Summary

Climate change threatens the health of the population and the ability of the NHS to deliver its essential services in both the near-term and longer term.1 For this reason, the NHS became the first national health system in the world to commit to decarbonise its operations, setting a clear target for net zero by 2045 for its total carbon footprint, with an 80% reduction by 2036 to 2039.2 This commitment gained legislative footing with the Health and Care Act (2022).3

More frequent and severe floods and heatwaves, and worsening air pollution are among the impacts the UK is already experiencing in our changing climate, with estimated total excess mortality of 2,803 in England during the record-breaking temperatures of summer 2022.4 Conversely, hitting our national net zero target will save over 2 million life years through cleaner air, healthier cities, and a more resilient health service.5

The NHS fleet is the second largest fleet in the country, consisting of over 20,000 vehicles travelling over 460 million miles every year. This fleet, combined with the impact of commissioned services and staff travel, directly contributes to the 36,000 deaths that occur every year from air pollution. This burden is borne disproportionately by those with pre-existing health conditions, older people, and children.6

The NHS recognises its role as an anchor institution and is taking ambitious action to tackle the twin challenges of climate change and air pollution. Indeed, many of the actions to cut carbon emissions also reduce air pollution which leads to direct and quantifiable impacts on health while also addressing health inequality. The benefits to society of implementing the commitments set out in this strategy are valued at over £270 million each year, with over £59 million saved per year by the NHS, able to be re-invested into patient care.

The strategy has been developed through extensive engagement with clinical groups and patients, public health experts, and representatives from across the NHS. There is strong support from the system’s 1.4 million staff, with over 9 out of 10 wanting to see the NHS deliver on its net zero ambitions.7

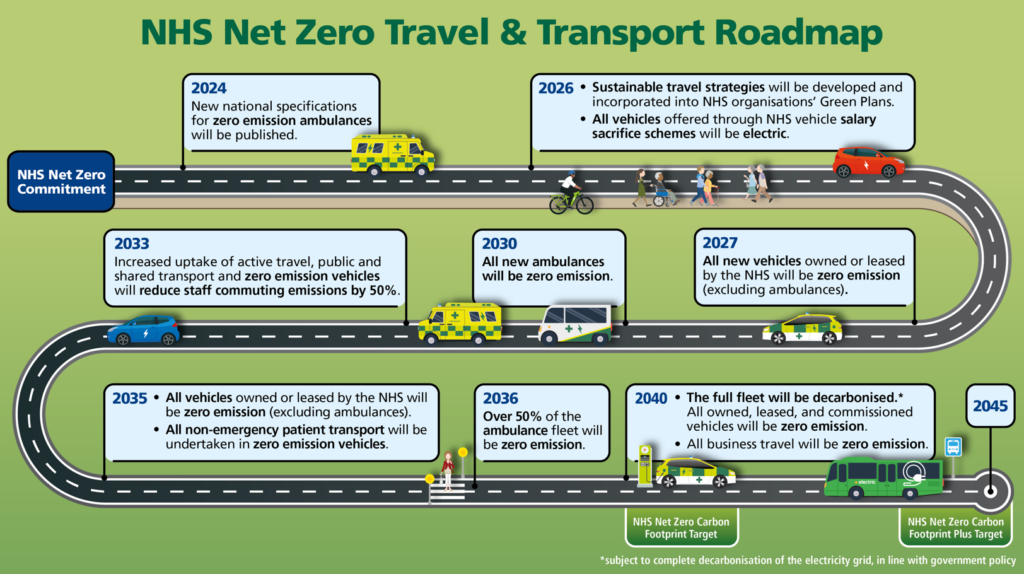

The NHS will have fully decarbonised its fleet by 2035, with its ambulances following in 2040. Several key steps will mark the transition of NHS travel and transportation:

- By 2026, sustainable travel strategies will be developed and incorporated into trust and integrated care board (ICB) green plans.

- From 2027, all new vehicles owned and leased by the NHS will be zero emission vehicles (excluding ambulances).

- From 2030, all new ambulances will be zero emission vehicles.

- By 2033, staff travel emissions will be reduced by 50% through shifts to more sustainable forms of travel and the electrification of personal vehicles.

- By 2035, all vehicles owned and leased by the NHS will be zero emission vehicles (excluding ambulances) and all non-emergency patient transport services (NEPTS) will be undertaken in zero emission vehicles.

- In 2040, the full fleet will be decarbonised. All owned, leased, and commissioned vehicles will be zero emission.

This strategy describes the interventions and modelling underpinning these commitments, walking through each of the major components of the NHS fleet and outlining the benefits to patients and staff. A forthcoming net zero travel and transport implementation toolkit and technical support document will also be provided to trusts and systems to aid local and regional delivery.

1. Introduction

Delivering high quality healthcare across the country brings with it the need for a complex array of transport networks between hospitals, clinics, communities, and suppliers, with just under 10 billion road miles per annum (3.5% of the UK total) directly related to the NHS. As the biggest employer in Europe and the fifth largest employer in the world, 1 in every 25 working age adults are devoted to providing care. The health service is distributed across 18,000 acute care, mental health, ambulance, and community services buildings, with a further 9,000 buildings in general practice. Over 20,000 vehicles are owned and leased by the NHS for use in a range of care settings, constituting a fleet second only to that of the Royal Mail in size, nationally.

The NHS is directly addressing its responsibility to tackle air pollution and carbon emissions, responding to the health emergency that climate change brings. As medicine advances, health needs change and society develops, the NHS must continually move forward. This strategy proposes an ambitious yet deliverable roadmap to decarbonise NHS travel and transport that maximises return on investment and delivers significant health gains.

Strong progress has already been made, with NHS Innovation delivering the world’s first zero emission emergency ambulance in the West Midlands, and Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust becoming the first NHS trust in the country to fully decarbonise its fleet. There are 7 ambulance trusts trialling 21 zero-emission emergency vehicles, 6 of which are dedicated mental health response vehicles, cutting emergency response times, and reducing demand on traditional double-crewed ambulances. In addition, 12 new electric 19-tonne trucks are already being trialled across the NHS, whilst London Ambulance Service NHS Trust has procured 42 fully electric fast response vehicles. South Central Ambulance Service has purchased 10 electric tactical response vehicles and for the first time ever, drones have been used to deliver vital chemotherapy to the Isle of Wight, reducing a 4-hour journey time by road and sea to a 30-minute flight, minimising waste and treatment delays whilst also reducing carbon.8

The availability of petrol and diesel cars and vans is expected to reduce significantly from 2024 as the Government’s legally binding annual targets on zero emission vehicle sales begin to take force. New diesel or petrol vehicles (under 3.5 tonnes) will be unavailable from 2035. Given the scale and complexity of the fleet, NHS organisations need to make early preparations to ensure the transition to zero emission vehicles maximise the operational cost savings and the health and societal benefits.

This strategy will directly improve the health of patients by reducing harmful air pollution. NOx and PM (compounds of nitrogen oxide, and particulate matter) represent one of the largest environmental threats to health in the UK, with 36,000 deaths a year attributed to long-term exposure.9 This pollution is associated with impacts on lung development in children, heart disease, stroke, cancer, and exacerbation of asthma.10

Vulnerable groups, such as those with underlying medical conditions, older people, and young children, are at a disproportionately high risk from exposure to poor air quality. There are also unequal differences in levels of exposure across the population. People likely to experience higher exposures include those who live close to busy roads, who are more likely to be in low socioeconomic groups. This differential exacerbates health inequalities.9 By reducing harmful emissions from all types of travel and transport, the NHS will contribute to improving air quality and mitigate an avoidable contributor to health harms and inequalities.

Extensive engagement with the NHS workforce and industry experts have underpinned the development of this strategy. With its primary responsibility to ensure the health and wellbeing of the public, it is important that the NHS acts to reduce its own contribution to air pollution and climate change from its travel and transport activities.

The following sections of this strategy provide an overview of the methods and approach taken, the scale of the NHS fleet, business travel and staff commuting, the transition roadmap for NHS travel and transport and the financial case for action.

2. Approach and methods

2.1 Scope

This strategy outlines the economic, health and societal benefits of decarbonising NHS travel and transport, specifically:

- The NHS fleet; vehicles that are owned or leased by the NHS, including emergency ambulances, non-emergency patient transport services (NEPTS) and secondary, community and primary care vehicles.

- Business travel; including travel in private vehicles for NHS business (known as the grey fleet) and other forms of business travel (eg, commissioned transport services).

- Staff commuting; employee travel to and from home to place(s) of work.

The NHS fleet and business travel emissions are part of the NHS Carbon Footprint, those emissions under the direct control of the NHS. The NHS has committed to reducing these emissions by 80% by 2028 to 2032 and to net zero by 2040.

Staff commuting emissions are part of the NHS Carbon Footprint Plus, those emissions indirectly caused by NHS activity, over which the NHS has less control but can influence. The NHS has committed to reducing these emissions by 80% by 2036 to 2039 and to net zero by 2045.

Whilst not the focus of this strategy, the policies and interventions detailed are also relevant to other sections of NHS travel and transport within the carbon footprint, including patient and visitor travel, commissioned health services and the NHS supply chain. Efforts to improve patient choice, eliminate the need for unnecessary journeys through increased efficiency and the provision of care in-community and closer to home are not explicitly covered by this strategy.

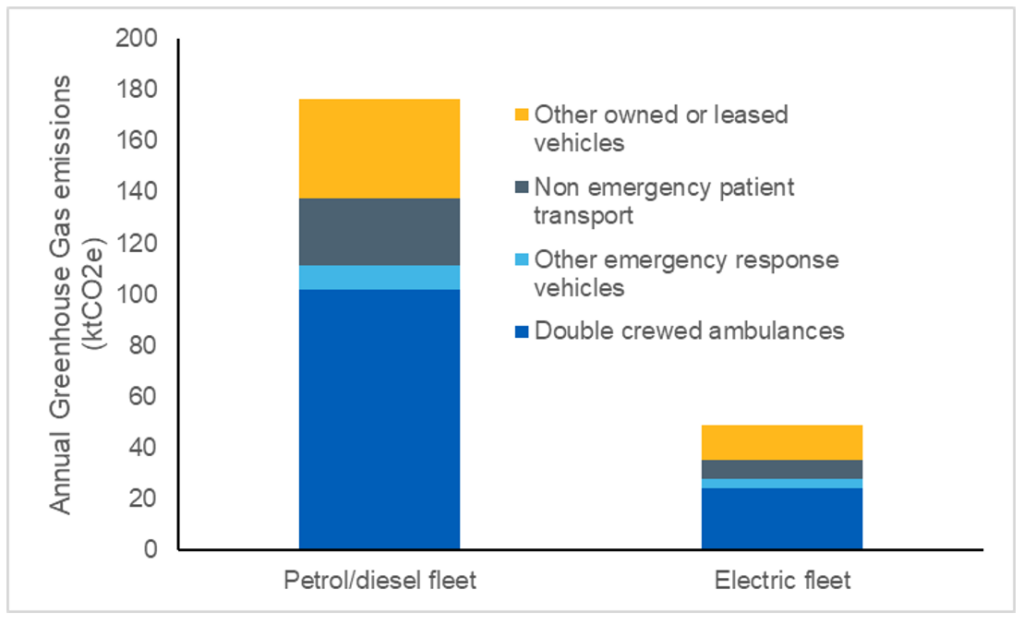

Table 1 shows the annual CO2e emissions associated with these different sources covered by this strategy. The highest travel and transport mode contributor to the NHS Carbon Footprint are emissions from emergency ambulances at approximately 102 kt CO2e/year. For the NHS Carbon Footprint Plus, emissions from all NHS staff commuting are most significant, estimated at around 560 kt CO2e/year.

Table 1. Emissions from across NHS travel and transport modes.

| Broad travel category | Category | Emissions (ktCO2e/year) |

|---|---|---|

| Owned / leased fleet | Double-crewed ambulances (DCA) | 102 |

| Owned / leased fleet | Emergency response vehicles (ERV) | 10 |

| Owned / leased fleet | Non-emergency patient transport services (NEPTS) | 26 |

| Owned / leased fleet | Other | 39 |

| Business travel | Secondary care grey fleet | 87 |

| Business travel | Primary care grey fleet | 52 |

| Business travel | Other (eg, travel associated with commissioned NEPTS services) | 84 |

| Staff commute (Carbon Footprint Plus) | Staff commute | 560 |

2.2 NHS fleet and business travel

To deliver high quality care, the NHS makes use of a large and varied fleet of clinical and non-clinical vehicles, ranging from small cars and light commercial vehicles to NEPTS, rapid response vehicles (RRVs) and emergency ambulances. The composition, annual mileage and emissions of the NHS fleet is outlined in table 2 below.

Table 2. Composition, ownership, annual mileage, and emissions of the NHS fleet.

| Fleet type | Number of vehicles | Ownership | Annual mileage (million miles) | Emissions (ktCO2e/year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double crewed ambulances | 4300 | 74% owned, 26% leased. | 129 | 102 |

| Other emergency response vehicles | 1500 | 60% owned, 40% leased. | 19 | 10 |

| Non-emergency patient transport | 2800 | 10% owned, 90% leased. | 51 | 26 |

| Other owned or leased vehicles | 12200 | 18% owned, 68% leased, 14% hired | 125 | 39 |

| Total owned or leased fleet | 20,800 | n/a | 324 | 177 |

Comprehensive analysis of fleet telematic data, a review of government policy, and detailed stakeholder engagement has informed the development of this strategy. Vehicles have a wide range of operational work patterns and duty cycles and diverse average daily/journey mileage. For example, emergency ambulances have a mean annual mileage of 28,800 and a minimum of 15 hours per day when ignition is turned off. In contrast, ERVs have a lower typical annual mileage (12,900 miles), fewer call outs, and greater down-time when compared to ambulances. Both vehicles typically return to an ambulance base at the end of a shift.

Acute, specialist, community and mental health trusts own or lease approximately 12,200 vehicles, including staff pool cars, Park & Ride shuttles, and estates support vehicles as well as making use of a vast grey fleet when staff use their own vehicles for business purposes – for example to travel between sites or to and from community visits (including to patients’ homes). These journeys constitute a particularly significant source of emissions for primary and community care organisations (annual mileage is estimated at 256,000,000 miles across acute, specialist, community, and mental health trusts, and 155,000,000 further miles across primary care organisations).

The pace of transition across the fleet and regions will differ by vehicle type, market development, geographical context, and operational duty cycle. The analysis underpinning this strategy has enabled the identification of those sections of the NHS fleet that are suitable for a swift transition and those parts that may require further intervention and innovation. For example, NHS England’s Zero Emission Emergency Vehicle (ZEEV) Pathfinder programme has already begun to demonstrate the operational and financial viability of most emergency response vehicles switching to zero emission vehicles.

As of 2022, the uptake of low emission vehicles is 82% and 90% for ambulance and non-ambulance trusts respectively, with 1.1% and 4.5% being zero emission vehicles. Turnover of vehicles ranges from between 5 and 14 years depending on vehicle type.

Electric vehicles reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 70% when compared to their petrol and diesel counterparts (even when charged from the current electricity grid) and do not emit air quality pollutant emissions from the vehicle’s exhaust (as shown in Figure 1.). Electric vehicles also produce lower noise pollution, particularly at lower speeds. This reduction in greenhouse gas emissions will increase as the carbon intensity of the electricity supplied by the national grid reduces.

Figure 1. Emissions savings comparison of electric and diesel/petrol vehicles.

2.3 Staff commuting

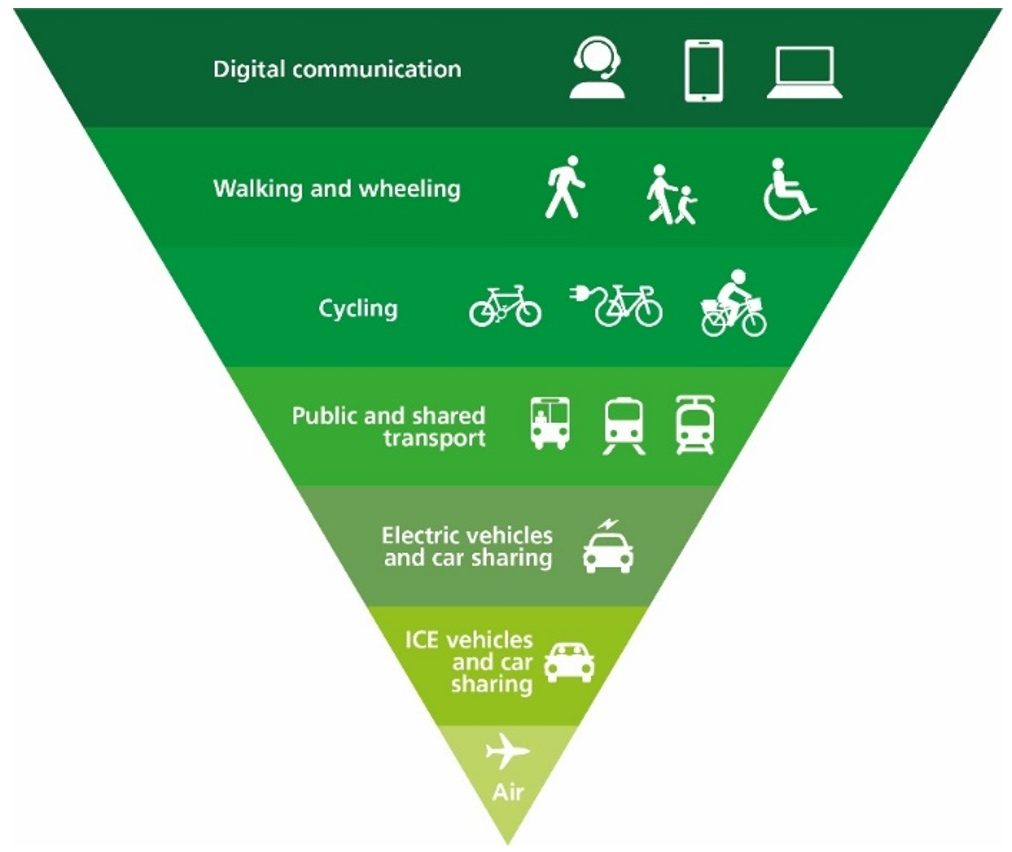

As the largest employer in Europe, many of the 1.4 million NHS staff and health professionals regularly need to commute to and from work. This contributes approximately 560Kt CO2e emissions each year. Most NHS staff commuting journeys currently occur in single occupancy vehicles.11 A shift to less carbon-intensive modes of transportation such as public and active travel (Figure 2) will not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, but also deliver significant health and wellbeing benefits to the individual and wider society.

Physical activity has significant and wide-ranging health benefits including improved cardiovascular, metabolic, and musculoskeletal health; reduced risk of falls and cancer and improved mental health outcomes including reduced incidence of depression and dementia.12 Walking for 30 minutes or cycling for 20 minutes on most days has been shown to reduce all-cause mortality by at least 10%. People who use active travel modes to commute to work have been shown to experience improved psychological wellbeing compared with those who travel by car, to be at a 30% lower risk of type 2 diabetes, and be at 10% lower risk of cardiovascular disease.13 People who commute by active modes of travel tend to be more satisfied with their journey to work than those who travel by car 14 and increasing physical activity can reduce stress, promote health and well-being, and reduce absenteeism at work.12

It is important that NHS organisations account for the specific needs associated with workforce shift patterns and working hours within their locality. Furthermore, much of the care the NHS delivers needs to be done in-person, and some travel options may not be suitable for certain groups, people, or localities. Also, many NHS staff commute to work by car because they need their vehicle to travel between NHS sites or visit patients during their working day. This highlights the important role of locally tailored strategies and place-based leadership in ensuring a just and equitable transition.

Figure 2. The sustainable travel hierarchy.

3. Policies, interventions, and roadmap

A range of interventions are required to support the transition to more sustainable travel and concerted, collective action is required both across the NHS and in collaboration with non-NHS organisations.

These interventions build upon real-world progress made to-date, including electric emergency vehicles currently delivering care across the country and drones used to deliver chemotherapy medicine for the first time ever. Trusts are also acting on supply chain transport; Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust,14 and Gateshead Health Trust 16 are implementing electric cargo bike courier services to replace diesel van transport between sites. Gateshead Health Trust has saved carbon and avoided congestion using e-cargo bikes to deliver samples and stock across the region. Oxford University Hospital Trust found the use of an e-cargo bike to deliver chemotherapy treatments increased reliability and efficiency, whilst mitigating the effect of rush hour traffic on and around the hospital site. Forward-thinking and innovative solutions are being implemented across the country, including at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation Trust which has transformed the way it transports vital medical supplies. A twice-daily riverboat service brings operating theatre equipment along the River Thames, with the last-mile delivery to the hospital sites from the boat terminal done by electric cargo bike. By taking three diesel-powered delivery trucks off the road, the initiative saves 37 tonnes of CO2e per year.17

Ambulances and other emergency response vehicles play a critical role in providing emergency care and must always be able to respond rapidly. To enable this, these vehicles have distinct operational demands, vehicle design specifications, and associated infrastructure requirements. As such, the interventions outlined in this strategy for ambulances ensure the continuation of high-quality care and patient safety, whilst enabling the necessary innovation and evaluation in the transition to electric emergency vehicles. Reflecting the distinction between ambulances and typical cars and vans, all new ambulances will be zero emission by 2030, with interim milestones to ensure an entirely zero emission NHS ambulance fleet from 2040.

There are 7 ambulance trusts currently trialling zero-emission emergency vehicles, and the world’s first zero emission ambulance is in place in the West Midlands. Following the positive response from staff and patients to the vehicles, trusts including South Central, London and North West Ambulance services have started to further integrate electric vehicles into their fleets. The NHS will continue to build on this success, with ambulance trusts on track to pilot the first suite of zero emission ambulances across the country, using the findings alongside those from the ZEEV pathfinder programme to inform an effective wider rollout and transformation throughout the fleet, which will be supported by updated specifications and procurement practices.

The interventions for secondary, primary and community care organisations focus on staff vehicle electrification and the uptake of active modes of travel, to reflect the relatively low number of owned or leased vehicles within the fleet and the significant proportion of business travel undertaken within staff-owned vehicles (eg, visits to patients’ homes and community locations). The interventions will also reduce the significant greenhouse gas emissions associated with staff commuting behaviours.

The proposed actions include salary sacrifice and cycle to work schemes, whereby an employee can lease a new vehicle or bike for a fixed term by sacrificing a part of their salary. This reduces tax, national insurance and pension contributions for the employee and the employer and is key to making new vehicles more affordable for staff. Salary sacrifice can also be used to reduce the cost of other high-value purchases including public transport annual passes as shown at Newcastle Hospitals Foundation Trust.18

Many GPs are already reducing business travel by offering online consultations to patients who prefer to reach their doctor digitally in the first instance, with positive results. GPs are also taking action to reduce the travel emissions of unavoidable journeys (eg, home visits). Practices in Sheffield,19 Exeter20 and Newquay21 have benefited from staff using e-bikes to visit patients and commute, with local partnerships permitting access to discounted schemes for staff. Several staff members at Sloan Medical Centre in Sheffield purchased their own e-bikes on the practice’s cycle-to-work scheme after a trial in partnership with the local authority.19

The pace of transition will differ regionally and across different parts of the NHS’ travel and transport system. This is due to differences in vehicle type, geographical context, working patterns and operational duty cycle. Trusts and ICBs need to consider which interventions are most applicable and feasible to the local context. The following sections outline the policies and interventions across different organisations, the overall transition roadmap, and concludes with the subsequent emissions trajectory over time.

3.1 Ambulance trusts

NHS ambulance trust fleets are specialised and expansive, with approximately 4,300 DCAs, 1,500 other emergency response vehicles, such as rapid response and mental health vehicles, as well as other vehicles supporting NHS services. The scale, complexity and operational planning model of ambulance fleets means greater support is likely to be required to support electrification. Key initial steps already taken include the ZEEV pathfinder programme and the launch of the world’s first electric ambulance. By 2024, new national specifications will be published to create a zero emission option for ambulance trusts. To build on the success of these initiatives, all ambulance trusts will:

Effective planning

Develop a sustainable travel strategy to be incorporated into future Green Plans by 2026 (supported by updated statutory Green Plan Guidance). These should include an infrastructure requirement assessment, including recharging.

Innovate and evaluate

Conduct pilots of the first suite of zero emission ambulances, followed by evaluation and at-scale transformation. This will ensure continuation of high levels of patient safety, while delivering wider rollout.

Update specifications

Work with the National Ambulance Programme Board to develop and publish new national specifications for zero emission DCAs and RRVs informed by trials of current generation battery electric DCAs and RRVs.

Sustainable procurement

Integrate the purchasing of zero emission vehicles into procurement practices, ensuring vehicles part of contracted services and any owned or leased vehicles are aligned with the roadmap targets and interim milestones.

Case study – North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust (NWAS)

- NWAS serves more than 7,000,000 people, with a fleet of over 1,000 emergency and non-emergency vehicles.

- NWAS procured 3 electric vehicles as part of NHS England’s Zero Emission Emergency Vehicle (ZEEV) pathfinder programme: 2 rapid response vehicles and a mental health response vehicle.

- The vehicles were warmly received by staff, and as a result NWAS has decided to purchase 7 fully electric fleet support vehicles, which are expected to:

- result in £3,500 in fuel savings per vehicle per annum

- reduce annual maintenance costs by 20%

- reduce emissions by 283 tonnes CO2 over 5 years

“We are delighted to introduce these 7 new electric vans that have now replaced our diesel workshop support fleet. They carry maintenance equipment between our sites as well as staff when required to keep our emergency ambulances and response vehicles on the road.”

3.2 Integrated care boards (ICBs) and integrated care systems (ICSs)

Given the pivotal role of ICSs in bringing together local organisations to plan and deliver services, they are ideally placed to lead local partnerships to support delivery of travel infrastructure and services necessary to increase sustainable travel. Every ICB has a localised green plan and a board-level net zero lead, responsible for overseeing its delivery. ICBs should work with their ICS partners to prioritise the following actions to progress the transition to lower emission travel:

Effective planning

Develop a sustainable travel strategy to be incorporated into future Green Plans by 2026 (supported by updated statutory Green Plan Guidance). These should include an assessment of the infrastructure requirements for patients, staff, and the public.

Strategic partnerships

Form partnerships with local authorities and local transport authorities to maximise funding and infrastructure opportunities, on behalf of the ICS member organisations.

Sustainable procurement

Integrate the purchasing of zero emission vehicles into procurement practices, ensuring vehicles part of contracted services and any owned or leased vehicles are aligned with the roadmap targets and interim milestones.

Case study – Hull University Teaching Hospitals

- Hull University Teaching Hospitals Trust worked with local authorities and local transport providers to encourage sustainable staff travel between hospital sites.

- Local bus and Park & Ride offers were developed for NHS staff, cycle training and bike lights were provided and cycle facilities were improved on all NHS sites.

- It is estimated that the number of staff driving to work was reduced by 13% in the first year of the Getting To Work Campaign.

- The campaign was well received by NHS staff.

“I no longer feel the stress of finding a car parking space in the morning or face fighting my way through rush-hour traffic and traffic jams, so this new way of travelling to work has also benefitted my overall wellbeing”.

3.3 Secondary, community and primary Care

Secondary and community care trusts own or lease a combined total fleet of approximately 10,000 vehicles, including staff pool cars, Park & Ride shuttles, and estates support vehicles. They also operate a vast grey fleet. The primary care fleet is almost exclusively grey fleet and has an estimated annual mileage of 155,000,000 miles per year. Secondary, community and primary care providers should implement the following policies and interventions:

Effective planning

Develop a sustainable travel strategy to be incorporated into future Green Plans by 2026 (supported by updated statutory Green Plan Guidance). These should include an assessment of the infrastructure requirements for patients, staff, and the public.

Salary sacrifice

- All vehicles offered through NHS vehicle salary sacrifice schemes to be electric by 2026.

- Create and promote cycle-to-work salary sacrifice schemes, including e-bikes.

Sustainable procurement

Integrate zero emission vehicles into procurement practices, ensuring vehicles part of contracted services, and any owned or leased vehicles are aligned with the roadmap targets and interim milestones.

Case study – E-Bikes for GP home visits and travel

- Some GPs are already taking action to reduce their travel emissions from home visits and other business mileage.

- Sloan Medical Centre in Sheffield, Newquay Health Centre in Newquay and Pinhoe and Broadclyst Medical Practice in Devon have reduced emissions from their doctors’ journeys around the community by transitioning to the use of e-bikes.

- They have all procured the bikes in different ways (eg, pool e-bikes in partnership with local authority, purchasing a fleet of e-bikes), demonstrating how different models can work according to providers’ preferences and circumstances.

- Following their positive experiences using the bikes to commute and visit patients, several staff purchased one of their own on a cycle-to-work salary sacrifice scheme.

“It now takes 15 minutes to get to a patient that used to take 45 minutes… On a bike, I don’t have to worry about where I am going to park, I just turn up right outside the door, saving time, and then it’s on to the next home visit”.

Secondary, community and primary care providers should evaluate their local context and consider implementing the following policies and interventions:

Cross cutting

- Include an introduction to sustainable travel and the travel hierarchy in staff inductions.

- Maximise the use of route planning tools to drive efficiency in NHS journeys.

EV transition and business travel

- Establish electric vehicles and e-bike pools and provide access to staff for business journeys and/or commuting.

- Explore schemes to incentivise low carbon business travel reimbursement (eg, EVs, active travel, public transport).

Sustainable travel

- Formalise lift sharing arrangements for staff commuting (through third-party provider or internal process).

- Ensure secure bike storage and changing facilities and improve on and off-site walking and cycling routes.

- Create staff rewards for sustainable modes of travel (eg, discounts at on-site shops and cafes).

- Explore salary sacrifice for public transport passes, to make commuting more affordable.

- Consider providing regular shuttle buses or free public transport between sites for multi-site trusts.

Case study – Hospital Hoppers go electric for greener commutes

- A new fully electric inter-site shuttle bus service has been rolled out in Leicester, to provide a more sustainable travel option for staff and patients travelling between Leicester Royal Infirmary, Leicester General Hospital and Glenfield Hospital.

- The new ‘Hospital Hoppers’ are being introduced through a partnership between University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, Leicester City council and the service operator.

- Compared with private cars and diesel buses, these electric alternatives reduce emissions, boost air quality and tackle traffic congestion.

- The routes have also seen upgraded bus shelters providing real-time information and a “text-to-speech” facility for audible bus arrival times to support people with visual difficulties. A new bus lane installation will also reduce journey times, making the trip even more convenient.

“The new hospital hoppers are a great opportunity to work with partners, to reduce our carbon footprint and to make it easier for people to access health care in Leicester.”

3.4 The NHS net zero travel and transport roadmap

The roadmap below summarises the major milestones to net zero travel and transport in the NHS, as part of meeting the NHS Carbon Footprint targets. With a phased introduction of zero emission vehicles and sustainable travel modes into NHS travel and transport activities, the NHS will have decarbonised its fleet by 2035, with its ambulances following in 2040.

Net Zero travel and transport roadmap

The roadmap shows the following milestones:

2024: New national specifications for zero emission ambulances will be published

2026:

- Sustainable travel strategies will be developed and incorporated into NHS organisations’ Green Plans

- All vehicles offered through NHS vehicles salary sacrifice schemes will be electric

2027: All new vehicles owned or leased by the NHS will be zero emission (excluding ambulances)

2030: All new ambulances will be zero emission

2033: Increased uptake of active travel, public and shared transport and zero emission vehicles will reduce staff commuting emissions by 50%

2035:

- All vehicles owned or leased by the NHS will be zero emission (excluding ambulances)

- All non-emergency patients transport will be undertaken in zero emissions vehicles.

2036: Over 50% of the ambulance fleet will be zero emission

2040:

- NHS Net Zero Carbon Footprint target – the full fleet will be decarbonised (subject to the complete decarbonisation of the electricity grid, in line with Government policy)

- All business travel will be zero emission

2045: NHS Net Zero Carbon Footprint Plus target

Download the roadmap as a PDF (556Kb)

4. The public health, societal, and financial case for action

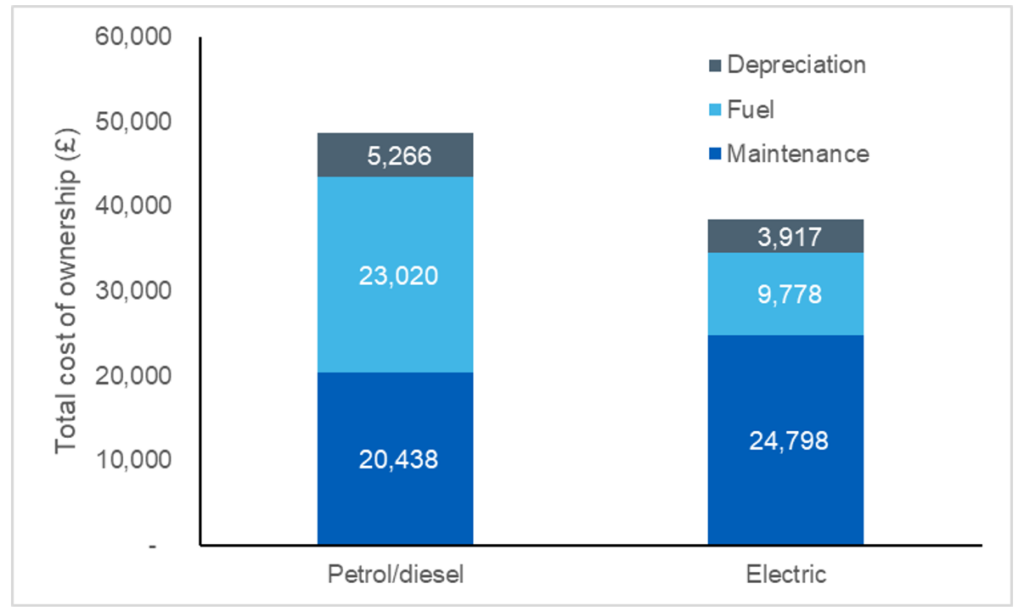

This section considers the full cost of ownership of electric vehicles (purchase costs, residual values, fuel, and maintenance costs) compared to the petrol and diesel vehicles. There is also a consideration of the types and costs of electric charge stations required to support electrification. The section ends with detailing the wider health and societal benefits associated with the transition to more sustainable modes of transport.

4.1 Cost of ownership and charging infrastructure

Electric vehicles are already cheaper than petrol and diesel vehicles over their lifetime and are expected to reach full purchase price parity in 2026.22 For example, Figure 5 represents the value differential between petrol/diesel and electric vehicles for an average emergency response vehicle using present day figures.

Figure 5. Value differential between electric and petrol/diesel vehicles.

Detailed ambulance telematics data has been used to calculate the scale of electric vehicle refuelling infrastructure required to support a zero emission emergency fleet. These vehicles would need to charge whilst they are stopped for other reasons, which would require ringfenced charging capacity at all ambulance stations and emergency departments. These calculations estimated that such a fleet would require around 5,500 charge points of varying power across 1,500 NHS locations.

Most other NHS vehicles would be able to recharge slowly overnight, when demand for electricity at NHS sites is lowest and cheapest. Such charging arrangements would remove the need to upgrade the electricity supply in most NHS locations. Also, vehicles would typically only need to charge once or twice a week based on current usage patterns, which means several vehicles could share each charge point.

Electrical capacity upgrades may also be required in some NHS locations to support the uptake of electric vehicles. These upgrades form part of the broader decarbonisation of the national grid. The upgrades will support the transformation of travel and transport but are also relevant to NHS energy and estate decarbonisation (eg, the replacement of boilers with air source heat pumps).

Upgrades to the grid and electrical infrastructure are estimated to cost just over £100 million to meet the requirements outlined in this strategy. Reforms implemented by Ofgem from April 2023 alongside RIIO-ED2 are expected to significantly change current connection costs, by reducing or removing the customer contribution to reinforcement costs for new connections to the distribution network.23 The capital investment associated with increasing electrical capacity at NHS sites is therefore expected to be met within the broader decarbonisation of the national electricity grid.

The faster the NHS fleet transitions; the faster and larger the net revenue savings can be realised alongside faster and larger cumulative reductions in harmful emissions. Based on the government’s fuel and electricity price projections, annual savings associated with electric vehicles from a reduction in maintenance and fuel costs are realised in the short term and increase significantly from 2032 as the ambulance fleet electrifies. With the cost of new electric vehicle purchase soon to reach parity with diesel and petrol models, and the charging infrastructure requirements representing a modest capital pressure, fully implementing the NHS Net Zero Travel and Transport Strategy will result in over £59 million saved every year, with savings directly invested into patient care.

4.2 Benefits to health, society, and the NHS

As well as the direct cost savings to the NHS expected from electrification of travel and transport, there are health benefits associated with reduced air pollution and increased physical activity through active travel. The key pollutants associated with health impacts of air pollution are nitrogen oxides and particulate matter PM2.5. There are also wider societal benefits associated with reduced carbon emissions, reduced pollution, and reduced traffic. In addition to the £59 million annual expected operational savings, the wider benefits of the transition to net zero NHS travel and transport are estimated to be over £270 million a year (Table 4).

Table 4. Long term annual health and societal benefits and NHS savings of NHS Travel and Transport transition.

| Activity | Annual health benefits (£m) | Annual societal benefits (£m) | Annual direct NHS savings (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHS fleet and business travel | 2.1 | 77.6 | 59.0 |

| Modal shift | 38.3 | 112.7 | 0.0 |

| Electrification of personal vehicles | 1.3 | 45.2 | 0.0 |

| Total | £41.7m | £235.5m | £59.0m |

The reduction in business travel and shift in commuting practices will be underpinned by wider transformation outside of the NHS remit (eg, improvements to local public transport networks). It is expected that a significant proportion of the funding needed to meet this cost would be provided by Government schemes (eg, £2 billion of funding available through the Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy24 and the £3 billion available through the National Bus Strategy).25 This highlights the importance of NHS services engaging local transport authorities to maximise the benefits of the placed based approach of ICSs to ensure sustainable, holistic transport planning.

5. Next steps

The direction, scale and pace of change outlined in this strategy have been informed by underlying modelling to maximise the significant economic, health and societal benefits associated with the transition to net zero.

The strategy outlines the importance of developing sustainable transport strategies and the benefit of collaboration with non-NHS organisations. Whilst further piloting and evaluation is required for specialist elements of the fleet (eg, ambulances), the strategy provides policies and interventions to catalyse the transition of the general fleet, including grey fleet in the coming years. These policies and interventions will build upon the extensive progress made to date.

The evidence-based targets laid out in this strategy provide ambitious and credible targets for net zero emissions. Within the broader UK Government framework for decarbonisation, this Net Zero Travel and Transport Strategy ensures the NHS is well-placed to meet its commitments within the Health and Care Act (2022) and to become the first health system in the world with net zero travel and transport.

6. References

- UK Government. UK Climate Change Risk Assessment. 2022.

- NHS England. Delivering a Net Zero National Health Service. 2022.

- UK Government. Health and Care Act 2022. 2022.

- UK Health Security Agency, Office for National Statistics. Excess mortality during heat-periods: 1 June to 31 August 2022. 2022.

- Milner J, Turner G, Ibbetson A, Colombo PE, Green R, Dangour AD, Haines A, Wilkinson P. Impact on mortality of pathways to net zero greenhouse gas emissions in England and Wales: a multisectoral modelling study. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2023 Feb 1;7(2):128-36.

- Whitty C, Jenkins D. Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2022: Air Pollution. Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK. 2022 Dec 8.

- NHS England. Public and staff opinions. 2022.

- NHS England. Drone deliveries of vital chemotherapy to the Isle of Wight. 2022.

- Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants. Long-term exposure to air pollution: effect on mortality. 2009.

- Gowers AM, Miller BG, Stedman JR. Estimating Local Mortality Burdens associated with Particulate Air Pollution. London: Public Health England; 2014.

- Department for Transport. National Travel Survey: 2021. 2022.

- The Role of Active Travel in Improving Health. 2017.

- World Health Organization. Walking can Help Reduce Physical Inactivity and Air Pollution, Save Lives and Mitigate Climate Change. 2022.

- Chatterjee K, Chng S, Clark B, Davis A, De Vos J, Ettema D, Handy S, Martin A, Reardon L. Commuting and wellbeing: a critical overview of the literature with implications for policy and future research. Transport reviews. 2020 Jan 2;40(1):5-34.

- Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Pedal Power Drives Improved Service And Greener Deliveries. 2021.

- Gateshead Health NHS Trust. Gateshead NHS goes green with new electric transport. 2021.

- Greener NHS. Supply chain – London. 2023

- Benefits Everyone. Trust Travel Scheme.

- Greener Practice. E-bikes take a Sheffield GP Practice by storm. 2022.

- Exeter Chamber. NHS Doctors Get On Their Bikes For Home Visits Thanks To Co Bikes. 2021.

- NHS Doctors Ditch Cars For E-Bikes To Hasten Home Visits. 2020.

- Department for Transport. Zero Emissions Vehicle Mandate and non-ZEV Efficiency Requirements Consultation-stage Cost Benefit Analysis. 2023.

- Office of Gas and Electricity Markets. Access and Forward-Looking Charges Significant Code Review: Decision and Direction. 2022.

- Active Travel England. The second cycling and walking investment strategy (CWIS2).

- Pickett L, Dallas M, Stewart I. The National Bus Strategy: Bus policy in England outside London. The House of Commons Library. 2022.

7. Glossary

- CO2 – Carbon dioxide

- CO2e – Carbon dioxide equivalent

- DCA – Double crewed ambulance

- ERV – Emergency response vehicle

- EV – Electric vehicle

- ICB – Integrated care board

- ICS – Integrated care system

- Kt – Kilotonne

- NEPTS – Non-emergency patient transport services

- NOx – Oxides of nitrogen

- NWAS – North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust

- PM – Particulate matter

- RRV – Rapid response vehicle

Publication reference: PRN00712