Foreword – Professor Chris Whitty and Professor Steve Powis

The last systematic review of medical training was over 15 years ago. Over that time the epidemiology of disease, the demography of the country, technology, medical practice, the structure of the medical profession, the career aspirations of those entering medicine and the public perception of the profession have changed very significantly.

Medical training has also changed, but change has often been piecemeal and incremental. While a perfect training system for everybody will never be possible, the level of concern about current medical training is now clearly substantial.

This diagnostic report is designed to identify major concerns and areas where the system is working well. The overall question is whether further incremental change is the right response or has the time come for a more fundamental rethink of medical training?

In producing this report on current training in medicine in England, we have started from a number of principles. The most important principle is that the main point of training is to improve future health outcomes for patients and the wider population. If it does not achieve that, it is failing. We therefore consider some of the division between service and training time to be artificial. Both aim to improve the health of our patients, although formal training is principally for the future patients a doctor will see over their career, while service work is for current patients under their care now. Working out how best to structure training, and then delivering it, is the responsibility of the medical profession, and we should not be expecting others to do it for us. This report is principally a reflection back to our professional colleagues at all stages of their career of what they and their peers have said about training, and how it should change.

There is a longstanding principle that learning in medicine occurs throughout the entire path of a doctor’s working life: this remains true. Training begins on the first day someone enters medical school and finishes on the last day of a doctor’s career. Whatever discipline we belong to, all the way through our medical career we are both being trained ourselves and training others. We have a responsibility to our patients to continue learning in a scientific profession that evolves rapidly, and to contribute to the learning of our colleagues whether through providing formal or informal teaching or ensuring that other doctors can have the training they need.

The balance between time spent being trainer and being trained varies over a career, but all doctors should be doing both and the distinction between ‘trainee’ and ‘trainer’ is often unhelpful. Nevertheless, the early years following first qualification are when the highest proportion of time is and should be spent learning. This report concentrates on that specific period but has implications for doctors later in their career.

There are important differences between the training needs of different parts of the medical profession, although sometimes these are exaggerated. The training needs of, for example, craft specialties, psychiatry, general practice, physicians, public health and academic medicine have much in common, but also some clear differences and any effective training system must take these into account. We also need to reflect that the structure of the medical profession is different from the last time training was looked at in the round. Over 15 years ago there was an assumption that the great majority of the medical profession would either be in a formal training role or be an established consultant or GP. A much higher proportion are now in roles that are neither, including specialist, associate specialist and specialty (SAS) doctors and locally employed doctors (LEDs), but are also essential to current and future patient care. These doctors’ training needs, contribution to the training of others and future practice need to be part of any model of training.

We are conscious that this report is landing at a time of increased dissatisfaction among resident doctors and others in the profession. Many of the concerns of colleagues are not about training specifically but other important issues. We divide those broadly into 3 groups. The first is around pay and associated financial issues. We consider pay and finance to be an issue for negotiation between the government and medical unions and it has not been specifically considered in this diagnostic review. The second is around conditions of service including how rotas are constructed in a fair and timely manner and other important practical issues such as hot meal availability for those working night shifts. These are fundamentally about the proper and respectful employment of hard-working professionals, although we recognise that poor working conditions can negatively impact on training. The third is, directly or indirectly, about our current models of training, and it is on these that this report concentrates.

We also looked internationally, including at other high-income countries with similar demographic profiles that train excellent doctors but in a different way. Although this is a report for medical training in England (which is our mandate), we have discussed medical training with many colleagues in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and we are conscious that any changes in England will have implications for the other 3 nations of the UK. If changes are made we recommend they are made on a 4 nations basis.

Much of medical practice is about identifying trade-offs and trying to balance them, and the same is clearly true for medical training. Many of the concerns we heard about were clearly and equally reasonable, but create some tension for prioritisation. For example, many colleagues identified that training was too rigid and they wanted greater flexibility so that they could pursue skills and experience relevant to their future career. Others, for good practical reasons – to secure accommodation or childcare, or co-ordinate careers with their partner – wanted greater predictability. Both are reasonable but point in different directions. As a profession we need to be realistic about the trade-offs any new training models will entail.

We also need to be aware that changes in something as complex as medical training introduced in good faith to solve one set of problems can make things worse for other areas of training. Anyone who doubts this will want to read the accounts of the introduction of Modernising Medical Careers, especially the Medical Training Application Service, which was well intentioned but caused chaos. Even well designed and executed changes often have teething problems that cause short-term difficulties for trainees and trainers alike, so there should not be a default assumption that widespread change in training will in itself make things better.

With that caution acknowledged, we do consider the major issues raised by colleagues, and in particular medical professionals early in their career, are unlikely to be resolved by incremental change alone. Although this is a diagnostic report, we have gone further than simply laying out the evidence and in Chapter 3 make a number of high-level recommendations. We highlight 4 in particular.

The first is that for many early career doctors the training period has become highly inflexible, and any changes need to increase rather than decrease the ability of doctors to vary their training to reflect their career needs. The second is that the strict division between those who have training posts (‘numbers’) and those who do not does not reflect current reality; many excellent doctors are getting their training outside these formal routes. The third is that the current bottlenecks in training do not benefit anyone; while some competition has always been a necessary part of medical training and career progression, especially in the most popular disciplines, the current ratios are making sensible career planning and assessment very difficult. The fourth is that wherever possible we should try to recreate a team structure that doctors at all stages of training feel part of, without reverting to the old ‘firms’ that had some significant problems.

When we asked for input into this diagnostic review, we received an overwhelming and exceptionally helpful response from medical students through to doctors in late career, from trainers and from patient representatives. This came from multiple stakeholder discussion groups, structured surveys, people writing in with examples of good and bad practice and their opinions in response to calls for evidence and directly to us. We made clear at the start of this process that this was to be an initial diagnostic report, rather than an attempt to provide a detailed blueprint for future training.

We are confident this report reflects what we have heard and encourage the medical profession, other professional groups and patients to continue discussing the issues we have described and highlight any we may have omitted. But we now need more than just a diagnosis and this diagnostic report should be followed by specific, detailed discussion on possible proposals for change that the profession, patient representatives and other interested parties can be consulted on. Further recommendations are laid out in Chapter 3.

Chapter 1. Background to the Medical Training Review

1.1 Introduction

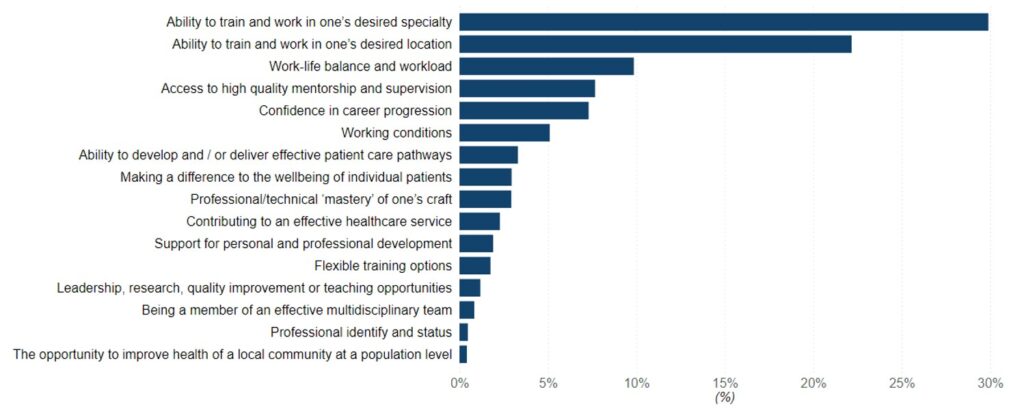

1. Postgraduate medical training in the UK has followed the same model of delivery for the last 2 decades, but in that time the health needs of the population and the way medicine is practised have changed dramatically.

2. Increases in life expectancy have led to a higher proportion of people in the later decades of life, usually with multiple health conditions. Older people are increasingly living in rural and coastal areas while much of our healthcare resource, including the NHS workforce, remains concentrated in urban settings.

3. The nature of medical practice has changed, including an increasing emphasis on outpatient and day case care, the introduction of telemedicine and changing structures of general practice.

4. A greater proportion of the medical profession is in posts that are not consultant or GP posts, or designated as training posts.

5. Part-time and shared working practices have become more common.

6. At the same time, more doctors are graduating from UK medical schools and increasing numbers of international medical graduates have come to work in the NHS.

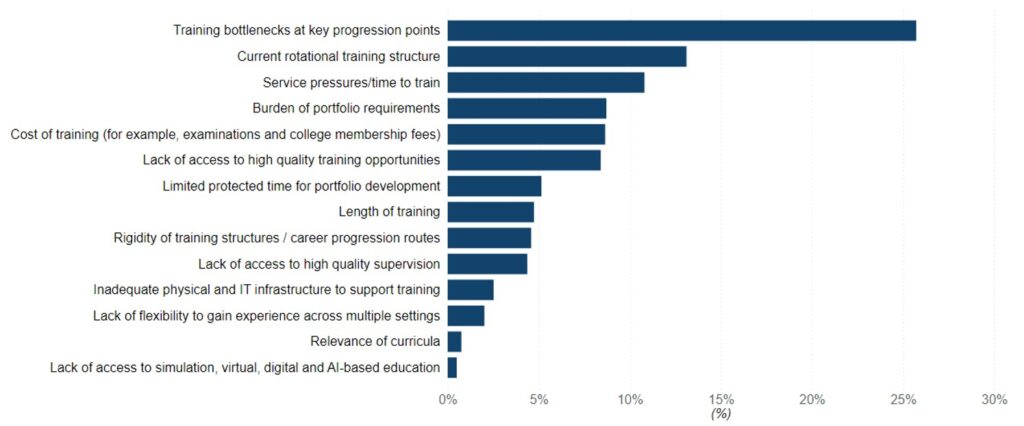

7. As of 2025/26, 8,126 undergraduates will start medical school every year, but they may not complete training until 2040, and the 8,090 first year foundation doctors currently in post will not complete training to become part of the substantive workforce until the next decade. Some doctors starting in 2025 will still be training their successors in 2070.

8. There has been a significant increase in the proportion of new joiners to the medical register attaining their primary medical qualification (PMQ) overseas (from 47% in 2017 to 68% in 2023) and they now represent 66% of those in locally employed doctor (LED) roles and 81% of those in specialist, associate specialist and specialty (SAS) roles (GMC Workforce report 2024).

9. There is marked variation in the proportion of international medical graduates between training programmes, from 4% in public health to 52% in GP training Overall, the proportion of doctors in training programmes who attained their medical qualification outside the UK has risen from 18% in 2019 to 27% in 2023 (GMC Workforce report 2024).

10. Although postgraduate medical training places have grown in number, this expansion has not kept pace with growth in the medical workforce, resulting in ever increasing competition for formal training posts. This in turn has led to increasing disquiet from resident doctors (formerly known as junior doctors) and significant pressure on our educator faculty.

11. At the same time aspirations of doctors at the start of their careers have changed.

12. It is timely, therefore, to review how we train and develop the medical workforce.

13. Phase 1 of the Medical Training Review, which is the subject of this report, has been a comprehensive listening exercise. We have gathered the opinions of all stakeholders and the evidence we need to understand the issues across our formal training programmes and also those faced by LEDs and SAS grades, so that we can develop options for future reform in the way doctors are trained and developed.

14. While we recognise that training is intrinsically linked across the 4 nations of the UK, this review focuses on England.

1.2 Evolution of postgraduate medical education in the UK

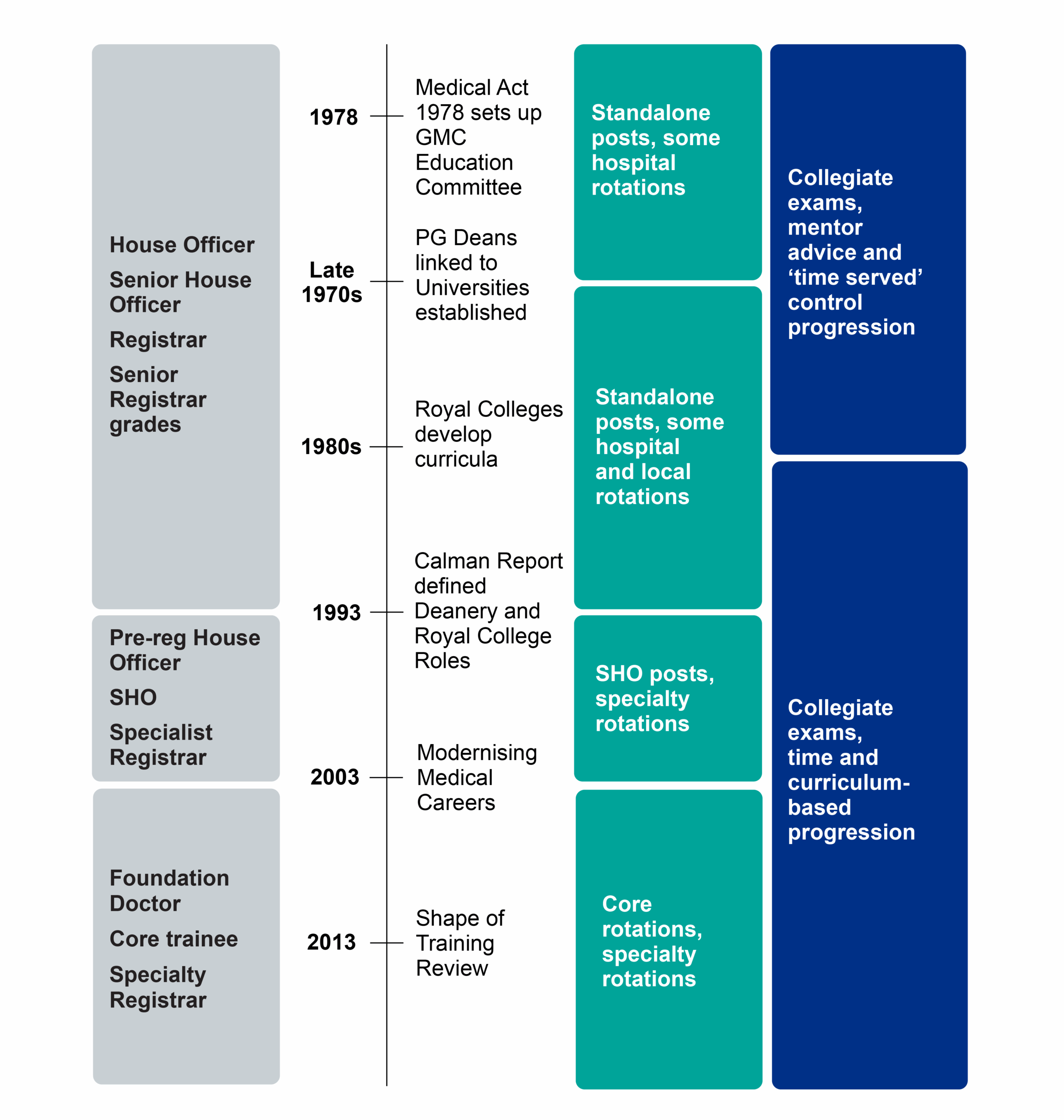

15. As with the rest of the NHS, postgraduate medical education training has been subject to numerous reviews and reorganisations (Figure 1).

Figure 1: History of postgraduate medical training, 1970s to 2013

16. The basis for continuing postgraduate medical education was set out in the 1944 Report of the Inter-Departmental Committee on Medical Schools (the Goodenough Report) and formalised in the 1950 Medical Act. Further changes arose from the ‘Christchurch Conference’ of 1961 and a complex structure evolved for the management of postgraduate medical education with responsibilities shared between the NHS, the medical Royal Colleges and the General Medical Council (GMC).

17. Hospital doctors: training for the future (1995). Significant reforms took place during the 1990s, instigated by the then Chief Medical Officer, Sir Kenneth Calman. These led to the introduction in 1996 of specialist registrar posts, with explicit curricula and regular assessments of progress, limited to a maximum of 7 years whole-time equivalent (WTE). The reforms also introduced the Certificate of Completion of Specialist Training, awarded by the GMC, and the requirement that all doctors had to be on the GMC Specialist Register before being able to take up a substantive consultant post.

18. These reforms marked the start of structured training programmes and educational support within postgraduate medical training.

19. General practice training has developed from a voluntary Vocational Training Scheme in the 1970s to a 3-year programme leading to entry to the GP Register or Performers List, contingent on passing the Membership of the Royal College of General Practitioners examinations. Over time this programme has shifted to a greater focus on training in primary care settings, rather than secondary care.

20. Modernising medical careers. In August 2002, the Chief Medical Officer for England, Sir Liam Donaldson, published Unfinished business, describing a number of problems experienced by some doctors in the junior training grades, particularly at senior house officer (SHO) level. Unfinished business set out 5 principles for the reform of the SHO grade: training should be programme based, time limited, broad based to begin with, flexible and tailored to individual needs.

21. To achieve this, the consultation proposed the introduction of a 2-year “foundation programme” after medical school, followed by broad-based “basic specialist training programmes” in 8 different specialty areas, including general practice. Unfinished business stressed that the new programmes should allow trainees the flexibility to leave and then re-enter training and should address the needs of non-UK graduates.

22. Unfinished business received widespread support during the consultation process and, in February 2003, the 4 UK health departments published Modernising medical careers (MMC) in response, endorsing both the principles and many of the practical proposals set out in the report, including the creation of a 2-year foundation programme.

23. However, the implementation of MMC ran into significant problems, primarily due to the failure of the electronic Medical Training Application Service (MTAS) but also because of concerns over perceived inflexibility within this system, particularly the application of run-through training across all specialties. At the time this was designed to reduce blocks to training progression and provide geographical stability. The result was that MMC changes and in particular MTAS, while starting from reasonable and widely supported principles, were seen as having caused more harm than good (Appendix H).

24. Aspiring to excellence. As a consequence of these issues, Sir John Tooke was commissioned to undertake a review of postgraduate medical training. His report, Aspiring to excellence, was published in 2007. This report made several recommendations including the ‘uncoupling’ of certain specialties into ‘core’ training for 2 years and ‘higher specialty’ training for 5 years.

25. The report also recommended the creation of a national body to take responsibility for medical education. Medical Education England (MEE) was established in 2008 and superseded by Health Education England (HEE) in 2012, a key difference being that HEE then held the budget for training while MEE had not.

26. Shape of training review. The Shape of training review, published in 2013, sought to address how medical training should adapt to meet changing population health needs, particularly those of an ageing population with chronic and multimorbid conditions. It focused on the need for the development of better generalist skills and possible “credentialling”.

27. The formation of HEE in 2013 as the statutory education body for resident doctors brought with it iterative reform, with the 2020 Future Doctor and Enhancing Generalist Skills programmes and reform to increase access to less than full-time (LTFT) working and opportunities for out of training programmes (OOP). The creation of a national body reduced the variation in training across the country as postgraduate deans worked together to standardise processes.

28. While the current overarching delivery model for training has been in place for over 20 years, significant incremental reform has been put in place by postgraduate deans and the statutory education bodies across the 4 nations in recent years to improve the experience of resident doctors:

- British Medical Association (BMA) industrial action in 2017 led HEE to establish the Enhancing doctors working lives (EDWL) programme, now within NHS England. This has resulted in increased access to flexible, LTFT and portfolio training opportunities across all specialties:

- introduction of self-directed learning time in foundation and some specialty programmes

- wider options for time OOP

- development of the Supported Return to Training (SuppoRRT) and CareForMe programmes for those who have been away from training and clinical practice for an extended time

- the Future Doctor consultation resulted in the development of the Enhancing Generalist Skills programme

- NHS England set up the Improving doctors working lives programme to address the transactional human resources (HR) factors affecting resident doctors

- the GMC, with the statutory education bodies, moved towards capability rather than time-based training

1.3 Overview of current postgraduate medical training

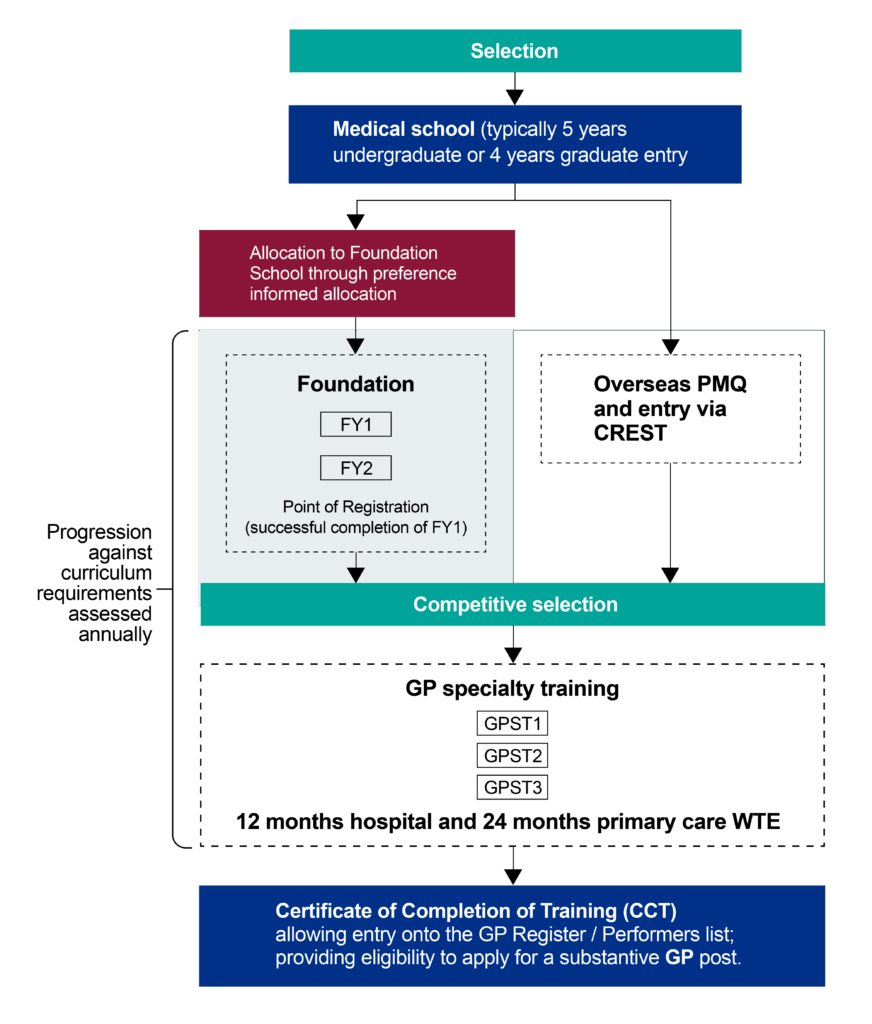

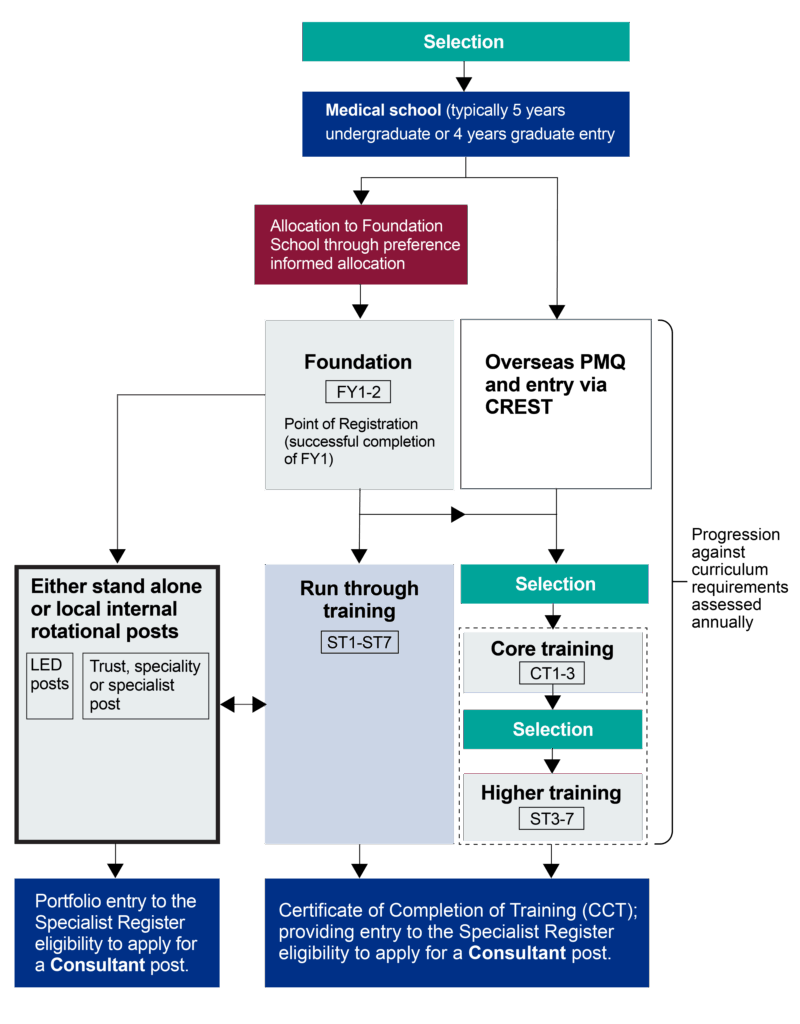

29. Postgraduate medical training is currently delivered through structured programmes that train in a stepwise progression from the point of qualification, through foundation and specialty programmes, to completion and entry onto the GMC Specialist Register or GP Register (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: GP training pathway

Figure 3: Specialty training pathway

30. The foundation programme provides a broad-based experience across 2 years with the point of full registration with the GMC at the end of year 1.

31. Specialty programmes have indicative durations (3 years for GP training, 6 or 7 years for other specialties) and may be designed as ‘run through’ with a single competitive entry point (usually for single specialty programmes such as paediatrics or obstetrics and gynaecology) or split into a core programme that acts as a general training programme and feeds into higher specialty programmes (such as core medical training followed by a medical specialty). The latter have seen increasing competition ratios for entry to both core and the higher specialty aspects.

32. Progression of the individual doctor is assessed through the Annual Review of Competency Progression (ARCP), mapped against specialty curricula, with delivery by the statutory education body (currently NHS England, at a regional level) led by a postgraduate dean.

33. The dean also holds the role of responsible officer for doctors in national training programmes, managing a resident doctor’s training and any professional standards concerns.

34. Quality of training and the learner environment is managed through NHS England regions and regulated by the GMC. It is important to note that resident doctors train while employed by a service-based employer (NHS providers, defence services and, in some cases, industry or local authorities), providing significant service delivery in tandem with their training.

Table 1: Organisational responsibilities in training

| Organisation | Role and responsibilities |

|---|---|

| General Medical Council (GMC) | – Sets standards for education and training, including recruitment and training delivery – Agrees specialty curricula – Defines the quality standards in training, support quality management of training sites and programmes and provide quality assurance – Provides the professional regulation of all doctors |

| Medical Royal Colleges and faculties | – Set specialty curricula and assessment tools (including collegiate examinations)Provide training portfolios – Design and agree recruitment and selection models with Medical and Dental Recruitment and Selection (MDRS)Support definition of quality standards in training – Provide education courses – Assessments for the portfolio route to specialist registration |

| NHS England acting as the statutory education body for England | – Designs and delivers training programmes at regional level for each specialty – Manages and supports the progression of individual doctors against the curriculum – Quality manages training programmes – Provides the responsible officer regulatory function for doctors in postgraduate training |

| NHS providers including independent and charity sectors providers Including GP practices and commercial training environments | – Deliver training through provision of placements and educational and clinical supervision, overseen by directors of medical education – Provides local support to doctors in both training and locally employed roles |

35. All specialty training programmes have an indicative duration. However, GMC standard and policy changes have resulted in a greater focus on training based on capabilities and skills acquisition; so, the completion time takes into account previous experience and the rate of achieving curriculum requirements rather than rigidly adhering to ‘time served’.

36. Iterative reforms by the statutory education bodies in all 4 nations and the Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans (CoPMeD), supported by the GMC and Royal Colleges and faculties, have improved the approach to capability-based training and access to both flexible working and training in the UK. The assessment process has meant the majority of residents still gain competencies at the indicative rate.

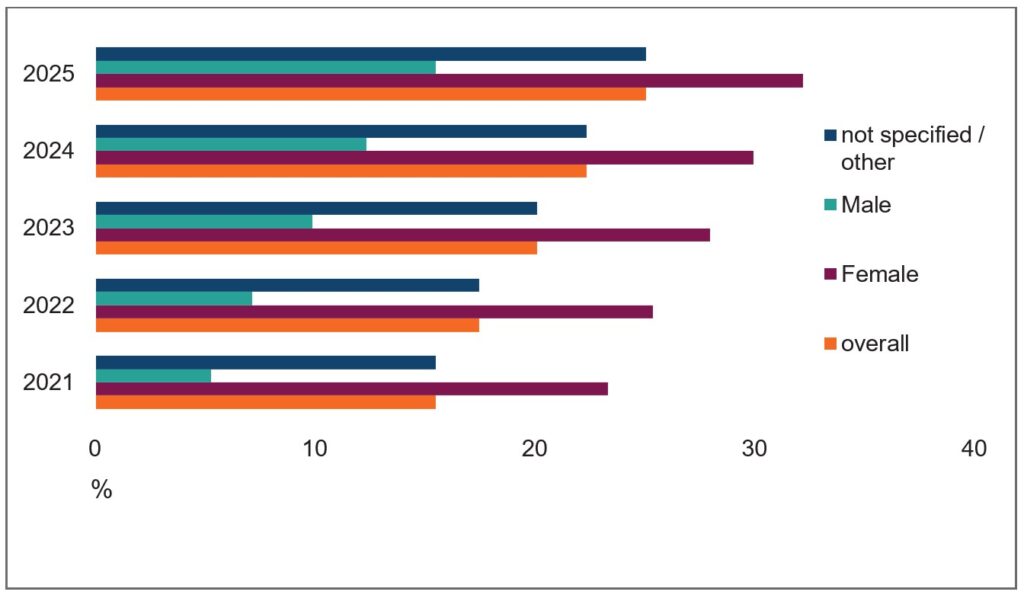

37. Flexibility in training. Resident doctors can apply to work flexibly (usually between 50% and 90% WTE) and take time OOP to pursue other experiences, some of which can count towards training progression, such as formal research. Overall, 25% of resident doctors currently train LTFT and over 4% are currently taking time OOP.

38. The significant increase in flexible training over the last 5 years is striking (Figure 4). However, while the proportion of male resident doctors working LTFT is increasing faster than for female resident doctors, the latter are still twice as likely to be working flexibly (32% compared with 16% in 2025).

Figure 4: Proportion of resident doctors training less than full-time overall and by gender, 2021 to 2025 (source: NHS England data)

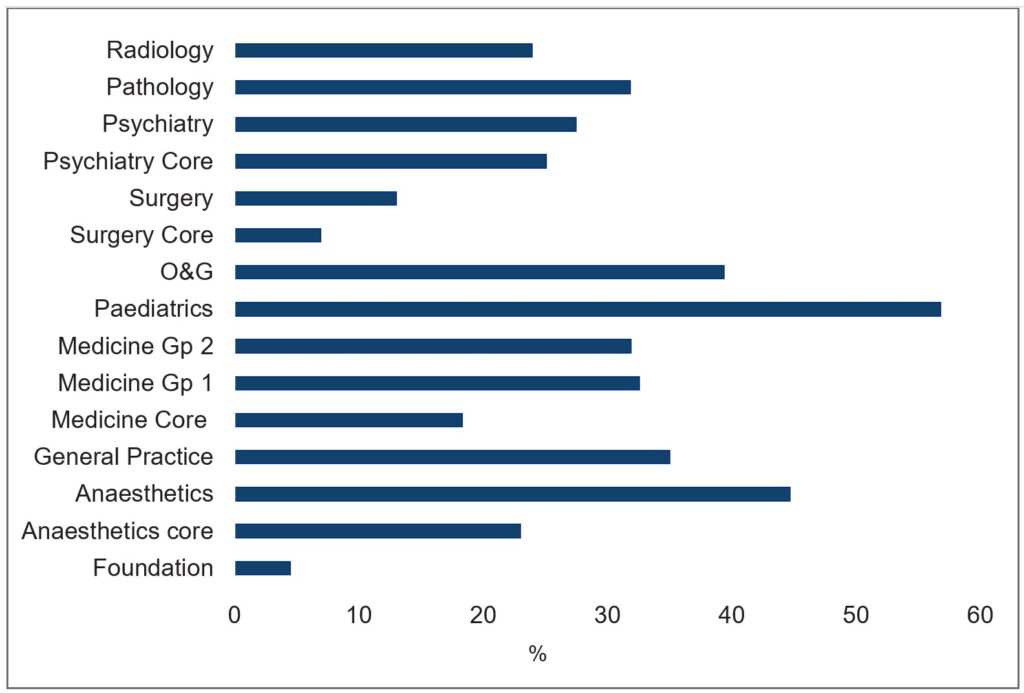

39. There is significant variation in the numbers training flexibly across specialties, with markedly fewer opting for this in foundation and surgical specialties, and significantly higher numbers in anaesthetics, paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Proportion of resident doctors training less than full-time by specialty cluster, 2025 (source: NHS England data)

1.4 Recruitment to training programmes

40. Recruitment to training programmes is managed nationally across the 4 UK nations.

41. Foundation years. Allocation of foundation year training posts has recently changed from a ranking based on performance to an approach based on an applicant’s geographical preference (preference informed allocation) after significant consultation with and the support of those affected, including medical students. This has helped align the geographical distribution of foundation doctors more closely with service needs and aims to support fairer allocation for individuals from deprived backgrounds. However, it has led to criticism that excellence is no longer valued.

42. GP, core and higher specialty training. Recruitment and selection to training programmes is managed across the 4 nations by the Medical and Dental Recruitment and Selection service (MDRS). The selection process is managed nationally using a variety of assessment tools defined by the specialty committees of the medical Royal Colleges and faculties in partnership with MDRS.

43. The GMC’s scope of regulation includes recruitment, focusing on equity of access and fairness of process.

44. The range of selection approaches is large, including machine marked situational judgement testing (the multi-specialty and recruitment assessment, MSRA), assessed application forms and multi-stage interviews.

45. Recent changes have included the removal of ‘paid for’ courses and additional degrees from scoring – focusing more on capabilities demonstrated to avoid discriminating against any group of applicants.

46. Recruitment application numbers are discussed in greater detail in section 1.6

1.5 Funding flows in postgraduate training in England

47. All resident doctors working with provisional or full registration with the GMC provide patient care while they are in training posts (with the exception of training rotations in GP settings, which are classed as supernumerary and therefore do not contribute to patient care).

48. Funding for the educational and training aspects of their role has been needed to ensure that doctors’ training posts are distributed across the country, the training is of suitable quality and residents can progress through their ARCP. This funding is administered by NHS England. It includes both a salary contribution towards the employment of doctors in training and funding for the educator time to support training and employment of those managing the training programmes (including the postgraduate deaneries).

49. Funding for most postgraduate medical training programmes is covered by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) guidance Education and training tariffs 2025 to 2026; posts in these programmes are commonly referred to as ‘tariff funded’. However, the 2025 to 2026 tariff guidance does not apply to GP (foundation and specialty placements in general practice), public health and palliative care specialty posts outside hospital and community health settings.

50. The tariff guidance sets out that eligible posts will attract a salary contribution according to the grade for each training post, as well as a contribution to the costs of the provider in respect of provision of clinical supervision, learning support, infrastructure and overheads, among other cost categories. NHS England makes these payments either directly to the employer of the resident doctor or via a lead employer arrangement For GP placements, GPs receive a trainers grant and support with educational costs like continuous professional development (CPD) for educators.

51. All resident doctors on a training programme (regardless of funding contribution) are eligible for study leave. There is an agreed national policy covering the eligible spend and processes and this budget is managed by NHS England. The agreement following the 2018 industrial action moved the funding model from a fixed per capita allocation to recognise that there was significant variation in need between specialties. Residents are also eligible for travel and relocation cost reimbursement, which again is managed nationally.

52. In addition to the above costs, funding for which is passed to training providers, NHS England funds the costs of local postgraduate deaneries, including training programme directors and education support teams.

1.6 The case for change: competition for training places

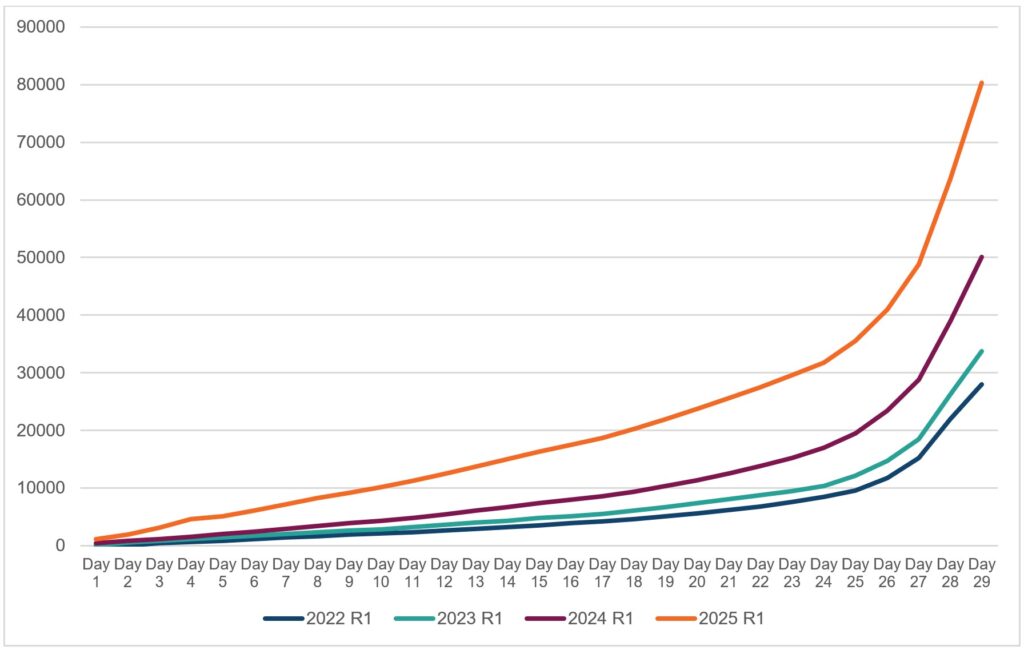

53. Changes in 2019 to the shortage occupation list to include doctors has resulted in significant increases in the numbers of overseas medical graduates applying for UK training posts. Coupled with the incremental growth in the number of medical degree places in England, this has resulted in marked increases in the numbers of applications for the majority of core and specialty training programmes (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Increase in applications during round 1 by year, 2022–2025 (source: NHS England data)

54. From a service perspective, in the short term this may have been beneficial as many specialty training programmes now have fill rates of 100%. However, some specialties, such as clinical and medical oncology and genitourinary medicine, still have significant underfill and programmes outside the major urban areas are considered less popular by applicants, reducing the likelihood of recruiting to posts in remote, rural and coastal localities.

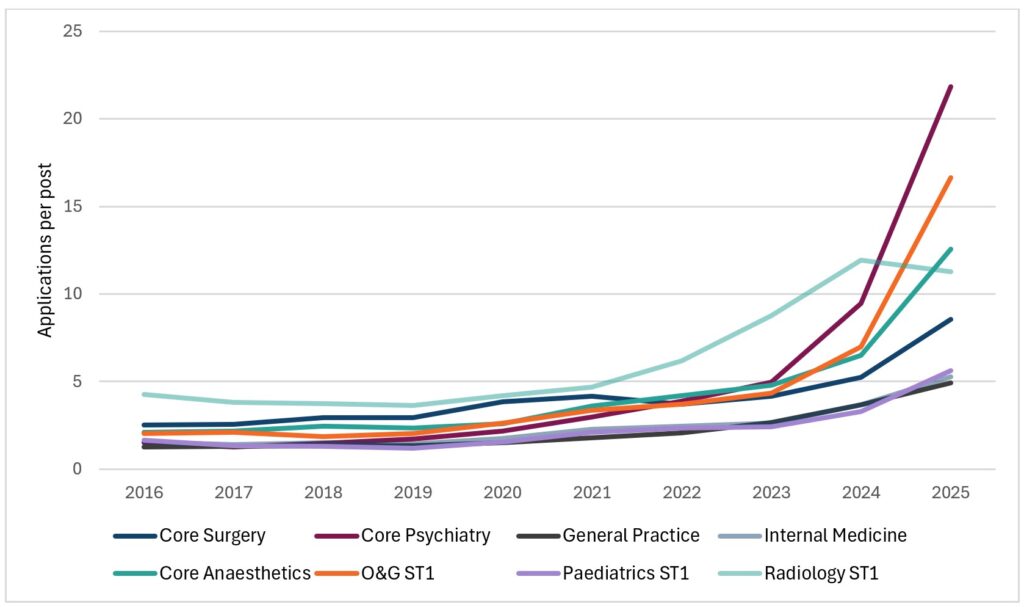

55. Nonetheless, competition ratios for core and higher training have increased for the majority of programmes. This has driven candidates to apply for more than one and in some cases multiple programmes, further driving up competition (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Core training competition ratios, 2016–2025 (source: NHS England data)

56. Planned increases have been made to the numbers of training programmes in response to the NHS Long Term Plan, cancer, diagnostics and acute specialties in the last 6 years (Table 2). These additional posts have also been geographically distributed based on population health need, which has facilitated targeted increases in under-doctored areas. These targeted expansions have not, however, met the corresponding demand for training posts.

57. GP specialty training (GPST) expansion. Since 2015, according to NHS England recruitment data, GPST recruitment in England has increased year on year, reflecting a sustained effort to grow the general practice workforce. Over this period, fill rates have also improved markedly – from 88.8% in 2015 (with regional variation as low as 61.9% in the North East) to 99.8% in 2023. Alongside this growth, general practice training has become increasingly competitive: the number of applicants per post has nearly doubled, from 1.4 in 2015 to 2.7 in 2023.

58. However, improvements in fill rates have been largely driven by applicants holding non-UK PMQs; they accounted for 73% of all applications in 2023. Consequently, international medical graduates now represent a significant proportion of the GP training pipeline – 50% of those accepting a training place in the same year.

59. Attrition from GPST remains low. Between the 2016/17 and 2022/23 academic years, the average annual attrition rate was 1.7% (NHS England internal data). It is important to note that this figure reflects those leaving GP training specifically and not necessarily departure from the wider medical workforce.

60. Recent training reforms have also reshaped the structure of GPST. Trainees now spend two-thirds of their programme in general practice placements, up from half previously. Within these placements, according to National Education Training Survey Results in 2023, trainees report that about 40% of their time is dedicated to ‘pure training’ – that is, structured learning, distinct from service delivery, which is significantly more than is reported in secondary care settings.

61. GMC 2025 national training survey data indicates that trainers in secondary care are significantly more likely than those in general practice to report being unable to use allocated training time as intended, with rota gaps and service pressures frequently compromising education.

62. GP trainees work alongside their GP trainers in GP settings, with protected time for hot case reviews, case-based learning, reflective practice and tutorials. They have a statutory half-day release programme every week, often with GPSTs from a vocational training scheme meeting up to share learning.

Table 2: Number of doctors in training posts as recorded by the GMC in the UK, 2017–2023 (source: GMC reference tables for doctors in training)

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation training | 14,793 | 14,880 | 15,188 | 15,454 | 15,647 | 16,270 | 17,414 |

| General practice | 11,295 | 12,049 | 12,902 | 13,905 | 15,090 | 15,933 | 16,302 |

| Core training | 7,828 | 8,189 | 8,364 | 8,483 | 10,238 | 10,898 | 11,246 |

| Medicine | 6,756 | 7,130 | 7,388 | 7,602 | 7,105 | 7,354 | 7,623 |

| Surgery | 4,171 | 4,306 | 4,327 | 4,268 | 4,405 | 4,416 | 4,554 |

| Paediatrics and child health | 3,749 | 3,870 | 3,881 | 4,013 | 4,088 | 4,179 | 4,371 |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 2,176 | 2,286 | 2,397 | 2,439 | 2,501 | 2,570 | 2,672 |

| Anaesthetics | 2,698 | 2,755 | 2,808 | 2,871 | 2,952 | 2,619 | 2,649 |

| Radiology | 1,787 | 1,896 | 1,983 | 2,084 | 2,269 | 2,397 | 2,481 |

| Emergency medicine | 1,527 | 1,599 | 1,749 | 1,874 | 1,813 | 1,786 | 1,856 |

| Psychiatry | 1,225 | 1,261 | 1,312 | 1,371 | 1,453 | 1,580 | 1,774 |

| Pathology | 699 | 671 | 711 | 755 | 807 | 865 | 854 |

| Ophthalmology | 663 | 675 | 681 | 680 | 700 | 710 | 727 |

| Intensive care medicine | 233 | 321 | 312 | 477 | 516 | 563 | 649 |

| Public health | 190 | 246 | 275 | 276 | 303 | 313 | 347 |

| Sexual and reproductive health | 29 | 33 | 37 | 41 | 46 | 54 | 56 |

| Occupational medicine | 32 | 33 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 27 | 25 |

| Total | 59,851 | 62,200 | 64,342 | 66,621 | 69,962 | 72,534 | 75,600 |

1.7 The case for change: the changing shape of the medical workforce

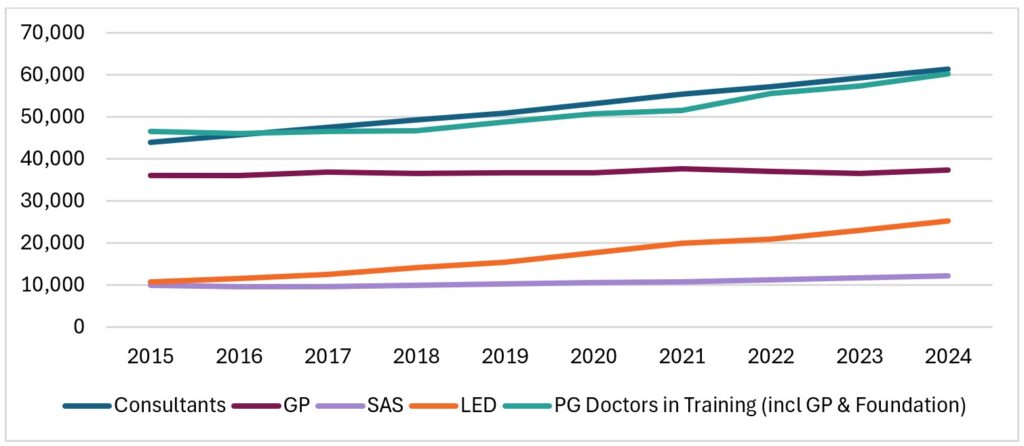

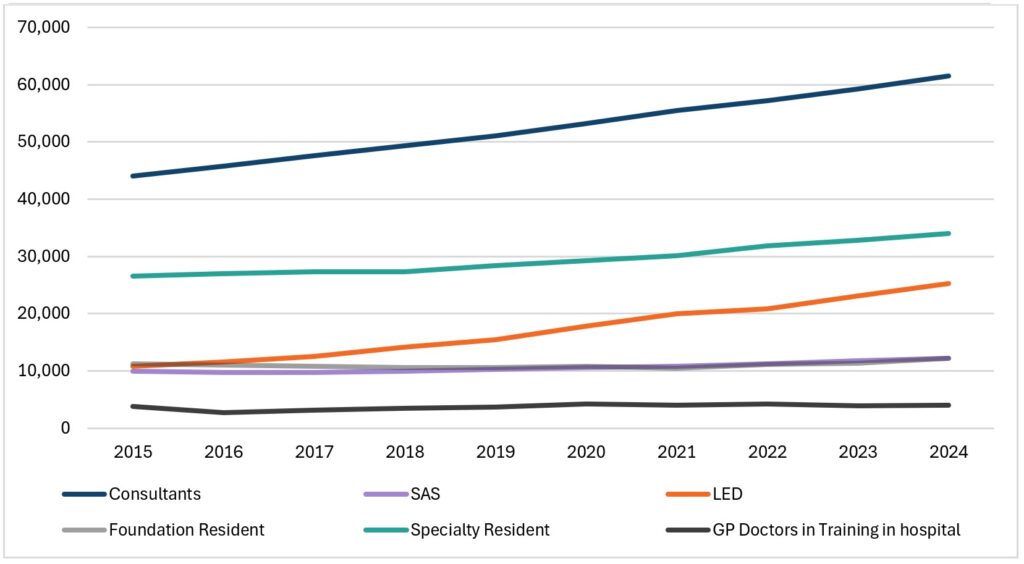

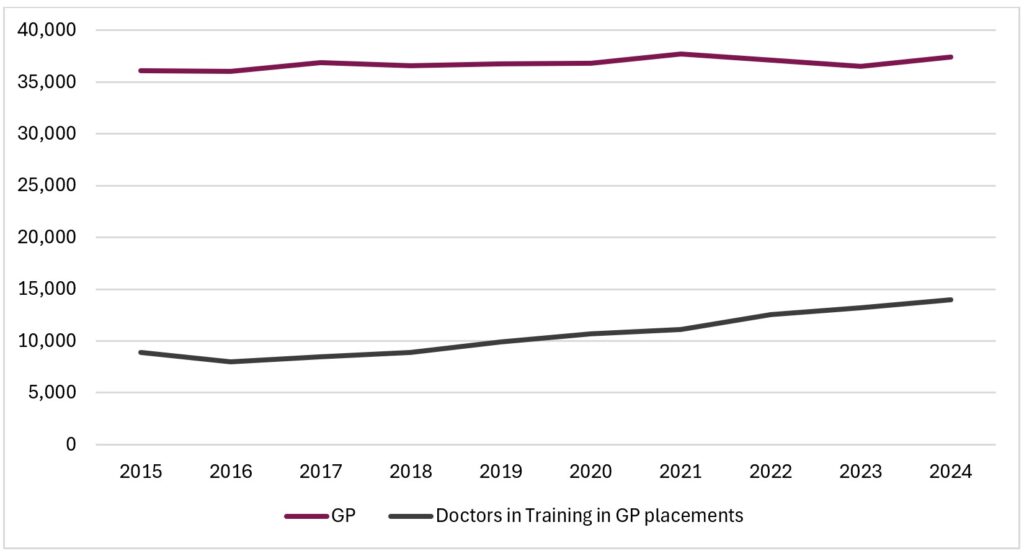

63. The size and make-up of the medical workforce in England has changed significantly over the last decade, with significant increases in the numbers of consultants and LEDs (figures 8–10). The number of WTE GPs has not increased significantly, although the planned increase in GPSTs over the last 4 years has started to impact on this and will continue to do so.

Figure 8: Number of doctors working in the NHS (hospital, community health and primary care) by role, 2015–2024 (source: NHS England data)

Figure 9: Number of doctors working in secondary care (hospital, community health) by role, 2015–2024 (source: NHS England data)

Figure 10: Number of doctors working in primary care by role, 2015–2024 (source: NHS England data)

64. Locally employed doctors (LEDs) is a catch-all term for doctors employed by an NHS trust under locally negotiated contracts. LEDs may be referred to by various titles, such as trust grade, clinical fellow, foundation year 3 or staff grade. Posts are often temporary and usually at ST1–3 grade. This group are not in a formal training or development programme, with any support provided dependent on the approach of their employing organisation. NHS England does not hold responsibility for these doctors; however, national and regional work has supported the development of this group where possible.

65. LEDs can be found across most specialties, and they play a vital role in the medical workforce, with diverse backgrounds and skills.

66. In 2023, over 77% of UK doctors completing foundation year 2 in England do not or cannot progress directly into core training (GMC Education data tool, 2024). Instead, many take up LED roles or choose to work abroad for a time. While a variety of reasons are given for this, such as seeking career opportunities, taking a break from formal training or taking time to make career decisions, the increasing competition for selection to a specialty training post is cited as being a key driver for many taking this route (UK Foundation Programme Office F2 career destinations survey report, 2024).

67. The current structure of training effectively means that a newly graduated doctor has to consider how best to gather evidence to support an application to specialty training and meet the core person specifications. Uncertainty about future careers and the need to develop a competitive portfolio are cited as key reasons to take up a LED post after foundation year 2.

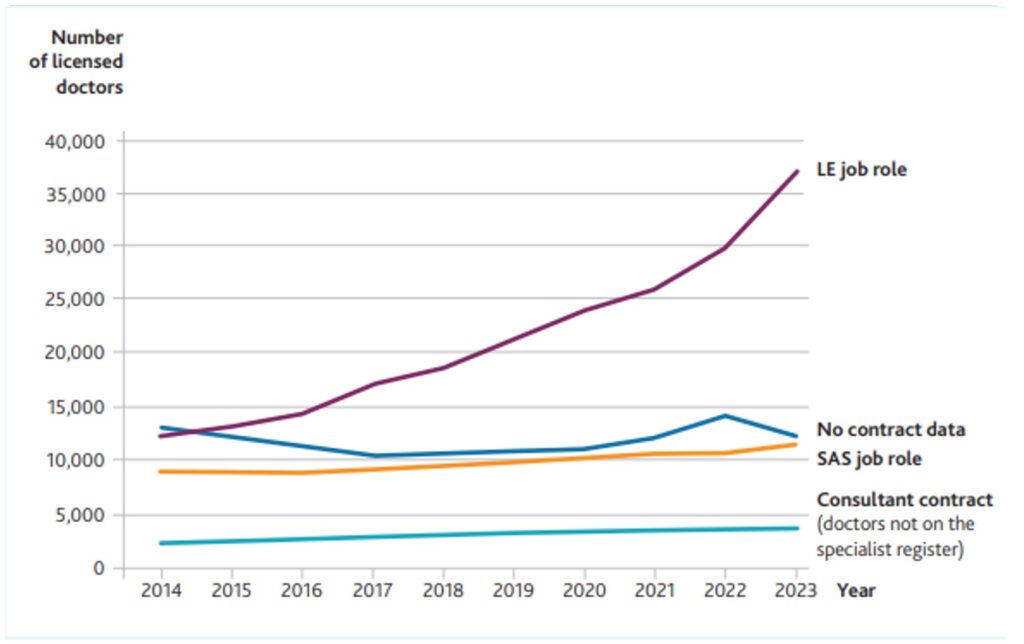

68. This interplay of factors has resulted in a substantial increase in the numbers of LEDs (Figure 11). According to the GMC’s workforce report 2024, there were 36,831 LEDs in England and Wales in 2023, a 75% increase since 2019.

Figure 11: Licensed doctors on neither register and not in training working in England and Wales, by NHS contract job role, 2014–2023 (source: GMC Workforce report 2024)

69. Specialist, associate specialist and specialty (SAS) doctors. Prior to 2008, SAS doctors were appointed to staff grade or associate specialist posts. Since 2008, all new SAS appointments have been as specialty doctors. From 2021, a new specialist grade role was introduced that offers career progression for specialty doctors.

70. The route to a substantive post for this group is through appointment to a trust specialty or specialist post, depending on the level of postgraduate and specialty experience of the doctor.

71. The GMC portfolio pathways (previously CESR and CEGPR) are the primary routes for these doctors to join the Specialist Register or GP Register and take up a consultant or GP post. However, there is currently limited flexibility to move this group of doctors into training programmes to allow the development of specific capabilities. Previous initiatives, for example the SAS development fund, aimed to support doctors on the portfolio pathway, but uptake has been limited

72. The number of doctors in this group has gradually increased (Figure 11) and their roles have extended to more formally include leadership, educational supervision and quality improvement, recognising their fundamental contribution to the provision of healthcare.

73. The career support and professional development of these doctors remain with their employer, with some support through NHS England SAS tutor funding.

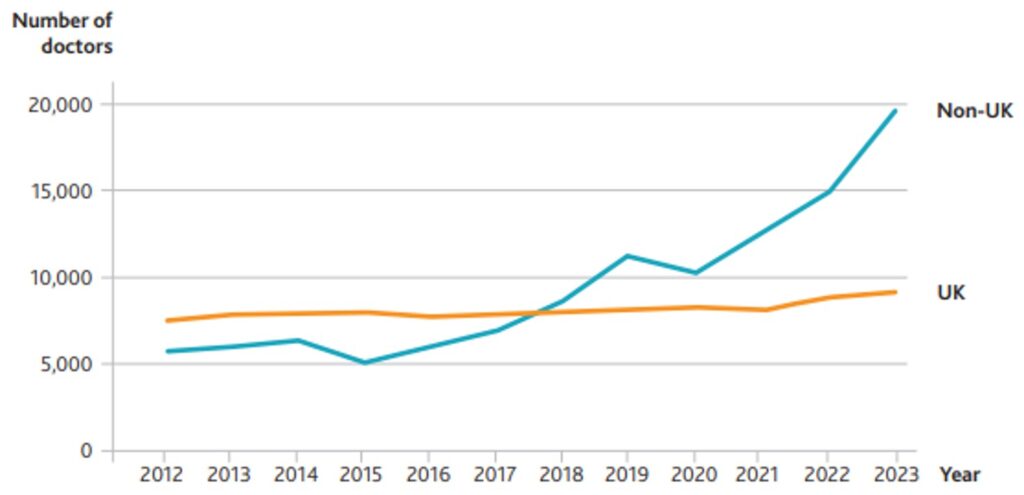

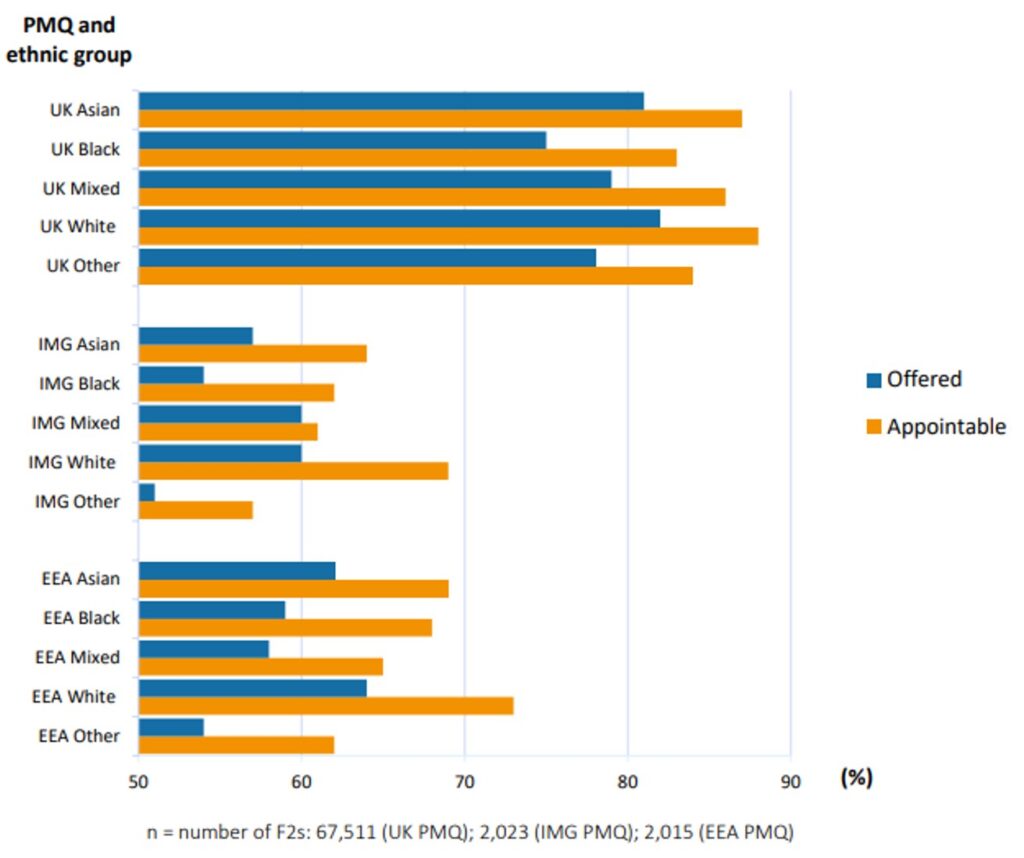

74. International medical graduates (IMGs). While the number of doctors joining the workforce who gained their PMQ in the UK has gradually increased over the last decade, the number who qualified outside the UK has increased very significantly (Figure 12).The proportion of new joiners to the medical register who attained their PMQ overseas increased from 47% in 2017 to 68% in 2023 and IMGs filled 66% of LED roles and 81% of SAS roles in 2023.

Figure 12: Doctors joining the UK workforce by PMQ region, 2012–2023 (source: GMC Workforce report 2024)

75. As described above, this is largely the result of changes to the shortage occupation list in 2019. However, this trend started before 2019 and reflects the increased service needs in secondary care and changes to working hours regulations, with IMGs significantly over-represented in LED posts.

76. There is significant variation in the proportion of IMGs between training programmes, from 4% in public health to 52% in GP training (Table 3). Overall, the proportion of doctors in training programmes who attained their PMQ overseas UK rose from 18% in 2019 to 27% in 2023.

Table 3: Proportion of non-UK graduates in training programmes (source: GMC Workforce report 2024)

| Programme | 2019 | 2019–2023 % point change | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthetics | 8% | 3 | 11% |

| Core training | 20% | 7 | 27% |

| Emergency medicine | 24% | –2 | 22% |

| Foundation training | 5% | 3 | 8% |

| General practice | 34% | 18 | 52% |

| Intensive care medicine | 10% | 10 | 20% |

| Medicine | 23% | 9 | 32% |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 21% | 6 | 27% |

| Ophthalmology | 10% | 4 | 14% |

| Paediatrics and child health | 20% | 9 | 29% |

| Pathology | 22% | 9 | 31% |

| Psychiatry | 29% | 10 | 39% |

| Public health | 2% | 2 | 4% |

| Radiology | 14% | 5 | 19% |

| Surgery | 14% | 5 | 19% |

| Total | 18% | 9 | 27% |

1.8 The case for change: current and future population health challenges

77. The changes in population health needs and imbalances in the provision of care in England are well documented in the annual Chief Medical Officer reports and Office for National Statistics datasets.

78. The changing population demographic and life expectancy. The NHS and wider health and care services in England face significant challenges in meeting the health and care needs of both the current and future population. This is an ageing population, more markedly so away from large urban centres in rural, remote and coastal areas, a trend that is projected to continue (ONS Subnational population projections for England, 2020 and ONS Population estimates for the UK, England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, 2024).

79. While our population is living longer and many are living more years in good health, reflecting advances in medicine and public health, the number of older people living with multimorbidity and frailty is also increasing (Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2023: health in an ageing society).

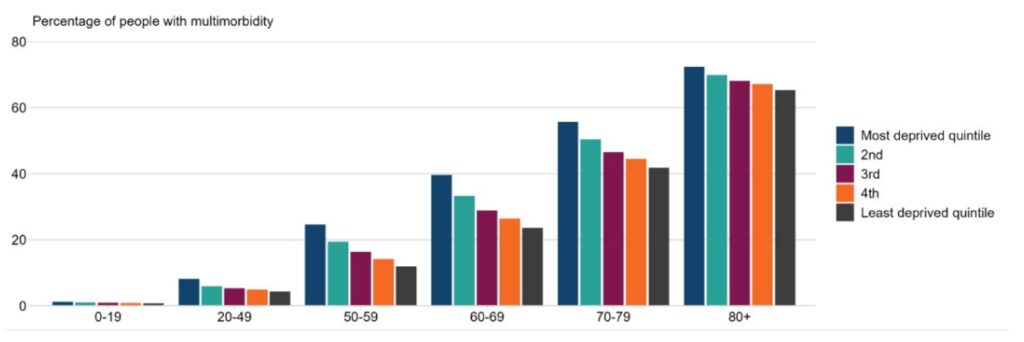

80. While data from 2020 shows that multimorbidity increases with age, its also shows that its prevalence in England is higher in more deprived areas, especially in younger age groups (Figure 13).

81. Health trends and variation in England, 2025 shows that life expectancy is 10.4 years lower for men and 8.4 years lower for women in the most deprived parts of England compared with the least deprived parts.

Figure 13: Prevalence of multimorbidity (2 or more conditions) by age and deprivation (Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles) in England, 2020 (source: Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2020: health trends and variation in England)

82. The contribution of ‘general capabilities’ and ‘specialist skills’ to improvements in life expectancy. The longstanding incremental reductions in mortality from key diseases are the result of earlier detection, improved efficacy of interventions and improved secondary prevention. As well described, this requires a mix of specialist input and, notably for detection and secondary prevention, generalist capabilities. This mix is increasingly important in enabling doctors to manage growing multimorbidity ageing population. There is a need for doctors and the multidisciplinary teams in which they work to shift – and have the skills to do so – from provision of care on a ‘disease by disease’ basis to management of an individual’s related diseases, particularly in older patients. It is possible for a doctor to become a specialist while retaining the generalist skills needed to treat patients with multiple diseases.

83. Provision of healthcare resource in deprived, remote, rural and coastal communities. There are clear disparities in the numbers of doctors in postgraduate training, consultants and nurses between urban and non-urban communities, despite reforms aimed at targeting the growth and development of the workforce in these areas (Chief Medical Officer’s annual report 2021: health in coastal communities). This is, in part, due to the location of secondary and tertiary NHS hospitals but exacerbated by smaller peripheral hospitals struggling to recruit and retain staff compared with those in larger urban centres. Imbalance is also seen in primary care, with patients per GP highest, and increasing most rapidly, in the most deprived areas. The development of new medical schools in these areas in 2017/18 was designed to support the development and retention of a local medical workforce. Subsequent increases in medical school places, both as planned expansion and as a result of the pandemic’s impact on A-levels – have further increased the numbers of future graduates. While early data suggests doctors wish to train locally, the training infrastructure beyond the foundation programme is often insufficient to support the emerging need.

84. Demand for care, waiting times and waiting lists. There has been a very significant increase in demand for healthcare over the last 2 decades. This, coupled recently with the loss of significant planned activity during the Covid-19 pandemic, has led to an increase in the number of patients waiting for diagnostic tests from 800,000 in 2006 to 1,600,000 in January 2025 (NHS England monthly operational statistics, March 2025). The number waiting more than 6 weeks peaked at 500,000 in 2023 but was around 320,000 in January 2025 following a 0.9% increase in diagnostic activity over the preceding 12 months.

1.9 The case for change: supporting the 10 Year Health Plan

85. Workforce is one of the biggest challenges facing the NHS and one of the most important enablers in successfully delivering the reforms and ambitions described in the 10 Year Health Plan for England: fit for the future.

86. The support of the medical profession will be critical to achieving the vision of the 10 Year Health Plan and the 3 key shifts that underpin it: moving care out of hospitals and into communities; making better use of technology; and a greater focus on preventing illness.

87. The focus on neighbourhood health and out of hospital care will require the harnessing of the collective expertise of specialists, primary, community and mental health practitioners, hand in hand with local communities, to transform health and care services. There are examples of well-developed local models of integrated care in psychiatry and psychological health services, geriatrics, palliative medicine, diabetes, respiratory, cardiology and musculoskeletal services. However, for these to be scaled up, training programmes will need to be designed around services located in these settings, which means rotations and access to high quality educator capacity must be a central consideration in the development of neighbourhood services.

88. Similarly, doctors will need skills to lead change, work effectively within and lead multidisciplinary teams, better understand the needs of their communities and contribute more meaningfully to preventative care. These capabilities should be key considerations in future changes to undergraduate education, postgraduate training and curricula.

89. With the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) as well as asynchronous patient consultations and advice, for example advice and guidance via the NHS App, the resident doctor will need to be trained in how to manage the patient without ever having met them in person. Doctors will need to be enabled to effectively use digital systems and new technologies that support future ways of delivering care, for example in group digital consultations.

1.10 International comparisons

90. Many countries follow similar models to UK training, often based on historical relationships.

91. The key variations include:

- while undergraduate programmes are by far the most common level of education at the point of entry into formal medical training, some countries (notably the USA and Canada) require a bachelor’s degree (usually science based) prior to entry to a graduate medical programme

- while the UK primarily has 3 stages in training programmes (foundation, core and higher), other countries use residency programmes of 1–2 years followed by fellowship training in a subspecialty (for example, the USA) or longer residencies (for example, 2–7 years in Canada) depending on the specialty. Australia follows a similar model to the UK (1 year internship, 1–2 years residency and 3–7 years registrarship)

- the requirement for a period of general postgraduation training prior to entering a specialty programme also varies, with foundation programmes in the UK and general residencies in Australia and some other Commonwealth countries being a requirement. This is not a requirement in Canada and the USA; however, residencies are of a more general nature in these systems with specialisation taking place at fellowship level

92. The role of educational organisations and regulators also varies internationally: independent ‘Royal College’ structures in the UK and Australian systems are empowered to provide the assessment and completion requirements for specialty training, while in the USA system the assessment role is managed by specialty boards (doctors become ‘board certified’ to practise independently).

93. European section and board examinations that assess and certify the knowledge and skills of doctors are the required standard across the European Union and facilitate movement between countries.

94. Recruitment to training. Multiple models of selection exist post-graduation:

- the USA and Canada use a national matching system based on employer and applicant preference to recruit to their resident programmes

- Australia uses a state-run merit-based system using candidate preferences

- almost all comparable healthcare systems use a meritocratic process to some extent

- the degree to which future workforce need determines the numbers of specialty training posts varies significantly, with most healthcare systems basing the numbers on individual provider recruitment rather than limiting these nationally, as is done in the UK. While the UK’s approach has certain advantages, it can result in some specialties and geographies having a dearth of resident doctors and significantly increase the risk of career bottlenecks at entry into the consultant or attending grade

95. Competency versus time-based training:

- several countries – notably Canada, the USA, the Netherlands and Australia – have moved formally to competency-based medical education, a model being adopted in the UK

- this uses assessment and college, faculty or board examinations to determine progression and completion, rather than being entirely or significantly time-based training

96. Training to population need rather than specialty:

- the unique needs of populations distant from major centres has challenged the delivery of postgraduate medical training within specialty silos

- the most well-established model for this is the Australian remote and rural programme that allows a clinician to develop the required skills in surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology and anaesthesia alongside traditional general practice to manage patients to a higher degree of specialism than a GP could alone

97. Transferability of capabilities between specialties:

- training aligned to a college or board specialty curriculum can be seen as a block to moving between specialties while in training. Some models, such as Canada, allow for a modular approach to training, with some modules being common across a wide specialty range, facilitating movement between training ‘tracks’; however, this model is in its early stages of development

- these modular models nominally allow a doctor to practise with relative independence in one part of their scope of practice while continuing to train in another area of their specialty

1.11 The challenge of change: the need for trade-offs

98. Postgraduate medical training is complex and there is an inevitable requirement to manage trade-offs when making changes to its delivery. For example, we heard that some resident doctors are unhappy with the frequency, length and locations of their rotations, while others are happy with current rotational arrangements. Similarly, to address the under provision of doctors in specific communities and services, training posts have been preferentially expanded in ‘under-doctored’ areas, but more posts may need to be moved. This is particularly pertinent to remote, rural and coastal locations and to specialties such as geriatrics and genitourinary medicine.

99. There are tensions between the need to provide a medical workforce to meet population health needs and the personal and professional autonomy doctors have asked for. Similarly, tensions exist in achieving the balance between the greater flexibility that some doctors want and the ask for certainty about placements across their training programme.

100. Improving medical education requires a multifaceted, multi-agency effort, focused on the quality, efficiency and relevance of training for our future doctors. This will require changes to undergraduate and postgraduate education, addressing issues to improve training opportunities for doctors at all stages of their career, as well as the misalignments between the distribution of doctors and the needs of communities.

101. There are significant areas of overlap between the needs of patients, communities, healthcare systems and the individual doctor (Table 4) as well as the tensions between them, and recognition that the individual asks of doctors may be mutually incompatible – for example, the desire for flexibility in training and the ability to step in and out of a programme makes it challenging to provide certainty of future placements.

Table 4: Tensions in postgraduate medical education and training

| Services, patients and communities | Both | Individual doctor |

|---|---|---|

| – Geographical distribution of workforce based on population – Understanding of local population health need – Accurate workforce planning to determine future need – Short and longer-term solutions to delivering the required workforce – Skills and capabilities matched to population need | – Quality assurance of the training process and the doctor – Adequate posts and applicants – Effective and fair recruitment, allocation and rostering | – Autonomy of choice of specialty and location – Flexibility within work and training – Desire to be a ‘specialist’ expert – Reduction of training bottlenecks – Simplification and greater autonomy of training and work processes |

102. Many doctors perceive a more generalist approach to training as undermining the desire and patient need for subspecialty expertise, while this will be fundamental for meeting the care needs of our current and future populations.

Chapter 2. What we have been told

2.1 Our approach to listening

1. The review has followed a profession-led model to hear the opinions of resident doctors, locally employed doctors (LEDs), specialist, associate specialist and specialty (SAS) doctors, consultants and GPs, clinical faculty, service providers, patients, the independent sector, charities and voluntary organisations. We have also engaged with key stakeholders and representative bodies and with the devolved nations (Appendix A).

2. We are extremely grateful to the many thousands who have participated in our listening events, responded to our call for evidence or contacted us directly. The response has been substantial and wide ranging and has allowed us to formulate our recommendations with the advice of a very wide range of medical and patient voices.

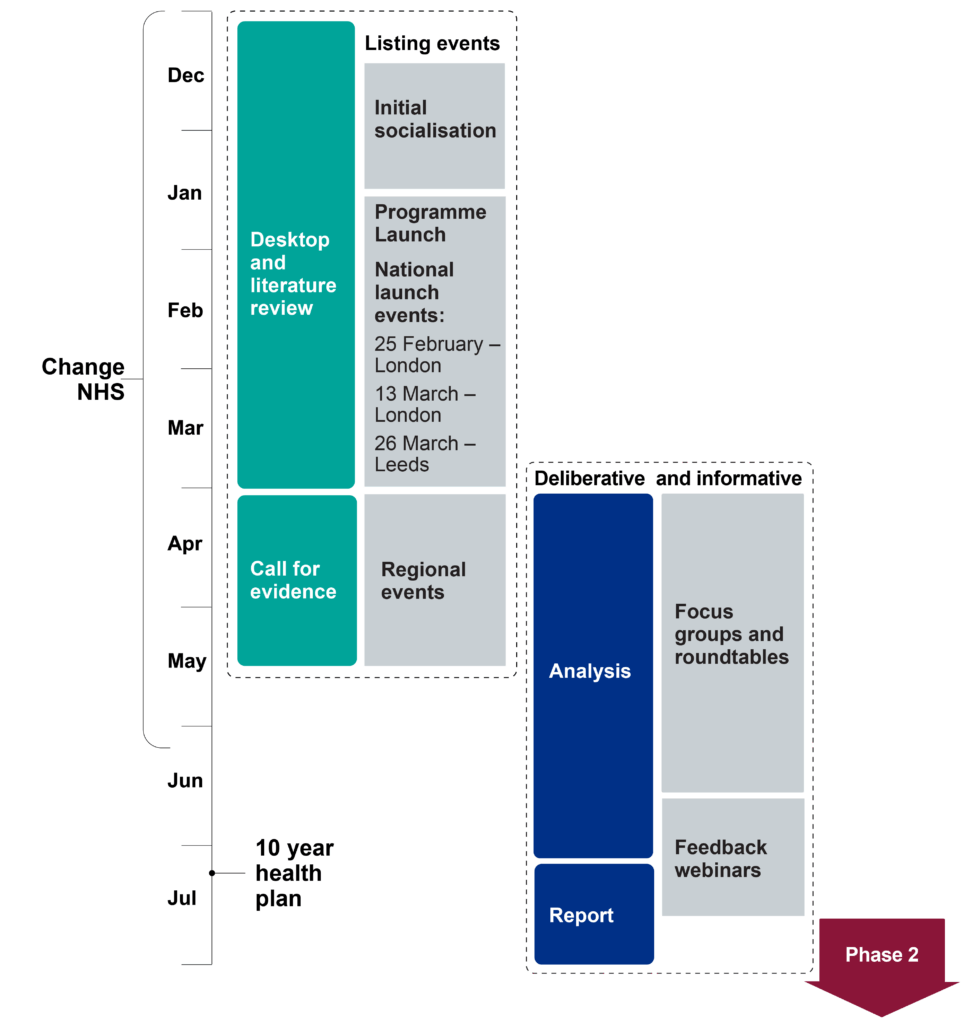

Engagement (Figure 14) has been undertaken through:

- a call for evidence and survey of priorities that:

- ran for 6 weeks

- received over 7,000 responses and 30,000 free text comments or evidence submissions (respondents in Appendix B, results in Appendix F)

- a literature review and desktop review of:

- published data

- unpublished work shared through the call for evidence

- the approach to postgraduate training taken by healthcare systems in other countries (Appendix C)

- national and regional engagement events (Appendix D and Appendix E)

- 23 round table events and focus groups (Appendix G)

- 2 ‘wrap up’ webinars to test what we heard and consider priorities for future work

Figure 14: Medical Training Review: Phase 1 diagnostic programme timeline

3. In describing the review findings, we recognise that there is significant overlap between the underlying drivers across a range of themes and outcomes. Summarising our findings risks losing some of the rich detail we have been given. The more detailed reports for each aspect of the review are presented in the appendices.

2.2 How we analysed the information

4. In reporting on what we heard, we brought together everything we heard through engagement and the findings from our background research.

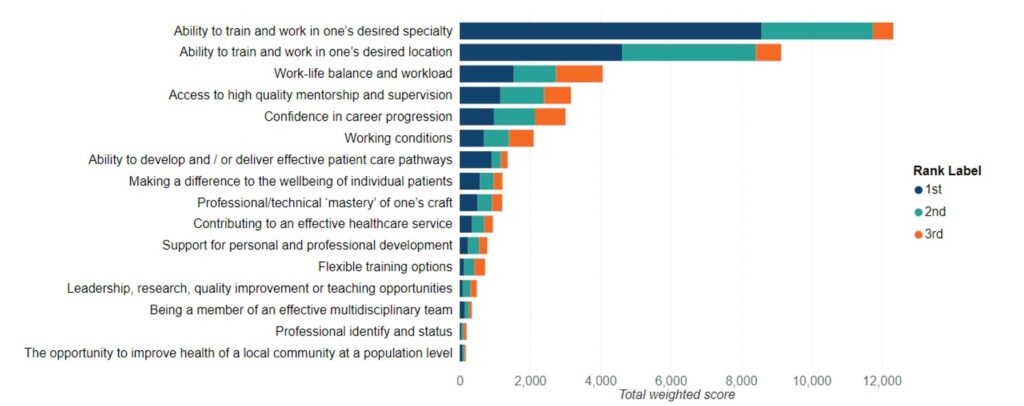

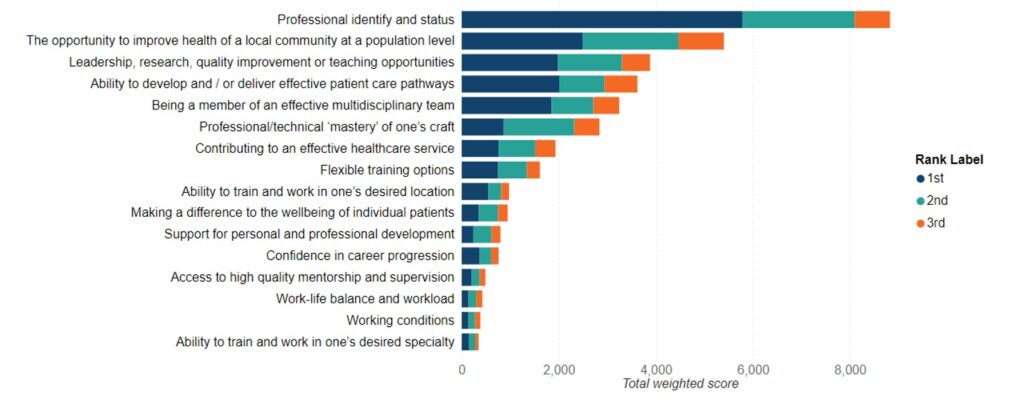

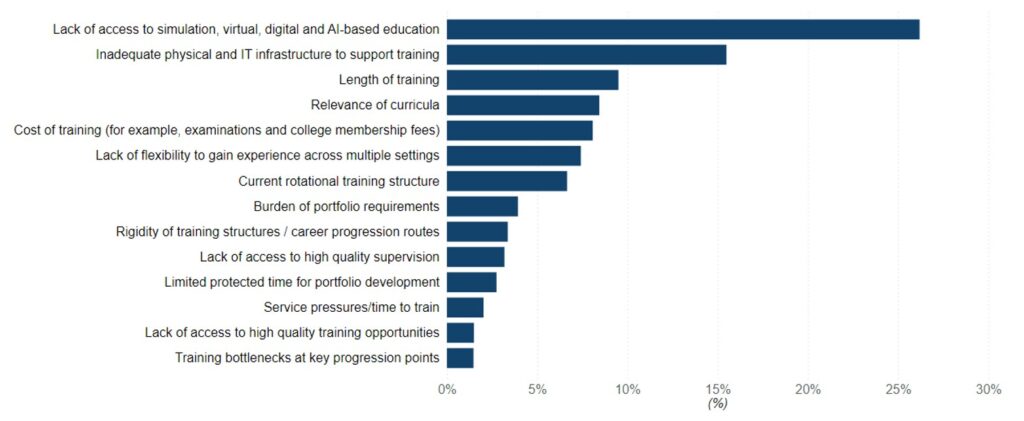

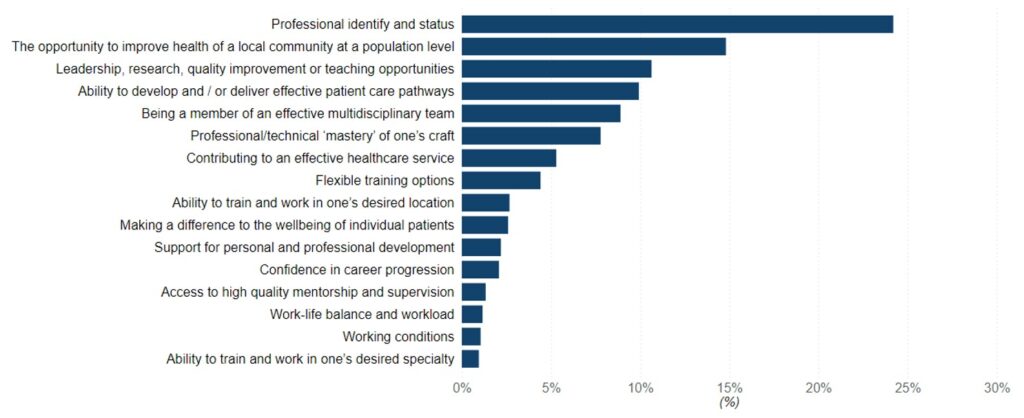

5. The call for evidence quantitative data enabled us to identify the most and least important factors raised by respondents for a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway (Figures 15 and 16). Coding of qualitative feedback submitted in the call for evidence enabled theming and analysis. The following narrative contains data drawn from both qualitative and quantitative analyses.

Figure 15: Most important factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of factors based on stakeholder preferences

Figure 16: Least important factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted ranking of factors based on stakeholder preferences

Review themes

6. We analysed the findings to identify emergent themes across all engagement channels and triangulated them against the literature review and desktop review to develop a consolidated matrix.

7. The emergent themes (Table 5) detailed in this chapter from section 2.4 onwards are prioritised according to strength of supporting evidence – that is, those most frequently cited by stakeholders across engagement channels are given highest priority.

8. We heard similar themes from most respondents, but with different emphasis. The comparison of views by respondent group can be found in Appendix I, but, broadly, the views of undergraduates and resident doctors, including LEDs, largely align.

9. For clarity, we have separated the information relating to those in national training programmes from that relating to those in LED and SAS posts. There are, however, many themes that cut across all groups of doctors.

Table 5: Emergent themes

| Training delivery and individual autonomy | – Access to training and factors impacting on progression – Rotation instability – Personal agency, flexibility and bespoke training – Challenges for specific groups, for example craft specialties, protected characteristics |

| Training factors | – Faculty development: supervision, mentorship – Access to training opportunities – Protected time for education and self-development – Training quality versus service demands – Fairness and support for doctors including LEDs |

| Training content | – Generalist competence and specialty skill development – Preparedness for transition points – Digital readiness and data literacy – Community-based training and public health alignment – System literacy and understanding broader NHS functions |

| Training routes and role progression | – Skills expansion post-CCT and recognition of extended capabilities – Training routes and alternative career pathways – Support for international medical graduates (IMGs)Progression and pathways for clinical academics |

2.3 Retaining and promoting best practice

10. Much of UK medical training is recognised to be of a high standard. Throughout the review we heard and noted the positives about training to ensure that we do not lose sight of these in any future changes. Although we heard very clearly the significant concerns of resident doctors, educator faculty and stakeholders, it is important to note there was also recognition and, on balance, support for much of UK training, and a recognition it is of high quality and delivered effectively in many places:

- nationally consistent training pathways with standardised curricula, ensuring common standards for those completing training

- robust management of the quality of training at all levels

- extensive clinical experience (over 10,000 hours)

- close supervision and support

- rotational training providing a variety of experiences

- a commitment to improving fairness, diversity and inclusion at recruitment and within training

- flexibility both of working patterns and the ability to take time out of training

- a funded study leave model to gain capabilities outside a training placement

- an integrated academic training programme sitting alongside clinical training pathways that is unique to the English training model

11. This narrative and feedback was particularly prominent from doctors whose initial training was outside the UK.

12. These positive aspects of the current system are also supported by the GMC 2025 national training survey with 84% of respondents saying the quality of experience in their post was good or very good (with a survey response rate of 70%).

The rest of this chapter summarises the key areas of the evidence gathered across the breadth of the review and is structured to align with the key themes identified in the analysis.

Sections 2.4–2.7 consider barriers to rewarding and satisfying postgraduate training for resident doctors; sections 2.8–2.11 the experiences of LED and SAS doctors, sections 2.12–2.14 the experiences of IMGs and section 2.15 recruitment and selection.

2.4 Resident doctors: training delivery and individual autonomy

Access to training and factors impacting on progression

13. A dominant theme in the desktop review was the mismatch between workforce needs and training capacity. Despite the UK undertaking planned and targeted expansions in the medical workforce, training bottlenecks represent a continuing concern for resident doctors and medical graduates. The increasing applications for finite training posts outlined in section 1.6 was also reflected in the desktop review and feedback. The Royal College of Physicians (RCP) notes that only 1 in 4 applicants to internal medicine training currently secures a training post – telling us that “thousands of UK doctors every year are unable to continue their medical career in an NHS training post” due to limited slots.

14. Increasing competition means many qualified and competent doctors have no alternative but to step into LED roles, often with limited development support. Royal Colleges and others have called for a long-term commitment to expand training numbers in line with population health needs.

15. This concern was also noted through the call for evidence (Figure 17) and engagement events, with a clear theme expressed by both individual resident doctors and stakeholders that the development of ‘bottlenecks’ at a number of points along the career pathway in England has hampered progression.

16. These ‘bottlenecks’ are present and growing at: entry to foundation training as applicant numbers have increased, resulting in the need for placeholder posts; between foundation and core programmes, resulting in significant numbers of doctors seeking LED posts at ‘FY3’ level; and at entry to higher specialty training level. GMC progression reports show that up to 78% of foundation year 2 doctors did not move directly into training programmes in 2023.

Figure 17: Most important barriers to a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Figure 18: Least important barriers to a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

17. From a workforce perspective, many stakeholders reported a mismatch between the number and distribution of training posts and the actual needs of both services and patients. This was a view very frequently expressed by Royal Colleges and clinical services in the call for evidence and the focus groups.

- 76.7% disagreed that current recruitment meets population health needs

- 82.2% disagreed that current distribution of training meets workforce needs

18. We frequently heard that there is a clear tension between the aspirations of resident doctors to have greater control over the specialty they train in and the place where they work and the need to provide a medical workforce mapped to population need. This is demonstrated by geographical location being a leading factor in supporting a satisfactory career in the call for evidence (Figure 19). Submissions from the medical Royal Colleges and faculties, devolved nations and clinical service focus groups highlighted the need to consider approaches to rebalance the historical distribution of training posts to manage the changing population distribution and need.

Figure 19: Most important factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

Figure 20: Least important factors for a rewarding postgraduate medical training pathway: Weighted score (%)

19. Although doctors may choose LED roles because they enable greater flexibility or avoid repeated relocations, the literature review illustrated that the limited numbers of training posts have led to the significant increase in LEDs, working outside formal training programmes. This was supported by the LED focus group and call for evidence free text comments. Employers have been clear that some of the need to expand LED posts is to ensure that rotas are filled and compliance with the working time directive requirements.

Rotation instability

20. Currently, UK resident doctors typically rotate through different hospitals (often in different cities or counties) every 6–12 months. While this provides breadth of experience, it can be highly disruptive to personal life, contributing to stress and even deterring some from entering training. This is exacerbated by distances between placement providers, notably in regions with greater rurality.

21. This has been identified both by NHS England and within the non-pay agreement between the British Medical Association (BMA) and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), triggering a review of the rotation model. Resident doctors frequently described the instability caused by frequent geographical rotations, often with short notice and limited continuity, and the emotional, financial and logistical burden of moving frequently between placements. They highlighted a lack of agency in choosing rotation sites.

22. The frequency of rotation also impacts on the ability to develop a relationship between trainee and trainer and results in ‘lost’ training opportunity while the resident doctor becomes accustomed to a new team or working environment.

23. Comments highlighted that resident doctors cannot forward plan if rotations are not confirmed with appropriate notice and the rotation plan for a resident doctor’s entire programme is not available. Faculty responses highlighted that certainty of programme placements is difficult to deliver alongside facilitating flexible training and managing requests for statutory leave or experiences out of programme (OOP).

24. In responses to the call for evidence, the current rotational structure was the second most cited barrier to a rewarding and satisfying postgraduate medical training pathway (13% of all votes; Figure 17). Foundation doctors and LEDs described being relocated multiple times within a few years, often at short notice, disrupting personal and professional stability. Doctors with disabilities or caring responsibilities found current models particularly challenging.

“I’ve moved house 3 times in 2 years, no wonder people feel disconnected and unsupported.” (Foundation doctor focus group)

“Being told on short notice that I have to relocate again makes it hard to plan my life.” (LED, CfE, free text response)

“We want doctors who stay, who understand our community – not strangers who rotate through.” (Patient group member, coastal community)

25. Service providers and integrated care board leaders identified rotational training as a barrier to building strong relationships with resident doctors; they can be perceived to be a ‘temporary’ workforce. This will reduce a resident doctor’s sense of belonging to the team in which they are placed and worsen their sense of ‘dislocation’ from place. Some providers, notably those with smaller secondary care units, identified that they rarely saw more senior resident doctors and therefore struggled to attract them as future consultants, reducing their ability to recruit a substantive senior workforce.

26. While the need for flexibility was clearly stated, both resident doctors and their faculty recognised that providing detail of every placement for a programme was challenging when flexible training, statutory leave and periods of OOP were factored in.

Personal agency, flexibility and bespoke training

27. Resident doctors called for greater personal agency – more control over location, specialty route and pace of training. “The system isn’t built to flex – you have to bend yourself to fit it,” observed one doctor in academic postgraduate training. The current model is viewed as too rigid, failing to reflect the diversity of doctors’ lives and aspirations.

28. Flexibility has 2 forms: the ability to create a more varied path through the early years of training, largely around the job mix that makes up a training path; and flexible ways of working within a job, especially (but not exclusively) for those with caring responsibilities. Respondents were in favour of both forms, but they should be seen as distinct.

29. Flexibility was a common theme in the call for evidence: 54.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed that training processes are flexible enough.

“Flexibility isn’t just nice to have, it’s how we retain people in the system.” (SAS doctor focus group)

“We want to be treated like professionals, not just numbers moved around to fill rota gaps.” (IMG focus group)

“After having children, I moved to less than full-time training but this meant I was much less likely to be given my preferred rotations or training locations. I had to take a break entirely for a while and the return felt like starting from scratch.” (Resident doctor, CfE, free text response)

30. Respondents called for more flexible progression models, better recognition of prior learning and options to tailor their career pathway. Specific requests included being able to switch specialties while recognising transferable capabilities, dual accreditation options and training pathways accommodating caring responsibilities or portfolio careers.

31. The current model of less than full-time (LTFT) training is welcomed and increasingly taken up by those in training, as described in section 1.3. However, providers voiced concerns that this was undermining their ability to fill out of hours rotas and ensure coverage of posts and equitable access to training opportunities.

32. In addition, we heard a call for flexibility around career diversification, including capabilities and skills that, while sitting outside core clinical requirements, are still considered important for the development of the NHS and improvements in patient care. These could include technology development and clinical entrepreneurship.

33. One theme we heard from foundation doctors and medical students related to the current way foundation posts are allocated – the preference informed allocation. Despite this being based on applicants’ individual preferences in line with past students’ wishes, this is perceived to remove a doctor’s ability to influence their career pathway through demonstrating excellence.

Disabled and neurodivergent doctors

34. The round tables focused on the needs of disabled and neurodivergent doctors identified that ensuring reasonable adjustments (those that do not have a negative impact on patient care) can be challenging and stressful for doctors and changes in training location or employer during rotations makes this harder.

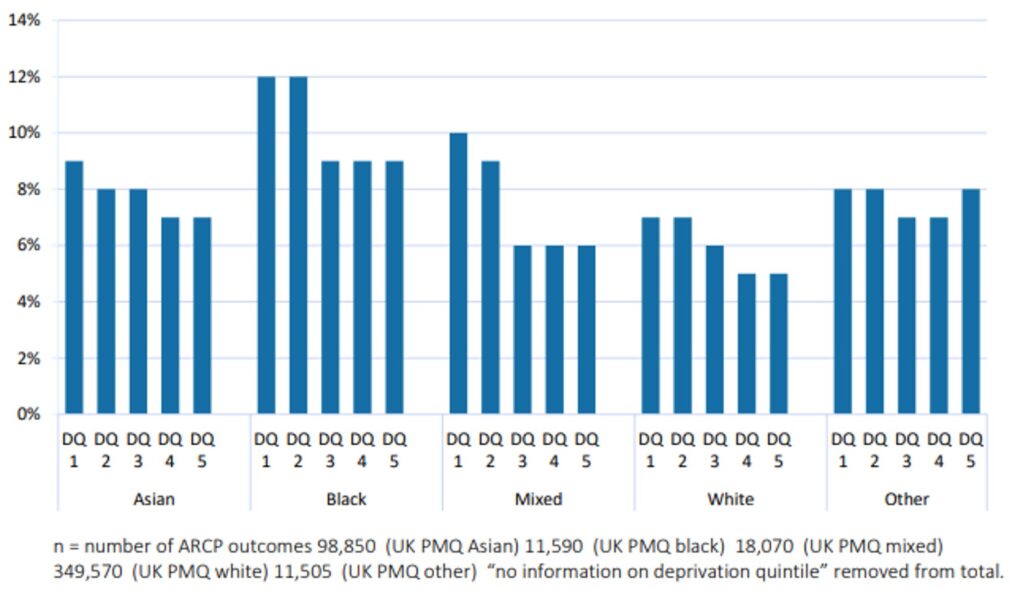

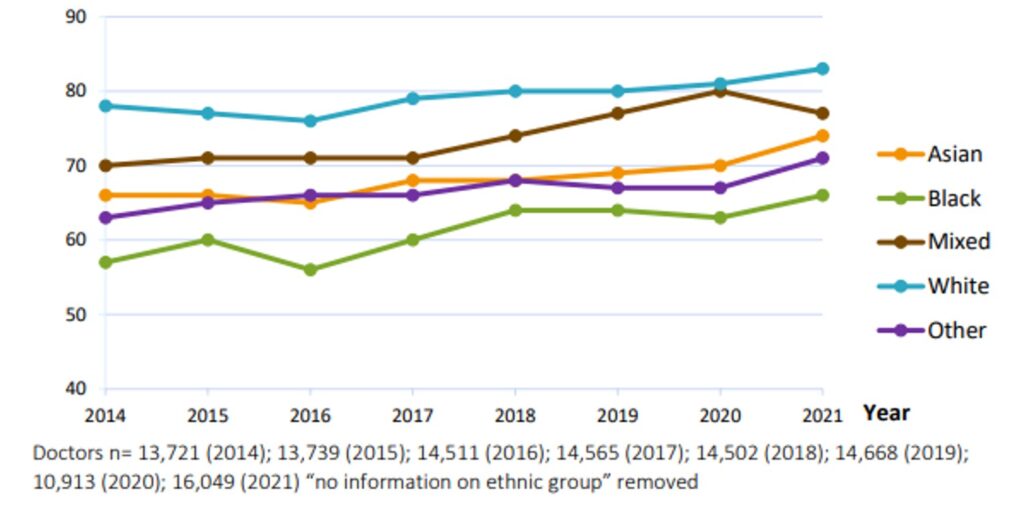

35. Other factors cited as inhibiting their progression were cultural and systemic barriers, bias and misunderstanding of the impact of neurodivergence or disability on the doctor. Discrimination was highlighted during round tables and is well described in the literature, with attainment gaps at recruitment and both assessments and examinations.

Workplace cultures and behaviours

36. A critical aspect of training culture is the persistence of bullying, harassment and discrimination in some environments. The GMC 2025 national training survey highlights ongoing concerns around discrimination and incivility, with notable disparities across gender and ethnicity. For example, 17% of female trainees reported being ignored or excluded compared with 13% of male trainees, while 34% of UK graduates from ethnic minority backgrounds experienced micro-aggressions compared with 25% of their white colleagues. The survey also found that trainees from ethnic minority backgrounds were less confident about reporting discriminatory behaviours without fear of adverse consequences, indicating that barriers to speaking up remain for some groups.

37. Several forums and programmes have tried to improve this, such as The Working Party on Sexual Misconduct in Surgery (WPSMS) and the Safe Learning Environment and Sexual Safety Charter developed by NHS England.

38. Surgical resident doctors in particular have raised concerns about an “old boys’ club” culture; the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh expressed grave concern at the 2023 findings of 1 in 10 surgical resident doctors encountering sexual harassment and many more witnessing or experiencing bullying. Such a culture is clearly detrimental to training and mental wellbeing.

39. In April 2025, Turning the tide (2025) sets out eight priority actions. The Royal College of Surgeons of England commits to a zero tolerance approach and working closely with WPSMS to drive reform.

40. Tackling this requires strong institutional action: zero-tolerance policies, easy and safe reporting mechanisms and positive role modelling by all staff. There is also a need for greater diversity in leadership and faculty to drive an inclusive culture.

Craft specialties

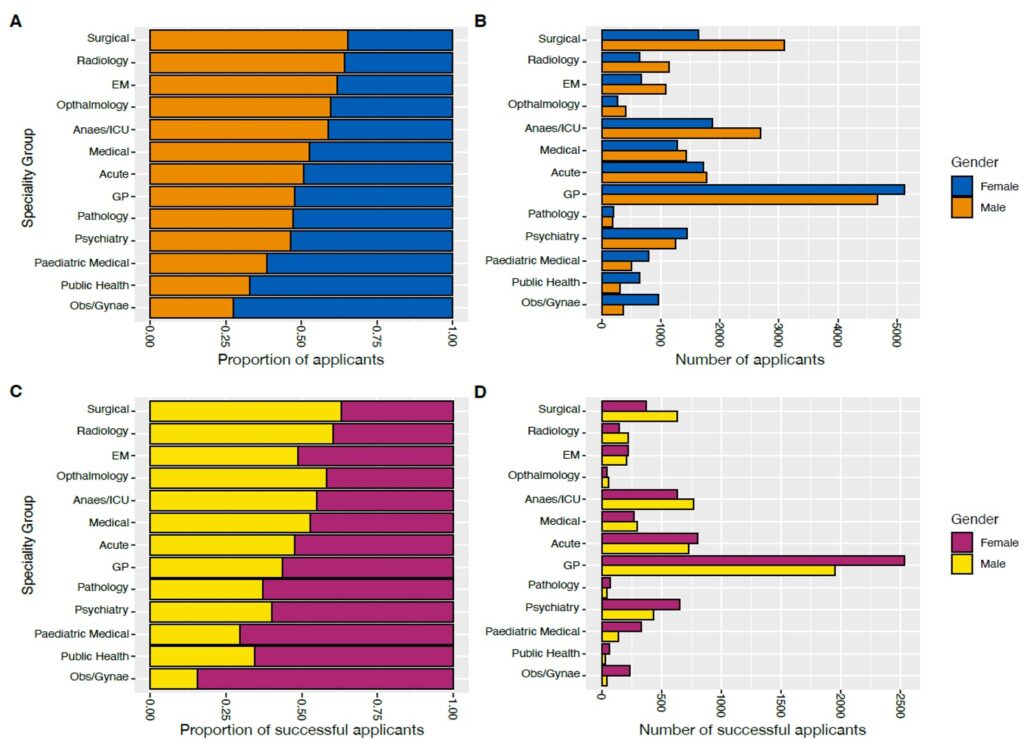

41. Craft specialties are those for which practical skills are a core part of the role. They include the surgical specialties and others where the practical component is significant (anaesthetics, obstetrics and gynaecology, cardiology, gastroenterology, ophthalmology and interventional radiology) and bring their own challenges in access to training. Focus groups reported challenges in ophthalmology, for example, due to the shift of NHS work to the independent sector, in particular the simpler operations that are ideal for early training. They considered it should be a condition of the independent sector taking on NHS work that proper provision is made for training.

42. Competition for training opportunities was highlighted, both among groups of resident doctors and between them and other healthcare trainees. Additionally, concerns were raised about balancing clinical service demands with the need to provide sufficient training in operations and procedures.

43. A lack of infrastructure and investment in training, notably for training in new technologies, were also highlighted, with respondents and service providers feeling that training in some fields does not produce ‘job-ready’ craft doctors.

44. Whether the duration of training in these specialties and the content of curricula currently meet the patient health needs of a local population were also questioned. The focus was the balance between a curriculum training to the needs of the local population and the desire for significant specialisation: what aspects of specialty training should be common to all rather than part of post-appointment development as a substantive consultant.

45. Frequency of ‘out of hours’ duties on acute services rotas coupled with the working hours limits was frequently cited as a reason for the loss of access to theatre and diagnostic procedure lists and, therefore, loss of training opportunities.

Clinical academic medicine

46. We recognise that the report Clinical researchers: reversing the decline highlighted concerns about the provision of training for this section of the medical workforce. Some medical disciplines have relatively good provision of academic placements, but in others the ratio of clinical academic training posts to other training posts is very low.

47. There is growing evidence that in some specialties the number of doctors embarking on an academic programme who ultimately take up a senior clinical academic position is small, and a suggestion that academic clinical fellow posts are seen as an alternative route to clinical training, notably where the number of clinical training posts is small.

48. Inputs into the call for evidence and at the clinical academic round table identified themes around the practical complexity of completing integrated academic training; the challenges of achieving both clinical and academic capabilities, notably if dual accrediting (for example, in a medical specialty and general internal medicine); and the funding gaps for doctorate level study.

49. Clinical service demands were noted to reduce or displace clinical academic time. However, respondents recognised the benefits of an integrated approach that is unique to England, funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), and were keen not to lose this in any change.