency are twice as likely to report ‘not good’ health compared to people in the same age group whose main language is English.

This significantly magnifies the effect seen across all age groups (see Evidence for change section)

Although language needs and ethnicity are not the same, people with limited English proficiency are frequently from ethnic minority communities.

The intersection between the two is complex and must be understood in relation to the specific experiences and contexts of different groups.

- Ethnic minority communities are more likely to experience multiple long-term health conditions – and experience them earlier in their lives than the majority white population.

- People with limited English proficiency are more likely to experience racism, migration stress, and complex trauma.

- Asylum seekers and refugees are more likely to experience poor mental health including higher rates of depression, post traumatic stress disorder and anxiety disorders.

- Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities report issues when attempting to register with a GP due to low literacy levels. They also report difficulty completing GP registration forms and a lack of help from professionals.

- Women in ethnic minority communities are more at risk from death in childbirth, with a nearly 3-fold difference in maternal mortality rates amongst women from Black ethnic backgrounds and an almost 2-fold difference amongst women from Asian ethnic backgrounds compared to white women.

Barriers when accessing healthcare

People who speak little or no English often face significant challenges when trying to access NHS services.

These include:

- difficulty accessing written healthcare information that meets language or literacy needs

- A 2024 survey undertaken by NHS South Central and West Commissioning Support Unit found that only 6% of NHS staff reported that sufficient written information in other languages was ‘always’ available

- inability to use the NHS App to book appointments or order prescriptions because it is only available in English

- digital exclusion, limiting their ability to access services online

- lack of awareness of professional interpreting services or difficulty accessing them – including interpreters who speak the right dialect

- concerns about translation and interpreting quality, including confidentiality, safety and cultural understanding, which can lead to missed or cancelled appointments

- limited awareness of their rights and eligibility to use interpreting and translation services

These barriers are mirrored by the experiences of NHS staff, who report:

- limited awareness of what translation and interpreting services are available and how to book them

- complex and inconsistent booking systems across departments

- inadequate and inconsistent processes for recording patient language needs

- lack of audit and feedback mechanisms to improve services

- lack of national standards or guidance to support them service improvement

As a result, people with LEP may avoid or disengage from healthcare altogether. This is reinforced by evidence that the NHS does not currently meet the full demand for translation and interpreting support.

An economic estimate by NHS South Central and West CSU found that the NHS spends around £75.5 million per year on these services.

This is far below the £250 to £300 million estimated to meet the needs of the wider population, based on current demographics and suggests significant unmet need.

Patient safety and quality of care

Language barriers are also a serious patient safety concern.

Between April 2022 and June 2022, 652,246 patient safety incidents were reported in England representing – an 8% increase compared to the previous year.

An estimated 237 million medication errors occur each year, leading to more than 1,700 deaths.

People with limited English proficiency are more vulnerable to medical harm and adverse events at various stages of care. Common risks include

- misinterpretation of symptoms – leading to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment.

- medication errors – through misunderstanding instructions on dosage, timing, and potential side effects

- lack of informed consent – patients may not fully understand procedures or risks

- non-compliance with treatment plans – due to unclear or misunderstood instructions

- delayed care-seeking – because of fear of communication issues or lack of interpreter availability

- increased stress and anxiety – from trying to navigate healthcare in a language they do not speak fluently

- lack of engagement with preventative and screening services – delaying access to timely care and contributing to poor chronic disease management

The frequent reliance on AI translation apps and informal interpreters such as family and friends to ‘get by’ increases the risk of medical errors.

These methods are unreliable and may result in key medical information not being interpreted or communicated accurately, with clinicians unable to get assurance that their advice is being received.

For example, in 2023 the BBC reported that the NHS’s failure to provide high-quality interpreting services had been a contributing factor in the deaths of at least 80 babies.

There are also safeguarding concerns when patients are unable to disclose abuse or provide sensitive information because a family member is acting as an interpreter.

These issues have been highlighted in multiple Healthcare Safety Investigation reports and by a Care Quality Commission report in 2024, which identified failure to provide effective communication in other languages as a cause of serious harm.

Publication reference: PRN01750