Introduction

Postnatal and perinatal care should create a supportive environment in which women and families will be supported by professionals to make their own decisions on how to care for themselves and their baby, and to recognise and act on any concerns.

This toolkit supports integrated care boards (ICBs), their place-based partners, health and care providers to work with service users and professionals to improve the postnatal care experience and both short and long-term maternal and infant health. It shows ICB leaders what an effective, collaborative approach looks like and recommends evidence-based actions for ICBs and providers to consider taking.

ICBs, as set out in the Model ICB Blueprint, should adopt a ‘system first’ approach and act as strategic commissioners, focusing on neighbourhoods, improving population health, reducing inequalities and improving access to high-quality care. They achieve this by commissioning services that enable collaboration between providers through integrated care pathways, supported by shared resources and interoperable digital infrastructure. Providers, including maternity, neonatal, community and primary care services, play a central role in delivering postnatal care improvement. They are expected to work proactively and collaboratively across organisational boundaries and with wider system partners, such as public health, social care and the voluntary sector, to design and deliver joined-up care.

The postnatal period is defined as the first 6–8 weeks after birth and the perinatal period from the start of pregnancy up to 12 months after birth. This toolkit concerns actions to improve the care in the first 6–8 weeks but also how systems can embed these approaches across the perinatal period.

NICE guideline NG194 Postnatal care sets out the recommended universal offer for the postnatal period. Commissioners must have due regard to this universal offer when commissioning and assessing quality of postnatal care. This toolkit should strengthen how services work together to achieve its standards.

A note about language

This toolkit is inclusive of everybody who uses maternity and perinatal services. Some people do not identify with the gender that matches their sex registered at birth and our reference to women and mothers in this toolkit should be read as inclusive of all service users.

Importance of postnatal care

There is an increasing need for co-ordinated, high-quality postnatal care (the 6–8 weeks after birth. More women are experiencing complex pregnancies due to multi-morbidities and inequalities and women and families are requiring support for a broader range of physical, social and mental health issues both during pregnancy and after birth. MBRRACE reports continue to show that the rate of maternal deaths in the postnatal period is more than twice that during pregnancy. Yet, disjointed and siloed working across health and social care agencies is a repeated theme in reports, including those from MBRRACE.

This is also reflected in the greater dissatisfaction women express for postnatal care than any other aspect of maternity care; evidenced over the last 5 years through Care Quality Commission maternity experience surveys, data gathered by local maternity and neonatal voices partnerships and Healthwatch organisations, and the National Perinatal Epidemiological Unit maternity report.

Women and families with babies in neonatal care face significant challenges, including increased risks to mental health, maternal recovery and financial strain. They often report poor postnatal care experiences and that they struggle to access tailored support and information.

Developing postnatal care improvements

Postnatal care extends beyond maternity services and a collaborative, system-wide approach to postnatal care improvements is essential in delivering meaningful and lasting benefits for women and families.

As set out in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) Shared outcomes toolkit for integrated care systems, collaboration is vital to understanding population needs and providing efficient and joined-up services.

Annex B lists the range of partners ICBs are likely to want to work with to develop and implement improvements. We would expect partners to include local service users, professional groups (including GPs and health visitors), local authorities, neonatal networks and community groups.

Critically, ICBs and providers should work with their local maternity and neonatal voices partnership (MNVPs) to support meaningful engagement with service users, including women and families from seldom heard communities. Listening to and amplifying the voices of all women and families ensures services are shaped by lived experience.

Systems should also use the Perinatal Quality and Outcomes Measure (PQOM) process to drive quality improvement and reduce unwarranted variation, embedding continuous learning to strengthen safety and outcomes across maternity services. They are expected to apply an inequalities lens to their improvement work and align it with local equity and equality plans, ensuring that services deliver more inclusive, responsive and fair postnatal care to address the needs of women and families at greatest risk of poor outcomes.

Postnatal care toolkit process map

- Understand system population needs and the place-based variations within postnatal care

- Consult and engage stakeholders (service users, all professional groups, community partners)

- Map current postnatal services across all providers and community groups

- Identify system gaps and priorities across the 4 improvement domains (see below)

- Develop actions or plans for postnatal improvement (including the recommended actions below)

Postnatal care improvement domains

This toolkit recommends actions across 4 domains for ICBs, partners and providers to deliver consistent high-quality, personalised, kind and equitable postnatal care and support. These are based on good practice, findings of national and local experience surveys and the National Maternity and Neonatal Recommendations Register but do not provide an exhaustive list.

ICBs should self-assess their services against these domains and from identifying gaps formulate targeted actions or plans for sustainable improvements that place women and families at the centre of postnatal care delivery.

Critically, these domains underpin the 3 shifts essential to achieving the 10 Year Plan for Health:

- Moving care from hospital to community: This toolkit sets out how to deliver care in community settings, ensuring women and babies receive safe, personalised and joined-up care, including a choice of accessible support outside hospital environments and smooth transitions to health visiting and GP services working in partnership with women’s health and family hubs.

- Transitioning from analogue to digital systems: This toolkit emphasises the importance of using interoperable digital systems that allow care records to follow women and their families across services, reducing duplication and avoiding the need for women to repeatedly share their experiences. Maternity services will be the initial focus for the rollout of the single patient record, laying the foundation for safer, more co-ordinated and personalised care.

- Shifting the focus from sickness to prevention. This toolkit promotes a public health approach, emphasising early detection, proactive intervention and addressing the wider determinants of health. This includes targeted pathways to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality, with enhanced preventative care and support for women and families at highest risk of poor outcomes.

Domain 1: Listening to women and taking a family approach

To meet the needs of the postnatal population, ICBs must design services in collaboration with women and their families. This requires a commitment to personalised, culturally competent care and an openness to continuously improve through meaningful feedback.

Effective communication and information sharing are the foundation of seamless, well co-ordinated and holistic postnatal care. ICBs must ensure that data is collected consistently, shared efficiently and used to drive improvements in care. A robust information technology infrastructure is critical to enabling professionals to access comprehensive care records, ensuring smooth transitions and co-ordinated support across the system.

By working in partnership and leveraging these principles, ICBs can deliver supportive, responsive care that fosters better outcomes and experiences for families.

Recommended actions

1.1 Embed personalised care planning across the postnatal continuum

- Develop an integrated postnatal care pathway centred around neighbourhood care to ensure seamless co-ordination between maternity, neonatal, health visiting, primary care, local authority and voluntary sector services. It is essential to have a dedicated professional overseeing and co-ordinating every stage of a woman’s postnatal care and particularly for women and infants with multiple social and medical needs.

- Every woman should receive a personalised postnatal care plan before leaving maternity services, tailored to her clinical, psychological and social needs and giving clear guidance for managing long-term conditions and accessing specialist or community support. It should also signpost to local resources, including community and voluntary groups. A pregnancy passport could underpin this plan by recording pregnancy complications, outlining future health risks and setting out recommended follow-up to ensure consistent, co-ordinated care.

- Facilitate smooth transitions of care by involving GPs, health visitors and other relevant specialists in the planning process and ensure there are clear pathways in place for both mothers and babies after their discharge from maternity services. Maternity discharge documentation to primary and community care should be structured to make a summary of key conditions and the care plan clearly visible, with signposted detailed information about physical and mental health, medications, social complexities, further monitoring requirements or safeguarding concerns.

- Implement systems that allow care records to follow women and their families throughout their journey and eliminate any need for them to repeatedly share their experiences. Ensure that every professional involved in postnatal care has access to the up-to-date information they need to provide personalised and effective support.

- Adopt a family-centred approach that considers the broader context of the postnatal period, including the mental health and wellbeing of partners.

1.2 Provide women and families with clear and accessible information

- Equip women and families with standardised, easy-to-understand information that is tailored to their individual needs and supports the management of long-term conditions. Information should be provided in formats that overcome language and other accessibility barriers.

- Ensure that women and families are supported to make informed postnatal decisions through respectful and evidence-based discussions with professionals,

- Information should be provided in formats that overcome language and other accessibility barriers, aligning with the NHS Accessible Information Standard. When giving information about postnatal care, use language that will be understood and tailor the content and timing of delivery to the woman’s needs and preference.

- Provide women with information about what support is available, how to access these services and what to expect from them so that they can feel confident in seeking help when needed. For example, provide a local directory of service provision setting out what is available and how to contact each service.

- Provide families with information, resources and education on infant care, such as safe sleeping practices, immunisations and recognising signs of illness. Also provide tailored information on follow-up care after a baby’s discharge from neonatal services.

For guidance on communication, providing information (including in different formats and languages) and shared decision-making, see the NICE guidelines on patient experience in adult NHS services and shared decision-making, and the personalised care and support planning guidance.

1.3 Prioritise feedback mechanisms to drive continuous improvement

- Review CQC Maternity Survey data at a system level to understand the experiences of women and families using all postnatal services including health visiting and general practice.

- Develop tailored approaches to engage with underserved and seldom-heard groups, including women with babies in neonatal care, bereaved families, Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities, migrant women and those in severely disadvantaged circumstances (for example, babies taken into care and parents experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage, in prison, living with addiction or unable to care for their baby).

- Respond openly and honestly to families who have experienced adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes and actively listen to their needs. This will help rebuild the trust they may have lost in health services and encourage them to access the ongoing physical and mental health support they need.

1.4 Tailor support for families accessing neonatal services

- Develop tailored postnatal care pathways for families whose babies require neonatal care, acknowledging the unique challenges they face. They may be under significant pressure balancing family needs with frequent travel to and from the neonatal unit, making it difficult for mothers to access other services. Flexibility in service delivery should be offered to ensure the mother’s postnatal needs are met – for example, interim alternatives, such as telephone consultations, until a face-to-face contact can be arranged.

- Ensure that these families have access to emotional, psychological and practical support throughout their postnatal journey, addressing their specific needs within the wider system.

1.5 Strengthen support for bereaved parents and families

- Develop tailored postnatal pathways for families experiencing bereavement, ensuring a personalised parent-centred bereavement care plan is in place. This should provide continuity across settings and guarantee high-quality, compassionate care that reflects the family’s preferences, cultural background and individual needs. Families must be offered informed choices about decisions relating to their care. All ICBs and providers are expected to be working to the SANDS National Bereavement Care Pathway standards across all settings, as set out in the Medium Term Planning Framework.

- Ensure clear referral pathways to specialist mental health services and bereavement support are in place, and that professionals are confident in signposting families to them. In any subsequent pregnancy, trauma-informed care alongside specialist care, when needed, should be available to support parents and families in a sensitive and responsive way.

Case studies

Fit Families – Doncaster, South Yorkshire ICB

The Doncaster Maternity and Neonatal Voices Partnership identified a gap in community mental health provision and peer support for parents, in response, the ICB partnered with the charity Club Doncaster Foundation to deliver a programme of six-week ‘Fit Families’ courses.

Courses are free and cover topics that help participants work on their physical and mental health and life skills through a variety of activities, all while having their baby by their side. With an inclusive culture, the sessions support families regardless of their ethnicity, belief or sexual orientation.

Collaboration has been key. By working in partnership with a range of providers and partners – Doncaster Council and Doncaster family hubs and representatives from health visiting, midwifery, perinatal mental health, public Health, MNVP and the local maternity and neonatal system (LMNS) – Fit Families has been integrated into the statutory provision of support to postnatal communities, alongside community interventions.

The postnatal courses were initially run from a central location but now from each of the family hubs across Doncaster. With sessions already booked to capacity, further provisions will extend the ICB’s ability to reach communities further afield.

The Family Hub – Start for Life integration approach, County Durham

The Family Hub – Start for Life (SFL) programme in County Durham has strengthened integrated support for low to moderate perinatal and infant mental health (PIMH), enhancing parent–infant interactions in particular.

A PIMH referral pathway enables the family hub workforce to identify early those needing support, through health visitors, midwives, early help practitioners, GPs and neonatal units, and collaborate to provide the appropriate support. A range of low to moderate interventions, services and evidence-based therapeutic work is offered.

A specialist health visitor led multi-agency team ensures seamless referral and patient care between the specialist perinatal mental health team, talking therapies and family hubs. The specialist health visitor role has been vital in co-ordinating the delivery of the cross-sector pathway and developing multi-agency relationships.

The programme also offers multi-agency training to strengthen workforce capability. This is led by the specialist health visitor and includes reflective supervision sessions with voluntary sector partners and the specialist PMH team.

3D casting for families experiencing perinatal loss, Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust

Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust has partnered with the charity Little Cloud to provide foot cast keepsakes for families experiencing perinatal loss. Clinicians take the mould of the baby’s foot at the bedside and involved parents in this, while Little Cloud supports the filling and finishing of the casts. Little Cloud also provides oversight, training and specialist guidance to ensure the casts are of the highest quality and give staff confidence in the process.

This hybrid model maximises resources and allows the trust to embed 3D casting in the bereavement pathway in a clinically safe and sustainable way. It demonstrates how collaborating with specialist partners can maintain high standards, be adaptable to local pathways and expand access to valued bereavement services.

“Families value the results enormously and staff feel confident in the process.” Bereavement midwife, Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust

Domain 2: Addressing inequalities

As set out in the Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services, the approach to improving equity (Core20PLUS5) involves implementing enhanced midwifery continuity of carer for women from ethnic minority communities and from the most deprived areas. Systems should create targeted support where health inequalities exist in line with the principle of proportionate universalism.

They should use local data to identify disparities, develop targeted interventions and collaborate with partners and service users across the system to ensure equitable care for all women and families. The local maternity and neonatal system (LMNS) equity and equality plan should inform this work, but ICBs must also engage broader partners to address inequalities beyond maternity and neonatal services.

The Medium Term Planning Framework states the expectation that systems and services will use the forthcoming national Maternity and Neonatal Inequalities Data Dashboard to identify variation in practice and put interventions for improvement in place.

Recommended actions

2.1 Co-design service and interventions to provide equitable postnatal care

- Co-design postnatal service and care pathways with people experiencing disadvantage, including those from underserved and seldom-heard groups and ethnic minority communities, to ensure services are accessible, inclusive and meet their needs.

- Create targeted care pathways for those with protected characteristics and vulnerable groups at higher risk of postnatal maternal mortality (including suicide) and poorer long-term outcomes, including:

- refugees and asylum seekers, ensuring seamless and robust care handovers, especially where they are geographically relocated

- women whose children are placed into care, addressing their specific emotional and physical health needs

- women affected by substance misuse, with pathways that integrate specialised support and rehabilitation services as required

- women experiencing domestic or sexual violence, providing trauma-informed care

- women experiencing mental health difficulties, ensuring timely access to mental health services for assessment, support and treatment tailored to their needs

- women in contact with the justice system, recognising that those recently released from prison or serving community sentences face heightened health and social inequalities. Services must be responsive to these challenges and tailor care accordingly

- Focus on preventative care for women and families at risk of poor outcomes, offering enhanced support for the most deprived groups, such as first-time young mothers, through programmes like the Family Nurse Partnership.

2.2 Embed and co-ordinate work to tackle inequalities across the system

- Ensure organisations embed equity in their postnatal care planning and delivery, addressing inequalities linked to protected characteristics, complex social needs and inclusion health groups. Align actions with the Core20PLUS5 approach to target the most underserved groups effectively and consistently.

- Strengthen service provision to ensure women and babies receive the care they need, reducing unnecessary interactions with emergency services including the ambulance service. Regularly review data on readmissions and reattendance rates for women and babies, analysing causes and implementing targeted actions to address preventable gaps in care.

- Use women’s health hubs where possible to improve access to equitable, high-quality care for management of long-term conditions following pregnancy.

Case studies

Early Lives – Equal Start: maternity advocate community organisers, Cowley, Oxford

Equal Start Oxford (ESO), launched in 2022 by Flo’s – The Place in the Park and Oxford University Hospital, supports migrant mothers who face barriers accessing services and experience poorer outcomes.

Maternity advocates are at the heart of this initiative. These are local women who support migrant mothers to navigate healthcare and stabilise family life, and are trained to provide personalised, rights-focused support for issues like housing, immigration and domestic violence. Beyond one-to-one advocacy, ESO runs antenatal classes with translation, peer-led support addressing issues such as mental health and child development, and training in areas like first aid and interpreting.

Funded by Bucks, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West LMNS and ICB, and guided by a growing community steering group, ESO is improving access, outcomes and experiences for over 100 local families.

Newham Nurture: empowering marginalised mothers – Newham

Newham Nurture is a perinatal service to address the unique challenges faced by Newham’s most vulnerable families. The programme, delivered through a partnership with NCT, the Magpie Project and Alternatives Trust East London, supports over 600 women and babies annually, including refugees and asylum seekers living in hardship. It was co-designed with migrant and marginalised women and is guided by a steering group of mothers with lived experience, ensuring it remains relevant and impactful.

Services include bespoke ESOL antenatal education, postnatal and infant feeding support, trauma counselling, peer support and link work to advice and livelihood assistance. This holistic approach bridges gaps in healthcare access, empowers women and fosters trust by offering culturally sensitive and practical support.

Since its inception in July 2021, Newham Nurture has supported nearly 2,000 women and babies, improving their confidence and resilience. By addressing barriers to healthcare and advocating for rights, the initiative transforms lives, creating long-term positive changes for families and communities. One mother reflected: “to be in this position means I’m being listened to, and for me, it feels like I’m finally picking up all my pieces.”

Domain 3: Workforce, training and education

Skilled and compassionate professionals are critical to ensuring that women receive the physical and mental health support they need at every stage of the postnatal pathway, whether in the hospital, at home or in the community. For this, ICBs must prioritise recruitment, retention and workforce development, while fostering a culture of respect, compassion and inclusion.

Collaborative leadership and cultures that build trust and promote inclusivity across professional and organisational boundaries are essential to delivering safer, more personalised and equitable postnatal care. Embedding these in everyday practice encourages innovation, continuous improvement and meaningful engagement with all stakeholders.

Recommended actions

3.1 Develop and maintain robust workforce plans

- Ensure workforce plans resource services with appropriately skilled and trained staff who are available to meet the clinical needs of women and babies in the postnatal period, and importantly do not routinely deprioritise standard postnatal care (acute and community) during periods of operational pressure.

- Identify how staffing challenges within specific professional groups or services impact on postnatal outcomes and hold providers accountable for addressing these gaps.

3.2 Deliver targeted training and development for professionals

- Ensure all professionals providing postnatal care receive training in areas such as:

- contraception choices and safe pregnancy spacing

- pelvic health and management of long-term conditions

- infant feeding (including breastfeeding support)

- trauma-informed care and identifying where mental health support may be needed

- bereavement care, including understanding local pathways and providing sensitive, compassionate care

- social determinants of health, ensuring professionals apply a making every contact count (MECC) approach to promote healthy behaviours, signposting and addressing wider factors affecting postnatal health

- Implement additional training for GPs to support high-quality maternal 6–8-week postnatal consultations, focusing on physical recovery and mental health. Refer to GP six to eight week maternal postnatal consultation: what good looks like.

3.3 Strengthen the uptake and experience of the 6–8-week postnatal GP consultation

- Increase the uptake and quality of the GP maternal postnatal consultation by ensuring all eligible women receive a formal invitation and actively encouraging its uptake.

- Implement measures to ensure GPs are informed in cases of perinatal loss or neonatal admission, to ensure compassionate and tailored support before, during and after the consultation.

- Encourage GP practices to prioritise women at higher risk of poorer outcomes, ensuring these women attend and engage with the review process. This should be achieved through proactive, personalised support and a proportionate universalism approach, tailoring and targeting care to meet specific needs while maintaining equitable access for all women.

Case studies

Shared learning – supporting GPs with the 6–8-week postnatal consultation, NHS London Maternity Clinical Network

The London Maternity Clinical Network recognised a need to support local GPs with the new requirement in the GP contract to provide a maternal consultation at 6–8 weeks after birth in addition to the baby check.

From November 2020, a consultant obstetrician and GP maternity clinical leads have run monthly webinars at which attendees are given best practice guidance on optimising the 6–8-week maternal postnatal consultation and the opportunity to share experience and challenges.

Maternity link support workers, Birmingham and Solihull United Maternity and Newborn Partnership

Birmingham and Solihull (BSoL) ICB has a diverse population with unequal access to health services and differences in health outcomes. Evidence suggests that women from ethnic minority backgrounds and those whose first language is not English are more likely not to attend maternity appointments.

In April 2019, BSoL United Maternity and Newborn Partnership introduced a pilot scheme of maternity link support workers to provide holistic support for vulnerable pregnant women from ethnic minority backgrounds, including specialist support for social care, immigration and housing needs.

Evaluation has found that the role is highly valued, and delivery of the role is in line with key maternity transformation objectives.

Domain 4: Take a public health approach

A public health approach to postnatal care ensures that services adopt a life-course perspective for women and babies, comprehensively embedding prevention, early detection and targeted interventions that address the unique physical, mental health and social needs of individuals while tackling the wider determinants of health.

Systems need to plan postnatal pathways of care with preconception and antenatal care, focused on long-term benefits for women and babies and recognising that early interventions before and during pregnancy can improve postnatal outcomes and prevent ill-health across a woman’s life.

Recommended actions

4.1 Focus on reducing maternal morbidity and mortality

- Implement robust handover processes for women with medical conditions identified or exacerbated during pregnancy (for example, gestational diabetes, hypertension), ensuring their access to ongoing management, screening and risk reduction. In line with the Medium Term Planning Framework, implement best practice resources as they are launched, such as the Maternal care bundle and the forthcoming specification for maternity triage.

- Develop and implement system-wide care pathways that are responsive to local needs and align with the maternal medicines network service specification. Pathways should ensure appropriate postnatal follow-up and ongoing management for all women with long-term or pregnancy-related medical conditions. Systems must also ensure that, where required, a formal postnatal follow-up appointment is arranged with the relevant specialist service. This requirement, set out in the service specification, should be embedded in local pathway design to support safe and co-ordinated continuity of care.

4.2 Promote a life-course approach to postnatal care

- Integrate a partnership approach to postnatal care, providing women and families with access to health promotion information, early interventions and services that support long-term health.

- Ensure proactive referral for additional care when required, including targeted support for:

- smoking cessation, with clear pathways for relapse prevention and support for household members who smoke

- weight management to promote healthy postnatal recovery

- cervical and breast screening ensuring women are informed about the importance of screening

- promote vaccinations to both women and baby to protect long-term health

- pelvic health, providing assessment and support for postnatal recovery, with referral to perinatal pelvic health services

4.3 Support women’s choices for contraception and pregnancy spacing

- Develop integrated pathways to ensure women have timely access to the post-pregnancy contraception that meets their needs, considering both medical and social factors. Working in partnership with local authority commissioners of sexual health services ensures access across the postnatal period whether in hospital or community settings.

- Offer women choice and information around contraception and explain the risks associated with short interval pregnancies, such as preterm birth and low birthweight.

4.4 Improve infant feeding practices and parental support

- Provide all women and families with high-quality infant feeding information and support services, addressing the nutritional and emotional needs of both mother and baby.

- Facilitate multidisciplinary training across organisations to create a consistent system-wide approach to infant feeding support.

- Incorporate perinatal mental health and parent–infant relationship support in postnatal care pathways.

Case studies

Collaborative commissioning of post-pregnancy contraception services, Bristol

The Bristol Post Pregnancy Contraception Service exemplifies the power of collaborative commissioning in addressing gaps in reproductive healthcare. Recognising maternity units as accessible, trusted spaces, Bristol, North Somerset & South Gloucestershire ICB, local authorities and NHS trusts have partnered to embed contraception services within maternity care. Through shared objectives and resource alignment, commissioners have enhanced service quality and access with a holistic, patient-centred model that offers timely, convenient contraception options at a critical life stage.

The service model integrates contraceptive counselling during antenatal appointments, enabling women to make informed decisions before birth. Post-pregnancy, trained maternity staff and contraception specialists provide chosen contraceptive methods before discharge, including long-acting reversible contraception such as coils and implants. By integrating post pregnancy contraception in maternity services, women can access essential reproductive care at a time when caring for a new baby makes it difficult to engage with other healthcare services. Digital tools like patient-facing information platforms support this process and strong links with primary care ensure continuity of care.

Specialist infant feeding and nurture team, Royal United Hospitals (RUH) Bath NHS Foundation Trust

RUH Bath introduced the Specialist Infant Feeding and Nurture (SIFaN) team to address key themes identified in postnatal readmissions, particularly feeding concerns and the need for wider availability of feeding support highlighted in family and staff feedback. This multidisciplinary team includes Baby-Friendly Initiative (BFI) and International Board of Lactation Consultant trained staff and provides feeding support across acute and community settings through ward visits, maternity unit consultations and home care.

Impact measures include breastfeeding initiation rates, family satisfaction, staff input and readmission audits. 6 months into implementation, breastfeeding rates and positive family feedback regarding postnatal care have increased. However, challenges remain, particularly in supporting seldom heard families and addressing feeding complexities.

Future initiatives include deeper analysis of readmissions for feeding issues, exploration of patient self-referrals and specific training to enhance equity and equality. The team also plan to pursue BFI reaccreditation (gold standard) and launch projects to transform postnatal wards into nurturing environments, with the overarching goal of reducing health inequalities related to breastfeeding support.

Measuring impact

This section outlines considerations for ICBs in deciding what to measure to better understand the effectiveness of the current postnatal care system and monitor the impact of improvement actions. Annex C suggests metrics for measuring activity and outcomes in the postnatal period.

ICB leaders should agree and articulate the shared postnatal outcome measures for women and babies across organisations in their footprint or a place. Organisations within the ICB will already be collecting data for many metrics related to maternal and child service provision and outcomes. These should be drawn on to limit any additional data reporting burden.

Any postnatal improvement actions should draw together the different strands of organisational provision and build on the measurables that can be used across organisations.

Counts of activity, such as numbers accessing a service, only provide part of the improvement picture. Qualitative measures are also needed to understand experience of a service, such as satisfaction level or how often a woman must repeat her story, but can be more challenging to source. The 2 national sources providing patient experience feedback related to postnatal care are the Friends and Family Test and maternity CQC survey. Other sources can include local Healthwatch surveys and feedback gathered through LMNSs, MNVPs, Service User Voices or other community groups. The ICB may also want to consider surveys to gain more qualitative insights from their populations.

Using data to understand population needs and inform improvement, North West London ICB

North West London ICB recognised mother and baby attendances in emergency departments (Eds) had significantly increased over 3 years. It reviewed the Maternity Services Data Set and Emergency Care Data Set for these attendances to identify potential unmet population need. The data showed recurring themes in these attendances (including age group and ethnic group) and the ICB developed place-based solutions to avoid unnecessary ED attendances and improve health outcomes and experiences for the local population.

Annex A: The postnatal care offer

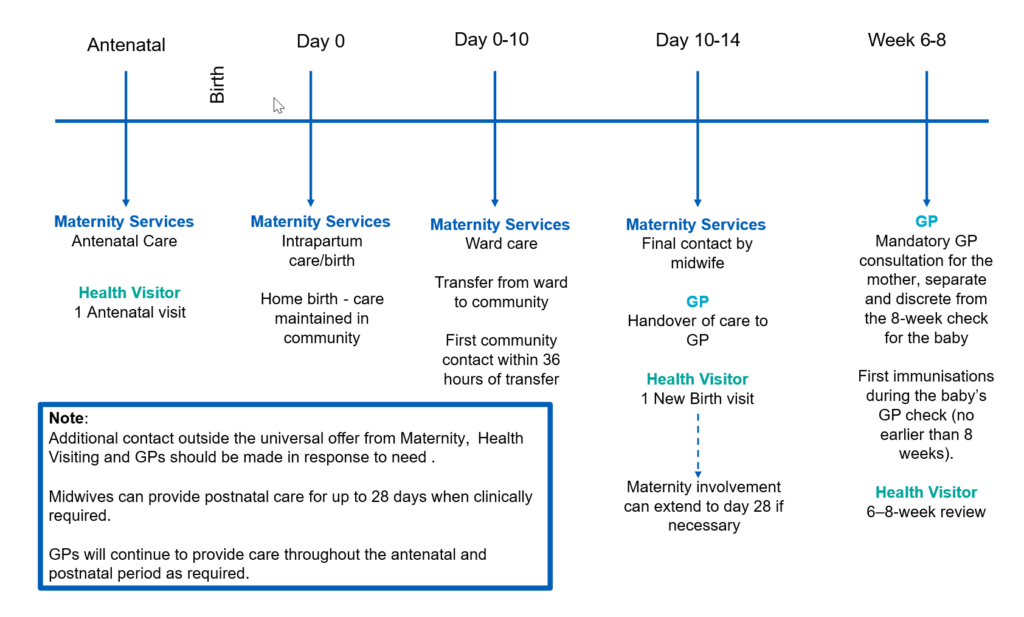

The NICE recommended universal offer presented as a horizontal timeline running from the antenatal period through to week 8 after birth can be divided into 5 key stages: antenatal, day 0, day 0–10, day 10–14 and week 6–8.

For each stage, care is provided by:

- before birth: maternity services provide antenatal care and a health visitor completes 1 antenatal visit

- on the day of birth: maternity services provide intrapartum care. For home births, care continues in the community

- between day 0 and 10: maternity services provide ward care and transfer the mother and baby to community care. The first community contact takes place within 36 hours

- between day 10 and 14: maternity services have their final contact and hand over to the GP. The health visitor carries out a new birth visit. Maternity involvement can continue up to day 28 if needed

- at weeks 6–8: the GP completes a mandatory postnatal consultation for the mother, separate from the baby’s routine check. Immunisations begin no earlier than 8 weeks. The health visitor completes the 6–8-week review.

Extra contact from maternity teams, health visitors and GPs should be based on need. Midwives can provide postnatal care for up to 28 days when clinically required and GPs will continue to provide care throughout the antenatal and postnatal period as required.

This 5-stage timeline and who provides care at each stage is shown a downloadable schematic.

Annex B: The postnatal care system

The postnatal care system involves many organisations and services but system leaders need to understand this complexity to:

- ensure care is planned and provided in a joined-up way

- clarify accountability

- assure safe and timely transfer of care between professionals and the quality of the care experience

- promote positive outcomes for service users through personalised care planning co-created with women and families

System leaders also need to understand the postnatal landscape – the needs of their local population, key partners, resources, strengths and gaps – to develop practical initiative to improve postnatal care.

They will need to map the organisations and services involved in the postnatal care system, which will depend on resources, services and the needs of the local area, and then establish who is responsible for each element of care, both within the standard offer and specialist services, and therefore for specific actions. Tools are available to assist with mapping exercises, such as RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted and informed), that will help clarify who does what in the postnatal system and who will be responsible for specific actions.

Local authorities play a vital role in postnatal care through their responsibilities for public health, including sexual and reproductive health commissioning, and addressing the wider determinants of health that significantly influence maternal and infant outcomes. ICBs should work in partnership with local authorities to ensure a joined-up approach to managing overlapping services. Collaborative efforts are essential to address inequalities, deliver preventative interventions and integrate public health priorities in postnatal pathways, ensuring that services holistically support women, babies and families within their social and environmental contexts.

Postnatal care system: stakeholder mapping

Annex C: Outcome metrics

Infant health

- Preterm birth – number of babies born <28, <32 and <37 weeks’ gestation

- Low birthweight babies – DHSC Fingertips data

- Smoking at birth – local data from tobacco dependence treatment services

- Infant feeding:

- percentage of babies receiving first feed as breast – Maternity Services Data Set (MSDS)

- percentage of babies breast fed at day 5–10 – local maternity and health visitor data

- percentage of babies totally or partially breast fed at 6–8 weeks – health visitor data

- Infant mortality:

- rate of reported still birth per 1,000 births – Office for National Statistics (ONS) births and deaths data

- rate of reported neonatal mortality per 1,000 births – ONS births and deaths data

Maternal health and wellbeing

- Percentage of women receiving a 6–8-week postnatal maternal GP consultation (SNOMED codes from NHS England GP guidance) – primary care data Number of short interval pregnancies within 12, 18 and 24 months (for caesarean births)

- Contraceptive provided:

- rate of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) prescribed by GP and sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services per 1,000 resident female population aged 15–44 years – DHSC Fingertips data

- percentage of women who chose injectable contraception at SRH services – ONS births data

- Body mass index – overweight 25 and obesity 30 or more – MSDS (at booking data)

- Women accessing perinatal mental health services – primary care, MSDS, perinatal mental health services data

- Number of women receiving a mental health assessment – MSDS, primary care data

- Number of women referred to tobacco dependency treatment services – local treatment service data

- Number of women with substance misuse identified at booking and in pregnancy – MSDS, primary care prevalence data

- Key performance indicator (KPI) for maternal medicine network (admitted through emergency department, admitted to intensive care, receive a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram)

- KPI for perinatal pelvic health service (referral rate)

- Number of women with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes, percentage of women diagnosed with diabetes within 5 years of pregnancy

- Number of women with a diagnosis of hypertension in pregnancy, percentage of women developing cardiac conditions within 5 years of pregnancy

There is variation in data collection and coding between MSDS and other sources such as Hospital Episode Statistic (HES).

Systems and organisations should work together to agree what data they will collect to measure impact and standardised ways to improve data collection and data quality within services.

Systems should be collating outcome information to inform equity, using standardised classification of ethnic groups, national identity, religion and area-based deprivation. They should also be collating data on women’s circumstances, including whether they are experiencing poverty, have migrated or sought refuge and English is not their first language.

Acknowledgments

This toolkit has been developed in partnership with service users and professional stakeholders. We would like to thank the national Postnatal Working Group members for their contribution, including the Royal College of Midwives, GPs Championing Perinatal Care, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Faculty of Public Health, the Institute of Health Visiting, the National Childbirth Trust, the London Maternal Clinical Network and the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities. We would also like to thank the organisations that contributed best practice case studies.

Publication reference number: PRN01975