The National Quality Board (NQB) was established in 2009 to champion and drive strategic alignment for quality across health and care, on behalf of NHS England, the Care Quality Commission (CQC), the UK Health and Security Agency (UKHSA), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), Healthwatch England, the Health Services Safety Improvement Body (HSSIB) and the National Guardian’s Office (NGO).

This document is part of a wider suite of guidance developed by the NQB for integrated care systems (ICSs), notably: the Shared Commitment to Quality (2021); Guidance on System Quality Groups (2021) and; Guidance on Quality Risk Response and Escalation (2022). All of the NQB’s guidance is available on the webpage: NHS England » National Quality Board publications for integrated care systems

The NQB would like to specifically thank the NHS England South West Clinical Quality Team for its work in developing these principles.

Introduction

This document complements the National Quality Board’s (NQB) other guidance for integrated care systems (ICSs), and particularly the National Risk Response and Escalation Guidance which sets out how quality risks and concerns should be managed in ICSs. The document sets out key principles to use when assessing risks in environments or scenarios that are rapidly changing or based on multiple factors (e.g. multiple services/organisations involved). Whether it is unprecedented levels of pressure, unit and care home closures, new technologies, IT systems or medicines coming onto the market, pandemics or public health emergencies, health and care organisations are faced with increasing complexity.

Individual health and care organisations, including providers, Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) and Local Authorities, must ensure their approach to risk management meets recognised standards and best practice (key guidance on risk assessment in health and care includes the National Patient Safety Agency’s Risk Matrix for Risk Managers, 2008), including: agreed risk appetite statements; common language and scoring; and risk frameworks clearly linked to associated accountability and governance frameworks, which cover quality alongside wider risk frameworks (e.g. operational, financial).

However, in multi-factorial and complicated situations, collaborative approaches and whole system solutions are also required. This document has been designed to help those working in these scenarios. It does not provide detailed operational guidance on “the how”; how to develop common language and scoring, how to develop system risk appetites etc. However, it does provide a set of guiding principles, and through testing with systems we hope to provide more detailed learning on deploying the principles set out in the document.

Care quality is understood according to the NQB shared commitment’s definition, as care that is safe, effective and provides a personalised experience. This care should also be delivered in a way that is well-led, sustainable and addresses inequalities. This means that it enables equality of access, experiences and outcomes across health and care services*. Whilst developed to align with the NQB guidance, the approach also draws on Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response (EPRR) principles and can be used to support decision makers to fulfil their statutory responsibilities in planning for and responding to incidents. Annex A provides recent case studies to illustrate usage of the framework, covering mental health and ambulance services.

*The concept of high quality health and social care must take due account of requirements in relation to the Equality Act 2010 and the Public Sector Equality Duty and relevant requirements in relation to reducing health inequalities introduced by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and/or in the current Health and Care Bill. This aligns with the CQC’s 2021 strategy.

Purpose and principles

These principles sit alongside the other NQB guidance, as well as the National Oversight and Assessment Framework (OAF), the National Patient Safety Strategy and wider frameworks (e.g. EPRR, Emerging Concerns Protocol). The NQB has published a suite of guidance to help systems put in place effective leadership, culture, governance, structures and systems to manage and improve quality. This guidance has set out the expected purpose and function of System Quality Groups* and articulated the framework and mechanisms for managing and escalating quality risks and concerns, which the NQB sees as core to effective quality, including safety, management. Systems may also find it helpful to consider the four areas associated with Safety management system frameworks.

*System Quality Groups (SQGs) replaced Quality Surveillance Groups in the 2022 updated NQB guidance. All ICSs must have a SQG to bring together system partners to drive intelligence sharing and quality improvement across the ICS. Key members are: Integrated Care Boards (ICBs), Local Authorities, NHS England, CQC, primary care, local maternity systems (LMS), patient safety specialist(s) and at least two lay members, including Healthwatch.

The NQB’s framework for managing quality risks, the National quality risk response and escalation guidance, is based on an open culture and learning system, proactive and transparent intelligence sharing, system working and the need to manage risks as close to the point of care as possible. The guidance is clear that mitigation and management of risks and concerns often requires whole system approaches and solutions, involving partners from across health, social care and other services in places, systems, regions and nationally. The guidance also clarifies the mechanisms to be used to manage risk, most notably Rapid Quality Reviews and Quality Improvement Groups, alongside wider governance structures.

The NQB’s Guidance on Risk Response and Escalation is being implemented to manage risks at provider, place, system, regional and national level, however effective risk assessment and management across systems remains an area of priority, challenge and complexity. Providers and systems are having to manage significant pressures in workforce, service capacity and finances, changing population health needs, and the need to balance and share risks in multiple areas across settings.

In rapidly changing and multi-factorial situations, such as closures of care homes or mental health units, or highly pressured urgency and emergency care (UEC) departments, collaborative and dynamic approaches to risk assessment are required to decide upon the best possible or least worse course (or multiple courses) of action*.

*This approach is in line with the JESIP (Joint Emergency Services Interoperability) principles – Principles for joint working – JESIP Website.

The people, teams, services and organisations involved from across NHS, local authority and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) partners must be able to answer questions such as:

- do we have a sufficiently good understanding of the risk profile and mitigating actions within and across our organisations, pathways, services and places or are there emerging risks that are not being addressed?

- are all staff clear and sighted on the organisation and local system approach to risk sharing and what that means for individual staff and staff groups?

- how do we best work together as organisations across a place, integrated care system and Partnership to manage risks?

- how do risks across the pathway/organisations in our system aggregate and interrelate to impact on the overall summarised risk profile presented?

To answer these questions, it is important to consider risks from the perspective of different organisational/outcome lenses to understand connectivity and where resources should best be applied, and to support decision-making in rapidly changing and multi-factorial situations where collaborative solutions may be required to achieve a risk reduction across the system.

Key definitions and approaches to assessment

An overview of risk management is presented in Figure 1 below, taken from the ISO 31000 Risk Management – Guidelines (2018).

Figure 1: Overview of risk management

Image description: The image depicts the risk management process as a circular flow diagram. The main steps are:

- scope, context, criteria

- risk assessment (including identification, analysis, and evaluation)

- monitoring and review

- risk treatment

- recording and reporting

The steps are connected by arrows showing the iterative nature of the risk management cycle.

A risk is the effect of uncertainty which, should it occur, will impact either positively or negatively on those who use the service, staff, the organisation and/or the system.

Risk management can be described as a coordinated set of activities and methods that is used to direct an organisation and to control and mitigate the risk(s).

Risk assessment is the process of determining the probability of a risk occurring and the likely consequences. It is made up of three processes: risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation. Risk assessment is an iterative and collaborative process which draws on the knowledge and view of stakeholders. It should use the best available information, supplemented by further enquiry, as necessary.

Risk appetite is defined by the Institute of Risk Management as the amount of risk that an organisation or system is willing to seek or accept in the pursuit of its long-term objective. Whilst there is a standard framework for risk management, a key principle of effective risk management is the need to base is on the local risk appetite and intelligence, which will be unique to each provider, pathway or system.

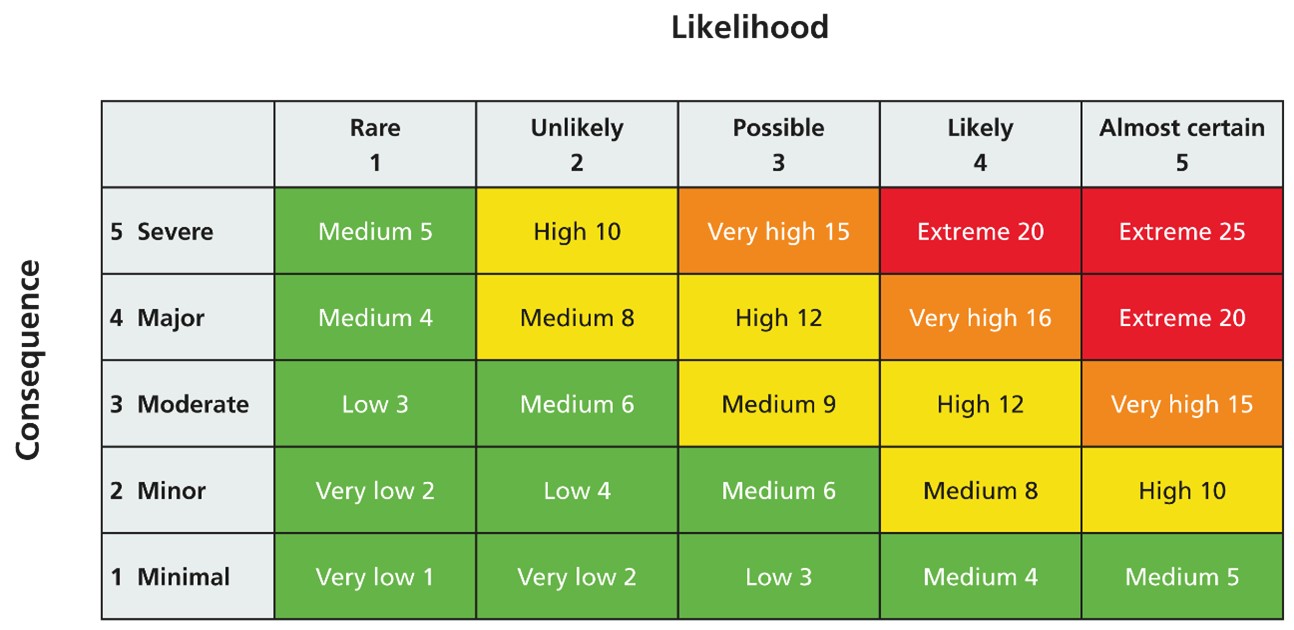

Risk assessment is common across all health and care organisations, with most organisations likely to use a matrix approach to risk recording comprised of a ‘Likelihood X Consequence’ model. Typically, risk is recorded in a format like the example below:

| Example | Consequence | Likelihood | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is a risk that….. caused by… this would lead to an impact/effect on... | 4 | 4 | 4X4= 16 |

Figure 2: A typical ‘5×5’ risk matrix

Image description: The image is a 5×5 grid depicting a risk assessment matrix. The rows represent the consequence levels from Minimal to Severe, while the columns show the likelihood levels from Rare to Almost certain.

Each cell in the matrix contains a risk score based on the combination of consequence and likelihood. The risk scores range from Very low 1 to Extreme 25.

The color-coding provides a visual indication of the risk level, with green representing lower risk, yellow for medium risk, and red for higher risk.

Risk assessment is often a pre-planned, systematic evaluation of potential risks, typically done before an activity starts and on an ongoing basis at set intervals. It identifies hazards and controls based on known conditions, and typically within single organisations. In most scenarios, existing risk processes and frameworks should be used, however in multi-factorial, fast-changing environments, there is a need for an approach that also analyses risk from the perspective of different organisations/ services and considers how risks may be shared across the system.

Key principles for assessing risks across integrated care systems

The table below sets out the types of environments and contexts to which this document applies (on the right side):

| Standard risk | Risk in multi-factorial, fast changing environments |

|---|---|

| Usually simple risks based on linear cause and effect | Reflective of a changeable set of internal/environmental states – often speculative |

| More easily predictable and therefore assessable | Less easily predictable and more complicated to assess |

| Tends to support risk trajectory from high towards low | When viewed from different perspectives; concludes a least worse/best possible option, which may not reduce all risks |

| A single risk, within the remit of a single team, department or organisation | Risk within a system or network, with recognised connectivity and contagion |

| Based on historical knowledge/patterns | Can be unpredictable and often unknown/novel conditions |

| Commonly the factors used in corporate risk assessments | Commonly associated with unknown situations or emerging information |

| Assessment requires a variation from a set of known baseline conditions.

| Requires assessment of a number of interconnecting factors (e.g. pathways, organisations, time). Determines the reasonably practicable measures to be taken. |

Examples in health and care may include:

- When a decision is made in a short time frame to close a care home or a home care agency hands back a contract. Staff in those teams may need to make quick decisions about how to provide safe, ongoing care for the people being treated by the provider, including alternative provision and/or early discharge.

- When there are unexpected medicines shortages or dispensing issues within a community, place or system, such as recent examples of ADHD medication, pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and antibiotics. Service continuity plans based on national guidance should be in place, alongside local support and services.

- In a busy emergency department (ED), a sudden rise in admissions may place unexpected pressure on paramedic and ED teams. Staff in those teams may need to make ‘on the spot’ decisions to keep people using services, families and staff at lowest risk – be it diverting ambulances, opening up temporary escalation spaces or increasing early discharge. The OPEL (Operating Pressure Escalation Level) framework can help teams decide what actions and escalations are needed to manage risks, however they need to be viewed collectively and dynamically.

Other examples include a public emergency (e.g. large fire) or the withdrawal of medication from the market. In these cases, there will be a need for teams to make rapid decisions that involve multiple perspectives and partners. The risk profile in one or more organisations may need revising, or there may be a need to share risk across the system in order to achieve a decision that is least worse, best possible or for the ‘greater good’. Who will own and manage the shared risks? How will the response be coordinated and who will monitor it? What changes are needed?

In order to answer these questions, those involved must follow a number of key principles. These principles cover culture, systems, structures, policy and support, all of which are needed for effective risk assessment and management.

- Person-centred: Actively focus on the experience of people using services, carers, family, staff, students and learners, across all risk management activities. What does quality, including safety, look like from their perspective? What are the key concerns and risks? How are we using feedback from these groups to assess, mitigate, manage and monitor risks?

- Collaboration and engagement: Across places, pathways and systems, involving all key organisations, services, and teams, from across health, social care and wider services. The collaboration should be in line with the system strategy (e.g. ICP Strategy, Joint Strategic Needs Assessments (JSNA)), NQB Quality Risk Response and Escalation Guidance and wider policy (e.g. EPRR policy, OPEL framework, Better Care Fund plans, annual safeguarding reports). This ensures that a comprehensive understanding of risks is achieved and that the best possible strategies are co-developed.

- Open and proactive intelligence sharing: Key to successful assessment and decision-making, this means being able to answer questions such as: what data/information are we using across the system to assess the risks? Where are we getting this information from and are there gaps? Are there any cultural issues getting in the way of intelligence sharing?

- Common risk profile, language and scoring: It is key that the services and organisations involved have a common risk profile, language and scoring, against which shared risk appetite levels should be set. This requires using consistent risk matrixes and, if possible, agreed thresholds for levels of risk defined by reference to common, objective measures.

- Clear roles and coordination of responsibilities: All relevant teams and organisations must be clear on roles, responsibilities and accountabilities, including:

- who is responsible for monitoring, reviewing and updating the information and assessment?

- who will ensure that resources are identified and coordinated to support improvement?

Processes fail when there is no accountability to deliver and no mechanism to coordinate and assure, which is where the system role is important. Ensuring that accountability lines are clearly defined and communicated to everyone involved, including timescales and ongoing maintenance, is a priority. The ICB’s role in providing objective challenge on risk assessments for health should also be recognised.

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) across system partners may be helpful. The role of System Quality Groups in coordinating improvement and risk management should also be understood and agreed, as well as System Coordination Centres for health.

- Clear reporting, recording and monitoring:

- As above, a shared risk appetite should be in place. The ‘weighting’ of some areas of impact may be considered greater than others, which should be clearly documented.

- The outcomes of the assessment should be recorded alongside jointly agreed priorities and improvement plans. The documentation should include a recording of time to provide an audit trail, as the assessment may need updating over a period of time.

- The individual Boards in all relevant system organisations, including Integrated Care Boards and Local Authorities, must have visibility of assessment and outcomes, including being notified of any actions that may increase risk share in a part of the pathway/ system or that deviate from national policy and standards (with clear justification as to why and a timeframe). The CQC should also be informed of any actions that increase risk and how they were agreed.

- Board assurance frameworks of all relevant organisations should be populated to include the decisions.

- Effective action planning and mitigation: Goals should be SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Time-based), with clear information on timelines, action holders and inter-dependencies, aligned to accountability frameworks.

- Escalation: where quality risks cannot be managed at system level, they should be escalated to NHS England regions in alignment with the National Quality Board guidance or via alternative required routes (e.g. Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response Process, local authority or safeguarding governance).

- Competent decision-making: A distinguishing feature is the need for competent decision-makers who can judge risks in real-time and through a system lens. This requires training, communication and support to recognise potential threats, understand their implications and make crucial decisions swiftly and effectively within a wider learning system.

- Equalities and inequalities: A focus on equalities and inequalities should underpin the assessment and response. Are particular population groups at higher risk or more likely to receive an adverse impact from the mitigations/management? Are there gaps in insight from an equality and diversity perspective?

- External factors consideration: Consider external factors such as regulatory changes, technological advancements and public health trends that can impact care and outcomes.

- Dynamic and regular review: Dynamic and regular review and monitoring is needed to adjust strategies and interventions to mitigate potential risks. Organisations and systems must also learn from past incidents, as well as where things have gone well, to refine their processes.

Assessing risks in practice

This document sets out the need to review how risk management is implemented in fast-changing and multi-factorial environments, and the key principles to support this approach. In working with systems, we intend to develop more detailed understanding of how to apply these principles and frameworks, including the role of ICBs vis-à-vis wider system partners. Below, we set out a first step in terms of how risk matrixes can be updated to be used in integrated care systems. Further examples are provided in Annex A.

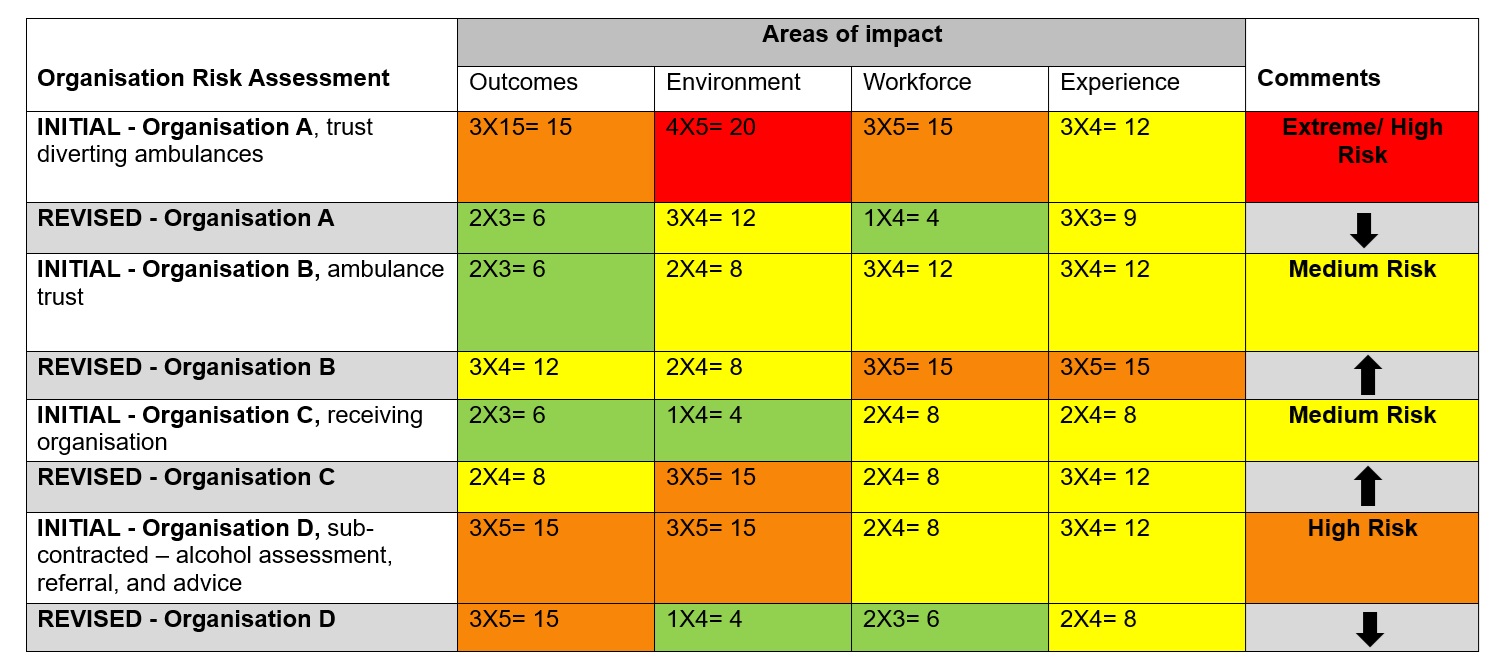

The example in Figure 3 below has been system tested when developing these principles and refers to significant pressure in the urgent and emergency care pathway, and assessment as to whether ambulances should be diverted to another provider. In the example:

- The dimensions of assessment – risks and areas of impact – have been identified, agreed and articulated by the different organisations in the system. They will vary according to local circumstances. Risks might cover parts of a service, pathway or system. Areas of impact might include quality (e.g. safety, experience), inequalities, performance (e.g. access, treatment times), finance, workforce (e.g. capacity, morale, training programmes, placements), environmental, or be aligned to the taxonomy used in the SEIPS framework (i.e. technology/tools/equipment; people/persons; tasks; physical environment; organisation; and external environment/context).

- The changes to the assessment post-intervention have been clearly articulated. The re-assessment and reporting should be undertaken regularly, and the least worse scenario maintained for as short a period as possible.

Scenario: Decision to divert ambulances from one organisation due to exceptional pressures within the Emergency Department.

Figure 3: Example of risk assessment across an integrated care system

Image description: The image is a risk assessment matrix that evaluates various organisational entities across different areas of impact. The risk scores range from 4 to 25, with color-coding to indicate low (green), medium (yellow), and high (red) risk levels.

The matrix shows the initial risk assessment for Organisation A, which had an “extreme/high risk” rating. The revised assessment for Organisation A reduced the risk to “medium.”

For Organisation B, the initial and revised assessments both indicated “medium risk.” Organisation C also had a “medium risk” rating in both the initial and revised assessments.

The initial assessment for Organisation D, which involves sub-contracted alcohol assessment, referral, and advice, resulted in a “high risk” rating. The revised assessment for Organisation D is not shown.

In the example:

- for the trust diverting ambulances (org A) the decision to divert ambulances may result in reduced pressure and therefore reductions in patient harm (outcomes), environmental risks (trips, falls etc. associated with overcrowding), workforce (human factors), as well as improvements in experience of care

- however, the ambulance trust (org B) may experience increased risks to patient harm (outcomes) and experience due to travelling larger distances to convey patients to hospital, therefore increasing their response times

- the organisation receiving diverted ambulances (org C) may be under pressure and hence see increased risks to outcomes, environment workforce and experience

- the sub-contracted organisation offering alcohol assessment, referral and advice (org D), working out of the ED that is diverting the ambulances, may also see a reduction in risks to environment, workforce, and experience. However there may not be a service within the receiving trust and therefore care outcomes may be impacted

The example illustrates how assessment through a system lens opens up new mitigations/ interventions based on least worse/best possible scenarios, but also the need to continue assessing dynamically to mitigate the risks as best as possible. The example could be broadened to assess risks in other parts of the system. For example, the decision to divert ambulances may make it harder for discharge teams at organisation C to discharge people and may mean that the person being discharged may consequently require more community, social care and primary care support.

Conclusion

As risk management within health and care continues to mature, it has become more important than ever to ensure that risk assessment is effective, systems-based and responsive. The organisations involved in delivering and commissioning health and care must ensure that their risk frameworks and processes are being used effectively in line with key standards, and that those assessing risks have the skills and capabilities needed to do this effectively. At the same time, there is also a need to consider the role of a collaborative approach to risk assessment in today’s operating environment: one that recognises that different organisations and system partners must not only understand each other’s key risks and priorities, but also support each other to manage them. The NQB hopes that the principles set out in this document provide a useful reference and starting point to those assessing and managing risks across integrated care systems.

Annex A: Case studies

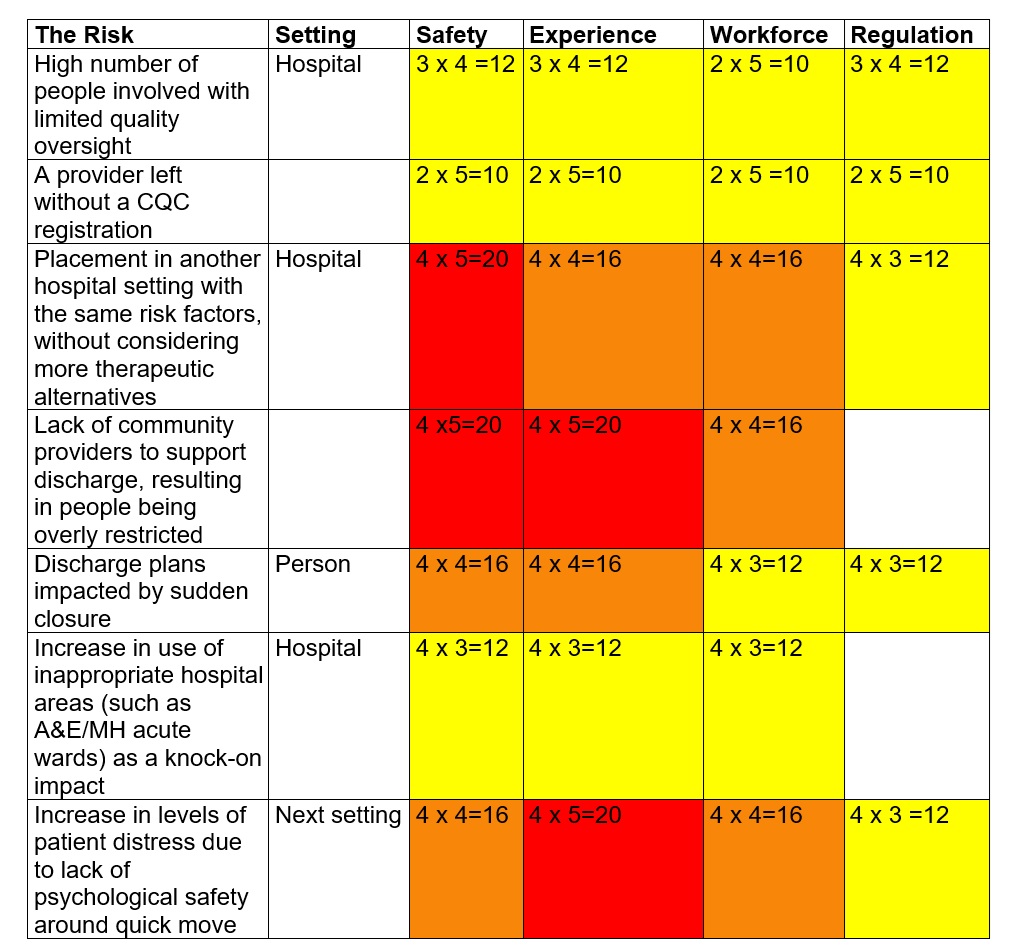

Case study 1 – closure of an independent mental health unit

Scenario: Decision to close an independent hospital due to quality concerns raised by the CQC and removal of the provider’s registration within a short time frame (such as 28 days closure).

The problem

- many years of the provider being in and out of “special measures” with CQC

- a high number of commissioners using the service to place people far from home* (e.g. 22 different ICB’s for 80 people)

- the ICB in which the hospital service is located does not use this provider, and therefore does not have clear oversight of the service

- limited quality oversight from placing commissioners for people without a learning disability and autism diagnosis

- a large number of community providers in the placing ICB with different approaches to managing people on their caseload

- lack of specialism despite being a specialist service, and a lack of a clear clinical model*

- long lengths of stay for all inpatients*

- high levels of distress in patients being managed in non-local environments

- above average physical health concerns for inpatients

- patients are frequently described as ‘hard to place’ by commissioners and hypothesis is this is leading to acceptance of standard of care

- high levels of restrictive practices are noted*

- provider has low levels of safeguarding which doesn’t reflect clinical activity, and safeguarding concerns are completed retrospectively by provider

- above average staff turnover and recruitment

- above average staff sickness

- high levels of agency use

- constant key changes to the senior leadership team

- financial constraints of the provider due to CQC restrictions resulting in no new admissions into the service

- the hospital is not physically near other services and therefore is isolated from system support and visitor footfall*

- Higher Education Institution (HEI) healthcare training programmes impacted with sudden loss of available clinical placements including for mental health students and trainees currently on placement at the Trust

*Known risk factors for closed cultures in mental health hospitals, which can lead to breaches of people’s human rights, including patient abuse.

Image description: The image is a 5×5 risk assessment matrix that evaluates various risk factors across areas like setting, safety, experience, workforce, and regulation. Each risk factor is assigned a numerical risk score ranging from 4 to 20, with color-coding to indicate low, medium, and high risk levels.

The matrix provides a structured way to assess and compare different risk factors across the key impact areas for this organisation.

Improvement plan

- lived experience representation across the system response infrastructure

- placing ICB’s review the models of care they are commissioning and align to the evidence base

- placing ICBs still reliant on out of area placements take a more assertive role in quality oversight where people are moved to a different hospital setting

- ICB in which the hospital is located takes a proactive approach in working with stakeholders to co-ordinate the closure

- the patient and families are at the heart of the response when closing, making sure their voices are heard with effective use of advocacy, utilising approaches such as Peer advocacy

- safeguarding alerts are raised as soon as they are identified, and the workforce understand safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility

- the ICB is aware of their people and therefore have a clear plan to bring people nearer to home. This involves the ICB having a clear grip on up-to-date information

- ICB and NHS England Regions work with HEIs to urgently seek alternative placements for current healthcare students and explore requirements for future alternative high quality education clinical placement locations

- primary and urgent focus remains on understanding patient needs, experience of care and treatment, and discharge pathways

Staff experience

- acknowledge suboptimal circumstances

- hold honest conversations

- visible leadership

- reduced duplication of non-value adding tasks

- non-urgent activity and training temporarily paused to support the response

- thanks and praise for action taken where it is putting the patient at the heart of decision making

Quality measures

- patient voice at the centre of closure support

- weekly review of incidents – with incidents related to boarding, double occupancy, operational flow forwarded to the Chief Nursing Officer/ICB/Region

- weekly review of complaints / compliments and concerns

- weekly review of PALS

- monthly – Friends and Family Test review

- regular contact and feedback from staff of all grades and disciplines

- monthly review of Freedom to Speak Up Case data

- reduction in length of stay

Governance

- The Provider Board

- Integrated Care System in which the provider is located, including System Quality Group

- Placing ICBs

- CQC

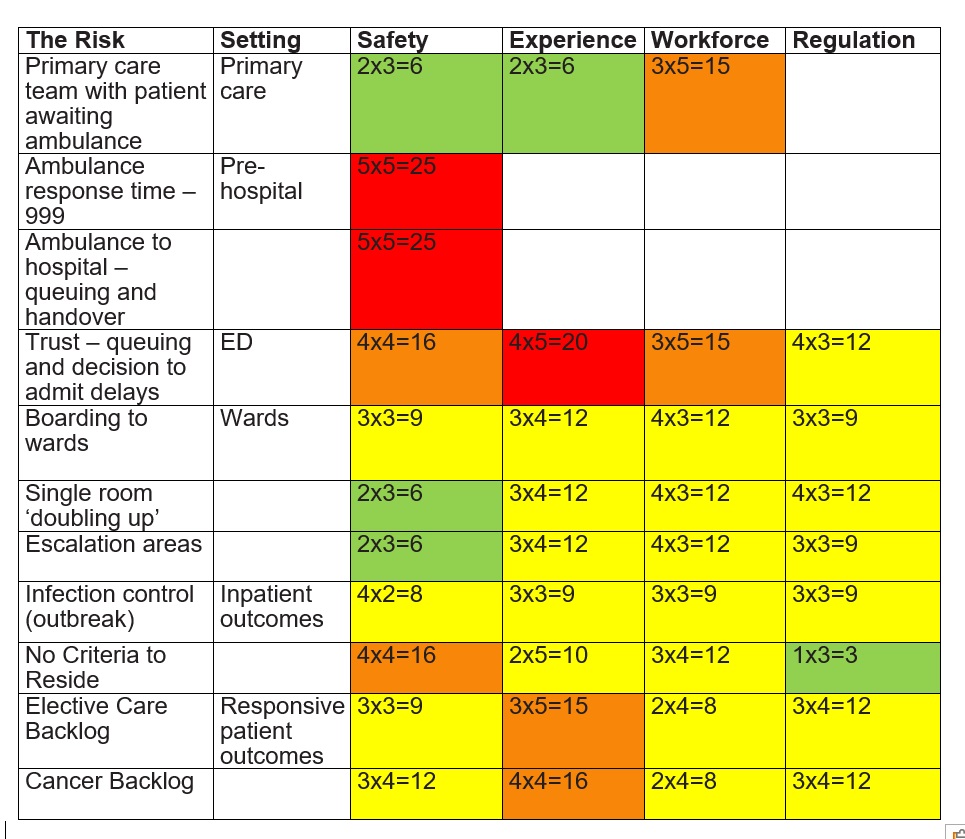

Case study 2 – improving ambulance handover delays

The problem

- community safety risk with Ambulance Trust

- primary care team pressures to stay with people awaiting ambulances

- average 14 ambulances a day would queue over 4 hours

- average longest ambulance handover time – nearly 10 hours

- average ambulance resource hours lost per day – 139 hours

- category one mean response time – 11 minutes

- average Emergency Department (ED) length of stay 13 hours (medicine)

- average Decision to Admit (DTA) at 7am – 24 hours

- average 12-hour breaches per day – 14

- discharge activity disproportionately later in the day

- 70 escalation beds/spaces open

- infection control/COVID beds closed – 10

- Friends and Family Test – 21% negative

The risk assessment

- highest risks relate to ambulance response times, conveyancing and admission delays

- lowest risks relate to single room doubling up, escalation areas and infection controls

Image description:

The image is a 5×5 risk assessment matrix that evaluates various risks across different areas including setting, safety, experience, workforce, and regulation. Each risk factor is assigned a numerical risk score ranging from 4 to 20, with color-coding to indicate low, medium, and high risk levels.

The risk assessment matrix provides detailed risk scores for various factors like primary care team with patient awaiting ambulance, ambulance response time, ambulance to hospital queuing and handover, trust decision to admit delays, boarding to wards, infection control, and more. The matrix allows for a structured evaluation of risks across multiple organisational areas.

Action plan

- Early discharge (home or discharge lounge) before midday for pathway zero patients.

- Ambulances must not queue for longer than 15 minutes, in line with national guidance

- One patient moved from ED to Acute Medical Unit (AMU) every hour and one patient to Acute Frailty Unit (AFU) every two hours continuously over the 24-hour period.

- Every hour between 0800 and 2000, two patients from AMU and one patient from AFU will be transferred to the wards.

- By 2200 every evening AMU should ensure that there are ten empty beds and AFU should have five empty beds.

Staff experience

- Acknowledge suboptimal circumstances

- Honest conversations

- Reduced duplication of nursing assessments and non-value adding tasks

- Pause/slow appraisals and mandatory training completion

- Thanks and praise.

Quality measures

- Weekly review of incidents – incidents related to boarding, double occupancy, operational flow forwarded to the Chief Nursing Officer

- Weekly review of complaints / compliments and concerns

- Weekly review of safeguarding concerns

- Weekly review of PALS

- Monthly – Friends and Family Test, including qualitative feedback themes

- Regular contact and feedback from staff and volunteers (all professions and grades)

- Monthly review of Freedom to Speak Up Case data.

Governance

- The Board

- Integrated care system

- System Quality Group

- CQC

Publications reference: PRN01589