Introduction

The NHS Long Term Plan and the changing commissioning architecture gives us the opportunity to use collective resources within an integrated care system (ICS) to develop a service that supports people to remain independent, safe and in their own homes for as long as possible. Development of services including virtual wards should be a continuum of care through collaboration, supporting both a proactive and reactive approach to delivering care in a joined-up way. We also have the opportunity through using population health intelligence, personalised care and digital inclusion to ensure that the outcomes for patients reduce health inequalities and do not widen them.

A virtual ward is a safe and efficient alternative to NHS bedded care that is enabled by technology. Virtual wards, including hospital at home, support patients who would otherwise be in hospital to receive the acute care, monitoring and treatment they need in their own home or place of residence. This includes allowing the patient to be cared for in their own home initially or to go home sooner. We know that patients who are supported through an acute illness are able to recover better in their own homes, with less chance of deconditioning and more chance of staying connected to their carers and communities, and have better outcomes and less reliance on long-term care options (Singh et al 2022).

This guidance supports ICS clinical leadership to create and develop their virtual ward service. It acts as a starting point for development and provides some core clinical considerations for further development to achieve a mature virtual ward offer. It sets out how virtual wards should be developed with providers, co-produced with local people, and given knowledge about their population’s health need and local resources within the community. This document should be read in conjunction with Supporting information: virtual ward including hospital at home and guidance notes for virtual ward pathways: acute respiratory infection virtual wards and frailty virtual wards (hospital at home for those living with frailty). There is also a guide to setting up technology-enabled virtual wards.

Some services will offer a blended approach with aspects of technology enablement including remote monitoring and face-to-face care that best fits the clinical need of the patient groups being cared for in a virtual ward. It is important that the virtual ward offers a personalised care and digitally inclusive approach that meets an individual’s needs, offering the most appropriate level of care.

Clinical governance

Overview

Integrated care boards (ICBs) should be working to place effective clinical and professional leadership at the heart of the ICS. This includes ensuring professional and clinical leaders are fully involved as key decision-makers, with a central role in setting and implementing ICS strategy. The Building strong integrated care systems everywhere ICS implementation guidance on effective clinical and care professional leadership provides two core expectations of an ICB:

- Each ICB is expected to agree a local framework and plan for clinical and care professional leadership with ICS partners and ensure clinical and professional leadership is promoted across the system.

- Individuals in clinical and/or care professional roles on the ICB board, including the nursing director or medical director, should ensure leaders from all clinical and care professions are involved and invested in the vision, purpose and work of the ICS.

ICS clinical leadership and governance should link into relevant local organisational clinical governance structures. These expectations also apply to the development of plans for clinical and care professional leadership with partners across the ICS, as part of establishing their virtual wards.

To provide additional support nationally for the establishment of virtual wards, NHS England will be developing clinical and professional leadership structures at national and regional levels.

Each ICS is expected to establish a clinical reference group (CRG) or similar to support the development of virtual wards across the ICS. An ICS-level CRG should include ICS nursing, allied health professional (AHP), pharmacist, clinical and social care professionals to provide expert advice, along with clinical and professional leadership to support local implementation of a range of virtual ward services.

The virtual ward clinical leadership should also reflect the rich diversity of clinical and care professions across the wider ICS partnership, including health, social care and the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sectors, embedding an inclusive model of leadership at every level of the virtual ward programme.

Where delivered by one organisation, a virtual ward service would exist as a normal part of that organisation’s clinical governance. If the virtual ward service is delivered by a provider collaborative, then the overall accountability for clinical governance would be with the nominated lead provider. There should be an accountable clinical service lead reporting into the medical director and chief nurse of that organisation. These organisational elements should report into or be part of the overall ICS clinical oversight and governance of virtual wards for that system.

The virtual ward service should be supervised by a senior registered clinician with the competencies required to provide the level of care to operate the service acting as accountable senior clinician. This would typically be a consultant or consultant practitioner with the appropriate skills and competencies in acute care working beyond the boundaries of an acute hospital setting. The service lead would report into the medical director, who shall need to be assured of the knowledge, skills and competencies of these accountable senior clinicians. A senior clinical decision-maker is required to make a decision on admission to a virtual ward, working closely with other services to support appropriate and timely access to care within the virtual ward but also with diagnostic and enabling services such as pharmacy, to deliver the right care, at the right time within a home setting where possible.

Patients transferring to a virtual ward would have their care transferred to the lead clinician for the virtual ward, as care would normally be transferred in acute settings.

Out of hours

ICSs must ensure that there are clear, formalised pathways in place to support early recognition of deteriorating symptoms and out-of-hours support to manage deterioration, enabling capacity in existing out-of-hours services, including community night nursing team services or GP out-of-hours service where appropriate. There must always be appropriate escalation processes and services in place to maintain patient safety. This should include providing comprehensive patient information (translations and easy read where appropriate), supported with videos, written and digital resources and links.

This will require the ICS Directory of Services (DoS) to be updated to ensure services available to support virtual wards out of hours are accessible to referring services, alongside appropriate knowledge and skills training to embed the approach locally.

Operating procedures should be in place to ensure support is available out of hours to manage deterioration and maintain patient safety 24 hours a day. In many cases this will involve integration with existing procedures and may involve ICSs reviewing provision and formalising additional provision where demand exists for cohorts of patients with highest needs.

It is recommended that providers ensure a proactive handover process using a structured approach such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation), a technique that can be used to facilitate prompt and appropriate communication and NEWS2 (National Early Warning Scores 2) if appropriate for patient group if there is a concern, supported by access to the updated patient management plan or information available on a shared care record.

Safeguarding

As commissioners of local health services, ICSs need to assure themselves that organisations from which they commission have effective safeguarding arrangements in place. Systems need to demonstrate that their designated experts (for children, children in care and adults) are embedded in the clinical decision-making of the commissioned organisations, with the authority to work within local health and social care economies to influence local thinking and practice and with the capacity to do so. ICSs are required to demonstrate that they have appropriate systems in place for discharging their safeguarding statutory duties. There must be a clear line of accountability for safeguarding, properly reflected in the ICS governance arrangements, ie a named executive lead with overall leadership responsibility for the organisation’s safeguarding arrangements.

Appropriate safeguarding procedures to protect vulnerable patients and/or carers must be in place. Schedule 32 of the NHS Standard Contract lays out the requirements for ensuring providers meet their duty of care in terms of safeguarding; this includes where aspects of the patient pathway are delegated to other providers.

The lead provider must ensure all staff have the correct level of safeguarding training for their role and know how to escalate concerns. Remote monitoring does not preclude these requirements. The NHS Safeguarding team aim to keep staff updated on safeguarding informed practice via the free NHS Safeguarding App (level 1 and 2).

The lead provider requires assurance that third-party providers, including charities, meet the Lampard recommendations for safe recruitment and Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) processes. With the ending of the COVID Act on 31 March 2022 this includes the retrospective process of ensuring staff who revived DBS lite checks have full DBS checks. A list of safeguarding resources can be found on FutureNHS.

Patient safety

In line with the NHS Patient Safety Strategy, the development of virtual wards must match the NHS commitment to continuously improve patient safety. The standards for safety will continue to be refined by new evidence, research and innovations, and this includes for developing safe and effective virtual wards.

When working to develop virtual wards, systems and providers should collaborate to develop a patient safety framework to complement their existing patient safety initiatives laid out in the NHS Patient Safety Strategy, liaising with the dedicated patient safety specialists in their respective organisations.

This includes consideration of the role of technology across pathways and for outcomes as part of the overall clinical safety case. There are specific considerations that a clinical safety officer can advise on, and additional information is available on the NHS England website.

To ensure high quality and safe services, consider the following:

- Any workforce model must align with the National Quality Board safe sustainable and productive staffing and NHS England developing workforce safeguards, which include a full quality impact assessment review as per the Care Quality Commission well-led framework requirements.

- The registered workforce is required to work within their respective professional regulatory standards, code of practice and good medical practice principles; for the social care workforce this relates to safer practice.

- Appropriate clinical leadership, clinical supervision and governance should be in place. Ongoing systematic processes for the monitoring and response to safe staffing indicators, such as nursing red flag events and patient and staff outcomes.

- Core capability-based approach, avoiding assumptions about professional boundaries and early investment in workforce development and training.

For all healthcare professionals there is a legal and professional requirement to hold adequate and appropriate clinical negligence indemnity cover, either through their membership of an NHS scheme via their NHS employer or arranged directly.

In England most providers of NHS services are covered for clinical negligence risks by one of the state indemnity schemes run by NHS Resolution. Further information on indemnity is included in the guidance Supporting information: Virtual ward including hospital at home.

Integrated services

Multidisciplinary teams

A virtual ward should be clinically led by a named registered consultant practitioner, ie doctor, nurse, AHP or GP with knowledge and capabilities in the relevant specialty or model of care (or access to specialist medical advice).

Virtual wards are most effective when delivered by integrated multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) who work beyond the boundaries of an acute hospital setting across secondary, community, primary, mental health and social care. Many virtual ward teams are and will be aligned with other services, such as urgent community response (UCR), same day emergency care (SDEC), community-based nursing teams, integrated urgent care or other virtual care services supported by social care and VCSE services. To support this and provide safe, quality and personalised care, there should be clearly defined roles and responsibilities across the team for both clinical and non-clinical team.

There should be a system-wide approach ensuring collaboration to share workforce skills and expertise in the best interests of system-wide change. For example, ensuring senior clinicians and pharmacists are available to provide expert clinical support and pharmacy reviews. There should also be support services in social care and voluntary services, e.g. night sitters, delivering medications.

Commissioners and providers should ensure that they have the appropriate workforce and skill mix in place to deliver virtual wards and meet their local population needs, and that teams have access to appropriate skills, training, tools, equipment and support. They should also support inclusion of newly qualified professionals and students.

Admission and discharge

While working as part of integrated teams benefits the management of patients, it is important that virtual ward services are a legitimate substitute for a secondary care bed as per the definition of a virtual ward. There must be clear admission and discharge criteria that are appropriate to the acute level care being provided and supported by all key partners across the virtual ward pathway.

Referral in

A senior clinical decision-maker should decide whether the person is admitted to a virtual ward. This should be based on the same level of clinical assessment and decision-making as if the patient were being admitted to a hospital bed. This may be made in consultation with other specialty clinicians.

This is a shared decision-making process with the patient (with capacity) and where relevant with their carer (with best interests or power of attorney for health). The patient and/or carer must consent to admission, with a full awareness of the benefits and risk (which may be supported by specific patient information material).

This process should be clearly documented along with clear escalation plan and ReSPECT documents if appropriate.

The senior clinical decision-maker requires access to a range of expertise, equipment, and services, such as MDT members with advanced assessment skills and access to point of care diagnostics, or SDEC or similar services to support their decision.

The senior clinical decision-maker has the option to direct patients to other services, eg UCR, SDEC or primary care, and therefore should have a wide understanding of all options available. This decision should be reviewed at regular intervals during the time that the patient stays on the virtual ward.

Referrals will come from a range of services, including 111,999, emergency departments and SDEC or through community or general practice referral routes. There is a big opportunity to develop pathways that support admission avoidance by using virtual wards and hospital at home.

The following actions will support providers increasing referrals from the key sources outlined above. Further steps will likely be needed to ensure a streamlined referral process is developed.

- Collaborative working with other providers, ICS leads and commissioners to develop local referral processes to support local continuums of care across services. This will also include care home leads, NHS England regional virtual ward teams, UCR including integrated care, urgent care, SDEC, NHS111 providers, primary care and local ambulance trusts.

- Ensure that all providers have access to the local shared care records, including independent providers where they are commissioned to support delivery of care for virtual wards.

- Interoperable digital systems to enable the seamless transfer of information between clinicians, services and organisations, and referral and onward delivery of care.

- The sharing of service information, including case studies, to help referring clinicians understand virtual ward capability and which patients are appropriate to refer.

- Support awareness of virtual wards locally and not only through adding virtual wards to the DoS, supported by commissioners against core criteria, but also through supporting referring partners with regular knowledge and skills training to ensure that they confidently understand the local virtual ward service and agreed referral routes.

In line with best practice, some services find it beneficial to use trusted assessment principles both within and across teams and organisations, e.g. in an acute provider, to facilitate supported discharge from wards or urgent care units. These enable another professional’s judgement to determine that a virtual ward admission is necessary and for the service to respond. This requires a common understanding of virtual ward service capability and can help to reduce the need for repeated assessments and provide a seamless service.

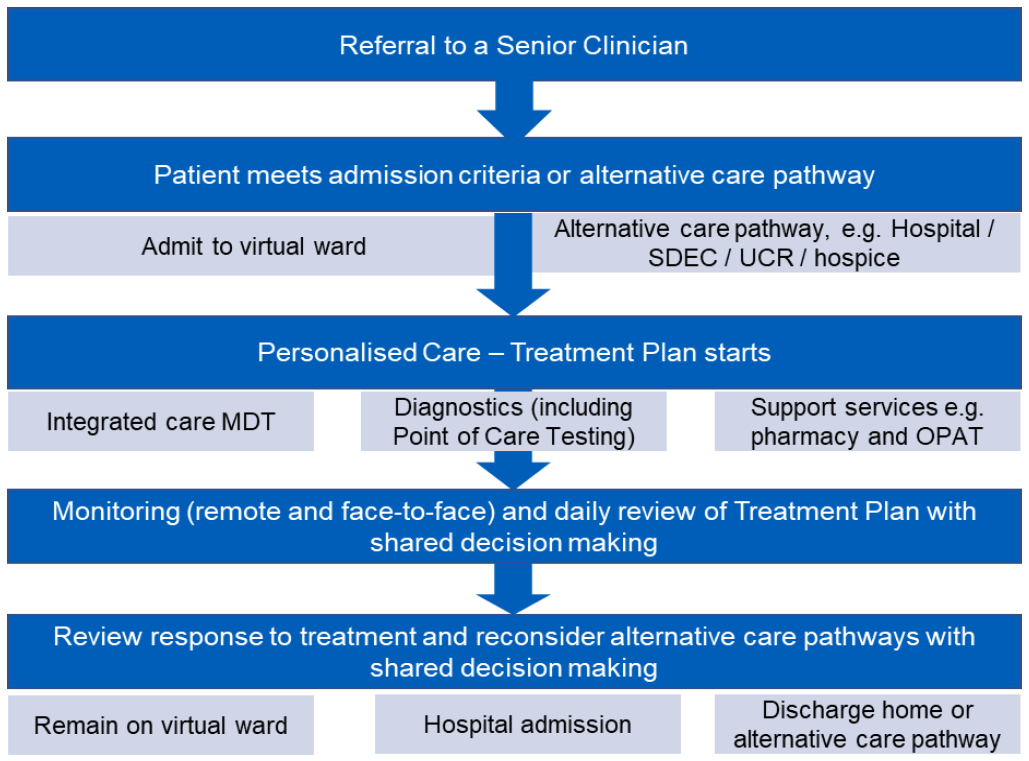

Figure 1: Patient clinical review pathway in a virtual ward

Image text:

- Referral to a senior clinician

- Patient meets admission criteria or alternative care pathway

- Admit to virtual ward / alternative care pathway eg hospital / same day emergency care (SDEC) / urgent community response (UCR) / hospice

- Personalised care treatment plan starts

- Integrated care multidisciplinary team (MDT) / diagnostics (including point of care testing) / support services eg pharmacy and out-patient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT)

- Monitoring (remote and face-to-face) and daily review of treatment plan with shared decisions making

- Review response to treatment and reconsider alternative care pathways with shared decisions making

- Remain on virtual ward / hospital admission / discharge home or alternative care pathway

Admission criteria

Admission criteria should be developed by clinicians and reflect the need of the local population. This should consider a patient’s preference for where their care should take place. ICS urgent and emergency care boards should review the admission criteria and whether the virtual ward is supporting the health needs of its population at a place or primary care network level. The board may wish to understand the rates of admission from the virtual ward to acute care and develop admission criteria appropriate to the level of acuity of patients. Their remit may also be expanded to encompass assessment of patients who deteriorate in community settings.

Discharge criteria

The discharge criteria from acute level virtual wards should be in line with acute hospital discharge criteria. Virtual wards are time-limited interventions and patients must be discharged when they no longer need this level of care. The senior clinical decision-maker must clinically assess if the patient is fit for discharge in line with local acute discharge criteria and the MDT should work towards an estimated date of discharge for the patient.

Central to the delivery of effective and timely discharge is planning by professionals within the team, clinical oversight, effective communication and criteria-lead discharge. This is underpinned by regular reviews of the treatment and care, ensuring a consistent focus on the principles of personalised care.

As with all acute care, a regular/daily review of every person on the virtual ward to make decisions is essential for avoiding delays and improving outcomes for patients. Suitable arrangement to transfer care from the virtual ward to alternative pathways suitable for a person’s care needs should be made in line with Hospital discharge and community support: policy and operating model pathways guidance.

Patients should be discharged and care should be transferred to the relevant primary, community or social care-led services, including:

- primary care provider/GP

- discharge to assess service

- community nursing team/rehabilitation

- intermediate care service

- end of life care, community or hospice

- specialist community teams.

It is important to avoid discharges that are unsafe, e.g. happening without adequate handover of care or support or lead to people not being fully informed as to the next stages of their care.

Where relevant, if a comprehensive geriatric assessment or any other assessment has commenced, this must be clearly communicated to services taking over a person’s care and completed in a timely and joined-up way. It is important that medication changes are appropriately communicated and adjusted as required, with a focus on not disrupting usual patient supplies and oversupply.

When developing services in the transition of care between virtual ward services and end of life services, clear pathways must be agreed between services and appropriate care planning to ensure high quality end of life care.

Personalised care

When developing virtual ward clinical pathways, it is important that systems build in a personalised care approach based on what matters to people and their individual strengths and needs. This should include shared decision-making when deciding a plan for current and future treatment. This is especially important when developing virtual ward services where a significant proportion of people with long-term conditions and/or frailty will require supportive care post discharge from a virtual ward service.

It is expected that where a proactive service (e.g. enhanced health in care homes or anticipatory care) has identified a personalised care and support plan that this shall be available to the virtual ward service. This plan shall provide important information around an individual’s wishes, supporting the shared decision-making process.

The shared decision-making process should be used when clinicians discuss and decide with individuals what tests, treatments or support packages are most suitable, bearing in mind the person’s own circumstances. It brings the individual’s expertise about themselves and what is important to them together with the clinician’s knowledge about the benefits and risks of the treatment options available. Lay expertise is given the same value as clinical expertise.

The person and/or their family should work in partnership with their health and social care professionals to complete this assessment, which then leads to producing an agreed personalised care and support plan.

Third sector groups, carers and carer groups should be involved early in the design of virtual wards, the technology to be used and what support and care will be offered. More information to support carers and mitigate any potential risk that virtual wards mean unpaid carers will be asked to pick up more caring responsibilities can be found in the Supporting information for ICS leads: Enablers for success: virtual wards including hospital at home.

Co-production

Co-production with clinicians and experts by experience should also be at the heart of virtual ward commissioning and service design. This involves working in partnership with VCSE organisations. Co-production means service users, carers and staff working together to develop and shape services, rather than staff making decisions alone. To provide truly effective virtual ward services, there needs to be equal partnerships between users and providers of a service. It encourages transparency about how and why things are done, providing confidence that services provide the care people need.

Hospital admission

The care plan for a patient on a virtual ward shall be constantly under review with the senior registered clinician overseeing the response to treatment. This would be shared with the patient and shared decisions made about the continued management within the virtual ward setting or escalation to another setting such as a hospital or hospice if required.

The hospital admission rate should be reviewed based on patient need and should not be a reporting metric that is used to measure performance in isolation. It should be evaluated by the service provider(s) on a regular basis to ensure that this benchmarks well with other similar services and that the admission criteria for the service are safe and correct.

End of life care and advance care planning

Palliative and end of life care is underpinned by close partnership working across health and social care, and through integrated community teams. There are regional and system differences in the way palliative and end of life care services are developed and delivered. Wherever possible, virtual wards should be developed and/or delivered in partnership with commissioners and other providers, including the voluntary sector and social care, to support end of life care and good advance care planning using the Universal principles for advance care planning.

There should be a system approach, ensuring collaboration to share workforce skills and expertise in the best interests of system-wide change. A system approach enables other virtual wards (eg frailty) and other urgent care programmes (eg UCR) to be part of an integrated approach as patients with end of life needs often overlap with those requiring support from virtual wards, UCR and acute services.

Outcome focused care

The performance of virtual ward services must be measurable, visible and accountable. Data capture should be standardised across whole systems to facilitate quality improvement and provide assurance that the service is providing improved person-centred outcomes and staff experience with effective use of resources. Agreeing patient outcomes early will assist with developing the workforce model and safety and quality metrics.

We would expect that ICSs link data directly from providers at a patient level to evaluate the service. This should link into population health management intelligence to support local evaluation. It is important that this data is used to compare outcomes and monitor against local health inequalities and digital inclusion measures with consideration at an ICS and place level.

The accurate collection, recording and reporting of data are critically important for ensuring that people are benefiting from effective virtual wards.

Implementing a set of standard metrics for measuring performance and outcomes will assist better management of the needs and outcomes of virtual ward patients. Understanding the effectiveness of system performance is key to understanding the co-dependencies between services.

Information governance

Information sharing is essential for providing safe and effective care, with all health and care organisations having a responsibility to ensure that information is handled appropriately across partnership organisations. Adhering to The eight Caldicott principles, ICSs need to ensure that information governance guidance, policies and procedures are in place across provider collaboratives delivering virtual ward services.

NHS England has developed guidance and frameworks to support local implementation of good information governance practice:

- Guidance to support virtual ward information governance

- How health and care information should be accessed and managed: Information governance framework for integrated health and care: Part 1 – Shared care records.

Publication reference: PR1480