About this guidance

This guidance has been developed by NHS England with the following partners:

- Care Quality Commission

- Centre for Governance and Scrutiny

- Department of Health and Social Care

- Healthwatch England

- Local Government Association

- National Voices

- NHS Confederation

- NHS Providers

- Patients Association

- The Health Creation Alliance

- Integrated Care Systems in Dorset, North East and North Cumbria, Sussex and West Yorkshire.

It also had input from NHS England’s public participation networks and forums. NHS England undertook a public consultation on this guidance during May 2022.

This statutory guidance is made up of a suite of documents – the main body and two annexes:

- Guidance on working with people and communities: this sets out how the guidance should be used; the main legal duties; reasons for working with people and communities; and the leadership needed to realise these benefits. It gives 10 principles to follow to build effective partnerships with people and communities.

- Annex A gives the detail on putting it into practice. It describes the approaches to take for different contexts and how organisations can work together to create genuine and authentic relationships with local communities.

- Annex B explains the public involvement legal duties in more detail and organisations’ responsibilities for working with people and communities.

Further information about all the case studies can be found on the NHS England website. It links to other relevant guidance on integrated care and to further resources on working effectively with people and communities.

Forewords

Edward Argar, Minister of State for Health

People and communities are at the heart of everything the NHS does. Working with people and communities is critical if we are to create a health and care service which offers personalised care, is tailored to the needs of each individual, and which works for everyone.

The Health and Care Act 2022 is designed to enable a more joined up, collaborative system. System leaders from across health and local government told us they wanted to work better together to tackle the big challenges in health and care. The Act ensures that every part of England is covered by an Integrated Care System, which brings together NHS, Local Government and wider system partners to empower them to put collaboration and partnership at the heart of planning. To achieve real impact, we need systems to look beyond those who are typically involved – building partnerships across traditional boundaries and working with people, communities and those who represent them to create real change.

The Act also introduces a new duty on NHS organisations to have regard to the effects of their decisions on the ‘Triple Aim’ of the health and wellbeing for the people of England, quality of services provided or arranged by NHS bodies, and sustainable use of NHS resources. The previous legislative framework directed organisations to work primarily in the best interest of their own organisations and their own immediate patients – but this does not fully support the delivery of integrated, patient-centred care. The new duty requires organisations to think about the interests of the wider system and provides common, system-wide goals that need to be achieved through collaboration. We expect NHS organisations to draw on the knowledge and experience of wider partners, including the voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector, local authorities and Healthwatch, alongside their communities when considering how to meet this duty.

By working with people across places, we can better tailor services to meet their needs and preferences, so that they are designed and delivered more effectively. This ensures that locations, opening times, models of care, and patient information are suitable for the communities we serve. Involvement helps us prioritise resources to have the greatest impact; and helps us make better decisions about changing services. Information from involvement activities can be used alongside financial or clinical information to ensure that services are delivered in a way that works for patients and their carers, and can be tailored to the needs of a particular area.

This guidance has been developed in partnership with organisations with experience of working with communities and ensuring their voices are heard in health and care services. It is intended to support health and care systems to build positive and enduring partnerships with people and communities in order to improve services and outcomes for everyone. It is an important next step in realising the benefits of the changes brought about by the Health and Care Act 2022.

Amanda Pritchard, Chief Executive, NHS England

The NHS has always been at the heart of communities. Our hospitals, primary care and community health services provide services to millions of people every week, and a reassuring physical and psychological presence for many more. And never has the NHS been a source of more reassurance and more pride for communities than during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The NHS response to the pandemic – both the initial efforts to protect people from the virus, and especially our delivery of the vaccine programme – has depended in large part on our ability to work with and through communities, not just to spread broadcast messages, but more importantly to understand and overcome barriers to accessing services.

As we move into a new phase, our mission now is to continue recovery and tackle Covid backlogs, reform for the future and build resilience to future pressures. But we must also do so with respect for our patients and communities, ensuring their needs and opinions are central to how we plan, deliver and improve services.

Through Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) – particularly now they are underpinned by statutory Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) and Integrated Care Partnerships (ICPs) – we have an opportunity to further strengthen the relationship with the communities we serve collaboratively, with our Local Government and Voluntary Sector partners. The involvement of our people and communities sits right at the heart of this relationship; we can’t achieve the best outcomes in the most effective way, without working with the people we treat and care for.

The public rightly have high expectations of the NHS. But equally they understand the challenges we face, and want ways to be involved in finding solutions. They have knowledge, skills, experiences and ideas to develop solutions that best meet their needs and support their health and wellbeing. Without insight from people who use, or may use, services, it is impossible to make truly informed decisions about service design, delivery and improvement.

This is particularly important in addressing the health inequalities highlighted by the pandemic; we need to take this opportunity to address the barriers and challenges people experience and ensure we improve the health and wellbeing of the people who need care and support the most. And sometimes this means having the courage to be challenged on our current and historic performance.

Fortunately, we are not starting from scratch. As this guidance sets out, we can build on examples of existing collaboration already taking place in ICSs and on the benefits we have already seen and are seeing from working with communities this way.

Sam Allen, Chief Executive, North East & North Cumbria Integrated Care Board

Listening and involving the communities and citizens we serve through open conversations, to truly make a difference together, and with the aim of reducing inequalities is at the heart of our Integrated Care System. People and communities are why we are here, and we are in service to them. We will draw on their lived experience, wisdom and expertise and involve them as partners in our work.

Adam Doyle, Chief Executive, Sussex Integrated Care Board

I am very pleased to support the guidance for all ICBs and ICSs. The communities that we serve are best placed to help shape and co-produce health and care services that are meaningful to them. I encourage all colleagues to consider this guidance in as they take forward their 5-year strategy in each of their systems.

Patricia Miller, Chief Executive, Dorset Integrated Care Board

I am very privileged to confirm my support for a new approach to involving communities. If we are going to fulfil the ambition of integrated care systems around reducing inequalities, we need to understand the lived experience of our communities and design solutions with them that enable them to live their best lives and thrive. Our citizens should be at the centre of every decision we take.

Kate Shields, Chief Executive, Cornwall Integrated Care Board

Our view about person voice is really clear. Without the voices of our people and our communities we will fail from the start. What we do and how we do it has to be aligned with what matters to the people we serve.

People and their communities will increasingly be engaged in our services re-design across our system and we’ll ensure their voice is heard in our ICB and be at the heart what we do in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly.

Executive summary

The Health and Care Act 2022 mobilises partners within Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) to work together to improve physical and mental health outcomes. These new partnerships between the NHS, social care, local authorities and other organisations will only build better and more sustainable approaches if they are informed by the needs, experiences and aspirations of the people and communities they serve.

This is statutory guidance for Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), NHS trusts and foundation trusts, and is adopted as policy by NHS England. It supports them to meet their public involvement legal duties and the new ‘triple aim’ of better health and wellbeing, improved quality of services and the sustainable use of resources. It is relevant to other health and care organisations, including local government, to ensure that we work collaboratively to involve people and communities, in ways that are meaningful, trusted and lead to improvement.

The public involvement legal duties require arrangements to secure that people are ‘involved’, and this can be in a variety of ways. ICBs, trusts and NHS England need to be able to demonstrate that they assess whether that the duties apply to decisions about services and, where they do, that they are properly followed. NHS England’s assessment of ICBs’ performance will include how they meet their legal duties. There are also policy requirements for Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), Integrated Care Partnerships (ICPs), place-based partnerships and provider collaboratives to involve people, including in their membership and when developing plans and strategies. Involvement is a contractual responsibility for Provider organisations, including General Practice, as set out in the NHS Standard Contract.

While involving people and communities is a legal requirement, working with them also supports the wider objectives of integration including population health management, personalisation of care and support, addressing health inequalities and improving quality. The legal duties provide a platform to build collaborative and meaningful partnerships that start with people and focus on what really matters to our communities. However, the ambition is for health and care systems to build positive, trusted and enduring relationships with communities in order to improve services, support and outcomes for people.

There are clear benefits to working in partnership with people and communities. It means better decisions about service changes and how money is spent. It reduces risks of legal challenges and improves safety, experience and performance. It helps address health inequalities by understanding communities’ needs and developing solutions with them. It is about shaping a sustainable future for the NHS that meets people’s needs and aspirations.

Senior leaders have a particular role in making this happen. They should ensure that they:

- understand and act on what matters to people

- demonstrate how their organisations meet met the legal duties to involve

- work with partners to put people are at the centre of everything they do

- ensure there are resources for their organisations to do this work effectively

- spend time personally listening to and understanding their local communities.

Accessible diagram text:

The 10 principles for working with people and communities are:

- Centre decision-making and governance around the voices of people and communities

- Involve people and communities at every stage and feed back to them about how it has influenced activities and decisions

- Understand your community’s needs, experiences, ideas and aspirations for health and care, using engagement to find out if change is working

- Build relationships based on trust, especially with marginalised groups and those affected by health inequalities

- Work with Healthwatch and the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector

- Provide clear and accessible public information

- Use community-centred approaches that empower people and communities, making connections what works already

- Have a range of ways for people and communities to take part in health and care services

- Tackle system priorities and service reconfiguration in partnership with people and communities

- Learn from what works and build on the assets of all health and care partners – networks, relationships and activity in local places.

This guidance is structured around 10 principles. These have been developed from good practice already taking place, and will help organisations achieve the benefits of effective working with people and communities:

Applying the principles means taking a variety of approaches to working with people and communities, depending on context and objectives. Regardless of the approach used, organisations should start with existing insight about the needs and experiences of their communities, and work with partners that already have links to them. They should also consider taking community-centred approaches – ones that recognise the strengths within communities and that build on existing assets that support people’s health.

To ensure legal duties are met, all approaches should be fair, proportionate and have regard to equalities, so that all relevant groups can take part. They should be designed to take account of the contexts that people live their lives in. This means building trust, safety, and shared understanding.

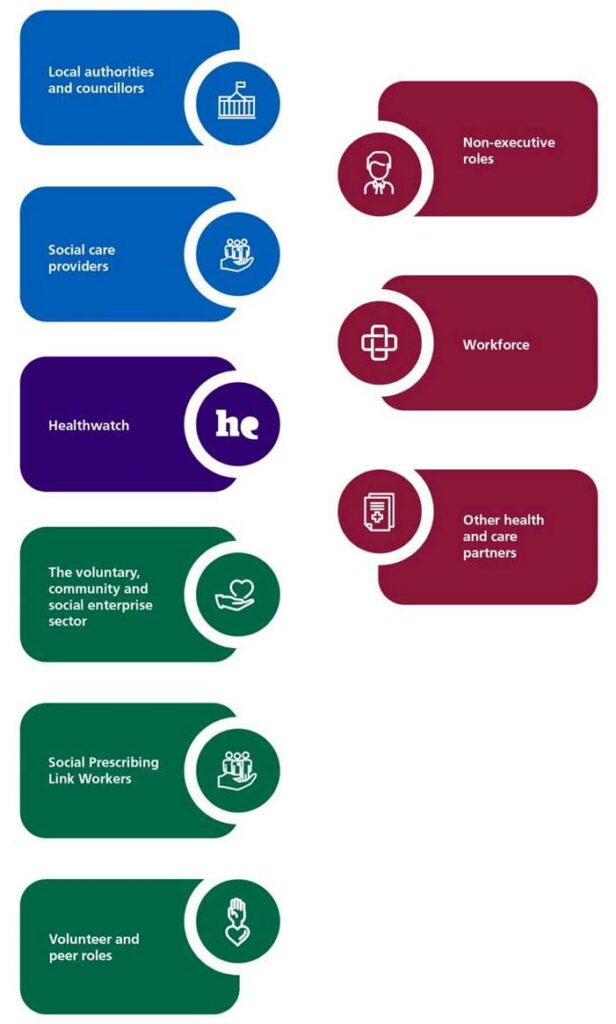

Integrated care gives an opportunity for the NHS to collaborate with partners on working with communities. This is both within the NHS (for example, commissioners and providers coordinating their involvement activities so they do not duplicate), and between the NHS and other partners – including local authorities, social care providers, Healthwatch and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector organisations that already have links to and knowledge of communities.

Terminology

In this guidance we talk about working in partnership with people and communities. We use this phrase to cover a variety of approaches such as engagement, participation, involvement, co-production and consultation. These terms often overlap, mean different things to different people, and sometimes have a technical or legal definition too.

By people we mean everyone of all ages, their representatives, relatives, and unpaid carers. This is inclusive of whether or not they use or access health and care services and support. Communities are groups of people that are interconnected, by where they live, how they identify or shared interests. They can exist at all levels, from neighbourhood to national, and be loosely or tightly defined by their members.

Community-centred approaches recognise that many of the factors that create health and wellbeing are at community level, including social connections, having a voice in local decisions, and addressing health inequalities.

We refer to health and care systems as all organisations working to improve people’s physical and mental health, nationally and locally, including the NHS, local authorities and social care providers. We use the term trusts to refer to NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts.

Integrated care systems (ICSs) are partnerships of health and care organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up services, and to improve the health of people who live and work in their area.

Each ICS consists of an:

- Integrated care board (ICB): a statutory organisation that brings the NHS together locally to improve population health and care

- Integrated care partnership (ICP): a statutory committee (established by the ICB and relevant local authorities) that is a broad alliance of organisations and representatives concerned with improving the care, health and wellbeing of the population.

- ICSs also include place-based partnerships and provider collaboratives. The King’s Fund animation explains more about the new organisations in the NHS and how they can collaborate with partners to deliver joined-up care.

Introduction

This new guidance sets the ambition and expectations for how integrated care boards (ICBs), NHS trusts and foundation trusts should work in partnership with people and communities in this new collaborative environment. It is also adopted as policy by NHS England and will be useful for local authorities and other partners to understand the statutory duties on NHS England, ICBs and trusts.

Many colleagues across these organisations already recognise the value of working with people and communities, and the experiences and knowledge that they contribute to improving health and care services. People and communities have the skills and insight to transform how health and care is designed and delivered. Working with them as equal partners helps them take more control over their health and is an essential part of securing a sustainable NHS.

This guidance aims to spread effective practice across all systems by building on the expertise and experience that exists and approaches already being applied (Health and wellbeing: a guide to community-centred approaches, Community-centred public health: taking a whole system approach). It provides practical advice and signposts to further information including training and resources. It also shares learning from areas where partnership is already making the vision a reality and makes clear the difference that working with people and communities makes.

The response to COVID-19 saw communities mobilise themselves to support family, friends and neighbours including those self-isolating and to encourage vaccine take-up; developing approaches that fitted local circumstances and needs (UKHSA: The community response to coronavirus (COVID-19), Health Creation Alliance: Learning from the community response to COVID19; how the NHS can support communities to keep people well). Communities worked alongside health and care partners to find innovative solutions to new challenges (National Voices: Unlocking the digital front door – keys to inclusive healthcare). There was agreement between communities and the organisations that provide services about the shared priorities. This led to joint working often with communities leading and systems responding to the needs and preferences voiced by people.

This learning should be transferred to help meet other challenges that health and care services face by listening to people and working with them to decide what will work best for them. The pandemic brought into sharp focus the disproportionate impact on certain population groups. A key part of how we address physical and mental health inequalities is to begin by listening to diverse communities and working with their knowledge, commitment and resources to improve access, experience and health outcomes.

Who is this guidance for?

This is statutory guidance issued by:

- NHS England for ICBs under section 14Z51 of the National Health Service Act 2006 in relation to their ‘public involvement’ duty under section 14Z45

- the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care for NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts under section 242(1G) in relation to their ‘public involvement’ duty under section 242(1B).

It replaces the 2017 statutory guidance for commissioners, the 2008 statutory guidance for trusts and the 2021 implementation guidance for ICSs.

As statutory guidance, this means that ICBs and trusts must have regard to this guidance. They must consciously consider the guidance and, where appropriate, be able to explain any substantial departure from it.

NHS England has its own ‘public involvement’ duty (section 13Q of the National Health Service Act 2006). It is NHS England’s policy to have regard to this guidance in the same way that ICBs and trusts are required to as statutory guidance.

NHS England is also required under section 14Z59 to conduct a performance assessment of ICBs that must (amongst other things) include how well the ICB has discharged its public involvement duty.

While it is statutory guidance for the ICBs and trusts, it supports the vision of integrated care where organisations work in genuine partnership. It is therefore relevant to the entire health and care system.

Accessible diagram text:

This guidance has the status of:

- Policy for NHS England, under its public involvement duty in the NHS Act 2006, as amended by the Health and Care Act 2022

- Statutory guidance for Integrated Care Boards, under its public involvement duty in the NHS Act 2006, as amended by the Health and Care Act 2022

- Statutory guidance for NHS trusts and foundation trusts, under their public involvement duty in the NHS Act 2006, as amended by the Health and Care Act 2022

- Good practice for other partners in Integrated Care Systems.

For ICS partners it will be used by:

- Integrated care partnerships (ICPs) to help inform their strategies, during the development of which they must involve people

- place-based partnerships as a guide on how they involve people in decision-making processes and engage them on plans for change

- provider collaboratives, clinical networks and cancer alliances, as it supports working with people on improving whole care pathways across multiple places and systems

- health and care partners involved in research, as the guidance supports working with communities to identify research needs (both locally and across care pathways), and to be involved in shaping research studies that align with what matters to communities

- Primary care networks for their work at neighbourhood level with local communities, to understand local needs and reduce health inequalities.

It will also be of interest to other partners within health and care systems as good practice, including local authorities – in particular health overview and scrutiny committees (HOSCs), health and wellbeing boards (HWBs) and other local democratic structures – voluntary community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector organisations, social care providers, local Healthwatch and patient groups. Finally, it is relevant to people interested in how their NHS should work with them.

This guidance complements separate guidance on involving people in their own health and care (there are legal duties on involving people in their own health and care, covered in separate guidance. An update to this guidance will be published in 2022).

Setting the ambition

The ambition is for health and care systems to build positive, trusted and enduring relationships with communities to improve services, support and outcomes for people.

This means a health and care system that:

- listens more and broadcasts less

- undertakes engagement which is ongoing and iterative, not only when proposing changes to services

- is focussed on and responds to what matters to communities and prioritises hearing from people who have been marginalised and those who experience the worst health inequalities

- works with and through existing networks, community groups and other places where people identify and feel comfortable

- develops plans and strategies that are fully informed and understood by people and communities

- learns from people and communities, using insight, data and a range of approaches to understand whether their needs are being met and what their priorities, ambitions and ideas are

- provides clear feedback about how people’s involvement leads to improvement

- invests in different approaches to working with people and communities, enabling them to contribute meaningfully in ways that are safe and accessible for them

- shares power with communities so they have a greater say in how health services are shaped and can take responsibility to improving their health.

Legal duties and responsibilities

Public involvement legal duties

The legal duties on public involvement require organisations to make arrangements to secure that people are appropriately ‘involved’ in planning, proposals and decisions regarding NHS services.

Annex B provides the detail on these legal duties, when they are likely to apply and how they can be met. Key requirements of ICBs, trusts and NHS England include that they:

- assess the need for public involvement and plan and carry out involvement activity

- clearly document at all stages how involvement activity has informed decision-making and the rationale for decisions

- have systems to assure themselves that they are meeting their legal duty to involve and report on how they meet it in their annual reports.

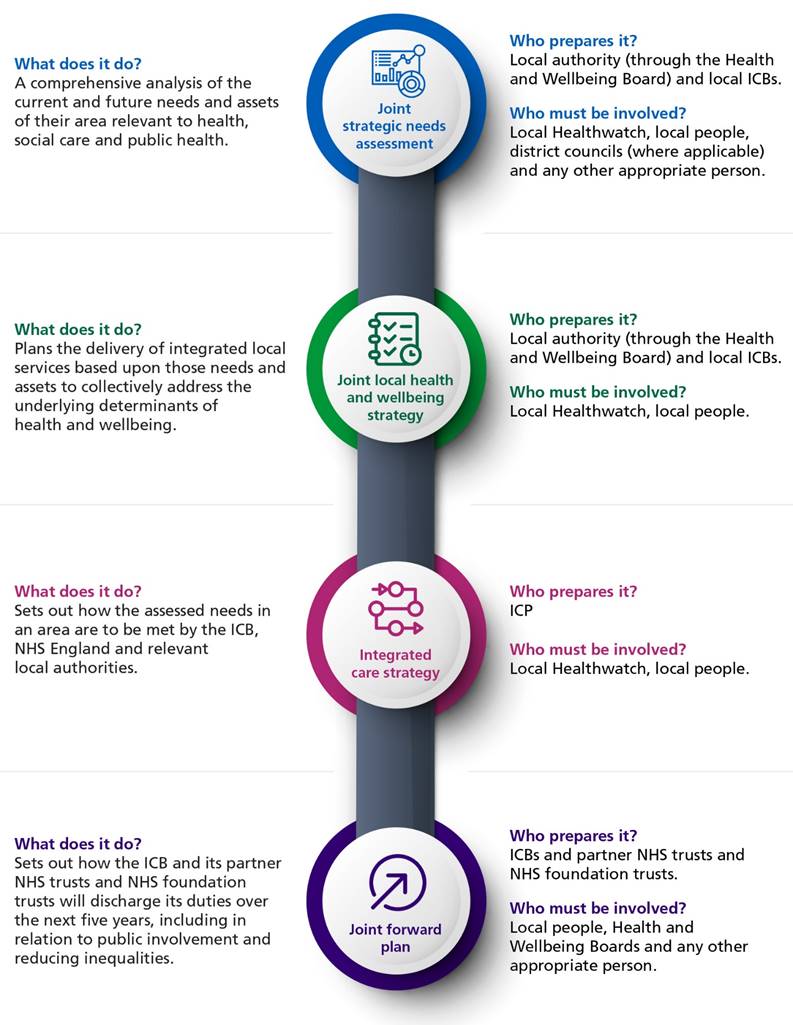

ICPs, place-based partnerships and provider collaboratives also have specific responsibilities towards participation, summarised below. There are statutory requirements for ICBs and ICPs to produce strategies and plans for health and social care, each with minimum requirements for how people and communities should be involved (see Annex B).

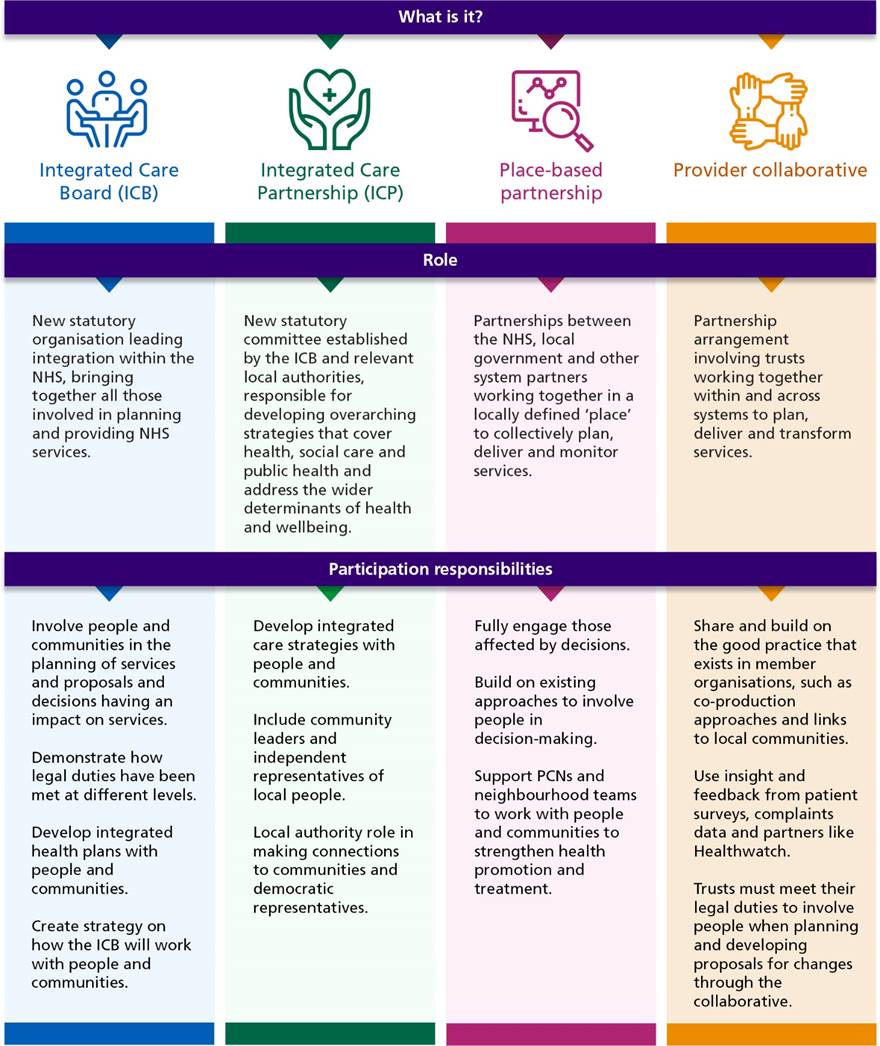

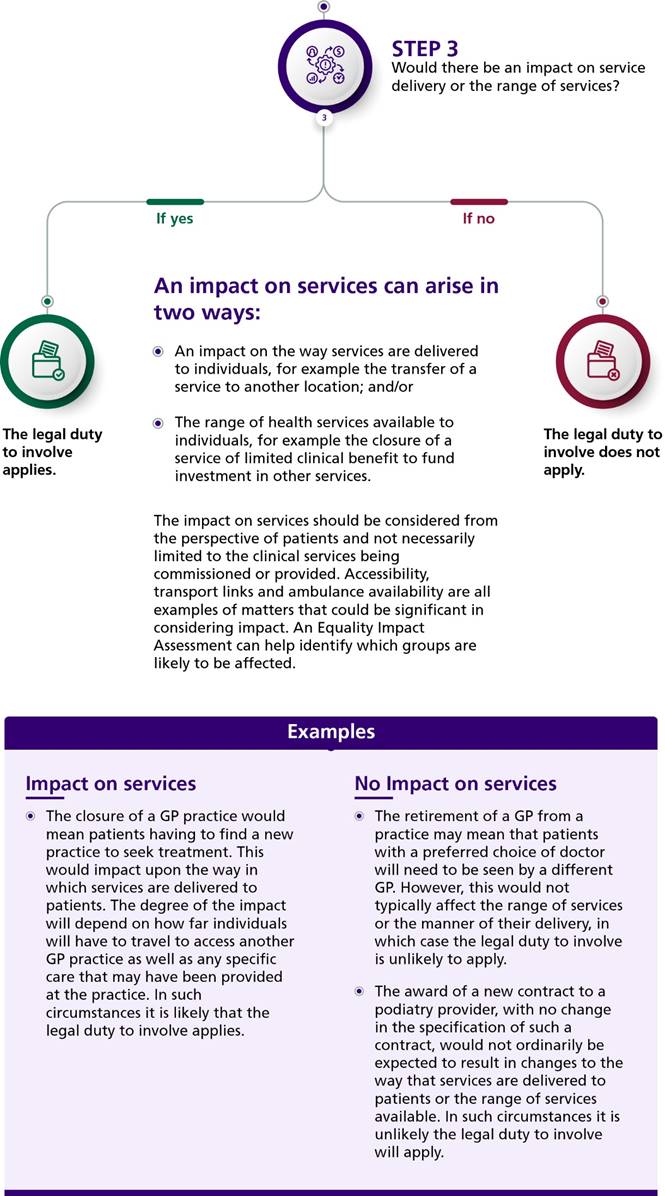

Accessible diagram text:

Different parts of the ICS have their own participation responsibilities. The roles of the new organisations and partnerships are described in this diagram along with their participation responsibilities.

Integrated care board (ICB)

Role: New statutory organisation leading integrating within the NHS, bringing together all those involved in planning and providing NHS services.

Participation responsibilities:

- Involve people and communities in the planning of services and proposal and decisions having an impact on services

- Demonstrate how legal duties have been met at different levels

- Develop integrated health plans with people and communities

- Create strategy on how the ICB will work with people and communities

Integrated care partnership (ICP)

Role: New statutory committee established by the ICB and relevant local authorities, responsible for developing overarching strategies that cover health, social care and public health and address the wider dominants of health and wellbeing.

Participation responsibilities:

- Develop integrated care strategies with people and communities

- Include community leaders and independent representatives of local people

- Local authority role in making connections to communities and democratic representatives

Place-based partnership

Role: Partnerships between the NHS< local government and other system partners working together in a locally defined ‘place’ to collectively plan, deliver and monitor services

Participation responsibilities:

- Fully engage those affected by decisions

- Build on existing approaches to involve people in decision-making

- Support PCNs and neighbourhood teams to work with people and communities to strengthen health promotion and treatment

- Provider collaborative: Partnership arrangement involving trusts working together within and across system to plan, deliver and transform services

Participation responsibilities:

- Share and build on the good practice that exists in member organisations, such as co-production approaches and links to local communities

- Use insight and feedback from patient surveys, complaints data and partners like Healthwatch

Trusts must meet their legal duties to involve people when planning and developing proposals for changes through the collaborative

The triple aim duty

NHS England, ICBs, NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts are subject to the new ‘triple aim’ duty in the Health and Care Act 2022 (sections 13NA, 14Z43, 26A and 63A respectively). This requires these bodies to have regard to ‘all likely effects’ of their decisions in relation to three areas:

- health and wellbeing for people, including its effects in relation to inequalities

- quality of health services for all individuals, including the effects of inequalities in relation to the benefits that people can obtain from those services

- the sustainable use of NHS resources.

Effective working with people and communities is essential to deliver the triple aim, as shown in the diagram below.

Other relevant legal duties

Effective working with people and communities will also inform and support organisations in meeting other legal duties:

- Equalities: The Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) of the Equality Act 2010

- Health inequalities: The National Health Services Act 2006

- Social value: Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012.

Annex B explains how working with people and communities can help meet these duties.

The triple aim duty and participation

Accessible diagram text:

Working with people and communities will help to meet the triple aim duty:

1. Better population health and wellbeing:

- Health inequalities: Improve understanding of the experiences, perspectives and needs of people and communities that experience the worst health inequities, including inclusion health groups, and working together, beyond clinical boundaries, to develop solutions

- Data and Insight: Accessing data and insight including qualitative data from communities and the VCSE sector, to build knowledge of the communities we service, and the impact of wider dominants of health

- Assets: Understanding the assets in our communities that will help to improve population health and wellbeing and to strengthen understanding of community needs and perspectives

2. Better quality of services for individuals:

- Designing services: Designing services in partnership with people so they meet their needs and preferences and reflect experience

- Approaches and solutions: Jointly develop improvement approaches and solutions to concerns about quality, including patient safety and experience

3. Improved efficiency and sustainability:

- Prioritising resources: Prioritising resources to where they have the greatest impact based on the needs, knowledge and experience of communities

- Understanding barriers: Understanding the barriers to access which impact on the efficiency and sustainability of services and work together in solutions to address them.

Why work in partnership?

Accessible diagram text:

There are several benefits of partnership with people and communities, shown in this diagram:

- Improved health outcomes

- Value for money

- Better decision-making

- Improved quality

- Accountability and transparency

- Participating for health

- Meeting legal duties

- Addressing health inequalities

The benefits of partnership

Improved health outcomes

Working in partnership with people and communities creates a better chance of creating services that meet people’s needs, improving their experience and outcomes. People have the knowledge, skills, experiences and connections services need to understand in order to support their physical and mental health. Partnership working contributes to defining ‘shared outcomes’ that meet the needs of their communities (GOV.UK: Health and social care integration: joining up care for people, places and populations. This is particularly relevant in the context of population health management and reducing health inequalities.

Value for money

Services that are designed with people and therefore effectively meet their needs are a better use of NHS resources. They improve health outcomes and reduce the need for further, additional care or treatment because a service did not meet their needs first time.

Better decision-making

We view the world through our own lens and that brings its own judgements and biases. Business cases and decision-making are improved when insight from local people is used alongside financial and clinical information to inform the case for change. Their insight can add practical weight and context to statistical data, and fill gaps through local intelligence and knowledge. Challenge from outside voices can promote innovative thinking which can lead to new solutions that would not have been considered had the decision only been made internally.

Improved quality

Partnership approaches mean that services can be designed and delivered more appropriately, because they are personalised to meet the needs and preferences of local people. Without insight from people who use, or may not use, services, it is impossible to raise the overall quality of services. It also improves safety, by ensuring people have a voice to raise problems which can be addressed early and consistently.

Accountability and transparency

The NHS Constitution states: ‘The system of responsibility and accountability for taking decisions in the NHS should be transparent and clear to the public, patients and staff.’ Organisations should be able to explain to people how decisions are made in relation to any proposal – and how their views have been taken onboard. Transparent decision-making, with people and communities involved in governance, helps make the NHS accountable to communities. Engaging meaningfully with local communities build public confidence and support as well as being able to demonstrate public support for proposals.

Participating for health

Being involved can reduce isolation, increase confidence and improve motivation towards wellbeing. Individuals’ involvement in delivering services that are relevant to them and their community can lead to involvement at a service level and to more formal volunteering roles and employment in health and care sectors. It is well recognised that doing something for others and having a meaningful role in your local community supports mental health. Getting involved can be health creating – being part of a community and being in control is good for our health.

Meeting legal duties

Although this should not be the primary motivation, failure to meet the relevant legal duties risks legal challenge, with the substantial costs and delays that entails, and damage to relationships and trust and confidence between organisations, people and communities.

Reducing health inequalities

Joint solutions

Tackling the causes and consequences of health inequalities is a central priority for health and care systems. It is one that has been given new momentum by the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on those people and communities who already face the worst inequalities (Public Health England: COVID-19: review of disparities in risks and outcomes).

Health inequalities can be reduced by jointly identifying solutions, developed in partnership with people using community-centred approaches. This builds on the approach of CORE20PLUS5 – a national framework that helps define the population groups in each system experiencing health inequalities. Hearing their experiences and understanding the barriers these groups face in accessing care and treatment is an important part of addressing unequal access to services. From there we can work with them to co-create community-centred solutions.

Focussing engagement on groups who have been marginalised and excluded helps tackle the inverse care law, whereby those with the most need for services are the least likely to receive them and least likely to feel safe to participate. By building engagement approaches that include people who are currently not well supported by existing services, systems can design models of care that meet the needs of all their communities and address inequalities. This includes recognising that some communities may require different approaches to meet their needs. Population groups facing the worst health inequalities are often the most disempowered, with the lowest levels of various markers for control, belonging and wellbeing. Working with the most marginalised groups needs to be based on building trust and connection as an important foundation for improving their health outcomes.

Collaborative approaches

The NHS cannot do this alone. Wider determinates of health – for example, poverty, discrimination, educational attainment, employment and housing – relate to barriers that the NHS by itself cannot overcome. Collaboration brings an opportunity to capture a holistic picture of inequalities and work with people and communities on joined up solutions. Local authorities and other partners are well placed to understand the social determinants of health and how they can be addressed together.

There is also an opportunity to share power and strengthen relationships with people that experience inequalities. They can be involved in agreeing ambitions, shared outcomes and plans to improve health outcomes through commissioning and service delivery. For example, they could work with the groups identified through CORE20PLUS5 to make decisions collaboratively on how to address their specific health and care needs. This helps ensure intended objectives are relevant, achievable, and based on skills, experiences and what really matters to the people they are intended to help. This means proactively seeking their participation and using approaches that enable diverse communities to contribute and take more control.

It is important to recognise that boosting the power of communities to make decisions and encouraging them to take more responsibility has a strong health creating effect. If the NHS can support people and communities to take more control, they will be helping to improve health and address inequalities (NHS England will publish guidance on addressing health inequalities in 2022/23).

Building a culture of partnership

Leadership is vital to achieving these benefits. Communities and staff will look to system leaders to role model a culture of partnership, to demonstrate that their views are taken seriously and that they prioritise giving people a genuine part in decisions about how services are designed and delivered (Kings Fund: Understanding integration: How to listen to and learn from people and communities. Leadership can be a joint endeavour, with leaders from systems and from within communities working together.

Collaborative and inclusive leadership means seeing participation as everybody’s business and fundamental to meeting shared objectives. This means leadership teams that value participation as part of all their roles and seeking assurance that it is happening within their organisation, rather than being delegated to one individual who is accountable for ensuring it happens. This sets the tone for practitioners and communities to work, learn, and improve together. It creates the culture to enable staff to innovate and collaborate in new ways and gives them permission and autonomy to try things out, to learn and to celebrate success.

This requires a commitment for sufficient funding, resources, training and support to do so effectively, and allowing time to build trust and relationships. This will support working with all groups of people and communities, including those whose voices are not currently heard in a meaningful way.

Senior leaders and decision-makers will want to make sure that they understand and take action on what matters to people in the decisions that they are responsible for and to work with partners to really make sure that people are at the centre of everything they do. Spending time with local communities, listening to and building understanding about their experiences is essential. This visible leadership helps to unlock potential and demonstrates that working in partnership with people is everyone’s business.

Ten principles for working with people and communities

The guidance is based on ten principles that will help health and care organisations develop their ways of working with people and communities, depending on local circumstances and population health needs.

They are intended to be a golden thread running throughout systems, whether activity takes place within neighbourhoods, in places, across system geographies or nationally.

They have been developed from good practice already taking place and are intended to support existing approaches which may exist locally. They will form the basis of NHS England’s assessment of how well integrated care boards meet their legal duties (see 12.1 below). However, they can be used by all organisations to develop effective ways of working in partnership.

1. Ensure people and communities have an active role in decision-making and governance

- Build the voices of people and communities into governance structures so that people are part of decision-making processes

- Recognise the collective responsibility at board level for upholding legal duties, bringing in lay perspectives but avoiding creating isolated, independent voices

- Make sure that boards and communities are assured that appropriate involvement with relevant groups has taken place (including those facing the worst health inequalities); and that this has an impact on decisions.

- Ensure that effective involvement is taking place at the appropriate level, including system, place and neighbourhood, and that there is a consistency and coordination of approaches

- Support people with the skills, knowledge and confidence to contribute effectively to decision-making and governance

- Make sure that senior leaders role model inclusive and collaborative ways of working.

Case study: Building a consistent approach to involvement across North West London integrated care system (ICS)

In December 2019, North West London ICS launched the EPIC (Engage – Participate –Involve – Collaborate) programme to try to address some of the challenges around how it works with residents. A key strand of the programme was co-production of a future, best practice approach to resident involvement in the CCG and future ICS. Despite some very good practice, the public had not previously been involved systematically in shaping the ICS’s work and many communities were not being effectively engaged. The ICS’s approach now includes:

- ‘Collaborative spaces’ -open meetings where health and care colleagues come together with people to discuss health and care issues

- Outreach with all our communities including targeted involvement of groups we have not successfully involved in the past

- Lay partners to sit on key programmes/workstreams as appropriate.

This approach is assured via North West London’s involvement charter.

2. Involve people and communities at every stage and feed back to them about how it has influenced activities and decisions

- Take time to plan and budget for participation and start involving people as early as possible so that it informs options for change and subsequent decision-making

- Involve people and communities on a continual basis, as part of meaningful partnerships, rather than taking a stop-start approach when decisions are required. As a result, there will be much greater, ongoing awareness of the issues, barriers, assets and opportunities

- Be clear about the opportunity to influence decisions; what taking part can achieve; and what is out of scope

- Record and celebrate people’s contributions and give feedback on the results of involvement, including changes, decisions made and what has not changed and why

- Keep people informed of changes that take place sometime after their involvement and maintain two-way dialogue so people are kept updated and can continue to contribute

- Take time to understand what works and what could be improved.

3. Understand your community’s needs, experiences, ideas and aspirations for health and care, using engagement to find out if change is working

- Use data about the experiences and aspirations of people who use (and do not use) health and care services, care and support; and have clear approaches to using this information and insight to inform decision-making and quality governance

- Work with what is already known by partner organisations, from national and local data sources, and from previous engagement activities including those related to the wider determinants of health

- Share data with communities and seek their insight about what lies behind the trends and findings. Their narrative can help inform about the solutions to the problems that the data identifies

- Understand what other engagement might be taking place on a related topic and take partnership approaches where possible, benefiting from your combined assets. This will also help avoid ‘consultation fatigue’ amongst communities, by working together in an ongoing dialogue that is not limited by organisation boundaries

- Build on existing networks, forums and community activities to reach out to people rather than expecting them to come to you. Be curious and eager to listen; don’t assume you know what people will say or what matters to them

- Involve people in designing evaluation frameworks and deciding what ‘good’ looks like, using measures of change that matter to them. Include evidence collection in engagement plans to demonstrate the impact that working with people and communities has had.

Case study: Community conversations on public mental health

Poor mental health is a major challenge facing London, and the prevalence of mental health problems is often much higher in the communities facing the deepest inequalities.

Recognising this, in 2017/18 the Mental Health Foundation and Thrive LDN co-ordinated 17 community conversations across half of the city’s boroughs, involving more than 1000 Londoners, with the aim of finding out how local systems could best implement a public mental health approach.

These conversations went far beyond the consultations that communities had previously seen on mental health services: as well as getting ideas for providing ‘services when and where needed’ they were designed to find ways of improving the determinants of mental health to enable prevention for everyone, early intervention for those at risk, and effective support for those who need it.

Evaluation of these conversations by the Mental Health Foundation found several ways that they tangibly influenced public mental health initiatives in the areas where they were held. For example:

- in Hackney, they brought together public health and planning teams around the design of a new leisure centre to ensure high quality community space

- in Enfield, the community conversation influenced the plans for a major regeneration, prompting greater focus on creating ‘mentally healthier’ places with better access to green and community space.

The community conversations also led to the development of a network of mental health champions across London and new job roles, including a specialist public mental health position and a voluntary sector liaison post.

More information on the process and results are in the Londoners Said and Londoners Did reports from the Mental Health Foundation.

4. Build relationships based on trust, especially with marginalised groups and those affected by inequalities

- Proactively seek participation from people who experience health inequalities and poorer health outcomes, connecting with trusted community leaders, organisations and networks to support this

- Consider how to include people who do not use services, whether because they do not meet their needs or are inaccessible, and reach out to build trust and conversations about what really matters to them

- Work with people and communities from the outset, taking time to build trust, listen and understand what their priorities are

- Be honest and realistic about what is in scope and where they can set the agenda for change

- Tailor your approach to engagement to include people in accessible and inclusive ways so you include those who have not taken part before. This includes recognising that some communities will not feel comfortable discussing their issues and needs within wider meetings, so may need bespoke approaches. They may need additional support to take part including reimbursements for their time

- When reporting on engagement activity, explain the needs and solutions for different communities rather than simply aggregating all data and feedback together. This also supports equality impact assessments.

Case study: Embedding Cultural Awareness in Maternity and Neonatal Care

For over 10 years, the East of England Local Government Association via the Strategic Migration Partnership has been delivering a wide range of engagement and integration projects with ethnic minority groups in the East of England.

They understand the challenges health and care staff can experience when supporting a wide range of culturally diverse and dynamic groups. This can include language barriers, a reluctance to engage with professionals and a mistrust of the NHS system because of past relationships with authorities in countries of origin. They also understand that for many ethnic minority groups, healthcare in the UK can be seen as confusing and often inaccessible due to a lack of appropriate information and a reliance on people having access to digital devices.

In response to the challenges faced by the healthcare professionals and ethnic minority groups, they have worked to create cultural awareness workshops, which are both effective and efficient at ensuring the development of sustainable maternity and neonatal care pathways for different groups across the region.

The workshops were an opportunity to identify engagement issues specific to the East of England and delivered by members and advocates of ethnic minority groups considered hard to engage with across the region, including LGBTQ+ groups, African groups, Orthodox Jewish groups, Gypsy and Traveller groups, Roma groups, South Asian groups, Eastern European groups, Asylum Seekers and Refugees.

5. Work with Healthwatch and the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector as key partners

- Build strong partnerships with Healthwatch and the Voluntary Community and Social Enterprise sector to bring their knowledge and reach into local communities. Work with them to facilitate involvement from different groups and develop engagement activities

- Understand the various types of Voluntary Community and Social Enterprise sector organisations in your area, from larger national charities to local user-led groups, their links to different communities and how the NHS can connect with them

- Recognise that resources can be limited and that organisations may need financial support and capacity building to take on partnership roles

- When commissioning other organisations to work with communities, ensure that decision-makers remain personally involved and hear directly what people or their representatives have to say.

6. Provide clear and accessible public information

- Develop information about plans that is easy to understand, reflecting the communication needs of local communities and testing information where possible

- Where accessible formats such as easy read and translations into other languages are used, these should be ready at the same time as other materials

- Providers of NHS care must meet their requirements under the Accessible Information Standard for the information and communication needs of people in their own care. The same principles can be applied for public information so that it is clear and easy to understand, for example, taking steps to ensure that people receive information which they can access and understand, and receive communication support if they need it

- Be open and transparent in the way you work, being clear about where decisions are made and the evidence base that informs them. Provide people with an honest picture of the health and care landscape, along with resource limitations and other relevant constraints. Where information must be kept confidential, explain why

- Make sure you describe how communities’ priorities can influence decision-making, including how people have influenced research priorities or planning for future health care ambitions; and how people’s views are considered. Also ensure that you regularly feedback to those who shared their views and others about the impact this has made

- Provide feedback in inclusive and accessible ways, that suit how people want or are able to receive it

- Make sure information on opportunities to get involved is clear and accessible and encourage a wide range of people to take part; including targeting information at particular communities who might traditionally not be involved.

7. Use community-centred approaches that empower people and communities, making connections to what works already

- Support and build on existing community assets, such as activities and venues which already bring people together such as faith communities, schools, community centres, local businesses and community-centred services, including those that involve link workers, community champions and peer support volunteers.

- Adopting asset based approaches to community development to understand how these assets can support people’s physical and mental health. Link with local authorities where they already have approaches in place and consider jointly funding.

- Build trust and meaningful relationships in a way that people feel comfortable sharing ideas about opportunities, solutions and barriers. Design, deliver and evaluate solutions together that are built around existing community infrastructure.

- Recognise existing volunteering and social action that supports physical and mental health and create the sustainable conditions for them to grow (for example, by providing places to meet, small grants or community development support).

Case study: working at neighbourhood level in Morecambe Bay to reduce health inequalities

This project was designed to explore what access issues and inequalities were being experienced by a range of health inclusion and other key groups. It started with the primary care networks (PCNs) using population health management approach to identify groups of patients that may experience health inequalities. There was then an asset mapping process with each PCN group supported to identify local people and organisations that could potentially support with the work. Next, engagement took place with groups of patients and local people including young people, adults with learning disabilities and their carers and workers from migrant communities. A workshop supported people to plan how they would share what they had found and what they planned to do next with the communities they had focused on.

The PCNs have changed their services based on what they found through this work. For example, for people with learning disabilities, annual learning disability health checks are being reassessed to improve uptake and providing care in a way that makes patients feel comfortable, cared for and listened to.

Overall, participants report feeling more confident around how to engage with their local communities, and how the process can be applied to other groups experiencing health inequalities to inform other improvement initiatives.

It was undertaken by Morecambe Bay CCG, North Cumbria ICS, Morecambe Bay PCNs, Co-create and other local partners.

8. Have a range of ways for people and communities to take part in health and care services

- Choose the ways of working with people and communities depending on the specific circumstances, ensuring they are relevant, fair and proportionate. Use a combination of approaches where appropriate. The approach that gives the greatest opportunity for people to take part in decision-making should be used that is suitable for the situation.

- Design activities to take place at times and in ways that encourages participation and consider the support people may need to take part, including reimbursements for their time and expenses

- Recognise that people are busy and have other priorities such as work and caring responsibilities. Ensure that there are different ways to get involved with varying levels of commitment

- Include approaches such as co-production where professionals share power and have an equal partnership with people to plan, design and evaluate together

- Using different approaches can bring in a wider range of voices beyond those who already contribute and ensure findings are more representative of the whole population

- Have clear, achievable and actionable goals that can comprise both quick wins to inspire people, as well as longer term goals that may be more challenging to achieve but may ultimately be more transformative

- Where decisions are genuinely co-produced, then people with lived experience work as equal partners alongside health and care professionals (those with learnt experience), jointly agreeing issues and developing solutions.

Case study: Co-producing a new model of community mental health support

In Somerset, the NHS, local authority and Voluntary Community and Social Enterprise sector partners have worked with people with lived experience of mental illness to co-produce community mental health services. The involvement of experts by experience as equal partners has been embedded across the programme from the beginning, and the lived experience perspective they represent has influenced key decisions about the service. They co-designed the Open Mental Health model, whereby 24/7 support is available to adults in Somerset who are experiencing mental health issues. Provision is offered through an alliance of provider organisations from the Voluntary Community and Social Enterprise sector, NHS and social care working in partnership. Experts by experience have an ongoing role as partners in the governance, continuous development and evaluation of the service.

There is more about Open Mental Health on the Rethink Mental Illness website.

9. Tackle system priorities and service reconfiguration in partnership with people and communities

- People who use health and care services have knowledge and experience that can be used to help make services better. They can put forward cost-effective and sustainable ideas that clinicians and managers have not thought of, which inform planning for future healthcare development

- Communities often have longer memories than the professionals who may change roles and move. Understanding the local history of change that communities have experienced helps to learn and build trust with people

- When people better understand the need for change, and have been involved in developing the options, they are more likely to advocate the positive outcomes and involve others in the process.

10. Learn from what works and build on the assets of all health and care partners – networks, relationships and activity in local places

- Collaborate with partners across your system to build on their skills, knowledge, connections and networks

- Reduce duplication by understanding what is already known and what has already been asked, before designing the approach to engagement.

- Learn from approaches taken elsewhere in the country and how they can be adapted and applied locally

- Plan together across systems so that partnership work with people and communities is co-ordinated, making the most of partners’ skills and networks.

Annex A: Implementation

A1 – Different ways of working with people and communities

This chapter sets out a variety of approaches to working with people and communities however there is no ‘one size fits all’. The options for doing so will vary depending on the context and objectives, and there needs to be flexibility depending on the aims and scale of the programme.

A blended approach can also work well, with different approaches and ways of working used at different stages of a project to build a more detailed picture of what matters to people and what improvements can be made.

Some of the main ways to work with people are set out below. They each offer different levels of involvement, from sharing information through to more extensive ways of working such as co-design and co-production, where there is a greater opportunity for people to have influence. As a general principle, partnership should be achieved by using the most effective approach (or combination of approaches) as is feasible and suitable in any given situation.

Starting with people means going to the neighbourhoods and places where they already are and begin by listening to them about their priorities. From this we can design approaches that should ensure relevant communities can take part, recognising that different approaches work better for different groups.

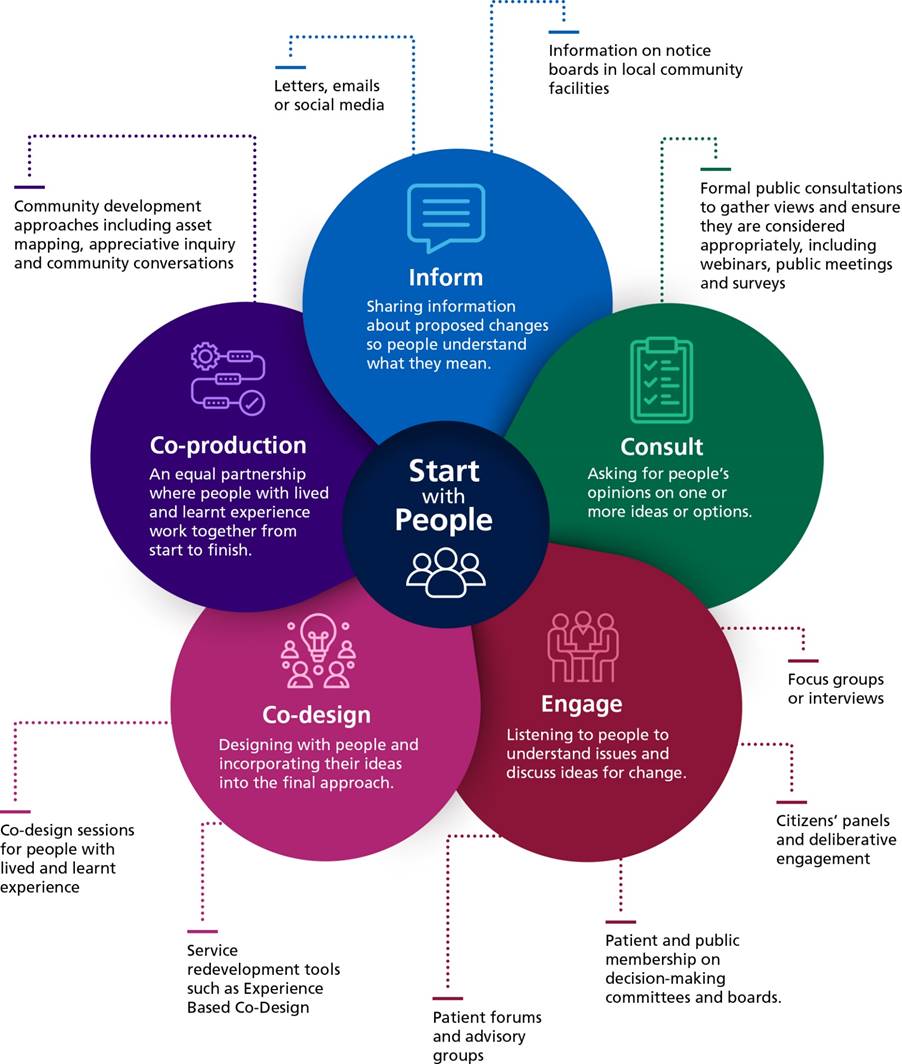

Different ways of working with people and communities

Accessible diagram text:

This diagram shows some of the different ways of working with people and communities, with examples for each

- Inform: Sharing information about proposed changes so people understand what they mean. Examples are Letters, emails or social media, and information on notice boards in local community facilities

- Consult: Asking for people’s opinions on one or more ideas or options. An example is a formal public consultation to gather views and ensure they are considered appropriately, including webinars, public meetings and surveys

- Engage: Listening to people to understand issues and discuss ideas for change. Examples are focus groups or interview, citizens’ panels and deliberative engagement, patient and public membership on decision-making committees and boards, and patient forums and advisory groups

- Co-design: Designing with people and incorporating their ideas into the final approach. Examples are service redevelopment tools such as Experience Based Co-Design and co-design sessions for people with lived and learnt experience

- Co-production: An equal partnership where people with lived and learnt experience work together from start to finish. An example is community development approaches including asset mapping, appreciative inquiry and community conversations.

For all the approaches used, there are three main pitfalls to avoid:

- Tick box exercises. Involvement is not an obstacle to overcome on the way to achieving a predetermined outcome. Any perception that it is tokenistic or that a strategy or service change has not been informed by insight from the public, will not only undermine trust, it is unlikely to be supported at local, regional or national level.

- Unrealistic timescales. Service design and service changes should be planned to achievable timescales that allow for early, ongoing and effective public involvement, including careful consideration and discussion of the views expressed by people and communities.

- Limiting public dialogue to service change proposals. While consultations necessarily focus on the proposals being consulted on, involvement should not only take place when a system wants to make changes – it should be part of how every system operates, with insights from community conversations informing and driving policy decisions. Systems should be in regular dialogue with people and communities; enabling them to also influence the agenda.

Case study: Northern Cancer Alliance’s work with communities in the recovery of urgent cancer referrals

The COVID-19 pandemic had a dramatic effect on the rate of cancer referrals across England. At the start of the pandemic the Northern Cancer Alliance saw referral rates across the region drop to 40.9% of pre-pandemic levels (April 2020). The Alliance decided to build on the national ‘Help Us to Help You’ campaign with locally produced material. This local campaign focussed on health inequalities by focussing on specific tumour groups and communities where recovery levels were slowest.

Key to all aspects of the Northern Cancer Alliance work plan is the effective involvement of the public. The Alliance value to ‘always involve the right people at the right time’ was a fundamental aspect of the design and delivery of the campaign. With a focus on health inequalities, the Cancer Alliance brought together the Alliance Lay Representatives, people with lived experience, the Be Cancer Aware team and community groups to co-produce the campaign.

The campaign produced short films made by people with lived experience of cancer, people with a learning disability and people from minority ethnic groups in different languages. There was also patient information and campaign webpages produced by the Northern Cancer Alliance Lay Representatives.

To reach as many people as possible, the campaign worked with community assets, for example, by distributing leaflets, posters and magazines via food banks and other venues in the most deprived areas across the region. This element of the campaign was supported by local community organisations who already had links to wider groups of people and the Alliance Cancer Community Awareness Workers. As a result, the campaign contributed to a recovery of urgent cancer referrals.

Existing sources of feedback and insight

The starting point for any involvement is to consider existing sources of insight about the needs and experiences of different groups of people – what do you already know, what have people already told you? A review of existing information can save time and money and point to gaps in insight, while also avoiding asking people to repeat themselves. This helps to ensure that involvement is focused, meaningful and avoids duplication. This may be information held by partner organisations, including patient feedback, complaints, needs assessments and insights collected during previous activities. Consider whether the context of this previous work has changed significantly and when it took place to understand whether it is still relevant.

Involving partners in the planning process helps identify what is already known and also where the gaps are. Some people, such as those in inclusion health groups (see next chapter) and others who face social exclusion, may be systematically missed in feedback, qualitative and quantitative data sources. For example, if existing ways to give feedback are not accessible for people with learning disabilities, then their views are more likely to be missing.

One source of insight into population health needs are the intelligence functions that ICSs are building. These are system-wide, multi-disciplinary collaborations which share data and provide analytical support to help understand their local contexts. A key purpose of the intelligence function will be to support a population health management approach to care, including by pooling information and data held by partners on a local population’s health and care needs, such as granular intelligence on inequalities across different population groups (see NHS England resources for more on population health management). Intelligence functions should work with patient experience and engagement colleagues to ensure that qualitative and quantitative insights about the population are informing the interpretation of other analyses and are given equal weight in decision-making. Contextualising this intelligence with people and communities is essential and needs to be undertaken in sensitive and accessible ways.

ICBs and trusts can work in partnership with local authorities (in particular local health scrutiny functions and public health, social care and housing teams), other ICS partners and local communities to share insight and develop a detailed understanding of population health needs. A combination of national data tools, insight collected by partners and local engagement can be used to understand what works for different communities. Combined with insights drawn from the community, data can support primary care and neighbourhood teams to increase uptake of preventative services while also tackling health inequalities by identifying those groups that may currently be underserved (Next steps for integrating primary care: Fuller Stocktake report, NHS England, May 2022). One approach some ICSs are taking is to set up a network of engagement colleagues across partner organisations to share insight and coordinate engagement (see case study below).

Examples of insight and feedback sources:

- ·National patient surveys

- Friends and Family Test

- Local surveys and engagement by the NHS and local authorities

- Social media and review websites

- Local Healthwatch reports and Healthwatch England national reports

- Intelligence from the VCSE sector and local authorities

- Care Quality Commission (CQC) reviews, surveys and reports

- Patient Participation Groups (PPGs)

- Complaints and compliments

- Patient Experience Library

- Patient Safety Specialists

- Patient experience discussions at System Quality Groups

- Staff feedback including their own views

- Mapping of previous consultation and engagement activities including those by partner organisations

- Local Health Profiles

- ICS intelligence functions

- Local authority reports including Director of Public Health annual report, joint strategic needs assessment and joint health and wellbeing strategy and reviews by scrutiny committees.

Case study: System insight group and patient and public insight library at Derby and Derbyshire integrated care system

During the early stages of COVID-19, partner organisations within the Derby and Derbyshire ICS wanted to gather insights on how people were experiencing the pandemic and how it affected their lives. Residents in Derby and Derbyshire began to get inundated with separate requests to share their experiences and fill in surveys.

To avoid duplication, these efforts needed to be co-ordinated, so the ICS set up a System Insight Group, bringing together patient and public experience and engagement leads from NHS trusts, the local authorities and the VCSE sector. Its vision is to develop a culture of making insight-led decisions across the ICS. Insight could be from evidence, research, reflections, conversations, observations, and from any number of different sources. The aim of the System Insight Group was to link the types of insight together.

The System Insight Group has developed a Patient and Public Insight Library set up on the NHS Future platform. New insight is being added to the library on a regular basis, and any member of staff can join. The aim is to assist decision-makers to find current insight in the system, with the aim of avoiding duplication and consultation fatigue.

The group has also produced a report on Remote Access to Health and Care during the pandemic. The report pulled together a large proportion of insight and summarised the key themes. The report is being used by ICS partners when making decisions about the recovery of services, meaning that additional engagement will only be needed if it fills a gap in insight within the report. A digital inclusion checklist was developed using the report and will be promoted to all service providers to ensure good practice in remote access implementation programmes.

Patient participation groups

It is a contractual requirement for every GP practice to have a Patient Participation Group (PPG). The form a PPG takes is not specified and this provides flexibility for practices to work in partnership with people and communities in ways that best support the practice populations. While the PPG is one of the main ways General Practice have used to engage with patients, it should not be the only approach if it does not reach diverse groups, people with the worst health inequalities or people not accessing the services. These groups are more likely to be hesitant about getting involved in traditional PPG models. However, PPGs do not need to be limited to the meeting style group which has become the most common. Primary care networks (PCNs) and practices need to consider if the form of the present PPG supports people to take part or if other approaches are also needed to widen participation. This animation has some useful principles to use as a starting point to think through how practices currently hear the voice of their community and where the gaps are. While the main focus of a PPG is on making improvements to its local practice, their insight and experiences can be relevant to its PCN. PCNs can also learn from their practices’ PPGs about how different structures can effectively engage diverse groups.

Co-production

Co-production is a way to involve people by sharing power with them. The Coalition for Personalised Care defines co-production as:

‘a way of working that involves people who use health and care services, carers and communities in equal partnership; and which engages groups of people at the earliest stages of service design, development and evaluation.’

Co-production can be used strategically, to design services, make quality improvements, design and undertake research and innovation, and develop participatory budgets. At an individual level, it is the cornerstone of person-centred care such as personal health budgets. As well as being well suited to designing services in places and neighbourhoods, it can also be applied strategically for systems and national organisations.

The starting principle is that people with ‘lived experience’ are often best placed to advise on what support and services will make a positive difference to their lives. When done well, co-production helps to ground discussions and to maintain a person-centred perspective.

Where partnerships are genuinely equal, professionals are comfortable with not having the answers and with sharing resources, responsibility and power. This can be difficult to achieve without cultural change and support for staff and people to share power and take on co-production roles.

The Coalition for Personalised Care sets out the values and practical steps to make this ambition a reality. These includes:

- senior leaders supporting co-production through culture and behaviour

- identifying areas of work where co-production can have a genuine impact and involving people at the earliest stages

- investing in training and development so that people with lived experience and people working in the system know what co-production is and how to work in ways that enable this.

Case study: Building people’s skills and knowledge to take part in co-production

The Peer Leadership Development Programme was launched in 2014 by NHS England with the purpose of enabling people with lived experience to develop their knowledge, skills and confidence to co-produce. Over 200 peer leaders have now been trained.

The programme provides people with an opportunity to learn about how the health and care system works, about local and national policy and about how to share good information. It also teaches about change management theory and communication styles and preferences, and how people can use their personal story to create a narrative for change. This programme enables people with lived experience to access up-to-date information and support, in the same way that people working in the health and care system do. This ultimately enables people with lived experience to co-produce on a level playing field.

Case study: The difference made to the NHS England Musculoskeletal Services (MSK) programme by the Musculoskeletal Lived Experience Group (MSK LEG)

The first COVID-19 pandemic lockdown had a devastating effect on the provision of Musculoskeletal Services (MSK) services. Face-to-face consultations became a rarity, replaced by telephone and video consultations. MSK clinicians had to quickly learn new skills to assess and treat patients in these unfamiliar formats. The number of patients treated by MSK clinicians was significantly reduced as therapists were re-deployed to care for COVID patients.

It was quickly clear that going forward MSK services would need to be remodelled, not only to cope with pandemic times, but also to move into the future. The pandemic created challenges but also opportunities for new and better MSK services.

For such large-scale re-modelling to be successful it was evident that all partners would need to play a part in the development process including, perhaps most importantly, people using the services and their carers. Without their involvement it could easily result in services that people didn’t want or were not sufficiently accessible to them.

In June 2020, a MSK Recovery Group was established with lived experience partners alongside healthcare professionals. The intention was to work together collaboratively to assist with restoring and improving MSK services in the wake of the pandemic lockdowns. It evolved into MSK Lived Experience Group (MSK LEG). Each member of the new MSK LEG has experience of a relevant MSK condition and were rigorously interviewed and appointed after an open and accessible selection process.