Foreword

Play is a vital part of childhood – and that shouldn’t change when a child becomes unwell. Health play services help young people have a voice, feel safe, reduce anxiety, and improve outcomes. They change how children experience health services and that can have long-lasting effect on their engagement with healthcare well into adulthood.

NHS England and Starlight formed the Taskforce on Children’s Play in Healthcare and with input from more than 60 health professionals and young people, these are the first national guidelines and standards for commissioning and delivering health play services in England.

It’s an important step, but it’s only the start. These documents will support system leaders and clinical staff to embed health play services as a core part of healthcare for all children, and help make the NHS as welcoming, gentle, and child-friendly as possible.

Cathy Gilman, CEO, Starlight

Duncan Burton, Chief Nursing Officer for England

Introduction

What are these guidelines about?

They are about play services in children’s healthcare. Specifically, they are about commissioning, designing and delivering therapeutic health play services that help ensure babies, children and young people have better experiences and improved outcomes from their treatment and care.

Who should read them?

Commissioners, healthcare professionals, and providers of NHS or local authority healthcare services in England.

They are also relevant to non-clinical staff who come into contact with young patients, as well as to children using healthcare services, their families, carers, and the wider public.

Why are they needed?

There is growing evidence of the impacts of serious illness and treatment on children’s mental health – and of therapeutic play’s role in mitigating these risks. At the same time, the value of play in supporting children’s health, wellbeing and resilience has gained increasing attention in both research and policy.

Children tell researchers that hospitals are scary, isolating places, that procedures can be highly traumatic, and that health play staff can make the biggest difference. Therapeutic play opportunities delivered by well-organised teams can help normalise otherwise strange and frightening experiences. Registered health play specialists, integrated within multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), help children to cope with difficult and painful procedures, thereby mitigating the risks of trauma and encouraging positive long-term engagement with healthcare staff and settings.

There is also emerging evidence of the economic benefit of children being less anxious and more engaged in their treatment, with shorter procedures, quicker recovery times and a reduced reliance on sedation and anaesthesia.

Despite these benefits, there is variation in the commissioning and use of health play services across England. Insufficient numbers of play staff and a lack of understanding about their role can prevent children from getting the support they need, leaving them at greater risk of avoidable psychological harm and trauma during their care and treatment.

These guidelines aim to improve access to high-quality, fully integrated health play services across paediatric healthcare and support the delivery of a wide range of play opportunities and clinical support tailored to each child’s setting and clinical need. Ultimately, we want to give more children greater agency in their care, improve their experiences, and reduce psychological harm.

Our use of language

Therapeutic play vs. play therapy

The guidelines are intended to aid the commissioning of health play services providing therapeutic play to children in paediatric care.

‘Therapeutic play’ is supported by health play specialists – also known as healthcare play specialists or play specialists – and is distinct from ‘play therapy’, which is a form of counselling (through play) offered by mental health professionals who are registered play therapists.

These guidelines are not intended to aid the commissioning of play therapy, which may be part of psychological services. See appendix C for more information about this distinction.

Children

The term ‘children’ is used throughout this guidance to refer to babies, children, and young people from birth to age 17. It’s important to recognise that babies, older children, and teenagers in healthcare have play needs, just like toddlers and primary school-aged children. These guidelines are for health play services designed to meet the needs of this full age range.

The role of play in children’s health and healthcare

Play and children’s health and wellbeing

There is substantial and growing evidence of the role of play in children’s health and wellbeing.

Playing provides children with vital developmental opportunities and is key to their early learning and physical competence. It is a primary medium for children’s communication and helps them both to understand, regulate and express their emotions and to experience degrees of autonomy and control. It is fundamental to children’s enjoyment of life and vital to their resilience.

Potential negative impacts of hospitalisation and treatment

A variety of stressors related to illness and its treatment can put children at risk of developing diagnosable mental health conditions. Coming into hospital can be a frightening experience, eliciting feelings of anxiety about the unknown and fear of painful procedures. Children’s psychological experiences of medical treatment range from feelings of temporary, mild anxiety to clinical post-traumatic stress disorder. This can endure and impair a child’s trust as they grow into adulthood, leading to a lifelong aversion to healthcare and healthcare professionals.

Children’s voices, agency and advocacy

Playing is often the primary means by which children express how they are feeling and what they need. A key role of health play staff is to support children’s agency: listening to, communicating with, and engaging with them in the ways they feel most comfortable with. This enables the play team to effectively advocate for children with other health professionals and service managers. People who lead experience of care work and members of the multi-disciplinary team should routinely consult with the play team and involve them in care planning meetings.

Health play services

Health play services should be seen as integral to paediatric care, supporting children through their health journeys by normalising their experiences, helping them to cope with difficult procedures, reducing anxiety and isolation, and mitigating the risks of trauma.

Play service policy and standard operating procedures

The play service should have a clear and transparent policy setting out its purpose and scope – and what children and families should be able to expect from it.

Where adopted, this policy should refer to the Play well standards. Accessible versions of the play service policy and standards should be made available to patients and their families. Some settings may have standard operating procedures for the play service, which serve as an effective play policy. Where this is the case, the production of an overview that is accessible to patients and families should also be considered.

Case Study: helping children switch from liquid medication to tablets

The Leeds ‘Liq2Tab’ campaign

The Play Team at Leeds Children’s Hospital created play-based workshops to help children and young people transition from liquid medications to tablets. The programme was piloted with 13 renal and liver patients, aged 3 and over, who were on long-term medication. In 3 months, with regular 1-to-1 sessions, all of the children made the switch from expensive and difficult-to-store liquids to tablets. This saved the trust an estimated £10,000 a year (for just 13 patients). The team is now running a weekly tablet-taking workshop with a dedicated health play specialist.

Play literacy in multi-disciplinary teams

Multi-disciplinary paediatric teams should have basic training in the principles of health play practice. They should encourage children to play and adopt playful approaches to communicating, treating, and supporting children. All multi-disciplinary team members should know how to refer children and families to the health play service (or a local community play team) and make such referrals as appropriate.

The play team

Health play staff are trained in using therapeutic play to:

- ease children’s anxiety

- prepare children for and distract them during procedures

- advocate for them with other health professionals

- support children’s agency in their own care and treatment

Because some of the highest risks of distress and potential trauma to children are during medical procedures, health play staff should be considered an essential element of the clinical support within the multi-disciplinary team.

The play team will assess the play needs of each child, according to: age and developmental stage; diagnosis; type and degree of any impairments; ethnicity and culture; and, especially, how they engage with the team. For certain patient groups, a bespoke play programme – including proposed interventions before, during and after procedures – may be drawn up. This should be included in the care plan.

Play teams engage with children at a level that allows trust and understanding to be established. This facilitates communication and naturalistic observations of children in healthcare settings. They should be considered as advocates for children and be listened to and responded to by multidisciplinary teams, clinical staff, and consultants.

See appendix A for more information about play team roles.

The need for collaboration

Because of the increase in the numbers of children experiencing mental health problems, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a growing need across healthcare for play therapy and other forms of specialised psychological support for children.

Being treated with compassion and respect can improve the experience of children admitted to acute wards for mental health reasons and influence how they engage with services in the future. Health play teams have an important role here. However, although the use of therapeutic play can be effective in reducing stress and mitigating trauma for children with mental health needs in acute and emergency care, play specialists are not qualified to provide play therapy or clinical psychological interventions (see appendix C for more on the distinction between ‘therapeutic play’ and ‘play therapy’). Collaboration with, and appropriate systems of referral to, the psychology team should therefore be an important part of service design and delivery.

The health play service

The scope of the service

Because the role of play staff is to support children throughout their healthcare journeys, the scope of the play service should encompass all inpatient and outpatient services for children, including acute, specialist, emergency, community, primary, palliative, and end-of-life care settings.

Integrated play service model

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends a personalised approach to improving the experience of healthcare for children who “may have medical conditions that need frequent interactions, inpatient stays and an ongoing healthcare relationship with professionals.”

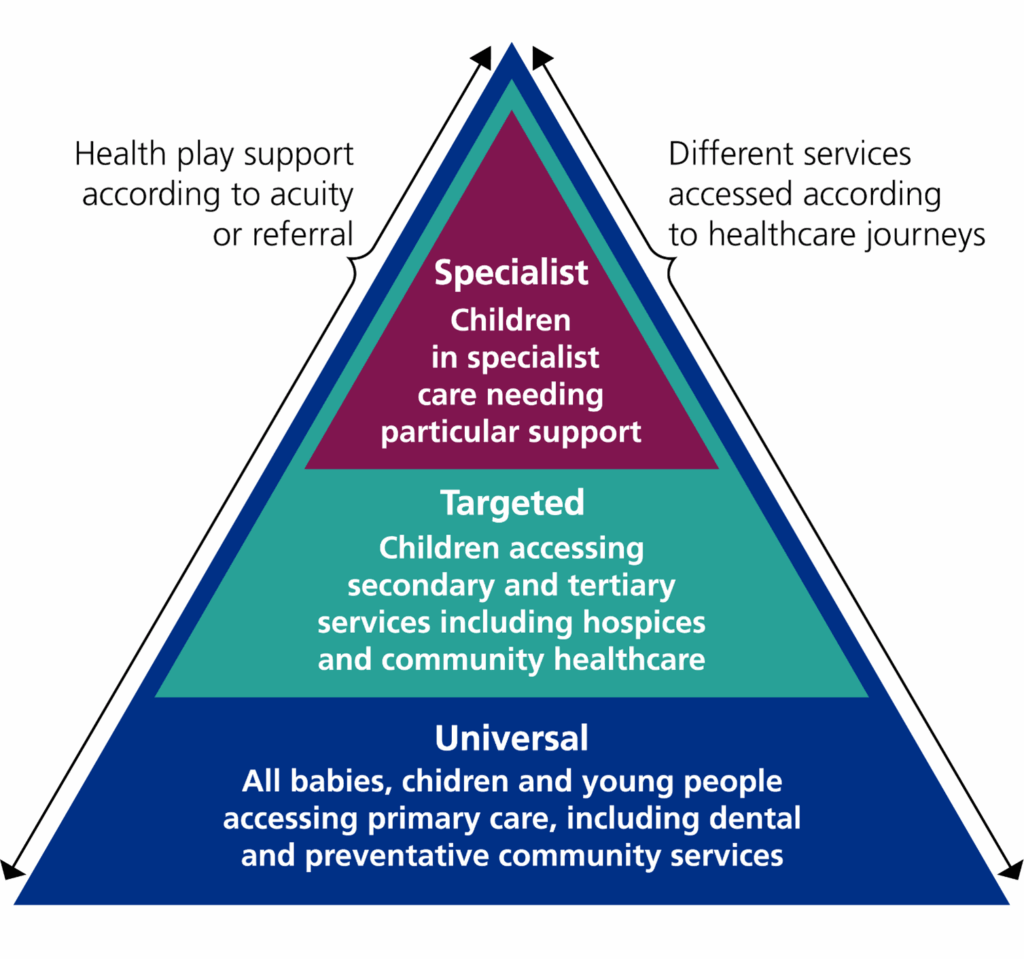

It will help modelling, planning, and delivery to frame health play services within the NHS comprehensive model for personalised care. An integrated model for health play provision will have universal, targeted and specialist interventions based on the level of need, as table 1 below shows.

At the universal level, playful environments and play resources might make community and preventative health services more accessible to children. While specialist services provide individualised play support for children undergoing clinical procedures.

Figure 1: An integrated model for health play provision

Children will have different types of play provision depending on their needs.

These different levels of play provision (specialist, targeted and universal) will have different types of intervention associated with them – and different outcomes.

Table 1: An integrated model for health play provision

|

Level of intervention |

The children it applies to: |

The types of intervention: |

The outcomes:

|

|

Specialist |

Children in specialist care needing particular support |

Play-based interventions and clinical support |

|

|

Targeted |

Children accessing secondary and tertiary services including hospices and community healthcare |

Play sessions and playful engagement |

|

|

Universal |

All babies and children and young people accessing primary care, including dental and preventative community services |

Play opportunities within child-friendly community health services |

|

Specialist

Children facing difficult or complex procedures should be supported by registered health play specialists and bespoke therapeutic play. Play team interventions can help deliver clinically led improvement and support the Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) programme’s core aim of putting patients at the centre of care. For example, some trusts have reduced the number of children needing general anaesthetic for MRI scans by introducing play specialists.

Targeted

Play services should be part of all children’s secondary and tertiary paediatric care, including in hospices and community health settings. Regular play sessions and active play team involvement should be built into each child’s care plan.

Universal

All children need play and have a right to it. It should be integrated into all community provision affecting or involving children. Primary and public health initiatives such as vaccination programmes should engage with health play teams. Primary care providers should consider incorporating access to local play projects and play spaces as an option within personalised care prescriptions.

Case study: reducing the use of general anaesthetics in paediatric MRI

A play-led approach at North Devon Hospital

The play specialist and radiology teams at North Devon Hospital introduced a new approach to paediatric MRI screening. Instead of using general anaesthetics for MRI scans, children and their families are invited to visit the scanner room and receive support from play specialists before their scans. The number of children having their MRIs at the trust without general anaesthetics has increased – and the number of younger children has doubled.

Friends and Family surveys and other feedback highlights a significantly improved experience for children and families and staff now have a better understanding of each other’s roles. There’s also been a cost saving: 99 children were scanned without general anaesthetics in a year, reducing specialist unit bed days and delivering a cost saving of about £49,000.

Design of the play service

The specific design, size and makeup of the play service should be based on an assessment of local context, priorities, and other factors. These will vary according to the type of setting but should include:

- population data

- assessment of the general need for support from the play team

- the composition and capacity of the existing play team (if any) and the wider multi-disciplinary team

- the experience and training and development needs of the existing play team

- the type of healthcare environment and its potential impact on children (please refer to the 15 steps assessment tool)

- the general level of acuity of patients’ needs

Assessment of acuity and need

The assessment of acuity should consider the environment children are in, the experiences they are likely to have, and the perceived risk of trauma. The assessment of need for the play service should look at how play opportunities and interventions may contribute to mitigating such risk, enhance children’s experiences of care, and improve outcomes.

Hours and access

Children need to play every day. Those in healthcare settings are likely to need it more. Services should use principles outlined in the National Quality Board’s Safe and effective staffing guidance for children and young people when deciding play service operating hours. The play service should run in line with the wider service’s days of operation, offering play opportunities and playful engagement to all children through regular play sessions and one-to-one contact with play staff, as needed.

The service’s provision of clinical support – including helping children to prepare for, cope with or be distracted during medical procedures – should be aligned with the schedule for relevant procedures.

Emergency departments (ED)

Accident and emergency services are accessed 24 hours a day. Many children accessing these services are at risk of psychological trauma, which can be mitigated by the play team. Service design should ensure that play staff are available to give clinical support when play-based interventions are most likely to be beneficial.

Staffing requirements

As outlined above, healthcare providers should decide the play team capacity they need based on a range of local factors and priorities. The National Quality Board’s Safe and effective staffing guidance for children and young people should be used to determine the team size, structure and skill mix required to deliver an effective service. Staffing levels will vary depending on acuity and other factors. Settings that care for children with complex needs or children facing highly specialised procedures will need more staff per child, while a lower ratio may be required for children accessing community or primary care.

Team composition

The composition of the team should reflect the needs in a setting. Children with acute and complex needs or those receiving highly specialist care may need more clinical support from health play specialists. On the other hand, children with chronic or long-term conditions may have a greater need for daily play sessions and playful engagement with playworkers. Appendix A outlines the range of play staff roles that may form a healthcare play team.

Staff training and development

Play staff should have the same access to training and continuing professional development (CPD) as other clinical support staff and allied health professionals. Mentoring students and taking part in CPD are registration requirements for health play specialists and these should be seen as core elements of the service that are essential for maintaining standards. Services should be designed to ensure there is capacity and availability for training and mentoring.

Insight: play specialists in emergency care

Standard 5 of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health’s (RCPCH’s) Standards for emergency care says “all emergency departments that treat children employ a play specialist”.

According to the RCPCH, the role of a play specialist in emergency care settings includes:

- providing distraction therapy for potentially distressing procedures

- enhancing nursing and medical skills to involve play in the management of procedures in children

- maintenance of a child-catered environment, including advising on safe and appropriate toys and facilities

- supervision of play in the department

- advising on the requirements of children with additional needs

Community provision

Community health play teams should be deployed flexibly to support children and families in community, primary and tertiary settings. These teams should maintain close communication with hospital teams and establish robust referral pathways, enabling consistent access to play support in hospitals, hospices and the community. They should also work with play providers in the wider community – signposting or referring families to local opportunities that help sustain the therapeutic benefits of play at different stages of a child’s health journey.

Case study: supporting children’s vaccinations

Play sessions and resources in sites across North East London

The Starlight Children’s Foundation provided play sessions and play and distraction resources to 8 COVID-19 vaccination sites for the North East London Integrated Care Board (ICB).

The sites included community centres, medical practices, special education schools and family hubs. An estimated 2,500 children and young people were supported through the project.

The evaluation of the project found that providing play sessions and resources before and after receiving a vaccine reduced the proportion of children feeling negative emotions and increased the proportion feeling positive emotions. Feedback from parents and carers, clinical and non-clinical vaccination staff, and the Starlight team indicated that parents also felt positive emotions (for example, relief, relaxation) because their children were supported by the play provision.

Referrals

There should be clear lines of communication and referral arrangements between the play team and the services being used by children, so that timely and appropriate referrals can be made.

Play resources

‘Toys and play resources stimulate and prolong play, allowing the child to discover what they like and what they are good at … supporting their health and promoting the achievement of developmental milestones’ – Royal College of Nursing

Although the support of specialist play staff is the most important element of the play service, resources – toys, games, props, materials, and equipment – are essential for a high standard of play service.

Budget should be allocated for adequate play resources. Starlight has been providing specially curated play resources to the NHS for nearly 30 years. It recommends some generic items as essential and others as optional for a well-equipped play service.

The team should decide what play resources they need, based on the specific needs and circumstances of the children they support. Appendix B provides information about the types of resources that should be considered.

In addition to a well-equipped playroom, the play team must also have access to adequate storage space for play resources. This should include space for bespoke preparation and distraction resources, which will need careful curation and labelling according to the setting and the type of procedures requiring clinical support.

Insight: shortening treatment times by using play resources

An independent evaluation by Pro Bono Economics indicated that play resources can shorten treatment times and reduce the need for sedation – and therefore saving NHS resources.

The study found that ‘Distraction boxes’ and ‘Boost boxes’ – collections of bespoke toys and play resources curated by the Starlight Children’s Foundation for use in clinical support by health play staff – could reduce average treatment time by 6 minutes. The study estimated a potential annual staff cost saving of £2.2 million and further savings of up to £1 million per year from removing the need for sedation in up to 100,000 treatments per year. It concluded the distraction boxes would pay for themselves if only one fifth of these potential savings were realised.

The healthcare environment and play

“Children who spend long periods in hospital should be able to experience activities as close to their home routine as possible. Play, education and the opportunity to socialise with others are essential activities” – Health Building Note 23: hospital accommodation for children and young people

Hospital and other healthcare setting designs should follow child-friendly, ‘playable’ design principles. NHS Estate’s Health Building Note 23 identifies children’s play as one of the essential components for the design of new build hospitals. It says: “Young children…want to feel safe, remain close to the people they love, eat food they like, have a nice area to play in and have opportunities for ‘more things to do while waiting for things to happen”.

Healthcare ‘gateways’ for children

The environments that children may encounter as their first experience of the healthcare system are particularly important: emergency departments, outpatient services, day surgery units, GP surgeries, and paediatric intensive care units (PICUs).

Children accessing these parts of the service will often need a greater level of support to make sense of their experiences, including their first encounters with hospital staff, extended periods of waiting, and a bewildering array of invasive procedures or interventions. They may also be very unwell, seriously injured or experiencing high levels of pain and anxiety, all of which can add to the risk of trauma.

These gateway areas should be designed, as far as possible, to be child-friendly and welcoming. Service design should consider the need for play teams to be available to children in these settings.

Children visiting adult services

Children visiting adult patients frequently or for extended periods need access to play opportunities for their mental health and wellbeing. Adult services should consider how to provide for such children and may want to liaise with the health play team for advice and support.

Outdoor play and green space

Daily access to outdoor green space – and to outdoor play and contact with nature – is an important element of a healthy environment for children. For children in healthcare, that need is particularly acute. Play space for children in the NHS should include accessible outdoor play areas and green spaces, wherever possible.

Health Building Note 23 says: “In a new-build acute general hospital, the children’s unit should be located on the ground floor, with external views and access to green spaces and play areas. Children and their families should be able to access external play areas directly from the children’s unit”.

Quality improvement

Care Quality Commission inspections

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) includes healthcare play provision as an indicator of a setting being safe, effective, caring, responsive, and well-led. The key lines of enquiry recommended for inspection teams include these questions:

- do you have qualified play specialists available in the areas that children and young people will be seen and treated (for example, wards, outpatient clinics, A&E, radiology)?

- are there any areas where children are seen without access to qualified play specialists?

- are play specialists or services available 7 days per week?

Implementing these guidelines and the accompanying recommended standards (see Play well: recommended standards play in healthcare in England and Play well: quality checklist for health play services) will enable services to satisfactorily meet these criteria.

The 15 steps challenge

The 15 steps challenge: quality from a patient’s perspective (children and young people’s toolkit) helps people who lead experience of care work, paediatric service managers, and practitioners to assess the quality of the healthcare environment from the perspective of children. Recent 15 steps assessments should be taken into account when designing or developing the play service.

Who produced these guidelines?

These guidelines and associated tools were commissioned by NHS England and produced by Starlight Children’s Foundation through the Taskforce on Children’s Play in Healthcare and in collaboration with the Society of Health Play Specialists. The taskforce’s executive board included representatives from NHS England, Starlight, the Care Quality Commission, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), Sophie’s Legacy. More than 60 contributors – including health play specialists, children’s nurses, and patient experience leads from across the NHS – helped shape guidance. We’re grateful to the members whose professional knowledge and experience together with their commitment and hard work made this toolkit possible. More information about the work of the taskforce and a full list of taskforce members is available on the Starlight website.

Appendix A: roles in the play team

Health play specialists

A health play specialist (HPS) is a qualified, registered healthcare professional. The most senior health play specialist will generally lead the health play service within their setting, managing health playworkers and other play staff.

Health play specialists occupy a unique role within multi-disciplinary teams. They are trained to recognise and respond to the play needs of children in healthcare settings and to safeguard the emotional, psychological, social and physical wellbeing of children.

Health play specialists use play as a therapeutic tool to help children understand their illness and treatment, and work with other healthcare professionals to prepare children for treatment and support them during difficult procedures.

Health play specialists will often specialise in the clinical areas in which they are based, developing the specific applied skills and resources that offer the most appropriate support in that context. Generic tasks undertaken by health play specialists include:

- managing the play team

- contributing to children’s care plans as part of the multi-disciplinary team

- working with other professionals on the multi-disciplinary team to support cohesive delivery of care plans

- developing and disseminating the service’s play policy

- organising regular play sessions

- engaging with children to talk about their health, illness, diagnoses and treatment; breaking down complex terminology and developing tools to encourage children to better understand their healthcare journeys

- advocating for children within the multi-disciplinary team

- safeguarding children and ensuring awareness of the risks of traumatic restraint during procedures and of appropriate positioning and holding

- preparing children for difficult or invasive procedures

- distracting, comforting and diverting children’s attention during admissions and procedures

- managing the play service’s monitoring and evaluation against standards

- mentoring HPS students

- liaising with professional bodies and other relevant institutions

- representing the play team in internal and external forums and meetings

- liaising with research institutes to develop and deliver action research projects

- liaising with and supporting families; providing spaces and opportunities to accommodate patient and family time within a child-friendly environment

- writing notes to contribute to the monitoring and recording of children’s mental and emotional wellbeing and (for long-stay patients) developmental milestones

- assisting with admission and discharge planning

- contributing to end-of-life care, including support for siblings and other family members

- maintaining a well-stocked and well-equipped playroom and play resources storeroom or cupboard

Depending on the size and experience of the team, the acuity of patients’ needs, and other contextual factors, many of these tasks may be delegated to or shared with the health playworkers in the team (see below). However, registered health play specialists should have overall management of the team and be available for the key clinical support tasks, such as therapeutic play interventions for preparation, distraction, and trauma mitigation during medical procedures.

Registered health play specialists are qualified via a 2-year foundation degree (FdA) or apprenticeship in health play specialism. They should maintain professional registration with the Society of Health Play Specialists (SOHPS), the recognised professional body. This entails undertaking and evidencing appropriate and sufficient continuing professional development (CPD) and reflecting on the impact of current practice.

The role may have different job titles in different contexts, including ‘hospital play specialist’ and ‘community health play specialist’. These differentiated roles are recognised by SOHPS and practitioners are required to maintain equivalent professional registration criteria to health care specialists.

Community health play specialists

A community health play specialist is a registered health play specialist working with children and their families in community and palliative healthcare settings, often as part of the Community Children’s Nurses Service. They work with children who are disabled or have a long-term or life-limiting condition. Referrals may also be accepted for siblings who are experiencing difficulty understanding and dealing with their brother or sister’s illness or death.

Health playworkers

A health playworker is a member of the play team. They should work under the supervision of a registered health play specialist and should have a minimum of a level 3 qualification in playwork or child development, with relevant experience of working with children and families. Job titles for this role have included ‘playworker’ (without the prefix), ‘play assistant’, ‘activity coordinator’ and ‘play leader’. We recommend that ‘health playworker’ is adopted as standard.

Health playworkers have responsibility for the provision of daily play opportunities and, under the supervision of qualified health play specialists, may contribute to the planning of play programmes and the delivery of play sessions tailored to support a child’s mental and emotional wellbeing and development. They are an essential part of the play team, helping children to live as normally as possible within the healthcare environment and help them enjoy the everyday pursuits of childhood as much as their illness or condition allows.

Health playworkers may also provide assistance in the provision of clinical support through therapeutic play and distraction before and during procedures but should not be expected to do so without supervision by a registered health play specialist.

Playwork is a recognised occupation within the wider children’s workforce, with vocational training, higher education pathways and occupational standards. Playwork within the healthcare context requires additional knowledge and skills and, in this sense, all health play practice should be considered specialised. Appropriate training, mentoring and supervision should be provided.

Youth staff

Larger play (or play and youth) services may also employ specialised health youth workers and youth support co-ordinators to support older children and young people by providing age-appropriate environments for recreation and peer support; and to assess, plan, implement and evaluate therapeutic recreational interventions according to need and acuity.

Senior health play specialists

In larger teams, a senior health play specialist may lead several health play specialists while taking on leadership and management as well as core health play specialist responsibilities. The additional duties may include line management of other health play specialists, management and delivery of teaching and support for mentors and students, and more complex clinical support work. Health care specialists should get the support to develop skills that will equip them for senior roles.

Play service managers

In designated children’s hospitals and larger tertiary services, play service managers are employed to lead larger teams. Teams may consist of health playworkers, health play specialists, youth workers and youth support co-ordinators. Play service managers may take on leadership and management tasks, strategic development and advocacy of play friendly services for children within their organisations. They may contribute to safeguarding boards, patient engagement work and quality improvement projects. Some may deliver specialist clinical support of complex services alongside their leadership role.

Research play specialists

Teaching hospitals and other children’s healthcare settings involved in research may appoint research play specialists to provide play activities for children awaiting sessions, to prepare them for research activities, and to contribute to improving research environments and experiences for children and their families.

The Society of Health Play Specialists

The Society of Health Play Specialists (SOHPS) is the professional body for health play professionals, formed from a merger of the National Association of Health Play Specialists (NAHPS) and the Healthcare Play Specialist Education Trust. SOHPS holds the professional code and standards of practice and ethical conduct for registered health play specialists, students, and apprentices, and the public professional register for qualified health play specialists.

Appendix B: recommended resources for health play services

This is not a complete list, but includes examples of useful resources and equipment.

Role play equipment: doctors kit, baby dolls, kitchen, play food, soft sitting corner, kitchen utensils (metal and wooden).

Arts and crafts equipment: pens, pencils, paint, paint pallets, paper, card, glue, tissue paper, pipe cleaners, stickers, glue sticks.

Baby area equipment: play mat, water mat, rattles, rain maker, bead drum, foil, baby gym, mirrors, cot mobiles, black and white pictures.

Teen area: bean bags, comfy chairs, games console, board games, puzzles, books, mindfulness activities, arts and crafts materials (for example, diamond painting).

Trays: plastic trays of different sizes to make activities accessible and easy to move around.

Furniture: low tables and chairs for all sizes.

Communication aids: PECS cards, Makaton or widget symbols, information boards with Makaton or widget included (for example, signs to the toilet, kitchen, playroom including symbols).

Small world play: cars, trains, houses, small people, animals.

Board games and puzzles: games and puzzles for the fullest range of ages and abilities. Varnished wooden puzzles with small handles are good for young children and those with limited dexterity.

Sensory toys: small items such as sensory bottles, mirrors, bead drums, water mats, foil blankets, bubbles. Large items such as an infinity tunnel, projector, sensory trolley, interactive floor.

Play mats: soft, foldable mats to enable play to happen anywhere.

Games consoles: gaming consoles for teenagers and young people provide a distraction tool, as well as a sense of familiarity.

TV: TV, DVDs and streaming services are another useful resource, providing distraction and a feeling of familiarity.

Appendix C: different roles in supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing in healthcare

This appendix explains the different but complementary roles of professionals who support children’s mental health in healthcare settings. These guidelines focus on the commissioning of therapeutic play (section 1 below). Both may be suitable for children receiving acute or emergency care who have mental health needs.

1. Therapeutic play and health play specialists

Therapeutic play, sometimes called ‘therapeutic medical play’, gives children a way to express their feelings, fears, and anxieties and helps them learn ways to cope with things that may be stressful or upsetting.

Therapeutic play is facilitated by registered health play specialists and, in the non-clinical parts of the service, health playworkers. These staff should be embedded throughout children’s acute, primary and community healthcare services.

Play specialists are often in a good position to build trust and rapport with children and their interactions can not only bring joy, calm and emotional release but also help children develop resilience and build emotional management skills.

2. Play therapy and play therapists

The British Association of Play Therapists defines play as “the dynamic process between child and play therapist in which the child explores at his or her own pace and with his or her own agenda those issues, past and current, conscious and unconscious, that are affecting the child’s life in the present”.

It is a form of counselling (through play) that enables children to explore difficult experiences in a safe environment. Play therapy is provided by registered play therapists. These are mental health professionals who may be employed within the paediatric psychology team or as part of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS).

3. Paediatric psychology services

Paediatric psychology services help children and families cope with the psychological aspects of health and illness, such as “anxiety about hospital procedures; coping with pain; trauma following an accident; effects of the illness on family members; stress related symptoms and management of children in hospital”. Paediatric psychology services are delivered by registered clinical psychologists, who may also work with play therapists, child psychotherapists and counsellors.

Appendix D: the policy context for the guidelines

The mission statement of the Children and Young People’s Transformation Programme Board, developed with youth board members, states: “We want all children, young people and families to have their voices embedded at the core of our work as we transform health and care for the better. We will work with everyone who can inspire change to do this”.

The guidelines describe the role of health play services in helping to make this ambition a reality. It sets out how these services should be delivered as a core part of children’s healthcare.

This document is not intended to be used on its own. It should be read alongside existing policies and guidance that inform commissioning decisions and service design. This includes but is not limited to:

The guidelines’ companion publication

- Play well: recommended standards for health play services in England

- Play well: quality checklist for health play services

Key policies and frameworks

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child – outlines children’s rights, including the right to play and to have their views heard.

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child general comment no.17 – focuses on the child’s right to rest, leisure, play and cultural life (Article 31)

- The Care Act 2014 – includes duties around wellbeing and care planning, with implications for children in transition to adult services

- The Health and Care Act 2022 – sets the legal framework for integrated care systems and service delivery

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline: babies, children and young people’s experience of healthcare (NG204) – guidance on improving the experiences of children and young people using health services

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) standards for paediatric care – outlines expectations for safe and effective paediatric services

- Royal College of Nursing guidance for nursing staff – includes recommendations on the role of nurses in safely supporting and promoting play

- Society of Health Play Specialists (SOHPS) professional standards – defines the professional standards and scope of practice for health play specialists

- Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspection framework for hospital services for children and young people – sets out what good care looks like and how services are inspected and rated

About Starlight

Starlight is the national charity for children’s play in healthcare. It supports health professionals using therapeutic play with children to boost their wellbeing and resilience during treatment, care, and recovery from illness. Starlight’s mission is to enable all children in the UK to have their right to play protected and provided for when they are receiving healthcare in or out of hospital. Informed by research into what works best, the charity provides direct services to children and their health play teams; and advocates for the full recognition of children’s play as an integral component of their health and care.

To enquire about support to adopt and implement these guidelines, please email healthplay.services@starlight.org.uk

Publication reference: PRN01936_i