Summary

Clinical academics combine clinical work in the NHS* with research and provide the bridge between the two; they take insights from clinical practice to inform research and translate research findings into innovations to improve care for NHS patients. Clinical academics are crucial to training future generations of healthcare professionals, by leading on research and delivering much of the teaching of students (NHS England 2023). Yet we know the pharmacy workforce are underrepresented among clinical staff who take up clinical research training opportunities; for example, only 137 of 5,000 applications to the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) doctoral fellowship between 2014 and 2021 were from pharmacy professionals, and of these only 23 were successful (NIHR, 2017).

* The NHS refers to NHS England, NHS Scotland, NHS Wales and HSC Northern Ireland.

The NHS England Office of the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer led a short-life working group (SLWG) to make initial recommendations around a delivery model and framework for developing a clinical academic pharmacy workforce, applying the recommendations and experiences from the report Medically and dentally qualified academic staff: Recommendations for training the researchers and educators of the future to pharmacy. They were informed by a UK-wide call for evidence on clinical academic careers in pharmacy, launched in May 2022.

This report presents the findings of that survey and makes recommendations for the short, medium and long term, to inform the next stages of the programme to create a clinical academic career pathway for pharmacy. These will be the basis for a pharmacy work plan working in collaboration with the NIHR pharmacy professionals incubator. They support the embedding of research at all stages of a pharmacy professional’s career as well as the provision of a pipeline of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who will become research leaders.

Main findings

Only a minority of the pharmacy workforce are currently research active. Protected time and support, both at the individual and organisational levels, are the most significant enablers for promoting the pharmacy workforce involvement in research and fostering clinical academic pharmacy careers. Barriers align with these enablers, emphasising the need for funding, including capacity building and ongoing posts. Details of survey responses supporting this overview can be found below:

- Among individual respondents, data collection, data analysis and publications were the most commonly reported research activities, and among organisational respondents the most common research activity was support for individuals to participate in or lead research as principal or co-principal investigators.

- Three-quarters of individual respondents had not applied for research training funding and of those who had, this was mostly for a NIHR doctoral fellowship or a Pharmacy Research UK (PRUK) award.

- Just under a quarter of individual survey respondents had applied for an NIHR or other research project grant, and just under half of the organisational survey respondents had supported individuals to apply for such a grant.

- Among individual respondents the most frequently perceived enablers to undertake research were protected time, support from employing organisations, funding, support for making an application and joint projects between the NHS and a university. Among organisational respondents these were funding for grants and research projects, joint research projects between employers and universities, named contacts to support aspiring researchers and jointly funded posts such as between the NHS and a university.

- Among individual respondents the most frequently perceived barriers to research training and capacity building were lack of protected time, no/limited support from employing organisations and lack of funding. Organisations perceived lack of funding to build research capacity and for joint funded posts as the key barriers.

- Overall protected time and support, mentoring and awareness of research training opportunities were identified as key to research capability and capacity building amongst pharmacy professionals.

Recommendations

The recommendations are for all the UK devolved nations, and are categorised by identified issue (research training, mentoring, engagement and protected time) and whether short (implemented by end of 2024), medium (end of 2026) or long term (end of 2030). These recommendations support the embedding of research at all stages of a pharmacy professional’s career, as well as the provision of a pipeline of pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who will become pharmacy leaders.

While these recommendations were developed to be as inclusive as possible, it is recognised that the pace and order of implementation may vary across the devolved administrations, to suit the national context.

Background

Clinical academics – within medicine, nursing, midwifery and other professional groups – work across healthcare providers and academic institutions, combining clinical work in the NHS with research and/or teaching activities. They provide a bridge between the two; insights from clinical practice inform research, and innovation and research can rapidly be translated into improving care for NHS patients.The 2023 NHS Long Term Workforce Plan highlights the importance of these careers within all professional groups and the need to increase their number, and the Royal College of Physician and NIHR joint position statement in 2022 sets out recommendations for making research part of everyday practice for all clinicians.

The NIHR has offered clinical research training opportunities to pharmacists and allied healthcare professionals since 2008. However, in 2017, a NIHR strategic review of training found that most trainees were medical, and pharmacy was an under-represented discipline. Only 137 of 5,000 applications to the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) doctoral fellowship between 2014 and 2021 were from pharmacy professionals, and of these only 23 were successful.

The Interim NHS People Plan recommended “clinical pharmacists in all sectors will increase their activity in clinical research”.

The pharmacy professions must proactively support research and enable some individuals to become research leaders with a clinical academic career pathway – as other professions are doing. In November 2021 the Chief Nursing Officer for England published her strategic plan for research: Making research matter, and in in January 2022 the Chief Allied Health Professional Officer for England published the Allied health professions’ research and innovation strategy for England. Currently there is no equivalent plan for pharmacy professionals.

The General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) has defined standards for initial education and training (IET) for pharmacists that encompass the Master of Pharmacy (MPharm) degree and a fifth year of training, known as the Foundation Year. The reformed GPhC IET for pharmacists due to be reviewed in 2023, contains five domains one of which is education and research and research criteria are implied in the APTUK national competency framework.

The UK Government’s independent report, Commercial clinical trials in the UK in May 2023, highlights the decline in industry-funded research in the UK. In the period 2017/8 to 2021/22 the number of people recruited to industry clinical trials nearly halved. This represents a threat to patients’ access to innovative treatments, the NHS and the UK economy. Given the historical central role of pharmacists in the medicine supply chain and increasingly as decision-makers and prescribers, the pharmacy professions are well placed to be the lynch pin in supporting the delivery of clinical research and clinical trials. However, for this to happen they need to be trained in the fundamentals of research and to be research ready. The contribution of community pharmacists in recruiting participants for Covid-related studies, such as the PRINCIPLE trial and the PANORAMIC trial, showed the professions’ willingness to take part in research studies. This is an excellent foundation on which to build, but looking to the future pharmacy professionals should be taking a leading role in the delivery of these studies, and be doing more than recruiting participants.

Developing initial recommendations for a clinical academic career pathway for pharmacy

A short life working group (SLWG) was established in late 2021 to advise on proposals for an initial delivery model and framework for developing a clinical academic pharmacy workforce, applying the recommendations and experiences from the report: Medically and dentally qualified academic staff: Recommendations for training the researchers and educators of the future. The NHS England Office of the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer led the SLWG and the group included representation from clinical academics, academics, Association of Pharmacy Technicians UK (APTUK), GhPC, NHS England Workforce Training and Education (previously Health Education England), NIHR, Pharmacy Schools Council, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) and the Chief Pharmaceutical Officers from the devolved administrations.

The group’s recommendations (see Summary above) are based on evidence from the online survey described below, and learning from other professional groups. They support the delivery of the objectives of the SLWG which were to:

- Facilitate the adoption and spread of a research culture across the pharmacy professions through raising awareness of clinical academic careers.

- Increase research capability, capacity and leadership, through structured and protected pathways, starting with enhanced research training offers from the foundation year.

- Help pharmacy professionals, starting with pharmacists, gain better access to existing research training opportunities and research/educational awards through co-ordination of information, support for effective networking and mentorship.

- Propose new forms of support and professional development opportunities for pharmacy professionals, starting with pharmacists in research and academic education with identified potential funding streams, building on pilot initiatives.

Online survey

NHS England launched two surveys in May 2022, one for individual pharmacy professionals and one for organisations. These comprised 50 and 41 questions respectively. Most of the questions had a fixed choice response mode or Likert type scale response, but some sought open text responses, and filter questions probed some areas.

The Pharmacy Schools Council hosted the surveys online, on behalf of NHS England, and the surveys were extensively promoted through a webinar, presentations, social media and targeted communications. There were 218 evaluable responses from pharmacy professionals (188 (86%) pharmacists and 30 (14%) pharmacy technicians) and 41 from organisations.

Most respondents were from NHS trusts (eg hospitals) or higher education institutions (HEIs) in England. Most individual respondents identified as female and of white ethnicity (see Tables 1 and 2 in Appendix 1).

These surveys are the first to map clinical academic pharmacy research experience across the UK. With no defined clinical academic pharmacy population, or even a known population of pharmacy professionals engaged in any level of research activity, it is difficult to establish how representative our respondents are of the professions, but we do note the underrepresentation from the devolved nations and community pharmacy. Despite these limitations, our findings do corroborate the recent literature, both from the UK and internationally, on why pharmacy professionals do not take part in research (Reali et al, 2021).

The following section describes our quantitative and qualitative findings; detailed data tables and figures mentioned in the text are provided in Appendix 1.

Findings

Research capacity and capability in the pharmacy professions

Research activity and experiences

Most pharmacy professional research activity involves participation and/or publication, not research leadership.

For individuals, the most frequently reported research activity was data collection (67% (146/218)), followed by data analysis (62% (136/218)) and publication (64% (140/218)), of which 95% (133/140) was publication in peer reviewed academic journals.

Most organisations supported individuals to participate in or lead research as principal or co-principal investigators (66% (27/41)) and to publish (66% (27/41)), as opposed to supporting individuals to secure research grants (32% (13/41)) (see Table 3).

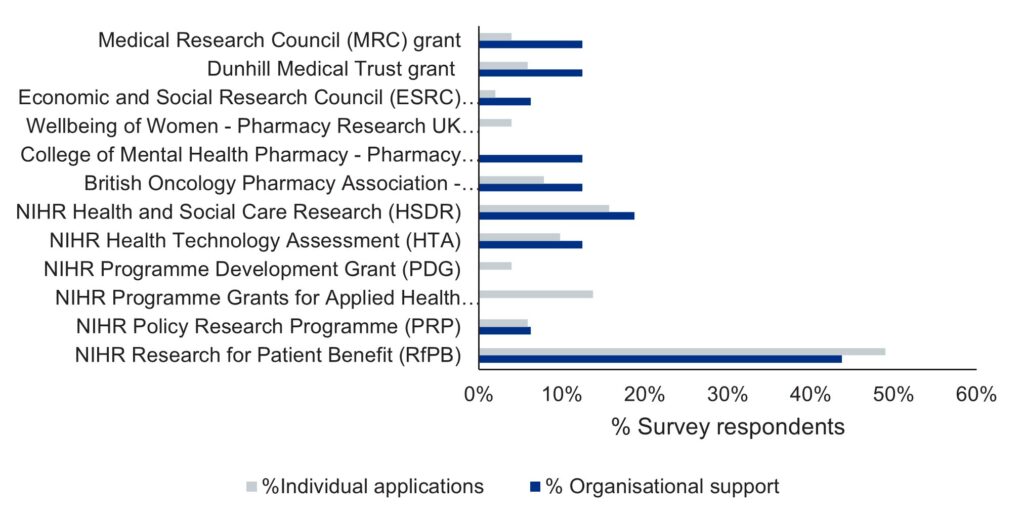

Nearly a quarter (23% (51/218)) of individual survey respondents had applied for an NIHR or other research project grant and 39% (16/41) of organisational survey respondents supported individuals to apply for any NIHR or other research project grant (see Figure 1).

Formal research training and education

Three-quarters (75% (164/218)) of individual respondents had never applied for research training funding. Of those who had, this was mostly for either an NIHR doctoral fellowship (20) or PRUK training bursary (11), and 41% (22/54) were successful (see Table 4).

Nearly three-quarters (73% (30/41)) of the organisational survey respondents reported that they supported individuals to apply for research training awards, and 63% (19/30) had a named lead with responsibility for pharmacy professionals undertaking postgraduate research training, although 40% (12/30) stated they did not or were unaware of a named point of contact for funders (see Table 4).

Engagement with NIHR infrastructure

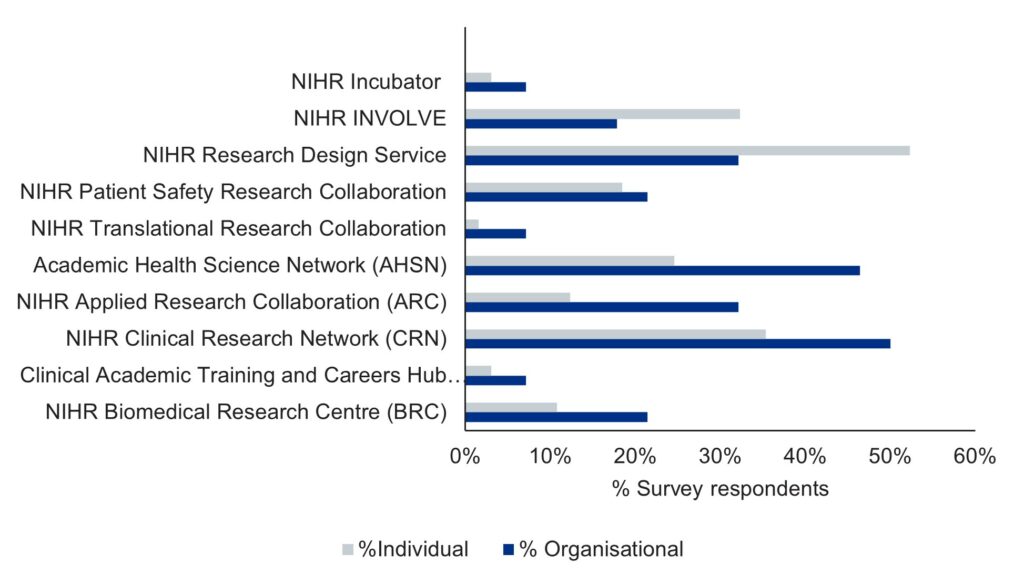

Only 30% (65/215) of individual respondents had engaged with the NIHR, NIHR Research Design Service, NIHR INVOLVE or an Academic Health Science Network (AHSN; now renamed Health Innovation Network).

Organisational responses followed a similar pattern, but engagement with clinical research networks was most frequently reported (68% (28/41)) followed by an AHSN and then the NIHR Research Design Service. There was low engagement with existing NIHR incubators, the Clinical Academic Training and Careers Hub (CATCH) and the NIHR Translational Research Collaboration (see Figure 2).

Enablers and barriers to clinical academic pharmacy careers

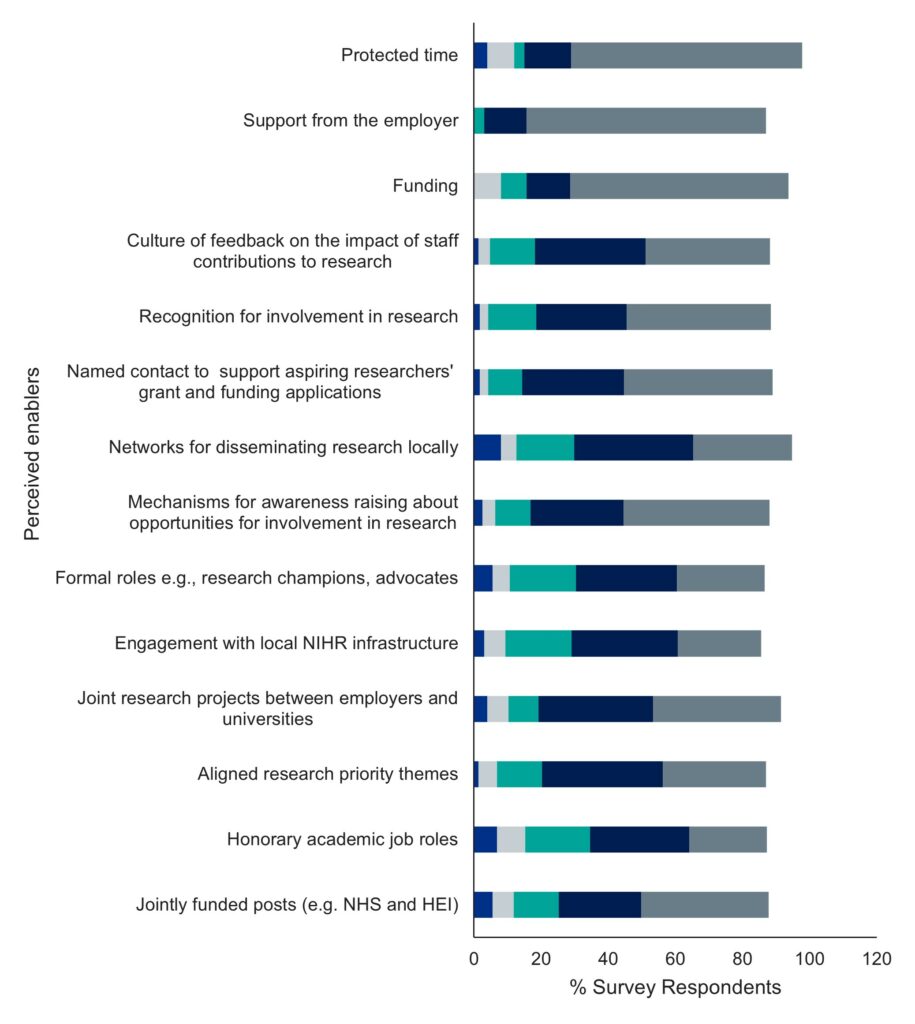

From the survey quantitative responses, the main enablers reported by individuals were protected time, support from employing organisations, funding, support for making an application and joint projects between the NHS and a university (see Figure 3).

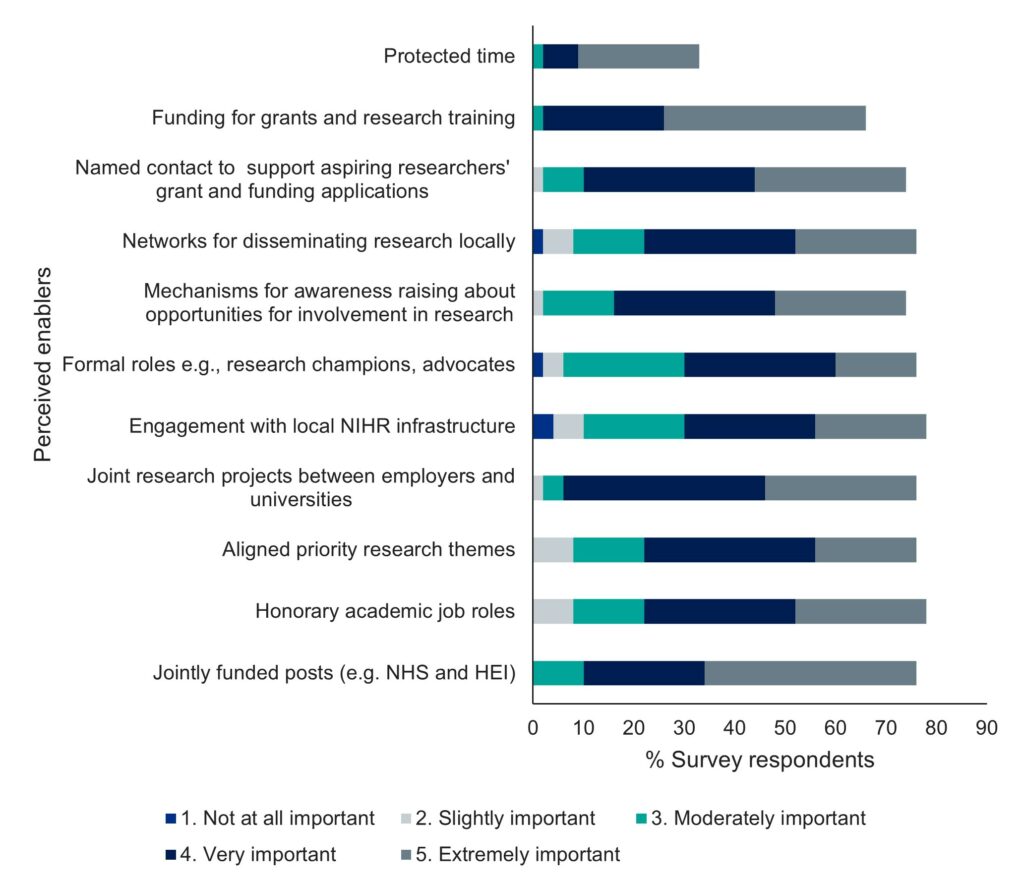

For organisations these were funding for grants and research projects and joint research projects between employers and universities, named contacts to support aspiring researchers and jointly funded posts such as between the NHS and a university (see Figure 4).

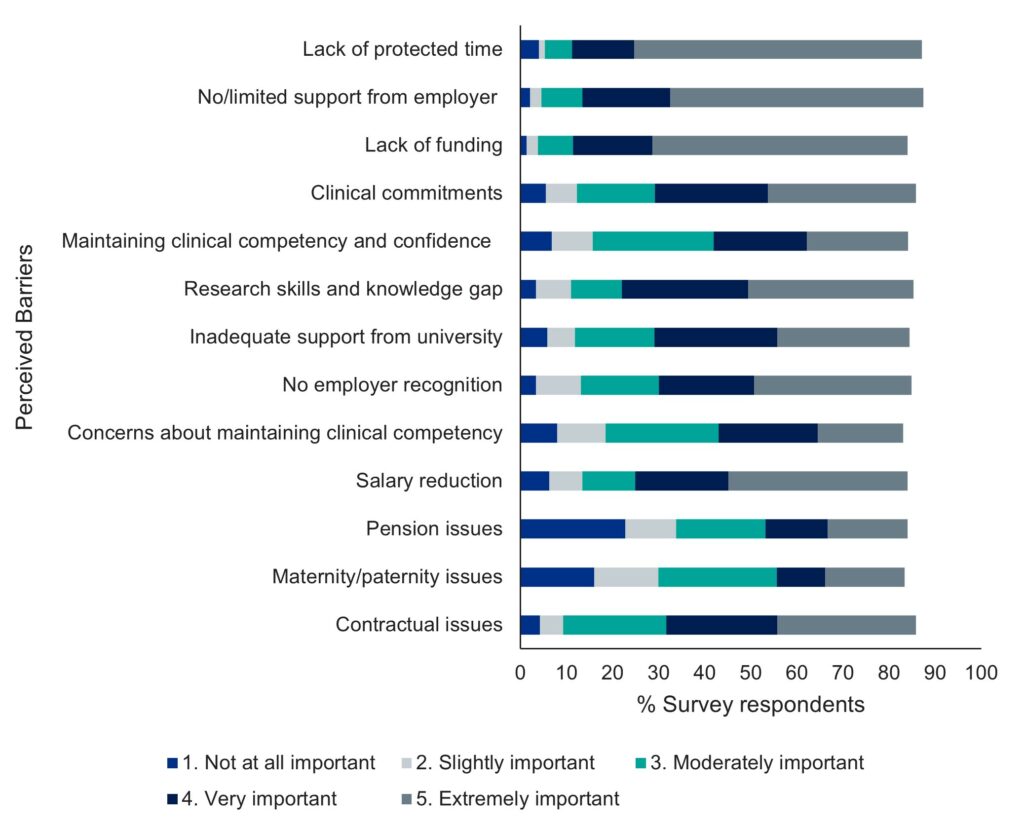

From the survey quantitative responses the main barriers to research training and capacity building reported by individuals were lack of protected time, no/limited support from employing organisations and lack of funding (see Figure 5).

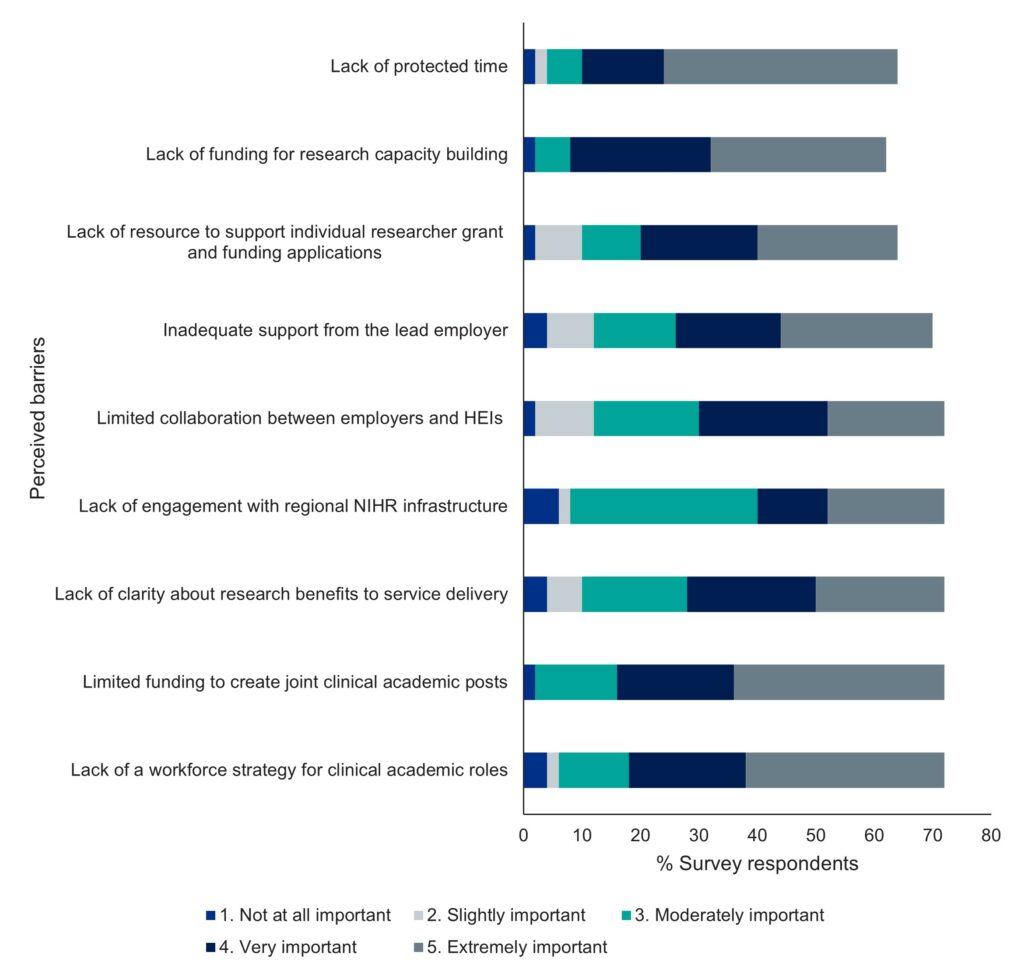

For organisations the main barriers were a lack of funding for research capacity building and for joint funded posts. Other noted barriers were lack of protected time and of a workforce strategy that recognised clinical academic career pathways (see Figure 6).

Associations between indicators of research activity and enablers

Using the Chi-square test with statistical significance set at ≤0.05 there is a significant association between all the positive indicators of research activity and all the perceived enablers, other than between attaining a research degree and having a named lead responsible for clinical academic pharmacy professionals.

| Indicators of clinical academic practitioner research activity | |||||

| Research degree | Grant applications in the past 5 years | Individual award applications in the past 5 years | Clinical academic appointment | ||

| Enablers | Protected time for research | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association |

| Mentorship | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association | p <0.001 Significant association | |

| Named lead responsible for clinical academic pharmacy professionals | p = 0.3 Not significant | p <0.05 Significant association | p <0.05 Significant association | p <0.05 Significant association | |

The survey provides limited evidence that pharmacy professionals are more research active when the key enablers of protected time for research and support for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are in place. Such support is required at an individual level from mentors and leads within the employing organisation responsible for research, but also more generally. Not surprisingly the perceived barriers mirrored these enablers, but organisational respondents also emphasised the need for funding, for both capacity building and ongoing posts, as well as a revised workforce strategy that recognises a clinical academic career pathway.

The free text responses from a subset of responders included examples of how these enablers could be implemented. These are summarised and discussed in context in the sections below. Appendix 2 provides selected examples of organisational actions taken to increase capability and capacity in the pharmacy professions.

Protected time, jointly funded posts and funding

Several individual respondents considered that protected time, potentially enabled through job plans, should be available for preparing grant applications, and for undertaking research.

Similarly, some individual respondents felt that employer support should include backfill, adequate remuneration for research, official post-holding at an academic institution, support with applications, access to appropriate supervisors and protected time for research training and grant applications; and that jointly funded posts should align with professional goals or the field of work objectives.

Comments from some organisational respondents suggested the need for a standard pay scale and pension plan between academia and the NHS. Individual responders noted that a reduction in salary when moving from a clinical to an academic role would be a barrier.

In many ways protected time and funding are inextricably linked. Protected time would be achieved through specific research posts – both at the introductory capacity building level and for more long-term leadership roles, and/or through job plans incorporating research time. Both require additional funding as if job plans allow time for research, more clinical posts will be needed to maintain the delivery of patient care. This will require a revised workforce strategy and review of current workforce planning in addition to the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan.

Clinical academic pathway for pharmacy professionals

Comments from both individual and organisational respondents considered that clinical academic practitioner roles must be part of a career pathway so that individuals can see a route to progression, and suggested that specific roles linked to schools of pharmacy are required. Some felt two levels are required: one for those in training, where teaching and research forms part of their clinical experience and building research activity into the day-to-day working of pharmacy professionals; and one for those who are clinically active in the NHS but also contribute to formal teaching programmes or research at a HEI.

The new RPS frameworks, which all include a specific research domain, should be universally embedded across pharmacy careers, from the undergraduate through to postgraduate years, and linked to career progression.

In early 2021 the NIHR launched a competitive tender seeking applications from organisations for programmes to develop an e-learning introductory research course. The RPS was the first to be successful and its course went live in early 2023. The course particularly supports those pharmacy professionals seeking to fulfil the criteria to achieve the research domains in the RPS curricula (research and evaluation, credentialing) and those implied in the APTUK competency framework.

Absence of a research culture

Individual and organisational respondents identified a culture of working as sole practitioners, with limited ‘bedside’ learning that prompts ideas for research and multidisciplinary discussions, as a barrier to developing a research culture. In addition, individuals reported that the culture within departments limiting autonomy among pharmacy staff was a barrier to engaging with research activities. Without parity of a research culture with other clinical disciplines, pharmacy finds it harder to attract research funding. One organisation with good research infrastructure reported it struggled to attract and encourage pharmacy staff to take part in research, and another reported that research success is often seen as an individual accolade rather than a departmental success. It was also reported that pharmacy technicians find it more difficult to undertake research, as research is not explicitly aligned with current learning outcomes and frameworks.

In 2022 the General Medical Council (GMC) published a position paper Normalising research – Promoting research for all doctors with the aim of enabling “a culture in the workplace where doctors are encouraged to be research-aware and research-active”. This makes it clear that action is not just about developing research leaders but changing the culture of the whole workforce, and that research studies should be conducted by multiprofessional groups. Similar support from the GPhC and Pharmaceutical Society of Northern Ireland (PSNI) for research by pharmacy professionals would help normalise research among pharmacy professionals. This is particularly pertinent as pharmacists increasingly become decision-makers in pharmacotherapy. By 2026 all pharmacists who complete their foundation training will register as qualified independent prescribers. This coupled with pharmacy professionals’ close working relationship with medical colleagues in general practice also provides opportunities for conducting collaborative research with the rest of the primary health care team, accessing ‘real world’ patients.

Mentorship and supervision

Several individual respondents indicated the enablers of good mentorship and supervision require an experienced and appropriate supervisory team comprising both clinicians and academic colleagues. The supervisory team must have a good track record for securing research grants and the capability to train people in research practice and coach them in applying for grants. Some felt mentorship should be available from pharmacy colleagues.

Some individual respondents considered an important enabler was being able to speak to pharmacists who already have an established role spanning academic and clinical practice. Similarly, opportunities to work with other clinical disciplines, eg medical consultants, or to connect with HEI or multidisciplinary academic research groups were seen as important enablers.

Two members of the SLWG who were the immediate past NIHR pharmacy advocates (posts now discontinued), anecdotally reported that mentoring greatly increased the quality and success rates of pharmacy applicants to NIHR schemes. The RPS, PRUK and SAPC (Society for Academic Primary Care) provide mentoring schemes, but many pharmacy professionals are unaware of these and there are indications that mentors are in short supply. Communities of practice (based potentially along geographical lines, sector or clinical area) could co-ordinate and promote mentorship and encourage collaboration and networking across the pharmacy profession to support grant and research training applications, and the sharing of good practice. The recently awarded NIHR pharmacy professionals incubator3 will help pump prime this approach, but regional arrangements should also be explored with links to existing infrastructural multidisciplinary resources such as the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) and the proposed NIHR Regional Research Leadership Offices.

Awareness of research training opportunities

Individual respondents identified the need for research training opportunities to be communicated to all pharmacy professionals, not targeted more to pharmacists over pharmacy technicians. Universities could raise awareness of clinical academic practitioner roles among undergraduates.

Respondents felt there was a lack of awareness of research opportunities, and research and development infrastructure. There was also poor senior management engagement from employing organisations. In addition, there was a lack of awareness of the relevance of the research domain in the RPS professional frameworks and curricula.

The NIHR and NHS England should develop a joint communications campaign to raise the awareness of current and previous NIHR/HEE awardees, NIHR and non-NIHR grant and research opportunities, targeted specifically to and working with pharmacy organisations. HEIs could also promote these and provide support and expertise for applications.

Quality of research

Some respondents felt that health services research in some schools of pharmacy was not of equivalent rigour and quality to that in medical schools, and that this was in part due to schools of pharmacy having fewer people with the appropriate expertise and experience to lead and supervise research.

Several individuals reported that the competitiveness and complexity of the application process, particularly for NIHR/HEE research training opportunities, deterred both senior clinician and also early career researchers; these opportunities were perceived as unattainable. Respondents reported they lacked both experience and confidence in applying for research training.

Appendix 1: Data tables

Details of the quantitative responses are reported in the following tables. Frequencies and valid percentages are reported; that is, based on the number of people who answered the question and not the total sample.

Respondent demographics

Table 1: Demographics of the individual survey respondents (n=218)

| Professional group (n=218) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pharmacist | 188 (86%) |

| Pharmacy technician | 30 (14%) |

| Sector (n=169) | |

| NHS trust | 101 (60%) |

| Primary care network | 8 (5%) |

| University or higher education institution | 20 (12%) |

| NHS trust and university or higher education institution | 30 (18%) |

| NHS trust and other | 10 (5%) |

| Geographical location (n=216) | |

| National England | 187 (86%) |

| National Northern Ireland | 3 (1%) |

| National Scotland | 14 (6%) |

| National Wales | 12 (6%) |

| Gender (n=203) | |

| Female | 137 (67%) |

| Male | 66 ( 30%) |

| Ethnicity (n=202) | |

| White (including British, Irish, any other white background | 147 (73%) |

| Black or Black British (Caribbean, African, any other Black background | 8 (4%) |

| Asian or Asian British (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, any other Asian background) | 29 (14%) |

| Mixed (including white and black Caribbean, white & black African, white and Asian, any other mixed background) | 4 (2%) |

| Other ethnic groups (Chinese, any other ethnic group) Prefer not to say | 14 (7%) |

Table 2: Demographics of the organisational survey respondents (n=41)

| Sector (n=41) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| NHS trust | 23 (56%) |

| University or other higher education institution | 10 (24%) |

| Clinical commissioning group | 1 (2%) |

| Community pharmacy | 1 (2%) |

| Primary care network | 2 (4%) |

| National commissioning organisation | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 3 (7%) |

| Geographical location (n=31) | |

| National (UK) | 5 (16%) |

| East of England | 3 (10%) |

| London | 8 (3%) |

| Midlands | 4 (13%) |

| North East | 7 (22%) |

| North West | 2 (6%) |

| South East | 1 (3%) |

| South West | 1 (3%) |

Research capacity and capability in the pharmacy professions

Table 3: Research activity and experiences from individual pharmacy professionals and organisations who support individuals to be research active*

| Individual respondents (n=218) n (%) | Organisational respondents (n=41) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vacation research studentships | 16 (7%) | 10 (24%) |

| Principal or co-principal investigator | 93 (43%) | 27 (66%) |

| Grant holder | 48 (22%) | 13 (32%) |

| Patient public involvement and engagement | 55 (25%) | 11 (27%) |

| Patient recruitment | 69 (32%) | 14 (34%) |

| Data collection | 146 (67%) | 28 (68%) |

| Data analysis | 136 (62%) | 27 (66%) |

| Publication Number of papers per peer reviewed journal: 1–3 4–6 7–9 ≥10 | 132 (61%) 53 (24%) 15 (7%) 9 (4%) 55 (26%) | 27 (66%) (-) (-) (-) (-) |

| *Respondents could tick more than one option, so numbers do not add up to 100%. | ||

Figure 1: Summary of applications to and organisational support for NIHR or other grant applications from survey respondents*

*Respondents could tick more than one option, so numbers do not add up to 100%

Table 4: Research training award applications made by individuals (n=54), and support to individuals for research training awards provided by organisations (n=30)*

| Individual survey respondents (n=54) n (%) | Organisational survey respondents (n=30) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| NIHR Development and Skills Enhancement Award | 3 (6%) | (0) 0% |

| NIHR Advanced Fellowship | 1 (2%) | 4 (13%) |

| NIHR Doctoral Fellowship | 12 (22%) | 5 (10%) |

| NIHR Pre-doctoral Fellowship | 4 (7%) | 7 (23%) |

| HEE/NIHR Senior Clinical Lectureships | 1 (2%) | 2 (7%) |

| HEE/NIHR Clinical Lectureships (replaced by Advanced Clinical and Practitioner Academic Fellowship (ACAF)) | 1 (2%) | 3 (10%) |

| HEE/NIHR Advanced Clinical and Practitioner Academic Fellowship (ACAF) Scheme | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) |

| Clinical Doctoral Research Fellowship (replaced by HEE/NIHR Doctoral Clinical and Practitioner Academic Fellowship (DCAF)) | 8 (15%) | 6 (20%) |

| HEE/NIHR Pre-doctoral Clinical Academic Fellowship (PCAF) | 7 (13%) | 13 (43%) |

| NIHR Masters Studentship (replaced by the PCAF) | 3 (6%) | 3 (10%) |

| HEE/NIHR ICA Internship | 4 (7%) | 6 (20%) |

| NIHR Associate Principal Investigator Scheme | 0% (0) | 2 (7%) |

| Pharmacy Research and NIHR Pre-doctoral Clinical Academic Fellowship | 3 (6%) | 3 (10%) |

| Pharmacy Research UK Research Development Awards | 11 (20%) | 4 (13%) |

| Pharmacy Research UK Research Training Bursaries | 4 (7%) | 3 (10%) |

| Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded Fellowship | 4 (7%) | 2 (7%) |

| Wellcome Career Development Awards | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Wellcome Early Career Awards | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| *An individual or organisation may have made or supported several different applications respectively | ||

Figure 2: Engagement with NIHR infrastructure from individual (n=65) and organisational (n=28) survey respondents*

*Respondents could tick more than one option, so numbers do not add up to 100%.

Enablers and barriers to clinical academic pharmacy careers

Figure 3: Enablers for research training and capacity building reported by individual survey respondent

Figure 4: Enablers for research training and capacity building reported by organisational survey respondents

Figure 5: Barriers for research training and capacity building reported by individual survey respondents*

*Respondents could tick more than one option, so numbers do not add up to 100%

Figure 6: Barriers to research training and capacity building for organisational survey respondents*

*Respondents could tick more than one option, so numbers do not add up to 100%

Appendix 2: Examples of organisational actions taken to increase capability and capacity in the pharmacy professions

Examples of successful research capacity building mentioned by some organisational respondents are illustrated below. The common elements were mentorship for those applying for individual research training awards, support for the conversion of the clinical pharmacy diploma to a Master of Science postgraduate degree through the undertaking of a research project, and the creation of joint posts through strong local leadership between NHS trusts, HEIs and in some cases other local research infrastructure. Such examples should be shared among other pharmacy employers for them to adapt and adopt according to local contexts.

“The pharmacy department has benefited from a reciprocal agreement between the School of Pharmacy and our NHS trust, in which two senior clinical academic members of the Pharmacy Practice Group at the university are given honorary positions within the Pharmacy department at the NHS Trust. Their role at the trust includes the delivery of educational sessions on research topics, mentorship of pharmacists and support with publications, posters and grant writing. In reciprocation, clinical pharmacists undertake roles as clinical tutors for the undergraduate MPharm degree. The hospital trust offers internships, pre-doctoral, PhD and post-doctoral fellowship opportunities. Recently, the local Clinical Academic Centre for non-medical practitioners was launched. It is an initiative between trust and the School of Health Sciences at the university. The work of the Centre has built on the work already undertaken between the two organisations to embed research as a core activity for all non-medics. Any pharmacist or technician who is research active or aspiring to be a clinical academic and is interested in the work of the Centre can sign up to be a member. Members benefits from signposting to research opportunities, teaching opportunities as appropriate, training events, webinars and networking opportunities. Staff undertaking a PhD can join the doctoral college building a community of practice. Those staff with a PhD can become a post-doctoral fellow following nomination” (NHS trust)

“Individuals interested in applying for a research training programme from NICE scholar through to NIHR clinical academic are mentored though the application process by a named member of staff including a mock interview where appropriate. Once accepted, support continues via official routes (academic adviser, supervisor roles) or informally via continued mentoring” (NHS trust)

In house support through mentoring, joining grant applications, grant programmes, writing for publication, joining research teams all of which contribute to gaining pragmatic skills and knowledge rather than theory which are adequately covered through existing university-based postgrad training” (HEI)

“Our organisation research governance process which curates learning materials for anyone aspiring to be involved in research. This gives information about both the internal research governance process which needs to be engaged with to undertake research, but also has information about how to get involved or initiate research, with signposting to other organisations for help and support” (Community pharmacy)

“There is a research network is an established local research cluster consisting of 48 GP practices aligned by a data sharing agreement for research purposes. We consist of a team of multiprofessional clinical leads and are supported to engage with and promote primary care focused research activity in the area” (CCG)

Appendix 3: Members of the short life working group

Representative | Role |

|---|---|

|

David Webb (Co-Chair) Formerly Dr Keith Ridge (Co-Chair) |

Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, England Former Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, England |

|

Professor Christine Bond (Co-Chair) |

Immediate past Chair of the RPS Science and Research Committee (lead of the WG to increase the evidence base for pharmacy) and Emeritus Professor (Academic Primary Care), University of Aberdeen |

|

Professor David Alldred |

Former NIHR Pharmacy advocate. Professor of Medicines Use and Safety, University of Leeds |

|

Professor Claire Anderson |

President of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Professor of Social Pharmacy, University of Nottingham |

|

Professor Darren Ashcroft |

Professor of Pharmacoepidemiology, Manchester Pharmacy School Director, NIHR Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (PSTRC) Deputy Lead, NIHR School for Primary Care Research Manchester |

|

Professor Diane Ashiru-Oredope |

Pharmacist Lead for Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship and HCAI at UKHSA and the Department of Health Expert Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infection (ARHAI) |

|

Professor Emma Baker |

Professor of Clinical Pharmacology and Consultant Physician in Internal Medicine, St George’s Hospital |

|

Professor Debi Bhattacharya |

Professor of Behavioural Medicine, School of Allied Health Professionals, University of Leicester |

|

Professor Louise Brown |

Professor (Teaching), Practice & Policy, University College London (UCL) School of Pharmacy |

| Jane Brown | Pharmacy Dean (North) NHS England Workforce Training and Education Directorate (formerly HEE) |

|

Kevin Cahill |

NHS England Chief Pharmaceutical Officer’s Clinical Fellow 22/23 Office of the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, project lead |

|

Natasha Callender |

Future Practice Advisor, NHS England, project lead and report author |

|

Richard Cattell |

Deputy Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, England |

|

Dr Lisa Cotterill |

Chief Executive Officer, NIHR |

|

Professor Duncan Craig |

Chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council. Dean of the Faculty of Science, University of Bath |

|

Gemma Donovan |

Academic Practitioner, The University of Sunderland. NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow and Former NIHR Academy Forum representative |

|

Andrew Evans |

Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, Wales |

|

Nick Haddington |

Pharmacy Dean (South) NHS England Workforce Training and Education Directorate (formerly HEE) |

|

Dr Kieran Hand |

National Pharmacy and Prescribing Clinical Lead for Antimicrobial Resistance, NHS England |

|

Cathy Harrison |

Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, Northern Ireland |

|

Professor Alison Holmes |

Professor of Infectious Diseases and Director of both the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Healthcare Associated Infections and AMR and the Centre for Antimicrobial Optimisation (CAMO), Imperial College London |

|

Professor Elizabeth Hughes |

Deputy Medical Director, NHS England Workforce Training and Education Directorate (formerly HEE) |

|

Dr Yogini Jani |

Consultant Pharmacist & Clinical Safety Lead, Digital Healthcare, UCLH NHS Foundation Trust. Director, UCLH-UCL Centre for Medicines Optimisation Research & Education (CMORE). Honorary Associate Professor, UCL School of Pharmacy |

|

Professor Ian Maidment |

Former NIHR Pharmacy advocate. Reader in Clinical Pharmacy, Aston University |

|

Professor Gino Luigi Martini |

Managing Director Precision Health Technologies Accelerator (PHTA) and Former Chief Scientist, RPS |

|

Professor Mahendra Patel |

Head of the Centre for Research Equity, University of Oxford |

|

Dr Jignesh Patel |

Reader and Consultant Pharmacist in Anticoagulation, joint Clinical Research Co-ordinator for the Pharmaceutical Sciences Clinical Academic Group at King’s Health Partners |

|

Alison Strath |

Chief Pharmaceutical Officer, Scotland |

|

Professor David Taylor |

Director of Pharmacy and Pathology at the Maudsley Hospital and Professor of Psychopharmacology |

|

Professor Tracey Thornley |

Head of Research Innovations Partnership Team, and Head of Health Innovation and Policy Integration Team Data, Analytics and Surveillance UK Health Security Agency |

|

Mark Voce |

Director for Education and Standards, General Pharmaceutical Council |

Publication reference: PRN00702