Equality and health inequalities statement

This national framework sets out the principles that should underpin the planning, design and delivery of an autism assessment pathway that works for everyone irrespective of where they live, their background, age, ethnicity, sex, gender, sexuality, disability, or health conditions. Implementation of this national framework will include taking actions to reduce known sources of health inequality that exist in access to, or experiences of, an autism assessment across England.

Foreword

Demand for autism assessments has risen rapidly over the past 20 years. Investment in autism assessment capacity has not kept pace with this growth; demand now far exceeds available capacity. Waiting lists for autism assessments across England have reached unsustainable levels. In July 2022, NHS Digital reported there were more than 125,000 people waiting for assessment by mental health services; an increase of 34% from October 2021 (1). These data show that most people wait longer, often much longer, than the three-months recommended in clinical guidelines for an autism assessment to begin (2) and the 18-week maximum waiting time for treatment to begin, as set out in the NHS Constitution (3). As demand continues to grow and capacity has remained stable or has dropped, the demand-capacity gap continues to widen.

In addition to long wait times, improvement in other areas of the autism assessment pathway is also needed. This includes improving the quality of information and support provided during and after assessment, increasing the ease and efficiency with which people transition through stages of the pathway and reducing people’s uncertainty about the process. We know services are working extraordinarily hard to keep pace with rising demand, but on account of the demand-capacity gap, the ability to provide timely assessment and support for people is not often currently possible. Strategic action is needed.

The Autism Act 2009 set a statutory duty on NHS organisations and local authorities to provide appropriate services to assess autism in adults and to support autistic adults post-diagnosis. In 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan committed to reducing autism assessment waiting times and delivering packages of post-assessment support for children. In 2021, the National strategy for autistic children, young people and adults (4) expanded upon this ambition, by committing to timely access to diagnosis and demonstrably improved autism assessment pathways for people of all ages by 2026.

We recognise that achieving these policy ambitions requires a multifaceted response, that should include increasing the supply of a specialist workforce, ensuring that resource allocation to autism assessment services is sufficient to close the demand-capacity gap, while adhering to best practice clinical guidelines and deploying existing resources as effectively and efficiently as possible. Increasing workforce supply and resource allocation to autism assessment services are outside of the scope of this work but should remain a focus in efforts to achieve national policy ambitions.

With respect to effective and efficient use of existing resource, we have developed two documents to support integrated care boards (ICB) in England. We anticipate ICBs will use these documents to work with other organisations that may provide some of the autism assessment offer in their integrated care system (ICS) footprint. We have produced this national framework that sets out general principles to be applied during the commissioning cycle for an autism assessment offer in each area of the country. We have also produced operational guidance that places these general principles in operational context in terms of how they can be applied in each area.

Both documents have been created with input from clinical, lived experience, scientific, commissioning and service management experts. Both documents incorporate relevant, evidence-based recommendations from NICE guidance.

Tom Cahill, National Director, Learning Disability and Autism Programme, NHS England.

Claire Dowling, Programme Director Autism, Learning Disability and Autism Programme, NHS England.

Dr Roger Banks, National Clinical Director, Learning Disability and Autism Programme, NHS England.

Brief introduction to autism diagnosis

Autism spectrum disorder (referred to as autism in this national framework and the operational guidance) is the official name of a diagnosis within a broader category called neurodevelopmental disorders in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, eleventh edition (ICD-11; 5) [1]. The ICD is the only assessment manual that officially applies in the NHS in England. This global assessment standard states that for a person to be diagnosed as autistic, all the following criteria must apply:

- “Persistent deficits in initiating and sustaining social communication and reciprocal social interactions that are outside the expected range of typical functioning given the person’s age and level of intellectual development.

- Persistent restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities that are clearly atypical or excessive for the person’s age and sociocultural context. [2]

- The onset of the disorder occurs during the developmental period, typically in early childhood, but characteristic symptoms may not fully manifest until later, when social demands exceed limited capacities.

- The symptoms result in significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Some people with Autism Spectrum Disorder are able to function adequately in many contexts through exceptional effort, such that their deficits may not be apparent to others” (5)

ICD-11 was endorsed by the World Health Organisation in February 2022 but does not have a mandatory implementation date. This means that each health service around the world that uses the ICD manual sets its own timeline for adoption. In the NHS in England, there is, as yet, no definitive date for the ICD-11 to be mandated; the tenth edition of the ICD (6) remains the mandated information standard for use about diagnosis while clinical records systems are updated to reflect the eleventh edition. ICD-11 codes can be used locally before being mandated nationally. However, ICD-11 codes cannot yet be submitted to national datasets and will need to be mapped onto ICD-10 codes for this purpose, see this page for more information.

Autism is also a diagnosis described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5; 7). The DSM-5 is the official assessment manual in the United States of America. It has no official status in the NHS in England. Despite this, given its prominence in the scientific literature, DSM diagnostic criteria are referred to in clinical guidelines. Also, some standardised assessment tools used in England were designed using DSM-5 criteria or criteria from the previous edition. Additionally, some services used DSM-5 criteria while awaiting publication of the latest edition of the ICD. For consistency across the NHS, ICD-11 criteria should be used for the primary description of autism, but assessment tools based on DSM criteria and health record codes based on ICD-10 can still be used.

There are no diagnostic biomarkers for autism. This means there are no objective biological tests or scans used in confirming or refuting an autism diagnosis [3]. Autism is therefore a clinical diagnosis; diagnosis is based on expert clinical judgement about whether a person’s observable behaviour and their own or another person’s report about their developmental history and behaviours meet the clinical threshold for each of the above criteria.

None of the individual autism diagnostic criteria are exclusive to autism; that is, there is considerable overlap in diagnostic features of several communication, neurodevelopmental and mental health conditions (8). Autism also co-occurs with other conditions more often than it occurs as a sole diagnosis (9,10). For these reasons, consideration of differential, that is, alternative or co-occurring diagnoses, is necessary as part of an autism assessment to establish whether a person’s behaviour is explained by none, one, or more than one of a range of possible diagnosable conditions. Autism should not be assessed without also considering the possibility of differential or co-occurring diagnoses.

The purpose of an autism diagnosis

Autism is not an illness or disease, and autistic traits are not a universally agreed intervention target for every autistic person. However, an autism diagnosis can serve several important purposes as set out below. This is why universal, equitable and timely access to autism assessment in every ICB is important.

Firstly, an autism diagnosis is important in the context of healthcare. While not the case for all, many autistic people do seek interventions that are safe and effective for improving particular skills and abilities that overlap with diagnostic traits, for example, language and communication (11). A diagnosis enables clinicians to recommend interventions that have been tested for safety, acceptability, efficacy and effectiveness with people meeting the same diagnostic criteria as the person they are supporting; a critical tenet of evidence-based care. This may be, for example, interventions with an autistic person (12), or parents (13), to improve communication, behavioural or well-being outcomes.

Secondly, an autism diagnosis is a mechanism to ensure reasonable adjustments are made in general physical health or mental health services (14,15). A diagnosis is often vital in clinical formulation and treatment planning for co-occurring conditions. For example, some common mental health interventions are known to be less effective or can require adaptations for autistic people (16). For example, cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety or depression (17) or intervention for feeding and eating disorders (18).

Thirdly, clarity about autism diagnosis can be validating for many people in their day-to-day lives. For example, this can help with the development of a positive autistic self-identity and foster connections with the autistic community (19).

Fourthly, an autism diagnosis can help facilitate access to some forms of statutory protection beyond the healthcare context. For example, an autism diagnosis may be considered when a person seeks an Education, Health and Care Plan, a legal document setting the support children and young people receive. The Equality Act 2010 can be a source of protection for people with a disability, the definition of disability according to the Act is available here. Further, autistic people have been shown to be better able to advocate for reasonable adjustments in the workplace if they have clarity about an autism diagnosis (20). Additionally, according to the statutory guidance (21) of the Autism Act 2009, autistic adults are entitled to a care assessment under the Care Act 2014 and, in some cases, an assessment report may be considered in assessing a person’s support needs.

For an undiagnosed autistic person access to personal understanding, healthcare, education, social care, reasonable adjustments in the workplace, statutory protection from discrimination, or benefits may be withheld. For these reasons, it is important that ICBs do not restrict or withhold access to an autism diagnosis, for example, because locally a decision has been taken by health to conduct only a needs-based assessment. Barriers to a diagnosis increase a person’s risk for poor outcomes in life, for example, late diagnosed autistic adults commonly experience multiple forms of abuse (22) and can experience poorer mental health, suicidality or hospital admission (23,24). As a result, autistic people, and especially people without an intellectual disability, represent a significant proportion of the mental health inpatient population in England (25).

An autism diagnosis should always be made by clinical professionals in a health service. Delayed or unequal access to autism assessment can result in missed opportunities for support from education, social care, voluntary, community and social enterprise. In turn, this can increase the likelihood that people require restrictive and costly hospital care (23,24). That is, while broad and timely access to an autism diagnosis is costly to the health service, narrow and delayed access may be more costly still.

Definitions of terms used

- Suspected or possible autism: an administrative term used to denote when a person is identified as having traits and difficulties suggestive of autism, that warrant formal assessment.

- Autism assessment: an assessment that takes place to determine if a person with suspected or possible autism meets the diagnostic criteria for autism (that is, is autistic). It is essential that the assessment of autism is not undertaken in isolation from screening or assessment of other conditions that may be the cause of, contribute to, or be associated with traits and difficulties identified; often referred to as differential or co-occurring diagnoses.

- Autism assessment service: any service commissioned to conduct autism assessments, as described above, when these represent a significant proportion of the service’s activity. Some autism assessments take place in services that do not routinely conduct autism assessments, such as, by secondary care mental health services, in an inpatient ward or during contact with the criminal justice system. This national framework and the operational guidance were not developed with these services in mind. However, any service that conducts autism assessments should consider the principles of service design and delivery in both documents. This term is used to refer to a range of services with a variety of local naming conventions, including child development centres, social-communication teams, community paediatrics, neurodevelopmental assessment teams, children and young people’s mental health services, services providing autism assessments or independent services.

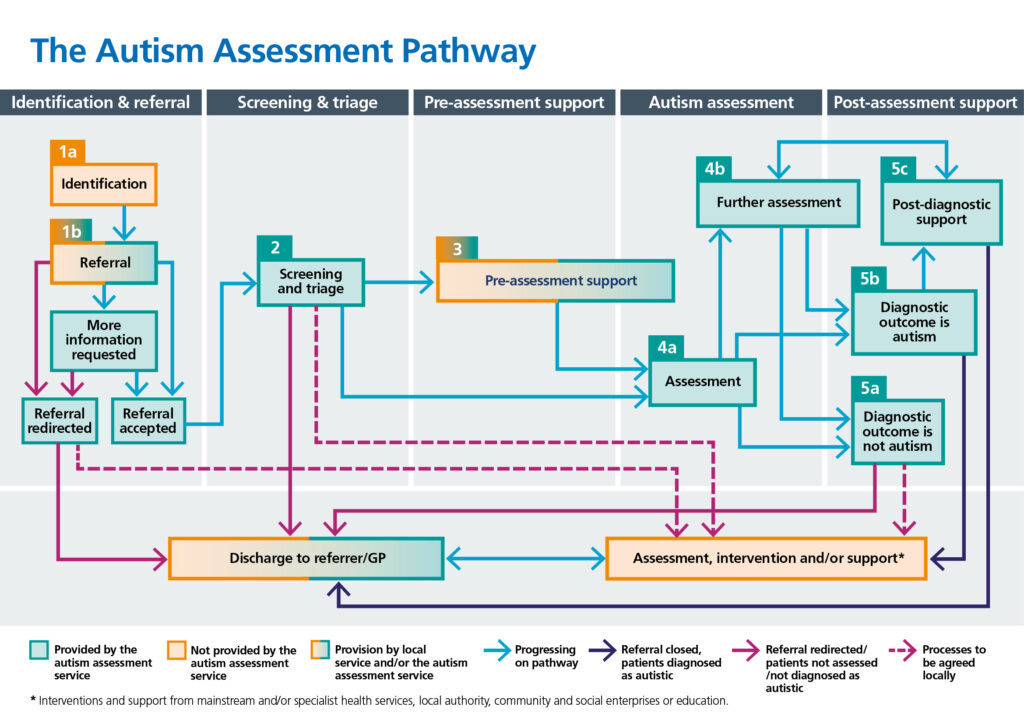

- Autism assessment offer: the overall NHS autism assessment capacity in each area when capacity for all autism assessment services is considered collectively. Services contributing capacity towards the autism assessment offer may be a combination of NHS services and independent providers.

- Autism assessment pathway: the journey a person takes from the moment they are identified as potentially warranting an autism assessment until the point at which they are discharged from an autism assessment service. Discharge can take place, for example, after there has been a screening and triage process that suggests a full assessment is not clinically indicated, after the autism assessment has been conducted and the person is given an assessment outcome, or after post-assessment support has been delivered. See Figure 2 for a graphical schematic depiction of the pathway.

- Standard autism assessment: an autism assessment conducted by a single clinician, or two or more clinicians, appropriately qualified to diagnose or rule out possible autism. The assessment includes at a minimum, a clinical interview, behavioural observation, integration of developmental and corroborative information and consideration of possible differential and co-occurring diagnoses not identified at triage (especially when there has been a delay between initial referral, triage and main assessment).

- Enhanced autism assessment: an autism assessment conducted by two or more clinicians, appropriately qualified to diagnose or rule out possible autism. The assessment includes at a minimum, a clinical interview, behavioural observation, integration of developmental and corroborative information, use of validated assessment tools, a broader assessment of clinical presentation (such as estimated intellectual functioning or sensory processing) and additional liaison with referrers and other involved service(s). Siblings, partners or friends may provide corroborative information.

- Clinician or clinical professional: a health professional who has graduate or postgraduate qualifications in a health or related discipline, as well as current registration or accreditation with one of the following professional bodies: the General Medical Council, Health and Care Professions Council [4] or Nursing and Midwifery Council. Registration with a professional body does not, by definition, equip an individual to be competent in autism assessment, without appropriate skills and training in autism assessment and diagnosis.

- Staff under clinical supervision: people who may work directly with people being assessed by an autism assessment team and their family/carer under the supervision of a clinical professional, but who do not themselves have a clinical qualification or accreditation with professional bodies listed above. This includes, for example, assistant psychologists and staff in training.

- Autism assessment team: the multidisciplinary team that works in an autism assessment service. Professionals in an autism assessment team must collectively have skills to assess autistic traits and differential and co-occurring diagnoses. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends professionals who should be represented in teams for children and young people under 19 years of age, and teams for adults.

- Autism assessment tool: a standardised assessment tool that has been designed and carefully tested to provide clinical professionals with information that can inform their decision about whether somebody is autistic. While these tools provide useful information, they are not diagnostic on their own and must be interpreted by clinical professionals. These include questionnaires, structured observational assessments, and developmentally focused interviews.

- Pre- and post-assessment support: any support that a person or their family/carer is offered while they are on the autism assessment pathway. This includes providing people with high-quality, accurate and timely information throughout the process such as communication about the assessment process, updates about what will happen and when, and where and how to get practical support. This may include signposting or facilitating introductions to other services within or beyond health. Post-assessment support can include signposting to sources of help for other conditions or provision of support around accepting and understanding an autism diagnosis. This phrase can be used to include evidence-based interventions, but also includes other broader forms of educational or informational support.

The impact of COVID-19 on autism assessment services

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on autism assessment services was acute and prolonged; some autism services were suspended entirely, or capacity was profoundly reduced for periods throughout 2020 (26). Some services were disrupted due to staff redeployment to the COVID-19 response effort, or to facilitate services to rapidly change their protocols and procedures, such as using telehealth methods, social distancing and personal protective equipment, or to adhere to COVID-19 lockdowns (27). Additionally, autistic people and those supporting them reported exacerbations of pre-pandemic health and educational inequalities (28, 29). This suggests that people referred for autism assessment may be more likely to also have unmet social care, mental health or educational needs than was typical pre-pandemic.

The purpose of the national framework and operational guidance

Despite successive policy commitments to improve the quality and increase capacity of autism assessment services in England, gaps remain in setting out actions that need to be taken to achieve these improvements. Here, we set out two interrelated pieces of guidance to address this gap.

We have developed a national framework to deliver improved outcomes in all-age autism assessment pathways. It has three sections:

- a brief overview of the most relevant policy context

- general principles underpinning autism assessment services

- how to apply these principles during a commissioning cycle.

Additionally, we have developed operational guidance to deliver improved outcomes in all-age autism assessment pathways. The operational guidance outlines detailed information about how to deliver individual autism assessment services and how these should be configured to form an overall autism assessment offer in each area of England. This guidance is designed to help areas ensure that every person referred for an autism assessment experiences an efficient, high-quality pathway, with clarity about what will happen and confidence in the diagnostic outcomes. The guidance is comprised of three sections:

- specifications for the five stages of the autism assessment pathway

- common variations in how the autism assessment is conducted

- non-clinical tasks commonly undertaken by autism assessment services.

Together, these documents are intended to help people in commissioning, clinical, management, lived experience and administrative roles, to make decisions to deliver high quality all-age autism assessment pathways. Specifically, these documents are designed to be used to:

- Reduce the number of referrals to autism assessment services that are declined on account of insufficient information being provided.

- Reduce the number of people referred to autism assessment services when a referral is not warranted, for example, when there is no reason to suspect possible autism or when a referral to a different service would be more appropriate.

- Increase satisfaction of people referred for an autism assessment, including those who are not assessed and those who are not diagnosed as autistic, and by their family/carers, irrespective of their age, ability, or background.

- Increase confidence in decisions among all stakeholders, including the person assessed, their family/carers and all organisations that the decision is relevant to.

- Reduce the number of people who are referred to and assessed by multiple services for different conditions, especially when duplicated assessment occurs and when a single service has the capability required to conduct all the assessments that are clinically indicated.

- Increase the proportion of people who receive packages of support while awaiting assessment and soon after receiving a diagnosis.

- Maximise resource spent on well evidenced support and minimise the amount of resource allocated on un-evidenced or under-evidenced interventions.

- Ensure that autism assessment services offer attractive career options by having varied and stimulating roles for all relevant clinical professionals, to aid workforce recruitment and retention.

This national framework does not intend to:

- facilitate the complete elimination of autism assessment waiting times

- establish a single service to assess for all neurodevelopmental conditions (commonly referred to as neurodevelopmental services)

- replace existing clinical guidelines

- address models of ongoing intervention and care, beyond the immediate post-assessment period.

For more information about how both the national framework and operational guidance were developed, including the evidence considered and stakeholders consulted, see Appendix A.

A brief overview of policies and laws relevant to autism assessment service delivery is provided below.

Building the Right Support (2015)

The Building the Right Support national plan (30) and national service model (31) were developed to support the NHS and local authorities to reduce the number of autistic people and people with an intellectual disability in mental health hospitals, by increasing the provision of support in their local community.

The NHS Long Term Plan (2019)

The NHS Long Term Plan set out a 10-year vision for improving the NHS in England, including, for the first-time, recognising autism as a national priority. The commitments in the Long Term Plan outline a vision for changes needed in the whole NHS by 2029 to best support autistic people to lead happier, healthier, and longer lives, including:

- “Reduce waiting times for specialist services”

- “Achieving timely diagnostic assessments in line with best practice guidelines”

- “Together with local authority children’s social care and education services as well as expert charities, we will jointly develop packages to support children with autism or other neurodevelopmental disorders”.

The national strategy for autistic children, young people, and adults (2021)

The national strategy for autistic children, young people and adults: 2021 to 2026 (4) committed to ‘demonstrable improvements’ in reducing waiting times and improving assessment pathways across all age groups and across the country. Additionally, an autism strategy implementation plan was published for 2021 to 2022 (32).

Requirements of the Autism Act 2009 are that the national autism strategy is kept under review and that there is always associated statutory guidance in place setting out what local authorities, NHS organisations, and NHS Trusts must do to implement the current autism strategy and to deliver on the requirements of the Act.

The Health and Care Act 2022

The Health and Care Act 2022 represented a landmark re-organisation of health and care services in England with the establishment of integrated care systems (ICSs) across England.

ICSs are partnerships of organisations that come together to plan and deliver joined up health and care services across the ICS footprint. They are designed to improve health outcomes for their population and create efficiencies by making it easier for local authorities and NHS organisations to collaborate. Within an ICS, an ICB is the statutory NHS organisation, superseding Clinical Commissioning Groups, that develop a plan for meeting the health needs of the population, managing the NHS component of the budget required to achieve that plan and arranging for the provision of health services.

Personalised care

The Long Term Plan stated that personalised care, whereby people get more control over their own health and more personalised care when they need it, will become business as usual in the health and care system (33). Guidance about how to achieve this by 2023/2024 has also been published (34). Further information is available on the NHS England website and in the Finance, Commissioning and Contracting Handbook for the NHS England Comprehensive Model for Personalised Care.

Universal personalised care is defined by six components.

- Shared decision making – people are supported to understand the care, treatment and support options available, as well as the risks, benefits and consequences of each option and to use this information to decide on their preferred course of action.

- Personalised care and support planning – this is about focusing on what matters to the person and their skills and strengths, as well as their clinical and support needs. It leads to a single plan, owned by the person and accessible to the people supporting them.

- Enabling choice – the NHS Constitution for England (3) recognises patients’ right to make informed choices about the services commissioned by the NHS and information to support making decisions about these choices.

- Social prescribing and community-based support – this enables all local agencies to refer people to a social prescribing link worker to connect them into community-based support, building on what matters to the person and their family/carers, as identified through shared decision making, personalised care and support planning, and making the most of community and informal support.

- Supported self-management – this refers to increasing the knowledge, skills and confidence a person has in managing their own health and care, referred to as patient activation. This is done through putting in place interventions such as health coaching, self-management education and peer support.

- Personal health budgets – this is an amount of money to support a person’s identified health and wellbeing needs, planned and agreed between them and their local ICB. This may lead to integrated personal budgets for people with both health and social care needs.

Criminal justice

NHS England’s health and justice and specialised commissioning teams are responsible for commissioning healthcare for people across a wide range of secure and detained settings including prisons, secure facilities and immigration removal centres. This national framework and operational guidance should be considered in the context of existing guidance from these teams about healthcare in these contexts. This includes, for example, meeting the healthcare needs of adults with a learning disability and autistic adults in prison (35) and provision for people with a known or suspected learning disability, autism or both in liaison and diversion services (36).

In response to an inspectorate report on neurodiversity in the criminal justice system (37) the Ministry of Justice has published a neurodiversity in the criminal justice system action plan, this includes a focus on identification and diagnosis.

Principles that guide commissioning of an autism assessment service

Here we set out 10 principles that should guide all decision making by anyone planning, designing, procuring, delivering, and evaluating an autism assessment offer. These principles are that an autism assessment offer should always be:

- ethical

- evidence based

- respectful

- delivered by an appropriately skilled multidisciplinary workforce

- a comprehensive, coherent offer

- accessible

- co-designed by clinicians and people who access the services

- based on shared and current conceptualisation of autism

- transparent

- described in, and informed by, national statistical data.

These principles are set out in the sections below.

Ethical

Autism assessment pathways, from the outset (that is, from the time potential autistic traits are identified, up until discharge from an autism assessment service), should not cause harm to people. This fundamental principle should guide decision making at every level to ensure services design and delivery is ethical. Ethical considerations should be made on several grounds.

Firstly, consider if actions taken by an autism assessment service have the potential to harm someone who is referred for assessment by that service. This may be, for example, considering how service level exclusion criteria or the sharing of inaccurate or potentially harmful information with someone before, during or after an assessment, could potentially cause harm.

Secondly, consider if actions taken by people performing commissioning functions are appropriately protecting people from risk. This could include, for example, taking appropriate precautions to ensure an ICB is satisfied each service that contributes to the autism assessment offer in each area is appropriately regulated, or when a service is not registered with the Care Quality Commission, that the ICB is satisfied with the steps taken to appraise that service and communicate what this means to prospective patients. Additionally, if a service routinely produces assessment decisions that are not trusted by other providers, consider the potential for this to cause harm both to the person assessed and to the wider autism assessment offer in the area. This may result in another service re-validating a decision incurring additional resource and questioning the decision may be distressing for the person who was assessed.

Thirdly, consider if activities commissioned or delivered represent value for public funds. This may be, for example, considering if an intervention or process within the autism assessment offer has evidence to demonstrate it is the most effective means of achieving its intended outcome. When evidence is found of superior cost effectiveness to an existing practice, it should be replaced.

Finally, consider if claims made by autism assessment services are well founded. Any intervention delivered by an autism assessment service that claims to lead to a potential therapeutic benefit, such as, an improvement in a skill or a reduction in a symptom should have evidence of efficacy and effectiveness and have been tested for potential adverse outcomes. It is not ethical for services to claim an intervention produces therapeutic benefits when scientific and clinical consensus have not yet been established.

Evidence based

For the NHS to achieve its founding principles to provide the highest standard of excellence and best value for taxpayers’ money, care must be designed and delivered based on the best, currently available evidence.

NICE has published three clinical guidelines [5] that, together, describe how health and social care services should be delivered to identify, assess for and care for people diagnosed as autistic. The autism NICE clinical guidelines were also instrumental in the development of a NICE quality standard for autism [6]. The NICE autism publications are:

- Clinical guideline 128: Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis (2)

- Clinical guideline 170: Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: support and management (38)

- Clinical guideline 142: Autism spectrum disorder in adults: diagnosis and management (39)

- Quality standard 51: Autism (40)

NICE guidelines remain the primary source of information to inform decisions about how to apply evidence to service design and delivery. Compliance with NICE guidelines should always inform decision making about design and delivery of a service and purchasing of assessment services from other NHS or independent services. Clear, accurate, current and accessible information about the extent to which each service providing autism assessments complies with NICE guidance should be available to inform people’s choices.

A significant amount of scientific research evidence about the assessment, diagnosis and support for autistic people has been published since NICE guidelines were last updated. Both this national framework and operational guidance refer to additional research that was not considered in the development of the autism NICE guidelines. These documents are not intended to replace NICE guidelines, but to supplement or extend some recommendations. Some NICE guidelines have had varied implementation. For instance, where NICE refers to the need for and composition of multidisciplinary teams it does not specify the precise sources and degrees of multidisciplinary input required for every assessment. These documents seek to add additional guidance to inform decision making in these areas. NICE guidelines remain the primary information source to justify resource allocation on interventions offered for autistic people after diagnosis.

It is the responsibility of individual clinicians, their respective professional bodies and people in commissioning roles to ensure public resources are spent on well evidenced services and not on un-evidenced or under-evidenced alternatives.

Together with the Innovation Agency, NHS England have produced a practical guide to support commissioners to interpret and use evidence.

Respectful

Words matter – a lot. The terms used to communicate with, and about, autistic people can influence people’s attitudes about autism.

We recommend that autism assessment pathways use language that categorises autism in diagnostic, but not negative or deficit-based terms. Autism should not be referred to as a disease or illness. Using respectful, inclusive and destigmatising language is a priority. We have set out the language principles we have used in this document that we recommend others adopt in Table 1.

Table 1. Language principles guiding this document.

| Do | Do not |

| Use consistent terminology to describe an autism diagnosis for everyone and add details about other diagnoses a person may have, such as an intellectual disability, if appropriate. | Use functioning level descriptors, such as, high-functioning, or low-functioning autism. These are not and never were diagnoses. |

| When possible, ask people what language they prefer to use and respect this preference. | Be rigid about the terminology you use to talk about autism or about autistic people. |

| When communicating with a person or to a group of people without knowing their terminology preferences, use the more widely preferred identity first language, for example, say “she is autistic” instead of the less preferred person-first language, for example, saying “she has autism”. | Correct a person’s terminology choice about themselves or their family members. |

| When appropriate, describe autism as a neurodevelopmental disorder or neurodevelopmental disability. | Refer to autism as a disease or an illness. |

| Use descriptive and clinically informative language about a person’s strengths and difficulties. | Use negative or value-laden language when describing a person’s diagnosis, such as, suffers from autism, or struggles with autism. |

| Use the language from the version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems that is valid and current at the time at which a person is diagnosed. | Use assessment categories from earlier editions or international variants of diagnostic manuals, unless the person was diagnosed when the term was still in use. |

| Use descriptive names for teams, services or job titles, for example, autism assessment service, specialist autism team or autism team lead. | Use acronyms when naming or referring to teams, services or people’s job titles, such as, an ASD team or ASC assessment lead. |

Delivered by an appropriately skilled multidisciplinary workforce

An important feature of an effective autism assessment pathway is that within every service, there needs to be an appropriately skilled multidisciplinary team that can deliver high-quality assessments. An appropriate clinical workforce includes:

- Good leadership. Each assessment service should be led by an appropriately qualified, skilled and experienced clinical service lead. Some services may have separate operational and clinical leadership.

- The right skill mix. The combination of skills represented in each autism assessment service should be determined by the clinical needs of the people who routinely present for assessment at that service. For example, the clinical professionals in any autism assessment service should, together, have experience and expertise in assessment of neurodevelopmental (including intellectual disability), language and communication, and behavioural and mental health conditions, as these are commonly differential or co-occurring conditions. The precise proportion of these skills required will depend on the service.

- Qualified staff. Clinical professionals should all meet the qualification, regulation and current professional registration requirements to practice by their respective professional bodies. Clinical professionals from a limited number of professional disciplines (for example, a paediatrician, psychiatrist, clinical psychologist) are qualified to conduct each component of an autism assessment. Clinical professionals from many clinical professions (for example, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and some types of nurses) are qualified to conduct some but not all components of an autism assessment; they should conduct autism assessments as part of a multidisciplinary team where the team is collectively qualified to conduct all required components of the assessment, see the operational guidance for more detail. Some clinical professionals may have additional training and qualifications to practice at multi-professional consultant or multi-professional advanced clinical practice level to increase the number and diversity of professions represented in leadership roles. When these include training and assessed capability to conduct components of autism assessments, such as, for example, the autism credential, this may increase capability in relation to the components of assessment a professional can undertake. Some clinical professionals may have some additional non-clinical qualifications (for example diplomas, undergraduate or postgraduate degrees); this does not change their qualification to conduct each component of an autism assessment. Some components of assessment can be undertaken by staff under clinical supervision.

- Access to clinical supervision. The type, amount and level of clinical supervision for clinicians and unqualified staff should meet the requirements outlined by relevant professional bodies and training institutions. In service planning, supervising clinicians should be consulted about how much time they need for clinical supervision of both qualified and unqualified staff.

- A comprehensive workforce. Autism assessment services should identify the total number of clinical professionals and professionals under clinical supervision needed to deliver a high-quality, comprehensive assessment pathway with capacity to meet anticipated demand for the year ahead, to facilitate progress against wait time policy ambitions while delivering post-assessment support. This should include focused efforts to identify and address any issues with recruitment and retention.

- Administrative staff capacity that matches demand. The amount of administrative support should be such that there is capacity to manage tasks including, appointment scheduling, liaison with people and their family/carers, coordination of staff availability, room bookings, acquisition of any assessment tools that require purchasing, ongoing input with preparation of letters and outcome documentation, and data entry into electronic clinical records. Given the limited number of appropriately qualified clinicians available to recruit to longstanding clinical vacancies in autism services, these administrative tasks should not be completed by clinical staff.

- Informed referrers. The autism assessment service should provide training about autism to organisations that refer people for autism assessments in order to increase efficiency and use of resources. This could include, for example, information about writing a focused referral letter, information about valid and reliable screening tools a person or their family/carer can complete to better understand if an autism assessment would likely benefit them, the remit of the service, and need for other services or joint working. This training is in addition to the Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism.

- Time to upskill non-specialist services. Autism assessment services are hubs of autism expertise. When feasible, these services should deliver training, consultation and liaison, and supervision, to increase the breadth and depth of knowledge about autism across the NHS. This could include, for example, how to identify possible autism, information about the local autism assessment offer, scenarios when an autism assessment referral may not be warranted, and tips about how to support an autistic person receiving treatment for another condition. This upskilling could increase collaborative working, foster opportunities for joint assessment or ensure people waiting for an autism assessment are not excluded from other services.

- Succession planning. Services should complete and maintain talent and succession plans in advance of roles becoming vacant, such as when staff go on extended periods of planned leave, are promoted, leave a service or retire. This should include identifying staff who may be ready for promotion and supporting their training and development to attain this. This may reduce instances of dropped capacity when positions are vacant for periods during lengthy recruitment processes.

- Attractive jobs. Services should work to ensure staff are actively supported, have fulfilling and varied roles and well-paced development opportunities, such as secondment and training, as this may help reduce common recruitment and retention challenges.

Another important consideration is that there is an appropriately skilled and trained workforce performing commissioning functions for the autism assessment offer. An advanced practice credential about supporting people with learning disabilities, including people with a learning disability who are autistic and a learning disability and autism version of the principles of commissioning for wellbeing are available.

A comprehensive, coherent offer

NHS and local authority organisations should ensure that, collectively, provision is available for people of all ages to have autism assessments, and for there to be support available pre-assessment and following a recent diagnosis of autism (21).

The autism assessment offer in any given ICS area can include different combinations of the following types of services:

- For children, community paediatric teams, such as in child development centres either from within the ICS or from another ICS.

- For children and young people, community child and young people’s mental health service either from within the ICS or from another ICS.

- For adults, services providing autism assessments, described in NICE guidelines as a specialist autism team, either from within the ICS or from another ICS.

- Independent services.

- Voluntary, community, and social enterprise services.

- Educational organisations.

Change and uncertainty can be anxiety-provoking for many people, particularly autistic people. It is important that the experience from referral through to discharge from autism assessment services is as continuous and consistent as possible from the perspective of the person being assessed and their family/carers. For example, when feasible, professionals in contact with the person being assessed should remain consistent (that is, when possible, the same professional contacts them or responds to queries), information could be delivered about the stages and processes in the pathway at the outset and in a standardised format, consistent terminology is used throughout the process, and meetings could take place in the same location, or on the same day/time, if the person would prefer this.

Partnership working across an ICS is important to ensure that autism assessment services work efficiently alongside each other and other care and support available across the ICS. Pre-assessment and post-diagnostic support should be available either through statutory services, education, voluntary, community, or social enterprises or independent providers. Links should be strong between a range of local organisations. Contact details for general local health and social care services, education support, regional and national charities, third sector organisations and personalised approaches should be shared and widely available to ensure the maximum amount of support is available.

There are also specific mandated partnership working requirements in the Care Act 2014 that need to be adhered to. In particular, standard 4 of the commissioning for better outcomes route map (41) that supports the implementation of the Care Act 2014.

Accessible

Autism assessments are available to all, irrespective of gender, ethnicity and culture, disability, age, sexual orientation, religion, belief, gender reassignment, pregnancy and maternity or marital or civil partnership status (3).

Reasonable adjustments are required for some people referred to the autism assessment pathway to fulfil this duty to parity in provision. For example, people who have visual or hearing impairments, are minimally verbal, have sensory sensitivities, social communication difficulties, or have no fixed access to a postal address, may find certain modes of communication more difficult to navigate. This includes telephone calls, especially if these are unplanned, with unfamiliar people or involving important discussions. Additionally, some people may find travelling to clinic or being assessed in person overwhelming experiences. Therefore, a flexible approach should be adopted to service provision when feasible, balancing choice and accessibility needs with risk, clinical utility and resource available.

Some people referred for an autism assessment, or their family/carers, do not speak or read fluent English, or they may communicate using sign language. For an autism assessment to be accessible in these instances, an interpreter may be required for a clinical interview, behavioural observational assessment or assessments with family/carers, or the person may be seen by a national service specialising in sign language assessments. Additionally, services need to be accessible for interpreters and should be commissioned by the organisation’s interpreter service. If possible, providing continuity for people using the interpreter service is beneficial. Commonly used written resources should be translated into some languages that are common in a service. Asking family/carers to interpret or translate should be avoided, whenever possible.

Health literacy universal precautions

In England, 43% of adults do not have adequate literacy skills to routinely understand health information and 61% of adults do not have adequate numeracy skills in this regard (42). Variation in health literacy plays a powerful role in many health inequalities (43).

Embedding a universal precautions approach in autism assessment pathways avoids stigmatising people with low health literacy. Health literacy can be situational. People with proficient health literacy skills may sometimes have trouble understanding health information, especially when anxious or in an unfamiliar environment.

A universal precautions approach to health literacy should be adopted within the autism assessment pathway. This calls for health care services and professionals to assume that all patients and family/carers can have difficulty understanding information and accessing services. It helps address the negative impact of low health literacy on people and the health system. This means not automatically assuming that people and their family/carers are fully clear about what the pathway comprises, how to access this, what the assessment can entail and the range of potential outcomes. Pathways should therefore:

- Develop clear and accessible written materials, such as webpages, leaflets, or posters, to outline the autism assessment offer in the area, as well as describing the assessment pathway, assessment process and potential outcomes for the specific service, using the NHS standard for creating health content.

- Use multiple formats, like easy read, plain English, video or audio, to communicate important information to ensure certain groups (such as people with an intellectual disability or visual or hearing impairment) receive information in accessible formats, using the NHS accessible information standard.

- Reduce the complexity of the pathway and terminology used to describe it.

- Prepare accessible autism diagnostic reports.

- Educate staff working within the pathway about the importance of health literacy and adoption of a universal precautions approach.

Access is based on clinical need

A guiding NHS principle is that access to an NHS autism assessment is based on clinical need, not a person’s ability to pay (3). According to the Who pays framework, no necessary assessment, care or treatment should be refused or delayed because of uncertainty or ambiguity as to which NHS commissioner is responsible for funding a person’s healthcare provision (44). This includes when a person is accessing an autism assessment outside of the area where they normally reside.

Co-designed by clinicians and people who access the services

Partners in each ICB should listen to and act on the experience and aspirations of communities in the area. There is a statutory duty for ICBs to involve people and communities in developing plans for continual improvement of services (45).

Shared and current concept of autism diagnosis

Several frameworks have been produced to supplement NICE guidelines and support local decision makers in health and social care services, with planning, designing, procuring, and evaluating autism assessment services.

The Core Capabilities Framework for Supporting Autistic People (46) sets out the skills, knowledge and behaviours that professionals working in any health or social care setting need in order to best support people accessing these services.

Commissioning services for autistic people: A cross-system framework for commissioning social care, health and children’s services for autistic people (47) outlines a suggested framework to support ICBs to consider what they should analyse, what actions they should undertake and who they should engage with, when making local commissioning decisions about health, education and social care services for autistic people. This states that four areas are important in relation to autism assessment services:

- the level of population needs, including any waiting lists,

- the mix of services already in place (for example, NHS, independent and community and voluntary sector),

- the gaps that are evident in current provision and

- what future input from partners within the ICS is likely to be.

Autism diagnostic criteria have undergone numerous revisions since the first descriptions, due to expanded diagnostic thresholds, more public recognition of possible autistic traits, improved sensitivity of assessment tools and an increase in people previously receiving other diagnoses being diagnosed as autistic (48–51). One result of evolving diagnostic criteria, clinical practices and public ideas about autism, is the potential variation in people’s views about what an autism diagnosis is, and currently accepted best practice in assessment for autism. For an autism assessment pathway to function effectively there must be a high degree of trust between all agencies involved (that is, professionals involved in any assessment pathway should have similar and up-to-date conceptualisations of autism). This may mean working to bring different services together to foster shared understanding and to ensure outdated ideas or practices become obsolete.

Transparent

All the information that somebody may need to easily navigate the autism assessment pathway within any ICS should be clearly and transparently communicated in an accessible public forum. This could be, for example, a single webpage that lists, by name, every service that is currently part of an autism assessment offer within an ICS geography, as well as whether there is a single point of access. A summary of the information that should be made publicly available can be found in the identification and referral section of the operational guidance. This information can be shared in other locations, for example, printed leaflets or cards linking to online content could be shared with professionals who may refer people into an autism assessment pathway or be linked in other online locations, such as the local offer.

To facilitate informed patient choice and to minimise inappropriate referrals, inclusion and exclusion criteria for each service forming part of the autism assessment offer must be clear, including age cut-offs, geographic cut-offs and eligibility based on any other existing co-occurring conditions, for example, moderate intellectual disability.

Details should be clearly communicated about who can make a referral to each service, and what information this must contain. This should also detail the process by which a referral can be made, for example, with a (template) letter or completion of an online form.

When possible, the inclusion criteria, referral mechanisms and information required in the referral process should be standardised across all services that comprise the autism assessment offer, so as to reduce the need to collect the same information more than once if a person is seen by more than one autism assessment service, for example, if they are referred onward.

Subsequent stages of the autism assessment pathway should be adequately detailed, so that the person and their family/carers, and professionals working in other settings, have clarity about what will happen, how, the likely timeframe and the potential outcomes.

Details should be provided about what is offered by each service in the autism assessment offer, for example, if pre-assessment and post-assessment support is available in one service but not another, this should be clearly communicated. Additionally, information should be freely and clearly accessible about the local rules used to inform decision making for people who may seek different stages of their pathway in different services, for example, if a person is diagnosed by one service, they should be able to identify whether they can access post-assessment support at another service. This information should be available to referrers and can inform patient choice decisions.

Be described in, and informed by, national statistical data

The national strategy for autistic children, young people and adults (4) sets a goal for “demonstrable progress on reducing diagnosis waiting times and improving diagnostic pathways”. Progress towards these goals will be measured through national statistics.

Regular statistical digests are published by NHS Digital [7] about services providing autism assessments (25,52). These reports draw on statistics of mental health service activity collected through the Mental Health Services Dataset (MHSDS). All NHS-funded mental health service providers, including independent sector providers, are required to report details of all NHS-funded mental healthcare activity, including autism assessments, through this collection.

Published data about autism diagnosis services report the numbers and progress of referrals to mental health providers where the primary reason for referral is recorded as ‘suspected autistic spectrum disorder’ (MHSDS table MHS101). Further relevant elements of these records are the start and end dates recorded in the referral table, the records of clinical contacts (table MHS202) including the dates on which these occur, and diagnoses assigned following the referral and assessment (tables MHS604 and MHS605). Additional data relating to autism diagnosis that may be collected, includes the professional groups and occupation codes of professional staff involved (tables and MHS901) and coded standardised assessments (tables MHS606 or MHS607)

Referral rates vary widely between areas of the country, with 20% of ICB areas showing no diagnosis service activity. A further group of providers report no diagnoses of any kind made in the context of autism assessment services. A dashboard has been prepared showing currently available data for services and commissioner areas. Local services and commissioners can request access on the FutureNHS Collaboration Platform to ensure the accuracy of their data and to compare activity with other providers locally and nationally.

This approach was designed to cover the adult services described in the 2014 autism strategy. It does not cover autism assessments of children in child development or paediatric services that do not report activity through the MHSDS. Work is ongoing to identify ways to document relevant aspects of these services through the Community Services Data Set and other approaches in relation to hospital-based paediatric services.

How to commission an autism assessment service

Accountability for the commissioning of assessment services resides with the ICB, although it may transfer the commissioning responsibility to another organisation. Organisations new to commissioning with transferred responsibility may need to access support, guidance and information from organisations with more commissioning experience. We have used a model commissioning cycle to help people in commissioning roles to apply the principles of effective autism assessment services at each stage of the cycle. Figure 1 is a schematic diagram of an example of a commissioning cycle.

Figure 1. This diagram shows the continuous cycle of activity required to commission services, care and support (53).

Strategic planning

Assessing needs

To plan service capacity, each ICB will need to establish how many people from the population it covers are likely to need an autism assessment during each commissioning cycle. Population health management tools are useful for assessing need and should be used to provide good quality information with which to make informed commissioning decisions. Some considerations for assessing local demand are outlined in the following sections.

Autism assessment provision is needed throughout the lifespan

The traits that characterise autism emerge during the pre-school years, yet diagnoses given before 2 years of age are less stable than those given after this age (54). Autism is also a lifelong condition. For some people, autism is identified and diagnosed very early in life. However, autistic traits can be subtle and awareness of these is variable, meaning that for some people, traits are not identified or assessed until well into adulthood (55,56).

In each planning round, the total likely assessment need for the year ahead should be estimated alongside a breakdown of needs by age group/service type.

Autism is common; the prevalence of autism in England is estimated to be approximately 1 – 1.7% of the population (57,58). This prevalence means 1,000 – 1,700 people per 100,000 population in every age cohort is estimated to be autistic. Determining assessment capacity requires further consideration. Not everyone who is referred to or assessed by an autism assessment service will be diagnosed as autistic. In two studies, 68% and 84% of adults assessed for possible autism were diagnosed as autistic, respectively (59,60). For children and young people’s assessment services approximately 66% of children referred were diagnosed as autistic, and about 75% of those who were assessed were diagnosed as autistic (61). There are also several scenarios when somebody has an autism assessment on more than one occasion. For example, the outcome was not clear when they were first assessed or they were referred for a second opinion, so needs should also be assessed based on some people requiring more than one assessment. Therefore, to reduce wait times in accordance with national policy commitments, a minimum capacity is needed for at least 1.5 – 2.6% of the population to be referred to an autism assessment service and for at least 1.3 – 2.3% of the population to be assessed for autism.

In each planning round, the total likely assessment need for the year ahead should be estimated alongside a breakdown of needs by age group/service type

People in commissioning roles should estimate the likely need for autism assessments (including based on information about waiting lists from every service in their autism offer locality), to inform commissioning decisions. Additionally, information may be used from national autism waiting time statistics and NHS England’s dashboard to understand trends in national or neighbouring areas. Information about the range, distribution and mean wait times, as well as any differences for specific groups of people, may also be available in information used to manage contracts with services.

Furthermore, people in commissioning roles should consider historical rates of diagnosis at different ages to inform strategic decisions about the apportioning of local resource to services for autism assessment for people of different ages and with different levels of ability.

Reviewing service provisions

People in commissioning roles are expected to have accurate, current and reliable information about all providers of autism assessment services available in their area. This applies to NHS, independent, or voluntary, community and social enterprise sector organisations. Services should be reviewed with respect to the extent to which NICE clinical guidelines are applied, a Care Quality Commission (CQC) review of services has been undertaken whether services are performing well relative to national and local advisory and statutory guidance. A service self-declaring that it is compliant with NICE guidelines, or a single CQC review, is not sufficient to determine if a service is having a positive impact on the whole autism assessment offer. Additionally, owing to the lack of available evidence at the time that NICE guidelines were last updated, these do not mention telehealth assessment; therefore, providers using telehealth in autism assessment should have quality and safety checks in addition to any claims of NICE compliance.

People in commissioning roles should work with all autism assessment services and wider organisational partners to understand if any autism assessment services contributing to the autism assessment offer may have a detrimental unintended consequence elsewhere in the system. An example is when a service’s assessment decisions and diagnostic outcomes are not widely trusted by other services in the area, as this can result in services committing substantial resource re-confirming assessment decisions that, when combined with the cost of the initial assessments, represents a false economy. Another example is that if one service has narrow eligibility criteria, it may disproportionately increase the waiting times for people who meet the exclusion criteria, thereby increasing inequality.

Changes within a service should be considered in terms of its impact on the wider assessment offer. For example, expanding the remit of a service to include a period of psychoeducation, without a corresponding increase in resource, will reduce the number of assessments conducted and increase waiting times.

Reviewing service provision involves:

- Ensuring there is a full understanding of all providers from all sectors in the assessment pathway and what they can offer.

- Working with a diverse range of people with lived experience to fully understand what they want and need from an autism assessment service.

- Making sure that everyone involved in the development of an autism assessment offer is aware of gaps in provision and works together to establish how these can be addressed within the resource available.

- Working with the local authority/authorities to review market position statements and wider market development, and identifying how autism assessment services can be influenced.

It is for every ICB to determine need for its population, so as to commission and procure accordingly. ICBs are also responsible for delivering a range of other services and transformation programmes. A key element of the role of the ICB is to consider assessment of need alongside review of available service provision, and to agree how to prioritise resources so that as much as possible can be provided for the local population.

Deciding priorities

Once need has been assessed, agreeing the priorities in meeting needs with all relevant stakeholders is vital. This should involve identifying gaps in provision, for example, if there are groups of people for whom there is currently no provision, or if there are groups of people for whom the amount of provision currently available is mismatched with demand. The mutually agreed priorities should then inform the subsequent stages in the commissioning cycle.

The local authority/authorities should also be involved to make sure that any wider support is taken into consideration. This should form part of a local area’s planning on the use of personalised approaches as set out in NHS England’s guidance on personal health budgets. This may include, for example, considering if social prescribing and personal health budgets could help in the provision of pre-assessment and post-assessment support. Similarly, this could include agreeing processes for responding to requests for an assessment with a personal health budget. This process should balance the need to meet a person’s legal rights with the need to protect the autism assessment offer from negative unintended consequences, for example, untrusted assessment decisions or overwhelming services with good reputations.

Procuring services

Provision of autism assessment services could include a range of providers from the NHS, independent sector and voluntary and community sector. People in a commissioning role are expected to work across the ICS with a range of providers, including people who use services being designed. An explanatory note is available in relation to the application of the procurement, patient choice and competition regulations in the context of the new health and care arrangements, since 1 July 2022.

Designing services

The accountable ICB needs to ensure that professionals in a commissioning role work with partners so that services are designed and delivered in line with agreed priorities. This could involve re-shaping service design and delivery, or developing and procuring new services within the autism assessment offer. For example, re-shaping may be required to improve the reported experiences of the person being assessed and their family/carers, to re-distribute capacity, or to enable providers to deliver support in addition to an assessment outcome decision.

Shaping structure of supply

Once people in a commissioning role decide on what provision needs to be commissioned, they should develop clear and detailed specifications in co-production with people, family/carers and clinicians that set out precisely what is required from providers.

The autism assessment pathway is considered to have five stages, shown in Figure 2 and outlined below:

- identification and referral

- screening and triage

- pre-assessment support

- autism assessment

- post-assessment support

Planning capacity and managing demand

People in a commissioning role need to give regard to the capacity required to meet the assessed demand. This includes planning across a range of providers including NHS services, voluntary and community organisations and the independent sector. In the points below, we have provided some information that may be helpful when doing this.

Autism assessment demand capacity modelling needs to continuously plan for changing demand.

When planning capacity to meet predicted demand for an autism assessment offer, attention must be given to historical diagnostic rates of specific groups in each area to correct for historical inequalities. There has been significant variation in the prevalence of autism across sex, age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, English language fluency and geographical location (62).

There has been exponential increase in demand for autism assessment in the twenty-year period between 1998 and 2018. In this period, there has been a 787% increase in recorded prevalence of autism diagnoses in a sample of GP records in the UK (63). There was a sharp rise throughout the 1990s that appeared to plateau in the 2000s (64,65), before increasing again in the 2010s, with the most pronounced rise among females, adults and people without a co-occurring intellectual disability (63).

Plan capacity by recognising that autism assessment is time consuming.

Autism assessment capacity modelling should recognise that autism assessment, by its nature, is time intensive. One UK-based survey of autism assessment teams for children put a conservative median estimate of time required per person assessed at 13 hours of clinician time (66). Capacity modelling should also reflect that the time taken to assess for autism is variable from person to person depending on a range of factors, such as gathering information about differential or co-occurring conditions, or a person’s history. Capacity planning should therefore estimate the proportion of referrals for whom a standard or an enhanced assessment may be warranted. There should be flexibility in resource allocation such that a clinician can increase the time needed to assess a person or request input from another member of the multidisciplinary team if required.

Planning capacity for post-assessment support improves autistic people’s mental health and may reduce the amount of mental health capacity required.

Newly diagnosed autistic people and their family/carers can experience an adjustment period and may take time to come to terms with their diagnosis (19,67). Brief packages of support delivered shortly after diagnosis are found to improve autistic people’s mental health (68). Post-assessment support can help people form positive autistic identities, connect with the autistic community, and understand their diagnosis. This can also involve practical advice and sharing of high-quality information to protect people against widespread autism misinformation.

Autism assessment pathways must respect a person’s right to choose about interventions.

For a person to be diagnosed as autistic, a clinician must determine they have significant difficulties in their life. Some autistic people and some family/carers want safe and effective interventions to improve some skills and abilities that overlap with diagnostic criteria, such as language and communication (11). Some autistic people view being autistic as a positive or neutral part of their identity that does not require intervention. Pathways should be designed to respect the person’s choice in relation to intervention. Capacity should be planned with flexibility, so that it can respond to differing proportions of people seeking interventions at different times.

Assessment services must be delivered by specialist multidisciplinary teams

Assessment of autism involves consideration of differential diagnosis, whereby other possible conditions that could explain traits and difficulties presented, need to be diagnosed or ruled out. To comply with clinical guidelines, assessments must be conducted by clinical professionals who are members of a multidisciplinary team, clinicians from certain professional disciplines may conduct single clinician assessments if they judge that a consensus decision is not required (2,39). The multidisciplinary team requires the capabilities to efficiently gather information, interpret wide and varied sources of information, navigate subjective and divided interpretations, and work efficiently with other services when joint working is appropriate, such that decisions about diagnostic outcomes are consistently arrived at with a high degree of confidence. Assessment involves a degree of subjectivity, especially when a person is on the borderline of the diagnostic boundary, or when co-occurring diagnoses are present (69). Each service within an autism assessment offer needs to be confident in the diagnostic decisions made by other services. Therefore, shared specifications should be used to determine an appropriate multidisciplinary team configuration, including a protocol for which clinicians are able to make final diagnostic decisions.

Monitoring and Evaluating

Supporting patient choice

Patient choice is an important part of the NHS Constitution. This recognises the right for all patients to make informed choices about the services commissioned by the NHS and information to support decisions about these choices. In addition, Schedule 2M of the NHS Standard Contract, which is the development plan for personalised care, should be used to set out actions for people in commissioning roles or providers, to ensure that people have choice about how their autism assessment, if clinically indicated, is delivered.

People commissioning local autism services should note that they will need to:

- Provide information about the healthcare services available, locally and nationally.

- Offer easily accessible, reliable and relevant information in a form people can understand and provide support to use it.

- Set out the national determined choices available; including when there are legal rights, ensuring these are considered and built into the pathways, and are explained in NHS Choice Framework.

Managing performance

People in a commissioning role need to review and monitor the whole autism assessment market in their area in terms of how providers are performing. This should include assessing performance against current or past contracts. The clinical quality of a service should be assessed, for instance, compliance with the NICE clinical guidelines, as well as this framework and associated operational guidance. CQC regulation reports should be reviewed. For services not registered with the CQC, other sources of information should be used to determine if there is parity of regulation to CQC, and if not, a process should be determined to ensure this is communicated to prospective patients. Patient and family/carer satisfaction and value for money should also be considered.

All the above performance metrics should be appraised holistically. Prioritising a single performance metric may be at the detriment of other metrics. That is, one provider prioritising, for example, wait times could have a negative effect on, for example, adherence to clinical guidelines, quality or patient experience. This may have knock on effects elsewhere in the autism assessment offer, for example, if one provider’s decisions are routinely not trusted because of low fidelity to clinical guidelines, this can result in additional resource from other providers to review a diagnostic decision.

Seeking public and patient views

People and their family/carers have the right to provide feedback on their thoughts and experiences of accessing the autism assessment offer. There should be a regular mechanism by which feedback is reviewed and used by decision makers throughout the commissioning pathway. Table 2 outlines several ways to involve people to ensure that the autism assessment offer reflects what is needed in the area.

Table 2. Involving people and families.

| Ways to involve people and families | Resources |

| Meet as an autism strategy group to make local decisions about service provision informed by NICE guidelines, with representation from different stakeholder groups | NICE guidelines |