Equality and health inequalities statement

This operational guidance sets out the principles that should underpin the planning, design and delivery of an autism assessment pathway that works for everyone irrespective of where they live, their background, age, ethnicity, sex, gender, sexuality, disability, or health conditions. Implementation of this operational guidance will include taking actions to reduce known sources of health inequality that exist in access to, or experiences of, an autism assessment across England.

Overview

This operational guidance sits alongside the national framework to deliver improved outcomes in all-age autism assessment pathways. It provides an overview of common roles and responsibilities that autism assessment services have. These include conducting autism assessments, as well as providing training, consultation and liaison, and supervision, to a range of local and regional services and organisations.

Part 1 of this operational guidance outlines key components of the autism assessment pathway. These are underpinned by ten key principles that should guide decision making about the design, procurement, delivery and evaluation of all services that comprise the autism assessment offer within the area, notably that this is:

- ethical

- evidence based

- respectful

- delivered by an appropriately skilled multidisciplinary workforce

- a comprehensive, coherent offer

- accessible to everyone

- co-designed by clinicians and people who access the services

- based on shared and current conceptualisation of autism

- transparent

- described in, and informed by, national statistical data.

Part 2 of this operational guidance outlines considerations for conducting autism assessments that differ from standard service delivery, such as using telehealth or seeing people who are in hospital or a forensic setting.

Part 3 focuses on the provision of autism-relevant training, consultation and liaison, and supervision.

For more information about the design, procurement, delivery and evaluation of accessible and effective autism assessment services, please refer to the national framework, which should be read in conjunction with this operational guidance. The national framework document outlines a brief overview of the most relevant policy context, general principles underpinning autism assessment service and how to apply these principles when commissioning.

Part 1.The autism assessment pathway

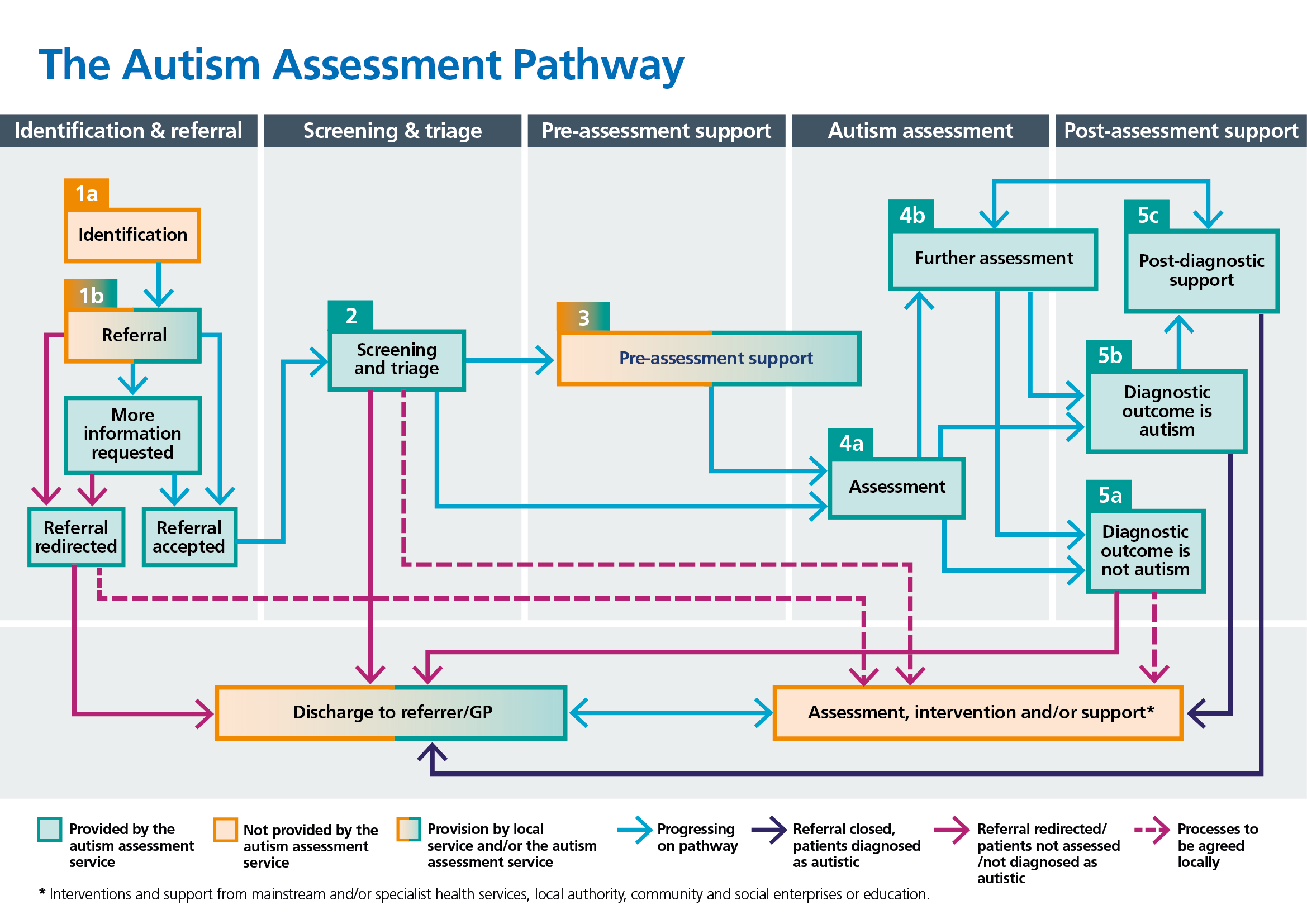

Five stages of the autism assessment pathway

People and their family/carers seek an autism assessment for a range of reasons. Confirmation of an autism diagnosis can be a validating experience (1–3) and facilitate access to services and support (4). Establishing if a person is not autistic is also important as it offers the opportunity for them to be referred into an alternative pathway, receive signposting to support or be directed to social prescribing link workers, depending on need.

Autism assessments routinely take place in different services, including child development centres, neurodevelopmental assessment teams and autism assessment services. In this guideline, and based on extensive stakeholder engagement, the autism assessment pathway (that is, from the point at which possible traits are identified and a referral for an autism assessment is first considered, through to discharge after an assessment has taken place) is seen to comprise five distinct stages, specifically:

- identification and referral

- screening and triage

- pre-assessment support

- autism assessment

- post-assessment support

Some services solely provide an autism assessment (stages 1, 2 and 4), whereas other services also provide pre- and post-assessment support (stages 1 to 5). For many people, sequential delivery of each stage of the autism assessment pathway is ideal. This recognises that people and their family/carers can benefit from signposting and support before and after the autism assessment, rather than simply focusing on the assessment element of the pathway (3,5–7). At the same time, there should be flexibility in service provision. For example, it is important to consider the needs, preferences and other time or work commitments of people, as well as their family/carers, a proportion of whom may themselves be autistic.

Importantly, the autism assessment pathway should be viewed in the context of other services (including health, social care and education) that a person or their family/carers may be receiving or could benefit from. This is because referral for an autism assessment does not preclude input from other services if there are identified needs that warrant support.

The five stages of the autism assessment pathway are outlined in Figure 1. It is recommended that a range of stakeholders in each Integrated Care System (ICS) and Integrated Care Board (ICB) collaboratively develop accessible autism assessment services for people of all ages and all abilities residing in that area. See Appendix B for a list of suggested stakeholders.

Reach, acceptability and effectiveness of these pathways should be evaluated periodically, including through service evaluation, audit or research, as well as feedback, concerns or complaints received. This should involve particular focus on any gaps in provision, such as for people who are approaching transitions (for example, from children and young people’s services to adult services), and people who are members of marginalised groups, have atypical presentations, and people with additional needs (for example, an intellectual disability, or visual or hearing impairment). Consideration should also be given to gaps between different services, including adult mental health and learning disability services, to ensure that people do not fall between service eligibility criteria.

Personalisation

There may be opportunities to use personalised approaches throughout the autism assessment pathway. More information on the comprehensive model for universal personalised care can be found in the national framework and on the NHS England website.

Two elements of universal personalised care may be especially relevant to the autism assessment process. Firstly, social prescribing link workers can offer signposting to local services and support networks when someone is early in the pathway and may provide continuity of care throughout a person’s journey on the assessment pathway, including when onward referrals are made. It is important link workers are appropriately skilled and trained to best support autistic and possibly autistic people (8). Social prescribing link workers form part of local personalised care offers across ICBs.

Secondly, decision making can be used to ensure that the person understands the risks, benefits and possible consequences of different care and support options. NICE has developed a shared decision making learning package to support healthcare professionals develop skills and knowledge to apply the clinical guideline on shared decision making (9).

Consent

In places throughout this document, we refer to the person’s consent, for example to taking part in the assessment, or to involving others in that process or sharing information that would otherwise be confidential. That consent is essential if they have capacity to make those decisions (as should be presumed if they are over 16, unless established otherwise, per the Mental Capacity Act 2005), or if they are under 16 years but are “Gillick competent” (that is, they have sufficient maturity and understanding to make those decisions). Where the person is a child who does not yet have Gillick competence to make those decisions for themselves, the decision may be made by the exercise of parental responsibility, where this is in the best interests of the child.

For someone over 16 who lacks capacity for the relevant decisions, the decision must be made in the person’s best interests, per the Mental Capacity Act.

Stage 1: Identification and referral

The first stage of the autism assessment pathway involves identification of potential autistic traits and subsequent referral for an assessment. While autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood onset, the possibility that a person is autistic can become evident at any age. It may be that people self-identify traits they associate with autism, or these may be observed by family/carers, professionals, friends or colleagues (6,7,10–13). A formal referral for an autism assessment may be sought when traits are first identified or when there are concerns about the impact these appear to have. Importantly, perceived stigma around an autism diagnosis or cultural stigma may present concerns to people or their family/carers, potentially serving to delay obtaining a referral (14–17). Cultural factors such as differences in knowledge, awareness and descriptions of autism may also contribute to delays (18–20).

Services can minimise the impact of these factors by ensuring referrers have up to date information that is clear and accessible to inform discussion with people and their family/carers, such as regarding the options for accessing an autism assessment within the area and what this may involve. While the latter screening and triage stage is a fact-finding process (stage 2), initial conversations with a referrer can also focus on preparing the person and their family/carers about possible outcomes of a referral and an autism assessment. Information should be tailored to the needs of different groups, including people of all ages, some of whom may have a possible or confirmed intellectual disability.

Identification

There can be a significant lag between the identification of possible autistic traits, a referral being made, and the autism assessment taking place (5,7). This is partly because some people and their family/carers experience barriers and bottlenecks at this early stage of the autism assessment pathway (21,22). See Appendix C for examples of barriers. This can result in a delay in people and their family/carers obtaining the right support when they need it. Consequently, routes into the autism assessment pathway need to be transparent and easy to access, irrespective of age or ability.

Facilitating sensitive conversations about a possible autism assessment

Discussions with professionals involved in a person’s care and support, for example, a GP or teacher, are often the first step in the process for requesting a referral for an autism assessment (23). Some people feel comfortable talking about why they would like to have this, but others may not. It may be difficult for them to articulate their thoughts, or they may find the professionals they approach dismissive and unsupportive (12,15).

Therefore, initial conversations with people and their family/carers should be conducted sensitively and with compassion (15), focusing on aspects including:

- Ensuring they have time to talk about possible autistic traits that have been identified and potential impact on day-to-day functioning. Offering a longer appointment than usual or follow up meetings may be appropriate.

- Broadly clarifying the range of difficulties or needs the person experiences – and the order of priority – to establish whether an autism assessment or referral for another type of assessment is necessary (for example, of mental health or intellectual ability). This can include clarifying if the priority areas of need or difficulties identified are the same for the person and their family/carers, or distinct.

- Identifying the drivers for, potential advantages with and any concerns about having an autism assessment.

- Considering any cultural differences that may make it difficult for some people and their family/carers to seek or accept a referral, such as perceived stigma about autism specifically or healthcare use more generally.

- Noting any contextual factors that may influence a referral being made (for example, for people and their family/carers who are from travelling communities or who have no current fixed abode).

- Making a plan to address needs and risks in the short term, if necessary.

The outcome of these initial discussions should be formally noted in the clinical records, including whether the person would like to proceed with a referral. This can help with continuity of care, for example if the person discusses this with a different clinician at a follow up appointment.

Referral

Some people and their family/carers report that information about the autism assessment pathway is inaccessible (6). There can be a lack of clarity about who can make a referral, when, how, and what will happen next. Understandably, this can be distressing for people and their family/carers and contributes to delay in obtaining support.

For each ICS, the following information should be publicly available and proactively shared across multiple locations, for example, social media and local authority publications, as well as all service provider websites:

- Accurate and up-to-date information about the autism assessment offer in each area, including details for services providing autism assessments (including name, address, contact details, general remit, eligibility criteria, referral process and documentation).

- An indication of waiting times for an autism assessment at each service.

- Information on Legal Rights to Choice of provider and team, and information to facilitate informed choice including waiting times, quality of assessment that would facilitate access to local services and any known limitations as a result of accessing an external pathway.

Suggested actions for the ICB:

- Check that people of all ages can access an autism assessment in the area.

- Address gaps in autism assessment provision for particular groups (for example, people with an intellectual disability, or people in inpatient NHS or independent hospitals or services, at residential schools and colleges, or in prison).

- Decide at an ICS level whether standardised referral processes across services have merit (for example, single point of access, an online form, shared templates).

- Develop protocols for how people and their family/carers can access pre- and post-assessment support if seen for an autism assessment by an external provider, including independent providers.

- Indicate what types of autism-relevant training is available for professionals working across services in the ICS.

- Identify who holds responsibility for periodically evaluating that information listed remains up to date.

A transparent referral process

People and family/carers report they would like to know more about the potential reasons for choosing to proceed with an autism assessment (or not), the process for referral, which services can provide this, and any differences in this according to age or ability. They want to know what the main components of the autism assessment pathway are and what they can expect as potential outcomes (7,24). From the outset, conversations about expectations are essential to encourage the person and their family/carers to approach the process as an assessment for autism, rather than anticipating a specific assessment outcome. At the point of referral, people should be made aware of their rights to choose a provider and provided with accurate and up-to-date information to inform these choices. This may include average wait time and where opportunities to access local pre- and post- assessment support after an assessment differs by service.

Autism assessment services have responsibility for providing referrers, people and family/carers with accurate and detailed information about the autism assessment pathway; ideally, this information is co-produced. This should be available in multiple formats. This can include leaflets (for example, placed at GP practices, mental health and learning disability services, and in education settings as part of the Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) agenda), and on the internet (for example, websites for health and social care services, and parent groups such as Parent Carer Forums). This should also be tailored for different audiences, including young people, adults and family/carers. Translation into other languages may be appropriate for people who use English as a second language. Similarly, easy read versions and plain English versions can be more accessible for some. Referral processes should be accessible, with services addressing possible barriers, including literacy levels and access to technology.

Developing easier routes into the autism assessment pathway

Referral routes for an autism assessment can vary according to the person’s age and availability of services. In some areas, the GP can refer directly to autism assessment services. However, there can be stipulations about what assessments or input are needed after possible autistic traits have been identified, but before a formal referral for an autism assessment is made. For example, people may first need to be seen for a more general assessment of difficulties, functioning or mental health, such as by a clinician in secondary care. Alternatively, people or family/carers may be asked to complete autism screening questionnaires, the scores of which may be used to help determine whether onward referral is deemed appropriate.

People and their family/carers may experience stress or distress in learning how to navigate these processes. While some areas may adopt an ‘all age, no wrong door’ referral system, good practice would be for each ICB area to have one accessible source of information about autism assessment services for all ages and the routes to these.

Additionally, it is sometimes suggested that family/carers of children and young people attend classes or courses focused on training in parenting skills while waiting for an autism assessment. This can delay input for children and young people. The research evidence for training in parenting skills in this context is limited (25,26), and the potential harm to family/carers by recommending they attend these courses is rarely considered (27).

There is some evidence for the success of parent mediated interventions (that may be delivered in a course format) targeting communication skills in young children, with improvements found in parent/carer and child interaction (28). Recommending interventions is appropriate only if clinically indicated. It should be based on the need for support, and not tied to the autism assessment pathway. However, parents should not be excluded from receiving support on the basis that their child is waiting for an autism assessment if they could derive benefit from this.

Taken together, decisions to delay referral for an autism assessment must be underpinned by a clinical rationale.

Making a referral for an autism assessment

Referrals for an autism assessment are usually made by professionals working in health services, social care and in education, or by professionals in the criminal justice system. Table 1 shows a summary of these settings and the roles of professionals who commonly instigate referrals. Some areas also accept self-referrals or referrals from family/carers.

Table 1. Examples of professionals who may make referrals for autism assessments, and the setting in which they may work.

| Setting | Professional |

| Health | GPs Paediatricians Psychiatrists Nurses Clinical, counselling or forensic psychologists Occupational therapists Speech and language therapists Health visitors |

| Social care | Social workers Occupational therapists Speech and language therapists |

| Education | Educational psychologists Speech and language therapists Special Educational Needs Co-ordinators Teachers at schools or colleges Nursery teachers |

| Criminal justice | Probation officers Professionals working in court Forensic psychologists |

A joint referral from two or more professionals who know the person enhances the specificity of this. For example, this could be contributed to by the GP and either the Special Educational Needs Co-ordinator (SENCo) or the clinical psychologist offering intervention at that time. When joint referrals are made, clarity is needed about which professional and service has primary responsibility for the person while they are on the waiting list for an autism assessment, and for actioning onward referrals and recommendations.

Self-referrals for an autism assessment, and direct referrals from family/carers, are less common in NHS services. If autism assessment services accept these, there must be operational protocols about what information is needed so that appropriateness (that is, eligibility for the service) can be clinically evaluated. There also needs to be an agreement that the person’s GP be kept informed about the referral and outcome to ensure continuity of care. Careful consideration must be given to factors such as which professional and service has responsibility for ongoing risk management and can initiate further referrals if indicated at subsequent stages of the autism assessment pathway. If the person is formally referred by a professional, for example, they may be more easily signposted to other services during and after the autism assessment.

Preparing a detailed referral letter

Some autism assessment services require a general referral letter while others have a standardised referral form. The latter can reduce duplication and effort on the part of people and their family/carers. Submission of referrals via an online portal can be particularly efficient.

Referrals should be comprehensive and, at the very least, summarise:

- Past and current clinical information (including about possible autistic traits and any other physical or mental health-related symptoms).

- Concerns, as described by the person and family/carers, and order of priority, whether these differ between the person and their family/carers, and how these concerns are currently being managed.

- Contextual factors (such as about who the person lives with, any dependents, their day-to-day activities).

- If known, information about adverse childhood experiences.

- Identified risks to or from self/others, including a risk management plan.

- Any requirements for adapting the autism assessment pathway if known (for example, as the person has an intellectual disability).

A referral should indicate whether the person has been referred for assessment for another developmental condition, including Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or possible intellectual disability. See Appendix D for a summary of suggested focal points for inclusion in an autism assessment referral.

The more detailed a referral is, the more informed the decision making can be regarding eligibility for an autism assessment and any adaptations the person or family/carers may benefit from along the autism assessment pathway. This can reduce inefficiencies at this initial stage, such as undue administrative and clinical time addressing inappropriate referrals and retrieving missing information. However, it is important that referrals are not declined based on omitted information that is not crucial for the referral, as this can cause unnecessary delay and frustration.

Information that may be relevant to include in a referral for children and young people:

- Clarity about whether the child or young person met developmental milestones at the expected age or whether there were any noted delays.

- Details about the education settings the child or young person attends and the current year or stage of education that they are in or specifying if they are not currently in education settings.

- A copy of the current Education, Health and Care Plan, plans put in place at SEN Support, or details of other access requirements at education settings, or other services if the child or young person is not in education.

- Whether the child or young person is due to move education settings within the following calendar year.

- A summary of concerns raised by teachers, along with examples of strengths and difficulties observed within the classroom and less structured education settings contexts (for example, break times, after school clubs).

- Details of any assessments conducted by professionals such as an educational psychologist, a speech and language therapist, an occupational therapist.

- An overview of any additional support the child or young person has or is receiving (for example, one to one support in lessons, referral for additional classes), including details of teachers and SENCo to input into the process and as points of contact post-assessment.

- If any siblings or parents have been diagnosed with a developmental condition or are awaiting an autism assessment.

- Whether the child or young person has some understanding of autism and the purpose of the assessment.

Information that may be relevant to include in a referral for adults:

- Age on leaving education.

- Any notable difficulties in education (for example, dropping out of education settings or university).

- A summary of the person’s independent living skills or requirement for social care or support.

- Any noted concerns in the context of employment (for example, a history of difficulties within the workplace).

- A description of the person’s current social circumstances.

- The person’s expectations of the autism assessment.

- Information about who is able to provide additional information, such as a parent or partner.

Information that may be relevant to include in a referral for people approaching transition:

- The age at which people are discharged from the service they may be referred to.

- If and how referrals can be transferred from services for children and young people to an adult service, without the person being placed at the bottom of the waiting list (that is, they should not wait disproportionately longer if their referral is transferred to an adult service).

- If and how referrals can be transferred to a service in another area if the young person moves from the family home for university.

- Which service will keep the person and their family/carers updated about the potential transfer of a referral to adult services.

Stage 2: Screening and triage

Streamlined and accessible referral processes help to ensure that the second stage of the autism assessment pathway – screening and triage – is efficient and effective at identifying people who are eligible for the service and will potentially benefit from an autism assessment. This process should also identify what components will be included in the assessment (such as via a differentiated pathway). Equally, timely decisions about people who are not eligible or are more likely to benefit from assessment by another service is essential for facilitating onward referral or signposting to another service.

Different services use the terms screening and triage interchangeably, or to refer to distinct aspects of the autism assessment pathway. Some services use these steps to determine eligibility for an autism assessment. This means some people may not be offered input beyond triage if this does not appear to be clinically indicated.

Each autism assessment service should, therefore, define screening and triage processes as per commissioning agreements (for example, what the service is commissioned to provide, for whom, in what circumstances and with any additional requirements noted, such as for children and young people approaching transition age). Additionally, there should be clarity about when screening and triage take place (for example, the number of days from the point of receipt of a referral), and the range of potential outcomes from these processes. This information should be available for people and family/carers.

Screening

Screening processes require input from administrative staff and clinicians. On receipt, referrals are usually reviewed in the first instance by administrative staff against pre-agreed eligibility criteria for the service, such as the age of the person and whether they live in the relevant catchment area, unless the referral has been made through Patient Choice. The sensitivity and specificity of these criteria or checklists should be evaluated periodically, for example, in relation to conversion rates (the proportion of people diagnosed with autism relative to the total number of people seen for an autism assessment). The criteria should also be reviewed if commissioning arrangements for the service change, or if there are changes to eligibility criteria for other autism assessment services in the area that may impact on the flow of referrals elsewhere.

Screening necessitates clinical input to determine if an autism assessment is appropriate based on the referral letter/form, with or without additional information being obtained in the interim. The focus here is on ascertaining whether the person may have traits indicative of autism, which is why comprehensive and detailed information is required.

A further aspect of screening involves noting any reasons why the referral cannot be accepted, for example because the person does not meet the age criteria for the service. Alternatively, a person may have specific additional diagnoses or difficulties that are outside the remit of the autism assessment service. Decisions to decline a referral are ordinarily made by senior clinicians responsible for screening these or the multidisciplinary team (MDT). In either instance, the referral should be promptly returned to the referrer or forwarded on to a more appropriate service if this is possible (depending on relevant service level agreements).

Some areas may have comparable processes for reviewing referrals across children, young people and adult services. This can make it simpler and more efficient for referrals to be passed on, such as in the instance a person is referred for an autism assessment during the transition period from children and young people to adult services.

In some instances, screening can take substantial time. For example, if the referral lacks information required to make a decision about appropriateness for the service, or when there is evidence of clinical complexity. Autism assessment services may choose to conduct audits periodically on the amount of time and input required at this stage, and by whom (for example, by administrative staff and clinicians), including the processing of clearly inappropriate referrals. Sharing information about the screening process with people in a commissioning role can highlight whether there are adequate resources available for this stage of the autism assessment pathway.

Triage

Triage helps autism assessment services to better understand a person’s presenting needs and difficulties, gather comprehensive information about possible autistic traits and traits suggestive of other conditions (for example, anxiety or ADHD), and potentially ascertain what the autism assessment should comprise.

Different approaches to triage

Triage can comprise one or more standardised or semi-structured methods, including:

- paper-based questionnaires or forms

- review of relevant correspondence (such as from health, social care, education, or the criminal justice system)

- meeting with the person, their family/carers, partners or friends

- liaising with professionals the person is in contact with or has recently been in contact with.

Any paper-based methods of triage should be accessible for people and family/carers, such as translated in other languages, easy read or Plain English versions if the service is an all-ability service, and age appropriate. Questionnaires, for example, are potentially easily completed online, but there should be options for people and family/carers to receive and return hard copies in the post if they prefer.

For more information about different types of triage, see Appendix E.

People and their family/carers may also be supported with triage in some areas by local authority, voluntary, community and social enterprises or education.

Clinical decision making after screening and triage

Information gathered by screening and triage processes should ideally be evaluated within ten working days. In some services, a senior or more experienced clinician who has reviewed paper-based information or met the person decides what the outcome of screening and triage is. Other services hold meetings – attended by the MDT – to discuss the information obtained and to form a consensus view about whether an autism assessment is indicated. Another option is for the decision-making approach to vary. For example, people who have more complexity or atypicality in presentation are discussed at dedicated MDT referrals/triage meetings and single clinicians reach a decision for people who appear, at triage, to present with less complexity.

Setting up an internal audit system, whereby clinicians discuss a proportion of decisions they have made with the MDT, their clinical supervisor or a peer can contribute to standardisation in practice. Additionally, a peer supervision process can be developed across autism assessment services within the area, to enhance parity in clinical decision making and provision.

The decision to progress to an autism assessment should be made based on the available information, while balancing the impact of any gaps. For example, there may be no one identified to complete an informant-based questionnaire about childhood or to support the autism assessment. However, this should not preclude the person having this if the available information suggests this is clinically indicated. Alternatively, a person may have a high score on an autism self-report screening questionnaire, yet in-person triage with an experienced or senior clinician, along with information from family/carers and clinical records, may indicate autism is highly unlikely. In this instance, it may be that the person is discharged without being seen for an autism assessment (that is, they are discharged back to the referrer as the information gathered until that point indicates they do not need an autism assessment). Conversely, differential or co-occurring diagnoses can obscure the (underlying) clinical presentation. Decisions to discharge people at this stage of the autism assessment pathway should therefore be discussed with the MDT and include appraisal of all the information available about the person.

Outcomes of screening and triage

A fundamental aim of screening and triage is to establish what the next clinical step is for the person, with regards to proceeding through the autism assessment pathway (that is, whether an autism assessment is indicated, at this time, with or without additional input or support from another service).

The most common outcomes following screening and triage are listed below.

- Discharge the person from the service if they are not considered to require an autism assessment. Signposting the person to other services may be appropriate.

- Recommend a ‘wait and see’ (or ‘watch and wait’) approach with the option of review or re-referral in the future. There should be an agreement about when this period will end, how the person can be seen for review (that is, will they need a re-referral or stay open to the autism assessment service) and who will provide a written summary of traits or difficulties for the referrer during this interim period. The person should maintain their place on the waiting list, so that they are not disadvantaged if there is a ‘watch and wait’ period.

- Recommend the person is offered assessment or intervention by another service to address acute symptoms or difficulties they present with that appear to take priority over an autism assessment (for example, psychotic symptoms or hypomania). Review by the autism assessment service (further screening or triage) takes place either after an agreed period or when symptoms or difficulties have been adequately addressed, to facilitate the person’s participation in the autism assessment. The person should maintain their place on the waiting list, so that they are not disadvantaged by the need for more urgent support by another service.

- Recommend the person is referred to a national specialist service for an autism assessment (for example, when the constellation or complexity of needs and difficulties warrants more specialist input).

- Offer the person an autism assessment without recommendations for interim input by another service. This may be tailored to their specific needs or difficulties and may also involve jointly conducting the assessment with clinicians based at another service, such as an ADHD or secondary care mental health service.

- Offer the person an autism assessment with recommendations for interim input by another service. Recommendations could include intervention for mental health symptoms (for example, low mood, anxiety), or ongoing assessment and support of special educational needs and disability within an education context. The autism assessment may be tailored to the person’s specific needs or difficulties. This may also involve jointly conducting the assessment with clinicians working at another service, such as an ADHD assessment or secondary care mental health service. Information about actioned recommendations should be shared with the autism assessment service while the person is on the waiting list.

Communicating screening and triage outcomes

A summary of the information gleaned at screening and triage should be communicated to people, their family/carers and professionals at different times, such as after this has been obtained or after the autism assessment has been completed. Services may adopt different approaches to this stage. Feedback can be summarised succinctly (for example, an overview of scores on self- and informant-report standardised questionnaires), or described comprehensively (for example, in depth description of responses to questions posed during an appointment with the person). All information should be presented in a manner and format that is accessible to the person, their family/carers and professionals.

The amount and detail of information shared at this stage also potentially depends on the outcome and next steps. Recommendations for interim or alternative assessment, or intervention by other services should be explicitly outlined, including clarification about what processes are already in place and which professional or service is being asked to make onward referrals or to assess the person.

Addressing concerns about screening and triage outcomes

Sometimes a person is discharged from the service without being seen for an autism assessment. They or their family/carers may feel disappointed about this outcome or concerned about how their perceived needs will be met. Similarly, professionals working in health, social care or in education may disagree with the clinical opinion. This means there should be an option for the person, their family/carers or professionals to discuss screening and triage outcomes. Discussion should include the rationale for how and why particular clinical conclusions have been reached (that is, what information was used to inform decision making), with emphasis on signposting to other services when feasible.

Expediting referrals

There are likely to be instances when people on the waiting list – whether already in receipt of support or not – are deemed to require an expedited (faster) assessment. Autism assessment services should outline the process for requesting an expedited assessment, criteria for reviewing these requests (such as an MDT discussion about new/current concerns) and the possible outcomes (for example, agreeing or declining the request). Criteria employed to support expediting of referrals may vary between services. Therefore, consistency and transparency are essential for ensuring parity in decision making. It may be that children and young people and adult services within the area develop shared criteria that are reviewed periodically.

Information that may be relevant when screening and triaging referrals for children and young people include:

- Using age-appropriate self-report questionnaires of autistic traits and traits of other conditions.

- Reviewing the My Personal Child Health Record and any medical correspondence from very early years.

- Asking for copies of reports from education settings, reports by educational psychologists, SENCOs and Education, Health, and Care Plans.

- Asking teachers to complete informant-rated screening questionnaires or to provide more general information.

- Establishing if there are other informants who can contribute information (for example, grandparents, childminders, nannies).

- Seeking information from support providers, for example if the person is a ‘Looked After Child’.

Information that may be relevant when screening and triaging referrals for adults include:

- Establishing if there are others who can contribute to the assessment as an informant for childhood and adult years (e.g., family, friends, partners) and the period during which they have been in contact.

- Obtaining information about further and higher education, such as end of year reports.

- Reviewing any correspondence relating to employment, such as occupational health reports.

Information that may be relevant when screening and triaging referrals for people approaching transition include:

- Seeking consent to share information gathered at a children and young person’s service with an adult service, rather than the person and family/carers needing to re-start the process.

- Determining what data sharing arrangements are in place if the person is moving to another area.

- Considering whether the person will need to complete additional screening questionnaires if they step up into an adult service.

Stage 3: Pre-assessment support

There is often a gap between screening and triage and the autism assessment taking place. This may be due to waiting times, preference, or clinical factors (for example, if the person is experiencing significant mental health symptoms) that warrant being addressed first. Pre-assessment support is described as important by people and their family/carers but has traditionally seldom been available.

Keeping people and their family/carers informed about their autism assessment pathway

People, and where consent allows, their family/carers and professionals they are in contact with should be updated about the estimated waiting time for the assessment regularly (for example, every three months). There should, however, be an opt out option for the person if they do not wish to receive these updates.

Updates should:

- Highlight the reason for the waiting time (for example, due to demand for the service or that the person requires prior assessment or intervention elsewhere).

- Indicate the approximate waiting time at that point.

- Provide contact details for a professional working at the service (for example, an administrator or clinician) who they can contact if they have questions while they are waiting, or if they need to advise about a change in circumstances (for example, a new home address or telephone number).

- Specify which service to contact if the person or family/carers become more acutely concerned about risk or acuity of presenting symptoms or difficulties.

- Confirm the next steps to be taken by the autism assessment service and how and when this will happen.

- Correspondence should be copied to the referrer so that they know when the autism assessment is likely to take place.

Providing resources for people and family/carers while they wait

Some people or their family/carers require support or input from health or social care services or education while the person is waiting for the autism assessment.

Needs identified can be related to possible autism (for example, social communication difficulties, problems with managing change and transition) or broader issues (for example, anxiety, disrupted sleep). Similarly, family/carers can benefit from signposting, advice or support at this time, in relation to supporting their child, other family members and in terms of their own wellbeing.

Needs and difficulties may have been highlighted in the initial referral letter/form or during screening and triage processes. For health-related needs, the referrer or local primary or secondary care services must not omit providing assessment or interventions relevant to the person’s needs while they are waiting for an autism assessment. Clarity about a possible autism diagnosis, in almost all instances, does not negate input for current needs, symptoms or difficulties that appear linked to physical or mental health. If a person’s needs are particularly complex, a link worker or equivalent can provide helpful oversight and coordination between services.

The autism assessment service may share resources or offer input while people are on the waiting list. This can include:

- Contact details for general local health and social care services, education support, voluntary, community and social enterprises, and social prescribing.

- Information about what will happen at the autism assessment and how, potential outcomes and a list of answers to frequently asked questions about the autism assessment pathway and process.

- General psychoeducational information about autism, such as what autism is and is not. This may include tips and strategies for addressing the possible impact of autistic traits.

- General psychoeducational information and evidence-based tips and strategies about symptoms and conditions commonly experienced by people referred for an autism assessment (including autistic and non-autistic people), such as low mood, general or specific anxiety, or disrupted sleep.

- General information and evidence-based tips and strategies for family/carers, such as around reducing stress and enhancing wellbeing.

- Peer support sessions or groups. Peer support sessions can include support from people or family/carers of people who have been through the autism assessment pathway.

- Information can be provided in written, audio-visual formats or via group approaches and should be accessible for people and their family/carers using the service (for example, translations, different versions for people with all abilities, and of different ages). Information should also be conveyed using an autism-informed approach (29), such as combining prose and images.

Education support – delivered outside of the autism assessment service

Some children and young people will benefit from support within an education setting while awaiting an autism assessment. Support for children in these settings should not be dependent on an autism diagnosis; education staff are expected to work collaboratively with external professionals and family/carers to ensure good quality support is in place when needed. Education settings are required to plan support in response to a child or young person’s individual profile of SEND through reasonable adjustments, SEND support or through an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP).

This should include how schools, while waiting for an assessment, can a) identify special educational needs linked to possible autism, and b) meet those needs. It could also include training and advice for schools, colleges and universities on the likely presentation of traits and needs of people while they are on the waiting list and how students can be supported.

Autism assessment services should provide information about a point of contact for queries while the person and family/carers are waiting, keep education settings informed of the anticipated waiting time for an assessment and signpost to other sources of advice and support when possible.

Informing professionals about pre-assessment support

Referrers and local services should be informed about any provision of resources or input to people while they are on the waiting list for an autism assessment. This may be via a template checklist or letter, or a more comprehensive letter for people or family/carers who have been offered more specific pre-assessment support.

Clinical records should be updated in a timely way, to reflect what resources or input has been offered to the person and their family/carers, when, and by which professionals. Scores on any outcome measures administered should also be provided.

Factors that may be relevant for pre-assessment support for children and young people include:

- Providing age-appropriate information for children and young people, and parallel information for family/carers.

- Considering the age and developmental stage mix of children and young people attending for group interventions.

- Providing clarity for family/carers about differences between parent-mediated interventions and training in parenting skills. Any interventions offered to family/carers should be delivered based on an emerging or robust evidence-base.

- Offering family/carers information about how to access support in education settings and in further or higher education.

- Signposting family/carers to social care support and options for breaks from caring.

- Undertaking stakeholder engagement to clarify what resources and sources of support for family/carers would like.

Factors that may be relevant for pre-assessment support for adults include:

- Providing information about access to support in higher education and at work.

- Putting together a list of links to different benefits and financial support options, with some supporting notes about completing application forms.

- Considering the age and life stage mix of adults attending for group interventions.

- Running group interventions at times people working full time will also be able to access.

- Giving examples of anonymised communication passports that adults may wish to edit for their own use.

- Undertaking stakeholder engagement to clarify what resources and sources of support family/carers would like.

Factors that may be relevant for pre-assessment support for people approaching transition include:

- Setting up protocols that outline which service (that is, the children and young people or adult service) will provide pre-assessment support if the young person is due to transition to adult services while awaiting an autism service.

- Providing information about adult services and adult-focused third sector organisations within the local area.

- Developing written resources, podcasts or blogs about cohesive transitions.

- Clarifying, for family/carers, the age at which young people transition to adult medical, mental health and neurodevelopmental services in the local area. For example, for some services this will be at aged 18, at others this may be at 21. Listing contact details for adult services commonly accessed by people seen by the autism assessment service.

- The GP becoming the coordinator of care from the age of 18 years, unless there are additional provisions available.

Stage 4: Autism assessment

Following screening and triage, people are either discharged from autism assessment services, offered a review appointment after a specified period to determine whether an assessment is clinically indicated (a ‘watch and wait’ approach) or placed on the waiting list for an autism assessment.

Clear aims for the autism assessment

An autism assessment has several aims. Broadly, these are to:

- Establish whether autistic traits are currently present, appear to have been lifelong and have contributed to impairment in different areas of daily life. For example, in education, occupation and social relationships (30).

- Screen for or assess common differential (that is, alternative) or co-occurring diagnoses.

- Understand the person’s strengths and goals, as well as their current needs and difficulties.

- Consider whether further medical, psychological, cognitive, sensory, skills-based or functional assessment is warranted and, if so, which service is best placed to provide this.

- Reach a clinical conclusion about whether the person is autistic and communicate this.

- Provide written recommendations to address current difficulties and needs, and to maximise well-being.

People, their family/carers and professionals should be aware of these aims prior to this stage in the autism assessment pathway – ideally at the point of referral, as well as in public-facing materials about the service (for example, documented in leaflets in written and diagrammatic form and on the organisation’s website). They should also know how information they provide will be used within correspondence (that is, in interim letters or an assessment report), if there will be opportunities to comment on the report before the final draft is shared with the referrer and other professionals involved, and what steps they can take if they do not agree with the assessment outcome or recommendations.

Additionally, the triage stage of the process may have provided the person and their family/carers with an opportunity to meet with clinicians and find out more about what the autism assessment could comprise.

The parameters of the assessment must be explicit, including which structured, semi-structured and unstructured measures may be used in the autism assessment (for example, autism assessment tools, or questionnaires), other neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions that will be screened for and assessed, and common outcomes from the assessment.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines (31–33) and Quality Standards (34) set out evidence for good practice in autism assessments. This includes which professionals may be involved and the recommended autism assessment tools and processes employed.

A multidisciplinary team approach to autism assessment

The workforce configuration of autism assessment services differs between settings. At a minimum, this should comprise an MDT, with substantial collective experience and expertise in assessing both autism and the range of neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions that can commonly be differential or co-occur with autism (33).

Owing to the nature of core training, paediatricians, psychiatrists and clinical psychologists are well placed to conduct autism assessments and reach diagnostic opinions, both independently, and as part of an MDT (22). Clinicians from other professional disciplines often undertake components of the assessment, but do not tend to routinely conduct these as sole practitioners.

Some clinical professionals may have additional training and qualifications to practise at multi-professional consultant or at multi-professional advanced clinical practice level to increase the number and diversity of professions represented in leadership roles. When these include training and assessed capability to conduct components of autism assessments, such as, for example, the autism credential, this may increase capability in relation to assessment components a professional can undertake. Some clinical professionals may have some additional non-clinical qualifications (for example diplomas, undergraduate or postgraduate degrees in research or other non-applied areas), this does not change their qualification to conduct each component of clinical autism assessment. Some components of assessment can be undertaken by staff under clinical supervision.

Given the possibility of clinical complexity and differential co-occurring diagnoses, it is not advisable for non-clinically trained professionals to conduct autism assessments independently (for example, research assistants, teachers), but they may make helpful contributions to aspects of the assessment or post-assessment support offered.

A differentiated approach to autism assessment based on clinical presentation and need

Based on information gathered from screening and triage, autism assessment planning should consider which components to include alongside the clinical interview. Planning should consider assessment tools, possible further assessments and which professional disciplines should be involved. The assessment can be differentiated in two main ways: standard or enhanced.

A standard autism assessment

- An assessment conducted by one or two clinicians (for example, a consultant psychiatrist and a mental health nurse or trainee psychologist).

- This may be indicated when information attained at screening and triage suggests an autism diagnosis is probable with no evidence of likely mental health considerations for the person. Furthermore, the circumstances may lend themselves to a straightforward process of gathering developmental and corroborative information. For example, the person is able to participate in the regular assessment format (including the clinical interview) and family/carers are available for interview.

- Consistent with NICE guidelines (31,32) the assessment should include, at a minimum, a clinical interview, behavioural observation, integration of developmental and corroborative information and consideration of possible differential and co-occurring diagnoses not identified at triage (especially when there has been a delay between initial referral, triage and main assessment).

An enhanced autism assessment

- An assessment conducted by two or more clinicians.

- This may be indicated when the screening and triage information suggests an autism diagnosis is possible but there is the possibility of other health considerations (for example, differential or co-occurring diagnoses). The circumstances may not lend themselves to a straightforward process of gathering developmental and corroborative information, such as parents being unavailable for interview or the person not being able to participate in the regular assessment format, such as the clinical interview.

- Consistent with NICE guidelines (31,32) assessment should include, at a minimum, a clinical interview, behavioural observation, integration of developmental and corroborative information, use of validated assessment tools, a broader assessment of clinical presentation (such as estimated intellectual functioning or sensory processing) and additional liaison with referrers and other involved service(s). Siblings, partners or friends may provide corroborative information.

Components of a good clinical assessment

The components of an autism assessment can vary according to the age and developmental stage of the person. As noted previously, the early indications from triage may direct the nature and breadth of the assessment, but not always. This means the autism assessment service should facilitate flexibility as needed, including having the option to incorporate additional components into the assessment, when clinically indicated.

The autism assessment must include a clinical interview with the person, conducted by a clinician with a medical background or a qualified mental health professional (for example, clinical psychologist or mental health nurse)(31,32). This is distinct from an assessment with family/carers or conversations with siblings (for example, developmental history taking or asking for descriptions of current concerns). This is also distinct from semi-structured behavioural observation assessments that specifically focus on traits associated with autism (for example, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – 2; ADOS-2 (35)). The clinical interview is pivotal for putting into context scores obtained on standardised questionnaires that may be used for screening or triage, or scores on semi-structured assessment tools. This also helps to address the question as to whether the person may have differential or co-occurring diagnoses; crucial for formulation and reaching clinical conclusions.

Themes for discussion at a clinical interview with the person include:

- Reason(s) for referral and the person’s, their family/carers and referrer’s expectations of the assessment

- the impact of past and current traits associated with autism (according to the International Classification of Diseases, eleventh edition; ICD-11 (30), or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition; DSM-5 (36)), and any modifiers for these

- current concerns, and the onset and trajectory of these

- developmental history

- information about what life was like growing up

- general day-to-day functioning

- education and occupation

- hobbies and passions

- needs and difficulties

- strengths, resilience factors and personal (coping) resources

- social circumstances, friendships and relationships

- physical and mental health and emotional wellbeing

- mental state assessment

- risk (to self/others including self-harm and suicidal ideation, and from others).

The assessment must include screening or assessment of common differential or co-occurring diagnoses, as part of the clinical interview conducted by a clinician with a medical background or a qualified mental health professional. This includes consideration of other neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD and intellectual disability, mental health conditions (including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder and related disorders, disordered eating, traumatic stress) and attachment-based difficulties.

The person and family/carers may also complete screening questionnaires about mental health and wellbeing. In this instance, responses should be followed up if clinically indicated. This is because it is important to ascertain whether low or high scores on questionnaires are consistent with information gathered during screening, triage and the autism assessment from the person. Information about other potential neurodevelopmental traits or mental health symptoms is crucial for developing a formulation and thereby the diagnostic opinion, as well as informing recommendations for post-assessment support or intervention.

Some services incorporate behavioural observation assessments (for example, the ADOS-2 (35)). These should be conducted by appropriately trained professionals, ideally with expertise in mental health and development. There must be clinical oversight if the professionals conducting these are not clinicians, and they should have regular supervision. These assessments may take place in clinic, at education settings or at home and can be structured, semi-structured or unstructured.

Importantly, behavioural observation assessments do not replace the need for a clinical interview. This is because scores cannot be meaningfully interpreted without the contextual information gathered during a clinical interview (scores below and above the indicative threshold suggested for autism may be due to the presence of autistic traits, differential diagnosis, or both autistic traits and co-occurring conditions).

Any deviations in the administration of standardised and licensed assessments (for example, conducting the ADOS-2 online) should be reported in the outcome documentation (for example, what adaptations were introduced, which, if any, activities or tasks were omitted or added), with clarity about how this may be relevant for any clinical conclusions reached.

Corroborative information is important for reaching clinical conclusions. This should be sought when feasible, and the person has consented to this. This may be obtained using a standardised semi-structured assessment (for example, the Autism Diagnostic Interview – Revised (ADI-R; 37)) or an unstructured interview. Some services gather this information as part of the triage process, whereas other services may do this as part of the autism assessment. It can be more challenging with older adults as parental information may not be readily available or may be less reliable owing to time passed since childhood.

As with behavioural observation assessments, interviews conducted with family/carers, such as the ADI-R, do not replace the need for a clinical interview that asks the person directly about their experiences growing up. Additionally, developmental information obtained in semi-structured assessments needs to be considered alongside all other information gathered, to discern whether scores below or above the threshold are attributable to the presence of autistic traits, differential diagnosis, or a combination of autistic traits and co-occurring conditions. Other information, such as from siblings, partners, close friends or professionals the person is in contact with, should be gathered when possible.

Development of service or area-wide templates for systematic gathering and recording of information can be useful for ensuring that key focal points for an autism assessment are addressed before or during Stage 4 of the autism assessment pathway. Using a consistent template for an area also makes it easier to transfer information, for example, if people have had a triage at a children and young people service, but are likely to transition to an adult service for the autism assessment.

Formulating a view about diagnosis

Clinical formulation of individual presentation, developmental patterns, strengths and needs, resources and difficulties, contributes to the clinical conclusions and provides the first step to generic and focused post-assessment support. Formulation is based on the integration of information gathered from a clinical interview, behavioural observation, developmental and corroborative accounts, clinical and educational records and liaison with other professionals. It must be viewed as more than just the scores on any given screening questionnaires or assessment tools.

At times, it may be necessary to consider all the information available and, on balance, to agree that the scores on standardised assessments do not present an accurate picture of the person. In other words, while specific assessment tools tapping traits associated with autism may yield scores above or below the indicative threshold suggested for autism, this remains a clinical decision – that is, made by clinicians on the basis of all available information and in light of their clinical experience.

Consensus diagnosis meetings provide opportunities to:

- present information gathered about a person.

- identify potential gaps in information before completing the assessment and determine how this can be best obtained.

- consider multidisciplinary perspectives about the formulation, including views about whether the person is autistic.

- outline recommendations to be shared with the person.

Communicating the assessment outcome clearly

The lead clinician or clinical team (depending on the protocol of the autism assessment service) shares the outcome with the person and their family/carers (as appropriate). Consideration needs to be given regarding the nature and format of this feedback to ensure this is accessible and clear, and that recipients can feel confident in the outcome, irrespective of what this is.

Some young people and adults participating in the assessment process may be expecting an autism diagnosis. Parents may be hoping for an autism diagnosis if they believe this is essential for securing necessary services to meet their child’s needs (38). Sharing the assessment outcome is never neutral, whether expected or not (3,6,11,13,39). A lengthy wait for assessments can make the outcome more important to people and their family/carers. If the standard protocol for the service includes sharing the outcome at the end of the main assessment appointment (usually involving a clinical interview), due time and attention should be given to this aspect of the process; this should not be rushed.

The following considerations are needed for the sharing the outcome of the autism assessment verbally:

- The person may benefit from more than one appointment to discuss this, whether diagnosed as autistic or not.

- Feedback may need to be offered face-to-face, even if the main assessment took place via a telehealth platform, particularly if the person or family/carers have difficulty understanding or accepting the outcome.

- Consider the skill set that clinicians require to share the formulation and assessment outcome.

- Feedback should be provided by a lead clinician or qualified clinician who participated in the assessment process and is known to the person and their family/carers.

- Local protocols for providing feedback can be developed in consultation with people and family/carers to ensure this is shared in a personalised manner.

- Check consent (from earlier consent processes) and current wishes for sharing the outcome with others, including the referrer or professionals in other contexts. (Consider that some information may be shared with GPs via local recording and reporting processes, such as System One, and the person and their family/carers should be made aware of this. See earlier section about consent.)

- Signpost people and their family/carers to information concerning their rights if an autism diagnosis is made, such as information to help someone understand how their diagnosis help them to seek reasonable adjustments in the workplace under the Equality Act 2010.

- Inform people and their family/carers that details of the assessment and the discussion will also be provided in writing.

The following considerations are needed for sharing the outcome of the autism assessment in written form:

- Develop local protocols for efficient and effective written communication of the assessment outcome and recommendations.

- Agree on integral components of each document. See Appendix G for the core components of an autism assessment report.

- Determine an optimal time within which to complete the autism assessment documentation and share with the person and their family/carers.

- Consider the option of a staged process of sharing the documentation (brief statement with headlines and evidence prepared within one week of the outcome, followed by a more detailed report including recommendations and next steps. Further documents might be provided at a later stage depending on the post-assessment support offered. (The function of the brief statement is to provide evidence of the diagnostic outcome and how this was reached. This also serves the purpose of a short statement that can be used by the person or family/carers for a wide range of purposes without the need to share the detailed clinical report that contains highly personal information.)

- Establish local systems to support the integration of clinical notes and electronic patient records to reduce duplication when producing outcome documentation.

- Where multiple authors contribute to the document, consider using shared documents to enable clinical professionals to work concurrently, rather than waiting for sections to be completed independently.

- When possible and sufficient administrative resources are available, consider dictation of letters and statements.

- Develop templates for assessment statements, reports and letters.

- Consider relevant recipients – documents may need to be available in the future so that a copy can be held by the person, family/carers or Primary Care, irrespective of who the referrer is.

- Consider privacy rules and sharing information, such as when reporting information about extended family members who are not part of the autism assessment process.

- Include, when appropriate, the comments and contributions of the person in the process, outcome and recommendations.

Recording assessment outcomes in clinical records

Clinicians are responsible for recording the assessment outcome in the clinical records system. This is essential for maintaining contemporaneous and accurate information about a person and ensures other health professionals in contact with them are aware of the diagnosis.

This is also an important step in the submission of regional recording and coding of the referrals for autism assessment, waiting times and assessment outcomes that are monitored nationally via the Mental Health Services Data Set (MHSDS) and Community Services Data Set (CSDS) respectively.

Specific considerations for conducting an autism assessment with children and young people can include:

- Offering flexibility around appointment times to accommodate days and times spent in education and family/carer commitments.

- Considering the age and developmental stage of the person and which semi-structured assessment measures are appropriate to their needs.

- Recognising that good practice for autism assessments in children and young people includes assessment/observation in at least two settings, such as clinic and education setting, irrespective of the service (child development centres or children and young people mental health services).

- Facilitating opportunities for parents/carers to speak with clinicians independently of the child or young person, if appropriate.

- Offering information about diagnosis in an accessible way for both children and young people and family/carers.

- Making recommendations about which service may be able to update the assessment report over time, to reflect any changes in strengths and needs.

Specific considerations for conducting an autism assessment with adults can include:

- Identifying whether there are informants who can take part in the autism assessment, to provide, for example, developmental or corroborative information.

- Offering flexibility around appointment times to accommodate higher education, work, or care commitments the person may have.

- Providing a shorter assessment letter that the person can share with an employer if they wish to.

Specific considerations for conducting an autism assessment with people approaching transition can include:

- Considering the age and developmental stage of the person and which semi-structured assessment measures are appropriate to their needs.

- Considering joint autism assessments between the children and young people, and adult services.

- Developing protocols for sharing information between services if the person is due to transition to adult services after screening and triage processes have taken place at a children and young people service.

Stage 5: Post-assessment support

Receiving or not receiving an autism diagnosis can mean different things to different people. Some people experience a sense of validation. For others, the clinical assessment conclusion can come as a surprise and feel unsettling or upsetting, at least initially. Family/carers and partners can similarly experience a range of emotions about this. Members of a family can have shared or unique responses; not all will feel able to have open and in-depth conversations about this (3,6,11,13,39). Therefore, having time to talk through the assessment outcome (and formulation) and to ask questions is important.

Some people and their family/carers can benefit from further support or intervention after an autism assessment. Post-assessment input can be offered by health, social care, education and voluntary, community and social enterprises. Some people benefit from short-term support by one service, while others may require several types of input either sequentially or concurrently.

Autism assessment services can be well placed to provide targeted interventions for autistic people and signposting for people who are not diagnosed as autistic.

Offering post-assessment support for people who are not autistic

Some people seen for an autism assessment are not diagnosed as autistic. Whether they receive an alternative (differential) diagnosis can depend on factors including:

- The skill set of the clinicians who assess the person (for example, whether they have the training and expertise required to assess other conditions).

- The scope of the assessment (that is, whether other conditions have been sufficiently investigated in order to be able to reach a firm clinical conclusion).

- Commissioning arrangements (for example, whether the service is commissioned to provide clinical conclusions about diagnoses other than autism).

Signposting and referral for further assessment or support

Many people who are not diagnosed as autistic may benefit from further signposting and provision of resources, support or intervention after being seen for an autism assessment. If these are available, it can be useful to share a list of resources, pertaining to health, social care, education, occupation or third sector organisations, locally and nationally. Some people who are not diagnosed as autistic will require a referral for further assessment or support by another team (for example, specific mental health service, an ADHD service). To avoid unnecessary delays, there should be a standardised policy about which service can make onward referrals. For example, this could be the GP, or a clinician at a mental health service, who may be better placed to make referrals or has a gatekeeping function within referral pathways. Assessment outcome documentation can be a useful appendix to any further referrals.

Offering post-assessment support for autistic people

Post-assessment support for autistic people can comprise:

- further assessment

- enhanced understanding of strengths

- development of a passport or self-disclosure tools

- signposting and provision of resources

- individual or group psychoeducational interventions focused on autism

- individual or group psychosocial interventions focused on mental health and emotional wellbeing

- individual or group interventions for family/carers

- peer support and mentorship

- personalised care and recommendations for social prescribing

- crisis intervention

- liaison with other services.

Further assessment