What is peer support?

Peer support is a supported self-management intervention. It happens when people with similar long-term conditions, or health experiences, come together to support each other – either on a one-to-one or group basis. It is enabled through relationships that build mutual acceptance and understanding.

Peer support is a valuable resource for people and their families and carers; empowering them to take ownership of, and have more control over, their health and wellbeing. It enables people to develop the knowledge, skills, and confidence to self-manage and address other issues that might be affecting their health, such as loneliness or self-esteem.

The power of peer support lies in connecting people with shared experience to create an encouraging, inspiring, and safe space. This personalised, holistic support focuses on wellbeing and understanding lived experience, rather than clinical interventions.

Peer support increases individual and community capacity, and resilience. Other supported self-management interventions, such as self-management education and health coaching, can be incorporated alongside peer support where appropriate.

Models of peer support

There are several ways in which peer support can happen, meaning it can be tailored to people’s needs in the right place, at the right time.

Online and telephone support

Sometimes people find it best to connect online or on the telephone; one conversation might be all it takes to help a person start to feel better.

One-to-one support

One-to-one support can be online or in person. It can also be alongside one another such as activities like going for a walk together.

Informal group support

Groups with shared common interests often come together to offer each other peer support, for example, gardening or crafting clubs.

Formal group support

Formal, commissioned support groups offer more structured support, for example, perinatal mental health, or addiction support groups.

Why is peer support important?

Peer support does not replace the need for effective clinical advice, support and information. It provides people with a supportive community that enables them to play a more active role in the ongoing management of their health and wellbeing.

Peer support develops people’s knowledge, skills and confidence, enabling them to take steps to live as well as possible with their condition(s). In turn it can help to reduce pressure on the health and care system – people who lack the confidence to self-manage their health and wellbeing are 10 times higher utilisers of services.

By enabling access to peer support and using the skills and expertise of people with lived experience, the health and care system has an opportunity to empower people to make more informed and conscious choices in self-managing their long-term or acute condition(s).

There is a strong evidence base for supported self-management and studies into the specific impact of peer support indicate:

- It improves quality of life, provides experiential knowledge, develops supportive, trusting and therapeutic relationships, provides emotional support and information [1].

- It can support people with long-term conditions and contributes to wellbeing and improved clinical outcomes, resulting in cost savings to health and social care [2]. For example a peer support scheme for people with mental health issues in Nottingham contributed to a 14% reduction in inpatient stays, with savings estimated at £260,000 for a cohort of 247 people.

- The financial benefits of employing peer support workers exceed the costs, in some cases by a substantial margin.

[2] Realising the Value (2016), At the heart of health: realising the value of people and communities. Available online: https://www.nesta.org.uk/report/at-the-heart-ofhealth-realising-the-value-of-people-and-communities/)

Emerging studies have also shown that when peer support is embedded in clinical pathways it can bring about a number of benefits. For example, a recent study looking at the impact of cancer peer support interventions on psychological empowerment concluded that: “Peer support groups should be seen as an important element in cancer care and clinical practice and be more systematically involved in cancer care.”

What does good peer support look like?

As outlined in Figure 1 below, peer support can take place in a group, one to one, face to face or virtually. It can be a commissioned service, led by the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector or simply be a group of people who meet informally. It often develops organically and is championed by passionate people who want to share their experiences to help others.

Whatever the delivery model, the key principles for effective peer support remain the same. The following principles have been developed drawing on examples of good practice in peer support:

- Shared experience is at the heart of peer support. People with lived experience are involved in coproducing peer support and defining its purpose and values.

- It is accessible and inclusive, enabling a diverse range of people to feel accepted and understood.

- Everyone is different and the strengths, values, needs and feelings of others are recognised.

- People feel they have a safe space to be authentic and to share experiences/expertise, including health and care staff who may attend.

- It is reciprocal – everyone can contribute to and benefit from the relationship(s) they build through peer support.

- People are supported to use their strengths and skills, find solutions, manage challenges and meet their personal goals.

- It is flexible and adaptive to respond the evolving needs and goals of those accessing peer support.

- People are encouraged to access clinical advice and support when they have an unmet medical need, helping to ensure people get the right kind of support they need at the right time.

Peer support – a holistic approach

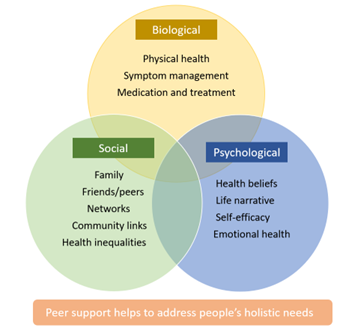

People’s health and wellbeing is not simply defined by their medical condition(s) or health needs. Social and psychological factors also play a part in people’s ability to self-manage their condition(s) – this is demonstrated in the biopsychosocial model of care in Figure 1. Peer support is an effective way of supporting people with their holistic needs, including every day self-management for symptoms and wider emotional and social needs.

Figure 1 – biopsychosocial model of care

Figure 1 – biopsychosocial model of care – shows three linked circles and how they overlap and interlink. The circles are titled biological, social and psychological and represent the different things that have an impact on people’s health and wellbeing. The circle titled biological, includes physical health, symptom management and medication and treatment. The circle titled social, includes family, friends, peers, networks, community links and health inequalities. The final circle is titled psychological and includes, health beliefs, life narrative, self-efficacy and emotional health. This diagram shows that peer support plays a part in addressing all of these needs.

The model also helps us understand how health inequalities have a significant impact on people’s health outcomes. A 2016 study that explored peer support as a means of reaching more marginalised communities found it to be “a broad and robust strategy for reaching groups that health services too often fail to engage” [3]. It also has the potential to improve experience and emotional aspects for specific groups, including carers, specific age groups and ethnic groups.

Peer support can be a powerful and adaptable enabler in connecting people with shared experiences and this could include providing peer support to people from deprived areas, people leaving the criminal justice system, people with disabilities or from minority ethnic groups living with long-term conditions, or at increased risk of developing them.

Example: Sistas Against Cancer, Nottingham

Sistas Against Cancer was established by women from ethnic minority communities who were going through a cancer journey. They had limited awareness of the support services available to them or did not identify with the existing peer support groups available for women with cancer locally.

The women met at NHS clinics or were introduced via Self Help UK and black and ethnic minority cancer communities. Working in partnership with a range of health professionals, Sistas Against Cancer offered its members a variety of support activities, including chair-based exercise classes, sessions on nutrition, cancer awareness talks, and medication and mental health advice.

The group also worked with the Oncology department at Nottingham University Hospital Trust to improve availability of culturally appropriate wig services and pressure garments in a wider variety of skin tones. Regularly gathering the views of their members, Sistas Against Cancer shares its feedback with services on how to become more welcoming and accessible to patients from ethnic minority communities.

Models of peer support

There is no one ‘right’ or ‘best’ model of peer support. Models vary depending on the circumstances, skills and needs of the people involved and the resources available. Involving people in the development and delivery of peer support is the best way to ensure that the model is right for those who will access it.

Often peer support develops organically, beginning with an individual or group of people who are passionate about supporting others, for example:

- A group of people with the same condition/experience finding each other in person or online (twitter, online forums etc.) and deciding to get together or provide one-to-one ‘buddy’ support.

- People meeting on a self-management education course and deciding to keep meeting/stay in touch after the course has ended, either as a group or one to one.

- A volunteer led and social group in a community venue that provides a space for people with similar health conditions.

- A voluntary, community and social enterprise organisation identifying a need and creating/supporting a group.

Example: Kidney Care UK

Kidney Care UK runs an online forum for young people, aged 18 to 30, with chronic kidney disease, via Facebook. The forum is for patients only and provides a safe space – active and timely moderation are essential to keeping it a safe space. There are several trained supporters, but support can come from anyone in the group.

However, peer support can also be provided in a more structured way as part of a specific pathway and be formally commissioned or championed by health and care professionals, working with people with lived experience. For example:

- A social prescribing link worker or a health and wellbeing coach or a health professional identifying people with similar interests/concerns and bringing them together.

- Peer support provision built into a structured self-management education course, for example, for managing Type 1 diabetes.

- Peer support workers employed to provide one-to-one support to people, as part of a pathway or service, for example, peer support for mental health recovery.

- A voluntary, community and social enterprise organisation commissioned to provide peer support services as part of a pathway, for example, in drug and alcohol services.

Example: Evolving Care

Evolving Care, for people with HIV in London, emphasises working in partnership with voluntary sector providers to embed peer support in clinics as an integrated part of the care pathway.

All clinicians in the service are aware of this service and routinely refer. Peer support sessions integrate with clinical appointment times and include peer support workers as part of the clinic’s multidisciplinary team.

Signposting and referring people to peer support

People can benefit from peer support at different times in their health and wellbeing journey; there’s no universal best time to explain the benefits of peer support.

Peer support is a form of personalised care, and it is important that people should be able to access it at the time that is right for them. This could be explored in personalised care and support planning conversations, and at various points in someone’s care pathway such as point of diagnosis, discharge, and/or regular reviews.

Depending on the availability of local peer support, and commissioning arrangements, health and care professionals may be able to directly refer people to peer support. Other routes to access may include self-referral and signposting to local services. Social prescribing link workers in primary care are well placed to advise people on the local provision of peer support to address social and emotional needs.

Example: Sugarbuddies

When a West Hampshire Community Diabetes Service helpline was overrun with requests from people recently diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, it became clear that a separate peer support service was needed to support people through the early stages. Subsequently, Sugarbuddies, a one-to-one peer support buddying service was born.

The peer support provided by the buddies complements the diabetes service models across the region. People newly diagnosed, or with established diabetes, self-refer to Sugarbuddies for peer support, having found out about the buddies via their GP practice or their specialist team.

Since the introduction of Sugarbuddies, there has been a reduction in demand for queries that are better answered by someone with lived experience.

Peer support can be effective in supporting people to ‘step down’ from another service, where they still need some extra support to help them self-manage.

Considerations when setting up or commissioning peer support

Peer support services can be set up alongside other supported self-management interventions, such as self-management education and health coaching, providing a complementary menu of options that can be tailored to individual needs to improve people’s knowledge, skills and confidence.

When considering the most appropriate approach to setting up or commissioning peer support it can be important for commissioners and service development leads to consider a range of options and factors that can impact on the success of peer support services. The questions in the checklists below provide some helpful prompts when setting up peer support at neighbourhood, place, and system level.

1. Making the case for peer support

- How can peer support benefit your local population and what do you expect the outcomes of peer support to be for the population and the local health and care system?

For example, peer support could be introduced for people recovering from a heart attack, to support with their cardiac rehabilitation. Or, if musculoskeletal disease is identified as a high local population health need, peer support could be introduced to support people with pain management.

- What is already out there in the local health and care system that works well and could be scaled up or used as a model to build upon?

This may include VCSE sector led peer support or peer support in other public services, for example, local authority led work.

- What priorities will peer support help you to tackle?

Are there particular groups you think need additional support to develop knowledge, skills and confidence around?

- How does peer support contribute to your strategic objectives?

For example, increasing proactive personalised care, supporting people with multi-morbidities, preventing escalation of disease, addressing health inequalities.

2. Involving people and stakeholders

- How will you involve people with lived experience, including peer leaders, in the coproduction of a peer support service to ensure the model and approach meets people’s needs?

For example, you could involve people through surveys, focus groups, going to community groups, inviting people to be part of the design team.

- What support and specialist knowledge do you need from health and care professionals?

For example, including a diabetic nurse in developing peer support or a health and wellbeing coach. This can help give people accessing peer support and clinical staff confidence in understanding how clinical concerns or health information will be addressed.

- How will you work with other stakeholders in developing and delivering peer support at the right time and in the right place for people?

Local authorities and the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector are key stakeholders who may already have effective mechanisms in place for delivering peer support, for example, local groups for people with specific conditions or specific populations.

- Who else is championing this approach and how can they contribute expertise?

For example, local residents providing community-based peer support, or clinical staff who advocate for peer support. These are your champions and can help.

3. Developing a quality and sustainable peer support service

- What resources do you need for sustainable peer support model?

This will vary depending on the model you use but could include salaries for peer support workers, access to local venues, IT resources.

- How will you ensure people are fully supported to participate in peer support?

For example, if you have a model that uses the skills of volunteer peer leaders, they may need training, mentoring and expenses reimbursing.

- What resources can you use that are already in existence from other peer support projects and national initiatives such as the Peer Leadership Development programme?

Your local stakeholders in the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector and local authorities may have good practice resources and information to share.

- How will you quality assure peer support so that everyone is confident about accessing and referring/signposting to it?

This is something you can explore in conversation with people with lived experience and stakeholders, by considering the standards and scope of peer support and how progress and impact will be monitored.

4. Integrating peer support into other services and interventions

- What other support/resources do people need to support them to self-manage?

This will depend on different needs, models and pathways but could include access to health coaching, self-management education or access to self-monitoring devices, for example, blood pressure machine.

- Which pathways and services could be improved by offering peer support to people?

This could be linked to conditions where behavioural factors play a part in the progression of disease for example chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or heart disease, or could be supporting specific groups of people who face health inequalities, for example carers.

- How will people find out about peer support and how to access it?

This can be explored in conversations about the development of peer support and the model. It could include self-referral, signposting and referral options.

- What role will health and care staff play in offering people peer support and how will staff be made aware of it?

For example, there may be a benefit to having a clinician involved to provide advice and health information, for example, on pacing, taking medication etc.

Evaluating the impact of peer support

There are a range of ways you can measure the impact peer support is having on people and example tools are outlined in the measuring supported self- management section of the NHS England website. This could include gathering data on the benefits to those accessing the peer support and also on the use of services, for example those getting peer support may need fewer clinical appointment as a result of feeling more supported.

Useful resources

Case studies

There is a variety of case studies about peer support available on the supported self-management Future NHS workspace (you will need to register for a Future NHS account to access the workspace).

Evidence, resources and reports on peer support

- Person centred care – National Voices

- Realising the Value Programme

- What is peer support and does it work? – National Voices

Examples of condition specific resources on peer support

- Guide to peer support services in HIV clinics

- Six principles of good peer support for people living with Type 1 diabetes

- Five principles of perinatal peer support

Publication reference: PRN00827