The NHS Long Term Plan states that digital-first primary care will become a new option for every patient, improving fast access to convenient primary care. Digital health is a broad and growing area of medicine that includes categories such as mobile health (mHealth) in the form of smart devices, apps, and wearables; health information technology; telehealth; and personalised medicine.

The NHS Long Term Plan envisages a move towards digitally enabled services with integrated models of care. This has the potential to transform healthcare, bringing the point of care from the clinician to the patient. Greater use of digital health tools and connected medical devices is central to the vision.

What is a medical device?

A medical device is any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, material, or other article, which is intended for human use that performs a medical purpose, such as diagnosing, monitoring, or treating a medical condition. This could be hardware, software, or appliances ranging from sticking plasters to defibrillators. Medical devices include anything used for:

- diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment, or alleviation of disease

- diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation of or compensation for an injury or disability

- investigation, replacement, or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological process

- control of conception

Medical devices already are a routine part of general practice, for example:

- provision of physical medical devices, e.g. glucose monitors, blood-pressure machines

- implantable medical devices inserted in primary care, e.g. coils, catheters, and implants

Increasingly, medical devices are arriving in new forms, for example:

- in the form of software or apps, e.g. apps to manage medical conditions, apps to enable telehealth

- information patients present through apps or self-bought devices

- new connected medical equipment, e.g. blood pressure machines, or 2-6 lead ECG devices to screen for atrial fibrillation

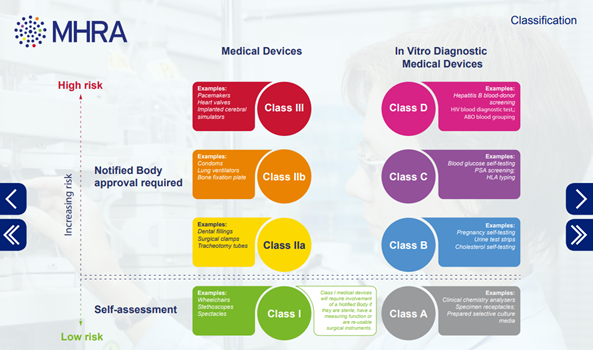

Classification of medical devices

General medical devices

When a product has been established as a general medical device, it is classified based on risk. The risk depends on factors including the intended purpose, duration of use, and whether it is invasive, implantable, active, or contains a medicinal substance. The categories are:

- Class I – generally regarded as low risk

- Class IIa – generally regarded as medium risk

- Class IIb – generally regarded as medium risk

- Class III – generally regarded as high risk

Accessories to medical devices are classified separately to the device. All active implantable medical devices and their accessories fall under the highest risk category (Class III).

In vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDs)

In vitro diagnostic medical devices include all tests, including lab tests, point of care tests and ‘self-test’ devices intended to be used by a person at home. These are categorised differently into 4 main groups.

Detailed information aimed at suppliers on how to classify medical device and what regulations are required can be found at the following links:

- Medical devices: how to comply with the legal requirements in Great Britain

- Medical devices regulation and safety: detailed information

- Medical devices: software applications (apps) (information on when software applications are a medical device and how they are regulated)

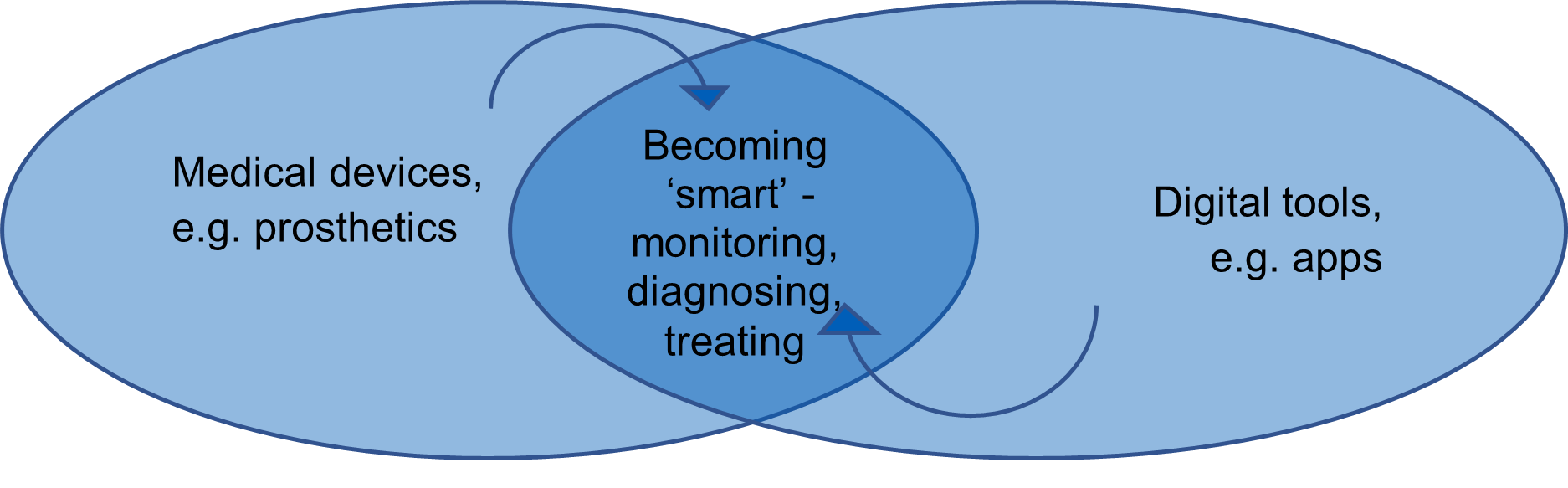

Medical devices and digital connectivity

Medical devices are increasingly able to generate data and connect to consumer technology. This convergence of medical devices with mobile health enables patients to be better informed than ever before in managing their conditions. It also allows clinicians to monitor patients with real time data without the patient leaving their home.

As medical devices become connected via the internet, they require special consideration of the novel risks this creates regarding the need for secure internet access, software reliability, privacy, and cyber security.

There is also an increasing need to consider the risk of the digital exclusion of those who may not have the connected devices, internet connection or skills to benefit from digital connectivity.

Digital tools that may be medical devices

Digital health tools that may be medical devices include:

- patient facing apps that enable self-management or remote monitoring of medical conditions such as diabetes or depression

- symptom checkers that offer medical advice based on information entered by a patient

- online digital tools to assist in diagnosis, e.g. a cloud-based software program that identifies melanomas from dermatoscope images

- an app that advises on insulin dose based on a diabetic patient’s blood glucose level and dietary input

- medical calculators and algorithms

Medical devices becoming connected

Examples of primary care medical devices now becoming connected include:

- a blood pressure machine that transmits results to a mobile phone to be analysed and offers advice to the patient

- a six-lead ECG that automatically connects to an app that can share the recording with a cardiologist

Prescribing and medical devices

The General Medical Council (GMC) states that doctors must take the same care when recommending medical devices and digital health tools as they do when issuing traditional prescriptions. As with prescribing medication it is important to ensure that any medical device or digital health tool you recommend is safe, indicated, effective, and regulated so that any risks are mitigated. The GMC Good medical practice guide states that in providing clinical care you must only ‘provide effective treatments based on the best available evidence’.

Information for users and patients

It is important for clinicians to ensure that patients have adequate information and training in using medical devices, and to be aware that patients may be using self-bought medical devices bought online or downloaded as apps from app stores. These could include blood glucose meters, blood pressure monitors, condoms, contact lenses, pregnancy and other self-test kits, wheelchairs, or baby breathing monitors.

If purchased in the UK an item should be subject to the same regulation of medical devices.

Patients may or may not be using them as their manufacturer intended, so it is always worth checking, as off-licence or improper use could result in unreliable results and introduce new risks.

Before buying a medical device, patients should:

- make sure it is suitable for their medical condition

- check it has CE marking, UKCA marking, or CE UKNI marking

- check if the manufacturer’s address is on the device or the packaging

- get a demonstration of how to use the device – especially if it’s a complicated device or procedure

- know what to do if the device is faulty or not working as it should

Before using a medical device, patients should:

- check the device is not damaged

- make sure they understand and follow the instructions

- register the device with the manufacturer so that the manufacturer can contact them if there is a fault or safety problem with the device

- make sure they have everything they need, for example, find out if the device needs anything else to make it work such as test strips, batteries and so on

- keep the device in good condition by following instructions about service and maintenance and keep a record of the service history

- store the device according to the manufacturer’s instructions – for some devices the wrong temperature or humidity can affect how it works or give you wrong results

The Government provides more detailed information for users and patients.

Health apps

There are over 325,000 health apps available to members of the public for download from app stores. They are produced across global jurisdictions, and the number increases by hundreds each day. The sheer number, variety, complexity, and pace of change makes regulating them a formidable challenge.

Good digital general practice must navigate this challenge and help patients access high quality digital tools in a joined-up way. App libraries and app accreditation services such as Orcha, and the NHS Digital Technology Assessment Criteria (DTAC) can help.

The NHS has moved away from the branded NHS apps library and instead is highlighting apps on condition-specific pages of NHS.UK.

Virtual reality and augmented reality

Virtual reality (VR) is a three-dimensional, computer-generated environment which can be explored and interacted with by a person. That person becomes immersed within this environment and can manipulate objects or perform actions.

Augmented reality (AR) is similar but integrates digital information with the user’s environment in real time.

Both VR and AR can be used in medical education, imaging, and training. Their uses include:

- simulation of consultations, medical procedures, or emergencies

- as new ways of doing online consultations or group consultations which provide novel ways of engaging with patients

- as therapeutic devices, for example to help a patient overcome a phobia, such as needle phobia, by graduated exposure to the cause

There could be many other applications.

The safety, privacy and digital exclusion considerations of VR/AR are like other medical devices and digital tools and need to be considered.

Legislation and regulation of medical devices

The legislation of medical devices that applies in Great Britain is complex and has been affected by the UK leaving the European Union or EU.

The UK Conformity Assessed (UKCA) mark is a new UK product used to identify goods being placed on the market in Great Britain. Products may also carry the CE mark to show conformity with European health, safety, and environmental protection standards. The standards are currently similar, although stand to diverge over time.

Medical devices in the UK are regulated by the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The MHRA performs market surveillance of medical devices on the UK market and can take decisions over the marketing and supply of devices in the UK.

The MHRA is responsible for the designation and monitoring of UK conformity assessment bodies. Companies need to assess their product to determine if it falls within the medical device regulations. If it does, it requires a UKCA (and/or European CE mark depending on historical and future deployment) either self-certified, or via a notified body.

The UK Government webpages on regulating medical devices in the UK provides more information.

The Patient Safety Commissioner

The risks of medical devices were highlighted by the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review as part of the investigation into the vaginal mesh scandal. As a result, the Medicines and Medical Devices Act 2021 (MMDA) came into effect on 11 February 2021. The first Patient Safety Commissioner was appointed in September 2022, with the core duty of promoting patient safety in relation to the regulation of human medicines and medical devices.

Digital technology assessment criteria

Digital tools are now evaluated in the NHS by the digital technology assessment criteria (DTAC) and any developer or system supplier wanting access to the NHS markets or systems will need a DTAC evaluation. These criteria evaluate digital technologies across a range of areas including clinical safety, data protection, technical security, interoperability criteria, usability, and accessibility.

DTAC includes:

- Clinical safety | Products are assessed to ensure that baseline clinical safety measures are in place and that organisations undertake clinical risk management activities. The standards include DCB0129 (Clinical Risk Management: its Application in the Manufacture of Health IT Systems) and DCB0160 (Clinical Risk Management: its Application in the Deployment and Use of Health IT Systems).

- Data protection | Products are assessed to ensure that data protection and privacy is ‘by design’ and the rights of individuals are protected.

- Technical assurance | Products are assessed to ensure they are secure and stable.

- Interoperability | Products are assessed to ensure that data is communicated accurately and quickly whilst staying safe and secure.

- Usability and accessibility | Products are allocated a conformity rating having been benchmarked against good practice and the NHS service standard.

Digital clinical safety

Digital tool developers and larger organisations should have a clinical safety officer (CSO) who is a suitably qualified clinician with a current registration and experience in risk management and its application to clinical domains.

A full analysis of digital clinical safety can be found at the NHS Digital clinical safety strategy. It outlines the case for improved digital clinical safety across health and social care. The aim of the strategy is to improve the safety of digital technologies in health and care, now and in the future, and to identify, and promote the use of, digital technologies as solutions to patient safety challenges.

There is another article in this series covering digital clinical safety in more detail.

Cyber security

Security incidents affecting connected medical devices could cause significant disruption to the delivery of healthcare services or put patients at risk of harm.

The cyber security of connected medical devices requires special consideration due to three related issues:

- security updates, patches and potentially virus signatures must be properly assessed by the supplier and confirmed as safe before they can be implemented on the medical device – it can take three months from the time that a security update is released

- when security updates are released, they are retro analysed by attackers, increasing the likelihood that exploitable vulnerabilities will become known

- the latest security mitigations not being present increases the impact of vulnerabilities, making exploitation more likely to succeed, and making detection of any exploitation more difficult

In combination, these issues mean that high-impact security incidents become more likely to occur.

There is detailed NHS guidance on how to mitigate this risk:

There is also another article in this series about cyber security.

Commissioning services

Medical devices and digital health tools will inevitably be commissioned at all levels ranging from practice level, primary care networks, to integrated care systems and at a national level.

The DTAC should be used by healthcare organisations to assess suppliers at the point of procurement or as part of a due diligence process, to make sure new digital technologies meet a minimum baseline standard.

NHS procurement frameworks have been designed to provide NHS commissioners with a selection of digital tools that are compliant with relevant standards and meet the needs of the NHS.

The Academic health science networks can also help with the co-design, implementation and evaluation of new medical devices and digital tools.

Healthcare commissioners including primary care networks and integrated care boards should identify a medical devices safety officer (MDSO), who can regularly review information from the national reporting and learning system (NRLS) and the MHRA, to support improvements in reporting and learning and to take local action to improve the safety of medical devices.

Medical devices | implementation best practice

The following are top tips for integrating medical devices and digital tools into practice:

- You should ensure that any medical device or digital health tool you recommend is safe, effective, and regulated so that any risks are mitigated.

- Any medical device you prescribe or provide is done in keeping with national and local guidance such as that from The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) or your local formulary.

- The risks and benefits should be clearly explained to the patient.

- Medical implants including coils, intrauterine systems, hormonal implants and catheters should be documented well including patient consent, unique identifiers, the person carrying out the procedure and information should be provided to the patient.

- You must use medical devices as described by the manufacturer’s instructions. Any other use is considered ‘off-label’ use. Without approval this would be at your own risk and you, or your employer could become liable for civil claims for damages if something goes wrong.

For more information, please refer to:

Implementation of digital health tools | Lessons learned

Digital innovations are often presented as off-the-shelf solutions to problems in healthcare, but the success of digital innovations depends on the way they are implemented. Context matters, and local factors must be considered when designing new services.

Co-design with end users is essential when designing new care pathways, as is dedicating sufficient time and resources to governance, training, and evaluation.

A large-scale evaluation of digital technologies implemented across health and social care in East London (by the Nuffield Trust) resulted in the identification of 10 key lessons:

- Dedicate sufficient time and resource to engage with end users.

- Co-design or co-production with end users is an essential tool when implementing technology.

- Identify the need and its wider impact on the system, not a need for a technology.

- Explore the motivators and barriers that might influence user uptake of an innovation.

- Ignore information governance requirements at your peril.

- Don’t be afraid to tailor the innovation along the journey.

- Ensure adequate training is built in for services using the technology.

- Embedding the innovation is only half the journey – ongoing data collection and analysis is key.

- Ensure there is sufficient resource, capacity, and project management support to facilitate roll-out.

- Recognise that variation across local areas exists and adapt the implementation accordingly.

Reporting adverse incidents or near misses

It is important to record and report any adverse incidents or near misses with medical devices in the same way you would with medication. General Medical Council (GMC) guidance states:

‘Adverse incidents involving medical devices, including those caused by human error, that put, or have the potential to put, the safety of patients, healthcare professionals or others at risk must be reported to the medical device liaison officer within your organisation and the relevant national body‘.

The relevant national bodies are:

- in England and Wales, MHRA reporting adverse incidents

- in Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland Adverse Incident Centre.

- in Scotland, Health Facilities Scotland online incident reporting

You should also inform the Clinical Safety Officer (CSO) of the medical device company.

Be cautious about ‘tools and devices’ included in your clinical system. Errors should be reported in the first instance to the system supplier who should liaise with the developer to resolve any issues.

The Government website has more information on reporting incidents and problems.

Benefits of medical devices and digital tools

The many benefits of digital tools to patients include:

- improved access to care – digital tools can facilitate communication between patients and clinicians through messaging, video calls and multimedia such as images.

- empowerment to self-care at home – for example long-term conditions with monitoring medical devices and condition specific apps

- supporting families/carers – to become more involved in long-term care of a patient at home

- reduced prescribing – for example treating overactive bladder with a pelvic floor exercise app, or treating depression with a mental health app, instead of medication which can reduce costs and side-effects associated with medication and with comparable outcomes with some conditions

- new ways of identifying or treating disease – using artificial intelligence (AI) which can spot patterns of illness not previously identified, improving early diagnosis

Risks and issues of medical devices and digital tools

Risks and issues associated with the use of medical devices and digital tools include:

- lack of regulation – before apps are published on app stores, the sheer number of apps and pace of change can be bewildering for clinicians and patients

- lack of integration and failure of integration – can mean if new systems do not communicate directly with existing systems inefficiencies can build up meaning valuable time is taken up manually transferring data between disparate systems. Similarly if there has been an integration and it breaks, this can result in clinicians not having up to date information

- reliability and cybersecurity – become more critical as medical devices become connected to the internet and perform higher risks functions, e.g. insulin pumps or artificial pancreases. This creates novel risks to privacy, physical safety, or both. This can be mitigated by ensuring that software is designed in a safe way, kept up to date and patched as new vulnerabilities are identified and by observing appropriate standards such as UKCA marking and due diligence (e.g. DTAC)

- systems failure – power outages or server failures become more of a risk as care becomes more dependent on apps or electronic devices. Thought must be given to contingency or back up arrangements

- adverse incidents – are inevitable with any new technology, but they should be mitigated against by using clinical risk management (e.g. DCB0129 and DCB0160). It is essential that real-world testing and post-market surveillance occur. After adverse incidents or near misses are reported, learning should occur to improve system safety

- increased complexity of primary care – can be mitigated by carefully redesigning care pathways when implementing new medical devices and digital tools. It is important to consider how new systems will integrate with existing systems.

- digital exclusion – can occur when new technology leads to unequal access to care from patients who may lack connected devices, internet connection or IT skills. Whilst 87% (2020) of the UK population now have a smartphone, 13%, including the poorest and most vulnerable, don’t. This can be mitigated by ensuring that new services can be accessed by everyone and people from disadvantaged backgrounds are supported in accessing new digital services.

- risk of digital discrimination – where medical devices or digital tools treat a patient unfairly or inaccurately based on a certain characteristic (which could also be a protected characteristic such as race or gender). This can be mitigated if medical devices or algorithms are well designed and tested on a representative population.

Summary

- Incorporate apps into your clinical work, especially ones that are supported by high quality evidence.

- Use accredited app libraries or frameworks as a basis for finding new apps.

- Think ‘is this a medical device?’ when an app is recommended to you and look for UKCA marking.

- Use NHS procurement frameworks and the DTAC when commissioning digital services.

- Check if patient consent is required to use a medical device or digital health tool, and if so what form of consent is appropriate.

- Think ‘what are the risks, and have they been mitigated?’

- Use medical devices and digital tools as intended and prescribed by manufacturers’ instructions.

- Report any safety incidents.

- Design services so that none of your patients are excluded from benefiting from new medical devices and digital tools.

- Users and patients need to be aware of how the device may store and process patient identifiable information. Practices also need to be aware of how to reset (and remove any patient identifiable data) these devices when re-issuing mobile devices.

Related GPG content

- Health equalities and inclusion

- Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning

- Primary Care Networks (PCNs)

- Interoperability

- Information governance and data protection

- NHS.UK online resource for patients

- Cyber security

- Medication safety management

- Digital clinical safety assurance

Other helpful resources

- MHRA, Devices in medical practice (checklist)

- MHRA, Software and AI as a medical device: change programme (Sept 2021)

- MHRA, An introductory guide to the medical device regulation (MDR) and the in vitro diagnostic medical device regulation (IVDR)

- GOV.UK. Guidance on when to notify the MHRA about medical devices

- e-Learning for Healthcare, Introduction to the dm&d e-learning programme

- e-Learning for Healthcare, online learning about use of medical equipment

- GOV.UK, Product specific information for medications and medical devices

- Health Research Authority, Ethical guidance on research involving medical devices and software

- European Medicines Agency, How devices are regulated in Europe

- GOV.UK, How to comply with the regulations (for manufacturers)

- GOV.UK, Medical devices regulation and safety, detailed information

- GOV.UK, Medical devices – off-label use

- GOV.UK, Medical devices – software applications

- GOV.UK, In-house development of medical devices