Best practice timed diagnostic pathways

Best practice timed pathways support the ongoing improvement effort to shorten diagnosis pathways, reduce variation, improve patient experience of care, and meet the Faster Diagnosis Standard (FDS). The guidance will support cancer alliances and constituent organisations to adopt consistent, system-wide approaches to managing this diagnosis pathway.

This guidance sets out how diagnosis within 28 days can be achieved for the suspected oesophago-gastric cancer pathway. Alongside the pathway itself, resources are highlighted to support implementation of the pathways.

This oesophago-gastric pathway is part of a series, published since April 2018. From previous pathways implemented by cancer alliances, implementation guidance was shared in June 2021, identifying areas that are key to success, such as setting up with clinical and operational engagement, auditing pathways, allocating project management resources, ensuring leadership, analysing data, and sharing successes.

This guidance complements existing resources such as NICE guidelines (including NG12) and should therefore be read alongside such guidance. While the guidance stipulates recommended clinical actions and timings, we recognise that this will not apply to all patients in all circumstances, and that responsibility for clinical decision making remains with local clinical teams with the knowledge and expertise to make appropriate decisions and policies.

The pathway in this document was developed by a multidisciplinary consensus group with clinical leaders from local and specialist services across England, and expert advice from cancer alliances including:

- Cheshire and Merseyside

- Greater Manchester Cancer

- Northern

- RM Partners

- Thames Valley

- UCLH Cancer Collaborative.

For questions about this document, please email England.CancerPolicy@nhs.net.

Dame Cally Palmer, National Cancer Director, NHS England

Professor Peter Johnson, National Clinical Director for Cancer, NHS England

Mr William Allum, Oesophago-gastric Representative for Clinical Advisory Group, NHS Cancer Programme

The Faster Diagnosis Standard

We committed in the NHS Long Term Plan to provide a faster diagnosis for people through the introduction of the Faster Diagnosis Standard (FDS). This standard will ensure people are told they have cancer, or that cancer is excluded, within a maximum of 28 days from referral. The new standard is intended to:

- reduce the time between referral and diagnosis of cancer

- reduce anxiety for the cohort of people who will be diagnosed with cancer or receive an ‘all clear’

- reduce unwarranted variation in England by understanding how long it is taking people to receive a diagnosis or ‘all clear’ for cancer

- represent a significant improvement on the current two-week wait to first appointment target, and a more person-centred performance standard.

FDS performance data, including a breakdown by suspected cancer pathway, has been published since June 2021. Faster, more streamlined pathways will be a priority.

As the key system-wide organisations for cancer services, cancer alliances will need to work across the local system to ensure that implementation is prioritised by senior stakeholders, clinical leaders, and operational colleagues, and that capacity is prioritised to enable the standard to be delivered.

The FDS has been formally performance-managed since October 2021 activity, in line with cancer services recovery, with an initial threshold of 75%, rising to 80% in 2025/26. Cancer alliances will need to ensure that they have plans to meet the threshold, which will need to be increased in subsequent years if we are to contribute to achieving the early diagnosis ambitions in the NHS Long Term Plan.

The case for change

- Oesophago-gastric cancer is the fifth most common cause of cancer in the UK, affecting more than 11,000 people each year.

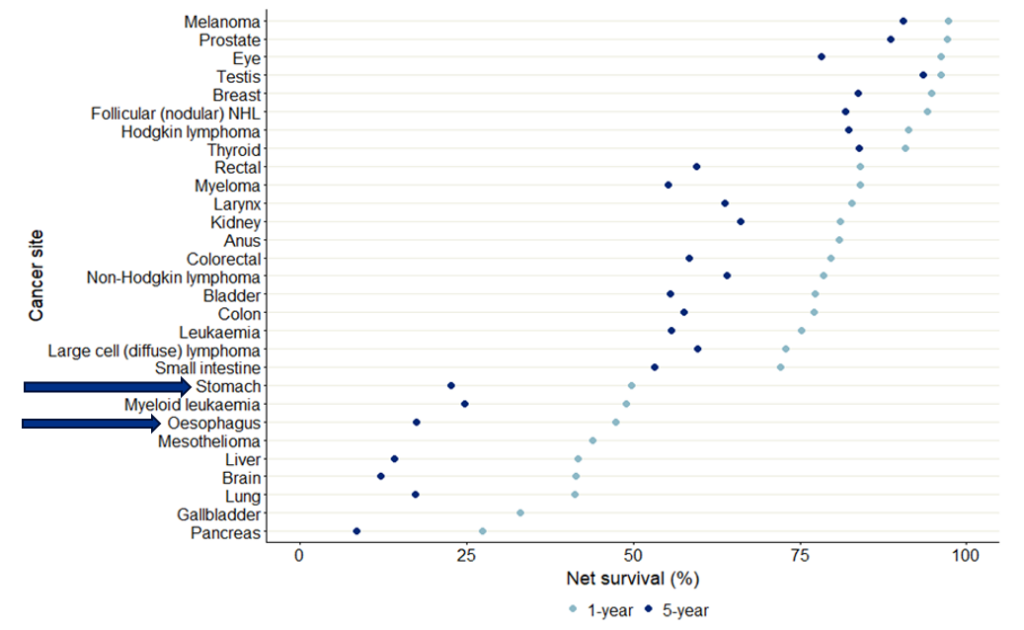

- For oesophago-gastric cancer male patients in England diagnosed between 2016 and 2020, one-year age-standardised net survival was 47.4% for oesophageal cancer and 49.8% for gastric cancer.

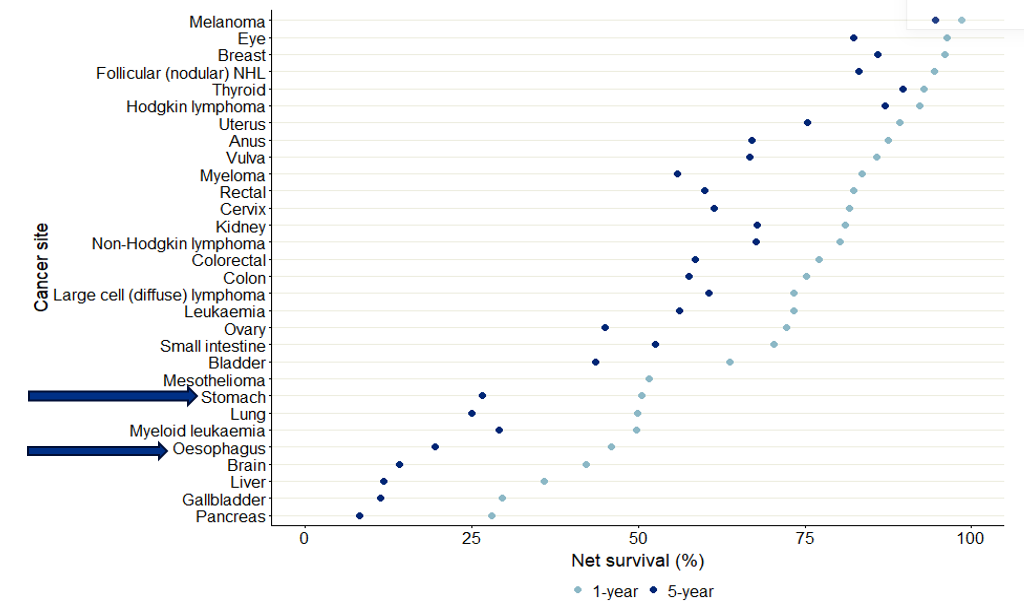

- For oesophago-gastric cancer female patients in England diagnosed between 2016 and 2020, one-year age-standardised net survival was 45.9% for oesophageal cancer and 50.5% for gastric cancer.

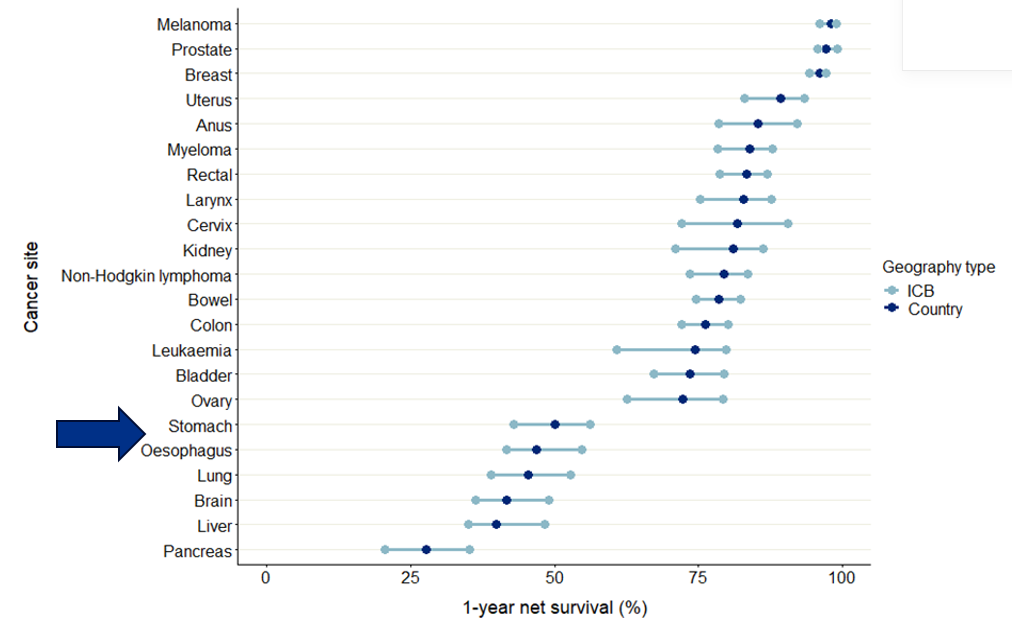

- In 2020, only 5% of oesophagus cancers and 16% of gastric cancers were diagnosed at stage one. This varied at sub-integrated care board level with a range of 1% to 26% for oesophagus cancers and 3% to 67% for gastric cancers.

- Patients with oesophago-gastric cancer have some of the poorest outcomes and longest intervals between referral and commencement of treatment among all cancers in England at present.

A streamlined and more efficient pathway will reduce overall waiting times, avoidable delays and considerable variation. Alongside adopting the best practice timed pathway, cancer alliances must ensure the appropriate resources and capacity are in place to deliver high-quality services to more patients.

Figure 1: Age-standardised 1-year and 5-year net survival for males (aged 15 to 99 years) diagnosed with cancer in the period 2016 to 2020 and followed up to 2021

Source: National Disease Registration Service

Figure 2: Age-standardised 1-year and 5-year net survival for females (aged 15 to 99 years) diagnosed with cancer in the period 2016 to 2020 and followed up to 2021

Source: National Disease Registration Service

Figure 3: Age-standardised 1-year net survival (%) for adults diagnosed in the period 2016 to 2020 and followed up to 2021, and the site-specific variation of survival estimates for ICBs

Source: National Disease Registration Service

Actions for cancer alliances

In 2023/24, all systems were asked to develop plans to:

- Implement and maintain priority pathway changes.

- Increase and prioritise diagnostic and treatment capacity, including ensuring that new diagnostic capacity, particularly via community diagnostic centres (CDCs), is prioritised for urgent suspected cancer.

- Maximise the pace of roll-out of additional diagnostic capacity, delivering the second year of the three-year investment plan for establishing Community Diagnostic Centres (CDCs) and ensuring timely implementation of new CDC locations and upgrades to existing CDCs.

- Deliver a minimum 10% improvement in pathology and imaging networks productivity by 2024/25 through digital diagnostic investments and meeting optimal rates for test throughput.

- Increase GP direct access in line with the national rollout ambition and develop plans for further expansion in 2023/24

NHS England provides support, funding and guidance to help cancer alliances improve outcomes and reduce variation. The following support is available:

- Funding and programme management to support delivery to achieve the FDS and best practice timed pathway milestones.

- Implementation guidance for achieving pathways.

- Collaboration and networking events to share best practice.

“The patient pathway from referral to decision to treat for oesophageal or gastric cancer is one of the most complex cancer pathways. The combination of endoscopy and biopsy, CT and PET-CT imaging, interventional staging and comprehensive comorbidity assessment highlights this complexity. Unlike other more common cancers, the initial diagnostics are undertaken at local units and the more invasive staging investigations require specialist decision and intervention.

“The key features of this pathway are to improve the streamlining of the transfer between local unit and specialist centre with defined responsibility for the respective steps. This should be integrated with timely booking and reporting of the diagnostic and staging investigations. It is expected that once a decision is made at the local unit to refer to the specialist centre, a booking for the PET-CT (if indicated) should be made so it is available for the specialist multidisciplinary team meeting.

“The proposed changes are simple but do require better administration of existing pathways. Their implementation is anticipated to reduce waiting times for critical investigations and decision making and enable prompt starts for treatment for those diagnosed with oesophago-gastric cancers.”

William Allum, Oesophago-gastric Representative for Clinical Advisory Group, NHS Cancer Programme.

Benefits of pathway change

For patients and unpaid carers

- Reduced anxiety and uncertainty of a possible cancer diagnosis, with less time between referral and receiving the outcome of diagnostic tests.

- Improved patient experience from fewer visits to the hospital, particularly to specialist centres if possible, and avoiding emergency admission.

- Potential for earlier recognition and initiation of pre-optimisation for treatment that could reduce complications and adverse outcomes.

For systems

- Reduced demand in outpatient clinics with increased straight to test provision and use of pathway navigators.

- Allow resources to be targeted at patients with cancer by removing non-cancer patients earlier in the pathway.

- Improved quality, safety, and effectiveness of care with reduced variation and improvement in outcomes.

Experience of care

- Patients and carers know they are urgently referred for investigation of suspected cancer and should expect diagnosis within 28-days.

- Ensure that patients and carers’ ability to attend appointments is taken into account and additional support is offered, where necessary.

- Patients are communicated with clearly, understand the information provided, and are given additional support, such as access to a CNS or navigator, psychological support, buddy system, where necessary.

For clinicians

- Using a nationally agreed and clinically endorsed pathway to support quality improvement and reconfiguration of oesophago-gastric cancer diagnostic services.

- The use of predetermined diagnostic algorithms and standards of care to streamline clinical decision-making and reduce delays for multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion.

- Improved ability to meet increasing demand and ensure best utilisation of the highly skilled workforce.

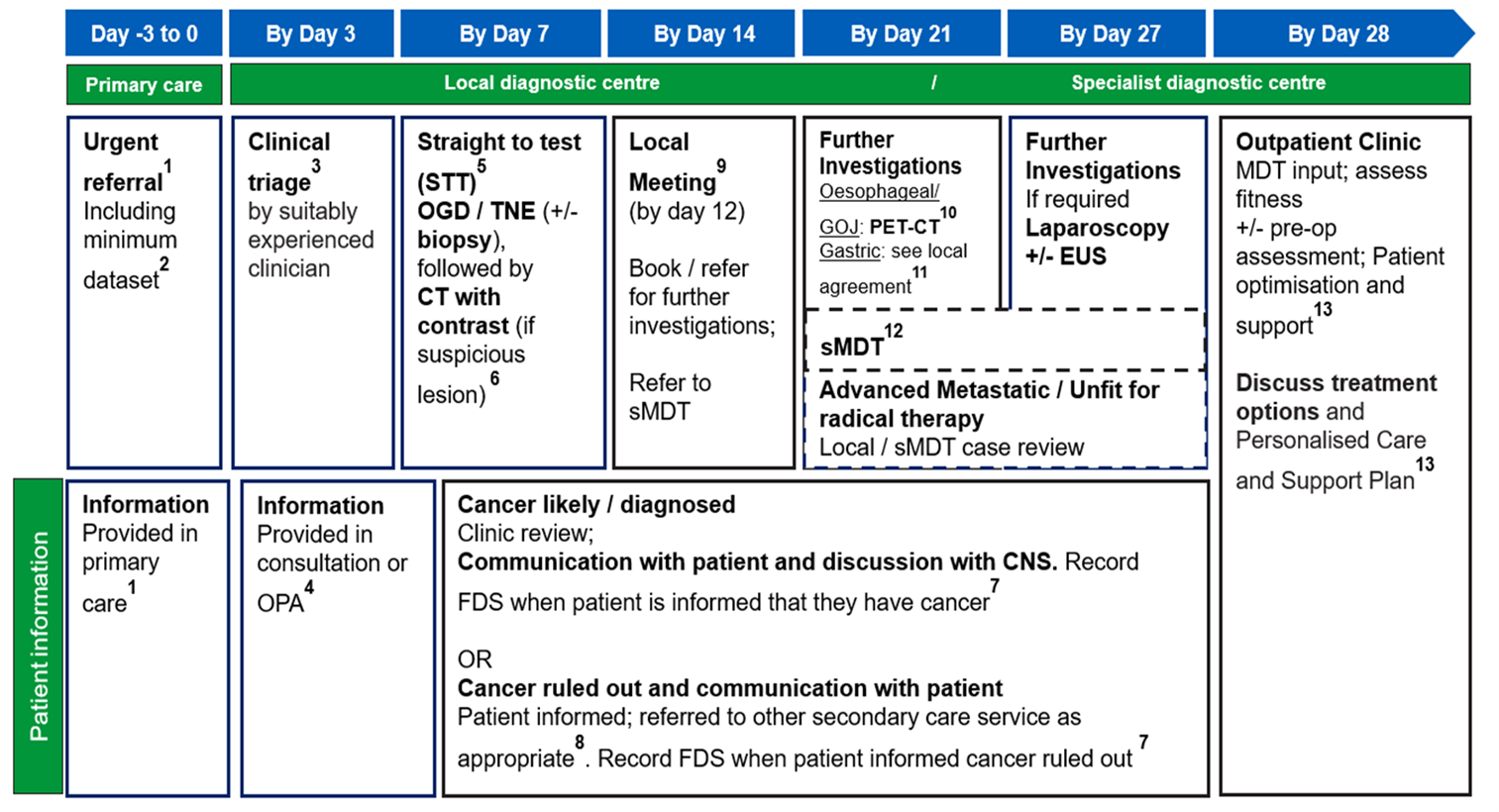

28-day best practice timed pathway

For footnotes/references, see ‘detailed information’ section.

Detailed information

1. This pathway should be used for patients who meet NG12 criteria for suspected cancer pathway referrals. In a scenario where the GP refers the patient for a direct access test and the upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is abnormal and suspicious of cancer, patients should be followed up by secondary care directly from endoscopy (without the need for an additional referral from their GP). The patient would then join the pathway after the first diagnostic test (labelled on this pathway diagram as ‘straight to test’.

The National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Dataset Guidance v11.0 sets out these rules. cancer alliances may set out local arrangements to facilitate patient access to this pathway. Information to be provided by primary care to the patient includes information about FDS, urgent suspected cancer pathway and expected timelines, including responsibilities to make themselves available for the first seven days for full diagnostic testing.

2. A minimum dataset should be agreed locally with GPs, to accompany the referral and facilitate straight to test and immediate CT scan, which includes:

- patient demographics

- FBC

- eGFR

- anticoagulant status

- performance status

- co-morbidity

- medication

- need for interpreter

- mental capacity to consent.

There should be a locally agreed nutritional assessment tool (eg MUST assessment with referral for dietitian assessment if score 2 or greater).

3. Clinical triage can be done by a suitably experienced clinician. This may be a supervised CNS. If a patient is medically unfit for straight to test, patient should be reviewed in clinic. If deemed medically fit, the appropriate first line investigation of contrast CT should be performed and reported within five days of triage so that this cohort can progress on the pathway in the same timeframes. Patients should have same day investigations to reduce repeat visits and improve patient experience.

Telephone or video consultation could be used to determine suitability for straight to test and pre-assessment. Preparation for any tests can be communicated to patients at this stage. A clinical assessment service (CAS) to prioritise referrals will support patients to be referred to the correct clinic or test, and ensure that appropriate pre-investigations have been carried out.

4. Patients and care-givers should be asked what information they require about the pathway, provided with standard leaflets about investigations when sending confirmation of appointment, confirmation of next step(s) and any patient needs required to prepare for the day (for example, can they eat and drink before), and whether they have any disabilities or language barriers.

Preferences for amount of information and when it is provided will vary, and therefore it will help to provide caseworker/navigator telephone contact details to provide support throughout the pathway and outside of clinic times, provide signposting to charities and support services, provide information about care-givers attending appointments, and offer follow-up if patients do not receive confirmation of appointment in expected timescale.

Where possible, continuity of caseworker/navigator should be provided to enable familiar contact and to build trust. Patients should also be informed that it is likely they will receive a procedure and/or diagnostic test on the same day at the first face to face appointment.

5. OGD should be performed to BSG/AUGIS quality standards to minimise false negative or inadequate biopsies, and trans-nasal endoscopy (TNE) to the same high quality and safe manner as set out by the Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy. Histology results taken during endoscopic procedures should be reported within 72 hours of the biopsy. In the cohort of patients who are medically unfit for straight to test, the recommended first line investigation should be contrast CT. This should be performed and reported within five days so that this cohort can progress on the pathway in the same timeframes.

6. If a suspicious lesion is identified, patients should have access to a CNS with expertise in oesophago-gastric cancer for support (from this stage onwards). Patients should have CT within 24 hours. This should be reported within 72 hours, ideally by a radiologist with an established gastroenterology interest.

7. Patients should be informed about cancer being ruled out, or diagnosed at the earliest face-to-face opportunity, unless the patient has expressed an alternative method of communication in order to speed up communication. In this timed pathway, this can be done at a testing clinic, a follow-up testing or results outpatient appointment. Early consideration of patient’s fitness for radical therapy and requirements for pre-habilitation should be addressed as soon as possible in the pathway to minimise delays in expediting treatment.

All patients diagnosed with cancer should have a referral to relevant allied health professionals (AHPs), including a specialist dietitian within seven calendar days of diagnosis, and where required, will also be involved during treatment planning. Local protocols and initiatives should be developed in collaboration with perioperative medicine, elderly care and specialist dietitians. Cancer waiting time rules (including ‘clock start’, ‘adjustments’ and ‘clock stop’) are set out in the National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Dataset Guidance v11.0

8. Where cancer is ruled out, in some cases it would be appropriate to provide an MRI or CT before onward referral to a non-cancer routine pathway. Where cancer is excluded or confirmed, the FDS ‘clock stop’ can be completed at this point of communication with the patient. When oesophago-gastric cancer is ruled out, but other cancers are not, it may be appropriate to refer the patient on to an alternative tumour site specific pathway, or a rapid diagnostic centre pathway, where non-specific or vague symptoms can be considered. There are significant ‘overlap’ for upper GI symptoms, so for anyone aged 55 or over with weight loss and upper abdominal pain, reflex or dyspepsia, the patient should have an OGD / TNE and if cancer is ruled out, followed by a CT of pancreas as standard, when referred on a suspected cancer pathway to Upper GI teams.

9. ‘Local meeting’ in the context of this pathway is a local unit MDT where these exist. The core roles at the local meeting are lead clinician, radiologist and pathologist, to review investigation results with a pathway navigator. An oncologist with an interest in oesophago-gastric cancer and a radiologist with an established gastroenterology interest should be present at the Local Meeting. The capacity required to deliver these core roles should be reflected in job plans.

Patients considered suitable for radical therapy should be booked (or referred) for appropriate staging tests as set out in the pathway, and should also be referred directly to the specialist multidisciplinary team (sMDT). Input of sMDT clinicians to local meetings (eg via videolink) can facilitate faster staging decisions.

10. For oesophageal/GOJ cancer: PET-CT should be performed in line with the NICE quality standard on oesophago-gastric cancer, which includes a seven-day standard from requesting to reporting. Further investigations could be provisionally booked at the same time as PET-CT is booked (as part of a predetermined standard of care to reduce delays) or booked into dedicated weekly slots available to perform these tests within seven days of the PET-CT report. Laparoscopy +/- EUS should not be performed until the PET-CT report is reviewed by the sMDT, and EUS should only be used in select cases where it will help to guide ongoing management.

11. For gastric cancer: Protocols should be developed collaboratively between local units and specialist centres for gastric cancer staging. A subset of suspected gastric cancers may be suitable for direct referral to specialist centre for laparoscopy and this may be agreed across a cancer alliance level as part of a predetermined standard of care. Other cases may need sMDT review to determine most appropriate staging, in which case the sMDT should take place as soon as possible to determine a complete diagnostic plan.

12. The core membership of the sMDT must align to the relevant NHS England service specification for oesophago-gastric cancer (specialised commissioning) (2013). As a minimum, the sMDT meeting should include a radiologist and oncologist who both have a specialist interest in oesophago-gastric cancer, in line with the NICE quality standard on oesophago-gastric cancer (2018). Investigation results should be reviewed with a pathway navigator or co-ordinator. The capacity required to deliver these core roles should be reflected in job plans. National guidance on how to maximise effectiveness of MDT meetings (2019) is available.

Patients considered suitable for radical therapy should be booked (or referred) for appropriate staging tests as set out in the pathway, and should also be referred directly to the sMDT. Input of sMDT clinicians to local meetings (eg via videolink) can facilitate faster staging decisions. Locally agreed, clear criteria for referral to sMDT can also support with efficient pathway management.

One example of how the sMDT could be managed for the oesophago-gastric pathway is to have a pre-MDT triage process at the specialist centre (to review referral +/- PET-CT and identify the required further staging tests), with the full sMDT taking place following these further investigations. Another example would be to hold a full sMDT at time of review of PET-CT, where treatment options would be pre-agreed based on the potential outcome of further investigations.

13. Personalised care and support planning should be based upon the patient and clinician(s) completing a holistic needs assessment (HNA), usually soon after diagnosis. The HNA ensures conversations focus on what matters to the patient, considering wider health, wellbeing and practical issues in addition to clinical needs and fitness. This enables shared decision-making regarding treatment and care options.

Additional information

Audit tool

Can be used to undertake a baseline audit of services being delivered and whether sufficient capacity is in place to routinely deliver, identify areas for improvement, select measurements for improvement, and conduct re-audits as part of continuous improvement.

| Day | Pathway step | Service in place? | Capacity in place? |

|---|---|---|---|

|

-3 to 0 |

GP referral: Local agreements with primary care should be in place to ensure the minimum dataset is provided (as detailed in pre-referral information), to facilitate straight to test provision. | ||

|

Patient information resources should be co-developed with patients. | |||

|

3 |

Clinically led triage should be consultant supervised and delivered by an appropriately trained clinician (eg CNS); local protocols need to be in place to reduce delays (eg management of anticoagulants). | ||

|

7 |

Straight to test provision for all eligible patients: Consider pooled lists and networking arrangements to maximise efficiency. Try to ensure endoscopists for patients on this pathway are experienced in oesophago-gastric cancer diagnostics, and perform to BSG/AUGIS quality standards to reduce re-scope/inadequate biopsy rate. Histology results taken during endoscopic procedures should be reported within 72 hours. | ||

|

CT: Ensure processes are in place to book from endoscopy suite; consider dedicated slots to ensure same/next day scan. | |||

|

12 |

Local Meeting: Consider pathway navigator/co-ordinator and dedicated clinician time to facilitate process effectively. Protocols and pathways should be agreed between local and specialist centres to ensure patients can be booked for appropriate further investigations and referral to sMDT without delay. | ||

|

14 |

Outpatient Clinic: Ensure the patient is informed of likely diagnosis before they are contacted by the specialist centre for further appointments. Agree protocols for pre-assessment with the specialist centre, and protocols on optimisation that can be initiated locally to provide early opportunities for optimisation (eg smoking cessation and nutritional support). The patient should also have an opportunity to meet the specialist dietitian +/- local CNS. | ||

|

The CWT system will record ‘referral request received date’ as part of the inter-provider transfer to the specialist centre. This data item can be used to audit pathway implementation, aiming to refer the patient to the specialist centre by day 14. | |||

|

12 to 21 |

Further investigations: Consider role of pathway navigators/co-ordinators and dedicated clinician time to facilitate early sMDT (if required) and review of PET-CT report prior to expedition of further staging investigations. | ||

|

21 |

sMDT for review and planning of potential treatment options- where laparoscopy (or other further investigations) is required after staging then full sMDT discussion may need to be deferred until day 28, in which case provision for same-day clinic review with results should be considered. Alternative treatment options may be pre-agreed based on potential outcome of further tests. | ||

|

28 |

Outpatient Clinic: Cancer confirmed and treatment options discussed. A multidisciplinary clinic with surgeon, oncologist, anaesthetist and AHPs – such as therapeutic radiographer, speech and language therapist and specialist dietitian – should be considered. This aims to improve patient experience, improve communication, and prevent delays in starting treatment. |

Resources

- The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) provides details of a five-step score to identify patients who are malnourished, at risk of malnutrition, or obese. It also includes management guidelines which can be used to develop care plans.

- Quality standards in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a position statement of the BSG and AUGIS sets out the minimum expected standards in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (including 38 recommendations).

- NICE guideline (NG83) – Oesophago-gastric cancer: assessment and management in adults covers assessment and management of oesophago-gastric cancer in adults including radical and palliative treatment and nutritional support.

- NICE quality standard (QS176) – Oesophago-gastric cancer sets out best quality care in four areas of management for patients with oesophago-gastric cancer.

- Guidelines for perioperative care in esophagectomy: enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS®) society recommendations sets out a guideline on multidisciplinary care following surgical procedures, recommending guidelines to improve outcomes and quality for oesophageal resection.

- Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy sets out recommendations for post-operative care of patients who have had gastrectomy, with evidence of improved outcomes.

- NHS England’ personalised care resources can support you to ensure patients have choice and control over the way their care is planned and delivered. It is based on what matters to the patient and individual strengths and needs.

- NHS England’s Change Model is a framework for any project or programme seeking to achieve transformational, sustainable change (refreshed on 4 April 2018).

- NHS England’s Improvement Hub provides a number of useful resources that can support service improvement including guidance, modelling tools, and webinars.

- The Delivering Cancer Waiting Times – A Good Practice Guide sets out good practices to achieve and sustain CWT performance.

Cancer alliance workspace

Cancer alliances access this workspace for national guidance, resources, and to share learning. Please use this space to upload materials you have developed locally and that you think would be useful for colleagues implementing this pathway across the country.

Acknowledgements

This guidance was developed by the NHS Cancer Programme and builds on experience and expertise provided by the National Cancer Vanguard (George Hanna, Sarah Adams, Jonathan Vickers, James Leighton, Dip Mukherjee, Jake Goodman, Caroline Cook, Kathy Pritchard-Jones, Dave Shackley, Nicholas Van As), members of the consensus group (William Allum, Jonathan Booth, Lily Megaw, Guy Mole, Anna Murray, John Painter, Sheron Robson, Arun Takhar, Nigel Trudgill, Andrew Veitch, Arnold Victor, Chris Warburton), Tony Newman-Sanders as National Clinical Director for diagnostics and imaging, and Robert Logan as National Endoscopy Advisor.

Publication reference: PRN1349