Classification: Official

Publication reference: PRN01288

To

- Integrated care board (ICB) and trust

- chief executives

- medical directors

- chief nurses

- directors of finance

- chief people officers

- chief operating officers

cc:

- ICB and trust chairs

- Regional:

- directors

- directors of commissioning

- directors of system transformation

Dear colleague,

Urgent and emergency care recovery plan year 2: building on learning from 2023/24

Thank you to you and your teams for the progress made over 2023/24 in delivering the actions set out in the Delivery plan for recovering urgent and emergency care (UECRP). Despite significant headwinds in the form of unprecedented industrial action and higher than anticipated demand, the hard work of NHS and social care colleagues across the country has seen marked year-on-year improvement in the headline ambitions set out in the plan.

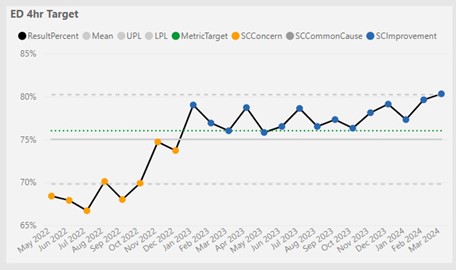

2023/24 was the first non-pandemic year since 2009/10 that A&E 4-hour performance was better than the previous year, with over 2.5 million more people completing their A&E treatment within 4 hours compared to 2022/23. Response times for category 2 ambulance calls also improved; over the year, the average response time was 14 minutes faster compared to the previous year.

Other benefits for patients included:

- tens of thousands more people received the care they needed to return home quickly and safely thanks to the expansion of same day emergency care (SDEC) services

- on average, around 500 fewer patients a day had to spend the night in hospital because of a discharge delay, and 13% more patients received a short-term package of health or social care to help them continue their recovery after discharge

- urgent community response teams provided 720,000 people with an alternative to going to hospital between April and January

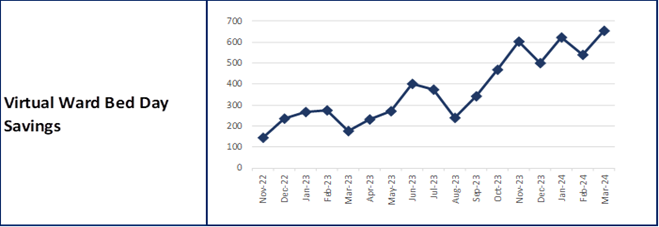

- virtual wards have supported more than 240,000 people to get the hospital-level care and monitoring they needed in the comfort of their own home

Maintaining progress

The UECRP is a 2-year plan. The level of ambition for 2024/25 was recently set out in the NHS priorities and operational planning guidance:

- improve A&E performance with 78% of patients being admitted, transferred or discharged within 4 hours by March 2025

- improve category 2 ambulance response times relative to 2023/24, to an average of 30 minutes across 2024/25

This operational planning guidance asked systems to focus on 3 areas to deliver these ambitions:

- maintaining the capacity expansion delivered through 2023/24

- increasing the productivity of acute and non-acute services across bedded and non-bedded capacity, improving flow and length of stay, and clinical outcomes

- continuing to develop services that shift activity from acute hospital settings to settings outside an acute hospital for patients with unplanned urgent needs, supporting proactive care, admissions avoidance and hospital discharge

This letter and its supporting annexes aim to help systems and providers as they plan and prioritise over the coming weeks, in order to make progress over the summer and improve resilience ahead of winter, by bringing together in one place what we know works in support of the key requirements set out in planning guidance.

Evidence-based actions to support delivery

Over the last year we have learned a significant amount from systems and providers – both through engagement as well as the early findings of formal evaluation – about how best to deliver for patients and for staff in the context of a challenging financial environment.

Annex 1 summarises the actions that work, and maps these against the requirements set out in planning guidance. Annex 2 provides further detailed information on those evidence-based delivery actions that we know will make a difference, as well as providing the supporting evidence and case studies.

This document is focused on acute and community services, and the needs of people with mental health issues in those services. It does not specifically address mental health settings; however, many of the principles and delivery actions will apply, such as working jointly with local government and social care partners to make effective use of the Better Care Fund for mental health pathways.

Working with local government, adult social care and the voluntary sector

The effectiveness of UEC services relies on the NHS, local authorities, providers of health and social care services, and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCS)E partners working together across the UEC pathway. Throughout the last year, there have been excellent examples of partnership working to prevent avoidable hospital admissions, speed up discharge and improve outcomes for patients.

During 2024/25, continued partnership working – including with patients, families and carers – will build on and strengthen this joint approach. Annex 3 sets out the shared objectives, and this letter is being sent in conjunction with a letter from the Department of Health and Social Care to local authorities to ensure alignment across systems. This will help sustain a joined-up, collaborative approach to improving UEC services and outcomes for patients.

Delivery support

NHS England has also heard from systems and local teams what support offers have been helpful, and the support offer in 2024/25 has been refined as a result.

The UECRP set out an approach to UEC tiering support. Over the last year, this approach has supported improvements for challenged systems and providers, and helped to reduce unwarranted variation. It has been aligned with support for local government through the joint NHS England and Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Discharge Support and Oversight Group, which works with challenged systems to support improvements in discharge across all local partners. Annex 4 provides an analysis of the progress made by systems in Tiers 1 and 2, as well as additional learning on success factors.

For 2024/25, NHS England will continue to apply the same tiering approach, providing support to systems that are below target and/or are outliers on key metrics. The support will take account of learning from our review of tiering work to date, in particular by better aligning with NHS England’s other tiered offers to systems, the Recovery Support Programme team and cross-government offers such as the Better Care Fund (BCF) support programme, and by ensuring clear agreement of priorities for improvement across national, regional and local teams.

NHS England also offered a universal support offer to drive improvement and innovation across 10 high impact areas, which included working with the BCF support programme for those areas that require a joined-up approach across health and social care, such as capacity planning for intermediate care and effective implementation of care transfer hubs.

Feedback from participating systems highlighted benefits to working in this way, although other systems reported finding it difficult to engage with. This feedback has been built into our approach to supporting systems in 2024/25, and will also underpin future support packages for local systems to deliver improvement in clinical outcomes and productivity. There will be a continuing focus upon the 10 high impact areas for 2024/25 within the wider holistic approach; these have been incorporated into Annex 1 with additional detail and evidence-based actions to support further improvements within Annex 2.

Measuring progress

In addition to the 2 headline ambitions, the planning guidance sets out that systems and regions should focus on reducing the number of over 12-hour waits in emergency departments (EDs), including for mental health patients awaiting admission to a mental health bed.

NHS England will also be regularly considering the following supporting metrics in assessing performance and where additional support may be required:

- reducing ambulance handover delays

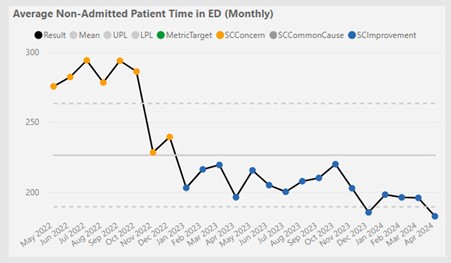

- reducing admitted and non-admitted time in EDs, with an intention of reducing long waits, particularly for mental health patients

- maintaining average G&A core capacity across the year at the level achieved in the last quarter of 2023/24, equivalent to at least 99,500 beds nationally, allowing for seasonality

- improving length of stay for all admitted patients (specifically emergency admissions with a length of stay of 1+ day)

- reducing average delays post discharge ready date (combining the two published metrics (a) the percentage of patients discharged on their discharge-ready date and (b) the average delays for patients not discharged on their DRD)

- improving length of stay in NHS commissioned community beds

Accountability

Building on the experience from 2023/24, the NHS will continue to ensure the key elements of implementation and delivery support are in place, starting with clear accountability for delivery through the NHS Oversight Framework. The new operating framework will also provide clarity on outcomes and priorities, while providing local flexibility on how to deliver.

The NHS Oversight Framework sets out the key outcomes expected of integrated care boards (ICBs), and will be supported by regional UEC delivery boards as well as a national programme board that will review any issues occurring across regions.

On a day-to-day basis, a new OPEL framework has supported aligned accountability on operational risk management, managed at integrated care system (ICS) level through our system co-ordination centres. Over winter 2023, this new framework has supported the 24/7 National Co-ordination Centre, and enabled NHS England to provide targeted support when there has been pressure. NHS organisations continue to work routinely with local authorities to manage operational risks that require co-ordinated health and social care action.

The OPEL frameworks for mental health and community services are now being developed. The frameworks will use the same principles as the acute care OPEL 2023/24 (that is, digital, clinically relevant and consistent). NHS 111 OPEL and revised acute care OPEL will be part of a weighted system aggregated score, to increase both the pace and rigour of our response to patient safety within the entirety of the UEC pathway.

Transparency

Over the last 12 months the NHS has made strong progress on improving the availability of data to support service improvement and transparency for patients and the public. Key developments included:

- publication of 12-hour waits

- development and publication of a new dataset derived from the discharge ready date (DRD)

For 2024/25, a key priority will be to continue to improve the collection and quality of DRD data and data on reasons for discharge delays, and to improve data collection on community services. This includes ensuring that all relevant trusts are reporting high-quality data on DRD, to enable comparison at trust, local authority and ICS levels. This will help drive effective shared action across the NHS and social care to improve timely discharge. By July 2024, all community providers of NHS commissioned services should be reporting into the Community Services Data Set. These metrics will support better local and national assessment of flow and capacity.

Capital and incentives

A total of £250 million of operational capital was provided in 2023/24 to support estate and technology improvement relevant to UEC. A further £150 million of capital was also allocated in 2024/25, as part of a scheme to incentivise higher performance in 2023/24.

This year, £150 million of operational capital is being distributed for improvements that will support front door services and flow through EDs, to support improvements in ED performance. NHS England regional teams are working with systems to progress business cases; further details will be available once these have been agreed.

In addition, there will be up to £150 million of capital allocated within NHS operational capital budgets in 2025/26, to incentivise both highest performance and greatest improvement in performance since 2023/24. An outline of the scheme is set out below:

- improved 4-hour performance (measurement at year end, with a further element to incentivise improvement throughout the year)

- improved Category 2 performance (incentivised throughout the year)

- reduction in 12-hour delays in an ED (incentivised throughout the year)

Schemes will not be mutually exclusive. Capital will be allocated to the ICB for the category 2 ambulance response performance and improvements, and to individual trusts and their nominated partners (which may include community and mental health trusts) for the A&E schemes.

Thank you again for the incredible work that you and colleagues have done together to improve the timeliness, quality and safety of care for patients requiring urgent and emergency treatment over the first year of the UECRP. We hope this further information is helpful in the planning you are doing now for the second year, and we look forward to continuing to work with you to support further improvements over the course of 2024/25.

Yours sincerely,

Sarah-Jane Marsh CBE, National Director of Urgent and Emergency Care and Deputy Chief Operating Officer, NHS England.

Dr Julian Redhead, National Clinical Director for Integrated Urgent and Emergency Care, NHS England.

Annex 1: Summary of supporting actions

|

Operational planning guidance requirement |

Evidence-based actions to support delivery |

|

1. Maintain the capacity expansion delivered through 2023/424 | |

|

1A. Maintain acute G&A beds at the level funded and agreed through operating plans in 2023/24 |

|

|

1B. Maintain ambulance capacity and support the development of services that reduce ambulance conveyances to acute hospitals |

|

|

1C. Focus on reduction in ambulance handover delays to support system flow |

|

|

1D. Expand bedded and non-bedded intermediate care capacity, to support improvements in hospital discharge and enable community step-up care |

|

|

1E. Improve access to virtual wards through improvements in utilisation, access from home pathways, and a focus on frailty, acute respiratory infection, heart failure, and children and young people |

|

|

2. Increase the productivity of acute and non-acute services across bedded and non-bedded capacity, improving flow and length of stay, and clinical outcomes | |

|

2A. Focus on reductions in admitted and non-admitted time in ED |

|

|

2B. Focus on reductions in the number of patients still in hospital beyond their discharge ready date (DRD) |

|

|

2C. Focus on reductions in length of stay in community beds |

|

|

2D. Improve consistency and accuracy of data reporting |

|

|

3. Continue to develop services that shift activity from acute hospital settings to settings outside an acute hospital for patients with unplanned urgent needs, supporting proactive care, admissions avoidance and hospital discharge | |

|

3A. Increase referrals to and the capacity of urgent community response (UCR) services |

|

|

3B. Ensure all Type 1 providers have an SDEC service in place for at least 12 hours a day, 7 days a week |

|

|

3C. Ensure all Type 1 providers have an acute frailty service in place for at least 10 hours a day, 7 days a week |

|

|

3D. Provide integrated care co-ordination services |

|

Annex 2: Further detail on supporting actions

Learning from the first year of the Urgent and emergency care recovery plan

The approach to developing this document has been 2-fold. Learning has been drawn from regular conversations with systems across health and social care, which has highlighted the interventions and approaches that have been easier to implement, and what would need to be true to replicate this elsewhere.

Systems that are further ahead with implementation have documented their approach in case studies; examples are given in these annexes.

We have also begun to see emerging learning from the evaluation approach that was set out in the UECRP. This includes some insights from Sheffield University’s literature review, alongside emerging findings from qualitative evaluation by the REVAL team at Manchester University. The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), a partner to NHS England in evaluating the Urgent and emergency care recovery plan (UECRP), along with the case study authors, will make these findings available in due course.

Overall, NHS England has heard and seen that the broad approach set out in the UECRP is the right collection of activities to enable the NHS, working with local authorities, social care providers and VCSE partners, to deliver the ambitions of the plan.

NHS England has also heard from systems and local health and social care teams implementing the UECRP on the ground that they would value the opportunity to continue with their delivery and embedding of changes into Year 2. Teams have also asked for evidence-based, structured products to highlight the key components of the interventions, and to support prioritisation of their delivery.

We have been told – and seen in the data – that some of these interventions have been easier to implement routinely across systems than others. Both standardising the approach to delivering services across health and social care to improve support for frailty, and standardising the approach to inpatient flow and length of stay, have been raised as consistent challenges. Further work is underway with partners and stakeholders across the country to establish and document a more succinct approach to improving these pathways.

To help and support delivery into Year 2 of this plan, NHS England has responded to this learning in 2 ways. The approaches that work have been collated and refined into a set of evidence-based actions for health and social care systems to support delivery of and progress towards the headline ambitions, alongside links to further guidance, evidence and examples of best practice. These actions are set out below, grouped under the 3 UEC priority areas for this year: maintaining UEC capacity, improving the productivity of that capacity, and continuing to shift care out of acute hospitals.

In implementing these actions, working with social care and VCSE partners, systems should include, wherever appropriate, children and young people, patients with mental health needs and dementia, people with learning disabilities, autistic people and those experiencing homelessness within their plans.

In these newer pathways, or those that have been more challenging to implement, evidence of what works is being codified to support wider national learning. Some of this detail is already available, with some further detail to follow shortly.

Interventions for frameworks that are already available

- Care transfer hubs

- SAMEDAY framework for same day emergency care

- Combined adult and paediatric acute respiratory infection hubs

- Discharge ready date guidance (includes DRD definitions)

- Discharge guidance (including homelessness checklist)

Interventions for frameworks that will be published shortly

- Virtual wards

- Single point of access/integrated care co-ordination centres

Pathways for which work is ongoing with local and regional teams over the coming weeks

- Standardisation of services to support older people with frailty

- Standardisation of inpatient flow and length of stay

Priority 1: Maintaining and increasing the capacity expansion delivered through 2023/24

During 2024/25, systems should continue to ensure that UEC capacity is maintained or, where appropriate, expanded. Alongside the increase in physical capacity, and in line with the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, systems should continue to take action to support the UEC workforce, including enabling staff to work more flexibly.

Learning during 2023/24

During 2023/24, the NHS delivered significant capacity expansion, supported by over £1 billion of new revenue and £250 million of new capital investment. The NHS and local authorities also worked together to agree how to deploy the £600 million Discharge Fund, alongside the wider BCF, to improve capacity for supported discharges and reduce discharge delays, delivering a 13% increase in supported discharges in 2023/24 compared to 2022/23 and – despite a 6% increase in emergency admissions over this period – a 4% reduction in the average daily number of acute hospital patients with delayed discharges.

This capacity expansion has had an impact, as evidenced by the improved overall performance in the UECRP’s 2 headline ambitions against the previous year. Modelling underpinning the planning guidance highlights the relationship between capacity increases and ED performance, largely driven by bed occupancy. Further modelling highlights the relationship between handover performance and handover delays, and by extension category 2 performance.

Evaluation from newer interventions, such as virtual wards, has also begun to build a picture of where and how improvement can have most effect. For example, there is strong evidence that virtual wards are associated with reducing avoidable attendances and admissions to hospital, as well as supporting early discharge and reducing length of stay in acute beds.

- There is growing positive evidence of impact from site evaluations:

- East Kent’s 50-bed step-up frailty virtual ward has seen a reduction in non-elective admissions for older frail cohorts (75+). A South East region-wide evaluation is due to be published demonstrating similar results across the region

- South and West Hertfordshire Health and Care Partnership experienced a reduction in hospital bed days from the implementation of a COPD ward hospital at home pathway with an observed reduction in both inpatient length of stay and the number of repeated hospital admissions

- evaluation of the Mid and South Essex frailty virtual ward found that readmission rates to an acute bed within 30 days of discharge were 26.5% lower than the 30-day readmission rate seen nationally for acute frailty wards

- Virtual wards also deliver cost savings, as demonstrated in an economic analysis by NICE, which found that in aggregate the services have provided a significant net financial benefit due to avoided hospital activity. Across multiple evaluations, there is also consistent evidence of very positive patient experience of virtual ward services.

Learning from joint ICB/local authority capacity and demand planning for intermediate care through the BCF has reinforced the importance of actively reviewing projected need for different types of intermediate care, including both step-up and step-down care. It has also reinforced the importance of working with community and social care providers to plan services and associated workforce requirements so that they better match projected needs, including a focus on a ‘Home First’ approach to reablement and recovery. Local areas have also reinforced the importance of understanding the relationship between average length of stay in different types of intermediate care and the capacity available to meet projected demand.

This learning has informed the planning guidance requirements and the supporting delivery actions set out below for 2024/25. Further evidence is set out in case studies and links throughout this section.

Based on evidence from last year, key supporting actions for 2024/25 include:

1A. Maintain acute core G&A beds as a minimum at the level funded and agreed through operating plans in 2023/24

- Core G&A bed numbers should be maintained through monitoring and maintaining the average of 99,500 beds over 2024/25, adjusted for seasonal trends.

1B. Maintain ambulance capacity and support the development of services that reduce ambulance conveyances to acute hospitals where appropriate

- Ambulance trusts maintaining the increase in deployed staff hours established in 2023/24, to maintain the peak increase in capacity agreed in operating plans.

- Systems increasing clinical assessment in NHS 111 and control centres compared to 2023/24, in line with national implementation principles for category 2 segmentation. This will ensure that patients who do not need a face-to-face response are transferred to the most appropriate service and supports effective prioritisation for ambulances. This may include increasing access to paediatric expertise through a NHS 111 Paediatric Clinical Assessment Service, where supported by evaluation and business case development.

- Systems maximising opportunities to establish ‘call before you convey’ best practice models to increase direct referral to alternative services, where clinically appropriate. These best practice models include early access to a named senior clinical decision-maker so that patients with the most urgent need are seen sooner.

- Ambulance trusts deploying the paramedic workforce, including ambulance support staff, in the most effective way to meet ambulance capacity requirements in line with local need.

- Ambulance trusts embedding culture improvement alongside the delivery of operational targets, by implementing the recommendations set out in the Culture review of ambulance trusts.

Case study: Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust – Virtual Eye Pathway

‘The Virtual Eye Pathway’ is an integrated virtual consultation pathway between NHS 111 and the Moorfields Eye Hospital within North Central London (NCL) and North East London (NEL) ICBs, which aims to reduce the number of calls related to urgent eye conditions that result in avoidable ED attendances.

With the new pathway, NCL and NEL ICB callers to NHS 111 with urgent eye conditions will be briefly assessed and then transferred to a virtual waiting room, after which they shortly receive a specialist ED virtual ophthalmology assessment provided by a Moorfields clinician. The clinician then streams patients to the most appropriate service (often an opticians, a minor eye condition service or Moorfields itself) or provides advice and guidance to enable self-treatment.

Since the Virtual Eye Pathway launched in March 2023, 30% of patient callers who would previously have resulted in a Type 1 ED attendance have been avoided, with patients directed elsewhere. Those referrals that do result in an A&E attendance have the benefit of being validated by a specialist clinician in advance of attendance. Wider benefits have included reduced patient wait times within NHS 111, especially where specialist ETC ophthalmology assessment is required, and reduced Type 1 ED referrals overall. In addition, access to this service has been expanded via the 111 Online channel so that users of NHS 111 Online can obtain urgent eye care assessment directly through this online channel. The virtual eye service is also linked to the London 111 natural language pathway development, so that users who declare urgent eye problems will streamline directly to this service via NHS App/111 Online.

1C. Reduce ambulance handover delays to support system flow

- Handover delays still present a significant challenge to increasing ambulance service capacity, particularly in certain areas. Due to the impact on patient care, reducing these delays will be a key focus and action for systems to deliver in 2024/25. This will remain a metric to better assess flow across UEC pathways and support improved patient outcomes.

Case study: Barts Health NHS Trust – REACH service

The Remote Emergency Access Coordination Hub (REACH) is a UEC collaborative in North East London set up in October 2020. Developed and hosted by Barts Health NHS Trust initially as a response to COVID-19, it aims to co-ordinate and deliver the most appropriate secondary emergency care for patients.

Ambulance service paramedics, urgent community response (UCR) and primary care clinicians on scene with a patient are able to call the REACH service to receive emergency medicine consultant-led clinical advice regarding best options for the patient, including support for appropriate non-conveyance. The REACH service provides collaborative decision-making with the caller, facilitating remote treatment and discharge or direction to alternative care pathways where appropriate, which improves patient experience and optimises utilisation of both community and in-hospital resources such as UCR, SDEC and virtual wards.

In 2023, REACH took 11,600 calls from clinicians in the community (93% of those from London Ambulance Service) and 4,200 referrals from NHS 111, with 10,300 patients managed without in-person ED attendance. This equates to a 29% ambulance conveyance rate, a statistically significant reduction in ambulance arrivals in all boroughs served.

With strongly positive patient and staff feedback, a system-wide saving of over £1.5 million a year and an estimated saving of 156 tonnes of CO2 emissions, REACH has proven to be a safe and effective clinical co-ordination service.

1D. Expand bedded and non-bedded intermediate care capacity, to support improvements in hospital discharge and enable community step-up care

- ICBs and local authorities will need to review their BCF demand and capacity plans to ensure that commissioned capacity meets forecast need, to support both discharge and step-up care. Systems should ensure accurate estimates of demand from discharges and from community referrals are used to commission the appropriate volumes and types of intermediate care capacity, supported by the increase in the Discharge Fund (from £600 million in 2023/24 to £1 billion in 2024/25). Plans will include making clear assumptions for average length of stay, and will actively consider the most appropriate balance between Pathway 0, Pathway 1, Pathway 2 and Pathway 3 discharges. They will take account of variations in demand over the course of the year and building potential ability to flex into forecasting models. Further support setting out the joint requirements for the NHS and local government to deliver the objectives of the BCF is included within the Better Care Fund 2024/25 addendum and associated demand and capacity planning templates. Plans will be assured through the BCF assurance process to ensure they are robust and deliverable.

- When conducting demand and capacity planning, systems should work with community and social care providers to ensure there is sufficient workforce capacity with the appropriate skill mix to deliver the required capacity. This ‘right sizing’ of capacity has been successfully achieved in some systems by making more effective use of both registered and unregistered workforce, and by using other community roles to support rehabilitation and reablement both in people’s homes and, where appropriate, in community beds.

- The Intermediate care framework for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery following hospital discharge, and the Community rehabilitation and reablement model, set out the approach to service delivery.

Case study: Oxfordshire Integrated Care Board – out of hospital care for people experiencing homelessness

Through start-up funding from the DHSC Out of Hospital Care Programme, Oxfordshire has implemented an excellent hospital in-reach and step-down service, which is helping transform patient’s lives, prevent a return to rough sleeping, and dramatically reduce discharge delays and avoidable readmissions from acute and mental health hospitals.

Under the leadership of a dedicated programme manager, and with support and funding from the ICB, BCF and health and care partners, the programme has appointed experienced housing officers co-located in acute and mental health hospitals. They bring extensive legal knowledge related to housing applications in addition to working knowledge of local housing and homelessness services to support ward staff in planning individual’s transition from the hospital.

Oxford has opened 4 step-down houses with 27 beds in the community, which include access to rehabilitation, reablement and recovery services, a social worker, occupational therapist, clinical psychologist and community based mental health workers. This service enables individuals to recover their mental health in the community and develop independent living skills, and facilitates services coming together collaboratively to support the individual.

The service has supported over 250 planned discharges from hospital (50% from mental health wards). Where a discharge has included a stay in a step-down house, there has been a 24% reduction in emergency hospital admissions and a 56% reduction in presentations to EDs. Over the 12-month evaluation period, mental health bed days were reduced by 89% – saving the NHS £657,000. Patients are no longer ‘stranded’ in hospital and very rarely return to rough sleeping.

1E. Improve access to virtual wards through improvements in utilisation, access from home pathways, and a focus on frailty, acute respiratory infection, heart failure and children and young people

- Systems maintaining capacity of virtual ward/hospital at home (HaH) beds, and expanding access by ensuring utilisation is consistently above 80%. Guided by feedback from systems, a new virtual wards operational framework will be produced in spring/summer 2024 to help tackle variation, achieve further standardisation and ensure the benefits of virtual wards/HaH can be realised at scale.

- Systems (including local authorities) and providers working together locally to increase the proportion of virtual ward beds accessed from home (‘step up’ virtual wards), including directing patients from EDs and SDEC following initial assessment where appropriate. In doing so, it would be helpful to pay particular attention to improving the coverage of paediatric virtual ward services and capacity.

- A new patient-level dataset for virtual wards (the Virtual Ward Minimum Data Set [VWMDS]) is being developed. When launched, providers will be expected to submit to the VWMDS, supporting local systems to have enhanced operational oversight of virtual wards as well as to enable national benchmarking. Further information on rollout will be published in due course.

Case study: Cambridge University Hospitals – virtual wards

In November 2022, Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) developed a virtual ward designed to deliver hospital-level care for patients in their own homes, using remote monitoring technology. The focus was on delivering 45 occupied virtual ward beds by September 2023 that delivered step-down discharge care, to free up capacity in the hospital.

A significant amount of pathway development work was undertaken to make the service available to every specialty in the hospital. Key to this was use of a remote digital monitoring technology, which allowed the team to monitor the vitals of all their patients continuously and spot when a patient was deteriorating. This helped build confidence with clinicians to refer their patients, given assurance as to the level of care and monitoring they would receive.

In just over 1 year of being operational, the CUH virtual ward has onboarded over 1,500 patients from 23 different specialties, including frailty, oncology, surgery, orthopaedics, cardiology and respiratory. It has exceeded its occupancy figure by almost double and the patient experience survey has a 97% satisfaction score. The wider benefits are considerable, with significant length of stay and associated bed day savings. CUH is now developing its model further to start delivering step-up and admissions avoidance care, and eventually include access pathways from primary care and care homes too.

Priority 2: Increasing the productivity of acute and non-acute services across bedded and non-bedded capacity, improving flow and length of stay, and clinical outcomes

It is important to ensure that UEC and acute capacity is being used as efficiently and productively as possible. This includes the NHS, local government and other system partners working together to improve the timeliness of discharge from hospital and community settings.

Learning during 2023/24

Actions taken in Year 1 of the UECRP to improve post-pandemic productivity have demonstrated a length of stay reduction in overnight emergency admissions of over 4% over 2023/24.

Health and care systems across the country have driven length of stay reduction through initiatives such as:

- Using the discharge ready date (DRD) metric (first published in November 2023) to understand the proportion of patients not discharged on the same day as they are clinically ready for discharge (that is, no longer meet the criteria to reside), the average length of stay, and the distribution of those delays (that is, the proportion discharged 1 day, 2–3 days, 4–6 days, 7–13 days, 14–20 days and 21+ days after their DRD). These data support systems to understand variation both between trusts and between local authority areas, and to identify where to target improvements.

- Implementing and maturing their care transfer hubs to manage discharges for patients with more complex needs. A Sheffield University NIHR review of reviews – with acknowledged limitations of the evidence base – found evidence in the published literature that care transfer hubs show promise both for patient flow and UEC performance and for quality of patient care, in areas such as reducing all-cause mortality, hospital readmissions and ED visits.

These learning have informed the planning guidance requirements and the supporting delivery actions set out below for 2024/25. Further evidence is set out in case studies and links throughout this section.

Based on evidence from last year, key supporting actions for 2024/25 include:

2A. Reduce admitted and non-admitted patient time in emergency departments

- Service providers (in and out of hospital) working together to continue the focus on initial assessment. Continue to increase the proportion of assessments received within 15 minutes, and to increase the proportion of patients redirected to alternative services such as urgent treatment centres, SDEC and acute frailty services, as well as urgent care response and virtual wards.

- Trusts ensuring that their medical model of care for the first 72 hours is optimised to eliminate the longest waits in the ED.

- Building on the evidence that inpatient flow interventions are an effective way to decrease ED wait times, systems working with providers to improve flow into and through acute beds by reducing excess length of stay and variation in high volume, high bed use pathways.

- Trusts seeking to understand their non-elective length of stay in key medical specialties, particularly respiratory and cardiology, and how they compare to the national mean and best in class via GIRFT model hospital datasets. Where evidence-based, robust clinical pathways exist (for example, fractured neck of femur, stroke, STEMI, AF), trusts can review whether clinical pathways currently meet key time stamps and take steps to monitor current levels of adherence as well as instigate plans to improve this.

- Trusts ensuring critical interventions during a patient’s in-hospital stay are in place, delivered in a timely way. This includes:

- a review by a senior decision-maker within the first 12 hours in hospital

- early planning and conversations around the patient’s anticipated discharge needs with full involvement of patients, carers and families in line with statutory guidance on hospital discharge and community support

- a care plan involving the patient and family/carer, and assessment against patient-centred questions

- a daily ward and board round (including weekends) on each ward.

- Trusts reviewing and auditing their internal professional standards, using the ECIST guide as a starting point.

- Actions to address the long waits that occur for many mental health service users are also beneficial, including:

- systems building on the successful rollout of psychiatric liaison services to all Type 1 EDs by working towards the ambition of responses within 1 hour of referral

- systems and providers, including local government, reducing mental health patient time in ED by tackling long length of stay of patients in acute beds waiting for transfer to a mental health bed, and the length of stay for those in mental health beds

- systems, including local government, focusing on improving whole pathway patient flow through mental health, including dedicated improvement action on discharge as set out in the 100 day mental health discharge challenge and GIRFT programme.

Case study: Lincoln County Hospital, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust – admitted pathway criteria to admit audit tool

Lincoln County has had long-standing challenges with exit block. Working with ECIST, it developed a pilot to incorporate the criteria to admit (CTA) audit tool into its standard admission processes, via a designated shift within the consultant rota, 8am to 6pm, 7 days a week.

The CTA consultant reviewed all patients with a plan to admit to an inpatient bed, including those who had been seen by the acute medical or specialty teams. If the patient had improved clinically, or were deemed not to meet the criteria at the time of review, then alternatives to admission were sought.

Early findings from the pilot have shown that this shift reduces admissions by 5–10 a day – approximately 8–16% of total admissions. Findings from an initial CTA audit suggest that over a week this equates to approximately 50 fewer admissions than pre-pilot with a resultant saving of 260 bed days a week. Every admission avoided also results in a decrease in bed wait time for the remaining admitted patients, improving overall performance as well as outcomes for those patients.

Case study: Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital – non-admitted pathway senior decision-makers

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital prioritised a focus on the non-admitted pathway mostly utilised by walk-ins, identifying that ED crowding had a negative impact on efficiency and hypothesising that improvements in this area would yield multiple gains downstream.

Following a review of the ambulatory pathway model it established that placing a senior decision-maker (wherever possible at consultant level) as the first point of contact for the patient would yield the greatest dividends in terms of making better use of ED alternatives, ensuring patients received more guided work-ups, and resulting in more rapid turnarounds for those patients seeking primary care and not UEC.

This team was put in place in November 2022, made up of nursing, medical and healthcare assistants, and has seen a massive step change in the non-admitted pathway, with corresponding change in 4-hour performance.

2B. Reduce the number of patients still in hospital beyond their discharge ready date (DRD)

- Acute providers continuing to improve in-hospital processes to improve timeliness of discharge, including early discharge planning from the point of admission and early involvement of care transfer hubs where patients are likely to have more complex discharge needs.

- ICBs and local authorities, working with acute trusts and community/social care providers maximising the effectiveness of their care transfer hubs, and ensuring their care transfer hubs become increasingly mature over the course of the year. This includes extending the scope of care transfer hubs to discharge from community beds where practical and ensuring effective governance for care transfer hubs, including a senior responsible officer across the NHS and local authority, clear escalation routes and reporting, underpinned by high-quality, shared data. This includes ensuring the right mix of nursing, therapy and social work professionals are available to work directly with patients, families and carers to plan timely and effective discharge, with appropriate support for recovery and reablement, and effective arrangements through both ward-based teams and community/social care providers to ensure timely and effective transfers of care. Care transfer hubs should work closely with ward-based teams to ensure a ‘Home First’ approach to discharge, with a focus on strength-based, person-centred decision-making and full involvement of patients, carers and families.

- Systems, including both the NHS and local authorities, implementing trusted assessments to reduce duplication and ensure information is shared appropriately through the pathway. Care transfer hubs work best when they have the authority, knowledge of the local care landscape, processes and staffing mix to make effective decisions that provide the right support to go home, based on patient need and agreed by health and social care providers, supported by clear processes for case management from the point of admission until discharge, and escalation of challenges. Consideration may be given to holding a waiting list for each discharge pathway, so that if a discharge fails, the next person who could take up that bed or package of care is identifiable.

- Systems and providers ensuring patients no longer meeting the criteria to reside are discharged as early as possible in the day. Actions to deliver this include working with services outside the hospital to co-ordinate an early discharge, and avoiding bedding discharge lounges or, if there is no option, reverse boarding them with patients due for discharge the next day, reducing acuity (and therefore risk) within the discharge lounge.

- ICBs and local authorities, working with acute trusts and community/social care providers, using the new discharge metrics (derived from discharge ready date [DRD] data) and data on reasons for delay to identify how to increase the proportion of patients discharged on their DRD (that is, when they no longer meet the criteria to reside) and how to reduce the average length of discharge delays. This includes tackling the longest delays that are likely to be associated with poorer outcomes for patients.

Case study: South and West Hertfordshire – single point of contact

The Single Point of Contact (SPOC), South and West Hertfordshire’s ‘care transfer hub’, merges health and social care discharge functions into one place to facilitate people to be discharged from hospital rapidly, safely and appropriately.

Operating since 2020, professionals from Hertfordshire County Council’s Integrated Discharge Team, Central London Community Healthcare NHS Trust and West Hertfordshire Teaching Hospital NHS Trust work together to support on average 700 discharges a month; the majority of which are via discharge to assess. This is more than double the number of people discharged with support in 2019. The SPOC uses a ‘discharge information form’ completed by health professionals to fully understand a person’s needs and take a strengths-based approach to supporting discharge to the most appropriate place, preferably home.

The SPOC enables:

- cross-organisation, person-centred triage and decision-making of referrals

- the person and their family carer to be involved in their discharge planning from the point of admission

- the person to be discharged with the support most appropriate for them with assessment being undertaken outside the acute hospital, achieving better long-term outcomes

- simplified referral and discharge processes, reducing the amount of time a person spends in hospital when there is not a medical reason to do so

- effective use of SHREWD, a shared data tool, to monitor real-time demand and escalate any issues or challenges, while also feeding in data to the ‘DTA dashboard’ which is used to inform system-level decision-making on capacity and demand activity

- West Hertfordshire to operate within national guidelines and best practice

The SPOC also work with the Impartial Assessor (Hertfordshire Care Providers Association) which supports timely transition from hospital to care homes by undertaking any assessments on behalf of the home and ensuring communication at every step.

Case study: Waltham Forest – care transfer hub

Waltham Forest’s care transfer hub has representation from community services, their acute provider and the voluntary sector. It also has local authority input from Waltham Forest (including a dedicated broker and housing representative), Redbridge and West Essex to input into multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion and provide updates on each patient awaiting discharge.

It has found success from its care transfer hub model for a number of reasons. It has established strong, partnership ways of working, which include twice daily attendance at MDT discussions that are held virtually. Data sharing agreements are also in place to support access to partner’s systems and it has effective case management processes. Since introduction of its hub, Waltham Forest has achieved more discharges down Pathway 1 and fewer Pathway 3 discharges.

Waltham Forest also operates an in-house ‘bridging service’ where support workers and co-ordinators as part of the hub can provide care for Pathway 1 Waltham Forest patients for up to 5 days. This can support people to be discharged more quickly; an assessment of care needs is subsequently taken at home, the patient has quick access to equipment and reablement is provided at each care visit. It has found that as well as reducing length of stay in hospital, this has resulted in better outcomes for the patient.

Case study: Swindon – care transfer hub

In January 2023, Swindon launched its care transfer hub with representatives from the ICB, Swindon Borough Council, Great Western Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, First City Nursing and acute and community therapy leads. The aims of introducing the hub included improving patient experience, streamlining referral processes and applying an MDT approach to triaging referrals and facilitating timely discharge to improve flow.

People who are identified as individuals who may require additional support on discharge are referred electronically to the care transfer hub by wards. This can happen at any time during their admission, from both acute and community hospital wards. Each day, including weekends, the MDT comes together to make a decision for their discharge pathway and relevant referrals are passed onto the appropriate team. The hub also holds daily NCTR calls to discuss discharges due that day and the following day, where actions are set to facilitate discharge and cases can be escalated.

The hub is also underpinned by a strong ‘Home First’ model. Individuals who are discharged down this pathway will be supported, via a multidisciplinary approach, for ongoing health and social care assessments. Staff make joint visits to minimise duplication and delays and, if required, ongoing care will be arranged for the individual. There is a system response in place under the SOP if there is a risk of readmission to maintain safety.

2C. Reduce length of stay in community beds

- Systems continuing with the actions identified to increase productivity of community bed-based services following the maturity self-assessment undertaken in July 2023.

- Systems extending the implementation of best practice flow principles to community beds.

- Systems reducing discharge delays from community bedded units through timely access to ongoing packages of care that support transition and continuation of rehabilitation and reablement at home, reducing days away from home.

- ICBs and local authorities exploring ways to track length of stay in intermediate care services locally, helping to improve the use of bedded and non-bedded intermediate care for people whose rehabilitation and reablement needs requires it.

2D. Improve consistency and accuracy of data reporting

- Systems ensuring all trusts are consistently and accurately recording key metrics, including SDEC activity in the Emergency Care Data Set (ECDS) and the Ambulance Data Set.

- All NHS-commissioned community bed providers being registered and submitting regular data to the Community Discharge SitRep, with updates to the dataset in mid-2024.

- All acute and specialist providers ensuring that they are submitting high-quality and timely DRD data for monthly publication, and that reasons for discharge delay are captured accurately in SitRep or Faster Data Flow returns.

- Systems ensuring system co-ordination centres are fully embedded, including operational standards and digital ‘near real-time’ footprint.

- Systems having arrangements in place to disaggregate data based on age, to understand demand and monitor performance for children and young people.

Priority 3: Developing services that shift activity from acute hospital settings to settings outside an acute hospital for patients with unplanned urgent needs

During 2024/25, health and social care systems need to build on work underway to develop services that support a reduction in attendances and admissions to hospital, and to improve access to those services.

ICBs should work with local authorities, social care providers and VCSE partners to ensure an integrated approach to providing health and social care, where necessary, for people with urgent care needs – and to continue to strengthen proactive care for people most at risk of emergency admissions, including care home residents and people receiving domiciliary social care.

Parents and carers should be provided with access to clear, accurate information about common illnesses in children and young people, promoting self-care and access to the right care at the right time.

Learning during 2023/24

In Year 1 of the UECRP, health and social care systems have been working to build capacity that supports people to have their urgent needs met outside a traditional ED.

Zero-day length of stay (0LoS) has increased year on year since the introduction of a mandate to support SDEC service provision 12 hours a day, 7 days a week.

There has been a 11% growth in 0LoS emergency admissions during 2023/24, attributed in the majority to SDEC growth. Many systems have successfully introduced and matured their SDEC services to reduce both wait times and admission rates for some patients when compared to an ED or acute medical unit.

This learning has informed the planning guidance requirements and the supporting delivery actions set out below for 2024/25. Further evidence is set out in case studies and links throughout this section.

Based on evidence from last year, key supporting actions for 2024/25 include:

3A. Increase referrals to and the capacity of urgent community response (UCR) services

- Systems increasing referrals to, and number of patients treated in, UCR services, building on the success to date of these services in preventing patient deterioration and reducing pressures on other health services. This work has been most successful where:

- there has been a focus on referrals from wider system partners including 999, NHS 111 and care homes to improve step-up pathways as forms of both attendance and admission avoidance

- technologies (including point of care testing) have been implemented to optimise existing capacity

- referral pathways from technology enabled care (TEC) providers and SDEC have been supported.

Case study: Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust – urgent community response

The (urgent community response) UCR service in Oxford, part of Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, delivers crisis response for people who are at risk of a hospital admission in the next 24 hours. It provides assessment, treatment and support in the patient’s home to avoid a hospital admission.

To help keep people at home, Oxford’s UCR team have developed strong collaborative working between themselves and secondary care. A ‘consultant-on-call’ service has been introduced where the UCR clinicians have direct access to an Oxford Health consultant geriatrician, which enables a clinical conversation to take place. Together they devise an agreed treatment plan for the person, often resulting in the person remaining at home instead of being conveyed.

Patients are reporting positive experiences of receiving care through UCR with patients saying the service is “amazing”, “brilliant”, “excellent” and one patient commenting that they were “grateful for remaining at home”.

3B. Ensure all Type 1 providers have an SDEC service in place for at least 12 hours a day, 7 days a week

- Systems continuing to develop access components, and encourage specialist SDEC development (such as frailty or paediatric) according to local demographic need.

- Systems, including ambulance trusts, increasing utilisation of SDECs by:

- increasing the proportion of patients with direct access, increasing direct referrals from outside the ED (NHS 111, 999 and primary care)

- reducing variation in the proportion of ED patients who are treated through the SDEC

- implementing the minimum standards of delivery outlined in the SAMEDAY strategy.

- Providers working to improve consistency of reporting SDEC into ECDS by March 2025.

Case study: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust – same day emergency care access improvement project

Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust has focused on improving access to same day emergency care (SDEC) across both its sites, St Mary’s Hospital and Charing Cross Hospital. Direct electronic booking was introduced in June 2023, allowing the local NHS 111 provider and the ambulance trust emergency clinical assessment service (ECAS) to book patients directly into a slot at either SDEC unit without the clinician having to telephone the unit first.

Utilisation of this pathway showed a slow but steady rise as clinicians became familiar with the service – supported by a range of engagement efforts – rising from an average of 15 referrals a month to 55 referrals a month, an increase of over 250%. Associated benefits include a reduction in clinical touchpoints, unnecessary triage and multiple handovers of care, as well as alleviating pressures within the ED.

Following the success of the direct electronic booking pathway, St Mary’s then introduced a direct access trusted assessor model for the ambulance service, whereby paramedic crews could bypass ED and convey patients direct to the SDEC unit. Direct conveyances have increased from an average of 20 a month at pilot launch to 36 a month in March 2024. Imperial has since gone live with direct access at Charing Cross as well.

3C. Ensure all Type 1 providers have an acute frailty service in place for at least 10 hours a day, 7 days a week

- Acute frailty units implementing the minimum standards in the FRAIL strategy supported by initiatives to increase patient flow through direct access, front door frailty identification, timely access to diagnostics and access to specialist clinicians where appropriate.

- All acute trusts implementing a comprehensive geriatric assessment at the front door, to increase the proportion of patients over 65 with a Clinical Frailty Score.

- Systems working to understand and reduce variation in care home residents’ attendances at EDs.

Case study: Hillingdon Hospital – frailty assessment unit

Recognising the disproportionate impact that older adults with frailty have on ED performance, admissions and hospital bed days, Hillingdon Hospital used 2022/23 winter funding to develop its Frailty Assessment Unit in order to address these issues.

Following a successful pilot a business case was approved for the unit to continue operating under the new model throughout winter 2022/23 and is now business as usual. Through a combination of avoided admissions and reduced length of stay for patients admitted through the Frailty Assessment Unit, they were able to show a reduction of 127 bed days occupied by inpatients with a Clinical Frailty Score of 5 or more compared to the previous winter.

The frailty team continues to see between 150 and 200 patients a month including 26% of all patients with a Clinical Frailty Score of 6 or more who attend ED and SDEC, and have received good or very good feedback on 100% of the friends and family surveys.

3D. Provide integrated care co-ordination services

- ICBs and local authorities working to understand the total demand for services that provide an alternative to an ED attendance for urgent care needs, complemented by a review of capacity across all relevant services, including UCR, community pharmacy and SDEC. Linking this to BCF demand and capacity planning for intermediate care.

- Systems working towards having core operational integrated care co-ordination structures as a minimum by October 2024, to help ensure the best response to patient needs, with a focus on paramedic access to clinical advice to support alternative pathways to ED.

- Systems ensuring they have plans to surge acute respiratory infection (ARI) capacity as required. For some systems, this may include the provision of ARI hubs, including paediatric ARI hubs for children. Analysis of ARI hub appointments from December 2022 found that ARI hubs can reduce pressure on ED attendance and free up capacity in general practice while improving same day access.

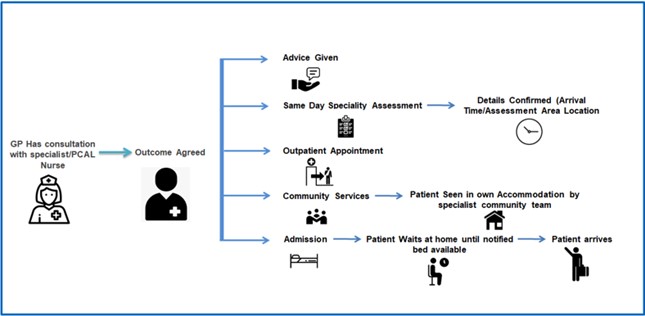

Case study: Leeds – Primary Care Access Line

The Primary Care Access Line (PCAL) model aims to provide access to a range of services to prevent ambulance conveyance or attendance at ED, specifically for health and care professionals (HCPs), often GPs and ambulance CAS. HCPs are able to have a clinical conversation with PCAL and receive guidance such as direct booking and referrals to SDEC and other secondary care services, as well as pathways to community and out-of-hospital services. The model is nurse-led but the team are drawn from a variety of acute and primary care backgrounds.

The service has grown from 10 calls a day in 2003 to 225 calls a day (over 80,000 calls a year) in 2022/23, with access to over 50 clinical pathways, and Leeds showing lower than average ambulance waits in ED compared to regional peers. The service has particularly high levels of positive feedback from Yorkshire Ambulance Service clinicians and has been nominated by users for national awards.

Annex 3: Joint working between the NHS and local government

The effectiveness of UEC services relies on the NHS, local authorities, and providers of health and care services working together across the UEC pathway. Throughout the last year, there have been excellent examples of ICSs bringing together organisations across health, social care and wider community services to prevent avoidable hospital admissions, improve discharge from hospital, community and mental health settings, and improve outcomes for patients.

During 2024/25, the NHS and local authorities, working with the full range of relevant providers, VCSE organisations and patients, families and carers, will need to build on and strengthen this joint approach, working together with the following goals:

Build on progress in reducing discharge delays and improving discharge outcomes

- Further improvements in demand and capacity plans for intermediate care, based on reviewing patterns of demand and capacity in Year 1 and Year 2 and ensuring demand and capacity plans link with both NHS planning assumptions for UEC and local authority planning assumptions for adult social care.

- Further optimisation of care transfer hubs by implementing the 9 priority areas of focus as set out in the Intermediate care framework for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery following hospital discharge, with a particular focus on cohorts with the most complex needs, including patients experiencing homelessness, complex dementia or mental health conditions.

- Enhanced focus on improving discharge from community settings, building on the work done on implementing care transfer hubs in acute settings.

- Sustained focus on early discharge planning and 7-day discharge arrangements, working across hospital wards, care transfer hubs, care providers and care homes.

- Embedding a ‘Home First’ approach to support recovery at home.

A stronger focus on preventing avoidable hospital admissions

- Improving proactive care through collaboration across the NHS, adult social care and related services for people most at risk to prevent people’s needs from escalating; for instance, through falls prevention, home adaptations and assistive technology, telecare, and healthcare input into residential and nursing home settings.

- Providing rapid community-based forms of crisis response to avoid, where possible, acute hospital stays, including strengthening social care input into virtual wards.

Joint planning of workforce interventions

- Developing the therapy and reablement workforce needed for high-quality intermediate care.

- Developing the workforce needed to provide specialist care for people with more complex needs (for example, dementia nursing).

- Implementing new workforce models as set out in the Intermediate care framework for rehabilitation, reablement and recovery following hospital discharge

Case study: Stockport Place, Greater Manchester Integrated Care System and Stockport NHS Foundation Trust/Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust – high intensity use service

Stepping Hill Hospital ED is supported by a high intensity use (HIU) service, which identifies the top 250 A&E attenders within a 3-month period for dedicated support. The service is non-punitive, non-medical and is focused on supporting people with ‘chaotic’ or difficult lives while offering social, emotional and practical support. The impact of HIU services is significant, with a broad estimate of between 300 and 400% ROI, as well as the immeasurable benefits to patients:

James, 47, lived alone and had Crohn’s disease and was on a waiting list for a stoma, but his surgery was cancelled. In this time, his mental health rapidly declined, and he attended ED 80 times in 12 months, sometimes twice a day – the majority by ambulance – and resulting in 11 non-elective admissions.

The HIU service adopted an assertive outreach approach, working on meeting his wider social needs including linking into the Crohn’s Network for peer support. Furthermore, the HIU lead expeditated the necessary procedure and joined up his care. James’ attendances to A&E stopped altogether and his mental wellbeing has improved incredibly. He now feels he can live life to the full and is very grateful for the intervention, saying “I know I can, but I don’t want to have to attend A&E ever again.”

To support these objectives:

- ICBs and local authorities will already be planning how to make most effective use of the BCF, including the £1 billion Discharge Fund (an increase of £400 million over 2023/24), to provide services that best meet people’s needs for community-based care and support and maximise health and independence

- NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) will continue to work with the NHS and local authorities with the greatest UEC pressures to help develop system-wide improvements, building on the work of the Discharge Support and Oversight Group but with an enhanced focus on admissions avoidance and on flow through intermediate care. This will include further work to spread good practice in capacity and demand planning for intermediate care and in the use of care transfer hubs

- NHS England and DHSC, through the joint Discharge Support and Oversight Group, will use data on discharge delays and reported reasons for discharge delays, alongside other available data, to measure progress across the NHS and local authorities in improving discharge, including improving flow through both bed-based and home-based intermediate care, whether NHS commissioned, local authority commissioned or jointly commissioned

- NHS England and DHSC will go further to align and improve the universal and targeted support available through NHS England and the BCF support programmes

Annex 4: Learning from urgent and emergency care tiering

Analysis of the urgent and emergency care (UEC) tiering approach has shown that Tier 1 and Tier 2 improvement over the last year has been material, particularly in 4-hour performance.

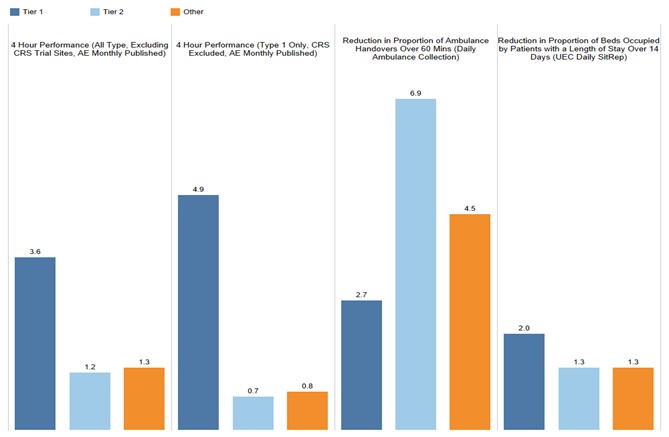

Although all tiers have shown a percentage point increase in key metrics since UEC tiering support commenced. Tier 1 and Tier 2 systems with a Type 1 ED have shown a greater percentage point increase in some of these metrics. As can be seen in the chart below, Tier 1 trusts saw a 3.6 percentage point improvement in ‘All Type’ 4-hour performance and a 4.9 percentage point improvement in ‘Type 1’ performance. Tier 2 systems in turn showed a greater improvement than Tier 3 in reduced ambulance handover delays.

Improvement by percentage point in tiering metrics (original cohort)

Early findings from reviews of tiering support indicate that this approach works best where:

- strong system leadership provides system accountability and assurance of delivery and long-term, sustainable improvement

- collective, system-wide improvement is delivered through collaboration across the entire UEC pathway, including primary care, community services and mental health

- improvement approaches and performance oversight are supported and driven by data

- prioritisation of improvement opportunities is focused on the interventions that will have the greatest patient impact