Foreword

From Steve Russell, Chief Delivery Officer and National Director for Vaccinations and Screening, NHS England

I am very pleased to be able to share with you the NHS vaccination strategy which brings together all vaccination programmes, for the first time, to protect communities and save lives.

In my previous role as chief executive of an acute hospital trust, I saw the consequences of disease and ill health every day. I saw how some populations experienced inequalities in their access to and outcomes from healthcare. I also understood the enormous impact that vaccination had on people’s lives and the importance of the NHS’s work in delivering them, alongside our partners. That is why I’m so excited that we have worked with such a wide range of skilled and passionate stakeholders to develop an NHS strategy to further harness the power of this extraordinary intervention, for all communities.

The strategy was borne from several different drivers. Our world-leading NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme allowed us to be transformative in our approach, engaging with communities in a way that we had never done before. We also have the opportunity to learn from our other immunisation programmes – to reduce the decline in take-up of life-course vaccinations, such as MMR. We must do this in a way that gives local systems the ability to build an effective, flexible, integrated, local delivery network for vaccination in collaboration with a range of local partners.

I want the publication of this strategy to start a conversation, within integrated care boards (ICBs) and the wider health and care system, about how we can use vaccination to deliver holistic, person-centred, preventative care via flexible teams that span primary and community care as well as other sectors. This should be an opportunity for all of us to consider how well we are meeting the needs of our whole populations including adults and children that may be underserved by current services, and use vaccination to help address health inequalities. There is more we need to do with our partners to build confidence and encourage people to come forward for these life-saving services. Our vaccination strategy builds on our collective learning and outlines three clear priority areas, including:

- Improving access including an expansion of online services: The ‘front door’ to vaccination services should be simple to understand. Many more people will be able to book their vaccines online quickly and easily, including via the NHS App. Families will be able to view their full vaccination record with clear information and guidance on what vaccinations they should have to keep them well

- Vaccination delivery in convenient local places, with targeted outreach to support uptake in underserved populations: It should beeasy for people to take up the vaccination offer, with sites at GP practices and pharmacies as well as shopping centres, supermarkets and community centres. Bespoke outreach services should be tailored to communities that are un- or under-vaccinated, building trust and confidence.

- A more joined-up prevention and vaccination offer: Vaccination services and activities should be holistic, offering multiple vaccinations for the whole family where appropriate, including covid and flu alongside, for example, opportunistic MMR and HPV catch up. Multidisciplinary teams could offer wider health advice and interventions such as blood pressure, diabetes and heart checks, or mental health and dental information.

We want to work with our partners to further develop the proposals in our report and ensure they improve access, experience and outcomes whilst building on what already works well locally. But I hope that all stakeholders will be inspired by the strategy to start conversations and to make improvements, immediately.

I am clear that the proof of our vaccination strategy’s success will be in its ability to stop the spread of infections such as measles, bring us one step closer in our efforts to eliminate cervical cancer, and in helping to prevent as many people as possible becoming seriously unwell and hospitalised over winter.

The development of the strategy would not have been possible without the expertise of our collaborative partners and a wide-range of stakeholders involved in designing and delivering vaccination services in local communities, including the public. The detailed engagement we received helped us shape our proposals. In addition, my colleagues in NHS England regional teams were pivotal to the development of the recommendations, including working with their ICB colleagues to gather views and examples of good practice.

Local health and care systems will be key to delivering this vision and I am looking forward to working together to implement this strategy, and to help people live longer, healthier lives.

From Dame Professor Jenny Harries, Chief Executive of the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA)

Vaccination is one of the most effective public health interventions in the modern era. Childhood vaccines alone prevent between 3.5 and 5 million deaths every year across the globe. The UK has much to be proud of – our immunisation programmes are some of the most comprehensive in the world, protecting citizens through every stage of their lives from birth to old age, and preventing deaths from deadly infectious disease.

UKHSA welcomes this new strategy, and it arrives at an important time. Over the past decade, uptake of most vaccination programmes in England has fallen, with our highest immediate concern being the decline in MMR vaccine coverage. Reversing these downward trends and addressing challenges around vaccine confidence and accessibility are critical to preventing deaths and hospitalisations from vaccine-preventable diseases. I am therefore excited to see this strategy’s renewed focus on innovative delivery approaches that respond to local people’s needs.

Within UKHSA we will continue to have a relentless focus on realising the potential of vaccines to transform the nation’s health, working hand in hand with new NHS delivery approaches. UKHSA’s scientific and research functions will work to drive innovation, and vaccine development collaborating with industrial partners help inform future evidence-based vaccine policy and promote effective programme implementation. Through our Vaccine Development and Evaluation Centre we are simultaneously supporting the development of the vaccines of the future and increasing the nation’s preparedness for future health threats.

UKHSA will continue to support the NHS through provision of authoritative clinical guidance and coordinated procurement and supply of these life-saving vaccines. Our surveillance and analysis functions will help to ensure we use the best vaccines, at the optimal schedule, and continue to shine a spotlight where poor health outcomes can be reversed. We are committed to tackling the challenge of health inequalities, working with communities and colleagues in local government to develop tailored outreach services, and harnessing the new focus within integrated care boards.

The development of our vaccination programmes is a key priority for UKHSA and will take a concerted effort across the entire health system. We will continue to work with NHS England to achieve this goal, and I urge colleagues at all levels, nationally and locally, to join forces with us to do the same.

Note from Rt Hon Patricia Hewitt, Chair, NHS Norfolk and Waveney Integrated Care Board, and Adam Doyle, Chief Executive Officer, NHS Sussex and National Director for System Development, NHS England

Since integrated care systems (ICSs) were placed on a statutory footing, we have both seen first-hand the significant progress that systems are making. When the Fuller Stocktake, Next steps for integrating primary care,1 and the Hewitt Review, An independent review of integrated care systems,2 were first published, we knew that significant change would be required from all parts of the health and care system. Change is never easy, particularly in these challenging times. But we have both been struck by how much this strategy, Shaping the future delivery of NHS vaccination services, builds on the delivery models of Fuller and the ways of working through systems proposed by Hewitt. We particularly welcome the way this approach to vaccination services has been developed through significant and far-reaching engagement with partners in local systems committed to meeting the needs of their populations, provide proactive, personalised care and help people stay well for longer.

The recommendations in this strategy build on work already underway in systems across the country. They offer the opportunity to deliver life-saving vaccination programmes through integrated neighbourhood, place and system teams, with primary care at their heart. By bringing together the full range of partners in ICSs, these integrated teams can support the delivery of an even wider set of prevention services and help us prepare for future pandemics. We are particularly pleased to see the emphasis on working with underserved and marginalised communities – vital if we are to tackle persistent and unacceptable health inequalities – as well as the intention to delegate commissioning to integrated care boards.

We hope that colleagues in England’s 42 ICSs will welcome this opportunity for local leaders and partners to make an even bigger difference to the people they serve.

Summary

Vaccination saves lives and protects people’s health. It ranks second only to clean water as the most effective public health intervention to prevent disease.3 Through vaccination, diseases that were previously common are now rare, and millions of people each year are protected from severe illness and death. In the last two and a half years, COVID-19 vaccines have saved tens of thousands of lives in England.

England has historically performed well across both life-course and seasonal vaccinations and has effectively responded to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease. We achieve among the highest rates of flu vaccination in the world;4 our NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme is rightly held up as a success after delivering over 156 million vaccinations to date;5 and it is estimated that the introduction of HPV vaccination for school children could prevent over 110,000 cases of cancer by 2058.6

In recent years, however, our performance has been in decline. We have not hit population coverage targets for childhood immunisations. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the UK had eliminated measles in 2016 but we have since lost this status.7 We do not perform well everywhere, with significant variation in uptake and coverage between different communities that can often reflect wider health inequalities. For example, MMR vaccination rates across local authority areas in England vary by as much as 22%.8 Urgent action is required on the part of local health and care systems to bring parity to all vaccination programmes, given that in recent years the population and the NHS has necessarily focussed on COVID-19 vaccinations.

NHS England is now considering how it integrates the NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme with more longstanding vaccination programmes to create a more cohesive approach, building on many decades of successful immunisation delivery as well as lessons of the last three years. In doing so, we will aim to not only increase overall uptake and coverage of vaccinations, but to reduce disparity in uptake, so that every community in the country has the protection it needs. We also need the flexibility to respond to future challenges, recognising that the nature of the diseases we face will evolve. This will be underpinned by a technology and data infrastructure that enables the public and healthcare providers to understand vaccination status and take action to improve it.

In 2019 the Government’s manifesto committed to continue to promote the uptake of vaccines via a national vaccination strategy. In developing that strategy, NHS England has sought the views of a wide range of stakeholders and the public. Their input has been invaluable in describing what we need to retain from our current approach, and how we can improve and adapt it to ensure it meets everyone’s needs. Different approaches will be needed for vaccines that are given every year to eligible people, those given to everyone at a certain age or point in their life, and those given in response to outbreaks of infection and disease.

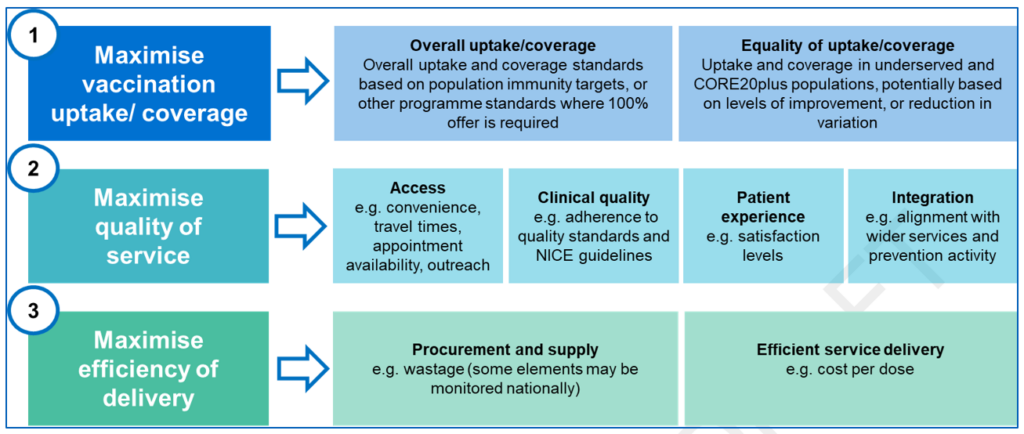

Our future approach to vaccination will focus on outcomes – reducing morbidity and mortality by increasing vaccination uptake and coverage. To achieve this goal, every system in the country will need vaccination services that:

…are high quality, convenient to access and tailored to the needs of local people

The ‘front door’ to vaccination services should be simple to understand. Everyone should have easy access to safe, high quality vaccination services in convenient settings that are designed to meet the needs of the local population. People should be supported to understand the vaccinations for which they are eligible, consent to receive them, and be able to book an appointment quickly and easily, either online or over the phone.

…are supplemented by targeted outreach to increase uptake in underserved populations

Outreach services should actively seek those people and communities with low vaccine uptake and coverage, building trust and providing services that meet the needs of communities, in particular those experiencing health inequalities.

…are delivered in a joined-up way by integrated teams, working across the NHS and other organisations, to improve patient experience and deliver value for money

Making vaccination a central role of integrated neighbourhood teams (as described in the Fuller Stocktake 9) could support a more joined-up offer to the public, alignment with other prevention services and joint working with other sectors. The vaccination event could play a greater role in promoting and delivering other evidence-based public health interventions to adults, children and young people; similarly, other contacts with health and care services could be used to promote vaccination, aligned with wider person-centred healthcare delivery.

This approach will need clear leadership and a strong and engaged workforce. Systems should be given responsibility and flexibility to design and deliver vaccination services to meet their population needs, commissioning the optimal provider network and continuing to use the expertise of primary care.

We will continue to work with stakeholders to refine a streamlined set of outcomes and standards so that systems know what they need to achieve, and determine the financial and contractual frameworks required to support delivery.

Working with partner organisations, we will ensure that vaccine supply works in a way that is efficient and convenient for providers, and supports greater co-administration of vaccines where appropriate.

We will continue to enhance digital services, improving access to timely, high quality data, expanding the use of national booking systems and creating a national vaccination data record.

As well as improving population health, every additional vaccination is a potential illness averted or life saved. Our offer needs to be as efficient, cost-effective and sustainable as possible, while recognising that these highly effective preventative services deliver considerable downstream benefits. The way that vaccines are made, supplied and administered will change – for example combination vaccines – and this requires a new model and a fresh approach, delivered through local systems using their allocated resources to address public health and inequalities.

We intend to progress these proposals at pace and fully implement the strategy by 2025/26. Some proposals will require further discussion with partners and/or legislative change. Others will require testing, and we will continue working with integrated care systems (ICSs) to further assess and evaluate them. We look forward to working with all our partners – in the NHS, local government and beyond – to take our proposals forward.

Our proposals

This strategy is for people and organisations involved in the commissioning, planning and delivery of NHS vaccination services in England.

The tables below summarise the proposals we set out in this strategy, together with the responsible organisation. Note that where an action is stated for integrated care boards (ICBs), in some cases this is subject to the delegation of the appropriate functions and powers from NHS England.

Theme 1: Simple, convenient and efficient front door to service

| Proposal | Section | Action by:[10] |

|---|---|---|

| Help people understand why they or their families need a vaccination and how to access it, working at national and local level to build trust and confidence, eg making booking invitations and reminders more personalised and accessible, and using nationally co-ordinated invitations to complement local activity where appropriate. | 3.1.1 to 3.1.3 | NHS England, DHSC, UKHSA and ICBs |

| Explore use of the NHS App to improve the experience of booking a vaccination and understanding individual vaccine histories. | 3.1.4 | NHS England |

| Test the viability of extending online booking further – initially to adult life-course vaccinations – and expanding National Booking Service (NBS) to provide information on walk-in services. | 3.1.5 to 3.1.6 | NHS England |

| Explore alignment of providers’ existing clinic booking systems with a national system to simplify access to appointments. | 3.1.6 to 3.1.7 | NHS England |

| Where clinically appropriate and operationally feasible, make co-administration of seasonal vaccinations the default model and more cost-effective, resulting in increased uptake. | 3.1.8 | ICBs |

| Provide a universal, core offer in a consistent location/setting to increase efficiency and capitalise on public understanding of ‘where to go’ for vaccinations. | 3.1.9 to 3.1.13 | NHS England and ICBs |

| Tailor the core offer for the local population and ensure core settings are not the only place to get vaccinated. | 3.1.14 to 3.1.15 | ICBs |

| Enable local flexibility to determine the provider network that delivers this offer. | 3.1.17 | NHS England and ICBs |

Theme 2: Targets underserved populations through data-driven, focused outreach

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Work with local authorities, directors of public health and voluntary organisations to take responsibility for planning outreach services that meet the needs of their underserved populations and address wiser health inequalities. | 3.2.2 | ICBs |

| Ensure the outreach offer is an integrated part of a system’s vaccination delivery network to enable co-ordination and oversight across all services. | 3.2.5 | ICBs |

| Continue to evaluate the impact on uptake, cost-effectiveness and patient experience of different outreach approaches, seeking to define value for money. | 3.2.7 | NHS England and ICBs |

| Ensure timely and accurate data is available from GPs and other providers to improve availability of uptake and coverage data for all vaccinations and timely data flows. | 3.2.8 | NHS England |

| Consider, in local vaccination strategies developed with local government, how to use community assets and facilities to maximise vaccination uptake in underserved populations and reach into local communities, considering vaccination alongside wider health, care or social issues. | 3.2.9 to 3.2.14 | ICBs |

| Build on the partnerships with underserved communities developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure communication strategies are informed by community insight. | 3.2.15 | NHS England and ICBs |

Theme 3: Integrated, multidisciplinary teams

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Make vaccination a fundamental part of primary care network (PCN)-level integrated, multidisciplinary, flexible teams, as proposed in the Fuller Stocktake, with these working collaboratively across the whole vaccination network and delivering other healthcare interventions alongside vaccination and when not vaccinating. | 3.3.1 to 3.3.4 | ICBs |

| Structure vaccination delivery in a way that promotes health and allows those delivering vaccination to offer a wider set of preventative interventions, such as blood pressure checks, based on population need. | 3.3.6 and 3.3.7 | ICBs |

| Integrate vaccination in existing clinical pathways through joint working with local providers, including primary care, acute, community, mental health/learning disability and local authorities. | 3.3.8 | ICBs |

| Help make vaccination the business of everyone working in patient-facing roles through training and awareness campaigns and widening the roles that can vaccinate to increase the number of vaccinators. | 3.3.8 | NHS England and ICBs |

Theme 4: Strong system leadership

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Clarify responsibility for vaccination strategy and delivery across ICBs and integrated care partnerships (ICPs), working with local authority partners, UKHSA and other experts to ensure all eligible people receive a meaningful vaccination offer. | 4.1.2 | NHS England and ICBs |

| Include vaccination in integrated care strategies and joint forward plans | 4.1.2 | ICPs and ICBs |

| Pursue, subject to the appropriate processes and assessment of readiness, delegation of vaccination commissioning responsibility to ICBs, with the intention that all ICBs take this on by April 2025. | 4.1.3 and 4.1.4 | NHS England and ICBs |

| Maintain overall accountability for vaccination services within NHS England and retain national responsibility for functions that are best ‘done once’. | 4.1.5 | NHS England |

Theme 5: A new commissioning and financial framework

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Provide common outcomes and standards for systems to meet that maximise uptake and coverage in the general population and address access disparity in underserved communities. | 4.2.2 and 4.2.3 | NHS England |

| Streamline quality assurance processes to reduce the burden on providers. | 4.2.4 | NHS England |

| Give systems flexibility to commission an integrated, collaborative vaccination delivery network across all vaccinations, including seasonal, life-course and outbreak response, that best meets the needs of their population. | 4.2.5 and 4.2.6 | NHS England and ICBs |

| Develop materials to support the commissioning and contracting changes that underpin the proposals in this strategy | 4.2.7 | NHS England |

| Explore and engage on changes to vaccination financial arrangements that increase system-level flexibility. | 4.2.10 to 4.2.15 | NHS England |

Theme 6: An integrated flexible vaccination workforce

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Develop a vaccination workforce with a skill mix that makes best use of trained, unregistered staff where clinically appropriate and subject to the appropriate legislation, and focuses registered staff on activities where they can bring most benefits including delivering other health and wellbeing interventions alongside vaccination | 4.3.2 to 4.3.4 | ICBs |

| Support the wider use of the national workforce protocol for seasonal vaccination. | 4.3.5 | NHS England |

| Explore options to revise regulations that may widen opportunities for experienced, non-prescribing healthcare professionals to vaccinate by allowing delegation of vaccination to unregistered staff. | 4.3.5 | NHS England with UKHSA, DHSC and MHRA |

| Work with the royal colleges, GMC, other relevant bodies and local authorities to explore how vaccination can be a more prominent part of training for all staff. | 4.3.5 | NHS England |

| Grow a diverse workforce that reflects the community it serves, provides NHS career entry points, including for volunteers, and enables career progression to support retention. | 4.3.6 to 4.3.8 | ICBs |

| Develop workforce management arrangements that enable staff to work flexibly across the vaccination delivery network and ensure there are sufficient trained staff to manage outbreaks and surge. | 4.3.9 | ICBs |

Theme 7: Timely and accurate data

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Create a national vaccination data record to improve availability of timely, accurate data across all vaccination programmes and enable use of national capabilities, such as invitations and bookings, for a wider set of vaccinations and outbreak response. | 4.4.5 | NHS England |

| Make it easier for healthcare workers to capture vaccination event data, including increased automation. | 4.4.6 | NHS England |

| Increasingly enable people to access their own vaccination data via the NHS App. | 4.4.7 | NHS England |

Theme 8: Efficient and responsive vaccine supply

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Explore consolidation and alignment of vaccine supply chains to support greater uptake and efficiency where beneficial. | 4.5.5 | NHS England working with DHSC, UKHSA and ICBs |

| Consider the potential impact of centralising the procurement of adult flu vaccine on systems’ ability to flex their delivery network. | 4.5.6 | NHS England with DHSC and UKHSA |

| Support the future vaccine pipeline by maximising NHS support for vaccine clinical trials, including working with the new Clinical Trials Delivery Accelerators and exploring strategic partnerships with the commercial sector to strengthen our onshore supply and pandemic response. | 4.5.8 | NHS England with DHSC and UKHSA |

Theme 9: Outbreak response capability

| Proposal | Section | Action by: |

|---|---|---|

| Ensure ongoing ability to respond to outbreaks and pandemics through integrated neighbourhood teams. | 4.6.13 | ICBs |

| Develop a robust, multi-agency plan for disease outbreaks (including vaccine-preventable diseases) so systems can rapidly and efficiently mobilise increased capacity and limit impact on other services. | 4.6.13 | ICBs with UKHSA and other partners |

| Develop service specifications, tools and guidance for dealing with outbreaks. | 4.6.14 | NHS England with UKHSA |

1. Introduction

1.1 How we have developed this strategy

1.1.1 We have engaged widely with integrated care systems (ICSs), general practice and community pharmacy, NHS trusts, professional bodies, charities, private sector organisations, clinicians, local authorities, directors of public health, UKHSA and the public via a citizen survey.

1.1.2 This strategy sets out our proposals in view of this engagement. It also builds on the 2019 Vaccinations and Immunisations Review, recommendations from professional bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) strategic plan which outlines UKHSA’s overarching priority of achieving improved health outcomes through immunisation, including driving innovation and growth in the life sciences industry.

1.1.3 The strategy covers vaccinations for which the NHS has delivery responsibility, including all those in the routine immunisation schedule for infants, children, young people, adults and pregnant women, selective vaccinations for those at risk, COVID-19 vaccinations and seasonal influenza vaccinations. Other vaccines in development including those for cancer and personalised, and those currently deployed for travel or in a private market are not covered.

1.2 Terminology

1.2.1 We refer to ‘vaccination’ or ‘immunisation’. Vaccination is the act of administering the vaccine, while immunisation is the process by which an individual achieves immunity. While the two terms are not interchangeable, ‘vaccination’ is more meaningful to the public and we have used it in much of our engagement work to date.11

1.2.2 The term ‘seasonal vaccinations’ includes flu vaccination and COVID-19 vaccination. We do not yet know whether COVID-19 will be a seasonal vaccination in future but include it within this term to differentiate it from life-course vaccinations.

1.2.3 The term ‘life-course vaccinations’ refers to those in the UKHSA complete routine immunisation schedule for all ages, which includes routine immunisations, selective immunisations and additional vaccinations for individuals with underlying medical conditions.

1.2.4 Co-administration means providing more than one vaccine in the same appointment.

1.2.5 ‘Outbreak’ refers to vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) outbreaks.

2. Why do we need a strategy for the delivery of vaccination services?

2.1 The importance of vaccination

2.1.1 Vaccinations prevent up to three million deaths worldwide every year and help many more people to avoid a stay in hospital.12

2.1.2 VPDs can cause long-term illness, hospitalisation and death. Infections such as polio, Hib and measles have been, and still have the potential to be, serious health problems in this country, causing complications and early death in children and adults.

2.1.3 High vaccination rates prevent the spread of these diseases and protect vulnerable individuals for whom vaccination is not safe and/or effective. Wider benefits include helping children to stay in school and freeing up NHS resources to support other patients.

2.1.4 Some vaccines, such as for HPV, also prevent cancer. Increasing uptake of HPV vaccination in young people is critical to our ambition to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040, and we know it has already helped to drastically reduce the incidence of this disease.

2.1.5 Our population benefits from vaccination services that are safe and effective. The UKHSA routine immunisation schedule, as well as selective NHS immunisation programmes, now protect against diseases that were once responsible for significant morbidity and mortality.13

2.1.6 All healthcare workers and many sections of the public, including certain age categories, pregnant women and people with some medical conditions, are offered a free flu vaccine to protect them in the winter months.

2.1.7 Overall, tens of millions of people each year receive vaccinations when they need them, delivered by a range of trusted providers, including general practice, community pharmacy and school aged-immunisation services (SAIS) providers.

2.2 Building on our successes

2.2.1 In England we achieve high uptake for both life-course and seasonal vaccinations – over 90% for pre-school diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis and among the highest in the world for flu vaccination.14, 15 The NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme has been the biggest vaccine drive in the history of the NHS – implementing the largest volume of novel vaccines in the shortest time, and repeatedly with boosters. As of November 2023, it has delivered over 156 million16 total vaccine doses and saved many lives.

2.2.2 The NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme required new roles, responsibilities and operational processes, and succeeded through the hard work of the NHS, local government, the voluntary sector and other partners. It also drove innovation and investment in service delivery, including the use of pop-up and walk-in sites, maximising the contribution of volunteers, working with community leaders to build trust and creating national booking systems.

2.2.3 We need to consider where there is room for us to improve:

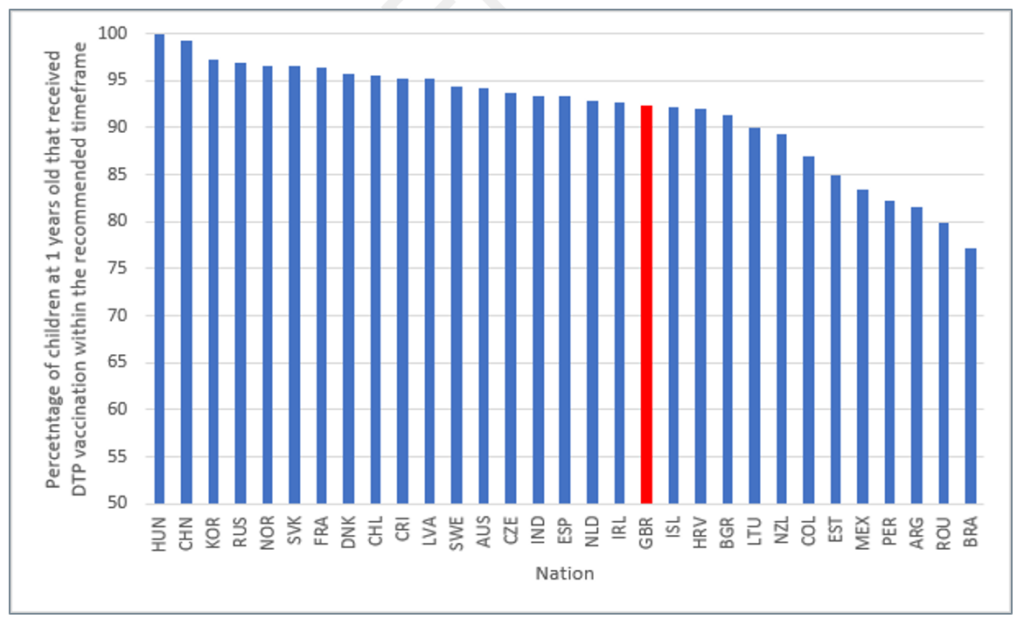

- Nationally we have seen a 10-year decline in pre-school immunisations and coverage and while remaining high rates are lower than the WHO-specified threshold for many vaccines and lower than in other advanced economies (see Figure 1 below). Below-threshold coverage risks outbreaks, as we have seen for measles, and the return of diseases not seen in the UK for a generation.

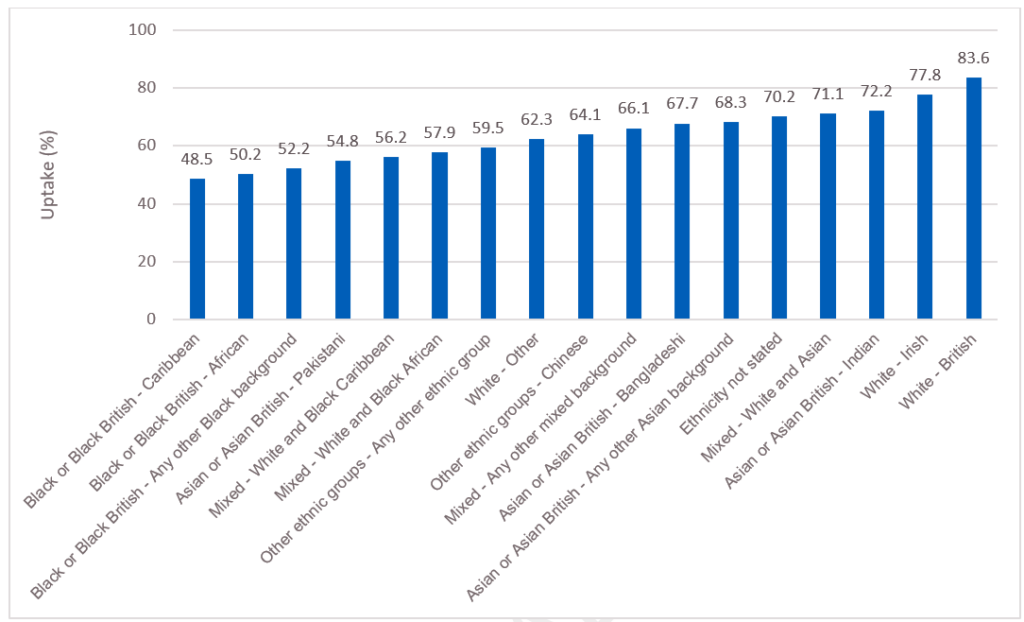

- We know that the headline data masks significant disparity in uptake. We need to maximise uptake and coverage in every area of the country for all communities, particularly among deprived communities, minority ethnic groups (see Figure 2 below), inclusion health groups such as people who experience homelessness and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, and those not registered with healthcare providers. We also need to ensure we support people with weakened immune systems to receive the vaccinations they need.

Figure 1: Childhood vaccination rates for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis among OECD countries in 202217

Source: OECD (2023) Child vaccination rates (indicator)

Figure 2: Over 65 uptake of flu vaccination by ethnic group in England, 2022 to 2318

Source: UKHSA (2022; last updated 23 March 2023) Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in GP patients: monthly data, 2022 to 2023.

2.2.4 Recent outbreaks, including of lesser-known diseases such as mpox, remind us of the ever-evolving nature of infectious disease. We need to ensure that – across the NHS and other national and local organisations – we are prepared to respond effectively to new threats, as well as to implement new vaccines and other technologies as they are developed, for example, options for potential RSV and varicella programmes.

2.2.5 The emergency response to COVID-19 meant that the NHS vaccine deployment programme needed to operate relatively independently from other NHS vaccination programmes. We now need to bring the operating model for COVID-19 vaccination alongside our other programmes, in particular for flu, which may be offered to similar cohorts at a similar time of year. And in doing so, we will take account of both our experience providing vaccinations over many decades and what we have learnt since administering the world’s first COVID-19 vaccine outside a clinical trial in December 2020.

2.2.6 The public will expect us to achieve the maximum value for every pound we spend on vaccinations, optimising investment, supporting innovation and delivering continuous improvement. If we are to innovate and invest in some areas, we need to consider collectively how we can be more efficient in others while still addressing local population health needs.

2.2.7 To make a real impact on uptake and coverage, we will need to:

- build on what has been working well – continuing to provide accessible and convenient services, making sure the fundamentals are in place everywhere and driving efficiency wherever possible

- do more to reach those who are currently underserved, including through new service models, better targeting of resources to local needs, and action across the NHS and its partners to build trust.

2.3 What we have heard

2.3.1 We asked stakeholders what the key components of a future vaccination offer should be. The feedback we received covered support for:

- A continued, concerted effort to reduce disparities in uptake and coverage.

- An offer that is convenient for the public, including easily accessible locations, flexible opening hours, systematic call and recall, and streamlined and flexible booking.

- Outreach’ services as part of a wider health and care offer, and a sustained effort to build trust with underserved communities.

- Strong local leadership for vaccination and flexibility to design services that are culturally sensitive, meet the needs of local populations with expert public health input, and delivering clearly defined outcomes.

- Clear and balanced national and local communication, tailored to individual needs where appropriate, to explain the value of vaccinations and what is available to people, and address vaccine hesitancy.

- A sustainable multidisciplinary workforce that can adapt through the annual vaccination cycle, making use of registered and unregistered practitioners as appropriate. Staff who reflect the population they serve and have the confidence and training to answer questions from the public.

- Data and technology use to improve services, including with the flow of timely data across all vaccination services.

- More joined-up, collaborative working between NHS providers and the wider NHS, local government and other partners to support delivery to all parts of local populations.

- Development of further enablers for the above, including a commissioning and financial framework that supports the delivery approach (subject to usual engagement with professional bodies and other bodies) and an efficient and effective supply of vaccines.

3. Vaccination delivery networks

3.1 A simple and convenient vaccination ‘front door’

3.1.1 Members of the public told us how important it is that vaccination services are accessible and convenient. The evidence also tells us that convenience can overcome vaccine hesitancy and promote access by underserved groups.19 ,20 This means providing a ‘front door’ to vaccination that makes it as easy as possible for people to understand why they should have a vaccine, know where and how to get it, book an appointment if one is necessary and get to the location of the services. This applies to routine vaccinations such as pre-school, seasonal vaccinations such as flu, as well as selective programmes such as hepatitis B vaccination for babies of mothers with chronic hepatitis B infection.

Case study: Increasing uptake of pre-school vaccinations in Thames Valley

In January 2020, uptake levels for pre-school booster vaccinations were low across GP practices in Thames Valley, with 27 practices having <80% uptake. Working with local practices, SILS and local public health consultants, NHS South Central and West’s Improving Immunisation Uptake (IIU) and Child Health Information Services (CHIS) teams identified communication and accessibility as the main barriers to uptake.

To tackle these access challenges, GP practices extended appointment times to make it easier for parents to attend appointments with their children, and called parents the day before their child’s appointment, reassuring them that it would be safe to come to the clinic during lockdown. Clinic staff contacted parents who missed their child’s appointment, to talk through any concerns about the vaccinations and to offer an alternative slot.

By building touchpoints with parents, including those who missed their child’s appointment, GP practices simplified the vaccination service for local families. Between January and November 2020, the number of GP practices with >90% uptake for pre-school age boosters increased from 74 to 97, and those with <80% uptake decreased from 27 to 5.

Understanding benefits of and eligibility for vaccination

3.1.2 People told us that they wanted information about vaccines from trusted sources that helped them make informed choices and feel confident about vaccination.21

3.1.3 We will explain to people the benefits of vaccinations and how they can access them, through clear and consistent communication. Nationally, this will include:

- Expanding the use of national invitations and reminders to more vaccinations, where operationally appropriate and good value for money.

- Increasing and improving the use of personalised and accessible content in invitations and other vaccination materials; for example, in alternative languages or recorded audio format.

- Working with government and other agencies to promote understanding of the importance of vaccination, building on increased awareness of vaccination following the COVID-19 pandemic and targeting vaccine mis- and dis-information.

- Identifying barriers to vaccination including among parents in relation to childhood vaccinations including HPV.

- Streamlining communications about seasonal vaccinations, learning from the joint flu/COVID-19 campaign in autumn 2022/23, and raising awareness among other audiences including pregnant women and families with young children.

- Looking at how e-consent can be used more extensively in some settings to make it easier for parents and carers to give consent for their children to be vaccinated.

- Supporting the role of Child Health Information Services (CHIS) in promoting understanding of children’s eligibility for vaccinations, digitising Personal Child Health Records and signposting to further information on vaccine eligibility.

3.1.4 We will explore how we can use the NHS App to join up user journeys for adults, children and young people, including access to vaccination records, invitations to book a vaccination, in-app bookings and appointment notifications.

Case study: HPV, polio and tetanus school vaccinations in Trafford

The School Health Service in Trafford Local Care Organisation (TLCO) provides community services for Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, including delivering vaccinations to year 8 and 9 children at schools in Trafford. This covers vaccinations to around 21,000 pupils across 19 secondary schools. One TLCO team based in a school noticed that they were consistently receiving low numbers of consent forms from parents allowing their children to be vaccinated at school (30 out of c170, approximately 17%). Following nudge calls to outstanding parents in 2022/23, the school and public health nurse team heard many parents say that they didn’t understand what HPV, tetanus and polio vaccines were for and why their child needed them. Language barriers were also an issue, with many families across the school’s catchment area speaking Urdu, Punjabi and Farsi.

To tackle this, the school and TLCO team attended a parents evening in May 2023 at the school to provide information on the vaccinations available for teenagers and why they are important, and consent forms for parents to complete at the event. Posters and leaflets in alternative languages (Urdu, Punjabi and Farsi) were displayed and interpreters were on hand to translate.

Providing this targeted support to parents proved to be successful, with 47 consent forms completed on the evening alone. This approach will be replicated in other schools in Trafford that have a low vaccination uptake.

Booking an appointment

3.1.5 The ability to book vaccinations easily, including through a national digital service, contributed to the high uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination.22 Given other demands on their time, many people will only prioritise vaccination if it is easy for them to book an appointment.23

3.1.6 To help people find appointments for vaccinations, we will work with general practice and community pharmacy to test the further extension of the existing online booking capability used for COVID-19 vaccination:

- We have already extended the National Booking Service (NBS) to support people to book a flu vaccination and provided combined COVID-19 and flu co-administration appointments and made these available on the NHS App. An additional 2,000 community pharmacies are also now using NBS to provider greater access to vaccination.

- We will go further in 2024/25, extending online booking to adult life course vaccinations in the first instance and enabling people to book on someone else’s behalf or for a family group.

- We will involve the public and providers in this process to ensure appointments are easy to access while minimising administrative burden. In parallel we will ensure the availability and explore the expansion of alternative services for those who prefer not to or cannot use online services.

- In 2025/26 our ambition is to use the NHS App to streamline access to a wider group of vaccinations for adults, children and young people, including invitations to book a vaccination, in-app bookings, appointment notifications and access to vaccination records.

- We will improve user experience by simplifying access to appointments, supporting group bookings and same day cancellations, and better meeting accessibility requirements. We will explore aligning providers’ existing clinic booking systems with a national system to simplify access to appointments.

- We will publish information on availability of walk-in services on the NBS website.

3.1.7 We will support people to find and arrange local appointments for vaccinations that can be accessed year-round, such as childhood vaccinations and catch-up of missed vaccinations:

- We know existing providers often use local booking platforms for their wider services and want to support continuity and consistency of appointment management for the workforce. As such, we propose that national booking should complement, not replace, local booking services in the short-term.

- We will explore aligning our national booking platform to a common standard, creating the opportunity for a single channel to present appointments from different booking services (whether national or local), making public access to local appointments easier.

3.1.8 Where clinically appropriate, operationally feasible and preferred by patients, co-administration of vaccines should be the default model.24 This is already the case for many childhood vaccines and should be so for flu and COVID-19. We will also explore the potential to apply this to other vaccinations in future, increasing efficiency, streamlining the experience for the public and providing opportunities to maximise uptake.

Accessing vaccination

3.1.9 We propose that systems design a vaccination delivery network or networks that deliver life-course and seasonal vaccinations, as well as outbreak response and catch-up campaigns, through the locations and settings that will best meet the needs of their population.

3.1.10 We propose that this network has several linked components:

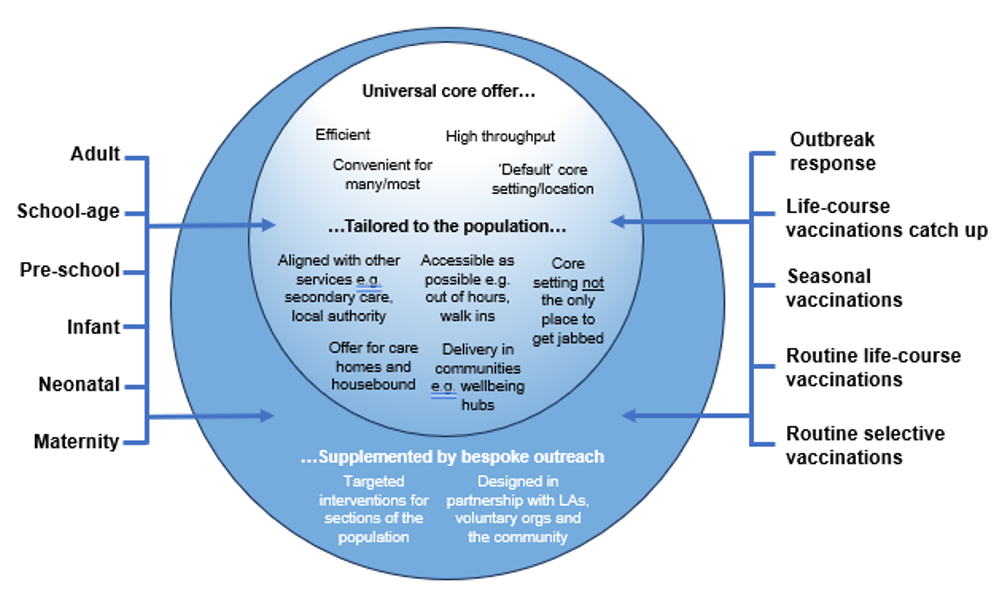

- A ‘standard’ core vaccination offer that will reach most of the population efficiently and is…

- Tailored to local communities to widen the places in which vaccination is available and ensure everyone eligible is reached.

- Supplemented by bespoke, targeted outreach interventions for specific populations currently underserved by vaccination services.

Figure 3: Core offer, tailored to the local population, supplemented by outreach services

3.1.11 Many networks will be able to reach most of the eligible population through a consistent, core location or setting where the public can expect to go to access certain types of vaccination. The core offer refers to the physical setting where the vaccination is administered rather than provider type.

3.1.12 Specifying a consistent location or setting for the core offer can help by:

- Making it clear to people where they can consistently access individual vaccinations, because the setting will be broadly the same across the country.

- Using locations where people are already accessing services (such as GP surgeries) or where large numbers of people who are eligible for particular vaccinations come together (such as schools).

- Enabling more efficient staffing models and vaccine supply routes.

- Keeping, and building on, current expertise in vaccination delivery; for example, the expertise of practice nurses in vaccinating babies and young children.

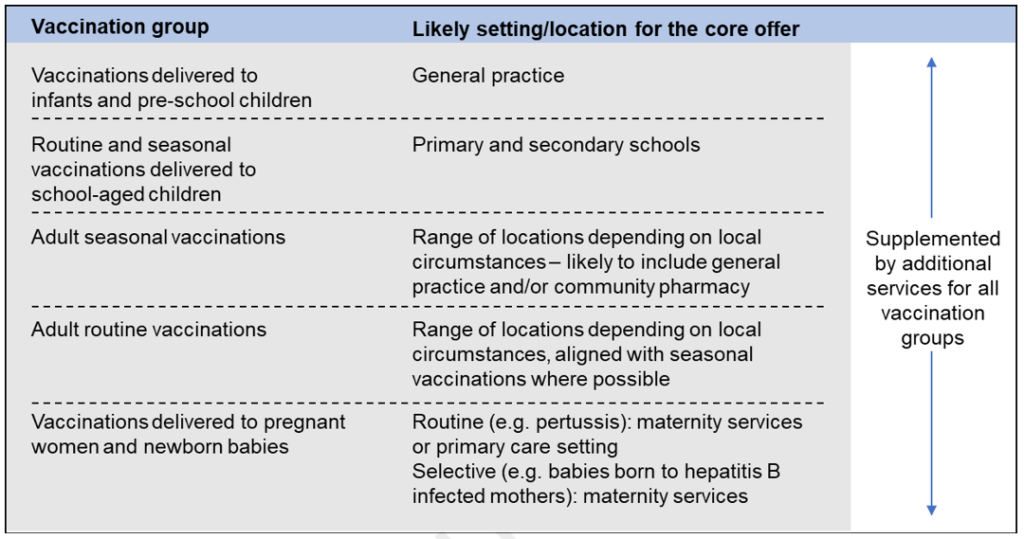

3.1.13 Most systems are likely to use the following ‘core’ settings for each group of vaccinations.

Table 1: Core settings for vaccination groups

These ‘core’ settings will be supplemented by additional services for all vaccination groups.

3.1.14 As set out in Figure 3, even the core offer should be tailored as far as possible to meet the needs of the local population, and the locations in Table 1 should not be the only place to access vaccination. If parents, for example, do not respond to invitations from the GP surgery to make an appointment for their baby to be vaccinated, it should be possible for that vaccination to be carried out, if appropriate, on a visit to an emergency department or outpatient clinic or during a stay on a paediatric ward.

3.1.15 Systems may want to consider the following actions to increase the reach of the core offer:

- Enabling vaccinations to be provided in secondary care settings for adults, young people and children where this will improve uptake of vaccination.

- Running walk-in clinics, and clinics at different times of the day and out of hours.

- Providing national and local invitations to, and information on, vaccinations in an individual’s first language.

- Choosing locations for clinics that are convenient for the population, including those using public transport, and using the full range of local community assets to concentrate delivery in areas of low uptake.

- Providing services for those who cannot travel to vaccination sites, such as housebound people and care home residents.

3.1.16 We have heard strong support for primary care’s role in delivering vaccinations: general practice in particular for childhood immunisations and as the principal provider of infant vaccinations such as MenB and rotavirus; and both general practice and community pharmacy as instrumental in the delivery of COVID-19 and flu vaccinations25. We also heard that, for many primary care providers, vaccination has become an important part of their overall sustainability. At the same time, however, data on uptake in different communities suggests that these delivery models do not have the same level of success everywhere.

Case study: Community school age immunisation service (CSAIS) provision of BCG and hepatitis B vaccinations in the East of England

Babies eligible for BCG and hepatitis B vaccines are those with family links to countries with high tuberculosis rates and those born to mothers with hepatitis B, respectively. These groups are more likely to be experiencing health inequalities, so ensuring that families can easily access these vaccinations is crucial.

To improve accessibility, the East of England Region Immunisations Team commissioned CSAIS to offer hepatitis B neonatal vaccinations from 2020 and BCG from September 2021. The CSAIS is based in community locations and offers flexible drop-in appointments. It also has access to CHIS data, meaning it can identify and offer vaccinations for siblings who may be missing immunisations.

By the end of March 2023, uptake of hepatitis B vaccines in eligible babies had doubled. As of April 2023, BCG uptake for babies aged 3 months (as part of a catch-up offer) is 73%, the second highest regional uptake in England and above the national average of 69%.

3.1.17 We therefore expect in future:

- Systems will want to continue to draw on primary care in the delivery of both life-course and seasonal vaccinations, given the benefits this brings.

- Systems will also want the ability to design their network to suit the diverse communities they serve, recognising that different provider types (including primary care, community services, secondary care and others) are best placed to reach different parts of local populations.

- Systems can enable community pharmacy to play a greater role in seasonal vaccination delivery where appropriate, including increased collaboration between community pharmacy and other parts of the vaccination delivery network. Preschool immunisations will continue to be commissioned from general practice across the country, tailored to the local population as described above and supplemented with additional services where necessary to improve uptake.

Case study: HPV vaccine catch up in the North East and North Cumbria

HPV vaccination consents were significantly lower than than in years before to the COVID pandemic. Therefore a service was needed to look at new innovative ways to tackle this. NHS England commissioned Northumbria Healthcare Trust’s School Age Immunisation Service to deliver all school age vaccinations across Northumberland, North Tyneside, and Newcastle upon Tyne.

In June 2022 a pilot was conducted in Newcastle upon Tyne where a small team of 14.5 WTE staff devised a communications programme to target unvaccinated individuals. This included a poster campaign with one QR code that would take families straight to our electronic consent page and another to take them through to the UKHSA health education publication. This was sent to all schools, 0-19 services and GP practices to enable a visible presence across the county. All schools had a named nurse who supported with information sharing and vaccination sessions. Utilising GDPR legislation, all schools were asked for their class lists with contact telephone numbers to ascertain pupils who had not submitted a consent form. The NHS No-Reply text messaging service was then used to target these families directly.

By the end of July 2022 an additional 1,569 young people were successfully vaccinated from this pilot. Subsequently this strategy was deployed in Northumberland and North Tyneside.

The NHS ambition to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040

Vaccination is essential to protect against the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is responsible for up to 99% of cervical cancers. We will soon develop further implementation plans for how HPV vaccinations, alongside cervical screening and pre-cancer treatment, can help achieve the NHS ambition to eliminate cervical cancer by 2040.

To support increased uptake of HPV vaccination, the first pillar of our plan, we will be making changes to some elements of school-aged vaccination delivery. This includes improving communication with parents and enabling them to easily consent for their child to be vaccinated, changing how providers of school-aged vaccinations capture data, and enabling better collaboration across the vaccination provider network about who has and has not been vaccinated. This will better allow providers to identify areas of low uptake and undertake targeted outreach. This may include offering opportunistic vaccination outside schools, delivering education and awareness sessions in convenient locations, and the development of tailored communications for underserved communities.

3.2 Targeted outreach services for underserved populations

3.2.1 Our experience of delivering vaccinations and our engagement with the public, patient groups and providers of vaccination services tells us, overwhelmingly, that some people and communities cannot be well served by a core service, even one designed to be as accessible as possible. To increase uptake both in those communities and overall, we will need to provide supplementary outreach services, designed to meet specific needs.

Understanding need

3.2.2 Local commissioners and providers of healthcare services, including local authorities and their directors of public health, are best placed to risk-stratify their populations and identify people and communities in their areas who require bespoke or targeted approaches – and to understand how to reach them through people, locations and services that are trusted by members of those communities (see below). These populations will often align with Core20PLUS5 populations. ICBs should therefore be responsible for planning outreach services to best meet the needs of their populations, in partnership with local government, screening and immunisation teams (SITs), local community groups and the voluntary sector.

3.2.3 Nationally, we will provide systems with digital tools that help them identify those who are unvaccinated or who need a catch-up offer. This is explored in section 4.4.

3.2.4 Outreach approaches will be needed most in areas of deprivation and ethnic and racial diversity, as well as for inclusion health groups.26 This means they will be needed in every system in the country but will be a much larger part of the total offer in some systems than others.

3.2.5 Outreach services should be planned alongside the core offer, as an integrated part of the system’s vaccination delivery network. This does not mean a single provider, single setting or single delivery model, but oversight and co-ordination across all vaccination services to ensure the whole population is reached and efficiencies are maximised. The Fuller Stocktake states outreach “should not be considered a bolt-on to the day job” – it must be delivered in a joined-up way with other services.27

3.2.6 The type of outreach services deployed will depend on the community being targeted and the local partnership opportunities available. Some outreach may need to be planned or delivered across multiple systems to maximise value for money. Potential types of outreach service include:

- walk-in services based in the community, offering a range of vaccinations for adults and children, including catch-up

- roving and pop-up services in trusted and/or convenient sites, such as community and faith centres, shopping centres and childcare settings

- collaborating with other local providers and voluntary organisations that are already embedded in underserved communities

- opportunistic vaccination, including in settings people visit for healthcare or other purposes, or when people receive services in their own homes.

3.2.7 Systems will need to consider the cost and impact of different interventions to inform local decisions on investment. We will continue to work nationally and regionally to support robust evaluation of the effectiveness of different outreach approaches and provide toolkits and expertise to help systems choose those that are most effective and best value for money for their population.

3.2.8 Within our digital changes, a key target will be to ensure timely and accurate data is available from GPs and other providers, to ensure a consistent view of uptake across all vaccination services. Visibility of this data at national, regional and local level will support planning of targeted outreach services, building on the approach for COVID-19 and flu.

Case study: Support for people with a learning disability in Liverpool

Following the first wave of the pandemic (February to June 2020), it was identified that people with a learning disability were a vulnerable group due to a higher risk of death from COVID-19 infection compared to the general population.

To better protect this group, Central Liverpool PCN provided a tailored COVID-19 vaccination service. This included the offer of extended appointments, which were staggered to avoid waiting and to ensure the waiting room remained quiet and calm. The PCN made the most of these vaccination appointments by providing annual health checks (AHCs) at the same time. These checks are vital for identifying and addressing health concerns in people with a learning disability, and many would have missed them during lockdowns.

The project was co-ordinated by the PCN Integrated Care Lead, and Learning Disability Clinical Champion, supported by general practice staff, community learning disability teams, patient care administrators, pharmacists, and University of Liverpool medical students. On the first full-day clinic, the team vaccinated 78 people with a learning disability (which equates to 31% of the PCN’s registered learning disability patients) and completed 30 AHCs. Feedback from patients and carers was positive, and learning from this service will be applied in future clinics for this patient group.

Case study: Catch-up vaccinations for refugee and asylum seekers

Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire ICB commissioned the Sirona migrant health and community vaccination teams to provide healthcare checks for refugees and asylum seekers living in local hotels, from numerous countries and places of danger including Afghanistan, Syria, Russia and Ukraine. Sirona is a social enterprise that provides community health services across the ICB.

The community vaccination team liaises with GPs and provides vaccinations at the hotels, which have over 1,000 residents. The migrant health team first supports migrants to register with a local GP practice, so that their vaccinations can be included in their primary care record. As refugees and asylum seekers are at risk of ill health due to fractured access to healthcare support, Sirona’s health team also offer health checks including blood tests and signposting to relevant health services, and provide volunteer translators through their links with local volunteer and community groups.

Between January and August 2023, 950 vaccines have been delivered, 657 of which were for diphtheria and 221 for first and second doses of MMR.

Reaching into communities

3.2.9 The most effective forms of outreach will be those based on collaboration with voluntary and community sector partners in the local area that have built trusted relationships with communities over time.

3.2.10 In most areas of the country, different sections of the population are accessing a range of community assets; for example, voluntary organisations that provide support to older people, parents or people with disabilities.

3.2.11 ICSs, including local authorities and their directors of public health, should consider how they can partner with these groups and organisations to build confidence in the vaccination event and support informed consent. The starting point for a discussion about vaccination is often not the vaccination itself, but other issues that matter to people such as employment or energy bills.

Case study: Reaching into communities in Norfolk and Waveney

In Norfolk and Waveney ICB, access to vaccination was identified as a barrier to increasing uptake in areas of deprivation and for inclusion health groups. To meet this identified need, a ‘Wellness on Wheels’ bus was set up in partnership between the system and Voluntary Norfolk – a local organisation supporting volunteers and voluntary organisations. Partnering was essential to increase engagement and trust with communities that have a historical mistrust of the NHS and other governmental organisations.

This bus provides an opportunity to reach into those communities that do not access health and care in more traditional ways or who are underserved by fixed delivery models. Sites have included local supermarkets, market events and other local community events.

Since the service was established in November 2021, over 600 COVID vaccines have been administered with almost 400 of these being administered in the last 6 weeks of the 2023-24 autumn/winter campaign. In addition, the delivery of services has now widened to encompass a broad range of prevention services including drug and alcohol, stop smoking, sexual health, NHS health checks, citizens advice, social prescribing, antenatal and parent support, and learning disability health check promotion.

3.2.12 In addition, ICSs will want to consider whether and how they can use community facilities to deliver vaccinations and maximise uptake in people who may be less likely to access mainstream healthcare services. While the circumstances of the NHS COVID-19 vaccination programme were unprecedented, it showed that using facilities and services that have familiar and trusted staff, established transport links and convenient access, can be highly effective and can inspire trust and confidence in the communities of which they are part. These facilities could include:

- local authority amenities such as libraries or leisure centres

- social clubs or sports grounds

- health or care settings

- family hubs especially for babies and children

- support services for issues such as housing

- places of worship.

Case study: Tackling vaccine hesitancy through cultural sensitivity in the Northwest

Blackburn with Darwen (BwD) CCG had the lowest flu vaccine uptake among 2–3-year olds in 2019/20 and 2020/21 across Lancashire and South Cumbria ICS. To increase these rates, the Northwest Region’s Public Health Commissioning Team worked with primary care teams to launch a tailored invitation initiative across three of the four PCNs in the CCG between November 2021 and January 2022.

Working with PCNs, the regional team developed a personalised invitation for the parents of all unvaccinated 2–3-year olds. This mentioned their child’s name and was signed by their local GP. The reverse of the invitations also included easy read images to support understanding of key messages. As BwD CCG had a large Muslim community (54,146 people identified as Muslim in the ONS Census 2021, the second most common religion in the area), the region commissioned qualitative insights work to better understand Muslim parents’ concerns regarding children’s vaccinations. This informed a Q&A in both English and Urdu that was shared alongside the letter, reassuring parents that an alternative flu vaccine could be provided that did not contain porcine gelatine.

By providing personalised invitations and a culturally sensitive Q&A, GP teams were able to build on their connections with local patients and their families. Among the three participating PCNs, 34.5% of the total flu vaccinations delivered to 2–3-year olds in the 2021/22 autumn season took place after the local letters were sent. This compares to 23% in the PCN that did not take part, suggesting these tailored invitations encouraged young families to come forward.

3.2.13 Communication should be based on up-to-date insight about individual community’s priorities and barriers to vaccination and should use professional and other trusted voices from different communities.

3.2.14 Local authorities play a lead role in planning and delivering outreach. This can include identifying underserved populations, undertaking engagement work that increases understanding of vaccination and supports informed consent using the principles of behavioural psychology to design services, and working alongside NHS providers to deliver vaccinations in the community.

3.2.15 Nationally, we will strengthen the partnerships built during the COVID-19 pandemic with stakeholder networks and communication channels serving communities of faith, and racial and ethnic minorities, for whom uptake is lower.

Case study: Childhood MMR vaccination clinics for Charedi Jewish community

North Hackney and Haringey London boroughs have high numbers of Charedi and Orthodox Jewish groups, with Stamford Hill having a Hasidic Jewish population of over 30,000. A high proportion of Charedi children under 5 in these boroughs receive their vaccines later than clinically advised, compared to the population as a whole.

In July 2023, Springfield Park Primary Care Network held vaccination and health clinics at the three GP practices with the highest proportion of Charedi patients. The PCN built on learnings from the polio booster campaign in September 2022, where it offered additional clinics at local practices for Charedi communities on Sundays after Shabbat (which runs from Friday evening to Saturday evening) and provided vaccinations at a Charedi and Orthodox Jewish children’s centre.

This was a multidisciplinary team effort, involving recallers, nurses, practice managers and volunteers, with funding support from Northeast London ICB. Leaflets promoting the July health clinics with quotes from local rabbis on the importance of getting MMR jabs were placed in the local Charedi press, community organisations and children’s centres.

By working with Jewish faith leaders, local press and community services, services were tailored to best suit Charedi and Orthodox Jewish communities. Over two Sunday clinics, more than 100 children were vaccinated. The PCN continued to run some clinics over the summer, prioritising vaccinations before the Jewish holidays.

3.3 Integrated teams who put vaccination at the heart of prevention and wellbeing

3.3.1 Vaccination is a public health opportunity. Integrating the delivery of vaccinations with wider person-centred healthcare services, planned and delivered by neighbourhood teams, can help make the most of the vaccination event.

3.3.2 Aligning vaccinations with other healthcare interventions can be particularly effective in communities that experience health inequalities and can help those communities access a wider range of services to improve their health and wellbeing.

Integrated neighbourhood teams

3.3.3 The Fuller stocktake proposed that PCNs evolve into integrated, multidisciplinary teams, delivering to communities at home, neighbourhood, place and system level28. We believe that vaccination across the life course should be at the heart of these teams, as an integral part of a cradle-to-grave prevention approach based on population health need.

3.3.4 An integrated team should be adaptable and work across the vaccination delivery network. It should flex according to type of vaccination and of provision, including to deliver much of the bespoke outreach described in section 3.2. When not vaccinating, the team should be capable of delivering other healthcare interventions. Vaccination activity could be profiled across the year to maximise these opportunities and support retention.

3.3.5 The way teams are configured will look different in each system. Paragraph 4.3.4 sets out some of the skill mix considerations for the commissioned vaccination services element of integrated neighbourhood teams and deployment of appropriate legal mechanisms for delivery.

Case study: Luton Wellbeing Hub

Life expectancy in Luton differs by 8 years between those living in the most deprived areas and those in affluent communities. To address this inequality, in November 2021 NHS Bedfordshire, Luton and Milton Keynes ICB set up a partnership with Luton Council and Hertfordshire Community Trust (CSAIS and adult services) to establish the Luton Wellbeing Hub in an easily accessible central shopping centre.

This collaboration with local partners means a range of key health support and vaccinations can be delivered on one site to people from deprived communities – from MMR and COVID-19 vaccinations, alongside health checks for conditions associated with shortened life expectancy (eg checking BMI and blood pressure, smoking cessation advice), to drop-in support sessions with the Citizens Advice Bureau. Close connections were developed with local PCNs and the Local Medical Committee, to ensure that the hub operated in collaboration with GP services.

Between May and September 2022, over 10,000 COVID-19 vaccines and 807 children’s vaccines were delivered.

Case study: Integrated neighbourhood teams at Healthy Hyde PCN

Healthy Hyde PCN in Greater Manchester employs 50 people across many different disciplines (including health and wellbeing coaches, complex care nurses, paramedics and pharmacists). The PCN covers 77,000 people, over 60% of whom live in the top two most deprived deciles of postcodes in England.

Healthy Hyde works beyond PCN borders, collaborating with local voluntary organisations, statutory bodies and community services to provide integrated, holistic care for its local population at neighbourhood level. A key element of this care is vaccinations that are provided through a number of services. This includes vaccination information sessions held at PCN-led English lessons for asylum seekers and refugees who can experience barriers in accessing health services. A complex care nurse attended these sessions with a translator. Over three sessions between October and December 2022, nearly 70 COVID-19 vaccines were delivered.

Healthy Hyde also runs PCN-led delivery of care home vaccinations, employing complex care nurses, care co-ordinators and pharmacists. This approach has simplified vaccinations for care homes, as they can directly contact the PCN team rather than individual GP practices. Between September 2022 and February 2023, 674 flu and COVID-19 vaccines were delivered across 14 care homes.

Integration with wider prevention activity

3.3.6 Systems should structure delivery of vaccination, via the neighbourhood team, to maximise uptake of other preventative services as well as vaccination uptake. Communities with low uptake of preventative services often find it more difficult to access services and have fewer interactions with services; providing them with a single contact for these services can help. Baby and pre-school vaccinations, for example, are a good opportunity to assess overall child and parental health and any safeguarding issues. Even efficient and high-volume vaccination delivery settings should be able to offer this or refer to structured local services.

3.3.7 Systems should determine the right interventions to meet local population need while maintaining the effectiveness of the vaccination service. They should:

- Prioritise hypertension case finding, smoking cessation in adults and asthma checks in children and young people.

- Use population health data and public health intelligence, including from their director of public health, to understand the key health and social characteristics of their communities, deploying interventions that will benefit those communities, improve population health outcomes and reduce healthcare inequalities.

- Draw on the proven high impact interventions for adults and children to improve overall population outcomes by making every contact count (MECC)29.

Integration with clinical pathways

3.3.8 We propose greater joint working across all local service providers, including acute, community, mental health and local authorities, to integrate vaccination into existing clinical pathways for groups with particular needs. Systems should consider how they can:

- Make vaccination the business of everyone working in patient-facing settings, through training and awareness campaigns. If a practice nurse is testing a patient’s blood pressure, a midwife or other member of the clinical team is supporting a pregnant or postnatal woman and their child or a community podiatrist is carrying out a diabetic foot check, for example, they could be enabled to talk to the person about relevant vaccinations, answer questions and, if they cannot deliver the vaccination there and then, signpost to the appropriate services.30

- Base vaccinators in healthcare settings accessed by people who may benefit most from vaccination. This may include emergency departments, outpatient departments, family hubs and community diagnostic centres. Family hubs may be especially beneficial for babies and children where parents may be less likely to access a standard offer.

- Train and deploy a wider set of professionals to deliver vaccinations. Local authority services for 0–5-year olds, for example, have unparalleled contact with underserved communities. Health visiting teams as well as school nursing teams have successfully delivered vaccinations in the past and continue to do so in parts of the country, making use of their extensive skills and relationships. Any such arrangements would need to be locally planned and take into account workforce capacity and funding requirements.

3.3.9 Achieving the integration outlined above will require data systems that give access to an individual’s vaccination history (see section 4.4) and flexible vaccine supply chains (see section 4.5), and may require additional training.

Case study: Nurse-led vaccination role at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

In autumn 2022, Alder Hey Children’s Hospital introduced a dedicated outpatient nurse vaccinator role to provide vaccines for staff and patients, including in the inpatient areas. Alder Hey flexibly used some of its flu funding resource to employ the nurse vaccinator for 6 months; they also offered catch-up immunisations for children during outpatient appointments.

An infectious disease nurse identified eligible inpatients who were missing their vaccines and worked with clinical teams to prioritise and offer vaccinations. The outpatient nurse vaccinator flexibly supported vaccinations on hospital wards, providing flu and wider immunisations.

Alder Hey has emphasised the importance of vaccination across its services, ensuring that everyone in its patient settings makes it their business to vaccinate. For example, as staff noticed that mothers would often ask to have a COVID-19 vaccine once they saw their children getting theirs, Alder Hey established a pop-up family clinic on site. This operated most weekends and on certain weekdays from April to July 2022, providing a total of 467 child and 254 adult vaccinations. Alder Hey has also provided specific services for children with special access needs, such as those with a learning disability, autism and wheelchair users.

Providing embedded vaccination services in Alder Hey’s outpatient department and across wards enabled nursing staff to make the most of contacts with patients and families.

4. How we will collaboratively deliver

4.1 Strong system leadership

Local responsibility and flexibility

4.1.1 ICBs should have increased responsibility to commission a vaccination delivery network (covering life-course, seasonal and outbreak), that is tailored to the needs of their population and the local provider market, and meets a set of high-level outcomes and standards.

4.1.2 Integrated care partnerships (ICPs) should consider the vaccination strategy for their ICS. Vaccination should be included in the ICP’s integrated care strategy and be part of their system-wide health protection approach, building on evidence from the local joint strategic needs assessments (JSNA). ICBs should take responsibility for delivery, including vaccination in the joint forward plans and working closely with local authority partners to ensure every eligible person in the area receives a meaningful vaccination offer. In some areas the ICB may need to work with neighbouring systems to ensure consistency or deal with cross-border issues. ICBs should have a named executive director responsible for vaccination to maintain and support the assurance responsibility of all directors of public health within local arrangements, in line with NICE guidance (NG218).31

4.1.3 To enable this, we intend to delegate responsibility for commissioning NHS vaccination services to ICBs, subject to an assessment of readiness and final approval by ministers. We will work with ICBs and other stakeholders to determine an appropriate roadmap for this, including consideration of any functions that may be retained nationally or regionally. ICBs will want to reflect this roadmap in their five-year joint forward plans.