Introduction

The Service model for commissioners of health and social care services (2015) provided comprehensive guidance for the commissioning of services for people with a learning disability and autistic people who display behaviour that challenges. This terminology is no longer used, and the health and social care landscape has changed since 2015 – therefore an update is required.

This guidance will update the acute learning disability and autism guidance within the Service model but will not cover all elements (such as community provision) as it will form part of a suite of guidance relating to inpatient care. It should be read in conjunction with:

- Meeting the needs of autistic adults in mental health services – Guidance for integrated care boards, health organisations and wider system partners

- Acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults (NHS England),

- Community support for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults – a resource pack to support the development of local community services for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults

- Commissioner guidance for adult mental health rehabilitation inpatient services

- Commissioning framework for mental health inpatient services.

Where more recent guidance has not been published, the Service model should continue to be used as a starting point for anyone commissioning services for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

This guidance is intended to support integrated care boards (ICBs) to commission acute mental health inpatient services for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults. It is national guidance for ICBs to follow as they commission for their populations and sets out minimum standards and expectations to consider when commissioning high quality inpatient care.

People with a learning disability and autistic people should not be admitted to a mental health hospital unless there is a suspected or identified mental health need requiring inpatient care and support. The draft mental health bill seeks to limit the grounds upon which people with a learning disability and autistic people can be detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act.

It is known that people with a learning disability and autistic people have a higher risk of premature mortality often from preventable or treatable mental health and physical health conditions. It is also known that significant contributory factors for this are due to facing additional barriers to receiving health and social care services. It is therefore essential that there are no additional barriers or delays for people with a learning disability and autistic people accessing services for an identified or suspected mental health need, including inpatient services when these are clinically necessary. People with a learning disability and autistic people should have equitable access to such services, and this guidance will support this aim.

This guidance will support delivery of the commitment outlined within the NHS Long Term Plan to focus on improving the quality of inpatient care across the NHS and independent sector, including for people with a learning disability and autistic people. When commissioning services, commissioners should be confident that these services are:

- safe

- caring

- responsive

- effective

- high quality

- close to where people live

- well-led

- integrated with community services

- focused on proactively encouraging independence, recovery and swift discharge back to the community.

This guidance sets out principles for delivering services and how to apply these principles throughout the commissioning cycle. The principles relate to adult and older adult acute inpatient mental health services as well as to acute mental health inpatient services that are specifically provided for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults. Some of the guidance regarding application differs dependant on service type.

Local systems will need to use their own intelligence/data to plan for the number of adults with a learning disability and autistic adults that may require acute mental health inpatient care. To achieve this, areas (ICB’s or NHS England regions) should have an understanding of the level of need within the or geographic area – using tools such as the local integrated care strategy and joint strategic needs assessment to model the amount and type of provision required, taking into account the ambition within the NHS Long Term Plan for no more than 30 adults per million adult population in mental health inpatient care.

Modelling for mental health inpatient service provision for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults should be undertaken in conjunction with the planning of robust integrated community services including consideration of crash pads/ crisis respite locations, market development of community providers and housing provision (aligned with care and support as needed), and provision of crisis support/ intensive support teams.

This type of place based, localised commissioning aligns with the approach set out in the Health and Care Act (2022), echoes findings from the Good learning disability and autism commissioning practice and impact rapid literature review and is reflected within NHS England’s bitesize guide for local systems.

Purpose of this guidance

This guidance sets out an approach so that where an acute mental health inpatient admission may be required for an adult with a learning disability or an autistic adult:

- services have been co-designed by people with lived experience and their families

- care, treatment and support plans are co-produced with people and their families, with appropriate advocacy support

- any admission is appropriately supported by relevant specialists, for a specific indication for a mental health assessment and/or intervention that can only be delivered in an inpatient setting

- any admission is for the minimum time possible, and with timely discharge enabled through effective multi-agency working

- reasonably adjusted, personalised care, support (including advocacy), assessment and intervention is provided

- the admission is, wherever possible, to a general adult/ older adult acute mental health inpatient service and, where this is not possible due to the needs of the person, to an acute mental health inpatient service specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

Scope

This guidance relates to adults with a learning disability and autistic adults who have been assessed as requiring an acute mental health inpatient admission, due to a severe mental health need. This includes those detained in line with the Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended in 2007) in England and Wales This document should be read in conjunction with the NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults guidance.

We have included both adults with a learning disability and autistic adults. This is because adjustments, either to adult/ older adult provision, or through acute mental health inpatient services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults, should be based on the principle of personalisation and the person’s needs. Adjustments will differ for each person, irrespective of diagnosis.

The acute mental health services described that are specifically for adults who have a learning disability and autistic adults, do not distinguish between adult (between 18 and 65 years of age) and older adult services (over 65 years of age). Access to these services will be dependent on Care Quality Commission registration, and integrated care boards and providers should be mindful that there may be further training and environmental requirements for older adults using these services.

This guidance does not include the following services:

- psychiatric intensive care units

- mental health rehabilitation inpatient services

- adult secure mental health services (low, medium and high)

- Specialised inpatient services (including all-age eating disorders, perinatal mental health, mental health services for deaf people, obsessive compulsive and body dysmorphic disorders and tier 4 personality disorders).

Audience for this guidance

Although this is primarily intended for people in commissioning roles, it may also be helpful to people working in a provider setting, people with lived experience and their families, carers and representatives. We intend for this guidance to be used by anyone involved in developing and delivering acute mental health inpatient services for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

Types of acute mental health inpatient care

Acute mental health inpatient beds

These are accessed when people require assessments, interventions or treatment that can only be provided in a hospital setting (Davidson, 2021). For people admitted to an acute mental health service, a therapeutic environment provides the best opportunity for recovery. It is important that care is purposeful, personalised and recovery focused from the outset, so that people have a good experience of care and do not spend more time in hospital than necessary (NHS England). There are often separate services for adults and older adults, though there should be strong alignment between the two. Services should be delivered in line with NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults guidance.

Inpatient services which specifically support people who have a learning disability and autistic people

These were described in the model service specification as being for adults with a learning disability and/or autism who present an immediate risk to those around them and/or to themselves, and whose behaviour and/or mental state is such that assessment and/or treatment cannot be provided safely and effectively in the community, and where reasonably adjusted mainstream inpatient services would be an inappropriate environment. Sometimes these have previously been called assessment and treatment units, or ATU’s. The language of ATU’s and relating to behaviours has changed, as has the health and social care landscape.

This guidance will replace the inpatient aspect (principle 9) of the service specification. It will describe adjustments to acute inpatient mental health services, and acute mental health inpatient services specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people. The latter will replace use of ATU’s.

Differentiating between acute mental health inpatient service types for people who have a learning disability and autistic people

There are two types of provision described in this guidance:

- Mainstream acute mental health inpatient services – in the context of this document the word ‘mainstream’ refers to any acute mental health inpatient services that is commissioned for all the general population. This includes autistic people, people with a learning disability and other people for whom services have a legal duty to ensure that reasonable adjustments are made.

- Adult acute mental health inpatient services specifically for people who have a learning disability and for autistic people. Some people refer to this as a ‘specialist’ service, or an ‘enhanced’ service but it simply means that the acute mental health inpatient service, and its team, has been designed especially with the needs of these groups of people in mind to ensure they receive high quality care for short periods of time where adult or older adult services cannot be reasonably adjusted sufficiently. People who are admitted to these hospitals are still being assessed and treated within the requirements of the Mental Health Act (whether admitted formally or informally)

What is the difference?

An admission to an acute mental health inpatient setting which is specifically for autistic adults and adults with a learning disability should only take place when:

- the person has a learning disability or is autistic, and

- they meet the criteria for admission to an acute mental health hospital, and

- sufficient reasonable adjustments cannot practicably be made to the physical environment, staffing, or general approach within adult and older adult acute mental health inpatient services to provide equitable outcomes (and this is evidenced).

Key principles

Admissions to acute mental health inpatient mental health services should align with NHS England’s guidance for acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults which includes key actions which need to take place for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

Any service specifications developed, and thus services delivered, should be based on the following principles which are derived from the acute mental health guidance, co-production with clinicians and people with lived experience, and current policy.

During a mental health hospital stay care is personalised and addresses inequality

At present, there are significant health inequalities experienced by people in terms of their access to, experience of, and outcomes from acute inpatient mental health services and it is vital that action is taken at all levels to protect and advance health equality. NHS England has set out its plan to deliver more equitable access, experience and outcomes in mental health services in its Advancing mental health equalities strategy to support adherence to the Equality Act (2010).

Care should be personalised to people’s individual needs, and mental health professionals (including learning disability team members and social workers) should work in partnership with people to provide choices about their care and treatment, to reach shared decisions, and to have choice and control over the support they receive to enable independent living upon discharge. Care should take into account the person’s diverse cultural and spiritual needs, recognising that people’s identities and experiences are multifaceted, and that being a member of multiple groups that experience inequalities may compound poorer experiences of care. Co-production approaches should be used to understand and address health inequalities experienced by people with a learning disability and autistic people from ethnic minority backgrounds in line with the Race and health observatory report about the health inequalities experienced by people with a learning disability from minority ethnic communities.

Services should actively identify and address inequalities that exist within their local inpatient pathway, alongside people representing affected groups and communities. This must include ensuring that people are not prevented from accessing or receiving good quality acute mental health inpatient care simply because of a disability, diagnostic label, or another protected characteristic. Additional suggestions to improve the care offered to people from racialised and ethnic minority communities can be found in NHS England’s acute mental health guidance.

Robust community services will avoid preventable admissions

People with a learning disability and autistic people should be admitted to inpatient care on the same basis as other people. People’s needs should be evaluated on an individual basis and decision making as to the most suitable hospital inpatient setting should be clearly evidenced and undertaken in a co-productive manner with families and the person themselves.

Admission to mental health acute inpatient care should be to allow for the assessment, intervention and treatment of a serious mental health problem that requires support that can only be safely provided in an inpatient setting. Other community options such as intensive support teams or community home treatment teams should have been exhausted. Admission should be at the time it is needed, to the most suitable bed for the person’s needs, and when there is a clearly stated purpose for the admission.

This is especially true for people with a learning disability and autistic people, whether they are accessing acute adult or older adult services, or services specifically for those with a learning disability, or who are autistic.

Local protocols should be in place, and communicated across the integrated care system (ICS), so that everyone has a clear understanding of the acute mental health pathway, and when an inpatient admission may be needed. These protocols should consider the needs of adults with a learning disability and autistic adults – including consideration of how to evaluate when adult or older adult acute mental health inpatient services would or would not be able to sufficiently meet the needs of the local population.

To help support autistic people and people with a learning disability to live safe and fulfilling lives in the community, community resources should be made available to enrich the care provided by families, carers and paid support staff (if needed by the person). This should include, but not be limited to:

- training for families/carers

- support and respite for families/carers

- alternative short-term accommodation for people to use briefly in a time of crisis

- paid care and support staff trained and experienced in supporting people with a learning disability and autistic people, who may also have a mental health condition

- a choice about where and with whom they live – with a choice of housing including small-scale supported living, and the offer of settled accommodation, in line with Building the right home, 2016

- specialist health and social care support in the community – via integrated specialist multidisciplinary health and social care teams, with that support available on an intensive 24/7 basis when necessary (NHS England, 2015)

- adult mental health services that are able to meet the needs of autistic people and people with a learning disability – this should include NHS talking therapies for anxiety and depression, community mental health services and adult crisis services.

People with a learning disability and autistic people should be able to access high-quality assessment and treatment in a mental health hospital setting, and stay no longer than they need to, with pre-admission checks, and ongoing reviews, in line with the Dynamic support register and Care (Education) and Treatment Review policy and guide. This will help to ensure mental health hospital care is the right solution and discharge planning starts from the point of admission or before.

Care planning should be integrated with community services

Care should be joined up across the health, education, care, and housing system with inpatient services working in a cohesive way with partner organisations, both during a person’s inpatient stay and after discharge, so that people are supported to stay well and can further their recovery when they leave hospital. There should be a clear link between community and inpatient services.

Before admission to hospital, people may have assessments through teams in the community (whether mental health, learning disability or autism teams) – including crisis teams and intensive support teams where applicable. This will help to ensure their needs are understood, and they have clear and measurable objectives set for their admission to hospital and receive care in an appropriate environment.

One of the key adjustments that can be supported is for community health teams, social care teams and community support providers to form part of the multidisciplinary team that supports someone during their inpatient stay. They can then support the person throughout their admission and after discharge, which enhances continuity of care. It can also enable the sharing of knowledge and transfer of skills between the inpatient mental health and community team.

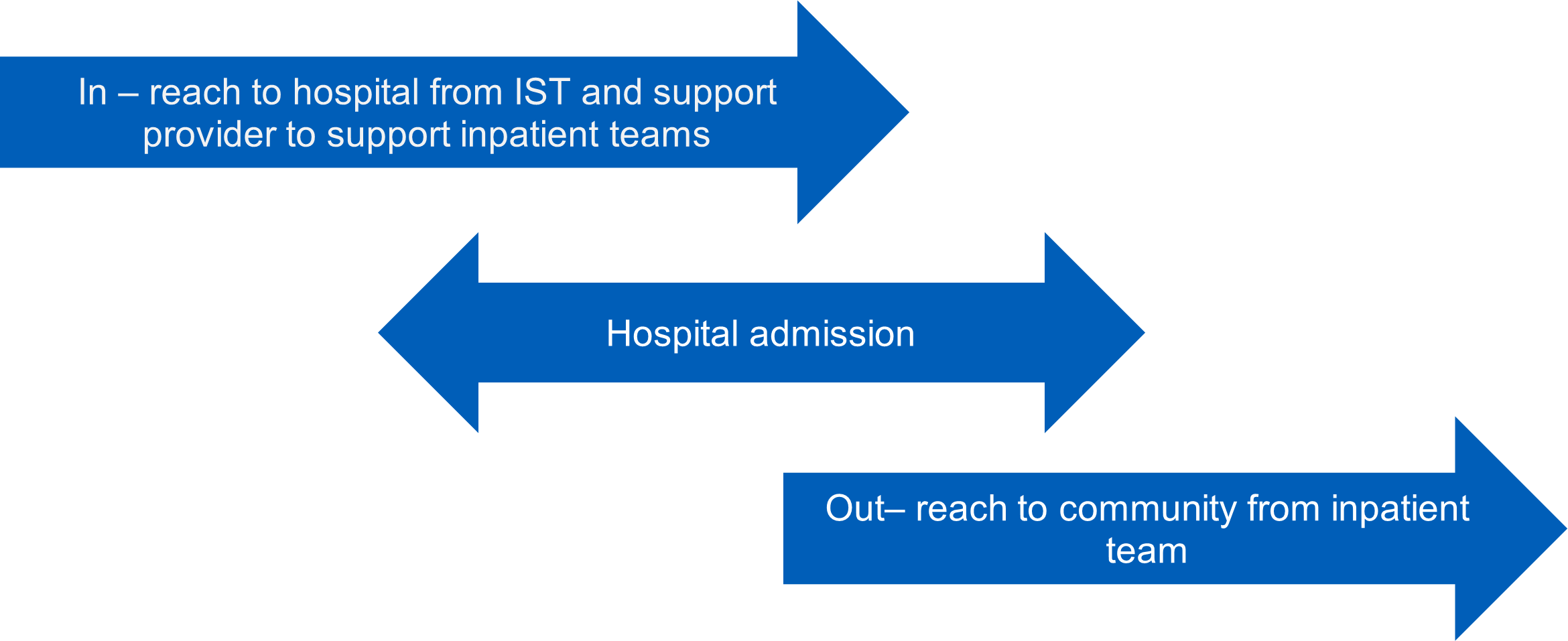

Example model of how care planning should be integrated with community services

This diagram shows three arrows which overlap with each other. The top arrow shows community services working into hospitals, which could include intensive support teams and community support providers. This will ensure consistency and robust transitions. The middle arrow shows the hospital admission. The bottom arrow shows the inpatient team working into the community to support the transition from inpatient services, to ensure consistency and robust transitions.

Providing in-reach support at the point of admission, and support beyond discharge, provides continuity and can help to develop wrap around support plans building on the knowledge and skills of families, carers and health and social care professionals. This in turn provides consistency and enables better integration into community services and reduced re-admission rates. Where a person will be in receipt of health and/or social care community support, providers of these services should be able to work in the inpatient setting to support an effective transition to community placements.

Provide care in general adult and older adult acute mental health inpatient services with reasonable adjustments, where possible

Many adults with a learning disability and autistic adults may be supported with reasonable adjustments to adult or older adult acute mental health inpatient services. Adjustments should be identified through good personalised care and support planning conversations which highlight what matters to the person and what good support looks like for them. The person may already have a personalised care and support plan which can be reviewed and amended to include information about reasonable adjustments.

Admission to adult/older adult acute mental health inpatient units for autistic people and for people with a learning disability should be due to a suspected/diagnosed mental health condition. Having a learning disability or being autistic should not be reasons for an admission, but reasonable adjustments should be made for these and any other protected characteristic. Where reasonable adjustments are required, these should be detailed in the patient record using the reasonable adjustment flag function.

A holistic assessment should take place on admission. This should form part of the person’s care planning. The team should check key information from the person’s electronic patient record with them and their chosen carer(s) – noting any changes/updates. This is to ensure that the objectives and personalised care and support plan is meeting the person’s needs. The assessment will include identifying any recorded advance choices and reasonable adjustments required, and may include undertaking or updating assessments for autism, sensory needs, mental health, physical health, trauma, and learning disability. Assessments of this nature should not be the sole reason for admission and where possible should be undertaken in the community.

Staff should have had training, accessed tools and resources, and developed experience and expertise on reasonable adjustments within their mental health acute ward setting. Where relevant they should have access to specialist advice from a learning disability team, or autism team, where there are specific issues about interactions with these diagnoses that are outside the usual expertise for that team and are needed for that person.

Any reasonable adjustments needed should be made – whether to the physical environment, therapeutic offer, staffing complement or other. On the rare occasion that these adjustments cannot be made, and care and treatment cannot be provided in the way the person needs, or there are significant safeguarding risks which cannot be mitigated, then it may be appropriate for the person to access an acute mental health inpatient setting specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

Admission should be therapeutic

People should receive timely access to the assessments, interventions, and treatments that they need, so that their time in hospital delivers therapeutic benefit. Care should be delivered in a therapeutic environment and in a way that is trauma-informed.

People with a learning disability and autistic people should not be admitted to a mental health hospital unless there is a suspected or identified mental health need requiring inpatient care and support. The draft Mental Health Bill prevents people from being admitted for treatment on the basis of autism or learning disability.

An inpatient stay should be timely and should be in a service as close to home as possible

When a person requires care and treatment that can only be provided in an acute mental health inpatient setting, they receive prompt access to hospital provision which supports their needs and is close to home, so that they can maintain their support networks and community links (Department of Health and Social Care, 2022).

An inpatient stay should be for the minimum time possible, for assessment and/or treatment which can only be provided in hospital

In 2017 the Senate guidance was published on length of stay for adults with a learning disability. In 2023, in light of the Mental health implementation plan and NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults the guiding principle should be that an inpatient stay should be for the minimum time possible, for assessment and/or treatment which can only be provided in hospital. To achieve this the NHS England Mental Health Programme has developed two metrics for acute mental health inpatient services to monitor their performance against, this includes long lengths of stay of over 60 or 90 days for adults or older adults respectively.

Discharge planning should be robust

People should be discharged or transferred to a less restrictive setting as soon as their purpose of admission is met, and they no longer require care and treatment that can only be provided in a mental health hospital – that is, that they are clinically ready for discharge. For this to happen, there needs to be an estimated date of discharge set and robust discharge planning, ideally from before an admission, but at a minimum from the very start of a person’s admission. Discharge planning should include the person and their family/carers and focus on developing personalised care and support plans (including housing) with outcomes clearly identified by the person and their family/carers. Planning will involve people from all relevant services, who will be involved in providing housing and support in the community. There also needs to be a range of community support available, which meet different levels of needs and enable people to maintain their wellbeing and live as independently as possible after discharge. This might include, for example, the option of having a personal health budget (PHB), noting the right of people eligible for section 117 aftercare to have a PHB.

Key professionals should be named and accountable to facilitate discharge. Where further funded care is required there will be a named budget holder for the person’s care. Where a new funded support or housing arrangement is required to enable discharge, the named budget holder from the integrated care system (ICS) is responsible for commissioning the identified requirements within an agreed timeframe. There will be a named person acting as care coordinator, keyworker, or system navigator for people with complex needs and their families (NHS England, 2023).

Service models will be co-produced

Service models should be co-produced with people who have a learning disability and autistic people, who have experience of inpatient mental health services, and their families and carers.

What the team delivering acute mental health care to adults with a learning disability and autistic adults should be like

All services should work in line with the principles outlined above. The next section of this guidance describes what acute mental health inpatient services should deliver to meet the needs of adults with a learning disability and autistic adults. Some items will be relevant to all acute mental health inpatient services, whilst some will be relevant only to acute mental health inpatient services specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people. Each section will stipulate which services it relates to.

One of the most important things we heard from people as we developed this guidance was the importance of a team who are knowledgeable and skilled both in supporting people with a learning disability and autistic adults and supporting people with a mental health condition.

People were clear that the majority of staff competencies should be present whether the person is supported in a mainstream acute setting, or an acute mental health setting specifically for people with a learning disability and autistic people. This was also true of many of the professional disciplines available to the person within the hospital multidisciplinary team. An example is that a service specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults may require greater occupational therapy input as a higher proportion of people are likely to have sensory needs (Doherty et al, 2023).

Both types of service should employ people with a learning disability, and autistic people, and their family members as experts by experiences for specific roles such as peer support or quality checking, and for training/recruiting staff.

How many people should be in the team

Staffing levels have a critical impact on people’s experience of inpatient care, for example, affecting the activities and interventions that are on offer and whether people can leave the hospital grounds. It is therefore crucial that inpatient services have sufficient staffing levels and there is not an over-reliance on temporary staff, which impacts on people’s ability to build up a relationship with the inpatient staffing team. Recommended full-time equivalents (FTEs) for different staffing groups are not included in this guidance, because determining the right staffing model for a given population involves assessing a range of local factors and no single model will be applicable to all areas. However, in line with the fundamental safer staffing principles set out in the National Quality Board’s guidance, and Developing workforce safeguards guidance, all staffing establishments should be reviewed biannually using a triangulated approach, utilising evidence-based workforce planning tools, professional judgement of the clinical team, review of quality and safety outcomes, and benchmarking with peers. The validated, evidence-based workforce planning tool for inpatient mental health services is the Mental health optimal staffing tool. The tool is free for NHS trusts in England to use and can be licensed via https://www.innovahealthtec.com. Further resources from NHS England on safe staffing in mental health services can be accessed on the NHS England website.

We have heard, through our engagement sessions, that for adults with a learning disability, and autistic adults, continuity of care is critical for recovery. Mental health providers should consider this in their delivery of acute mental health inpatient services and, wherever possible, keep to a minimum the number of team members a person is supported by, in line with the Royal College of Psychiatry guidance.

Who should be in the team

Commissioners should ensure that the service commissioned has a broad range of disciplines engaged in service delivery. Integrated care boards (ICBs) should consider their available workforce and service specifications should confirm the expectation that providers work towards the following disciplines being included in service delivery, derived from guidelines from the Royal College of Psychiatry for both mental health and learning disability services, feedback from stakeholders, and NHS England:

- experts by experience/ peer workers

- registered mental health nurses – including advanced nursing practitioners

- multiprofessional advance practitioners

- multiprofessional non-medical consultants

- creative or art therapists

- clinical pharmacists

- occupational therapists (OT)

- speech and language therapists (SALT)

- clinical psychologists

- psychiatrists

- social workers

- autism peer support workers

- health care assistants

- learning disability nurses

- physiotherapy

- a role (or more than one role) which clearly links to social care and housing.

For general adult/older adult acute mental health inpatient provision commissioners may specify provision of the above disciplines through ‘in-reach’ however, for services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults, they should form part of the core staffing complement.

Although the above roles should feature in both service types, we would expect a different staffing ratio between the two service types. In services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults, they should have an multidisciplinary team which has significant experience in supporting these groups of people and a higher complement of, for example, learning disability nurses, SALTs and OTs.

The person should always be at the centre of the team, and families and advocates should be considered in the team approach. It may be beneficial to nominate a champion within the staff team of an acute mental health inpatient setting to champion the needs of autistic adults and adults with a learning disability. The purpose of this role would be to raise awareness of people’s needs relating to their diagnosis, including reasonable adjustments and self-advocacy.

Skills, competencies and knowledge

There are a range of skills, knowledge and competencies that will enable a mental health acute inpatient team to meet both a person’s mental health needs and needs relating to their learning disability or autism. These will be applicable regardless of the acute mental health inpatient type.

People in a commissioning role should ensure that services have access to the specialist knowledge and skills to meet the unique needs of people with a learning disability and autistic people who access and use their services, as well as those who support them.

Services should grow and develop the acute inpatient mental health workforce in line with national workforce profiles, so that inpatient services can offer a full range of multidisciplinary interventions and treatment. Staff wellbeing, training and development should be supported, so that inpatient services are an attractive place to work, and staff are enabled to offer compassionate, high-quality care.

The Health and Care Act (2022) sets out the requirement that all health and social care providers registered with the Care Quality Commission must ensure that their staff received training on learning disability and autism appropriate to their role. Staff must be trained and then routinely receive refresher training in how to deliver care to people with a learning disability and autistic people in a way that takes account of their rights, unique needs, and health vulnerabilities, and ensures that adjustments to how services are delivered are tailored to each person’s individual needs (NHS Improvement, 2019). Induction training should take place for all staff which includes shadowing of more experienced colleagues, and a competency-based assessment post induction which incorporates training on communication.

Staff members will have knowledge, skills and experience, at practitioner and at expert level, of effective working with people with a learning disability, and autistic people, in accordance with relevant National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance, and be able to demonstrate competencies in line with the core capabilities frameworks. They will also be skilled and experienced at providing support and treatment for people with serious mental health problems.

Services should access the training offer provided by NHS England which is designed to equip our multidisciplinary workforce with the right values, skills and capabilities to care and support people in order to create a shift in leadership capability and capacity in addition to positive changes to culture. This includes, but is not limited to:

- Oliver McGowan mandatory training

- autism advanced practitioners and non-medical consultants

- autism peer support workers

- national autism trainer programme for mental health staff

- chief nursing officer learning disability nurse CPD award

- autism training for psychiatrists (general) and training for psychiatrists in or moving to acute mental health inpatient services specifically for autistic adults (and adults with a learning disability)

- Care (Education) Treatment Reviews training.

This guidance does not aim to offer a comprehensive list of skills and competencies for staff working in acute inpatient mental health settings, as these will vary across professional groups and depend on seniority. There are however various skills and competencies in areas highlighted in this guidance, including cultural competency, that all staff should demonstrate in their daily practice. A compilation of these skills and competencies can be found in Appendix 6.

The physical environment

The Care Quality Commission’s 2020 report, Out of sight – who cares? reviewed the use of restrictive practice in hospitals and concluded that many ward environments are chaotic and non-therapeutic, often triggering behaviours that necessitated the use of segregation and restraint. It highlights that inpatient mental health wards can be particularly distressing environments for some people and there are often environmental problems such as noise, echoes and harsh lighting which can limit the therapeutic experience. It is therefore vitally important that these environmental factors are considered specifically in relation to adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

Adjustments to support admission to general adult/older adult acute mental health inpatient services

When a person requires an admission to an acute mental health hospital, the physical environment should feel safe and inviting. This helps people to feel cared for and supported while in hospital and is supportive of recovery. Inpatient wards should strive to provide environments that meet the needs of all people who are admitted, including attention to the following guidance and reasonable adjustments.

Services should be designed and delivered in line with the Department of Health’s Health building note 03-01: adult acute mental health units (2013) and align with environmental considerations within NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults.

Consideration should be given to the sensory needs of autistic adults (who may also have a learning disability) and the SPACE framework should be considered, which provides examples of adjustments. Work undertaken by the Mental Health team at NHS England: the Star Wards project, and the work of the National Development team for inclusion, who developed ten principles for ‘sensory friendly wards’, and the Autism team at NHS England who developed this sensory friendly resource pack have contributed to 4 key areas which should be considered to ensure that ward environments are as conducive as possible to supporting recovery. Although work originally developed regarding sensory friendly wards was specific to the needs of autistic people, it has been recognised that it has the potential to improve the experience of people in inpatient settings, regardless of whether they have sensory differences or not. Therefore, all mental health hospital settings should include the following:

- Involvement: ensuring current inpatients, and those with recent experience review all areas of the ward environment, and on an individual basis ensure that the person has, where safe to do so, an environment and possessions which make them feel as comfortable as possible. This will include ensuring that information in a format which is accessible to them – for example easy read, plain English or pictorial information depending on the needs and preferences of the individual person.

- Meeting sensory and cognitive needs: ensuring lighting is sensory friendly, noise is reduced, and smells are neutralised. Signage should also be clear, considering the need for contrasting colours, clear typeface and incorporating visual cues or symbols to aid comprehension.

- Attractive and engaging shared spaces: ensuring décor (where the person chooses) is homely and includes items such as artwork, cushions, indoor plants, painted walls (for longer term admissions). Access should also be provided to a low stimulus environment where appropriate for the person – either scheduled or on request, and outdoor spaces, as well as a variety of other areas (for example, gym)

- Ensuring privacy, dignity and safety: ensuring each person has access to their own bedroom and, wherever possible, their own ensuite bathroom. Making sure that minimal restrictive interventions, maximum safety (for example, reducing ligature risks) and providing suitable facilities for people of each gender and people who are transgender or non-binary. Please see NHS England’s guidance on same- sex accommodation. Updated guidance on improving privacy, dignity, and safety (which will cover same-sex accommodation) is currently in development.

The Green light toolkit can support in the self-evaluation of mental health services for adults with a learning disability, autistic adults, and autistic adults who have a learning disability.

For adults with a learning disability and autistic adults in an adult or older adult acute mental health inpatient setting, providers and commissioners should also be able to evidence consideration of:

- Involving adults with a learning disability and autistic adults in the design and review of environments in a way that is meaningful to them, including using a range of communication methods. This may include providing longer time frames for people to consider the options and respond. Where the person would be unable to communicate their wishes, family views should be considered,

- Use of communication aids in line with the person’s preferences and use of clear language with minimal jargon, larger text, use of symbols or pictures, or Makaton.

- Whether autistic adults and adults with a learning disability need to be prioritised for an ensuite, depending on their needs, where ensuites are not available for everyone on the ward.

Acute mental health inpatient services specifically for adults with a learning disability, autistic adults, and autistic adults who have a learning disability

As with acute adult/older adult mental health inpatient provision, there should be a clear purpose of admission and the primary aim of these services will be to provide assessments, interventions and treatment for serious mental illness which can only be provided in hospital.

There may be occasions where sufficient environmental adjustments cannot practicably be made to adult or older adult general acute mental health inpatient services. Where equitable therapeutic outcomes are not achievable through reasonable adjustments within adult and older adult acute mental health settings for a person, it may be necessary for integrated care boards (ICBs) to consider commissioning acute mental health inpatient services specifically for these groups of people.

Ideally these services will be co-located with an acute adult or older adult acute mental health inpatient service. This is to provide the opportunity for a shared workforce and to enhance skills transfer across teams – both from mental health teams to learning disability or autism specific teams, and vice versa. This is important as people have told us that often staff do not have knowledge across both learning disability or autism, and serious mental illness, for example how one diagnosis interacts with another.

We recognise that co-location may not always be possible as each ICB will have its own existing estate, and estate development plans which should be taken into consideration. Where this is not possible there should be plans in place to support close co-working so people are not disadvantaged by estate constraints.

Regardless of whether co-location is possible, the services should aim to offer the following additional provision in relation to the physical environment:

- Access to communal areas to enable socialising with others should the person choose to do so.

- Sensory friendly environments which are individually adjustable – for example individually controlled temperature to suit the person’s needs.

- Environments that meet the needs of the person to facilitate recovery – such as considering the ability to accommodate a pet (either long term, or to visit), welcoming areas for family, carers, and friends to visit regularly, individual storage areas where the person can access their items but are not overwhelmed by them visually.

- Lighting throughout the services which aligns with current best practice – particularly considering hum and flicker.

- Consideration of lights/torches when undertaking general ward checks/ observations at night, and whether this may impact people with a learning disability or autistic people.

- Access to an outside space per person – directly accessed from the person’s individual living space or bedroom, to enable an alternative route, when going via a larger ward it may lead to sensory overload or difficulty.

- Access to a sensory room.

- Silent alarms to reduce noise.

- Door softeners to reduce noise.

- Windows which open to reduce the noise of ‘forced air’, and where this is not possible, signage to this effect to give people advance warning before they enter this area.

- Access to vehicles to access therapeutic services and activities within the community provision, where the person is unable to access this by other means.

- Where possible, foldable doors to increase space and facilitate distance when needed.

- Sound absorbent panels to reduce echo.

- Tools to reduce the sound of keys, either via digital options or, for example, by separating the keys out.

- Consideration of where food is prepared to minimise any impact this may have on people.

Where new buildings are developed, or repurposing is being undertaken, sensory needs and the needs of people with a learning disability and autistic people should be considered, including adherence to Design for the mind – neurodiversity and the built environment guide.

People in a commissioning role and providers should ensure that anyone being cared for in a single person environment is still able to access communal areas, that enable interaction with others. This is particularly key to ensure that the thresholds of long-term segregation or seclusion, as defined by the Mental Health Act Code of Practice, are not met unintentionally.

Baroness Hollins’ recent report includes definitions of solitary confinement. The report states that “Solitary confinement also refers to practices where people are detained in individual bespoke flats and/or housing and where there is enforced denial of meaningful human contact with peers. It does not constitute solitary confinement if a person is living alone and meaningful human contact is unrestricted, for example the person is free to engage face to face with friends, family and peers, and so on, at their will”.

People in individual settings should not be prevented from having contact with anyone outside the area in which they are confined (if under long-term enhanced observation) as this will amount to either seclusion or long-term segregation as defined by paragraphs 26.103 – 26.160 of the Mental Health Act Code of Practice. Family members and advocates must have unrestricted access to people in these settings – interaction should not be limited to staff and peers.

In contrast to long-term segregation and seclusion, single person environments in mental health hospitals should not prevent a person from mixing freely with other patients on the ward or unit and neither should they be prevented from leaving. Where a single person environment is in use there should be sole use of a bedroom, lounge/living area, and bathroom.

Therapeutic interventions for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults

Adults with a learning disability and autistic adults should have equitable access to adult/older adult acute mental health inpatient services. When accessing these services there may be adjustments required to the therapeutic interventions for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults.

These adjustments where required should start at the point of admission. The formulation review that takes place within seventy-two hours of admission should also include consideration of how interventions need to be reasonably adjusted for the person (NHS England, 2023). The view of the person, their family, independent advocate, and professionals within community services who know the person should also be considered when contemplating adjustments to service provision. The local intensive support team and community teams should be used to provide a ‘consultative role’ for adult and older adult acute mental health services and offer guidance relating to person specific reasonable adjustments.

Once a person has been admitted to hospital, they should receive care that delivers therapeutic benefit throughout their inpatient stay. Inpatient services should support the provision of a therapeutic environment to enable delivery of trauma informed and personalised care (in line with existing evidence-based models). They will also provide a programme of age-appropriate activities and interventions that have been co-produced with people currently on the ward which run daily, including at weekends and in the evenings. For people who have an education health and care plan, outcomes within this should be supported wherever possible.

Adjustments to support admission to general adult/ older adult acute mental health inpatient services

All interventions should adhere to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on specific mental health problems. This applies to general adult/ older adult acute mental health inpatient settings, and acute mental health settings specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults. Interventions should be adapted to consider the needs of the person with a learning disability or autistic person. NICE guidelines indicate that this should include:

- tailoring psychological interventions to the person’s preferences, level of understanding, and strengths and needs – for example increased time with clinicians undertaking therapeutic interventions

- considering any physical, neurological or cognitive impairments or differences

- consideration of any sensory needs including consideration of a sensory assessment and adjustment of the environment to alleviate difficulties

- ensuring interactions and interventions are adapted to meet the person’s communication needs – for example use of social stories to support the person to understand why they are in hospital and what will happen during their stay, and development of communication passport. This should include communication adjustments in therapy, appointments to support the person with their expressive and receptive communication

- considering the person’s need for privacy

- collaboration with the person, their family, carers, or support staff

- develop an understanding of how the person expresses or describes emotions or distressing experiences

- agree the structure, frequency, duration, and content of the intervention, including its timing, mode of delivery and pace – particularly being aware that people might need more structured support to practise and apply new skills

- assess whether support from community and learning disability nurses is needed for physical investigations (such as blood tests)

- consideration of the potential impact of pharmacological interventions on other medication and/or health conditions, and adherence to STOMP guidelines.

For autistic adults the additional considerations below should be included in services commissioned, in line with NICE guidance:

- increased propensity for elevated anxiety about decision-making in autistic people

- greater risk of altered sensitivity and unpredictable responses to medication, including adverse effects and physical health problems

- sensitivities and how these might impact on the delivery of the intervention

- importance of predictability, clarity, structure and routine for some autistic people – including advanced notice of events such as ward rounds, C(E)TRs, leave, visits and timetabling/ scheduling/planning, which is adhered to

- adapted meal plans to accommodate sensory preferences and aversions.

Specific interventions to support adults with a learning disability in acute mental health services specifically for autistic adults and adults who have a learning disability

In addition to the adjustments noted above there are specific interventions which could be considered to support adults with a learning disability. Acute mental health services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults should have the skills within the team to deliver these interventions, as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance:

- cognitive behavioural therapy, adapted for people with a learning disability to treat depression or subthreshold depressive symptoms in people with milder learning disabilities

- relaxation therapy to reduce anxiety in people with a learning disability

- graded exposure techniques to treat anxiety symptoms or phobias in people with a learning disability

- access to specialists with expertise in treating mental health problems in people with a learning disability to start medication to treat a mental health problem in adults with a more severe learning disability.

Services should also implement the five good communication standards to provide reasonable adjustments to communication.

For adults with a learning disability, commissioners may wish to consider advising use of the baseline tool for services to identify which recommendations are relevant for the adult being supported, how these can be implemented, and progress against these.

Specific interventions to support autistic adults in acute mental health services specifically for autistic adults and adults who have a learning disability

In addition to the adjustments noted above there are specific interventions that could be considered for autistic adults. Acute mental health services specifically for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults should have the skills within the team to ensure these are considered, as per National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance:

- awareness of the potential for greater sensitivity to side effects to medication and idiosyncratic responses in autistic people

- for those who have difficulties with social interaction, access to a group-based social learning programme focused on improving social interaction (or an individually delivered programme for people who find group-based activities difficult)

- access to advice and support from staff specifically trained to deliver and adapt interventions to autistic people

- implementation of the five good communication standards to provide reasonable adjustments to communication

- adaptations to the method of delivery of cognitive and behavioural interventions for autistic adults and coexisting common mental disorders such as:

- a more concrete and structured approach with a greater use of written and visual information

- placing greater emphasis on changing behaviour, rather than cognitions, and using the behaviour as the starting point for intervention

- making rules explicit and explaining their context

- using plain English and avoiding excessive use of metaphor, ambiguity and hypothetical situations

- involving a family member, partner, carer, advocate or other professional (if the autistic person agrees) to support the implementation of an intervention maintaining the person’s attention by offering regular breaks and incorporating their special interests into therapy if possible (such as using computers to present information)” (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012).

Discharge

Discharge planning should ideally begin prior to, or at a minimum, at the point of admission, and consider the purpose of admission, intended outcomes of the admission, and ensure it considers the person’s needs after hospital are planned for. These should include needs related to health, social care, education, occupation, and housing. Strong links should be made with relevant community services (including housing) prior to, and during the admission. For each person it should be clear where they are on the 12-point discharge plan, as outlined in the Care (Education) and Treatment Review and dynamic support register policy. More information pertaining to housing as a support to discharging people from hospital can be found in NHS England’s Brick by brick: resources to support mental health hospital to home discharge planning for autistic people, and people with a learning disability (2023).

Each person should have a discharge plan in place that includes:

- an estimated date of discharge

- proposed discharge location

- any continuing treatment, support or aftercare which will be provided and by whom, including requirements if a person has an education health and care plan

- details of when, where and who will follow up with the patient post discharge (carried out within 72 hours of the person’s discharge),

- a housing needs specification (if a new home or accommodation solution will be needed, or if adaptations will be needed to the person’s existing home)

- any actions needed (and accountability for those actions) to secure the required housing in a timely way, to support discharge. This could include actions to maintain the person’s existing home (liaising with the Housing Benefit team, if relevant, and ensuring rent or mortgage payments are covered while the person is in hospital), making any adaptations to the property as needed, or identifying a new home for the person (whether sourced via a specialist or supported housing provider, securing a social or private rented tenancy, purchasing a property on the open market, or developing new build housing)

- inclusion of pre-admission presentation ‘baseline’

- protocols for transfer or shared care between learning disability and generic mental health services

- details of key parties (for example, family, carer, advocate, provider, local health services)

- transferrable personalised assessment, care, support and housing plans with clear outcomes identified by the person

- crisis and contingency arrangements including details of who to contact

- a thorough assessment of the person’s social, safety and practical needs to reduce the risk of suicide on discharge

- an occupational assessment of the person’s home environment, as applicable

- a health action plan as applicable

- medication plans, including monitoring arrangements

- as relevant, capacity assessments, when the person has discharged themselves against medical guidance (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015; Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2017).

People should be supported to leave hospital when they are clinically ready for discharge. To ensure people do not spend avoidable time in hospital when they are clinically ready for discharge, robust discharge processes should be put in place that help identify what the blockers to discharge are and how to resolve them – this includes holding multi-agency discharge events. These processes should not exclude adults with a learning disability or autistic adults.

At the point of discharge, the above plan should be forwarded to the person’s registered GP and other relevant parties (as information sharing agreements and consent allows).

A personalised care and support plan (PCSP), which includes consideration of housing and sensory needs, that can transfer with the person into the community should be prepared and available to support discharge. The person may have been admitted with an existing PCSP, which should be reviewed and amended to reflect any relevant changes.

The person must be actively involved in discharge planning, in a way which is meaningful and beneficial to them. Consideration should be given as to whether the person should be, with their consent, on the local dynamic support register.

Where community support will be provided there should be the opportunity for team members to work alongside hospital staff to get to know the person, and their needs and preferences relating to support. This has been shown to provide continuity and consistency of staffing, decreasing likelihood a breakdown of the person’s community accommodation and support arrangements. A member of the relevant community team (including someone with housing expertise) should be invited to ward rounds, care programme approach (CPA) meetings and multidisciplinary team meetings to ensure collaborative discharge planning. Relevant community teams could include psychological therapies, community mental health teams, community learning disability team, the learning disability intensive support team or a crisis resolution home treatment team. To support discharge, acute mental health inpatient teams (regardless of the environment) could consider ‘out-reach’ to the person in their home or community setting. Alternatively, community services could support the transfer between inpatient and the community by in-reaching into inpatient services.

Further guidelines on discharge from acute mental health inpatient settings can be found in NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults. Further information on community services and developing a robust community offer for people with a learning disability and autistic people can be found in NHS England’s community support for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults – a resource pack to support the development of local community services for adults with a learning disability and autistic adults and Meeting the needs of autistic adults in mental health services – guidance for integrated care boards, health organisations and wider system partners (2023).

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) statutory guidance on Discharge from mental health inpatient settings should be followed, with each of the key principles below being considered:

- Principle 1: individuals should be regarded as partners in their own care throughout the discharge process and their choice and autonomy should be respected.

- Principle 2: chosen carers should be involved in the discharge process as early as possible.

- Principle 3: discharge planning should start on admission or before, and should take place throughout the time the person is in hospital.

- Principle 4: health and local authority social care partners should support people to be discharged in a timely and safe way as soon as they are clinically ready to leave hospital.

- Principle 5: there should be ongoing communication between hospital teams and community services involved in onward care during the admission and post-discharge.

- Principle 6: information should be shared effectively across relevant health and care teams and organisations across the system to support the best outcomes for the person.

- Principle 7: local areas should build an infrastructure that supports safe and timely discharge, ensuring the right individualised support can be provided post-discharge.

- Principle 8: funding mechanisms for discharge should be agreed to achieve the best outcomes for people and their chosen carers and should align with existing statutory duties.

Appendix 1: How we developed this guidance

This guidance has been co-produced with people with lived experience (including NHS England’s Learning Disability and Autism Advisory Group), integrated care boards, colleagues from NHS England national teams working in related areas, and clinicians who have shared their experiences, guidance, and service models. It has been developed with NHS England regional teams, many of whom have begun to implement local versions of this guidance and contributed their expertise. The authors reviewed peer-reviewed literature, national policies, clinical guidelines and statutory guidance when preparing this guidance.

Appendix 2: National policy context

Building the right support (2015)

Building the right support and the national service model (2017) were written to support the NHS and local authorities to reduce the number of autistic people and people with a learning disability in mental health hospitals. This was to be achieved by increasing support available to people in their local community and ensuring that when people are admitted for assessment and treatment in a mental health hospital setting because their health needs cannot be met in the community, it is high quality and they do not stay there longer than they need to.

Building the right support focused on people who display behaviour that challenges, including those with a mental health condition, however this guidance is designed specifically for people with a mental health condition.

Building the right home (2016)

Building the right home (2016), which aimed to support the NHS and local authorities to enable more people to live in their own home in the community.

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019)

The NHS Long Term Plan set out a 10-year vision for improving the NHS in England including how to support adults with a learning disability, autistic adults, and autistic adults who have a learning disability to lead happier, healthier, and longer lives. It includes a commitment that, by March 2023/24:

- for every 1 million adults, there will be no more than 30 adults with a learning disability and autistic adults cared for in a mental health inpatient unit

- for children and young people under 18, there will be no more than 12 to 15 children with a learning disability, autism or both per million children cared for in a mental health inpatient facility.

The NHS mental health implementation plan (2019)

The NHS mental health implementation plan published alongside the NHS Long Term Plan commits to:

- Improving adult and older adult acute mental health services by increasing investment in the level and skill-mix of staff and improving the therapeutic offer, resulting in better patient outcomes and experience in hospital, and contributing to a reduction in avoidable length of stay by 2023/24.

- Eliminating avoidable adult acute out of area placements.

Building the right support action plan (2022)

This action plan is a cross-organisation collaboration that sets out how people with a learning disability and autistic people should be supported in a hospital or community setting, including specific commitments relating to mental health hospitals and discharge from them. Commitments from this action plan are interwoven into this guidance, and specifically into Appendix 5: supporting commissioners to develop a service specification.

Reform of the Mental Health Act

The Government’s White Paper, Reforming the Mental Health Act (2021), contained proposals to reform the Mental Health Act 1983.

The Government published a draft Mental Health Bill in 2022 outlining its intentions to make changes to the Mental Health Act. Proposals in the Bill include: limiting the grounds upon which a person with a learning disability or an autistic people can be detained in hospital under the Mental Health Act; putting Care (Education) and Treatment Reviews and (dynamic) risk registers on a statutory footing: Care (Education) and Treatment Reviews and dynamic support registers

Health and Care Act (2022)

The Health and Care Act (2022) established integrated care systems (ICSs) and integrated care boards (ICBs) across England. ICSs are partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up health and care services in the local area. They are designed to improve health outcomes for their population. Within an ICS, an integrated care board is the statutory NHS organisation that develop a plan for meeting the health needs of the population, managing the NHS component of the budget required to achieve that plan and arranging for the provision of health services.

Statutory guidance on executive lead roles on integrated care boards

This guidance, published in May 2022, says that ICBs must have an executive lead for children and young people, special educational needs and disability, safeguarding, learning disability and autism, and Down’s syndrome. It sets out how these executive leads will support the Board in carrying out its responsibilities in relation to these groups of people.

Equality Act (2010)

The Equality Act (2010) requires organisations to make reasonable adjustments where a person with a disability may be at a substantial disadvantage compared to a person without a disability. Therefore, we would expect most people with a disability to be able to access mainstream inpatient mental health services with reasonable adjustments being made as necessary.

Appendix 3: NHS England’s response to the policy context

Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Inpatient Quality Transformation Programme

The transformation programme was introduced by NHS England in 2022 with the aim of supporting cultural change and improve the quality and safety of care people experience in and across all NHS-funded mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient settings.

Programme priorities are:

- Explore and accelerate different therapeutic offers, including community-based alternatives to admission and a culture within inpatient care that is safe, personalised and enables patients and staff to flourish.

- Have a clear oversight and support structure that is sustainable and transparent, where issues are identified early. Services that are challenged will have timely, effective, and coordinated recovery support.

The programme focuses on the following themes:

- Theme 1. localising and realigning inpatient services, harnessing the potential of people and communities

- Theme 2. improving culture and supporting staff

- Theme 3. supporting systems and providers facing immediate challenges

- Theme 4. making oversight and support arrangements fit for the sector.

In addition to the 4 themes identified, the Quality Transformation Programme will build upon existing work in the field of reducing restrictive practices in inpatient settings.

One of the mechanisms to deliver the programme is to develop a suite of guidance – the Commissioning framework for mental health inpatient services – to support ICBs in commissioning mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient services: this document forms part of that guidance.

NHS England guidance for adult and older adult acute inpatient mental health services

NHS England’s acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults is national guidance about acute inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults, including people who are also autistic, have dementia, an alcohol or drug problem, a learning disability and any other individual needs. The guidance is intended to support integrated care systems and providers of mental health acute wards and psychiatric intensive care units to meet the ambitions for acute mental health care set out in the NHS Long Term Plan and NHS mental health implementation plan (2019) alongside existing legislation and acute mental health standards.

Learning disability and autism specific initiatives

Published guidance to reduce reliance on mental health inpatient care includes:

- Dynamic support register and Care (Education) and Treatment Review policy and guide which aims to prevent avoidable hospital admissions for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

- Reducing long term segregation and restrictive practice

- Green light toolkit (National Development team for inclusion, 2022) a free commissioned resource to support mental health services to make reasonable adjustments.

- Sensory friendly resource pack to support all services to consider the sensory needs of autistic people.

Appendix 4: Evidence base

In addition to the policy and legislative context, there is an evidence base which highlights the importance of developing this guidance. We have highlighted a number of key items below.

Learning disability

One study (Dodd et al, 2022) discussed the development and evaluation of a learning disability integrated intensive support service, its structure and effectiveness since its inception. It describes a model where they deliver a consistent team and an in-reach and outreach function with inpatient services. This appears to have delivered improved outcomes for people and is reflected in this guidance with recommendations for team members to work across both the community and inpatient provision for continuity. This is one interpretation of delivering not only a consistent team but an in-reach and outreach function, which appears to have delivered improved outcomes for people.

Another study (McGill et al, 2020) explored the role played by different aspects of the social, physical, and organisational environments in preventing behaviour described as challenging in people with learning disabilities. Though this primarily focusses on community provision, much of the learning is replicable for other services and has been considered here.

Autism

We know that a disproportionately high number of autistic people experience mental health problems. The 2022 GP Patient Survey found that 38% of autistic patients (with no learning disability) identified themselves as having a long-term mental health condition. This compares to 11% in the general population. Assuring transformation (March 2023) indicates that there has been an increase of 88% in autistic patients (with no learning disability) since March 2015. The size of the increase partly reflects under reporting of autistic patients and under 18s in the early stages of the data set but the inpatient trend for this group is still upward.

A recent co-produced systematic review by Loizou et al (2023) identified 29 articles relating to approaches to improving mental health care for autistic people, none of which provided conclusive evidence on effectiveness. It indicated the need for further research to be undertaken.

An online survey identified within this sought clinicians’ perceptions of ‘current practice and adaptations’ for autistic individuals admitted to hospital in the UK (Jones et al, 2021). Findings revealed that autistic individuals are not uncommonly admitted to hospital, but that mainstream mental health services have proportionately fewer available clinicians with autism expertise compared to more specialist services. 72 of the 80 services (90%) offered additional assessments for autistic individuals, and 44 of the services (55%) offered adaptations to standard provision. These have been considered within this guidance. Participants perceived that, on average, autistic individuals are more likely to have a delayed discharge and more restrictions imposed (notably, instances of seclusion and long-term segregation). Participants reported, on average, that some clinicians/services lack autism-specific training and there is not always the availability of autism-expertise.

In 2018 a qualitative study took place that focused specifically on the experiences of autistic adults admitted to hospital (Maloret and Scott, 2018). Participants reported that admissions were associated with anxiety; that there were several mediating factors for this, including the environment, ‘sensory profile’ of the ward, ease of engagement with structured activities and routines and the amount and type of social interaction they were involved in. Coping strategies reported by participants varied, but importantly, included becoming more withdrawn and isolated, eating less and engaging in deliberate self-harm; thereby, potentially increasing risk. The data suggested it could be more difficult to predict triggers for anxiety and the likelihood an individual would employ avoidance or less safe coping strategies (for example, self-harm) at the point of admission, compared to after the person had become more accustomed to the environment. This reaffirms the importance of a workforce that are aware of the needs of autistic people and for environments (physical, activities, sensory) to be in place which reduce residual anxiety.

Autism and learning disability

Recent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (Ince et al, 2022) led to development of a guide based on the experiences of 27 people, all of whom had a learning disability or were autistic, living in 3 long-stay hospitals in England. Key messages have been incorporated into this guidance such as the focus on trauma informed care, and avoidance not labelling people/ putting in people boxes.

Appendix 5: Things that need to happen for an adult with a learning disability or autistic adult during their inpatient journey

As well as the key actions listed below, if someone is detained under the Mental Health Act, then Mental Health Act legislation and the accompanying Code of Practice must be followed. If someone is deemed to not have mental capacity to make specific decisions, then the Mental Capacity Act and accompanying Code of Practice must also be followed. All other relevant legislation and guidelines must also be followed.

From the point of presentation to within 72 hours of admission