What is safeguarding?

Safeguarding is defined by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) as:

‘ …protecting a person’s health, wellbeing, and human rights, and enabling them to live free from harm, abuse and neglect’

Who is at risk?

All patients are potentially at risk of safeguarding issues, but some groups of patients are particularly vulnerable to harm and exploitation.

Vulnerable groups include but are not limited to:

- vulnerable adults and children(where being vulnerable is defined as in need of special care, support, or protection because of age, disability, risk of abuse or neglect)

- those with learning disabilities and cognitive impairment, including those with dementia

- those with disabilities that rely on others to access their record

- those living away from home

- asylum seekers

- children in contact with the youth justice system

- victims of domestic abuse

- those who may be singled out due to their religion, ethnicity, gender identity or sexual orientation

- those who may be exposed to violent extremism

- those with serious mental health conditions

Identifying and managing safeguarding risk

Identifying and managing safeguarding risk is crucial in a digitally enabled primary care system. The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) has developed an adult safeguarding toolkit and a child safeguarding toolkit which provide useful and comprehensive coverage of the roles and responsibilities of all staff in general practice, as well as information about identifying and managing the different types of safeguarding risk.

Once the safeguarding risk is identified, digitally enabled primary care services can help facilitate more effective information sharing, ongoing care, and safe record keeping generally.

Information sharing

Information sharing is essential for the effective safeguarding of adults and children. In many serious-case reviews, poor information sharing has been identified as a key factor resulting in poor care and missed opportunities to act.

The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) published guidance in 2021 in its Data sharing code of practice

A full set of resources around information sharing and safeguarding is listed as the end of this article.

The 7 golden rules

You might find the seven golden rules set out below are a valuable tool to aid decisions around data sharing, especially for safeguarding issues.

- Remember that the GDPR, Data Protection Act 2018 and human rights laws are not barriers to justified information sharing but provide a framework to ensure that personal information about living individuals is shared appropriately.

- Be open and honest with the individual (and/or their family where appropriate) from the outset about why, what, how, and with whom information will, or could be shared, and seek their agreement, unless it is unsafe or inappropriate to do so.

- Seek advice from other practitioners, or your information governance lead, if you are in any doubt about sharing the information concerned, without disclosing the identity of the individual where possible.

- Where possible, share information with consent and, where possible, respect the wishes of those who do not consent to having their information shared. Under the GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018 you may share information without consent if, in your judgement, there is a lawful basis to do so, such as where safety may be at risk. You will need to base your judgement on the facts of the case. When you are sharing or requesting personal information from someone, be clear of the basis upon which you are doing so. Where you do not have consent, be mindful that an individual might not expect information to be shared.

- Consider safety and well-being. Base your information-sharing decisions on considerations of the safety and well-being of the individual and others who may be affected by their actions.

- Necessary, proportionate, relevant, adequate, accurate, timely and secure. Ensure that the information you share is necessary for the purpose for which you are sharing it, is shared only with those individuals who need to have it, is accurate and up to date, is shared in a timely fashion, and is shared securely.

- Keep a record of your decision and the reasons for it – whether it is to share information or not. If you decide to share, then record what you have shared, with whom, and for what purpose.

Digitally enabled primary care can provide opportunities to improve the care of patients with safeguarding risks. This can be through both accurate and detailed GP records, and the sharing of information within and across organisational boundaries. There are, however, risks associated with how information relating to safeguarding issues are recorded, how information is shared, and how sensitive information may become visible to the patient who has online record access.

Sensitive information explained

Understanding what we mean by ‘sensitive information’ is important in identifying the safeguarding issues associated with disclosing information. Examples of sensitive information are:

- that which may put that patient or another individual at risk of serious physical or mental harm

- disclosure of third-party information (not a health or care professional) who has not given consent for the information to be disclosed

- diagnoses, test results and correspondence which haven’t already been discussed with the patient and could potentially cause serious harm

The definition of ‘serious harm’ is subjective and will vary from case to case. It is, therefore, a matter of clinical judgement as to what can be considered serious harm. Broadly, it can be considered as the risk of possible serious physical harm, sexual harm and exploitation, psychological and emotional harm, neglect, discrimination, or financial harm.

Careful consideration of requests for record access therefore needs to be given by patients thought to be at risk of ‘serious harm’.

These issues are also important to consider in providing online access to new GP health record information.

Sensitive data items and codes

These are data items or codes that can be considered potentially harmful to a patient and some commercial tools use this code list to automatically screen records and provide prompts to and suggestions for redaction (which are actioned manually by the person screening. There are codes that are likely to be particularly sensitive. Examples include, but are not limited to:

- serious physical or mental health diagnoses the patient is unaware of

- history of abuse/violence (especially those identified by being subject to Multi-Agency Risk Assessment Conferences or MARAC)

- formal safeguarding codes

- family history of illness, particularly genetic conditions

- substance misuse

- forensic history

- sexual history

- specific medications

- third party references and communications from domestic violence or safeguarding team

Again, the risk of patients having access to this information very much depends on how the information is disclosed, whether the patient is already aware of what is in their record, and if there are any other safeguarding risks such as coercion or abuse.

Safeguarding in digital general practice

There are a number of different aspects of safeguarding in a modern digital general practice.

They are broadly broken into three areas:

- online tools and resources that allow ease of access to safeguarding information and policy

- processing and storing of safeguarding information in primary care IT systems

- safeguarding issues particularly regarding online access to records by patients and any proxies – practices must ensure that any sensitive information (information which is potentially harmful to the patient, or to a third party, such as an informant) is redacted

Online tools and resources

AAt a national level the NHS Safeguarding app provides access up to date legislation and guidance across the safeguarding spectrum. It also provides information on how to report a safeguarding concern and has an up-to-date directory of every local authority in England. The app is available for use on Android and Apple devices from the respective play stores.

The RCGP also has a wealth of information related to both adult and child safeguarding. It provides resources that embed safeguarding into the role of every practice member. Good practice safeguarding in general practice.

Processing and storing safeguarding information on the GP IT system

All primary care staff have a role in ensuring that safeguarding information is stored correctly in medical records. It is, therefore, important that all primary care staff are aware of the following basic principles with regard to how safeguarding information is recorded, processed, and stored on the GP IT systems:

- Accurate coding and documentation of safeguarding information is as important as coding any other significant medical issue. Records should be clear, accurate and readable. Where possible try and record what the patient or informant says verbatim in the notes. Request any consent to share concerns when needed, and document these in the records. There is a full article in this series on keeping high-quality records.

- It is important to document your concerns in the records no matter how minor the concern appears. The notes should reflect the details of any action you have taken, information you have shared and decisions you have made relating to those concerns. This is particularly relevant when documenting safeguarding concerns in children.

- Safeguarding information in a patient’s notes needs to be immediately obvious to all health practitioners who have access to the record for the purposes of direct care (this includes agency staff and locum staff). This can be done using ‘flags’ or similar – your clinical system supplier will be able to provide guidance on how to do this in your particular clinical system.

- Coding and documentation should be of be of the same quality as other medical conditions, allowing GP IT systems to highlight patients who are vulnerable or at risk and enable the offer of appropriate support. (This will vary depending on system in use so please contact your system supplier provider for further details).

- Professional discussions regarding safeguarding concerns need to be transparent, complete, and not inhibited by the concern that a patient may see the record online. These professional discussions or concerns need to be recorded accurately in the medical record appropriately to ensure information is available to all and any clinician when needed. When necessary, records can be redacted before being shared with the patient or family.

- Online access by the patient to their own record should not be a barrier to the recording of the safeguarding information by a clinician for fear that information may be seen. The relevant information should be redacted appropriately.

Organisational alerts/warnings

Alerts are routinely applied to primary care electronic medical records to highlight important issues such as allergies, ownership of weapons, or whether the individual is subject to community treatment orders. In this respect, safeguarding alerts highlight concerns that the individual is at risk of abuse or neglect, or that they pose a risk to others or themselves.

There are no statutory guidelines for applying and managing these alerts and this can pose challenges and risks in ensuring the delivery of safe clinical care.

There are a number of issues related to alerts:

- Triggering an alert | The threshold for applying a safeguarding alert is subjective. As this information is rarely shared beyond the clinical system, it could, however, be argued that this threshold should be low in the absence of national guidelines. If there is consideration of a safeguarding concern that suggests all users are aware, then this would likely meet that threshold.

- Consent | Consent is not required to store safeguarding information or apply an alert on electronic medical records if there is a safeguarding concern or public interest. This is considered both in UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act.

- Responsibility | GP practices may adopt different approaches to managing alerts. It is important to ensure that the responsible person has the expertise and knowledge of the individual while balancing the need to involve many professionals. Ideally, the practice should have a policy for this activity.

- Duration and review | Safeguarding alerts should remain active as long as the risk persists to that patient. Alerts may, however, may be left active longer than intended and should be reviewed as often as practicable.

- Access to alerts | GP practice staff involved in the care of a patient should have access to safeguarding alerts. There is, however, a need to ensure that this information is shared beyond the practice boundary as required (see cross-organizational alerts below).

The way alerts are applied varies from system to system. Please contact your clinical system provider for practical guidance on how to use and apply alerts/warnings in your practice.

Cross-organisational alerts

The Child Protection – Information Sharing Service (CP-IS)

This is a system that helps health and social care professionals share information securely to better protect children and expectant women. It links health IT systems across health and social care and covers 100% of local authorities in England. This includes all GP IT system providers.

When a child is known to social care and is a ‘child looked after’ or on a child protection plan, basic information about that plan is shared securely with the NHS. If that child attends an NHS unscheduled care setting, the responsible GP/ healthcare team is alerted and the social care team is automatically notified. Both parties can see details of the child’s previous visits to unscheduled care settings in England. The same applies when the mother of an unborn child is subject to an unborn child protection plan.

This system is implemented in slightly different ways depending on the GP system provider. Contact your provider for specific information on how to use cross organisational warnings within the system.

NHS England provides detailed information on CP-IS.

Coercion

Careful consideration needs to be given to the safeguarding issues involved when there is any suggestion or suspicion of coercion. Where this is the case there may be a need to limit or withdraw patient-facing online services. There is more detailed guidance on coercion and online access in general practice in another article in this series as well as guidance from the RCGP.

Proxy access

Patients who have capacity can allow a proxy, typically another family member or carer, to have access to their record. The patient needs to be made aware that the those with proxy access may have access to the records and may come to know sensitive details which could harm the relationship with the patient or others, and possibly lead to safeguarding concerns if this access granted led to harm.

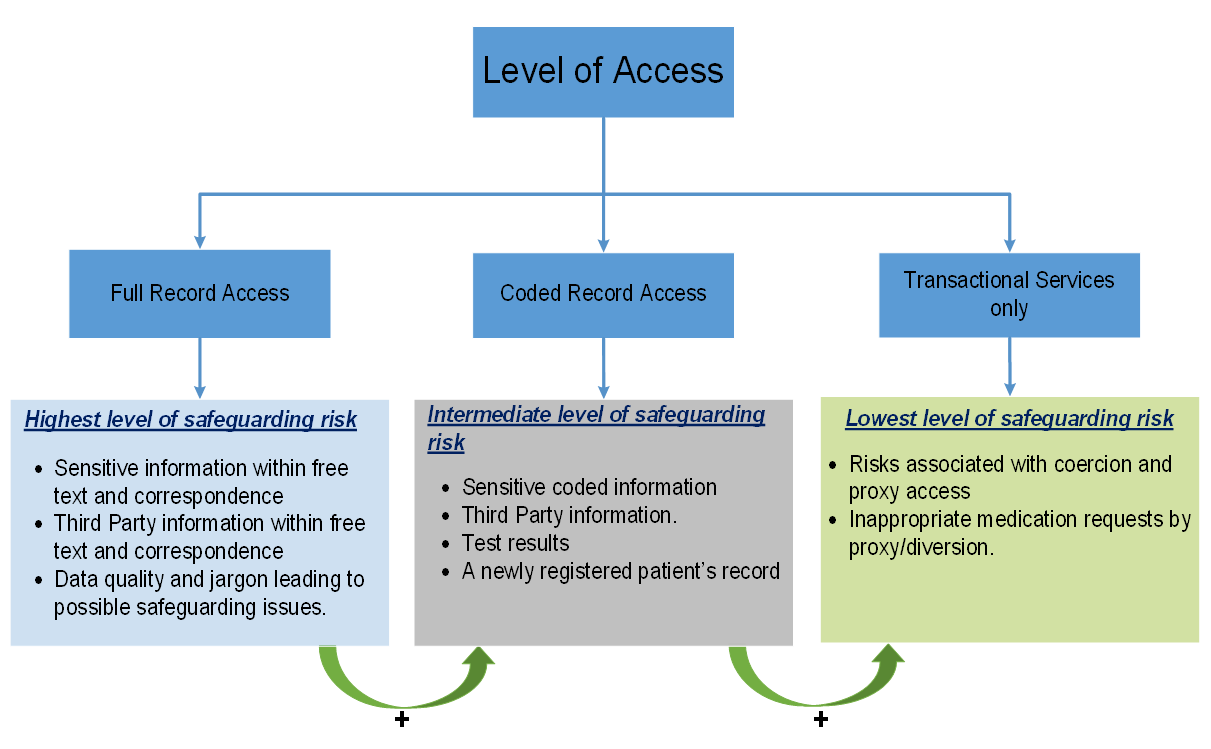

Level of risk by level of access

Although the contractual requirement is now to offer all patients prospective record access on request, for individual patients it may be necessary to limit the level of access to reduce safeguarding risks.

The figure below gives some of the risks associated with each level of access. The highest levels of access are associated with the highest level of risk due to the detail included within the records. It is important to understand that the full record access includes the risks associated with lower levels of access. Risks associated with coercion and proxy access need to be considered at all levels.

Please contact us if you have any issues reading the above diagram: england.dpc.goodpracticeguidelines@nhs.net

Anyone entering information into the patient record needs to consider the impact of each entry in regard to possible safeguarding issues. If there are concerns, it may be possible to redact the information or deny or remove online access, even on a temporary basis.

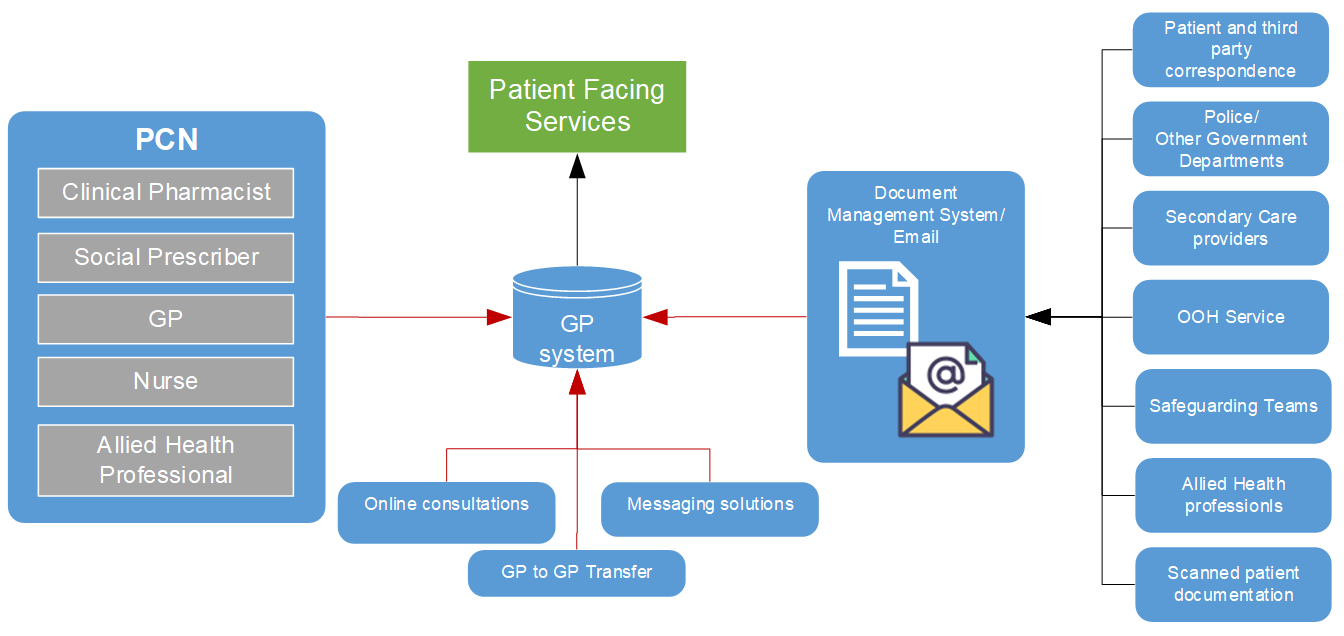

Information flows into the patient online record

The patient’s online GP record reflects the information contained within the practice’s clinical system. Information comes from an increasing number of sources. Once reviewed and approved, the information can be visible in the online record.

The diagram below shows the different sources of patient information that come into the GP system. Whilst most of these flows will not contain sensitive information or present safeguarding concerns, there is that potential. For that reason, it is vital that the practice is aware of their own data flows and how to manage sensitive or safeguarding information as it enters the GP IT system.

The red flows in the diagram are examples of where practices need to minimise the risks of sensitive information being entered into the GP system in a form that is visible to the patient online. An example would be the need to redact safeguarding team reports when they are checked in though the document management system, so they are not visible online.

Please contact us if you have any issues reading the above diagram: england.dpc.goodpracticeguidelines@nhs.net

Similarly, disclosures made via an online consultation or text message which may give rise to a safeguarding concerns would need to be redacted to prevent the information being visible online through patient facing services.

Subject access requests (SARs)

Access by a third party other than an approved proxy also requires consideration of the risk of disclosure. There is detailed guidance on SARs in another article in this series.

Mitigating safeguarding risks in online access

Redaction

Redaction is a key component in reducing the safeguarding risks associated with online access. There is a full article on redaction elsewhere in this series.

All staff entering information into the clinical record need to be aware of what, when how and why to redact information. Different GP IT systems have different ways of redacting content, so ensure all staff can use the functionality in your local system.

There is, however, the need to be aware that redaction alone may not be able to mitigate all risks.

When redaction is not enough

There will be situations where redaction alone is not enough to ensure there are no safeguarding issues.

Example

Ella is a 28-year-old who presented to the practice with depressive symptoms and disclosed to you that her husband has been verbally abusing her and very controlling. She asks the GP not to write anything in her notes as she is worried that her husband will see the record as he has access to her online record. The GP redacts the consultation so there is no record of the discussion and no record of the coding of depression in the online record.

In this case the GP acknowledges the safeguarding risk and redacts the consultation. This does, however, expose several risks:

- if the husband was aware that Ella had been to the GP and is unable to see the entry, he could assume the GP had redacted the information

- even though the consultation may be redacted, Ella may be less confident in presenting due to her own concerns over her husband having online access

This case highlights one of the deficiencies of redaction, i.e. information provided by inference. In this case the husband may infer that the patient has disclosed information about the abuse as there is no consultation in the online record.

This may have been the first time that the practice had any reason to believe there were any safeguarding issues. Having identified a potentially coercive relationship, the immediate solution may be to reduce the level of access, but this leads to placing the patient at risk if the husband infers access has been restricted due to the disclosure of abuse.

Although this sort of situation is likely to be rare, it could become more likely as more patients get full record access (which could be both prospective and retrospective). These situations must be considered on a case-by-case basis, looking at the potential ramifications of each decision and minimising risk.

Communicating with the patient is crucial in order that both parties understand the risks. It may be useful to discuss concerns with the practice or local safeguarding lead, Caldicott Guardian, or medical defence organisation. A plan can then be agreed about how to safely limit online access in the future while the safeguarding issues are being addressed.

Transfer of GP records | GP2GP

Online visibility settings and markers of redacted content are currently not part of a GP2GP transfer. If a patient has some entries restricted for online viewing and leaves the practice, the current guidance is to only allow access to the prospective records from the date they move to the new practice. This avoids the need to clinically assure the patient’s historic record with the associated workload implications. This doesn’t, however, remove all the risks, so it is recommended that an individual assessment of the appropriateness of record access is considered for all new patients.

There is ongoing work by the GP IT providers to transfer visibility and redaction settings during the GP2GP transfer. You should contact your GP IT provider for further details.

Refusing online record access for safeguarding reasons

The UK General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and Data Protection Act 2018 provide a number of exemptions in respect of information falling within the scope of a subject access request. The same exemptions also apply to providing information though access to the online record. Once again these are mainly due to the risk of serious physical or mental harm, safeguarding risks and third-party disclosures. Full details of exemptions are described in the BMA Access to health records guidance.

The circumstances in which records need to be withheld on safeguarding grounds should be rare. Record access should not be withheld on the grounds that the patient may find information upsetting. There must be a reasonable case that it would cause harm. This is clearly subjective and if there are doubts about whether disclosure would cause serious harm, the health professional should discuss with an experienced colleague, area Data Protection Officer, or a medical defence/professional body.

Health professionals need to be reassured, however, that both the UK GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018 offer considerable protection, not only to patient data, but also to the health professional themselves to redact or decline access confidently if there is a safeguarding risk.

Practice safeguarding policy

Your practice will have a safeguarding policy. This should be reviewed to ensure it includes reference to the implications on safeguarding of having digital records. All staff should be made aware of the content.

Ideally this needs to be reviewed, perhaps annually, as clinical systems evolve, and contractual requirements change.

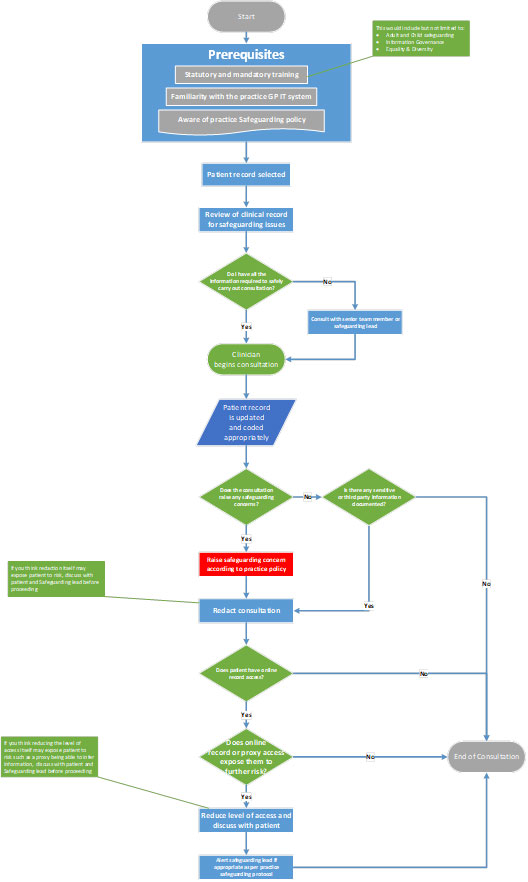

Safeguarding policy process diagram

The diagram below describes the process of safeguarding using electronic health records. These processes need to be included in the practice safeguarding policy.

As shown in the diagram, the consultation itself is only one aspect of safeguarding and there are a number of prerequisites and steps needed before any clinical consultation can begin.

It is important to note that this process needs to occur for all consultations not just those with known or possible safeguarding risks. Practices should ensure that staff (including temporary staff such as locum GPs) are aware of the process as part of the safeguarding policy.

Please contact us if you have any issues reading the above diagram: england.dpc.goodpracticeguidelines@nhs.net

Legal considerations

Safeguarding may lead to contradictory or conflicting obligations, such as confidentiality and disclosure, the need protect the interests of the patient and the need to protect other individuals who may be at risk such as children or vulnerable adults. It can also have far-reaching consequences, as high-profile cases have highlighted. For these reasons it’s important to discuss any difficult situations with the practice or local safeguarding lead, Caldicott Guardian or medical defence organisation.

Training

The GP digital record is a live system and is updated in real time. This means that as an entry is made on the GP clinical system, the data is accessible by the patient through access to their GP record online. Redaction and risk mitigation must be done at the time of entry to avoid possible safeguarding issues.

The training requirements are, therefore, to:

- ensure staff members have the appropriate safeguarding training and that it is up to date

- ensure all staff are aware of the processes involved in redaction especially with regard to safeguarding concerns

- know how to escalate concerns to the safeguarding lead and how to reduce levels of access or remove access completely depending on the risks

- know how the local clinical system implements redaction of sensitive information from the patient’s online GP record from all sources of risk (see earlier section)

- understand the practice’s safeguarding policy to ensure all staff, including GP locums, temporary staff, and visiting allied health professionals are aware of how to immediately redact or limit information from the online patient view when they record information

Training and practice policy is fundamental to ensure effective use of the GP IT system to enable safeguarding.

Related GPG content

- Proxy access

- Coercion

- Redaction

- Subject access requests (SAR)

- High quality patient records

- Clinical coding – SNOMED CT

- Information governance and data protection

- GP2GP – transferred in records – processing

- GP contract

- Online access to new GP health record information

Other helpful resources

- NHS England, safeguarding guidance and policy, including the NHS safeguarding app

- CQC myth buster, safeguarding children (for GPs)

- Medical Defence Union, Online access to records

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH), child protection portal

- General Medical Council, Protecting children and young people – keeping records

- Department of Constitutional Affairs, Mental Capacity Act code of practice (2017)

- Department for Education, Information sharing advice for practitioners providing safeguarding services to children, young people, parents and carers (July 2018)

- General medical Council, Protecting children and young people: The responsibilities of doctors (2018)

- General Medical Council, Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information (2018)

- Social Care Institute for Excellence, Safeguarding adults: Sharing information (2019)

- NHS England, Subject access requests

- NHS England, Practice guidance: Offering patients prospective record access

- NHS Digital, Resources to help staff providing patients with providing record access to patients