Introduction

This guidance support all providers of acute care to enable front line staff to fulfil their legal requirements around the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) 2005; specifically when supporting people with a learning disability.

A Health Services Safety Investigations Body report in 2023 on the care of acute hospital inpatients with a learning disability in England, found variation in staff understanding and application of the MCA in the care of people with a learning disability.

Acute care leaders are asked to ensure they understand the guidance, take the actions indicated and make these resources available to all frontline staff.

To make this guidance as useful as possible for acute care providers, we provide practical tools and resources that can be downloaded:

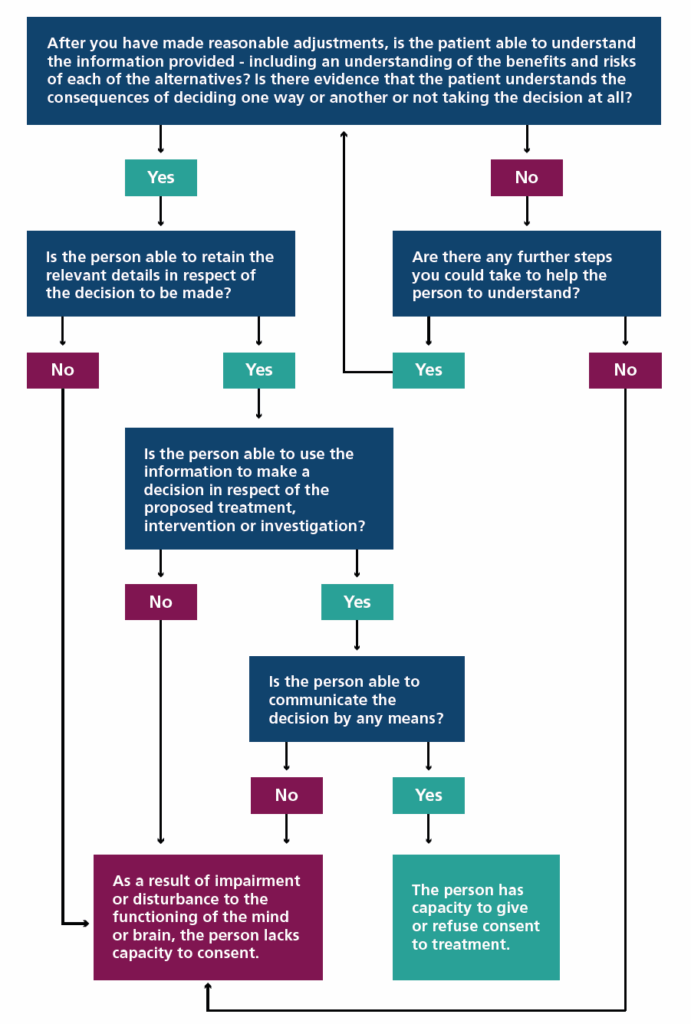

- a flowchart to help you decide how to assess capacity

- a checklist for preparing to assess the mental capacity of someone with a learning disability

- advice on how to undertake the 2-stage test for mental capacity

- reasonable adjustments that can support assessment of capacity of people with a learning disability

- template forms for recording mental capacity assessment and best interests decision including balance tables

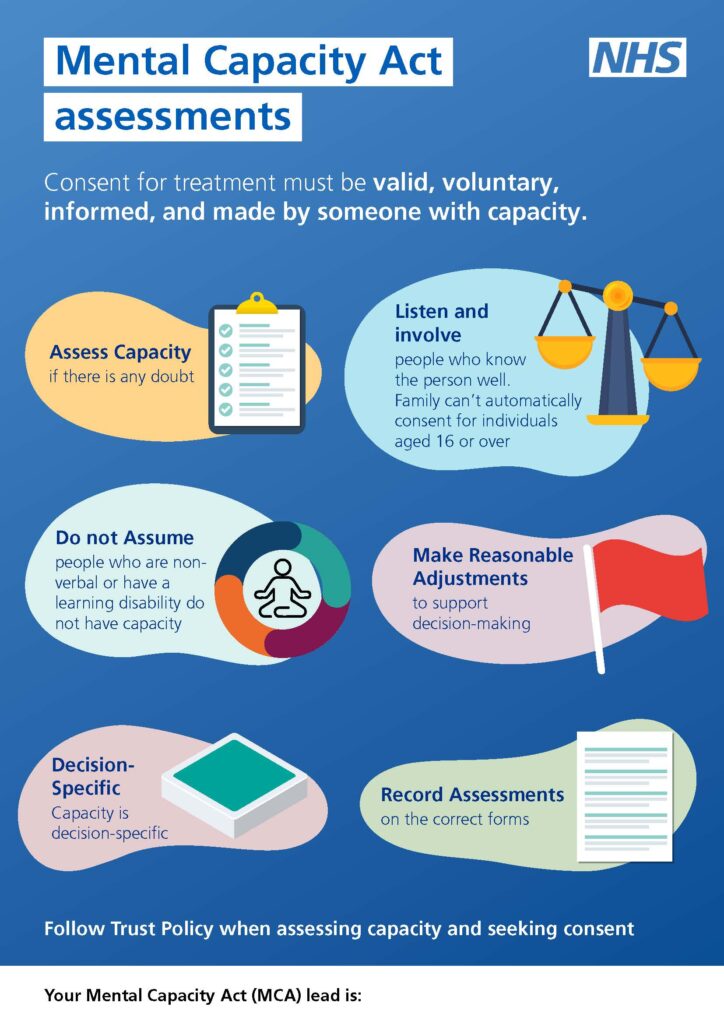

- a poster about Mental Capacity Act assessments

This guidance supports and complements NICE guidance on decision-making and capacity assessment.

Barriers to effective implementation of the MCA in acute care:

- busy clinical environments: pressure to make quick decisions may lead to shortcuts in capacity assessments

- insufficient training: lack of continuous, role-specific training on the MCA, including on issues like diagnostic overshadowing, can lead to perception of complexity of the MCA and deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS)

- misconceptions: incorrect assumption that certain conditions imply lack of capacity

- balancing autonomy and protection: ethical dilemmas in balancing patient autonomy with need for protection

- fear of litigation: overly cautious decisions due to fear of legal repercussions

- communication barriers: language, cultural differences or cognitive impairment, needing reasonable adjustments

- exclusion of family members: family members or carers insufficiently involved in decision-making

- disagreements: differing views between healthcare providers, patients and families

- inadequate record keeping: inconsistencies in documenting capacity assessments and best interests decisions; documenting capacity perceived as time-consuming, needing simplified forms

- lack of specialist support: limited access to timely specialist advice and support for complex cases

- inadequate policies and guidelines: lack of strong policies and clear guidelines

- lack of leadership commitment: leadership not prioritising MCA, affecting culture of compliance

Legal context

The MCA provides the legal framework within which decisions can be made on behalf of a person aged 16 or over in England or Wales who lacks the capacity to make those decisions for themselves.

Its ethos is to empower and protect individuals who may lack the mental capacity to make certain decisions by applying the following 5 core principles:

5 core principles of the MCA 2005

- Presumption of capacity: every individual aged 16 and over has the right to make their own decisions and must be treated as having decision-making capacity unless it is proven otherwise.

- Individuals are supported to make their own decisions: all possible practical steps are taken to support and empower individuals to make their own decisions before concluding that they lack decision-making capacity in any area. These steps may include providing reasonable adjustments to help the individual understand what they are being asked to decide or communicate their decision.

- Right to make unwise decisions: individuals have the right to make decisions that others might consider unwise or eccentric and a person should not be treated as lacking capacity just because they make an unwise decision.

- Best interests: any decision made or action taken on behalf of someone who lacks capacity must be in their best interests. A family member cannot make a decision on their own on behalf of a person over the age of 18.

- Least restrictive option: any decision about care taken on behalf of someone lacking capacity is least restrictive of their rights and freedoms.

Capacity is both time and decision specific.

Regulation 11 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 requires that care and treatment of people using services must only be provided with the consent of the relevant person. When a person is asked for their consent, information about the proposed care and treatment must be provided in a way that the person can understand.

It is also a legal duty under section 20 of the Equality Act 2010 to make reasonable adjustments to enable a disabled person who requires them to access healthcare. This includes making reasonable adjustments to help a person when their capacity is assessed.

If care or treatment is provided to someone without valid consent, both the staff member and the NHS trust are at risk of legal action. This could include accusations of assault, violating the person’s human rights (specifically their right to respect for a private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights) or being sued for battery (similar to assault). Staff could face criminal charges and the trust could face a civil claim demanding compensation (damages).

All organisations registered with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) are required to fulfil their responsibilities around the MCA, including monitoring practice within the organisation to ensure people’s rights and associated legal requirements are being recognised and met. The CQC can prosecute an organisation for a breach of Regulation 11 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 and may also take other regulatory action. It also monitors deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS).

Further information about the CQC and Mental Capacity Act can be found on the CQC website.

When to assess capacity and approach

Capacity should be assessed whenever there is a reason to doubt an individual’s ability to make a specific decision at a specific time.

While it is important to have regard to the Code of Practice that accompanies the MCA, subsequent case law (by the Supreme Court in A Local Authority v JB [2021] UKSC 52) now contradicts the approach it sets out for assessing capacity.

The approach that should be followed is a 2-stage test (see Appendix 1 for the detail; also available as a downloadable version):

1. functional test: start by identifying whether the person can make a specific decision at the specific time (reasonable adjustments may be needed to make this decision)

and only if they cannot:

2. diagnostic test: determine whether this is because of an impairment of the mind (such as psychosis) or brain (such as dementia) or some disturbance affecting the way their mind or brain works (such as drugs or alcohol) that is preventing the person from being able to make the specific decision when they need to

For stage 1 – functional test, you need to establish whether the person can:

- understand the information relevant to the decision [Essex Chambers (May 2024) Mental capacity guidance note: relevant information for different categories of decision]

- retain that information for long enough to make the decision

- weigh up the relevant arguments on each side. Can they see the various sides of the argument and how they relate one to another?

- communicate their decision (this can be by talking, using sign language or any other means)

Appendix 2 provides a checklist for preparing to assess mental capacity in practice (also available as a downloadable version).

How to support someone with a learning disability during an MCA assessment

1. Create a comfortable environment:

- choose a quiet space by ensuring the environment is free from distractions and noise

2. Use clear and simple language:

- avoid jargon and use straightforward language and avoid complex terms

- repeat and rephrase questions to ensure understanding

3. Provide information and support:

- clearly identify ahead of the assessment what the ‘relevant information’ is and the key points that the person needs to be able to understand

- explain the process by clearly explaining what the assessment involves and why it is being done

- check understanding by regularly checking if the person understands what is being discussed

4. Use aids and tools:

- visual aids: use pictures or diagrams to explain concepts

- memory aids: provide notes or reminders to help the person retain information

5. Involve trusted individuals:

- involve people who the individual trusts to provide emotional support and help with communication such as family and friends

- consider involving an advocate if they are familiar with the person and can help them feel comfortable and improve engagement

- family, friends and advocates cannot answer for the person but they can help you communicate with the person

6. Respect their pace:

- be patient: don’t rush the person, give them time to think and respond

- take breaks: offer breaks if the person seems tired or overwhelmed

- be flexible: adapt the pace and structure of the assessment to suit the individual’s needs

7. Empathise and reassure:

- show empathy by acknowledging the person’s feelings and reassuring them that their views are important

- be supportive and encourage the person and provide positive reinforcement throughout the process

Making reasonable adjustments for assessment

Decisions about a person’s capacity are not based on their condition. Every effort must be made to support a person to be able to decide themselves whether to consent or not to treatment and care. This may mean making reasonable adjustments in assessing capacity for people with a learning disability; these can be crucial.

Reasonable adjustments will differ for each person, irrespective of their presentation or diagnosis. They should be personalised to the person’s needs.

Reasonable adjustments that can support assessment of capacity of people with a learning disability

(not an exhaustive list; also available as a downloadable version)

1. Environment: consider where is the best place for the person to have their mental capacity assessed. Could it be done at home? If in hospital, which is the quietest or best room or area?

2. Timing: consider the best time of day for the person to have their mental capacity assessed. A person’s medication or health condition may mean they are less alert early in the morning.

3. Reduce a person’s pre-appointment anxiety by sending them information about what to expect when they arrive, and in the right format for them. This should include directions, using visual aids such as pictures if needed, and information about the location and the team they will meet.

4. Support people to prepare for the mental capacity assessment – for example, remind them they can bring things like fidget spinners, communication aids, comforting objects and ear defenders for use before and after their appointment.

5. Provide accessible information, for example, Easy Read, plain English, videos, posters, leaflets to support the conversation, ensuring the needs of people with different communication preferences and abilities are met.

6. Sometimes it can be helpful to give the person information over a period of time.

7. Allow extra time for the assessment so that you are not rushed and can give the person the time they need to respond.

8. Allow family members or carers to stay with the person and be involved in the assessment. They may help you best communicate with the person and interpret what they say, as well as helping the person to remain calm or to speak up if they are not feeling confident.

9. Take particular care to speak clearly and plainly, avoiding medical jargon when giving information and asking questions. Use communication supports where appropriate (for example, symbols, pictures, Makaton signs, technology). Check that the person has understood what you have told or asked them.

10. When explaining procedures or interventions, spend time demonstrating the equipment or take the person round the ward or theatre so they can get used to the environment. Give the person enough time to think about the information so they can make an informed choice. Some people may also need extra time to make a decision through with the people they trust and who help them to make other decisions about their life, for example a parent or a friend.

Look to see if the individual has a reasonable adjustment digital flag on their electronic patient record. This will indicate the reasonable adjustments they require.

Do not assume that someone without a flag does not have any reasonable adjustment needs. Ask the person or their carers what reasonable adjustments might help them make the decision for themselves. If you identify someone as requiring reasonable adjustments who does not already have a flag, add one to their record (see the NHS England reasonable adjustments webpage) and describe the reasonable adjustments they require on the system.

Look to see if the person has a health and care passport (hospital passport) or communication passport as this may include information about required reasonable adjustments.

Communication passport: a document that outlines an individual’s preferred methods of communication, including details of their likes, dislikes and any specific support they require to communicate effectively. It helps ensure that communication is tailored to the individual’s needs, particularly for those with a learning disability, autism or other conditions that impact on communication.

Health and care passport: a document used to communicate essential health and care information about an individual, particularly those with complex needs, disabilities or long-term health conditions. It helps ensure that healthcare professionals and carers are aware of the person’s specific requirements, preferences and any other relevant details to provide personalised and appropriate care.

Hospital passport: a document similar to the health and care passport, but specifically focused on hospital settings. It provides essential information about a person’s health conditions, communication needs, preferences and support requirements while they are in hospital. The hospital passport ensures that hospital staff are aware of the person’s individual needs, particularly for those with a learning disability, autism or other conditions that may impact on their care.

You, as the clinician carrying out the procedure and therefore the person seeking consent, may need support; for example, from a learning disability liaison nurse or another clinician or support worker who knows the person well.

If you feel you need support in assessing capacity, your organisation’s learning disability liaison nurses and/or the MCA lead should be able to help you. You can also refer to your organisation’s policies on MCA and consent.

If you are working out of hours and the capacity decision is time sensitive and cannot wait until you can speak to the MCA lead, you may wish to seek advice from a senior colleague available out of hours (for example, nurse in charge, matron, senior on-call professional) and take a multidisciplinary approach.

An assessment flowchart is provided in Appendix 3 – a downloadable version is also available, see resources.

Lacking mental capacity: best interests decision-making

If a person is found to lack the capacity to make a specific decision in a specific timeframe, any decision made on their behalf must be in their best interests in line with the MCA.

In making a best interests decision, you must always consider:

- the person’s past and present wishes and feelings

- the beliefs and values that would likely influence their decision if they had capacity

- the views of anyone concerned with their welfare. This is often family members, carers and other relevant people (but noting these people cannot consent to or refuse treatment or care; see section on family and carers

- the least restrictive option to achieve the desired outcome; whenever possible choose this option

- any other factors the person would likely consider if they were able to do so

Any best interests decision must be properly recorded in the clinical notes.

The decision-maker (the person responsible for the treatment or action) must do whatever they reasonably can to improve the person’s ability to participate as fully as possible in any act done for them and any decision affecting them, and encourage them to participate.

Decision-makers must demonstrate that they have thought carefully about who they should consult. If it is practical and appropriate, they must consult the following people about what would be in the best interests of the person lacking capacity, and take their views into account:

- anyone previously named by the person as someone to be consulted on the matter in question or on matters of that kind

- anyone who is caring for the person

- anyone interested in their welfare (for example, family carers, other close relatives or an advocate already working with the person)

- an attorney appointed by the person under a personal health and welfare lasting power of attorney

- a deputy appointed by the Court of Protection to make decisions for the person

If decision-makers do not consult a particular person, they must be able to clearly record in the clinical notes why contact was not practical or appropriate in the notes.

Decision-makers must carefully consider the potential risks and intended benefits of any decision made on behalf of someone who lacks capacity. A balance table is a useful tool in working out where a person’s best interests lie (see Mental Capacity Act assessment form – record of decision).

Documentation and record keeping

Comprehensive documentation must be completed for all capacity assessments and best interests decisions to ensure these comply with the requirements of the MCA. It is not sufficient to simply capture in the person’s clinical record that they lack capacity to consent to treatment and there was broad discussion about what might be in their best interest.

Documentation of all assessments must detail the reasons for the decision and the supporting evidence. For best interests decisions, records should include:

- the decision made

- how it was reached

- who was consulted

- what alternatives were considered and

- why the decision is believed to be in the person’s best interests.

The individual conversations should be noted – it is not a tick box exercise.

Documentation should be simple to understand and complete.

Consent forms should clearly state that they are not used to assess capacity or best interests. If the trust uses a ‘consent form 4’ it should never be used in place of the MCA assessment form and best interests decision form. Any ‘consent form 4’ should clearly state that it is not the assessment of capacity form or the best interests decision form.

To help with assessment and documentation, we have developed a template MCA assessment form and best interests decision form (downloadable from the resources). We recommend their use for ease and for consistency across all providers of acute care. Many providers existing forms for this purpose are overly complicated and difficult for clinicians to interpret and use.

Role of independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA)

If a person who lacks capacity has no family or friends to represent them, an IMCA must be involved in decisions about serious medical treatment, and in the event the person will stay in hospital for longer than 28 days. Their role is to support and represent the person, ensuring their views, wishes and feelings are considered in decisions about them. IMCAs have the right to see relevant health and social care records.

An IMCA should also be involved if there are any safeguarding concerns regarding the family.

Information or reports from an IMCA must be considered when deciding what is in the person’s best interests.

IMCAs are appointed under the MCA and hospitals must have a process for timely referral to IMCAs. All staff who assess capacity must know how to contact IMCA services. However, accessing an IMCA must never delay urgent treatment.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS)

The MCA includes DoLS to protect people who may be deprived of their liberty in a care home or hospital setting. The safeguards ensure that deprivation of liberty is only used when necessary and is subject to review by an independent authority. DoLS orders need to be authorised by the Court of Protection.

DoLS apply to individuals aged 18 years and over who lack the capacity to consent to their care arrangements and whose liberty may be restricted to keep them safe. See box below for examples.

Restrictions that may indicate someone is being deprived of their liberty:

- continuous supervision and control: where a person’s freedom of movement is restricted by their being placed under constant observation and monitoring

- use of physical restraints: such as mittens to prevent interference with medical equipment or being placed in a chair from which they cannot get up without assistance

- administration of medication or sedation to manage a person’s behaviour, but which can limit their ability to make decisions or move freely

- restricting a person’s movement that confines them to a specific area of the ward or prevent them leaving

- a person is on a ward that is routinely locked for the protection and safety of those on the ward; and requests for their door to be unlocked are denied

In clinical practice if a person is deprived of their liberty, an assessment must take place to ensure their care is provided under the MCA legal framework. This usually involves applying for authorisation through the DoLS procedure as set out in Schedule A1 of the MHA. Where you identify a person for whom a deprivation of liberty may become necessary, you must carry out a timely assessment. An application must be made for the necessary authorisations.

MCA and 16 and 17 year olds

Given the difference in age from which the MCA and DoLS apply, there are 2 options for a young person aged 16 or 17 whose liberty is considered to be deprived by the care arrangements in place:

- where the young person lacks the capacity to consent to the arrangements in place, an application can be made to the Court of Protection for authorisation

- where the young person has not been assessed as lacking capacity but requires admission and is objecting to the admission and/or the treatment being provided, inherent jurisdiction* can be used to authorise those arrangements (see section on 16 and 17-year olds). You should consult your MCA lead and usually seek legal advice.

* Inherent jurisdiction refers to the inherent power of the High Court in the UK to decide matters where no clear statutory authority exists or where a person is deemed to lack the capacity to make decisions themselves. The court may use this power to make decisions regarding the welfare or to protect the rights of vulnerable individuals, such as those with impaired mental capacity. This jurisdiction is used particularly in cases requiring urgent or protective legal measures.

Collaboration to support assessment of capacity

When dealing with complex capacity issues, staff should collaborate with those who know the person well. As well as those below, this may include other doctors and nurses, learning disability liaison nurses and social workers. There may be other indications where staff may need to engage with relevant specialists such as neurologists or geriatricians when assessing capacity – for example, if someone has had a brain injury or is older. Trusts should have systems and procedures in place to facilitate this collaboration.

Family and carers

Family and carers of the person often know them best and will be a rich source of information about how to engage with the person and what their wishes and thoughts might be. They must be engaged and kept informed and, where appropriate, they should be offered access to support services such as advocacy and the Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS). Family and carers must always be invited to a best interests decision meeting and their voice listened to.

The family members and ‘next of kin’ of someone aged 16 or over who does not have capacity may not consent to or refuse treatment on their behalf, unless they have a lasting power of attorney for health and welfare or deputyship that specifically covers those decisions. For those who are 16 and 17 the courts have ruled that parental consent should not be relied on.

Deputies and attorneys

A welfare deputy is appointed by the Court of Protection, granting a specific individual the right to make decisions about care and treatment on behalf of a person who lacks the capacity to do so themselves.

A lasting power of attorney is a legal document held by a person to appoint one or more deputies to make decisions on their behalf in the event they lose the mental capacity to do so themselves. There are 2 types: one for financial decisions and one for health and welfare decisions. Staff should ensure at the time of admission if a LPA is in place and with whom.

Audit and review

Trusts should regularly review application of the MCA in their organisation to ensure compliance with legal standards, building this into their audit cycle and including reporting to the board.

A process should be in place for patients, families and staff to feedback on their experience of the MCA applied in practice.

16 and 17-year olds

The MCA applies to anyone aged 16 or over and therefore, 16 and 17-year-olds must be presumed to have decision-making capacity unless proven otherwise.

If a 16 or 17-year-old is identified as lacking capacity to make a specific decision, then decisions relating to medical care and treatment can be made in their best interests under the MCA.

Deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) only apply to people aged 18 or over. 16 and 17-year-olds can be deprived of their liberty using other processes. It is not possible for those holding parental responsibility to consent under any legislative framework to the deprivation of liberty of a 16 or 17-year-old. This must go to court (either the High Court if inherent jurisdiction or Court of Protection for MCA) (Birmingham City Council v D (2016) EWCOP 8, (2016) MHLO 5). You should refer to your MCA lead if you think that this situation is likely to apply.

The MCA does not apply for children aged 15 or under. Instead, assessment of their Gillick competence should be completed to determine if they can give valid consent to their medical treatment.

A child is considered Gillick competent if they have sufficient maturity and intelligence to understand the nature and consequences of the proposed treatment. This concept is important in safeguarding children’s rights in medical decisions. If they are not considered Gillick competent, consent from those with parental responsibility may be relied on to deliver medical care and treatment.

Training and awareness

In keeping with the NHS safeguarding accountability and assurance framework, all providers of NHS-funded services should ensure all staff receive safeguarding training commensurate with their role and in accordance with the intercollegiate safeguarding competencies. This includes the principles and application of the MCA.

Acute trusts should:

- have a clear training strategy and policy around MCA and ensure that this is adhered to across the organisation through auditing and reporting

- ensure that the chief executive and executive leadership team understand the MCA and champion it across the organisation, including by being visible at training events

- use simple and consistent capacity assessment and best interests documentation across the organisation. The documentation should be auditable

- develop MCA champions on every ward

Considerations for training staff on implementing the Mental Capacity Act:

- training in applying the MCA in practice should be part of the mandatory training for all clinical and other patient-facing staff and be tiered relative to their role

- one size does not fit all – adapt training to meet the context for different roles

- training should be competency based, part of reflective practice and tested periodically in line with roles and the organisation’s supervision policy

- offer ongoing training using different approaches, including on-the-job mentoring, shadowing and ward-based coaching

- application of the MCA should be discussed at Multi Disciplinary Team (MDT) or ward meetings

- a meaningful conversation about the practical application of the MCA should be included in a doctor’s annual appraisal

- the MCA should be incorporated into other training such as management and leadership training and threaded through the core business of the trust

- training should be co-produced with people with a learning disability

- training should include clinical scenarios and be interactive, involving people with lived experience where possible

- ensure there are enough skilled people to deliver high quality training around the MCA. Having MCA and learning disability champions on wards will mean that clinicians have someone on hand to ask when they need extra support

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following for their support in developing this guidance:

- Fazilla Amide, Programme Manager Learning Disability and Autism Programme – NHS England

- Charlotte Annesley, Consultant Physician and Geriatrician, Lead Physician for Adult Learning Disability and Autism Adult Learning Disability and Autism – NHS Foundation Trust

- Justine Button, Senior Specialist for People with a Learning Disability and Autistic People Care Quality Commission

- Emma Clark, Lived Experience Policy Officer Co Worker Learning Disability and Autism Programme – NHS England

- Samantha Clark, Chief Executive Learning Disability England

- Kenneth Courtenay, National Clinical Director Learning Disability and Autism Programme – NHS England

- Olivia Dodds, Admin support worker for lived experience – NHS England

- Asher Fleary-Densu, Business Support Officer – NHS England

- Chelle Farnan, Safeguarding Clinical Lead – NHS England

- Rachel Gaywood, GP and Clinical Lead Learning Disability and Neurodiversity and Representative of RCGP Special Interest Group – NHS Devon Integrated Care Board and Royal College of General Practitioners

- David Harling, Deputy Director Learning Disability Nursing – NHS England

- Elizabeth Herrieven, Consultant in Emergency Medicine – Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust

- Wendy Hicks, Policy Lead Learning Disability and Autism Programme – NHS England

- Anneliese Hillyer-Thake, Strategic Lead for SEND, Assistant Director of Nursing Safeguarding and Quality, Regional Safeguarding Lead – NHS England

- Dr Michael Layton, Consultant Psychiatrist Orbis Education and Care

- Katie Matthews, Lived Experience Policy Officer – NHS England

- Ian Maconochie, Clinical lead Children and Young People’s Programme – NHS England

- Sam Othen, National Safeguarding Lead Nuffield Health

- Katharine Petersen, Co-chair special interest group for learning disability, RCGP. Royal College of GPs

- Sam Rogers, Policy Lead Race Health Observatory

- Elaine Ruddy, Safeguarding Transformation and Policy Lead – NHS England

- Dan Scorer, Head of Policy, Public Affairs, Advice and Casework Mencap

- Nikki Sidgwick, Clinical Lead Mental Capacity Act and Safeguarding – NHS England

- Jo Skinner, Senior Communications and Engagement Manager – NHS England

- Aaron Senior, Learning disability advisor – NHS England

- Rachel Snow-Miller, Head of Health Improvement, Learning Disability and Autism – NHS England

- Anne Worrall-Davies, Clinical Lead Learning Disability, Autism and SEND Learning Disability, Autism and SEND

- Helen Watson, Director of Allied Health Professionals Cambridge University Hospitals Foundation Trust

- Philip Winterbottom, Head of Safeguarding and Protection – Chair Cygnet Health and National Safeguarding Network for Independent Providers

Appendix 1: Advice on how to undertake the 2-stage test for mental capacity

Stage 1

Question:

Understanding: can the person understand the information relevant to the decision?

Supporting prompts:

- Explain why you are assessing their mental capacity to make the decision and the decision you will make based on this

- Has the individual been given all the information they need to help them make the decision?

- Use simple language: avoid jargon and complex terms. Break down information into manageable parts

- Visual aids – diagrams, pictures – or written notes to help explain concpets

- Identify the key details that the person needs to understand

- Check their comprehension: ask open-ended Instead of yes/no questions, ask them to explain the information in their own words – for example, “Can you tell me what you understand about this treatment?”

- Summarise and reflect: summarise what the person has said and ask them if you have correctly This helps confirm their understanding

- Repeat and rephrase: repeat important information and rephrase it if necessary. This can help reinforce understanding

- Use different approaches: if the person is struggling to understand your explanation, try a different method or analogy

Question:

Retaining: can the individual retain that information for long enough to make a decision?

Supporting prompts:

- Short-term recall: after a brief period, ask the person to recall the information. This checks if they can retain it for long enough to make a decision

- Prompting: provide gentle prompts if needed, but don’t compromise the person’s ability to show they can recall the core information independently

- MCA 2005 section 3(3) states that people who can only retain information for a short time must not automatically be assumed to lack the capacity to make decisions – it depends on what is necessary for the decision in question

- Tools such as notebooks, photographs, posters, videos and voice recorders can help people record and retain information

Question:

Weighing up: can the individual use or weigh up the information as part of the decision- making process?

Supporting prompts:

- Ensure the individual has been given clear details of the choices available to them and the implications of each option (the risks and benefits). Ask them to consider the pros and cons of the different options: “What do you think are the benefits and risks of this choice?”

- Consider if the individual is being influenced by the views of others

- An individual’s inability to reach a decision could indicate they cannot weigh up the information

- If the individual can describe the risks and benefits of each option but cannot relate these to their circumstances, they could be deemed unable to weigh up the information

Question:

Communicating: Can the individual communicate their decision?

Supporting prompts:

- Be aware of the individual’s communication needs and make reasonable adjustments

- Decisions can be communicated by any means possible – for example, verbal or sign language, gesture, drawing, writing

Stage 2

Question:

The ‘diagnostic test’: is the person’s inability to make the decision the result of an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain?

Supporting prompts:

- The impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain can be temporary or permanent, and can manifest in signs and symptoms such as confusion, drowsiness and concussion. Drug or alcohol abuse can also affect functioning.

- Stage 2 is sometimes referred to as the ‘diagnostic test’ but this can be misleading because a formal diagnosis of an impairment or disturbance is not always necessary, providing there is clear evidence of such.

- It is not sufficient for the assessor simply to state that the person has a disturbance or impairment of mind. They need to show how this disturbance or impairment of mind means it impossible for the person to make the decision(s) in question. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘causative nexus*’.

- Is the impairment or disturbance in the functioning of mind or brain temporary or permanent?

* In the context of mental capacity assessments, a ‘causative nexus’ refers to the direct, demonstrable link between a person’s mental impairment or disturbance and their inability to make a specific decision. Please refer to:

- Supreme Court decides the test for capacity to engage in sexual relations – 39 Essex Chambers

- Understanding the causative nexus – Mental Capacity Ltd

A PDF version of this advice is available.

Appendix 2: Checklist for preparing to assess the mental capacity of someone with a learning disability

Think about the person being assessed

1. Do they have health issues that may affect their concentration (for example, flu)?

2. Is this the best time of day to assess their capacity? Some people concentrate better at certain times of the day and religious observances may have an impact.

3. Are they taking medication that could affect their concentration during the assessment?

4. Have you set aside enough time to do the assessment at the pace that works for the person and to answer their questions? You can have a second conversation with someone to make sure that they have understood what you are talking to them about.

5. Has a significant event occurred recently in their life (for example, bereavement/changing accommodation) or a more subtle event (for example, being upset by a friend)?

Communications needs

6. How does the person usually communicate? (for example, Makaton, their first language, assistive technology)

7. Does the person usually access assistance from others? If so, could that person be present during the assessment? If not, who can assist you in this situation?

8. Does the person need someone to sign or interpret for them? If so, arrange for an interpreter or signer to be present.

9. Does the person use hearing aids or glasses? If so, check they are wearing them before the assessment.

10. Have you prepared how you will give information in simple language when carrying out the assessment, avoiding jargon or acronyms? You may want to prepare communication aids such as Easy Read information or pictures to help you explain a procedure.

11. Has the person or their family/carer asked for more information or information in a different format, and have they been given it?

Environment

12. Is the environment where you will carry out the assessment free from noise and distractions?

A PDF version of this checklist is available.

Appendix 3: Mental Capacity assessment flowchart

A PDF version of this flowchart is available.

Additional resources

- reasonable adjustments that can support assessment of capacity of people with a learning disability

- template forms for recording mental capacity assessment and best interests decision including balance tables

- Mental Capacity Act assessment poster (below)

A PDF version of this poster is available.

Publication reference: PRN01699