Introduction

Inclusion health is an umbrella term used to describe people who are socially excluded, who typically experience multiple interacting risk factors for poor health, such as stigma, discrimination, poverty, violence, and complex trauma.

People in inclusion health groups tend to have poor experiences of healthcare services because of barriers created by service design. These negative experiences can lead to people in inclusion health groups avoiding future contact with NHS services and being least likely to receive healthcare despite have high needs. This can result in significantly poorer health outcomes and earlier death among people in inclusion health groups compared with the general population.

Extremely poor health status among inclusion health groups is driven by severe disadvantage and clusters of social risk experienced when people are socially excluded. For example, someone who is alcohol dependent may also be homeless resulting in vulnerability, limited opportunities, extremely poor health and a reduced life expectancy. Risks may also build up over the life course. For example, adverse experiences in childhood may be associated with social exclusion, vulnerabilities and health needs both in childhood and later in life.

Inclusion health groups therefore require an explicit, tangible focus in system efforts to reduce healthcare inequalities.

What is meant by inclusion health?

People in inclusion health groups include:

- People who experience homelessness

- People with drug and alcohol dependence

- Vulnerable migrants and refugees

- Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller communities

- People in contact with the justice system

- Victims of modern slavery

- Sex workers

- Other marginalised groups

People who are socially excluded are likely to have the following experiences in common:

- Discrimination and stigma

- Violence and the experience of trauma

- Poverty

- Invisibility in health datasets

Which result in:

- Insecure and inadequate housing

- Very poor access to healthcare services due to service design

- Poor experience of public services

- Poorer health than people in other socially disadvantaged groups.

Our vision for reducing healthcare inequalities is to provide exceptional quality healthcare for all, through equitable access, excellent experience, and optimal outcomes.

This framework focuses on the role that the NHS plays in improving healthcare, and how partnerships across sectors such as housing and the voluntary and community sector play a key role in addressing wider determinants of health.

The framework is based on five principles for action on inclusion health (Figure 1). It is focused on actions to address issues which are common across inclusion health groups. Useful resources are listed at the end to inform more detailed planning.

Figure 1: Principles for action on inclusion health

Inclusion health principles

1. Commit to action on inclusion health

2. Understand the characteristics and needs of people in inclusion health groups

3. Develop the workforce for inclusion health

4. Deliver integrated and accessible services for inclusion health

5. Demonstrate impact and improvement through action on inclusion health

This framework has been developed by NHS England in collaboration with a wide range of partners such as the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations. NHS England ran several workshops with people with lived experience of inclusion health to understand challenges that individuals face. Learnings from their experience highlighted the urgent need to improve inclusion health now and form an important part of this framework.

Policy context

Reducing health inequalities is an NHS England priority. Delivering effective services that address the issues faced by inclusion health groups is an important contribution to this ambition, seeking sustained action that responds to the needs that vary across inclusion health groups. This action is key to achieving the government ambition to improve healthy life expectancy by 2035 while narrowing the gap between areas where life expectancy is highest and lowest.

NHS England has set out five strategic priorities for reducing healthcare inequalities and the Core20PLUS5 approach for adults and for children and young people to give a practical focus for action. Core20PLUS5 sets out the population focus (the Core20PLUS), as well as clinical areas for action on healthcare inequalities. The ‘Core20’ population is the most deprived 20% of areas of England as defined by the Index of Multiple Deprivation, while PLUS groups are other groups who may experience poorer than average access to, experiences of, or outcomes from NHS services. Inclusion health groups are therefore a priority group, and we are calling for all parts of the system to drive efforts to improve healthcare provision for this group in our ambition to reduce health inequalities.

NHS England and integrated care boards (ICBs) have a legal duty to have regard to reducing inequalities associated with access to and outcomes from NHS services. ICBs have statutory duties to support partnership working, where this would help to tackle inequalities. A focus on responding to inclusion health groups will be crucial for fulfilling these duties.

This framework is intended to help every integrated care system to shape and take their next steps in improving access, experience, and outcomes for people in inclusion health groups, recognising that systems will be at different stages in this journey.

NHS leaders at all levels of the system will need to act on this agenda with their partners. The multiple interacting causes of social exclusion and ill health in inclusion health groups require cross-sector, interagency working within integrated care systems (ICSs), and responses will need to be shaped through coproduction with people with lived experience.

The Long-Term Plan and Long-Term Workforce Plan made commitments to increase the role of the NHS as an anchor organisation. There are many examples of how NHS anchor organisations are supporting inclusion health groups, and other communities that experience inequalities. The Health Anchors Learning Network provides resources and learning opportunities to support organisations to influence the health and wellbeing in communities.

The case for action

Inclusion health groups are relatively small but significant populations with high needs for healthcare, but who face a range of barriers in accessing healthcare services.

Whilst numbers may be small, the cost is high to individuals and systems. By taking a strategic systems approach to inclusion health systems think about how to better utilise resources and work with partners to develop approaches that reduce pressure on the system, save lives and improve health life expectancy.

Extremely poor health outcomes

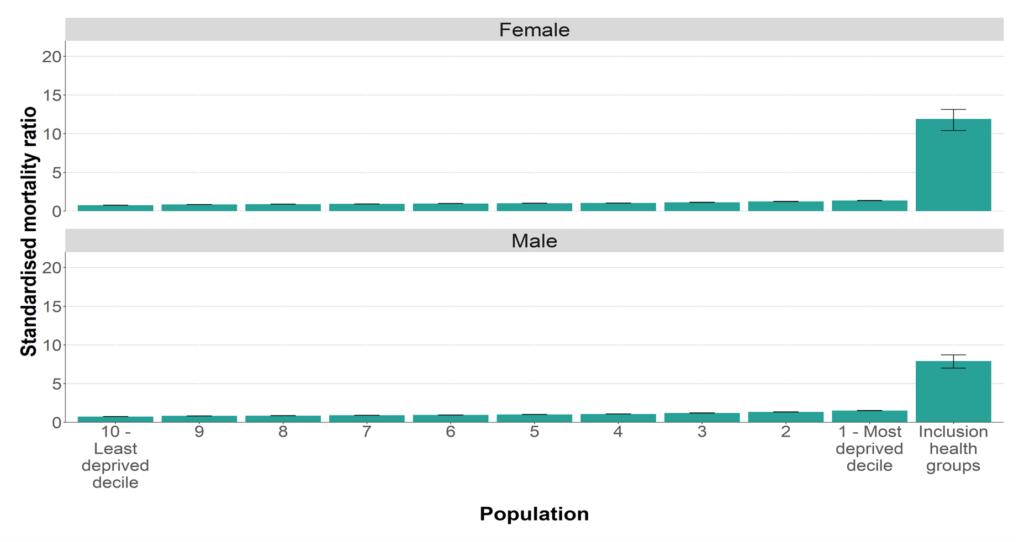

People in inclusion health groups experience a range of poor health outcomes. In particular, people inclusion health groups tend to die earlier than the general population. Figure 2 illustrates that the relative mortality of people in inclusion health groups far exceeds that of people from the most deprived communities of England – the inequality of outcomes among inclusion groups is extreme.

Figure 2: Standardised all-cause mortality ratio for inclusion health groups, compared to the general population by deprivation decile.

Source: Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (2022).

People in inclusion health groups are also more likely to experience range of morbidities particularly mental health problems and substance dependence, and often have untreated long-term conditions. The children of parents in inclusion health groups are more likely to have poor health across their life-course because of their extremely disadvantaged start in life. There is a risk that disadvantages in socially excluded groups flow from generation to generation – from parent, to child, to grandchildren. Appendix A includes selected statistics on the health of inclusion health groups.

Barriers to accessing health services

Discrimination and stigmatisation

Many individuals report negative experiences when using services often relating to the attitudes of staff. They highlight that discrimination and stigmatisation discourage them from engaging with services. For example:

- Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities report difficulties in registering with a GP because of a lack of cultural awareness and a perception that they will be ‘expensive patients’. GPs may also be reluctant to visit sites.

- People who have been in contact with the criminal justice system avoid contact with the NHS because of distrust linked to previous negative experiences of statutory services such as the care system.

- Sex workers do not attend cervical screening and antenatal appointments because of fear of discrimination, stigmatisation and criminalisation among other factors.

Logistical challenges and service design

In many cases there is evidence that inclusion health groups are excluded or discouraged from using health services due to unnecessary logistical challenges or badly designed services. For example:

- Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities report issues when attempting to register with a GP due to low literacy levels. They also report difficulty completing GP registration forms and a lack of support from professionals to help.

- Vulnerable migrants report limited access to translation services, which greatly impacts their capacity and confidence to engage with care and support.

- Sex workers cite opening hours and the location of services as a barrier to accessing routine health checks, cervical screening and antenatal checks.

Invisibility in health datasets

Inclusion health groups are not consistently recorded in electronic health datasets when interacting with health services. This means they are effectively invisible in data used for service design and evaluation, and so services do not meet their needs.

Digital exclusion

Digital technologies present a key opportunity to overcome many communication and logistical barriers to accessing services. This may include presenting information in short films and pictures, using online tools to translate to different languages and providing remote access to services at times that suit. As there can be high rates of digital exclusion among inclusion health groups, digital technologies can present some challenges, and will need to be properly considered. For example, 90% of people experiencing homelessness own mobile phones rather than laptops or home computers, which means that they access the internet with technology that is less reliable. This is due to issues such as cost of mobile devices and data, theft, poorer network coverage and comparatively lower data access. The NHS Digital Inclusion Framework provides more information on how to take action in this area.

Lack of empowerment

The complex structural barriers created by social exclusion and negative experiences of using public services can make it difficult for people to look after their health and wellbeing. Personalised care and peer support are key to understanding what matters to the person and empowering them to have greater choice and control over their health and the way their care is delivered. For instance, a recent study highlighted that a lack of peer support in the self-management of long-term conditions.is an issue for people experiencing homelessness and rough sleeping. Strategic coproduction and asset-based approaches are important ways to empower people and communities and use their strengths to improve healthcare.

Benefits of improved pathways

Without good access to primary and community care, and early or preventative interventions, people in inclusion health groups are likely to turn to acute services. For example, A&E attendance is 6-8 times higher for people experiencing homelessness and 28 times higher for people who experience both homelessness and rough sleeping and alcohol dependency.

There is evidence that implementing solutions for inclusion health, such as improved health and social care pathways and providing accessible effective services, benefits patients and reduces the costs of health and social care services.

A study undertaken in 2022 investigating the cost-effectiveness of three different ‘in patient care coordination and discharge planning’ configurations for adults experiencing homelessness, highlighted that specialist Homeless Hospital Discharge (HHD) care is more cost-effective than standard care.

Cost effective analysis shows that patients accessing HHD care use fewer bed days per year (including both planned and unplanned readmissions) and presented better quality-adjusted life year (QALY) outcomes. In addition, patients using specialist care have more planned readmissions to hospital and, overall, use more NHS resources than those who use standard care.

Furthermore, a recent cost-benefit analysis based on current experiences of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller families showed that an improved Dementia and Carer stress or depression pathway was estimated at less than half the cost of the current pathway, from £20,298 down to £8,884. The analysis also highlighted that up-front investment, for example in appropriate social work engagement, or in GP outreach work, can pay for itself many times over in the longer term.

Some areas have introduced High Intensity Use (HIU) Services to proactively meet the needs of the most frequent attenders of the local A&E, a significant portion of whom belong to inclusion health groups helping to address health inequalities faced by this cohort while alleviating pressure on urgent and emergency care pathway.

Research has shown a clear link between high intensity use of emergency services and wider inequalities. There is a correlation between the poorest parts of the country and those with the highest concentration of individuals attending A&E frequently. High intensity users are thought to equate to almost a third (29%) of all ambulance arrivals at A&E, and one in four (26%) emergency admissions. HIU services help to free up frontline resources and reduce costs, while improving care for cohorts that face challenges with accessing healthcare and wider support from public services in the community.

The cost of doing nothing

Failing to address inclusion health costs the NHS and society at large. For example,

- Meeting the needs of people in severe and multiple disadvantaged groups costs society an estimated £10.1 billion per year.

- Prior to COVID-19, health inequalities were estimated to cost the NHS an extra £4.8 billion a year

- The frequency of unplanned emergency care has a significant impact on the health system, putting greater strain on the service and costing the NHS £2.5 billion a year.

Further costs are also associated with delays in discharge due to the complications in securing out of hospital care, particularly for those who have no home to return to. Inclusion health groups make up a large part of delayed discharge costs.

- In 2022/2023, delayed discharge cost the NHS £1.89bn.

- In December 2022, more than 13,000, out of a total of 100,000 hospital beds in England were occupied by patients who were medically fit for discharge.

Once discharged, people in inclusion health groups are more likely to be readmitted due to difficulties in maintaining their health while recovering.

Roles and responsibilities

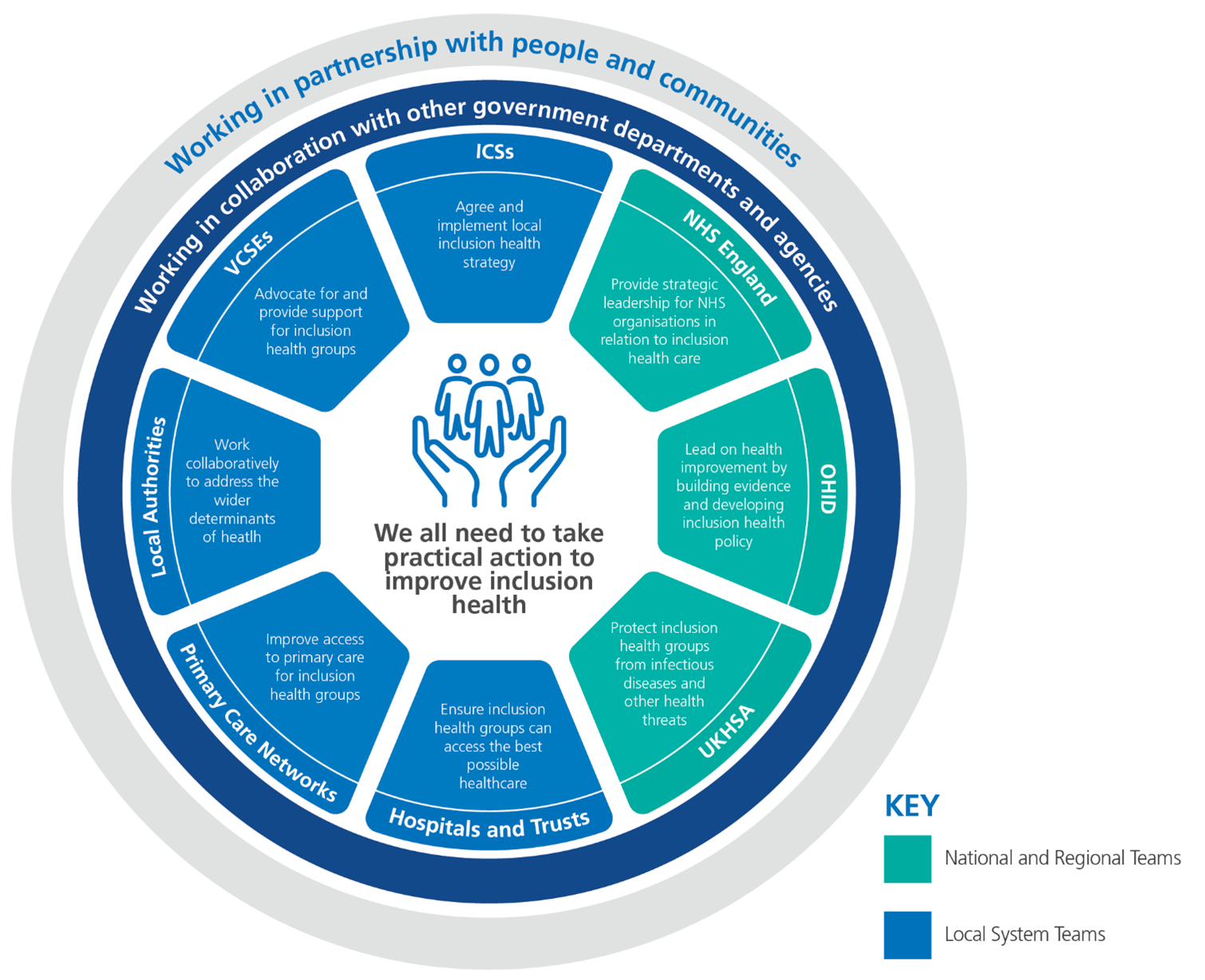

Everyone needs to take practical action to improve outcomes for inclusion health groups to address systemic health inequalities they face. To do this, we need an understanding of the issues people face, and to develop knowledge, skills and confidence alongside partners to help and deliver change.

Figure 3 illustrates the roles of different partners who can work together to develop personalised integrated support for people in inclusion health groups. It is not exhaustive and, depending on local circumstances, different stakeholders may be involved. Appendix B has further information on roles of different partners.

Figure 3: An overview of roles and responsibilities in relation to inclusion health.

Principles for action

This section sets out principles for practical action and high impact changes that can be made now to improve access and outcomes for inclusion health groups, recognising that long-term cross sector changes to policy and services are needed to tackle the extreme burden of disease and poor quality of life experienced by people in inclusion health groups.

The principles were developed following a review of available best-evidence on inclusion health and listening to people with lived experience and key stakeholders. Stakeholders included people with lived experience, VCSE organisations, ICSs, OHID, the UKHSA. national and regional teams and the Inclusion Health Network for seven ICSs, supported by Pathway, Groundswell and the Kings Fund

The principles are intended to guide the design and delivery of inclusion health strategy and services nationally, regionally and locally, providing guidance for NHS organisation and other partners working collaboratively as part of integrated care systems. Within each principle, we have identified useful actions, explained what good looks like, highlighted practical action, and provided a case study to illustrate effective working.

Figure 4: Principles for action on inclusion

|

1 |

Commit to action on inclusion health |

Ensure the ICB has a named lead for inclusion health to ensure ICP strategies and ICB plans tackle inequalities of access, experience and outcomes for people in inclusion health groups. |

|

2 |

Understand the characteristics and needs of people in inclusion health groups |

Proactively improve data and insights on the needs of people in inclusion health in your population. Use this to drive improvement. |

|

3 |

Develop the workforce for inclusion health |

Develop the workforce so all staff understand inclusion health and trauma-informed practice. Develop specialists in inclusion. Support employment of people in inclusion groups as NHS anchor organisations. |

|

4 |

Deliver integrated and accessible services for inclusion health |

Use best practice to commission sufficient specialist services for inclusion health groups. Raise the quality of all services to ensure equitable access, experience and outcomes for all |

|

5 |

Demonstrate impact and improvement through action on inclusion health |

Evaluate the impact of changes made. Ensure people with lived experience inform improvement and evaluation. |

Principle 1: Commit to action on inclusion health

The voices of socially excluded members of our communities are often left unheard, and their needs invisible. To serve their communities inclusively, senior leaders need to advocate for inclusion health at every level and enable all voices to be heard. This requires commitment and action from the very top with leaders spending time in their community, and seeing first-hand the challenges people are experiencing. Senior leaders will need to balance operational pressures with a focus on providing equitable services for all members of their community.

Good looks like

There is a named clinical lead on the ICB with clear responsibility for inclusion health who provides direction and advocates to ensure that meaningful actions are set out in key strategies and plans. This will ensure that:

- Senior leaders commit to hearing and responding to the voices of people with lived experience and spend time within their communities to understand their needs.

- Strong cross sector strategic partnerships are established between NHS bodies, local authorities, VCSE organisations and wider partners with commitment to developing and implementing integrated approaches and services for people in inclusion health groups. For example, West Yorkshire ICB are in the process of setting up an Inclusion Health Unit to lead and drive forward progress. The unit will include members from across the system to progress collective priorities, share best practice, learning, resources, and deliver effective change on inclusion health across the ICB footprint.

Suggested practical actions

- Identify a named senior responsible officer at ICB level who has responsibility for championing, challenging and driving action on health inequalities and inclusion health.

- Identify a named senior responsible officer for health inequalities and inclusion health in each partner organisation within the ICS.

- Report on progress delivering inclusion health activity at board level and provide opportunities for board members to spend time with people in inclusion health groups and understand their needs.

- Use the VCSE Inclusion Health Audit Tool to understand how effectively your organisation is engaging with service users and trusted community partners.

- Document how engagement with people with lived experience has informed service delivery and ensure this information is made publicly available.

- Build leadership for inclusion health into leadership programmes.

- Use communication strategies to raise awareness of the needs of people in inclusion health groups and what good looks like.

Example of good practice

Embedding inclusion health as a priority across North Central LondonNorth Central London ICB has successfully embedded inclusion health as a priority for action across its system. This has been achieved through a clear and visible commitment from the top, with senior leaders championing the issue across the Integrated Care Partnership (system) and Borough Partnerships (place).

Inclusion health has been highlighted as a key component of the North Central London Population Health and Integration Strategy, as well as one of its locally nominated PLUS groups from the Core20PLUS5 framework.

The agenda is underpinned and driven by a strong strategic partnership, involving close working with the Directors of Public Health, housing, health, social care and VCSE organisations across the areas five Boroughs.

Senior leaders also place strong emphasis on the importance of listening and hearing the views of those with lived experience to understand the complexity of their needs and challenges they face.

A key piece of work that supports this approach has been the development of an Inclusion Health Needs Assessment to help the partnership better understand the demographics, health needs, experiences and service provision for inclusion health groups.

As part of the assessment, an extensive engagement exercise was undertaken with people with lived experience, as well as capturing the experiences of staff and views of senior system stakeholders. This allowed the ICB to gain a broad strategic overview on inclusion health across the system, leading to improved cross-borough equity of provision, establishment of a Homeless Health and Care Community of Practice, and further participation opportunities involving those with lived experience.

Other successful projects across the ICB include the development of outreach healthcare services for people experiencing homelessness in Islington, Barnet, Camden, Enfield and Haringey (integrated), and RESPOND, an integrated asylum-seeker and refugee health service which has helped more than 1400 asylum seekers with their physical and mental health.

Example of good practice

The South West Migrant Health NetworkThe South West Migrant Health Network was developed to unite key partners and communities to improve the health and wellbeing of migrants across the region.

Central to its success was members’ commitment to place those with lived experience at the core of the network, alongside other professionals from the NHS, OHID, public health, local authorities and the third sector. This enabled the network to hear first-hand the barriers that migrants experience and set a collaborative tone, working with all partners to make positive change a reality.

Input from all members has resulted in the creation of a one-stop online hub housing evidence-based resources, equipping professionals with the tools and information they need to meet migrant’s specific health needs.

By engaging effectively with service users and trusted community partners, the network has also seen positive change, including:

- Improved oral health and dentistry provision for asylum seekers living in contingency accommodations.

- The sharing of multilingual resources for vaccination, immunology guidelines and the guide to the NHS, including Arabic (for the Syrian re-settlement programme), Chinese (for the Hong Kong programme), Farsi (for Afghan refugees) and most recently Russian and Ukrainian (for those fleeing Ukraine).

- The sharing of resources and examples of good practice for delivering Making Every Contact Count (MECC) interventions for asylum seekers and resettled communities both in asylum seeker accommodation and community-based health clinics.

- Research, practice and policy collaborations being nurtured, and examples included in research funding bids (for example a successful bid to the National Institute for Health and Care Research under the Health and Social Care Delivery research awards has enabled the co-design of a peer-led community approach to support mental health in refugees.

- The creation of a Future NHS workspace, where a wealth of resources to support migrant health are available.

Principle 2: Understand the characteristics and needs of people in inclusion health groups

Information about people in inclusion health groups is often not recorded in traditional data sources. This means that their needs are often overlooked, and their voices are seldom heard. Assessing the needs of our entire communities requires us to look beyond routinely available data and work creatively with all residents and groups to seek wider sources of information. NHS organisations doing this well will balance the use of information held in traditional data sources with the qualitative insights from trusted community partners. They will work with people experiencing social exclusion to understand and prioritise problems from their perspective.

Good looks like

There is a robust health needs assessment for inclusion health which informs the actions of the ICS. This requires:

- Taking a co-ordinated and consistent approach to understanding the needs of inclusion health groups.

- Using current data on deprivation, inclusion health, learning disabilities, severe mental illness, substance misuse and proxy measures for social exclusion

- Working with trusted community partners who hold a wealth of information about your population, as well as Local Authority public health teams and analysts.

- Listening to the voices of people with lived experience.

Suggested practical actions

- Ensure that place based plans and joint strategic needs assessments reflect the needs of the people in your communities living in inclusion health groups. This should inform the actions of the ICS.

- Work collaboratively with wider system partners to use Public Health Outcomes Framework (PHOF) indicators, such as homelessness indicators, school readiness and drug misuse indicators, to build an understanding of local needs.

- Improve methods of collecting routine data by using the Fingertips tool, SPOTLIGHT tool and health inequalities dashboard to build the inclusion health data profile in your area.

- Work with your data and Populations Health Management (PHM) experts to draw on all available information to inform service provision. The Population Health Management Academy available via Future NHS provides a forum for information, discussion, news and the sharing of best practice for health, social care, public health and voluntary sector colleagues who want to collaborate and innovate to drive personalised approaches to care interventions.

- Develop a research approach with trusted community and academic partners to draw on rich qualitative measures.

- Use participative research approaches to support people with lived experience contribute to research and evidence.

Example of good practice

Looking beyond data to find effective solutions to reduce inequalities in cancer screening

In response to poor uptake rates of cancer screening services among some inclusion health communities in Charnwood, Leicestershire County Council worked with Charnwood local community groups, people with lived experience, primary care and the local GP Network to discover insight driven solutions.

The partnership recognised early on that traditional data sources would fall short of offering the answers, and that to fully understand the barriers to attending screening, they would need to engage with those with lived experience.

Working closely with trusted community groups, they ran six focus groups involving participants from Bangladeshi and Polish communities, Gypsy Roma Travellers, as well as carers and those experiencing homelessness and rough sleeping.

Alongside this, a data analysis was undertaken to look at variations in screening uptake by GP practice and Primary Care Network. The research focused on cervical, breast and bowel screening.

The research highlighted barriers as: Lack of knowledge and misinformation, influence of family history, language and technology challenges, access to GPs and lack of transparency in care provided, the intimate nature of screening and fear of the unknown, cultural issues, and not taking into account wider issues such as mental health and health literacy.

The findings enabled a number of recommendations to be made, including: building trust and rapport with the local community, enhancing access to healthcare and improving knowledge and awareness using trusted sources in the community.

Beacon and Carillon Primary Care Networks have already implemented a number of the recommendations by:

- Offering Saturday appointments via the extended access service.

- Running a multidisciplinary outreach clinic pilot as an opportunity to provide holistic care to patients in the community.

- Collecting data on patients that have declined bowel cancer screening to help understand the barriers to attending.

- Running a bowel cancer screening audit to explore the outcomes and effectiveness of telephone call interventions.

Example of good practice

Delivering health services to Gypsy, Roma, Traveller and Showmen communities in ThurrockRecognising the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on the Gypsy, Roma, Traveller and Showmen (GRTS) communities, the Public Health team at Thurrock Council worked with partners to enhance vaccination and testing outreach services to this group.

Whilst onsite, the Traveller Liaison team gained valuable feedback from site residents on their most pressing health concerns. Diabetes, medication management, immunisations, mental health, substance misuse and long covid were all highlighted as important issues.

Following this feedback, the team successfully secured funding from the ICB Health Inequalities programme and extended the outreach work further to encompass all of the health concerns raised by site residents. This has resulted in a programme of thirty events between September 2022 and February 2024 across five site locations.

Between January and July 2023, 202 residents have been seen by health services onsite, with 16 new GP registrations and 24 onward referrals to other services.

Traveller Liaison Officers report that each time they visit, communities are generally positive and are more trusting about health colleagues coming onto site. Face-to-face engagement has opened up a valuable feedback channel with members of the GRTS community highlighting the best time of year to visit, as well as key periods to avoid (e.g., when there are fairs, and the Showmen work away). This has assisted the planning of future events and evaluation/learnings from past events where uptake had been lower than expected.

Organisations involved have included Thurrock Council, Thurrock CVS, Midlands Partnership Foundation Trust, Essex Partnership University Foundation Trust, North East London Foundation Trust, Thurrock and Brentwood MIND, Mid and South Essex Integrated Care Board, Provide, Healthy Living Pharmacy Ltd, a number of specific GP practices and the Showmen’s Mental Health Awareness Trust.Principle 3: Develop the workforce for inclusion health

The workforce is a key enabler in improving healthcare access, experience, and outcomes. It is important that all staff understand how to support people well. This includes delivering personalised care, allowing for extra time and support, and treating people with dignity and empathy. People from inclusion health groups are entitled to use NHS services but too often they are turned away when seeking care.

Having plans in place to ensure staff are up to date with training around entitlement to care, inclusion health and trauma-informed approaches will help address this. Using levers such as ICB workforce strategies and the NHS’s position as an anchor organisation can ensure we have an inclusive workforce fit to support people in inclusion health groups.

Good looks like

Ensuring that training on inclusion health is mandatory for every worker. This will lead to:

- Everyone (policy makers, commissioners, providers, and front-line staff) understanding what inclusion health is, and the impact on access, outcomes and experience.

- Frontline staff having the skills needed to work with inclusion health groups, such as compassionate care which is culturally competent and responsive to relational injury and trauma.

- Ensuring inclusion health is included in workforce development strategies and plans.

Suggested practical actions

- Ensure training on inclusion health is accessible to all staff (see Figure 6 for more details).

- Provide opportunities for leaders and specialist staff to develop expertise in meeting the needs of inclusion health groups.

- Share best practice and learning across the system at national, regional, and local levels.

- Offer paid and voluntary employment opportunities to people from inclusion health groups.

Figure 6: Training on inclusion health

Training for staff on inclusion health covers:

- What inclusion health is and how to address health inequalities?

- How to develop and deliver culturally appropriate, compassionate, trauma -informed care.

- Digital inclusion and health literacy

- Understanding people’s entitlement to services and feeling confident to support and refer individuals appropriately,

- Understanding where to access information to support people from inclusion health groups,

- How to use Personalised Care to enable people to have greater choice and control over their care and support, address wider determinants of health.

- How the ‘Making every contact count’ (MECC) approach, can be adapted for inclusion health groups to encourage conversations about health at scale.

Useful training resources include:

Example of good practice

South East workforce development programme developed to improve the healthcare of those experiencing homelessness.Key partners, including the regional teams of the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, Workforce Training & Education NHSE, and universities in Southampton, Surrey and Canterbury and Oxford, worked together to develop the Homelessness Workforce Development programme across the South East.

The programme was created to equip the health and social care workforce in the region with the right skills and training to improve health and mental health care for those experiencing homelessness.

The programme offered:

- Clinical psychology training placements in non-NHS homelessness practice settings.

- Certificated homelessness psychosocial intervention education delivery.

- The homelessness community of practice – a network of continued learning and development.

- Homelessness practice peer support worker training.

The work resulted in:

- A number of Clinical Psychology (CP) training placements established from the training programmes in Southampton, Surrey, Canterbury and Oxford. 60% of trainees said they were highly likely to work in the homelessness sector post qualification, and 80% said they gained a greater understanding of inequalities that was broader than healthcare inequalities.

- The development of a suite of programmes including a Postgraduate Certificate, Diploma and MSc and Undergraduate Certificate in Psychologically Informed Homelessness Practice at the University of Southampton. The course is open to front line workers within homelessness settings. A continued professional development pilot launches in September 2023 with the main programmes scheduled for September 2024.

- The establishment of a homelessness community of practice. Launched in July 2022, the network runs regular webinars, meetings, research events, an annual conference and an online resource to provide opportunities for continued learning.

- More peer support workers within voluntary sector organisations being trained to support rough sleepers and those experiencing homelessness. Peer supervision training and wrap around support is available for organisations to build sustainability.

Example of good practice

Access to employment programme pilot – supporting those with lived experience of homelessness into work.

In April 2021, NHS England and Improvement worked with Pathway, Groundswell, the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), and the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) to launch the Access to Employment programme pilot.

The programme was set up to support people with lived experience of homelessness to secure employment into Health Care Support Workers (HCSW) roles.

In doing so, the programme also aimed to:

- Seek to understand and address barriers to employment amongst those with lived experience of homelessness.

- Develop and deliver a tailored coaching programme, equipping participants with the skills to submit job applications, undertake successful interviews, and secure job offers at Trust level.

The pilot resulted in five pre-employment events, one in each of the Trust catchment areas, attracting a total of 22 individuals with lived experience.

Conversation rates were high with almost half of participants who attended the events receiving job offers. In three Trusts, almost all participants were interviewed and offered jobs. Those not offered jobs were signposted to other opportunities and provided with further support to secure employment.

Other benefits of the work included raising homelessness as a key issue to Trusts, adding strength to Trust rhetoric about the importance of workforce inclusion and community engagement, and creating and rolling out new valuable entry roles into the workforce.

Principle 4: Deliver integrated and accessible services for inclusion health

Poor access to health and care services and negative experiences are commonplace for people in inclusion health, often related to the way healthcare services are commissioned and delivered. Although there are pockets of excellence, sustainable and widespread best practice requires NHS services reduce unwarranted variation across systems and partnering with the voluntary and community sector and other agencies to address issues. This means finding the right balance between making mainstream services accessible to all as well as providing specialist provision for excluded groups. These principles are key for all NHS services – not just specialist services – to ensure that people are not turned away from seeking care.

We often hear from people with lived experience that our services are inaccessible and fragmented, for example first hand insights through a programme of work on Core20PLUS5 for people in contact in people with the criminal justice system. Best practice requires joined up, personalised care with a focus on what matters to the individual and their needs. This may require access to a dedicated individual who can advocate for and support the user on their journey throughout the system.

As people from inclusion health groups can be vulnerable, healthcare staff will need to be familiar with referral routes and safeguarding services.

Good looks like

Developing clear and achievable goals and monitoring the ICS performance against these. This means:

- Understanding the gap between inclusion health needs across the system and what is currently spent (this could include health inequalities, specialist services and generic primary, community acute and specialist services)

- Commissioning specialist services (such as outreach provision for excluded groups) that reflect best practice

- Making generic services more accessible.

- Co-designing and delivering services with people in inclusion health groups in response to local needs.

- Working across organisations with both VCSE and wider partners to fund and sustain provision for inclusion health.

- Ensuring that safeguarding is an inherent part of all service design and delivery.

Suggested practical actions

- Work with system partners to implement the NICE Guidelines on Integrated health and care for people experiencing homelessness. General principles from this guidance could be applied to all inclusion groups.

- Use tools such as the Health Equity Assessment Tool (HEAT) and the Safe Surgeries Toolkit to consider health inequalities when designing and reviewing services. Further tools can be found in the reference section.

- Set up mechanisms for co-designing services with people and communities, such as strategic co-production

- Develop integrated multidisciplinary teams which deliver proactive coordinated care which meet the needs of people in inclusion health groups as outlined in the Fuller Stocktake Report.

- Ensure that roles such as healthcare navigators, care coordinators and social prescribing link workers are available to support people through the system.

- Recognise that general health service provision may not meet the needs of inclusion health groups and that specialist outreach services will need to be commissioned to address this.

- Identify a named lead for inclusion health on Safeguarding Adults Boards.

- Where a person in contact with NHS services is homeless or at risk of homelessness, ensure public sector duty to refer guidance is followed.

Example of good practice

RECONNECT North East: working in partnership to reduce reoffending and improve outcomes for prison-leavers.RECONNECT is a service led by the Reconnected to Health Partnership which consists of four organisations: Spectrum Community Health Community Interest Company, Rethink Mental Illness, Tees Esk and Wear Valley (TEWV) NHS Foundation Trust and Humankind.

The partnership recognised that effective support for people released from prison who have health and wellbeing needs is crucial for a positive re-entry into the community.

Often, lack of preparation and inadequate assistance can lead to ex-offenders experiencing difficulties engaging with health services in the community, a higher chance of partaking in dangerous health and a higher risk of reoffending.

To tackle this issue, the partnership developed RECONNECT, a service designed to help those released from prison to make links with important services such as GP practices, mental health services, drug and alcohol services and probation.

The service offers a person-centred friendly approach with Care Navigators providing 1:1 support to understand an individual’s health needs and any concerns before and after release.

In addition, those who use the service can benefit from financial and practical support and have an opportunity to become RECONNECT volunteers, helping others to transition back into the community in a positive successful way.

- Since 2019, RECONNECT has supported 1,292 prison-leavers across the North East.

- Referrals into the service soared 176% between 2020 and 2022, from 276 to 488 per year.

- In 2021, RECONNECT was granted £150,000 of additional funding to develop a new community hub for prison-leavers in Durham.

- ·In 2023, RECONNECT achieved the gold standard of the NHS Lived Experience Charter for its work improving opportunities for staff with lived experience of the care or justice system.

- The North East is now the top-performing region for wellbeing outcomes in prisoners with drug or alcohol issues – 59% of prison-leavers successfully engage with services within three weeks, compared to only 34% nationally.

Example of good practice

Palliative care for people experiencing homelessness in Liverpool.Brownlow Health – a large city centre GP practice in Liverpool, recognised that too often people experiencing homelessness in their community were not receiving sufficient palliative care.

To help address this issue, the practice partnered with Marie Curie Hospice in Liverpool to establish a specialist homeless palliative care service.

Funding was secured for a palliative care nurse and a homeless palliative care multi-disciplinary team was set up with a focus on the early identification of people with deteriorating health.

Outreach work enables the team to review and manage individuals at the end of their life, in an appropriate setting for them. The team works closely with the individual and hostel teams to enable a dignified death in a place of choice that feels like home, often the hostel that they have been staying in. The team are able to administer pain relief at the hostel, enabling planned deaths when requested rather than an individual spending their last days in a hospital.

The team work closely with hostel staff to give them the knowledge and skills needed to support individuals at the end of their life. They also offer emotional and spiritual support to staff once an individual has died.

The service has resulted in:

- An increase in the patients receiving end of life discussions and advanced care planning from 19% to 85%.

- A rise in patients receiving a medical palliative care review prior to death i from 13% to 90%.

- Growth in patients on the practice palliative register, increasing from 31% to 90%.

Feedback from the district nursing team has been positive:

“This is a superb example of services working together, supporting each other to get the best outcome for someone in a difficult situation. Your involvement has been an inspiration to our team.”

Principle 5: Demonstrate impact and improvement through action on inclusion health

Effectively evaluating inclusion health services is critical for ensuring that everyone in our communities receives the support and care they need. This can be a complex task requiring more creative methods due to significant limitations in access to quantitative data because inclusion health groups are not consistently recorded in electronic health databases. People in inclusion groups are also less likely to use formal complaints routes due to their experiences of relational injury, and far less likely to have family members advocating for them so their voices remain unheard.

Organisations making progress in this area use a mix of both established and new data collection and qualitative sources to give them the best understanding of how effective (or not) their services are. Co-designing evaluation approaches with relevant stakeholders including trusted community and VCSE partners, clinicians, and people with lived experience is central to supporting this approach.

Good looks like

Identifying clear and achievable targets on inclusion health and monitoring the ICS’s performance against these. This includes:

- Embedding evaluation into your everyday work.

- Including people with lived experience in your evaluation.

- Giving words and stories equal weight to numbers.

- Using inclusive language – finding out what language and terminology makes sense to the people involved and using it.

- Communicating your learnings to others – enabling stakeholders to act themselves.

Suggested practical actions

- Refer to ESS principles for good evaluation.

- Set clear achievable outcomes (differences or changes you hope to make) and indicators (what you need to measure to see if you are achieving your outcomes).

- Develop a logic model to set out the steps to reach your outcome. The VCSE Inclusion Health Audit Toolis a useful benchmarking resource.

- Seek to collaborate with academic institutions such as universities to develop research and evaluate services. It is an NHS duty for all ICSs to include research strategy in their Joint Forward Plan.

- Work with your Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) and complaints teams, who will have the skills needed to work with inclusion health groups and encourage feedback. Ensure that this information is fed into service improvement plans.

- Listen to VCSE organisations working with people in inclusion health groups. People in these groups often do not use formal routes to complain so it is important to listen to VCSE partners.

- Audit services through mystery shopping, providing feedback on quality of care.

Example of good practice

Outcomes focused evaluation: the Out-of-hospital Care Models programme for people experiencing homelessness.

Since 2020, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), through the Treasury Shared Outcomes Fund, allocated £16million of funding across 17 local areas to pilot out-of-hospital care for people experiencing homelessness.

The programme aimed to reduce discharges to the street, readmissions, unplanned hospital attendance and homelessness, as well as support improvements in individual’s health and wellbeing.

A comprehensive evaluation of the programme (2021-23) evidenced the performance of (and learnings from) out-of-hospital care implementation. Adopting an outcomes-focused methodology, the study captured economic data, individual feedback on health outcomes (QALYs), preferences, experience of care and the real-life stories of those experiencing homelessness.

Involving people with lived experience in all aspects of the evaluation was crucial to the study. Participating as specialist advisors and peer researchers, individuals helped enabled the team to capture an authentic and ‘real’ voice about the effectiveness of the programme.

For example, in Cornwall, over the period of a year, the cost of healthcare for one individual after being enrolled into the programme was reduced by over a quarter from £40,400 to £29,200. The individual’s quality of life drastically improved from sleeping rough, to living in a house and receiving the support he needed to manage his diabetes, leg amputation and general health.

Such outcome-focused results demonstrate the positive impact on people’s lives as well as the economic benefit to broader public budgets and to society.

Digital dashboards have also been developed to capture ongoing data by site, enabling routine gathering, analysis, and comparison of trend data for individual providers, ICSs, local government areas and the nation against benchmarks. These dashboards are a valuable management tool for monitoring and is key in driving long-term service improvements.

Further information is available in online project case stories and dashboards

Example of good practice

Developing a public health approach to sex work in Yorkshire and Humber.Like other inclusion health groups, sex workers have far worse health outcomes than the general population and often experience multiple disadvantage. They are overlooked as an individual population and face significant stigma and inequalities in accessing NHS care.

On behalf of the Association of Directors of Public Health, OHID and UKHSA worked with NHSE to undertake a scoping to better understand the health and wellbeing needs of sex workers across Yorkshire and Humber. The report made a set of recommendations including developing a public health approach to sex work. This led to the establishment of a steering group across the Yorkshire and Humber region to oversee the work.

The approach includes an associated framework for action, the overarching element being around improving health equity, outcomes and inclusion and reducing stigma. It focusses on four key themes: ensuring equitable access to services, delivering person-centred services, improving wider social and economic conditions and partnership work.

A public health approach shifts the focus upstream towards preventing and reducing adverse health consequences of sex work rather than solely focusing on treating these consequences when they occur. Additionally, utilising a public health approach provides an opportunity to not only focus on the health and wellbeing of sex workers, but also the wider determinants of health too. The partnership arrangements now in place within ICS’ provide a real opportunity to address their needs systematically in a truly integrated way.

The steering group meets regularly and brings together women with lived experience, ICBs, NHS providers, sex work services, local authorities, police, and academics. To build on this work, it has also led to a collaboration led by academics to consider a multi-sited evaluation of third sector-led health interventions for street sex workers in the North of England.

Next steps

Integrated care systems

Integrated care systems should use this framework as a practical resource to develop and deliver integrated plans to improve inclusion health. Applying this framework will help ICSs deliver on healthcare inequalities priorities set out in operational planning implementation guidance to restore services inclusively and accelerate preventative programmes, particularly through the Core20PLUS5 approach. This will also support ICBs to fulfil their statutory duty on reducing health inequalities

Good plans will:

- be integrated with other activity, not siloed

- be based on engagement across the ICP and coproduction with people with lived experience

- consider delivery services in all parts of the NHS, particularly in primary care, urgent and emergency care, community care and acute services

- consider the balance of specialist and mainstream services as well as workforce plans

- include action at each level of an integrated care system (system, place and neighbourhood)

Changes to funding approaches may be needed to deliver change on inclusion health and shift resource where it is needed most. There is a range of potential funding sources for work on health inequalities. This will require senior leadership discussion and commitment to understanding the true costs of supporting inclusion health through different services so that the resource can be used more effectively.

Regional teams across the health system

Regional teams across NHSE, OHID and UKHSA play an important role in championing inclusion health and supporting systems to deliver good practice. And have played a key role in developing this framework. Regional teams can build on this work by:

- Raising awareness of this framework through established routes.

- Supporting systems to understand the needs of their local populations, benchmarking activity, sharing good practice and helping to solve barriers to improvement.

- Signposting people to references in and beyond the framework.

- Sharing best practice with national teams and highlighting barriers which require national attention.

- Working with NHS England to establish effective programmes such as the HIU service.

NHS England

We will continue to highlight the need for practical action to improve inclusion health as part of our wider Healthcare Inequalities and Improvement programme and work across NHS England to ensure the needs of people at risk of health inequalities and in inclusion health groups are reflected in relevant policies and plans, for both adults and children and young people.

We will work across NHS England and with key partners such as OHID and UKHSA, other government departments and national partners to develop joined up approaches to inclusion health and better enable action in integrated care systems and at a local level, including through improvements to data and evidence. For example, we have heard that lack of funding for outreach homelessness services and short-term funding brings challenges for this group of patients. We need a collaborative and a long-term funding approach to deliver sustainable healthcare support for people in inclusion health groups.

We will continue to work to develop initiatives and resources to ensure the NHS workforce has the knowledge, skills and confidence to address health inequalities, including those experienced by people in inclusion health groups.

We will also share learning and best practice across the nation and will:

- Share examples of best practice gathered through our call for evidence through the inclusion health space on the NHS Futures Collaborative Platform. The platform will provide an interactive space for people to share good practice in relation to the framework and support each other to solve problems.

- Share best practice from our Core20PLUS5 community connectors which include people from inclusion health communities working with systems to deliver improvement in each of the five clinical areas identified in Core20PLUS5.

- Build on the work of Inclusion health network supported by Pathway, Groundswell and the Kings Fund and explore how we can spread good practice and support other ICSs who want to go further faster.

Appendix A: Selected statistics on the health of inclusion health groups

Mortality of inclusion health group

- A systematic review and meta-analysis found that mortality in high-income countries was approximately 12 times higher in women in inclusion health groups compared with the general population, and 8 times higher in men.

- The average age of death for patients experiencing homelessness and rough sleeping is 43 years for women and 45 years for men.

- Gypsy and Traveller communities are estimated to have life expectancies of between 10 and 25 years shorter than the general population.

- Female sex workers in London have a mortality rate that is 12 times the national average.

Mental health and physical health

- More than two thirds (68%) of female sex workers in London meet the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Asylum seekers are 10-20 times more likely to suffer from PSTD compared with the general population due to war, violence and living in fear.

- People in the criminal justice system experience rates of mental ill health three times higher compared to the general population.

- The rate of suicides in boys aged 15-17 who have been sentenced and remanded in custody are 18 times higher than the rate of suicides in boys in the general population.

- The suicide rate among Irish Travellers is as high as 6 times that of the non-traveller population.

- The homeless population has a greater number of missing and decayed teeth and fewer filled teeth with almost a third (32%) reporting dental pain.

- Over half (58%) of trafficked female sex workers reported having dental problems.

- Many trafficked sex workers experienced physical violence, with 8% having experienced direct assault to the face.

Child health

- Over a quarter of children with parents who experience homelessness and rough sleeping feel depressed (26%) or socially isolated (28%) because of living in temporary accommodation.

- Roma, Gypsy, and Traveller communities experience high infant mortality rates with 18% of women having experienced the death of a child.

Appendix B: Roles and responsibilities of different organisations

NHS England

While the fundamental social drivers of health inequalities lie outside the healthcare system, the NHS can make a central contribution to narrowing inequalities in healthcare outcomes by tackling disparities in healthcare provision – in access to services and patient experience. NHS England has therefore set out a programme to reduce inequalities in health service delivery in line with the strategic intent set out in the NHS Long Term Plan.

The NHS focus on tackling inequalities is underpinned by new legal duties. NHS England and ICBs have duties to have due regard to reducing inequalities between persons with respect to their ability to access health services, and the outcomes achieved by the provision of health services.

In broad terms, NHS England’s role is to support local systems to produce Joint Forward Plans, setting the direction, ensuring accountability, mobilising expert networks, enabling improvement, setting goals and supporting monitoring, and driving transformation – the Framework is a core part of that work, but other actions will be needed.

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID)

OHID, part of the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), focusses on improving the nation’s health, preventing ill health, and reducing health disparities. OHID is responsible for building the evidence base, leading, and developing policy, and supporting the effective delivery of services around inclusion health. With a focus on health improvement, OHID works with the NHS and local government to improve access to services, a priority for inclusion health groups.

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA)

UKHSA is an executive agency sponsored by DHSC and is responsible for protecting communities, including those in inclusion health groups, from infectious diseases and other health threats. UKHSA also has a responsibility to reduce health inequalities caused by infectious diseases and environmental hazards and works with partners and stakeholders such as NHS England and OHID to do so.

This responsibility includes developing the evidence base for excess burden of disease related to infections and environmental hazards, developing surveillance systems to monitor progress, and sharing this information with other partners. UKHSA also has a lead role in responding to incidents and outbreaks in Inclusion Health settings and populations.

Regional teams in the health systems (NHSE, OHID, UKHSA)

NHS England, OHID and UKHSA have regional teams which bridge the gap between the national bodies, and the local integrated care systems (ICSs) and other partners. They work in a collaborative way across organisations and may be ‘blended teams’ though the teams of each organisation have a specific remit.

NHS teams are responsible for the quality, financial, commissioning, and operational performance of NHS organisations in their regions, including access and outcomes for patients from inclusion health groups. OHID regional teams support the delivery of both national and local priorities for improving people’s health, preventing ill health, and reducing health disparities. UKHSA regional teams lead on health protection, with a focus on infectious diseases and other environmental health threats as well as supporting response to incidents and outbreaks in their regions.

Integrated care systems (including integrated care boards and integrated care partnerships)

Integrated care systems (ICSs) are made up of integrated care boards (ICBs) and integrated care partnerships (ICPs). ICSs as a whole are responsible for agreeing local inclusion health strategies with the regions, and then working with providers to implement these locally. They are also responsible for understanding the needs of inclusion health groups locally, and working to improve access and outcomes for these groups, for example through joint strategic needs assessments (JSNAs).

ICBs have developed and published delivery plans with partners for the integrated care strategy and the joint health and wellbeing strategy as set out in the five-year joint forward plans (JFPs).

Each ICB must also ensure that patients and communities (including those from inclusion health groups) are involved in the planning and commissioning of services. ICBs are responsible for commissioning primary care (including primary care practices that focus on the needs of inclusion health groups) and a range of public health functions.

ICPs are a statutory committee jointly formed of ICBs and local authorities within an ICS area, are responsible for ensuring partnership and collaboration between NHS bodies, local authorities, voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) organisations and wider partners. This includes ensuring collaboration over commissioning of services to meet the needs of their population.

General Practice and Primary Care Networks

General Practice has an essential role to play in addressing inclusion health, working in partnership with other system partners to prevent ill health and manage long-term conditions amongst socially excluded groups.

Primary care networks (PCNs) are the building blocks of integrated neighbourhood teams, and one of the main delivery partners of local place-based partnerships. As part of the Tackling Neighbourhood Health Inequalities Designated Enhanced Service (DES) specification (part of the GP contract), many PCNs have a nominated health inequalities lead, facilitating the join-up and sharing of learning and practice with provider trust and ICB SROs for health inequalities.

The Fuller Stocktake highlighted the critical role of primary care in both prevention and tackling health inequalities. Integrated neighbourhood teams can support this work by providing capacity to identify and reach out to communities who find it difficult to engage with health services, building on the learning from community outreach models of care that helped to increase uptake of the Covid-19 vaccination.

Local authorities

Local authorities are core members of ICPs, represented by the Local Government Association (LGA) and play a key role in inclusion health. Local authorities have public health teams which are an integral part of health prevention and population health improvement in local areas. They also have teams such as housing which have a responsibility to work with agencies such as the NHS to improve access and outcomes for inclusion health populations at a community level.

Councils are uniquely placed to positively influence many of these wider determinants, such as housing, education, the environment, economic growth and skills. They work hand in hand with communities, people with lived experience, the NHS, businesses and many others to create the conditions necessary for good health. Prevention is a key focus of local authorities, and inclusion health populations are a key group to support in the prevention of ill-health, and promotion of good health.

Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE) organisations

VCSEs are an important partner in the design and delivery of inclusion health services, and usually form part of ICPs. they have a responsibility to advocate for, represent and amplify the voices of people in inclusion health groups. They should also be involved in co-designing and co-delivering policy related to inclusion health, by working with national, regional, and local NHS bodies and other system partners.

Hospitals and trusts

Hospitals and trusts provide various NHS services to a local area and have a responsibility to ensure their care is accessible to all. They are responsible for ensuring that frontline staff and team leaders have the skills and confidence needed to support socially excluded groups and provide adaptations for patients when needed.

Hospitals and trusts have a duty to that ensure services are provided in an integrated way where this might reduce health inequalities including those experienced by inclusion health groups.

Hospitals and trusts also have a duty to refer where a person in contact with NHS services is homeless or threatened with homelessness.

People with lived experience

Evidence tells us that people with lived experience should be engaged by all these agencies to ensure that people and communities are involved at every stage of decision making, and that partnership working is embedded throughout all structures and policies. Working with people with lived experience is essential for improving access, experience, and outcomes of health services. There is a legal and moral duty to involve people with lived experience that exists because the evidence shows that it works.

Other key players

There are many key players in relation to inclusion health, and this is by no means an exhaustive list. Working collaboratively between agencies is essential to improve the healthcare access, experience, and outcomes for socially excluded people, and this goes beyond the NHS.

For instance, the Care Quality Commission are central to ensuring there are good quality services available for people from inclusion health groups. Safeguarding Adults Boards also are vital to ensure that vulnerable people are protected, and where there are failings, that they are learnt from.

Other government agencies also play a significant role for specific inclusion health groups, such as the Home Office and Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, and HM Prison and Probation Service. At a more local level, agencies such as the police also work together with other key players to support people from inclusion health groups.

Glossary

|

Core20PLUS5 |

A national NHS England approach to inform action to reduce healthcare inequalities at both national and system level. The approach defines a target population – the ‘Core20PLUS’ – and identifies ‘5’ focus clinical areas requiring accelerated improvement. |

|

Inclusion health groups |

Groups in society that suffer from social exclusion in healthcare settings. These include people who experience homelessness, drug and alcohol dependence, vulnerable migrants, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, sex workers, people in contact with the justice system and victims of modern slavery. |

|

Integrated care board (ICB) |

A statutory NHS organisation which is responsible for developing a plan for meeting the health needs of the population, managing the NHS budget and arranging for the provision of health services in a geographical area. |

|

Integrated care system (ICS) |

Partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up health and care services, and to improve the lives of people who live and work in their area. These organisations include, but are not limited to, integrated care boards, integrated care partnerships, local authorities and place-based partnerships` |

|

NHS bodies |

Organisations directly within the NHS such as (but not limited to) NHS England, NHS trusts, integrated care boards, primary care networks. |

|

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID) |

A part of the Department of Health and Social Care that focuses on improving the nation’s health so that everyone can expect to live more of life in good health, and on levelling up health disparities to break the link between background and prospects for a healthy life. |

|

Primary Care Network (PCN |

Groups of practices in which GP practices work together with community, mental health, social care, pharmacy, hospital and voluntary services in their local areas. |

|

UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) |

A agency of the Department of Health and Social Care that is responsible for protecting every member of every community from the impact of infectious diseases, chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear incidents and other health threats |

|

Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprise (VCSE |

A term to describe non-profit organisations including charities, public service mutuals and social enterprises |

|

Wider system partners |

Organisations in the health system that work in partnership with NHS bodies such as voluntary, community and social enterprise VCSE organisations, local authorities, and provider collaboratives |

Useful tools and resources

Guidance and policy

- Inclusion Health: applying All Our Health – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- Homelessness: applying All Our Health – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- NICE Guideline 214 – Integrated health and social care for people experiencing homelessness

- Homeless and Inclusion Health standards for commissioners and service providers

- Guidance for considering the needs of asylum seekers and refugees in commissioning health services

- Migrant health guide – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

- Guidance on the duty to refer

- Guidance on addressing health inequalities in the criminal justice system

- Statutory guidance on working in partnership with people and communities

- Health and justice framework for integration 2022-2025

- NHS Guidance: Action on digital inclusion

Data resources

- Spotlight – Improving Inclusion Health Outcomes

- Fingertips – Public Health Data

- Statistical profile of severe multiple disadvantage

- Public Health Outcomes Framework – Data on Health Inequalities

- Health-related quality of life and prevalence of six chronic diseases in homeless and housed people – BMJ Open

- Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Dashboard

Training resources

- Royal College of General Practice training

- Online inclusion health course – Pathway

- New Inclusion Health session added to All Our Health programme – eLearning for healthcare (e-lfh.org.uk)

- A brief introduction to inclusion health (fairhealth.org.uk)

- Inclusion Health Education Mapping and Review – Full Report.pdf (hee.nhs.uk)

- Pathway’s Inclusion Health Mapping and Review

Self-assessment tools

- VCSE Inclusion Health Audit Tool

- Inclusion Health Self-Assessment Tool for Primary Care Networks

- Health Equity Assessment Tool (HEAT) – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Other information and resources

- Beyond Pockets of Excellence: Integrated Care Systems for Inclusion Health

- What works in inclusion health: overview of effective interventions for marginalised and excluded populations – The Lancet

- From health for all to leaving no-one behind: public health agencies, inclusion health, and health inequalities – The Lancet Public Health

- Inclusion health: addressing the causes of the causes – The Lancet

- Homeless and Inclusion Health Programme – The Queen’s Nursing Institute (qni.org.uk)

- Toolkit for ICBs and PC Commissioners access to healthcare for asylum accommodation – DOTW

- Health inequalities and Gypsy, Roma, Traveller communities

- Supporting people experiencing homelessness in an accident and emergency setting

Acknowledgements

This National framework for NHS action on inclusion health has been developed in partnership with South Central and West Commissioning Support Unit. A range of partners and stakeholders contributed to development of the framework, including people with lived experience, the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, the UK Health Security Agency, VCSE organisations, regional teams across NHSE, OHID and UKHSA regional teams and ICSs.

For further information or questions relating to this document, contact NHS England’s Health Inequalities Improvement Team: england.healthinequalities@nhs.net.

Publication reference: PRN00807