Summary

The Maternal Care Bundle (MCB) sets best practice standards across 5 areas of clinical care, for implementation by NHS providers and commissioners across England. The aim is to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity and reduce inequalities in these adverse outcomes.

The latest MBRRACE-UK data (2021 to 2023) suggests that maternal mortality has increased by 21% since 2009 to 2011, or 7% excluding deaths relating to COVID-19 infection. In addition to coronavirus, demographic trends such as rising maternal age, obesity and prevalence of pre-existing medical conditions are making maternal care more complex. Stark disparities in outcomes persist. In 2021 to 2023, Black women died at more than twice the rate of white women, and women living in the most deprived areas died at almost twice the rate of those in the least deprived areas. Disparities are also evident in maternal morbidity; among women giving birth in England between 2016 and 2021, 1.6% experienced a severe morbidity with odds up to 89% higher for Black women and 20% higher for women living in the most deprived areas (Geddes-Barton et al 2024). MBRRACE-UK assessors felt that improvements in care could have made a difference for 45% of the women who died between 2021 and 2023. While significant action has been taken in recent years at trust, regional and national level, this data illustrates the urgent need for more consistent, high-quality and equitable care across England.

The MCB has been developed with frontline clinicians, service users and national stakeholder organisations including Royal Colleges, regulatory bodies, professional societies and charities (see Appendix A: Acknowledgments). In this first version, it establishes a baseline of best practice in 5 areas of care associated with higher rates of maternal mortality and morbidity. The 5 elements are:

- Element 1: Venous thromboembolism

- Element 2: Pre-hospital and acute care

- Element 3: Epilepsy in pregnancy

- Element 4: Maternal mental health

- Element 5: Obstetric haemorrhage

These elements were agreed with stakeholders based on the potential for the NHS to reduce variations in care and with them, maternal mortality and morbidity; but also, to reduce inequalities in these adverse outcomes. While the interventions are universal, they all have potential to reduce health inequalities if implemented in an equitable way.

The MCB requires co-ordinated action across NHS services. The factors underlying maternal mortality and morbidity often extend beyond the scope of maternity and neonatal care alone, involving a range of other services including medical specialties, emergency and ambulance services, mental health services and primary care. A whole-system approach is therefore essential.

This first version of the MCB has focused on establishing a minimum basic standard to improve care across the country. This is with a view – as with the Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle – to iterating and building on these standards in future versions.

Background

The latest MBRRACE-UK: Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care 2025 report shows that between 2021 and 2023, 611 women in the UK died during or within a year of pregnancy, 257 of whom during or within 6 weeks of the end of pregnancy, giving a UK maternal mortality rate of 12.82 deaths per 100,000 births.

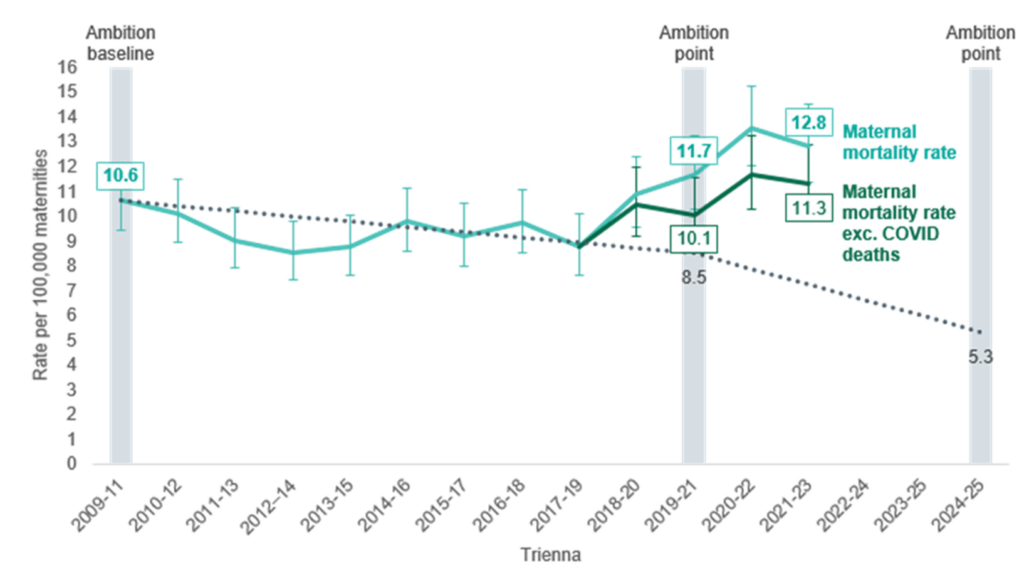

Despite a national maternity safety ambition to halve the rate of maternal death from 2010 to 2025, this rate of mortality represents a 21% increase compared to 2009 to 2011. Figure 1 shows the trend between 2010 and 2023: a modest decrease from the triennia 2009 to 2011 to 2017 to 2019, followed by a steeper increase in mortality rate.

Figure 1: National maternity safety ambition –summary of progress on maternal mortality rates

Assessors found that improvements in care may have made a difference to the outcome for 45% of women who died. This figure was 66% for women who were recent migrants to the UK, whose care was reviewed for the maternal morbidity enquiry, highlighting significant inequalities seen in this particularly vulnerable group.

MBRRACE-UK reports have highlighted persistent inequalities in maternal mortality over a number of years. In 2021 to 2023, Black women died at 2.3 times the rate of white women and Asian women at 1.3 times the rate, and women living in the most deprived areas died at nearly twice the rate of those living in the least deprived areas. In addition, 91% of the women who died experienced multiple interrelated challenges such as co-existing physical or mental health problems, or social complexity, and 14% of women were found to have experienced severe and multiple disadvantage.

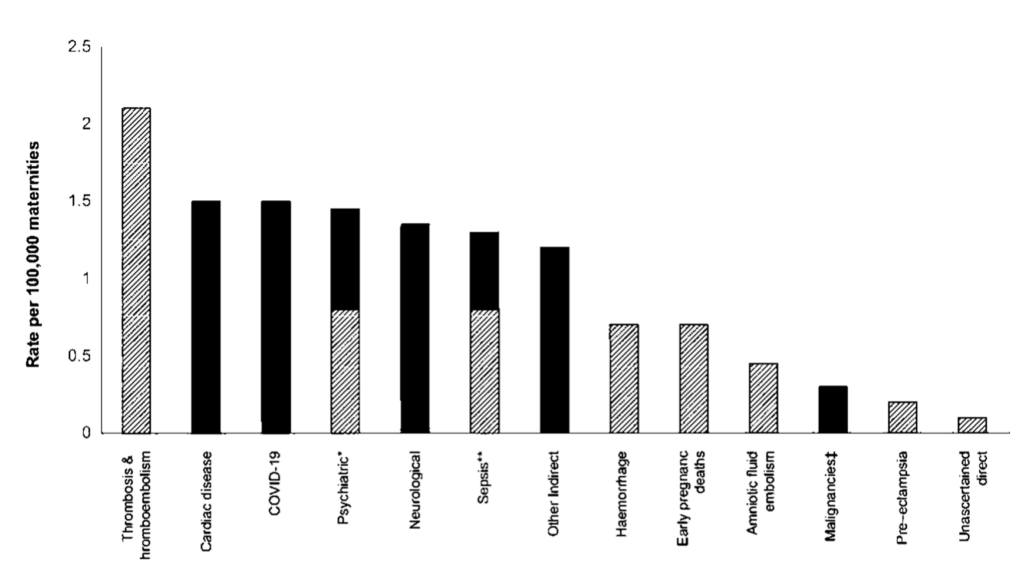

The causes of maternal death are wide ranging and both direct and indirect. As shown in Figure 2, thrombosis and thromboembolism remain the leading direct cause of maternal death, responsible for more than twice the rate of death than any other direct cause. Suicide and sepsis, obstetric haemorrhage and early pregnancy deaths also feature, with no statistically significant change in the rates of direct causes of maternal deaths in the MBRRACE UK 2025 report compared to the previous triennia.

Indirect causes comprised just over half of maternal deaths (54%) in the UK in 2021 to 2023, with cardiac disease and COVID-19 the leading indirect causes and neurological conditions being third commonest.

Figure 2: Maternal mortality rates by cause per 100,000 maternities, UK 2021 to 2023

The maternal population in England is becoming increasingly complex. More women are becoming pregnant who are living with overweight and obesity. More women than ever before have underlying physical and mental health conditions that predate pregnancy. A high proportion of women who die have pre-existing conditions. Nationally the rate of caesarean births is increasing, which is associated with a higher risk of thrombosis and complications in successive births. In addition, for every woman who dies in pregnancy and the 6 weeks after giving birth, it is estimated that more than 100 women will experience a severe adverse maternal outcome, which may have lifelong implications for health.

We know from many MBRRACE-UK reports and the Pregnancy and Baby Charities Network that women do not experience care in the NHS equally. The confidential enquiries frequently highlight where care for women needs to be improved; where pathways were incorrect or could be better implemented; or where national guidelines should be used correctly. These experiences are demonstrable examples of variation in care.

Development of the Maternal Care Bundle

The MCB has been developed to help address local variations and outcomes in care and establish a baseline of best practice in 5 clinical areas associated with the highest rates of mortality and morbidity.

Given the wide-ranging causes of maternal death and severe morbidity, it is clear that a multidisciplinary approach is required. NHS leadership at all levels must drive collaboration between relevant services and specialties, if we are to see the improvements that women and their families need.

The MCB has been developed with input from frontline clinicians across relevant specialties, service users and national stakeholder organisations including Royal Colleges, regulatory bodies, professional societies and voluntary, community and social enterprise representatives. Contributors are acknowledged in Appendix A.

The 5 clinical areas in the bundle were chosen by stakeholders as part of a prioritisation exercise that took account of the potential for improvement in maternal outcomes; the feasibility of NHS services making rapid improvements in these aeras; and the potential for universal interventions to reduce known inequalities in adverse outcomes.

Each element has been developed by an expert working group comprised of frontline clinicians, clinical academics and other subject matter experts and service users. The 5 elements are:

- Venous thromboembolism (VTE) – reducing thrombotic events in early pregnancy by risk assessing all pregnant women at the earliest opportunity before antenatal booking and providing rapid access to thromboprophylaxis for those identified as at high risk.

- Pre-hospital and acute care – ensuring unwell pregnant women receive the right care at the right time through improving access to urgent obstetric and maternal medicine care; and implementing a common approach to the monitoring, identification and management of maternal deterioration across all care settings.

- Epilepsy in pregnancy – improving control of seizures by ensuring timely access to specialist multidisciplinary epilepsy care during and after pregnancy.

- Maternal mental health – improving the identification and response to perinatal mental health concerns through the consistent use of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended screening tools and timely referral to appropriate specialist support.

- Obstetric haemorrhage – improving the management of haemorrhage through standardised approaches to timely identification, escalation and response to obstetric bleeding, along with ongoing multidisciplinary review and learning.

Given the urgency for improvement, this first version of the MCB focuses on establishing a foundational standard to enhance care across England, and one that the NHS will continue to refine and build on in future iterations.

Implementing, measuring and evaluating the Maternal Care Bundle

All NHS trusts providing maternity services and ICBs are responsible for fully implementing the MCB by March 2027.

‘Full implementation’ of the MCB means implementing all interventions for all 5 elements.

Organisational responsibilities

These are:

- NHS trusts providing maternity services are primarily responsible for implementing the MCB locally, including:

- benchmarking current compliance and developing an improvement plan with trajectories for sign off by the trust board

- providing regular reports to the trust board on implementation against this plan and trajectories, so that the board can oversee, support and challenge local delivery. Trust boards should also ensure the involvement of all relevant services in the planning and delivery of interventions. This will include relevant medical and surgical specialties, gynaecology and urgent and emergency care, as appropriate

- ensuring that where local plans do not meet nationally recommended pathways, timescales or performance, or where local delivery subsequently deviates from these plans, this is escalated to the regional NHS England team

- engaging with maternal medicine networks. This means co-producing and complying with the local network’s protocol for the management and referral of medical problems in pregnancy, across all relevant medical specialties and settings

- local reporting of routine care data relating to key process and outcome measures for each element as defined in the national implementation tool (see below)

- ICBs are responsible for ensuring the engagement of wider services within their footprint. This includes the strategic commissioning of relevant services to support delivery of MCB interventions, in line with the Model ICB Blueprint. It also includes facilitating engagement with services on a footprint greater than a single provider trust, for example:

- co-ordination with regional ambulance services and primary care

- joint working between non-specialised and specialised services (such as maternity and adult neurology services)

- escalation of issues between maternal medicine networks and provider organisations

- regional NHS England teams are responsible for providing strategic leadership and oversight of performance, in line with the Model Region Blueprint. Therefore, where local plans do not meet nationally recommended pathways, timescales or performance, or where local delivery subsequently deviates from these plans, this should be escalated to the regional maternity team in the first instance, with input from other regional clinical leadership as required

- maternal medicine networks (MMNs) are responsible for providing regional leadership and support on the management of medical conditions in and around pregnancy, in line with the national service specification for maternal medicine networks. This includes:

- leading the co-production and maintenance of protocols for the management and escalation of medical problems in pregnancy with constituent NHS trusts

- providing advice and training relating to these protocols and advice on relevant local pathways as required

Measuring and overseeing implementation: national implementation tool

To support local implementation, a national implementation tool will be made available to trusts on the FutureNHS platform in quarter 4 2025/26.

For each intervention the tool will include:

- relevant process and outcome measures

- other evidence requirements to demonstrate implementation (for example, the agreement of a local pathway or protocol, or an updated clinical questionnaire)

- charts to help map local performance against these over time

Providers can use the tool to baseline current practice against the MCB interventions, agree a local improvement trajectory with their trust board (and where required, the NHS England regional team) and track progress locally against that trajectory.

While there will be no routine, deadline-based submissions of data to NHS England for the purposes of assurance, the national team will review any data stored on trust implementation tools on an ad-hoc basis to assess national progress in implementation.

Principles and next steps for local measurement

Principles

The development of process and outcome measures will be guided by the following principles:

- measures will be defined as part of developing a full theory of change model for each element and made available alongside the national implementation tool on FutureNHS in quarter 4 2025/26

- minimising data and audit burden: measures will be few in number and based on routine clinical data submitted to national data sets wherever possible

Next steps

While the digital maternity records standard was recently updated, it is clear that many appropriate process and outcome measures for MCB interventions are not routinely reported in Maternity Services Data Set (MSDS) v2.0. NHS England is working to create new metrics and reporting flows as part of MSDS v2.5 and expects to complete this work in 2026.

In the meantime, trusts will be asked to capture the data specified by the implementation tool and as enabled in local maternity information systems or electronic patient records. Reliance on local audit will be kept to a minimum and there is agreement to significantly reduce the need for local audit and extract current data from maternity and neonatal platforms. Only in certain circumstances will local audit be suggested as a form of data measurement.

Evaluation of the Maternal Care Bundle

The Department of Health and Social Care, via the National Institute for Health and Care Research, has commissioned a programme of research to evaluate the MCB, address implementation challenges and inform further evidence-based iterations.

More information will be available in due course on the PRISMM webpage of the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit website.

Wider enablers for improving maternal outcomes

In planning for implementation, providers should consider the following enablers for improving maternal outcomes:

Screening and referral for women with key risk factors in early pregnancy

A number of MBRRACE-UK recommendations highlight the need for action in early pregnancy to prevent adverse outcomes relating to VTE and epilepsy in particular. In response, element 1 includes an intervention and element 3 a recommendation for urgent actions to be taken for women with key risk factors following ‘first NHS care contact with a positive pregnancy test’.

While there may be earlier opportunities in some instances, referral to a maternity service is the first universal opportunity for risk assessment. Maternity services should therefore ensure the following timely actions:

- Implement screening for key risk factors and conditions in all routes of referral into antenatal care. This will include updating standardised self-referral or referral questionnaires and guidelines or, where these are not in place, engaging with relevant referring services and professionals to ensure awareness (for example, in GP-administered referrals).

- Establish procedures for antenatal referrals to be reviewed with necessary timeliness (see elements 1 and 3) and for high-risk women to be flagged and referred on for specialist review.

Alongside these actions, providers should – with support from ICBs as necessary – engage with local GPs, pharmacists, gynaecology, urgent and emergency care and other services as necessary to embed risk assessment in all settings where a first care contact with a positive pregnancy test might occur.

Effective postnatal handover to primary care, health visiting and managing physicians

MBRRACE-UK data shows that in 2021 to 2023 more women died during the late postnatal period (6 to 52 weeks) than during antenatal and early postnatal care. This highlights the need for local maternal mortality and morbidity reduction strategies to include a focus on postnatal care, in particular effective handover to the GPs, health visitors and managing physicians who will be providing a woman’s ongoing care following discharge from maternity services.

The Improving postnatal care: a toolkit for integrated care boards, partners and providers recommends that all maternity services “implement robust handover processes for women with medical conditions identified or exacerbated during pregnancy. ensuring access to ongoing management, screening and risk reduction”. This also applies for relevant mental health concerns.

More broadly, this toolkit sets out actions for ICBs to improve postnatal care across 4 domains: listening to women; addressing inequalities; supporting the workforce; and taking a public health approach.

In line with this approach, the national service specification for maternal medicine networks requires appropriate postnatal follow-up and ongoing management for all women with long-term or pregnancy-related medical conditions and, where appropriate, that formal follow-up appointments should be arranged with the relevant specialist service that will provide ongoing care.

Personalised care and equity

Evidence shows that better outcomes and experiences, as well as reduced health inequalities, are possible when pregnant women can actively shape their care and support.

Personalised care means that:

- pregnant women have choice and control over the way their care is planned and delivered, based on best evidence, ‘what matters’ to them and their individual strengths, needs and preferences

- pregnant women receiving maternity care make informed decisions. They and their maternity professionals discuss evidence-based options together, exploring preferences, benefits, risks and consequences to enable a safe and positive experience

- for any situation where a decision needs to be made, women are supported by their maternity professionals to understand their options and the potential benefits, harms and consequences of each. They have all the information they need to make an informed decision and give consent, in line with the McCulloch ruling

To enable informed decision-making and personalised care, in delivering each of the 5 elements of the MCB consideration should be given to ensuring:

- care is tailored around the informed decision of each service user and is adapted as their circumstances and preferences change

- each service user has information about all the reasonable options available to them and is encouraged to ask questions about the options so that they fully understand the potential benefits, risks and consequences for them

- service users feel listened to. Through discussions with their clinical team, they are given the time they need to share their circumstances and what matters to them

- barriers related to language, culture, disability and accessibility are addressed to provide equitable care for every woman, including:

- information and resources should be available in multiple languages and formats

- adaptations are identified, implemented and clearly documented to support all women during postnatal reviews and future pregnancies

Given the clear and persistent inequalities by ethnicity and deprivation, NHS services must consider equity throughout planning and delivery of the MCB. NHS services should consider the following as part of every element:

- consider access, experience and outcomes in relation to protected characteristics and other factors influencing inequalities, such as deprivation. Pathways and processes should be changed or additional supportive activity carried out to improve equity

- ensure that the needs of different groups are met, with support increasing as health inequalities increase. This requires use of quantitative and qualitative data about the local population and their health needs, along with co-production (see below), to improve care pathways and implementation processes

- respond to each person’s unique health and social situation, so that care is personalised

Relevant equity considerations are highlighted in the clinical rationale and supporting guidance for each element of the MCB (see below). The national implementation tool will also set out approaches for monitoring equity of access through routine care data.

Equity means that all groups attain the health outcomes of the most advantaged group. To achieve equity, action must be universal but with a scale and intensity proportionate to the level of disadvantage; this is known as ‘proportionate universalism’. For more information, see Equity and equality: guidance for local maternity systems.

Co-production with service users

The MCB has been co-produced with service users and should be implemented and monitored in partnership with local women and families. Involving the maternity and neonatal voices partnership (MNVP) lead in the strategic implementation and oversight of the MCB ensures the service user voice is both heard and shapes the improvement of local services. This will be critical to local success.

Trusts have a statutory duty to involve people and communities in the planning, proposals and decisions regarding NHS maternity and neonatal services in England. The framework for this is to have a formal and funded MNVP with an employed lead and links to local voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector organisations. This enables engagement with women and families through the MNVP to ensure improvements to maternity care are co-produced and provide what local families say they need and want.

Element 1: Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

Element description

Reducing thrombotic events in early pregnancy by risk assessing all pregnant women at the earliest opportunity before antenatal booking and providing rapid access to thromboprophylaxis for those identified at high risk.

Interventions

1.1 Women should be offered the national self-assessment questionnaire on VTE risk at first NHS care contact with a positive pregnancy test. Those identified as being at high risk of VTE should be offered low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and receive it within 72 hours*.

The risk factors are:

- previous confirmed diagnosis of VTE

- hyperemesis gravidarum causing dehydration or immobility (that is, a woman cannot drink without vomiting or struggles to stand up and walk due to symptoms)

- body mass index (BMI) greater than 50

1.2 The ICB has arrangements in place for LMWH to be prescribed in early pregnancy (that is, before antenatal booking) within 72 hours, and for a follow-up consultation to take place within 4 weeks in secondary care*.

1.3 Women identified as being at high risk of VTE and not already taking clot preventing medication should be offered a standardised dose of LMWH:

Standardised dosing of LMWH for women not already taking clot preventing medication**

|

Type of LMWH |

Weight <100kg |

Weight >100kg |

|

Enoxaparin (brand names: Inhixa and Clexane) |

40mg |

60mg |

|

Tinzaparin (brand name: Innohep) |

3,500IU |

4,500IU |

|

Dalteparin (brand name: Fragmin) |

5,000U |

7,500U |

* See supporting guidance below on ‘abortion services’ for women considering an abortion.

** Developed with reference to Bistervels et al (2022). Women already taking clot preventing medication (for example, warfarin, apixaban, others) should contact the healthcare team who normally look after this or GP to check it is safe in pregnancy and ensure appropriate dosing of any alternative clot preventing medication.

Clinical rationale

VTE during and after pregnancy is the leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality in the UK, accounting for 16% of maternal deaths in 2021 to 2023 (MBRRACE-UK data). This represents a near doubling of the rate since 2009 to 2011 (1.26 versus 2.1 per 100,000) and coincides with a significant increase in prevalence of risk factors within the maternal population, including maternal age >35, caesarean birth and increasing maternal BMI.

Urgent action is required to prevent further increases in thrombotic events. A woman’s risk of VTE doubles after conception and rises to 8 to 10 times risk at term and postpartum (Liu et al 2018). In 2024, MBRRACE-UK identified that a quarter of deaths from VTE occurred in the first trimester. Recommendations have focused on the need for an early, simplified risk assessment and rapid access to thromboprophylaxis as soon as the pregnancy is confirmed.

MBRRACE-UK (2025) found that in 2021 to 2023, Black women died of VTE at more than twice the rate of white women (6.51 versus 2.33 per 100,000). This highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to risk assessment and receipt of thromboprophylaxis during and after pregnancy.

This element provides a practical, evidence-based approach to ensure that women at high risk of VTE are identified in early pregnancy and can access thromboprophylaxis urgently following confirmation of pregnancy and before the booking appointment. It is intended to complement the approach from antenatal booking set out in the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ (RCOG) Green-top guideline 37a.

The element is not aimed at women who are receiving long-term anticoagulation. This group of women are advised to contact their usual healthcare team or GP as soon as they become pregnant for an urgent medication review.

Supporting guidance

National self-assessment questionnaire on VTE risk in early pregnancy

- Thrombosis UK has developed a brief, targeted questionnaire alongside a working group of national experts and NHS England. This questionnaire is designed to identify those at highest risk of VTE in early pregnancy. NHS services should adopt this questionnaire in implementing intervention 1.1.

First care contact with a positive pregnancy test

- The term is deliberately broad and intended to encompass all NHS settings where a pregnancy might first be disclosed or confirmed. This includes:

- as a universal backstop, at time of referral or self-referral to a maternity service, but also

- at time of consultation with an abortion service

- in an appointment at a GP practice

- on attendance at an emergency department (ED), fertility clinic, early pregnancy assessment unit or gynaecology services, where pregnancy might first be disclosed or confirmed

- Local implementation should take account of these access points at a minimum, acknowledging there may be others.

Prescribing thromboprophylaxis for women who are at high risk

- Women who are high risk for VTE in early pregnancy using the national assessment questionnaire and who intend to continue with their pregnancy should receive a 4-week prescription for LMWH in the first instance, to ensure continuity of medications up to attending a follow-up appointment.

- There is no need for a routine viability ultrasound before prescribing LMWH, unless there is ongoing vaginal bleeding or a suspected ectopic pregnancy. In these cases, women should be referred to secondary care for review and decision around prescribing LMWH, in line with local policies.

- Women considering an abortion should be signposted to abortion services (see ‘Abortion services’, below). If there is any concern about delay in accessing these services, women should be prescribed LMWH. Otherwise, standard practice will be to cover for 1 week post-abortion.

- Women who screen positive for the risk factor on hyperemesis of pregnancy should – alongside being prescribed LMWH – be referred to an early pregnancy unit or ED for further assessment and management. Once these symptoms have resolved, LMWH can be stopped.

- To ensure equity of access to thromboprophylaxis:

- the prescribing professional should issue a digital maternity exemption (FW8) certificate online so that pregnant women can receive their prescription without charge. Prescribing professionals will need to register for access to this service. Women with an email address can expect to receive the exemption immediately on issue

- while prescribers will be able to reassure women that LMWH and injections are generally safe for use in pregnancy, specialist counselling should be available on request for those who remain concerned after an initial discussion

When pregnancy ends by miscarriage

- High-risk women should receive LMWH for 1 week following the end of pregnancy. It is difficult in practice to determine the exact timing of the end of pregnancy and, in these situations, clinicians should exercise clinical judgement and follow local guidance.

Follow up consultation within 4 weeks of prescription for those continuing pregnancy

- Following prescribing of thromboprophylaxis, the prescribing healthcare professional should ensure that the woman is seen within 4 weeks by local maternity services, to re-evaluate VTE risk and, if necessary, continue prescribing.

Referral or self-referral to a maternity service

- Maternity services should implement the national VTE risk assessment questionnaire in all modes of referral into antenatal care. This will include updating standardised self-referral or referral questionnaires and guidelines or, where these are not in place, engaging with relevant referring services and professionals to ensure awareness and adoption of the risk assessment.

- Referral inboxes will need to be monitored so that women screening positive for VTE risk are referred on to a prescriber and an FW8 certificate is generated in a timely manner.

- All NHS trusts with maternity services should work with ICBs to ensure modes of prescribing and dispensing are in place that enable women to receive thromboprophylaxis as easily as possible, on the assumption that they might not otherwise expect to attend secondary care – that is, for antenatal booking – for a number of weeks:

- NHS England is working at a national level to support prescribing within community services for those in early pregnancy. In the meantime, ICBs should support opportunities for prescribing in early pregnancy through primary care

- where this is not possible, ICBs should consider approaches to prescribing from secondary care

Abortion services

- As set out above, VTE risk increases from the beginning of pregnancy and women remain at risk after a pregnancy ends. Abortion care providers should therefore implement the national VTE risk assessment in their medical questionnaires.

- Women who screen positive for VTE risk should be prescribed LMWH to cover for 1 week post-abortion. LMWH could be provided alongside and in the same manner as abortion medication (for example, by post).

- For medical abortions, LMWH should restart after expulsion of the pregnancy for 1 week. If it is difficult in practice to determine the exact timing of the end of pregnancy, clinicians should exercise clinical judgement and follow local guidance.

- For surgical abortions, LWMH should restart 6 hours after the procedure for 1 week.

- On completion of the abortion pathway, no follow-up consultation is required for the purposes of reviewing thromboprophylaxis.

- However, if a woman does not proceed with an abortion and continues the pregnancy, abortion care providers should – as part of facilitating referral to the chosen maternity service – make her VTE risk known along with medications prescribed. Providers should consider extending the prescription as appropriate to reasonably ensure continuity until more can be prescribed as per maternity referral (see above).

Primary care services

- A woman might disclose pregnancy during an appointment at a general practice or – where self-referral to antenatal care is not offered – might request a GP appointment for the purposes of being referred to a maternity service.

- In this case, maternity and GP services should engage to ensure that these risk assessments are routinely conducted as part of referral into antenatal care. This might be through the revision of web-based processes or, where GPs are referring by email, raising awareness of the VTE risk assessment in early pregnancy.

- Contact with a GP provides opportunity for the rapid prescribing of LMWH to a community pharmacy. This provides obvious benefits in terms of timely access and dispensing.

Attendance at emergency departments or gynaecology services including early pregnancy units

- A woman might attend an ED for a range of reasons, at which time pregnancy might be disclosed for the first time or confirmed by a pregnancy test.

- Trusts should incorporate the early pregnancy VTE risk assessment questionnaire in EPRs to facilitate or even prompt risk assessment when pregnancy is first disclosed or confirmed.

- As part of wider collaboration (see element 2), emergency and maternity services should engage, so that these risk assessments are routinely conducted when pregnancy is disclosed or confirmed. This may be through supporting the woman to self-refer into maternity services, through which there should be opportunity to undertake the risk assessment (see ‘Referral or self-referral to a maternity service’ above).

- As with general practice, attendance at the ED or early pregnancy unit (EPU) is an opportunity for rapid prescribing and dispensing of LMWH if a woman is identified as high risk.

Element 2: Pre-hospital and acute care

Element description

Ensuring unwell pregnant women receive the right care at the right time through improving access to urgent obstetric and maternal medicine care; and implementing a common approach to the monitoring, identification and management of maternal deterioration across all care settings.

Interventions

2.1 Implement the national maternity early warning score (MEWS) tool across all settings for women who are or have been pregnant in the past 4 weeks. This means ensuring timely obstetric team and/or obstetric physician review in line with the MEWS escalation timeframes, according to the total score identified and relevant additional concerns.

2.2 Implement a standardised pre-alert communication system between the ambulance service and labour ward and ensure adequate signage for all labour wards so that ambulance services can convey women with an obstetric emergency or red flags promptly and appropriately.

2.3 Establish acute referral pathways from local services to the maternal medicine centre (MMC) for acutely unwell pregnant or recently pregnant women presenting with symptoms or diagnostic uncertainty necessitating maternal medicine expertise. Maternity services and the maternity medicine network (MMN) should review these pathways annually.

Clinical rationale

The timely detection of deterioration in pregnant and recently pregnant women is fundamental to appropriate investigation and intervention. Acutely unwell pregnant women require specialist, multidisciplinary care and appropriate management that accounts for physiological changes during pregnancy.

Unwell women may seek help from a range of NHS services and settings with varying levels of this expertise including emergency departments (EDs) and urgent treatment centres, gynaecology services including early pregnancy units, NHS 111, 999, primary care, maternity triage or community services. A&E data for 2024–25 financial year indicate more than 149,000 attendances related to pregnancy 2024-25 A&E statistics, reinforcing the need for a coordinated and consistent approach to the assessment and management of unwell pregnant women across all urgent and emergency care settings.

Unwell women may seek help from a range of NHS services and settings with varying levels of this expertise including emergency departments (EDs) and urgent treatment centres, gynaecology services including early pregnancy units, NHS 111, 999, primary care, maternity triage or community services. A&E statistics for 2024 to 2025 financial year indicate more than 149,000 attendances related to pregnancy.

Through the years, MBRRACE and other reviews have consistently identified deaths where – across all these settings – presenting women’s symptoms were missed or misattributed to those of normal pregnancy, or where women did not receive the necessary investigations or treatment owing to concerns around possible impact on the pregnancy. A number of recommendations from MBRRACE-UK focus on ensuring appropriate triage and timely conveyance of pregnant women by ambulance services, and ensuring that pregnant women presenting to the ED with medical problems are discussed with the obstetric medicine team.

There is evidence to suggest that urgent and emergency services are disproportionately accessed by those most at risk of health inequalities, including those who do not understand how to navigate the health and care system in England. In 2024, MBRRACE-UK reported “It was evident from the care of [maternal deaths] reviewed… that many women who had recently arrived in the UK did not understand the NHS or how to access maternity services. Many women booked late in pregnancy, and several presented for the first time in pregnancy to the emergency department”. When women do access urgent and emergency care there is significant, unwarranted variation in whether they can be referred and to where. Improvements in the co-ordination of care across these services is therefore likely to have a significant impact on at-risk groups.

The NHS is in the process of implementing the MEWS tool across England. MEWS will follow the woman wherever she is cared for and will be used to identify deterioration from conception to 4 weeks after birth. The tool is already live in a third of maternity units across England and is planned to be implemented in the remainder by March 2027; that includes in all relevant digital systems based on national digital specifications. UK ambulance services are working to the MEWS physiological parameters as part of the national pre-hospital maternity decision tool, which is designed to help pre-hospital clinicians in the community to identify women who need time-critical assessment in an acute hospital setting.

In addition, maternal medicine networks were established across England in 2022, with responsibility for improving care for acute and chronic health conditions in pregnancy through the establishment of shared protocols across their footprints. Work is required by every NHS trust to ensure that all maternity services and acute care settings are engaging appropriately with MMNs and these protocols.

Supporting guidance

Implement the national MEWS across all settings for women who are or have been pregnant in the past 4 weeks

- Relevant settings include secondary care acute settings, pre-hospital services and community maternity settings (including home births). Primary care settings are not in scope.

- Work to implement MEWS should be led through established trust-level deterioration working groups and associated governance. As a first step, membership of these groups will need to include all relevant perinatal services.

- Hosted by NHS health innovation networks, patient safety collaboratives (PSCs) provide improvement and implementation support for perinatal services in specified clinical areas. From April 2026, this will include support for trust-wide implementation of MEWS on the following themes:

- leadership and staff readiness

- digital readiness

- governance and guideline alignment

- measurement

- Further information on PSCs including local contacts and outputs and resources on MEWS such as digital implementation can be found on the Maternity and Neonatal Safety Improvement Hub on the FutureNHS collaboration platform (login required).

- While the physiological parameters for escalation should be standardised across settings, escalation should be localised so that the relevant clinical team and ward staff are alerted for a particular setting. For example, in a medical ward, escalation might most appropriately be to a consultant physician, paired with active involvement of the maternity team with the overall care planned for that woman.

- For many organisations, local implementation of MEWS will depend on integration into relevant electronic record systems. A national digital specification has been developed for the digital integration of MEWS and is being prepared for publication. The latest draft digital specification is available on the Maternity and Neonatal Safety Improvement Hub. From an early stage, trusts should – with support from their PSC – open discussions with their digital suppliers to agree timelines for local integration in line with the digital specification and locally agreed contracts. In parallel, NHS England is also engaging with key digital providers and scoping further options to encourage proactive adoption.

- The national pre-hospital maternity decision tool in the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) guidelines has the MEWS parameters embedded within it. Ambulance services should ensure ambulance clinicians use it consistently for the timely and appropriate assessment of pregnant, suspected pregnant and recently pregnant patients.

Standardised pre-alert communication system

- A pre-alert is when the ambulance service notifies a destination of an incoming patient who requires immediate assessment or interventions. Depending on the presentation, the destination may be an ED, a labour ward, a heart attack centre or a stroke specialised centre.

- If an ambulance crew is taking a pregnant or recently pregnant woman to a labour ward, it is paramount that they have a dedicated telephone line that should:

- be used by the ambulance service to inform the maternity service unit of an incoming patient who is birthing, has birthed, has red flags according to the tool or has an ongoing obstetric emergency

- be answered by a midwife or doctor

- be in an area that is accessible 24/7 (not in an office)

- exist in one place within the maternity unit (not have multiple red telephones for each ward within maternity); the designated place should be the labour ward

- only be issued to the ambulance service (that is, not given out to other services as an advice line)

- The person answering the call should receive the information from the ambulance service in a one-way conversation and then inform the appropriate members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) of the incoming woman.

- The ambulance service should inform the person answering of the key information on the incoming woman using their pre-alert structured tool (for example, SBAR, ATMIST, CASMETE) and an estimated time of arrival. They may also request an escort to meet them at the pre-agreed entrance; this is because ambulance clinicians work regionally and may be unfamiliar with the unit.

- On arrival to the unit, the maternity service should receive a full clinical handover from the ambulance service using a structured tool (for example, SBAR, ATMIST, CASMETE) and take over care of the woman.

Adequate signage and access for labour wards

- Clear and appropriate signage to the labour ward is essential to help ambulance crews locate the labour ward in a timely way. Labour wards are variably located within hospitals, which means that they can be difficult for ambulance crews to locate when conveying women during an emergency. Crews work regionally and may be conveying a woman to a labour ward that they have never been to before.

- Signage to the labour ward should:

- be visible and clear from the ambulance service vehicle as it arrives at the hospital site

- be in red and state “Maternity ambulances” so that it is clear to all crews regardless of whether they work locally or not

- take the crews to the appropriate parking area for the ambulance vehicle

- include clear and appropriate signage from the parking area to the labour ward by foot

- include a route that is suitable for stretchers

- consider access issues, for example door access, swipe cards

- Work to ensure adequate signage and access should involve estates management, maternity unit staff and the ambulance service. It is recommended that the signage is tested by clinicians who do not regularly access the labour ward.

Referral pathways from local services to the maternal medicine centre (MMC)

- These pathways should ensure equitable and effective referral of pregnant or recently pregnant women to the MMC when maternal medicine expertise is required or there is diagnostic uncertainty, in line with the MMN’s agreed protocol for the management and escalation of medical problems in pregnancy. Maternity providers should:

- co-develop with the MMC and adopt clear criteria for referral, ensuring alignment with local population needs and clinical expertise

- implement standardised referral protocols using agreed templates and timelines, with providers responsible for maintaining consistency and ensuring staff adherence

- establish integrated communication channels, with providers accountable for ensuring their teams have access to secure messaging, virtual MDTs and helplines

- ensure managing clinicians regularly attend MMC MDT meetings to discuss relevant cases within their care

- lead local training and awareness initiatives, embedding MMN referral education into local continued professional development (CPD) programmes

- support feedback loops, enabling MMNs to share insights and outcomes that inform provider practice and service improvement

- champion service user voice, incorporating feedback into local governance and quality assurance processes

- To ensure equity of access across the MMN, providers should:

- contribute to geographical coverage mapping, identifying local gaps and supporting telemedicine solutions

- embed demographic sensitivity into referral practices, ensuring culturally competent care and access to translation and advocacy services

- monitor access and outcomes, working with MMNs to collect and analyse data that highlights disparities and informs targeted interventions

- enable flexible referral options, ensuring that all frontline staff – from midwives to emergency clinicians – understand and can activate MMN referrals

- Annual review and audit of impact should be co-owned by all providers within an MMN:

- provider trusts should participate in review meetings, using MMN audit findings to reflect on referral quality, timeliness and outcomes

- audit framework metrics should include:

- number and type of referrals

- timeliness of response

- patient outcomes

- equity indicators

- providers should update local protocols, training and digital systems based on audit insights to drive continuous improvement

For further information, refer to the national service specification for maternal medicine networks.

National policy development and testing

NHS England’s Maternity and Neonatal and Urgent and Emergency Care Programmes will scope additional actions to support co-ordination between maternity, early pregnancy, emergency, maternal medicine and other relevant services, so that pregnant or recently pregnant women requiring urgent and emergency receive the right care in the most appropriate place.

Element 3: Epilepsy in pregnancy

Element description

Improving control of seizures by ensuring timely access to specialist multidisciplinary epilepsy care during and after pregnancy.

Interventions

3.1 Every pregnant woman with epilepsy has access to a local epilepsy in pregnancy team who will ordinarily lead the early pregnancy, intrapartum and postnatal care plans in line with the local maternal medicine network’s (MMN) management and escalation protocol. The local team will consist of, at a minimum:

- epilepsy nurse specialist or neurologist

- maternal medicine obstetrician (see national service specification for maternal medicine networks)

- obstetric physician (subject to local availability)

3.2 Women requiring more complex epilepsy care should be referred by the local epilepsy in pregnancy team to a maternal medicine network (MMN) multidisciplinary team (MDT) who can oversee and – where necessary – lead the provision of care.

Clinical rationale

Women with epilepsy are at significantly higher risk of complications during pregnancy and the postnatal period. MBRRACE-UK (2025) reports that in 2021 to 2023 neurological conditions were the third leading indirect cause of maternal mortality after cardiac disease and COVID-19; and the fifth leading cause of deaths overall.

MBRRACE-UK’s report for 2019 to 2021 identified missed opportunities for specialist input and a need for better communication between services. The early postnatal period is also one of the highest risk times for seizure exacerbation due to rapid hormonal shifts, fatigue, and medication changes. MBRRACE-UK has highlighted that gaps in early postnatal epilepsy care need to be bridged to prevent maternal deaths.

Early access to co-ordinated care between maternity and neurology services can prevent adverse outcomes through timely review, medication optimisation and continuity of support across the care pathway. MDT working is known to improve the care of pregnant women with epilepsy. MBRRACE-UK has recommended that clear standards of care be developed for joint maternity and neurology services, to support the risk assessment and minimisation of women with epilepsy before, during and after pregnancy.

In line with this and NICE guidance (NG217), the recently updated national service specification for adult neurology services (August 2025) requires the establishment of pathways to ensure timely access to “specialist multi-disciplinary clinics for pre-pregnancy counselling” for women with epilepsy and other significant neurological conditions; “rapid optimisation of medication in early pregnancy”; and “postnatal medications review”. It also requires “close working with Maternal Medicine Centres to ensure co-ordinated specialist care for complex conditions in and around pregnancy”.

This element sets out the local expertise and regional working arrangements that should be in place across NHS services to ensure all pregnant women with epilepsy can receive this timely specialist care.

Supporting guidance

Local epilepsy in pregnancy team

- The objective for the local epilepsy in pregnancy team is to provide timely specialist, multidisciplinary care closer to women than is possible for the maternal medicine centre’s (MMC) MDT. The local team should be able to provide face-to-face care in the same consultation. This consultation should take place where the woman has booked for maternity care. This can include members of staff who work in that hospital permanently, or who can visit for sessions regularly enough to provide ongoing care during pregnancy. Where services are particularly remote, it is acceptable for some members of the MDT to join consultations remotely.

- This team is expected to facilitate informed women-centred decision-making, equity of access and streamlined access to information, and formulate multidisciplinary care plans and ensure continuity of care.

- While intervention 3.1 sets out the minimum staffing requirement for the team, services are encouraged to expand the team to include additional healthcare professionals where appropriate to meet local needs, such as specialist midwives. It is recognised that the appropriate clinician to lead the local epilepsy team will vary and should be agreed locally.

- Expectations around ‘expertise in pregnancy’:

- the neurologist and/or epilepsy nurse specialist should have clinical experience in the management of epilepsy in pregnancy in addition to ongoing evidence of continued professional development (CPD). They will provide expertise around diagnosis and seizure classification, medication management, therapeutic drug monitoring (where applicable) and seizure risk assessment.

- the maternal medicine obstetrician must either have training in maternal fetal medicine or have gained expertise in the management of women with epilepsy through specialist interest training modules (SITMs) or alternative clinical experience or training. They are expected to be able to lead overall co-ordination of the pregnancy pathway including integrating neurology advice into antenatal care, ensuring that the schedule facilitates maternal and fetal monitoring. They will input into the delivery plan and intrapartum care, liaising with other healthcare professionals such as anaesthetists where required.

- where locally available, an obstetric physician should also co-ordinate the overall care of women with epilepsy during pregnancy (see role description in the national service specification for maternal medicine networks).

- Education of the team should be led by the MMN. Annual multidisciplinary regional teaching sessions should be provided by the MMN and target the following staff groups: primary and secondary care clinicians, midwives, obstetric anaesthetists, specialist nurses, pharmacists and allied health professionals.

Co-ordination with maternal medicine networks

- Care should be provided in line with the regional MMN’s management and escalation protocol. Where a local epilepsy in pregnancy team is in place, conditions within Category A of this protocol can be managed locally. However, for conditions within Category B or C of the protocol – or for all cases of epilepsy where a local epilepsy pregnancy team is not in place – the case should be referred to the MMC for MDT review. This may result in guidance or a management plan for ongoing local care, or transfer of care to the MMC. See the national service specification for maternal medicine networks for further details.

- Pathways of referral to the MMN should define criteria for referral, state named contacts in both local and network teams, outline the method of referral (secure email, electronic referral, telephone for urgent cases), specify expected response times for urgent and routine cases. They should be incorporated into local maternity guidelines and staff induction.

- Key features of good engagement with a maternal medicine centre

- early and appropriate referral: based on agreed criteria (see national service specification for maternal medicine networks)

- clear and consistent communication: clear documentation of plans in the woman’s notes (handheld or digital) with the women fully informed and engaged in the decision-making. This should also be communicated to other relevant healthcare professionals

- continuity of care: named consultant or co-ordinator (that is, specialist maternal medicine midwife) for maternal medicine input

- ensure safety-netting and support, with a clear pathway for urgent advice

Expert consensus recommendations

Timings for local case review, triage and medication reviews

- While local epilepsy pregnancy teams should provide care in line with agreed MMN protocols (see above), the element 3 working group recommends by expert consensus that services work to put in place local pathways so that every woman with epilepsy receives:

- a case review and triage by a member of the local epilepsy in pregnancy team within 2 weeks of first NHS care contact with a positive pregnancy test, and that highest risk (see criteria below) women are then seen in person for medications review within a further 2 weeks (so 4 weeks from first care contact).

- a follow-up appointment (in person or virtual) with a member of the local epilepsy in pregnancy team within 14 days of the end of pregnancy, to review medications and discuss post-partum risks and contraceptive options. This plan should be communicated to primary care and the woman’s neurology service.

- The term ‘first NHS care contact with a positive pregnancy test’ is deliberately broad. As a universal backstop, it includes time of referral or self-referral to maternity services for antenatal care, but also the following care contacts where pregnancy might first be disclosed or confirmed:

- in an appointment at a GP practice

- on attendance at an emergency department (ED), fertility clinic, early pregnancy assessment unit, gynaecology services or other urgent and emergency care setting

- routine gynaecology or neurology clinics

- From that first contact, a referral should be made urgently to the local epilepsy in pregnancy team. Where a healthcare professional outside maternity is unable to refer directly to this team, they should refer the woman (or support her to self-refer) for maternity care as soon as possible, making clear her epilepsy and prescribed medications.

- The case review and triage may be undertaken by any member of the epilepsy in pregnancy team (see intervention 3.1).

- Key local enablers for successful implementation are:

- clear, standardised referral pathways from all NHS entry points (maternity, primary care, ED, early pregnancy services, neurology, community services) to the local epilepsy in pregnancy team

- IT integration – where possible use electronic flags and alerts in maternity and primary care systems and work towards automated referral triggers from coded pregnancy diagnoses in neurology or GP records

- equity of access – provide accessible information for women, ensure interpreters are used where needed and address barriers for those with cognitive impairment, low health literacy or complex social needs

Timeliness of medications reviews and defining ‘high risk’ for urgent review

- All women identified through case review as requiring a medications review should receive this as soon as possible.

- However, as above, it is recommended that women with high risk factors should be offered a medication review to take place within 2 weeks of the case review and therefore within 4 weeks of the first NHS care contact with a positive pregnancy test

- It is recommended that women are considered ‘high risk’ if they meet one or more of the following criteria:

- uncontrolled, frequent, or nocturnal seizures (including clusters)

- use of multiple anti-seizure medications (ASMs)

- use of high-risk ASMs, particularly sodium valproate and topiramate

- history of status epilepticus

- co-existing physical or mental health conditions

- intellectual disability

- unplanned pregnancy or no pre-pregnancy counselling

- severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (hyperemesis gravidarum)

- alcohol or drug misuse

- poor adherence to treatment or antenatal care (for example, missed medication, late booking, missed appointments)

- safeguarding or social support concerns

- epilepsy diagnosis in question

- nocturnal seizures or sleeping alone

- current treated epilepsy with a duration of over 15 years or early onset below 16 years old

Postnatal follow-up consultations and handover

- Planning for the postnatal follow-up:

- the appointment should be scheduled during the antenatal period, to ensure timeliness

- the date of and appointment type (in person or virtual) for postnatal epilepsy review should be communicated to the woman

- offer virtual appointments where clinically appropriate but provide in-person access for women who face digital exclusion or require physical examination

- consider offering enhanced community midwifery postnatal follow up for up to 28 days

- Clinical content of the review:

- seizure history since birth or other reason for end of pregnancy

- medication adjustment, including safe de-escalation of doses post-birth or other reason for end of pregnancy where indicated

- postpartum seizure triggers and safety advice (for example, infant handling during seizures, sleep strategies)

- contraceptive counselling, with consideration of anti-seizure medication interactions

- breastfeeding safety information for prescribed medications

- mental health screening and referral if needed

- A written postnatal care plan should be shared with:

- the woman

- primary care

- neurology service (where applicable)

- any other relevant community health teams

- all information should also be uploaded to the Electronic Patient Health Record (EPHR)

- Education and engagement:

- women should receive accessible information covering postnatal seizure risks, medication safety, contraception and self-care

Equity

- Service user information and resources should be available in multiple languages and formats.

- Ensure that adaptations are identified, implemented and clearly documented to support all women during postnatal reviews and future pregnancies.

- This includes addressing barriers related to language, culture, disability and accessibility to provide equitable care for every woman.

National policy development and testing

NHS England will consider the findings of EPISAFE – a national epilepsy in pregnancy safety improvement programme – for any future iterations of the MCB, alongside all other relevant published research.

Key guidance documents

- Specialised neurology services (adults) – service specification

- NICE guideline 217: Epilepsies in children, young people and adults

- Green-top guideline 68: Epilepsy in pregnancy

- National service specification for maternal medicine networks

Element 4: Maternal mental health

Element description

Improving the identification and response to perinatal mental health concerns through the consistent use of NICE recommended screening tools and timely referral to appropriate specialist support.

Interventions

4.1 As part of routine emotional wellbeing screening, women should be invited to self-administer the Whooley questions ahead of the:

- booking, 25–28 week and 31–34 week antenatal appointments; and

- 10–14 day postnatal appointment

4.2 When a woman responds positively to either of the Whooley questions or there is concern, she should be invited to complete a further assessment using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Where appropriate, this could be by self-administration.

4.3 If a woman screens positive using EPDS (scores 13 or above in total or 2 or above on self-harm) or there is clinical concern, allow sufficient time in the same appointment to offer the woman a compassionate conversation to explore needs, discuss care options, agree next steps and receive referral to appropriate services if indicated.

Clinical rationale

Psychiatric causes, including suicide and substance use, were the fourth leading cause of maternal death in 2021 to 2023, with suicide remaining the leading cause of death between 6 weeks and 1 year after the end of pregnancy (MBRRACE-UK, 2025). Emotional wellbeing and social circumstances can change rapidly during the perinatal period. Conditions such as anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and tokophobia may emerge or worsen at different stages of pregnancy and after birth (Fairbrother et al 2025; Wikman et al 2020).

National guidance (NICE CG110; NICE CG192) recommends routine assessment of emotional wellbeing at every antenatal and postnatal contact. Regular screening supports early identification of emerging or escalating concerns and enables timely, proportionate responses. This aligns with NHS England’s Staying safe from suicide guidance (2025), which emphasises the importance of continuous review and adaptation of care in response to changing circumstances.

The Whooley questions, as recommended by NICE (CG110; CG192), provide a validated, evidence-based method for identifying depression in the perinatal period. Their brevity and sensitivity make them suitable for consistent use in maternity care to identify emotional wellbeing needs early.

However, while the Whooley questions provide an initial indication of possible mental health difficulties, they offer limited insight into symptom severity or type and do not ask about suicidality. This is important because 50–77% of women who die by suicide have no diagnosed mental health problem (Sher 2024; Oquendo et al 2024; MBRRACE-UK 2025 respectively). NICE (CG192) recommends EPDS as a follow-up assessment for women who screen positive using the Whooley questions.

Evidence demonstrates that self-administered mental health screening tools are both accurate and acceptable in perinatal populations. EPDS has superior validity and when self-administered is as acceptable to women as clinician-administered measures (El-Den et al 2015). Both paper-based and digital formats are feasible in routine care (Kaminsky et al 2008; Johnson et al 2021). Self-completion may enhance comfort, autonomy and disclosure, particularly among women who find direct questioning difficult (Kingston et al 2015). When positive responses are followed by a compassionate discussion with a clinician, referral and access to mental health support increase significantly (Smith et al 2022; Waqas et al 2022).

Concerns that self-administration reduces engagement or accuracy are not supported by evidence. Lower disclosure rates are more often associated with how questions are asked – for example, in impersonal or rushed conversations during busy appointments – rather than the method of administration (Crampton et al 2016). Women with high levels of stigma or need for privacy prefer self-completion (Buist et al 2006; Buist et al 2015). Self-administration followed by a compassionate, reflective review therefore represents a more consistent approach to routine emotional wellbeing assessment.

Supporting guidance

Whooley questions

1. During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

2. During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

- NICE recommends that these questions are asked at every antenatal appointment. Intervention 4.1 builds on this by recommending self-administration of the Whooley questions ahead of the appointments specified above.

- Self-administration would ideally be offered through a digital platform or alternatively on paper before the appointment.

- Registered healthcare professionals should review the self-administered responses during the appointment with the woman present, using empathy, active listening and open dialogue to encourage the woman to feel comfortable to share any concerns and to build trust.

- If the woman answers “yes” to either question, or if the clinician has ongoing concern despite negative responses, she should be asked to complete the EPDS.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

- EPDS will provide a clearer indication of symptom severity, including suicidal ideation, and support informed referral decision-making.

- Maternity services should determine the most suitable method for delivering the follow-up EPDS assessment. For example, where digital capability allows, it may be efficient to deploy the Whooley questions electronically and automatically deploy the EPDS if a woman’s answer to either question is “yes”. In any case, maternity services should establish capability to conduct and record EPDS digitally as part of routine antenatal and postnatal care contacts, beginning with a conversation with the maternity information system provider to identify a plan and associated timescales. In the meantime or for paper-based organisations or where a woman screens positively for Whooley during the appointment, it may be deemed best to provide the EPDS face to face, rather than ask the woman to complete EPDS later by herself.

- A registered healthcare professional should review the results of EPDS with the woman and the score must be recorded in the maternity record.

- A positive screen for EPDS includes any of the following and should trigger the registered healthcare professional to have a compassionate conversation with the woman:

- scoring above 13 across all questions

- scoring above 2 on question 10 (relates to self-harm)

- where there are continued clinical concerns

Compassionate conversation and onward referral

- This conversation should take place in a safe and confidential space. The registered healthcare professional should ask questions sensitively and respectfully, avoiding intrusive or distressing approaches that could re-traumatise the woman.

- Confidentiality must be maintained, with clear explanation of safeguarding responsibilities and information-sharing thresholds. Where significant concern or risk is identified, escalation must follow established local pathways, with prompt referral to appropriate services.

- Documentation in the electronic patient record should include Whooley responses, EPDS results (when completed), whether a follow-up conversation occurred, key concerns discussed, actions taken, agreed interventions, referrals offered and whether any referrals were accepted or declined and referral completed.

- When there is clinical indication for referral to specialist mental health services and the woman agrees to the referral, the clinician should use the EPDS score alongside other clinically relevant information (for example, presentation, history, risk assessment) to support the referral by facilitating appropriate triage and timely access to mental health care.

- Ensure the woman is provided with relevant contact details to ‘reach out’ if any concerns, distress or emerging issues arise. As part of routine practice, follow up at the next appointment or earlier if needed to confirm that any required referral has been made and appropriate follow-up is in place.

National policy development and testing

Areas of interest for any future iterations of the MCB are:

- the feasibility and effectiveness of using the EPDS as a first-line, self-administered tool before maternity appointments to improve efficiency, identify symptom severity and support referral decisions. The aim is to improve early identification, minimise pressure on appointments and facilitate better support for women with emerging or established mental health needs

- methodologies for the identification of social risk factors as a means of targeting care and support.

Element 5: Obstetric haemorrhage

Element description

Improving the management of haemorrhage through standardised approaches to timely identification, escalation and response to obstetric bleeding, along with ongoing multidisciplinary review and learning.

Interventions

5.1 Measure cumulative blood loss for all births in community and secondary care settings. This includes ensuring access to key resources including:

- scales – available at all births with swab weight chart to record and assess blood loss accurately

- under-buttock blood collection drapes for assisted vaginal births

- access to an obstetric haemorrhage emergency kit – that is, a trolley or grab bag for all births and postnatal settings

- documentation tool for individual patient records to be updated in real time

5.2 Standardised definition and reporting of postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) and points of escalation by cumulative measured blood loss:

- by 500mL loss* and ongoing bleeding:

- for community births, escalation and help sought, with plans made for immediate transfer to secondary care.

- in secondary care, midwife in charge and the first-line obstetric and anaesthetic staff should be alerted

- by 1,000mL loss,* senior midwife, obstetrician (ST3 equivalent or above) and anaesthetist should all be present and managing as an obstetric emergency

- by 1,500mL loss,* consultant obstetricians should be informed, with attendance required if bleeding ongoing, unstable or deteriorating

- standardising reporting of PPH at 1,500mL*

* Clinical judgement should be used to escalate earlier if required, taking into consideration the woman’s individual risk factors that may lead to an earlier deterioration and the skill mix of the clinical team attending.

5.3 Multidisciplinary team (MDT) case review should be undertaken for all women with significant bleeds (>2L) and all cases of cryoprecipitate and fibrinogen concentrate use within a month.

Clinical rationale

Obstetric haemorrhage was the eighth leading cause of maternal mortality in the UK in 2021 to 2023 (MBRRACE-UK, 2025).

It is one of the most common complications during birth and so is known to be a significant contributor to severe morbidity, associated with hundreds of hysterectomies and intensive care unit admissions each year (Jardine, NMPA Project Team 2019), along with long-term psychological consequences including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for women who have experienced significant bleeds and their partners. The MBRRACE-UK Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care 2023 key messages and the Care Quality Commission 2024 also highlight a need to improve detection of significant blood loss, prevent delays in escalation or leadership and improve situational awareness to reduce the occurrence of fatal haemorrhage.

Significant inequalities persist in adverse outcomes relating to haemorrhage. MBRRACE-UK data shows that in 2021 to 2023 Black women died of haemorrhage and amniotic fluid embolisms at more than 3 times the rate of white women (3.24 versus 1.04 per 100,000) and Asian women at nearly double the rate (1.81). This underlines the need in every maternity service for ongoing review and learning from adverse outcomes that is sensitive to race, deprivation and the mode and setting of birth.

Longitudinal analysis suggests there has been no significant reduction in the mortality rate from haemorrhage in the past 15 years. A number of national recommendations from MBRRACE-UK and other organisations focus on the need for the timely identification and escalation of the care of women with significant bleeds.

The interventions for this element set a baseline of practice to support the timely identification and escalation of significant bleeding and so ensure the involvement of senior clinicians to bring about a prompt and effective response. They have been developed to align with the approaches of the ongoing OBS UK study, while much needed evidence is generated on further areas of practice.

Supporting guidance

Cumulative, measured blood loss

- Visual estimation of blood loss is inaccurate. Cumulative objective measurement can improve early recognition of haemorrhage and supports timely escalation.

- Blood loss should be measured in all settings, including community births, using a validated method that combines volumetric (fluid from suction and/or drapes once amniotic fluid has been accounted for) and gravimetric (weighing of swabs and pads) measurements. The following should be considered:

- Gravimetric measurement requires scales for all births:

- gravimetric measurements will be derived from weighing blood on swabs and pads by weighing and subtracting the known dry weight to give a blood loss in millilitres

- ensure calibrated digital scales are available and functional in all secondary care birth settings, with weighing integrated into standard practice and documentation

- in the case of vaginal births, the under-buttock pad should be replaced immediately after birth to enable amniotic fluid to be discounted from future loss measurements

- in community settings, cumulative measures should be achieved utilising hand-held weighing scales if available, placing contaminated swabs and pads in a clear plastic bag to protect the scales. Scales should be thoroughly cleaned and decontaminated prior to weighing the baby if using the same scales

- Co-located postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) emergency kits:

- ensure all secondary care birth settings and postnatal areas have a clearly labelled, restocked and regularly audited PPH kit (trolley or grab bag)

- for community births, midwives should have access to a standardised obstetric haemorrhage emergency kit in line with local policy

- Volumetric measurements:

- volumetric measurements will be derived from under-buttock drapes, drains and suction containers placed after birth to ensure amniotic fluid has been excluded

- under-buttock blood collection drapes are required for assisted vaginal births

- stock in all assisted vaginal birth kits and resus or PPH trolleys

- Pool births:

- where blood loss is suspected in a pool birth, midwives should activate the pool evacuation procedures and start cumulative measurement as soon as possible

- Real-time documentation tool

- provide a swab weight chart to standardise conversion (for example, 1g ≈ 1mL of blood). This could helpfully be part of the documentation tool used for real-time measurement alongside swab counting procedures