GP practices manage a wide range of patient requests every day, each requiring careful consideration to identify the most appropriate next step. Patients access services via telephone, the front desk and, increasingly, using online consultation (OC) tools. Practices must evaluate why help has been sought and triage the patient to the right services or health professionals.

Triage means understanding what kind of support is necessary; how quickly this should take place; and who is best placed to manage the patient or request. Clinical triage can help practices to allocate healthcare services according to individual needs, ensuring everyone receives the care most suited for them.

In line with national guidance from NHS England, parts of general practice moved to a digitally enabled ‘total triage’ system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Total triage meant all patient requests were screened remotely before being directed to an appropriate pathway or consultation type. Some practices used a more simplified form of telephone/video first with any patients who needed focussed examinations brought in later in the day to see the clinician they had already spoken to or a colleague.

There has since been a rebalancing with many practices moving away from total remote triage to blended triage models using new digital tools alongside traditional methods. The core digital offer in the GP contract means practices must promote and offer online consultation tools and secure two-way messaging systems (online messaging tools) to patients. Digital triage is now an established element of modern general practice and integral to the General Practice Improvement Programme.

This article should be read in conjunction with the related articles:

Key definitions

Key definitions include:

- Triage, where patient requests are screened by the practice and signposted to the next appropriate step in their care journey. This can be done by:

- appropriately trained non-clinical staff normally in the form of ‘care navigation’

- care coordinators

- clinical staff

- online consultation tools automatically processing or summarising information provided by patients

- Remote triage is carried out remotely using digital tools or the telephone:

- digital triage is remote triage that is carried out using digital tools such as online consultation (OC) tools, online messaging (OM) tools or other forms of secure two-way communication

- telephone triage is remote triage carried out using the telephone.

- Total triage – every patient that contacts the practice is first triaged before an appointment is arranged. All patient requests are screened and signposted by the practice to the next step of their care journey. Practices use a combination of both digital and traditional pathways to achieve this

- Digital triage – patients use digital tools such as online consultation (OC) tools (website or app), or online messaging (OM) tools to provide their care request prior to an appointment. This information is then reviewed by a clinical or non-clinical staff member, or automatically processed by the OC platform to direct patients to the relevant consultation type, service or self-directed care

- Total digital triage – a form of digital triage where every patient request is put through an OC tool. This means patients calling in via the telephone or presenting at reception with a care request have their information collected and inputted on their behalf into an OC tool for triage

Care navigation and triage

Care navigation is not new and describes the way patients or requests are signposted and directed from their initial point of contact. It is simplified from of general triage, but it is not the same as ‘clinical triage’ because it is often carried out by non-clinical staff.

Courses training non-clinical patient-facing staff in ‘active signposting’ have existed for some time. System suppliers have created care navigation templates to help fast and standardised data input. This is supported by Health Education England[1], which has developed a competency framework for care navigators.

Receptionists are often the first step in care navigation for patients, taking an integral role within any practice. Traditionally, receptionists process requests via the telephone or face-to-face when patients attend the practice. Care navigation can help the eventual clinical triage of patients if this is required.

OC and OM tools have added a new way for patients to access and request care. These tools produce summaries of the information provided by patients which can then be used to navigate or clinically triage patients to the next best step in their care journey.

OC tools have also developed their own short and easy-to-fill care navigation templates. Practices can use these to guide all their patient requests through their online consultation platform when patients are presenting via telephony or face-to-face. These short form care navigation templates within the OC tool enable staff to enter important information quickly without the need to fill out a detailed online consultation form.

National guidance and requirements

The GP contract sets out the requirements for promoting and using digital tools. These do not extend to using the tools when triaging patients. Similarly, there is no contractual requirement for a total triage system. Practices are encouraged to use a system that works most effectively for their own population.

Digitally enabled triage | What does good look like?

Patients will always need traditional access routes such as telephone or face -to face. This is essential for preventing worsening health inequalities. Practices now employ an ever-increasing number of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals through the additional roles’ reimbursement scheme (ARRS). Triage can be increasingly powerful and increasingly complex in equal measure.

Practices can now direct patients to the correct type of clinician far earlier in their care journey:

- practices receiving information via online consultation) tools now have more information at their disposal to drive decision-making

- they have a variety of communication channels to interact with patients via two-way online messaging tools

- digital tools can allow practices to request additional information readily using two-way messaging systems as part of the triage process

- some OC tools may feature automation to aid direct booking into pathways or services

Practices will differ in how they allow their patients to use OC tools, some will continually promote the use of OC tools as a primary method of contact, alongside traditional contact pathways, for both chronic and acute care requests, therefore processing hundreds of OC requests per week.

Others will limit the use of OC tools for acute on-the-day requests as part of their on-call system, with very little reliance on the systems outside of this, therefore, processing a small number of OC requests per week.

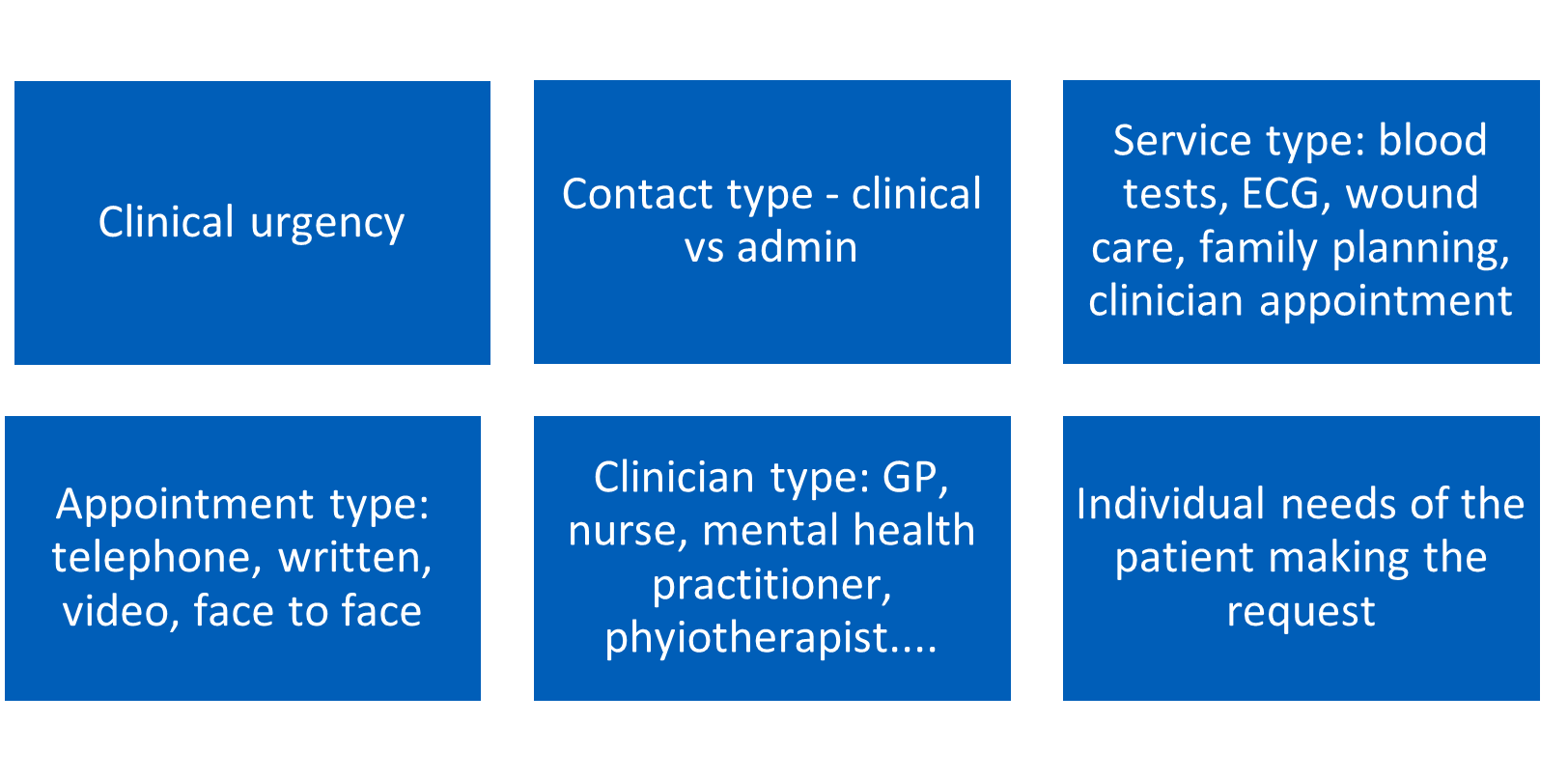

Practices must decide the best use of triage for them and their patients. Regardless of the system in place, digitally enabled triage will occur in varying degrees. Staff navigating and triaging patients have several decision points to consider (Figure 3)

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) has produced useful guidance on what good looks like for digitally enabled triage in health services. The management of OC requests can differ, as practices may:

- split requests into admin or clinical workstreams early in the process

- employ a digital care navigator/coordinator to manage all OC requests

- decentralise the management of requests and distribute requests equally amongst clinical staff

Embracing remote digital triage models

Practices planning to or currently implementing total digital triage should visit the NHS England pages on the modern general practice model and look at the digital triage calculator.

Benefits

The potential benefits of digitally enabled clinical triage are:

- increased efficiencies when implementing remote triage alongside existing models when supported by effective implementation

- ability to close consultations using written consultations directly without the need for further telephone or face-to-face contact

- earlier identification of red flag symptoms in the patient journey

- earlier redirection of patients to emergency or community services using OC tools

- increased access and early direction to self-care or self-management

- automation of booking flows where features exist as part of the OC tool

- increasing variety of access options for patients seeking care, with the removal of existing barriers for certain patient groups

- improved data-driven insights through the standardised data that digital tools can collect

- ability to direct patients to their ‘regular’ clinician earlier in their care journey

Potential pitfalls

The potential pitfalls of embracing digitally enabled remote triage are:

- potential to increase workloads if not supported by proper implementation

- increasing barriers to access for certain patient groups if not supported adequately by traditional modes of access, e.g. patients with poor access to technology or learning difficulties

- patients may find the new systems a burden or complicated to use.

- unnecessary redirection of patients to emergency services by digital tools

- increasing complexity of clinical systems that increase risks if not clearly understood

Directing patients to remote vs face-to-face consultations

Directing patients to the correct type of appointment during care navigation or triage can be difficult. The General Medical Council’s (GMC) standards of good medical practice still apply to all appointment types: online, video, telephone, and online messaging. The GMC has created a flow chart to help clinicians decide which kind of appointment they might need when triaging.

Certain presentations and patient groups will be better suited to certain types of remote consultations. For example:

- telephone consultations may suit simple problems, follow-up consultations, or discussions regarding results

- video consultation may be beneficial when visualisation of the patient aids decision-making or a remote examination is appropriate and possible within the constraints of the technology. (For example how far a finger/hand/shoulder can move, or how poorly a child looks – are they running around or in bed?)

- written consultations may only be helpful for specific conditions and when a two-way dialogue can be reliably established in a way the patient can understand the information

- using pictures or clinical images during the consultation or triage process may better suit skin conditions or help visualise problems around the eyes with more clarity

- patients with high levels of digital literacy or with English as their first language are likely to find remote consulting easier than patients who do not

- patients with increasingly complex conditions and multiple comorbidities may find remote consulting a barrier to the holistic assessment of their needs

- housebound patients may suddenly find their access to primary care has increased now they can use various remote consultation methods to interact with clinicians outside of home visits

- patients of working age may prefer remote consultation methods because they can access care without having to take time off work

The list above is not exhaustive and demonstrates the number of different factors when triaging patients remotely. The approach should be tailored to the person, the circumstance, and their needs.

Digital triage and eHubs

Primary care networks or groups of practices in a neighbourhood may decide to develop an eHub model. In this model, a centralised team receives OC requests on behalf of several practices within the network. The centralised team then processes the requests and directs patients appropriately.

The development of an eHub system allows practices to share the load of OC requests and to help take work away from practices whilst developing centralised expertise for processing online consultations.

There has been varying degrees of success with eHubs. More information can be found in the Using online consultations in primary care implementation toolkit.

Essential considerations

Practices will be using remote triage and digital triage to varying degrees. All practices should, however, review the following areas when adopting new digitally enabled triage into their systems:

- Transformation and implementation– see the Modern general practice model

- Information and clinical governance – privacy notices will need to be updated. Data impact and privacy assessments, clinical risk safety assessments, policies and protocols will all need creating, reviewing, or updating.

- Preserving working structures, capacity, and workload – triage systems heavily reliant on OC requests need to factor this into their capacity and rota planning. OC tools may need to be switched off outside of core operating hours. Vulnerable patients may be disadvantaged by remote digital triage. Developing systems and processes for staff to identify, flag and highlight vulnerable patients to the right pathway or staff member is essential

- Managing patient interactions may be challenging, and supporting staff with communication templates, scripts and guidance can be powerful

- Business continuity planning: plan for managing demand if your OC tool is broken or not working. Understand how you can control its functioning. Do you know how to turn it off if staff sickness stops or limits the processing of requests?

- Significant events and incidentsresulting from digital triage need to be reported and escalated through existing channels within the practice

Related GPG content

- Health equalities and inclusion

- Primary Care Networks (PCNs)

- Online consultation tools

- Video consultation tools

- Remote consulting tools – procurement, regulations, governance and transformation

- Remote consulting

Other helpful resources

- NHS England, Modern general practice model

- e-Learning for healthcare online course, Remote triage model in primary care

- The Health Foundation, Securing a positive health care technology legacy from COVID-19

- Health Education England, Care navigation

- NHS Digital, Digital inclusion for health and social care

- Health Education England Digital Literacy Capability Frameworks