Introduction

This report summarises our research into how we can learn from patients’ experiences relating to patient safety. It is written in plain English, to make it as accessible as possible. If you would like more detail, you can also read our full report, but this necessarily uses more complicated language.

We have produced this report as NHS England remains committed to involving people and communities at every stage and telling you how you have influenced our activities and decisions. You can read about this commitment on our Working in partnership with people and communities webpage.

What is LFPSE?

Sometimes things go wrong in care and can make people more unwell. We call these problems ‘patient safety incidents.’

Patient safety is the science of trying to make care safer, working to understand how and why things sometimes go wrong, and how we can improve the way the NHS works to protect patients from harm. It is not about finding people to blame, but instead making sure we design healthcare, hospitals and the work that NHS staff do, to be as safe as possible.

NHS England has a National Patient Safety team who work with NHS staff and organisations of all kinds on this, and lead on finding out what the NHS can do differently to make care safer for patients. They look at information from a lot of different places, and work with many experts of different types to come up with ideas for improvement. They also work with teams that test these ideas in the NHS, to find out if they have helped to make patients safer and suggest the best ideas for everyone to use.

The Learn from Patient Safety Events (LFPSE) service launched in July 2021, to replace old systems. It is a digital service and a single place where all information about patient safety events can go and be used to help healthcare providers and the whole NHS learn, share and improve safety for people who use their services. You can watch a short video about the LFPSE service here: Introducing the Learn from Patient Safety Events service – YouTube.

LFPSE is one part of the NHS Patient Safety Strategy.

What is a Discovery phase?

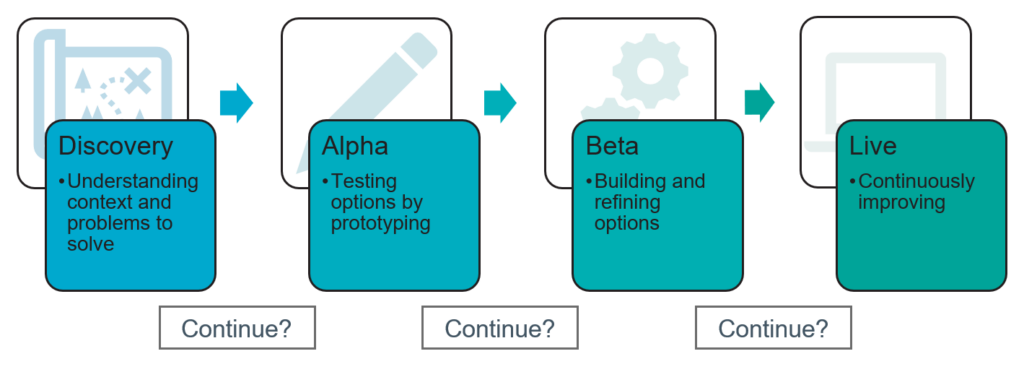

The Discovery phase is the first step in deciding how to solve a problem. It is part of ‘agile development’, which NHS England uses to design new digital services.

Image alternative text:

Discovery: Understanding context and problems to solve

Alpha: Testing options by prototyping

Beta: Building and refining options

Live: Continuously improving

Discovery is the phase where you learn about the problem that needs to be solved before you commit to building a service.

What do you learn about in Discovery?

During a Discovery phase, we try to find out four main things:

- Who are our users and what are they trying to do?

- What is the NHS trying change, or make happen?

- Are there are things that might get in the way that are very difficult to change? For example, because of technology or the law.

- Are there other things we could make better at the same time as we make our main changes? For example, making sure the right people see information.

Why did we do this LFPSE Patient and Family Discovery?

Very little research had been done before to understand the best ways to make sure patients, service users and their families can give their views on safety incidents, for the whole NHS to learn from.

Learning from patients’ experiences and how they feel about the care they have received is known to be a very good way to make healthcare services better.

However, getting the right information from people in the right way, and making sure the right NHS staff see it and can act on it, is difficult to do.

This research starts the process of working out how we can do this better.

What were we trying to find out?

The aim of this Discovery Phase was to think about how patients, service users and their families can share their experiences of patient safety events (things that go wrong in care) to help the NHS learn and do better.

To do this, we needed to learn more about:

- The ways that patients and their families report feedback now.

- The way feedback from patients is used for national learning.

- Things that might stop patients and families’ from telling the NHS about things that have gone wrong.

Our aim was also to look at the best way to use patient and family feedback on safety incidents within the LFPSE service.

We looked at:

- What the NHS needs from this service, both within providers and in national teams.

- How things work now, and what is good and bad about that.

- Who are the most important people involved, and what do they need from this service.

- Research findings from similar exercises by other organisations.

- What our options are, and how well they will give users what they need.

- What could we do next, and what else do we need to find out.

How did we do the research?

First, we did research to find out what systems and processes are already in use to gather patient feedback.

Then, we set up interviews with people in three main groups. We call these interviews ‘user research’, or UR.

Providers – We spoke to this user group to learn about how hospitals and other kinds of healthcare providers find out, store and use patient and family experiences of patient safety events.

National teams – Speaking tothis user group was important to understand what happens to the information from patients and families that is shared with the national team, and how this is used to help the NHS learn and improve.

Patients – This user group was engaged with in order to ascertain an overview of their recording practices and current difficulties surrounding this.

Our objectives

- Understanding what patients and families do when they want to tell the NHS about something that has gone wrong with care, why they want to, and what might get in the way. We want to find out what we can do to make this easier, and for people to do it more often.

- Finding out what all the people involved (patients, families, NHS staff in providers and in national teams) are trying to do and what makes it difficult for them, and then using this information to think of new and better ways to make it work, as well as other things we could make better at the same time.

- Making a ‘map’ of how things work now, including all the different people and organisations involved. This needs to include all the different steps people take, the information they use, any ‘workarounds’ they have to make it easier, and what happens to the information along the way.

- Thinking about the different kinds of information patients and families may give us, and the best ways to turn this into learning that the whole NHS can use to make care safer for patients and service users.

- Making a ‘map’ of how things could work in the future, based on everything our research tells us about how to do it better. This map helps us decide what to do next, in the Alpha phase.

Who took part in this research?

This research was done by members of the LFPSE team, in the National Patient Safety team in NHS England, and their delivery partners, Informed Solutions Ltd.

We ran 34 user research (UR) sessions and in these spoke to:

- 9 people who work in providers/integrated care boards (ICBs). These include people who work in patient safety teams, complaints departments and are patient safety specialists.

- 3 people who work in NHS England’s National Patient Safety team, working on clinical review (NHS staff who read reports about things that have gone wrong, looking for things we can learn from) or as analysts (working with the data to help find learning and support other research).

- 1 person who works in the NHS England Complaints team, handling complaints that come in directly to the national team.

- 21 patients, service users or a member of their family who use the NHS, or care for family members who use the NHS, about their experience of recording patient safety events, as well as people who have had no experience of recording one.

As well as this:

- We used the information from 30 surveys filled in by patients, service users and their families. This survey asked about how they would prefer to record a patient safety event, and what they would expect from any new service that allows this.

- We spoke to 5 patients from a ‘voice of experience’ patient group for disabled patients. We asked them about any extra needs that people with disabilities might have, and talked about accessibility with them.

What were we testing, and what did we find out?

Research assumptions

In this research we wanted to test the following ideas to see if they were correct:

1. Patients want feedback: We believe patients will not want to give information just for incident reporting, but will expect someone to look into it, and get back to them about what they find out.

2. Complaints will feed into NHS England: We believe when a patient makes a complaint to a provider, any learning about patient safety issues from this will eventually feed into LFPSE for national learning.

3. Information will be checked: We believe that providers will want to check any information given by a patient on a safety incident, and make sure it is accurate, before they share it with NHS England for national learning.

4. The NRLS eForm is not easy to find: We believe that because it is difficult to find the NRLS public eForm and, even if they do find it, this form is not written in easily understandable language and won’t give feedback.

5. Friends and Family Test (FFT) data is fed into LFPSE: We believe that information and feedback received through the FFT service is eventually put into the LFPSE.

6. Emotional impact is sometimes ignored: We believe that reports made by staff about things that go wrong in healthcare do not always include enough understanding of or information about how patients have been affected, mentally or emotionally. Staff tend to write down the facts, and do not focus on how patients feel.

7. Not all records will be read by NHS England: We believe that because very large numbers of records are made every year (over 2.5 million) about patient safety events, the national team will not be able to look at every one individually.

Our findings

Through our research, we found the above assumptions to be true, based on the following findings:

1. Our research shows that patients often want to know the outcome of them raising an issue, especially when they have been more seriously harmed. For events with lower levels of harm, many patients feel less strongly about getting feedback.

2. There is no one set way of learning from complaints. Sometimes staff find that complaints contain important information about safety, but complaints teams and patient safety teams do not always speak to each other about what they find. Differences between how teams work together on this is mostly due to numbers of staff and the budgets of individual providers.

3. Providers say they want to be able to check information from patients before it is shared with the national team for learning.

4. Our research confirms that patients and families agree the NRLS eForm is difficult to find. Many do not know it exists.

5. While high level data is fed into the LFPSE, because providers do not include patients’ full comments, there is a chance some safety events or other learning could be missed.

6. Staff are trained to enter just the facts when recording an incident or event. This means other information on how an incident has affected the patient, such as feelings and environment could be missed.

7. Because there is too much data and not enough time or staff, when it comes to learning both national and local teams focus on the incidents that have caused the most severe harm.

8. All of these findings will be tested again during an Alpha phase with larger groups of users, to make sure they are still correct.

Other reports with similar findings

Research has been carried out by other organisations into patient safety recording, specifically within mental health inpatient settings.

You can read the Rapid review into data on mental health inpatient settings: final report and recommendations. The report’s findings are similar to those from our research: the value of patient input, the existence of similar things that stop patients from reporting; concerns among staff that they do not receive useful data that could help them in their roles.

Next steps

Options appraisal

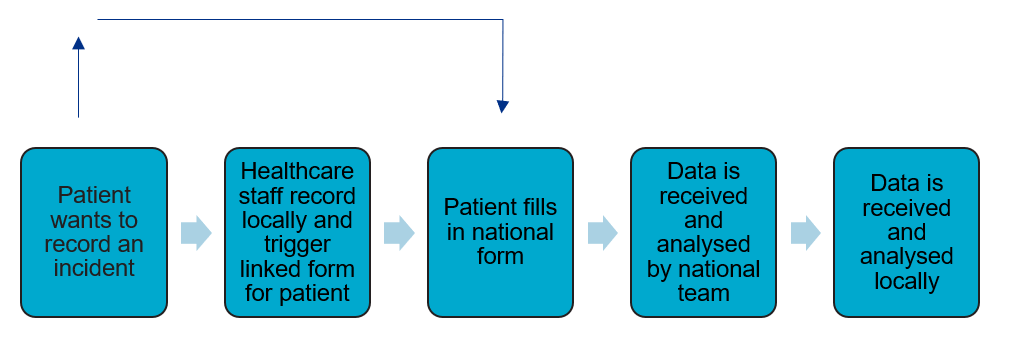

We looked at three main options for a service that would meet user needs.

- A local process where patients fill in a form for their provider.

- A national form (like the NRLS eForm) which patients complete and send to the national team.

- A form that is agreed nationally, which patients can fill in on their own or with their provider, and which is shared with the national team and then back to the provider.

We found that option 3 met the most user needs.

Image alternative text: A diagram outlining the main steps in the hybrid local-national collection option. This process is mostly linear, with the main flow being: Patient wants to record an incident Healthcare staff record locally and trigger linked form for patient Patient fills in national form Data is received and analysed by national team Data is received and analysed locally But with the additional pathway of the patient going directly to the national form, if they do not want to speak to staff locally.

Further work

If the LFPSE team get permission to move on to an Alpha stage (testing options), as well as building test versions, they will need to do more work to understand:

- How can we help patients find out what to do if something goes wrong?

- Can we link up safety recording with other services like complaints?

- What questions should a patient and family recording form ask? What information do patients have to share, and what do they want to tell us?

- Where should the form be available? On a website? On each hospital’s website? On the NHS App? Via a text messaging/SMS service?

- Will this plan work in other kinds of health services, like at general practices and dental practices?

- Will we have any legal or practical problems with sharing information?

- When the NHS and patients talk about ‘investigating’ a problem, are they actually talking about the same thing? Do the suggested options fit well in the new Patient Safety Incident Response Framework?

Publications reference: PRN00858