Introduction

With over a million new patient referrals to specialist dermatology departments each year and around 50% of these relating to the diagnosis and management of skin lesions and skin cancer, the need to optimise referrals to ensure that the NHS system is kept as efficient as possible is key.

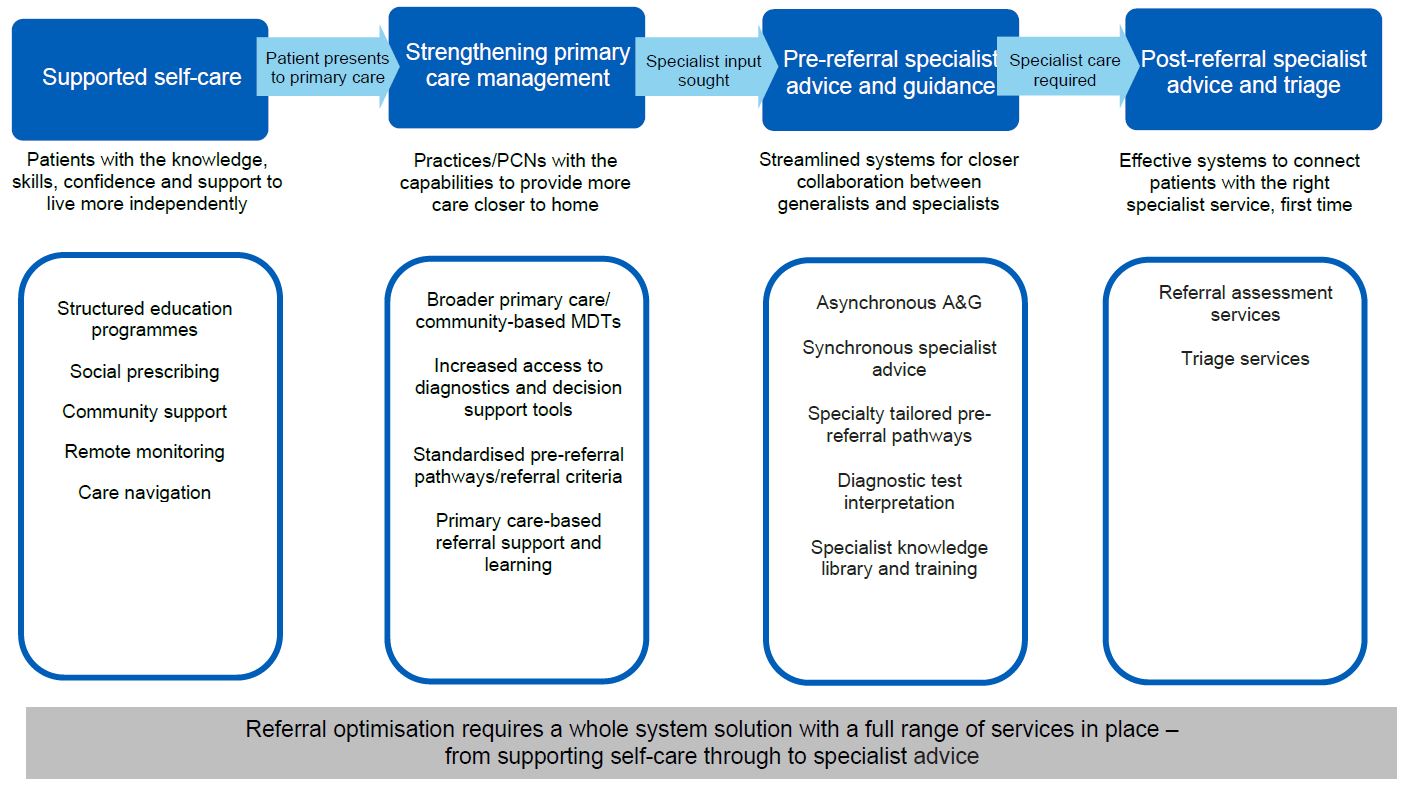

The NHS Long Term Plan recognises that the current model of outpatient delivery is outdated and the experience of outpatient visits could be improved for many patients. By improving service delivery models, it is estimated that a third of face-to-face hospital outpatient attendances could be saved by 2023/24.

To achieve this the NHS Long Term Plan commits to increasing support to primary care so that where possible hospital referrals can be avoided and patient care can be delivered closer to home. Referral optimisation is an essential component in enabling systems to support this aim.

This guidance sets out the key principles of referral optimisation for patients with skin conditions to enable local systems to embed personalised care, strengthen primary care management and streamline collaboration between generalists and specialists to ensure that patients receive the right care from the right person, the first time.

Patients with long-term skin conditions can find outpatient referral systems and processes inflexible and ineffective. The rapid access two-week wait skin cancer pathway takes priority in most specialist dermatology departments, having an inevitable impact on access for other patients.

This has led to an inequity of access to care for people with inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema, psoriasis and acne; they can wait a long time to be seen despite their condition having a significant impact on their quality of life. This guidance describes the benefits of referral optimisation including how the use of specialist advice within dermatology can help mitigate this inequity.

Specialist advice is a key initiative detailed in the delivery plan for tackling the COVID-19 backlog of elective care and 2022-23 priorities operational planning guidance. ‘Specialist advice’ is an umbrella term for a range of specialist-led models which allow the sharing of relevant clinical information either prior to referral, where the referring clinician is able to seek advice from a specialist, eg e-RS advice and guidance (A&G), telephone or e-mail services; or post-referral, where a specialist is able to review the clinical information returning the referral with guidance where appropriate or where it is necessary direct the onward referral to the most appropriate clinician, clinic and/or diagnostic pathway first time, eg e-RS referral assessment services, triage services.

The use of pre-referral specialist advice, such as e-RS A&G, followed by specialist triage is advocated as the main referral pathway for access to specialist dermatology services (with the exception of the two-week wait suspected skin cancer pathway).

This is key to improving the interface between primary, intermediate and secondary care for people with skin conditions as e-RS A&G facilitates a clinical dialogue prior to a referral being considered. Where it is advised that a referral is required, through e-RS A&G the specialist can direct the advice request (where authorised to do so by the referrer) to the most appropriate clinician, clinic and/or diagnostic pathway.

Improving the links between primary care healthcare professionals and specialists is key to ensuring patients receive care that is personalised to their needs – that is, provided by the right person, in the right place, first time.

This document was created in collaboration between the Outpatient Recovery and Transformation programme (OPRT), Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) and NHS England e-Referral Team.

It has been developed with the involvement and feedback of key stakeholders including patients, clinicians, implementation managers, relevant professional bodies such as The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD), The Primary Care Dermatology Society (PCDS), The British Dermatological Nursing Group and organisations that represent the views and interests of people with lived experience including The BAD patient group, Vitiligo Support UK, The National Eczema Society and The Psoriasis Association UK. A full list of contributors is available in Appendix 2.

Referral optimisation

Referral optimisation is the improvement of system-wide pre-referral pathways to ensure that:

- People living with long-term conditions are given the knowledge, skills, confidence and support to increasingly manage their own care and live more independently

- Primary and community services have the support they need to diagnose, treat and support more patients closer to home, without the need for onward referral

- The interface between generalist and specialist clinicians is streamlined and offers the opportunity for patients to receive optimal care at the earliest opportunity and prior to a referral into a specialist service

- Specialist clinicians have the information they need to determine the correct treatment plan, one that minimises inconvenience for patients

- Triage systems and processes are efficient: if a referral is required there are streamlined pathways that link immediately to the service that will provide the care most suited to the patient, in the right place, at the right time and using the right modality (phone, video, face-to-face).

The key principles that support a system-wide approach to referral optimisation are detailed over the following page and a summary can be found in Appendix 1.

Principle 1: Supported self-care Equipping patients with the knowledge, skills and confidence to live more independently

By:

- Ensuring consistent promotion of important public health messages • signposting reliable patient information resources and support groups

- Providing agreed written action plans (WAPs) in a format appropriate for the patientensuring access to sufficient quantities and choice of treatments • developing and promoting access to structured education programmes

- Providing details of access to emotional/psychological self-care interventions

- Developing online resources and patient-facing apps to support self-monitoring and self-care.

Around half the UK population will experience a skin condition in any 12-month period, and around two-thirds will self-care for their condition. Skin problems can have a high socioeconomic and psychological impact on affected individuals.

While many long-term inflammatory skin problems, including eczema, psoriasis and acne, are mild to moderate in severity, they still require significant levels of self-care, with topical treatments being the mainstay of this for most people. Although treatments are effective, treatment failure is common due to low adherence to topical treatments. Reasons for low adherence include:

- Confusion about treatment regimens]

- Application of topical treatments is time-consuming

- Perceived non-efficacy of treatments

- Fears over medication side effects, particularly with topical corticosteroids (TCS)

- Psychological factors.

Improving the use of core treatments, including emollients and TCS, for long-term skin conditions, is an important part of enabling self-care and improving health outcomes.

Patients with long-term inflammatory skin conditions want personalised care and interventions that improve self-care. The following elements are relevant when optimising and supporting self-care in patients with skin conditions:

Ensure consistent promotion of important public health messages

All healthcare professionals should, whenever possible, give strong evidence-based public health skin care messages. For example:

- Sun awareness advice: the link between sun exposure and skin cancer and the importance of sun avoidance and sun protection measures

- Basic advice about skin care and the importance of barrier function.

Signpost to reliable patient information resources and support groups

Consistent messages around self-care are essential and patients need to be signposted to accessible and reliable sources of information that have been awarded the Information Standard or the PIF TICK UK-wide standard for high quality information.

There are a range of resources available for people with skin conditions on the NHS website from patient support groups and professional organisations, including the British Association of Dermatologists, the Primary Care Dermatology Society (PCDS) and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP).

The British Skin Foundation provides an online Know Your Skin A-Z to help people find out about their skin condition.

Patient organisations can provide people with skin conditions with:

- Emotional and peer support – helping patients connect with others

- Information and advice – resources informed by patient experience

- Patient education – supporting evidence-based best practice

- Awareness raising – improving understanding and breaking down stigma

- Patient and public involvement opportunities, eg research and service delivery.

There is a patient support group for almost every skin condition, and these can also help people with skin conditions to increase their confidence and emotional wellbeing, and to achieve good self-care.

Provide written action plans

WAPs support patients to self-manage their skin condition. These help increase confidence with using treatments and advise patients and their carers what to do if their disease flare ups. An example is the Eczema Written Action Plan developed by the Centre for Academic Primary Care, Bristol University to support parents and carers in managing their child’s eczema.

Where this type of resource is not available it should be developed locally, in a format appropriate for the patient. Different plans will be needed for children, young people and adults.

Ensure access to sufficient quantities of treatments

People with long-term skin conditions need sufficient maintenance treatment, in particular emollients, to reduce the likelihood of a flare up. Large quantities are required on a regular basis. Suggested weekly amounts are listed in the British National Formulary (Chapter 13) and The National Eczema Society provides guidance on their use.

Prescribing restrictions for emollients were introduced in England in 2017 [13], but patients with long-term inflammatory skin conditions should still have access to their emollients on prescription [14] and in sufficient quantities. Patients should be made aware of prescription prepayment certificates, which can cut the cost of regular prescriptions and help with obtaining ongoing supplies of treatments.

Some common skin diseases, including eczema and psoriasis, may require treatment with unlicensed creams and ointments known as specials. When prescribed in the community, these treatments are often expensive and patients are referred back to dermatology solely to access them. Where possible systems should be put in place to avoid this.

Develop and promote early access to structured education programmes

Group learning sessions delivered by specialist nurse trainers give patients a better understanding of their skin condition and guidance on how to use treatments effectively and safely. An example is the Eczema Education Programme developed by Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital for children, young people and families with atopic eczema.

Signpost to emotional/psychological self-care interventions

Access to emotional and psychological support plays an important role in supporting self-care. Patients can self-refer to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), such as cognitive behavioural therapy, to help with common mental health problems, including anxiety and depression.

Psychodermatology techniques and resources, such as mindfulness and habit reversal, can also help people with long-term skin conditions and are typically used to complement other therapies. Skin Support and Atopic Skin Disease, online communities for practitioners and patients, can provide further information.

Development and use of online resources and patient-facing apps to support self-care

Online resources and patient-facing apps enable patients to monitor their symptoms on a longitudinal basis, which can empower them to access the right care pathways in a timely fashion.

An example is My Eczema Tracker developed by the University of Nottingham Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, which records patient orientated eczema measure (POEM) scores.

The Simplified Psoriasis Index (SPI), a psoriasis self-assessment tool, enables healthcare professionals or patients with psoriasis to regularly assess disease severity and its impact on wellbeing.

Emolli Zoo, from the National Eczema Society, is an app that teaches children about emollients. It includes a diary function to set up treatment reminders and enables images to be uploaded and notes to be recorded, for discussion with healthcare professionals.

The Dermatology Digital Playbook provides digital tools and case studies that clinical teams can use to support the delivery of patient pathways.

Dragon In My Skin is an online educational story aimed at children aged five to seven with eczema.

Further resources

- The RCGP Dermatology Toolkit

- Primary Care Dermatology Society

- The British Association of Dermatologists Patient Hub Skin Health

Principle 2: Strengthening primary care management

Practices/primary care networks (PCNs) with the capability to provide more care closer to home

By:

- Identifying local and regional primary care dermatology clinical champions • improving the knowledge and skills of all primary healthcare professionals, including learning from specialist dermatology nurses

- Promoting the use of readily accessible algorithms of care for common skin conditions alongside referral management guides to optimise primary care management

- Promoting and advocating the use of teledermatology to improve the primary/secondary care interface

- Establishing systems to offer clinical review of patients with long-term skin conditions

- Undertaking quality improvement (QI) activity within primary care for patients affected by skin conditions.

Skin problems are the most common reason for a new presentation in primary care (around one in four patients [15]) and most skin conditions are diagnosed and managed exclusively in primary care.

GP training in dermatology has historically been limited, and GPs often lack confidence in the use of topical treatments and are uncertain about the quantities of emollients to prescribe. This is reflected in patients’ confusion about treatment regimens and their perception that healthcare professionals under-appreciate the psychosocial impact of their skin condition.

Self-care support delivered in primary care has been observed to be low with limited written information offered or signposting to online resources.

The following elements are important in helping to strengthen the role of primary care:

Identify local and regional primary care dermatology clinical champions with the skill set to optimise the primary/secondary care interface

GPs with an extended role (GPwERs) in dermatology or dermatology champions within individual practices, local PCNs and integrated care systems (ICS) can enhance the management of skin conditions within primary care.

GPwERs in dermatology have obtained additional training and accreditation. They can support primary care by working within intermediate community dermatology services, individual practices or a PCN. GPwERs should receive mentorship and support from local specialist services. They can also support dermatology and teledermatology training locally for primary care and, as local and regional dermatology champions, can engage in local service development and improve the interface between primary and secondary care.

Where a PCN has no GPwERs, consider identifying specialist healthcare professionals from local dermatology departments to develop links with primary care clinicians, to optimise the primary/secondary care interface.

Improve the knowledge and skills of all primary healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of skin conditions to ensure consistency of message throughout the patient’s care

There are a range of opportunities to increase the dermatological skill set of health professionals working across primary care:

- Use the specialist information provided (A&G and other referral management tools) as an opportunity for education, learning and development of all primary healthcare professionals.

- Use the Health Education England Primary Care Training Hubs to provide face-to-face and online education.

- By establishing primary care practice-based dermatology meetings, local specialist services can share learning and support the development of integrated dermatology services.

- Review local A&G teledermatology cases to provide a basis for teaching and discussion.

- Develop and deliver face-to-face or virtual multiprofessional learning events for all members of the primary care team, including specialist dermatology nurses, so they can share knowledge and ensure that everyone provides a consistent and reliable message to patients.

- Invest in good clinical decision support tool templates within primary care clinical systems, to facilitate skin assessments and management reviews and to allow easy transfer of information resources to patients. Ardens provides a toolkit that allows primary care clinicians to enter information into a standardised dermatology clinical template with links to:

‒ national best practice guidance and accurate coding of clinical data to ensure that all primary care clinicians follow the same clinical guidelines

‒ high-quality patient information resources, particularly to help patients with optimal application of skin care topical treatment (as listed in supported self-care section)

‒ the patient record; this function can be seamlessly used for onward referral or A&G

‒ shared decision-making and risk communication tools to personalise care.

Promote the use of readily accessible algorithms of care for common skin conditions to optimise primary care management

Primary care practitioners should know about and have access to the range of high quality, easy to follow, pragmatic algorithms for the skin conditions they see and manage most often. Examples include:

- PCDS treatment pathways for eczema, psoriasis and acne, and concise treatment and referral guidance for common skin conditions.

- PCDS A-Z of skin conditions provides concise guidance about dermatological conditions and their management, including referral criteria and patient resources.

- The British Association of Dermatology is developing referral management guides to help clinicians optimise referrals by ensuring they are ‘specialist ready’.

- Algorithms of care and stepped management charts developed by NICE for common skin conditions.

- Consider the development and use of a locally agreed structured, standardised referral template to support dermatology A&G requests and referrals. An example is provided in the RCGP Dermatology Toolkit.

Promote and advocate the use of teledermatology to provide images to support referral optimisation and improve the primary/secondary care interface

The Teledermatology Roadmap provides guidance on the use of static digital images together with dermatology history by primary care clinicians when seeking specialist A&G, and to enable specialists to triage referrals from primary care.

The roadmap signposts to a range of resources that can support the optimal use of teledermatology in the patient pathway; others are available on the teledermatology section of the British Association of Dermatology website.

Patient information is also available on the NHS England YouTube channel.

Establish systems to offer clinical review of patients with long-term skin conditions

Systems and processes are well established in primary care to support people with long-term conditions such as asthma, cardiovascular disease and diabetes. These support personalised care by providing the opportunity for treatment reviews that aim to reduce acute exacerbations. This approach is recognised as part of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) – an annual financial reward and incentive payment made to GPs for standardised management of chronic diseases.

Although no long-term inflammatory skin conditions are included in QOF, there are many parallels with asthma, which requires self-care with treatment regimens that change as symptoms fluctuate. Developing similar models of care for people with long-term skin conditions supports personalisation of care and self-management, and also provides an opportunity for:

- Physical and psychosocial assessment, including current medication use

- Lifestyle counselling

- Preparation of WAPs

- Education around what topical treatments to use and when

- Signposting patients to resources that can help them with self-management

- Screening for joint symptoms and cardiovascular risk assessment (people with psoriasis).

This approach, while not associated with QOF, has the potential to improve patient care, support self-management and reduce referrals for specialist support.

Undertake quality improvement (QI) activity within primary care for patients affected by skin conditions

QI is an evidence-based approach to continuously improving the quality of healthcare by embedding new approaches more effectively and efficiently into practice. Many chronic inflammatory skin conditions, which require high levels of self-care and have associated co-morbidities, could benefit from a QI approach. The RCGP dermatology toolkit provides several examples and resources.

Further resources

- Primary Care Dermatology Society

- The British Dermatological Nursing Group

- The British Association of Dermatologists

Principle 3: Pre-referral specialist advice and guidance

Streamline systems for closer collaboration between generalists and specialists

By:

- Establishing integrated pre-referral specialist advice, based on services such as e-RS A&G, for all people with skin conditions

- establishing clear outcomes for the service within an agreed timeframe

- Ensuring the outcome of the specialist advice request is effectively communicated to the patient and details of the interaction are stored in the patients record

- Ensuring that good quality images can easily be attached to advice requests or transferred between healthcare professionals without encountering technical barriers such as file size

- Developing and implementing synchronous services to support immediate specialist advice where an urgent opinion is required

- Optimising the interoperability and functionality of specialist advice services, including A&G, to improve clinical efficiency

- Ensuring that patients are fully aware of what to expect from the process of pre-referral specialist advice and guidance.

Pre-referral specialist advice services can be delivered by specialists in secondary care through specialist advice services (such as e-RS A&G), or suitably trained and accredited GPwERs in dermatology working in integrated community services or virtual review services offered in primary care.

For dermatology, the use of NHS e-RS A&G is advocated as the main referral pathway for access to specialist services (with the exception of the two-week wait suspected skin cancer pathway). A&G models can be delivered by intermediate (consultant-led) and secondary care services and allow a two-way dialogue between referrer and provider.

If it is decided that a referral is required, e-RS A&G enables conversion of an A&G request into a referral where appropriate (when pre-authorised by the referrer), with a response returned to the referrer providing management information, eg if any treatment should be undertaken before the patient’s appointment.

The following guidance supports the development of these services:

Establish an integrated, system-wide A&G service for healthcare professionals caring for people with skin conditions

The development and implementation of an A&G service will require:

- Engagement with all key stakeholders in the health community, particularly primary care healthcare professionals.

- Agreement on the suitable platform(s) to deliver the service. The NHS Electronic Referral System (e-RS) has been developed for this purpose but there are also independent providers of specialist advice services. The interoperability and functionality of independently provided specialist advice services with e-RS is essential to clinical efficiency. Application programme interfaces are now available to support interoperability of e-RS A&G with hospital electronic records.

- Trusts have a legal responsibility to complete their own Equality and Health Inequalities Impact Assessment (EHIA) for the services they offer. This will help to better understand the potential positive and negative impacts of specialist advice for patients and to identify effective interventions to address potential inequalities that could emerge. Useful information can be found in the Considerations for ensuring equity of access to care when redesigning dermatology pathways document.

- Support for healthcare professionals in taking high quality images to optimise the response to advice requests.

- The facility to easily attach images to advice requests or to transfer them between healthcare professionals, without encountering technical barriers such as file size.

- Named responsibility for reviewing requests and the recommended response times (will usually be two to five working days) should be agreed between providers and commissioners and clearly documented.

- Allocation of time for review of requests by appropriate clinicians, such as specialists and GPwERs.

- Appropriate training and support to deliver the service effectively and efficiently; a team approach will ensure arrangements are in place to cover leave and sickness.

- Clearly identified links to local specialist services to ensure appropriate triage avoid any delays in the patient pathway.

- A clear understanding of the agreed outcomes.

- A system that ensures the details of the A&G request and response(s) are accessible in the patient record and that, where onward referral is required, clinical information is available to all healthcare professionals involved in the patient’s care.

- A data system to collect A&G activity to support resourcing to maintain quality and ensure that the process is optimising patient care.

Establish clear outcomes for the service with an agreed timeframe for a response

The outcomes for an A&G request should be agreed when the service is being established, including:

- Advice to the primary care healthcare professional and that to be communicated to the patient with a diagnosis, along with a suggested treatment plan to support primary care management, including guidance about when to seek further advice from the service; this may include information on low priority frameworks/treatment access policy if needed.

- Information signposting the patient to relevant patient organisations and resources.

- Educational information and links to learning resources for the referring primary care healthcare professional.

- Request for further information or images before an opinion can be provided, if required. This may include links to video clips showing patients or healthcare professionals how to take good images.

- Recommendation for onward referral, or direct conversion to referral (provided the GP has pre-authorised conversion), to either a community (GPwER-led) clinic or secondary care specialist service (see Principle 4 for triage options).

Ensure processes are in place to support communication of the outcome

- There must be a clear understanding of how the outcome of the A&G request will be shared with the patient and, where an onward referral to another service is suggested, they should be fully informed about what to expect, in what timeframe and who to contact in the event of any delays.

- It may be appropriate to share the information from the A&G interaction with the patient, in the same way they receive a documented record of a consultation with a specialist.

Ensure that images can be easily attached to A&G requests or transferred between healthcare professionals without encountering technical barriers such as file size

Wherever possible and appropriate, good digital images of skin conditions should accompany A&G requests. They are essential for reviewing skin lesions and, where possible, should be accompanied by dermoscopic images, particularly for pigmented skin lesions.

For A&G requests regarding people with pre-diagnosed inflammatory skin disease, images will enable prioritisation to a face-to-face, video or telephone consultation as appropriate, tailored to the severity and impact of the condition.

Locally developed models should be used to support the important role of teledermatology in the provision of dermatology A&G services; these could include the use of smartphone secure clinical image apps for GPs, community hubs for image taking and outreach medical illustration services.

Images taken by patients are not always of sufficient quality for specialist clinical review. Resources in the Teledermatology Roadmap and this video for patients can help.

Develop and implement synchronous specialist advice

Most specialist advice activity can be performed asynchronously, ie the communication between healthcare professionals takes place at different times over a period of hours or days. Where synchronous activity is necessary, app-based specialist advice services should be implemented, or on-call phone services should be available to allow an immediate interaction between generalist and specialist. This will facilitate urgent assessment of people with skin conditions.

Optimise the interoperability and functionality of e-RS A&G services to improve clinical efficiency

The functionality of e-RS A&G services is improving all the time, including recently the facility to convert an A&G request to a specialist referral. Where private provider systems are used for A&G, standards for ensuring interoperability are essential. Further information relating to this is in the Teledermatology Roadmap and e-RS Roadmap.

Ensuring that patients are fully aware of what to expect from the process of pre-referral specialist advice and guidance

Pre-referral specialist advice services are designed to provide information that can be used to support the shared decision-making process between referring clinicians and patients. Once the referring clinician has received advice, if they intend to refer onwards, the choices available should be discussed with the patient when agreeing the treatment plan.

If systems are using NHS e-RS A&G, this allows a service provider clinician to convert a specialist advice conversation to a referral (if authorisation has been granted by the referring clinician) and provide advice back to the referring clinician. This removes the need for the request to be returned to the referrer for them to take this action. The referring clinician should discuss possible outcomes and choice of provider with the patient before authorising the conversion to referral function on the e-RS A&G request.

Further information regarding this functionality through e-RS can be found on the NHS Digital website.

Specialist advice responses need to be both completed and communicated and discussed with patients in a timely way. In addition, staff who have contact with patients (including administrative staff) need to understand what specialist advice is and the process behind it, so they can convey this to any patients whose GP may be waiting for a response, or any patient who has an appointment scheduled to discuss advice received.

Further resources

- NHS England Teledermatology Roadmap 2020/21

- The British Association of Dermatologists Teledermatology Resources

- Elective Care Development Collaborative 100 Day Challenge

- RCGP Dermatology Toolkit

- Advice and Guidance Toolkit for the NHS E-Referral Service

- Dermatology Digital Playbook

- National Advice and Guidance Dashboard

- National Elective Care Transformation Programme’s Community of Practice SA Resource.

Principle 4: Post-referral specialist advice and triage

Effective systems to connect patients with the right specialist, first time

By:

- Linking the outcome of the pre-referral specialist advice (A&G) request, where referral is indicated, to clearly identified pathways of care provided by local services. Using effective triage, potential options might include: urgent or routine review for patient with severe skin disease; urgent or routine review for patient with suspected skin cancer; book direct for surgery with preoperative phone consultation; arrange appointment in community dermatology service.

- Ensuring referral and booking systems allow patients to see waiting times, to guide their choice of provider.

- Ensuring patients can track the booking of their appointment, and safely and easily change their appointment if needed.

Post-referral models, eg referral assessment services (RAS), provide a specialist-led assessment of a patient’s clinical referral information to support a decision on referral to the most appropriate onward clinical pathway or the return of a referral with appropriate advice to support further management within primary care.

Important note about NHS e-RS RAS

This guidance recommends the use of A&G followed by post-referral triage to the most appropriate service as the way to optimise the care pathway for people with skin conditions requiring specialist input for their management.

Local providers may set up an NHS e-RS RAS which allows referrals to be triaged before booking an appointment for the patient. If onward referral is not considered necessary, RAS also allows providers to return the triage request to the referrer with specialist advice. However, systems need to be mindful of the fact that the current e-RS RAS functionality is essentially a referral ‘accept (without advice) or reject (with advice)’ process with no opportunity for a two-way dialogue between referrer and provider.

NHS Digital provides information about RAS.

If secondary care intervention is required, the patient needs to be put on a pathway that links immediately to the service that will provide the care most suited to them in the right place, at the right time. This will involve effective and appropriate triage to the relevant intermediate or secondary care service.

As with a conventional referral to a specialist, the patient remains under the care of the primary care team until they are seen by the specialist service, even if the referral is one converted from an advice request.

Where specialist advice services are provided by independent providers there may be a lack of interoperability between these services and the NHS e-RS. Where the recommendation is onward referral, this may require primary care practices or a commissioned onward booking service to make the onward referral through NHS e-RS.

The key elements supporting referral assessment and triage are:

Link the outcome of the advice requests that require a referral to clearly identified pathways of care that are linked to local services using effective triage

Systems must be in place for appropriate and timely triage to local services. Clinicians performing triage must be familiar with all locally available services.

Systems should be developed to facilitate direct booking into local services to avoid delays, integrated with relevant electronic platforms.

The following are examples of the pathways that can be developed. These are listed in no particular order other than the first two are the most urgent:

- Direct booking for an urgent specialist dermatology review: suitable for people with severe widespread inflammatory dermatoses who are likely to require phototherapy or second-line treatments.

- Patients with skin lesions suspicious of melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma booked onto a two-week wait clinic by upgrade to a two-week wait pathway.

- Direct booking for skin surgery: the range of possible models includes direct booking to secondary care surgery lists (well suited for basal cell carcinoma) or locally accredited community/primary care surgery services with a telephone appointment to discuss surgery before the appointment.

- Routine appointments for specialist dermatology review: specialist services should operate a pooled waiting list for patients with non-specialist conditions, but take care to ensure that patients are seen by the appropriate sub-specialist (eg vulval or paediatric dermatology).

- Onward referral to a more appropriate specialist, eg plastic surgery, ophthalmology or maxillo-facial surgery.

- Booking rapid access community skin lesion assessment (‘spot’) clinics for skin lesions that are not suspicious of cancer but for which a firm diagnosis cannot be made (transforming elective care services in dermatology 2019).

- Booking appointments in a suitable community/intermediate dermatology service.

- Nurse-led clinics for patients with pre-diagnosed acne, eczema and psoriasis.

- Patients with long-term skin conditions may require redirection to a patient initiated follow-up pathway (PIFU).

Many of these interactions will be face-to-face but where appropriate a remote consultation should be considered, respecting patient choice.

Strengthen referral and booking systems to ensure that patients can see waiting times to guide their choice of provider

Systems and processes should be in place to facilitate efficient patient-centred appointment booking. Principles to enable this include:

- Tailor booking systems to the services provided to ensure triage is enacted appropriately; personalisation of the triage options is likely to require more complex non-centralised booking systems.

- Optimise the interoperability and functionality of referral services and referral triage to improve clinical efficiency, including by allowing image attachments, transfer and viewing.

- For onward referral pathways, ensure clinical information is available to all healthcare professionals involved in the patient’s care and that any relevant investigations are arranged when necessary.

- Maintain a dynamic Provider Directory of Services (DoS) with clearly identified pathways of care that are linked to local services and national referral guidelines.

- All dermatology services regardless of provider and sector should be listed and accessible on the DoS.

- Flexible systems that can modify capacity of services to meet the needs of patients with suspected skin cancer and those with acute and long-term inflammatory conditions.

Ensure patients can track the booking of their appointment, as well as safely and easily change their appointment if needed

Make sure that patients who are not digitally enabled are not disadvantaged in any way, as with any pathway redesign.

Further resources

- The British Association of Dermatologists eReferral Service in Teledermatology

- NHS Digital e-Referral Service Support for Professionals in Response to Covid.

Principle 5: Monitoring and evaluation of specialist advice services advice and triage

Highlight good practice, support benchmarking and inform opportunities for system improvement

By:

- Analysis of utilisation and outcome data through system EROC

- Review and analysis of specialist advice services.

Measuring and evaluating specialist advice services can highlight good practice, support benchmarking and inform opportunities for system improvement. This helps develop sustainable services and ultimately improves outcomes for patients. Consequently, specialist advice services should be regularly reviewed to ensure they meet local requirements and quality standards.

The System Elective Recovery Outpatients Collection (EROC) is a data collection intended to support assurance of elective recovery in line with the 2022/23 priorities and operational planning guidance and allows systems to establish a rich flow of information that can be used as a system improvement tool. The System EROC includes any interactions that facilitate the seeking and/or provision of specialist advice. This can be through specialist advice sought before or instead of a referral, or through triage or RAS services that provide specialist advice post referral but pre booking.

More information on System EROC and FAQs can be found on the System EROC page on the FutureNHS Outpatient Recovery and Transformation platform.

A System EROC dashboard has been created to support systems with monitoring and evaluation of specialist advice services which have been submitted to the collection, this can be accessed here:

System Elective Recovery Outpatient Collection Dashboard: Views – Tableau Server

A registered OKTA account is required to access the dashboard, register here: NHS England » NHS England applications

As well as analysis of utilisation and outcome data through system EROC, review and evaluation of specialist advice services should also include:

- Periodic, internal qualitative review/audit of specialist advice responses by provider organisation to ensure clinicians across the team are giving consistent and comprehensive advice

- Review and reporting of high volume and/or repeated specialist advice requests with incomplete clinical information or those for which advice is readily available from accessible and recognised national referral resources

- User satisfaction (with outcomes) and experience (of process) – for both requesting clinicians and responding clinicians

- Patient feedback.

Data should be available at a local level through the specialist advice platform being used in the service, and there are also various e-RS data and extracts for any services using specialist advice through the e-RS Advice and Guidance function (which can be found in the NHS Digital Advice and guidance toolkit).

References

- Schofield J, Grindlay D, Williams H. Skin conditions in the UK: a health care needs assessment. Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, University of Nottingham; 2009.

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Skin. The psychological and social impact of skin diseases on people’s lives, 2013.

- Devaux S, Castela A, Archier E, Gallini A, Joly P, Misery L, et al. Adherence to topical treatment in psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012; 26 Suppl 3: 61-7.

- Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, Serup J. A prospective study of patient adherence to topical treatments: 95% of patients underdose. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59(6): 975-80.

- Sokolova A, Smith SD. Factors contributing to poor treatment outcomes in childhood atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol 2015; 56(4): 252-7.

- Santer M, Burgess H, Yardley L, Ersser S, Lewis-Jones S, Muller I, et al. Experiences of carers managing childhood eczema and their views on its treatment: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2012; 62(597): e261-e7.

- Ring L, Kettis-Lindblad A, Kjellgren KI, Kindell Y, Maroti M, Serup J. Living with skin diseases and topical treatment: patients’ and providers’ perspectives and priorities. J Dermatol Treat 2007; 18(4): 209-18.

- Powell K, Le Roux E, Banks J, Ridd MJ. GP and parent dissonance about the assessment and treatment of childhood eczema in primary care: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018; 8(2): e019633.

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 55(4): 607-13.

- Thorneloe RJ, Griffiths CEM, Emsley R, Ashcroft DM. Intentional and unintentional medication non-adherence in psoriasis: the role of patients medication beliefs and habit strength. J Invest Dermatol 2018; 138(4): 785-94.

- Thorneloe RJ, Bundy C, Griggiths CEM, Ashcroft DM, Cordingley L. Adherence to medication in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168(1): 20-31.

- Nelson PA, Barker Z, Griffiths CE, Cordingley L, Chew-Graham CA. ‘On the surface’: a qualitative study of GPs’ and patients’ perspectives on psoriasis. BMC Fam Pract 2013; 14: 158.

- NHS England. Conditions for which over the counter items should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: Guidance for CCGs, 2018.

- NHS England response to concerns raised about emollient rationing by CCGs.

28 | Referral optimisation for people with skin conditions - Schofield JK, Fleming D, Grindlay D, Williams H. Skin conditions are the commonest new reason people present to general practitioners in England and Wales. Br J Dermatol 2011; 165(5): 1044-50.

- Yaakub A, Cohen S, Singh M, Goulding J. Dermatological content of UK undergraduate curricula: where are we now? Br J Dermatol 2017; 176(3): 836.

- Le Roux E, Powell K, Banks JP, Ridd MJ. GPs’ experiences of diagnosing and managing childhood eczema: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68(667): e73-e80.

- Lambrechts L, Gilissen L, Morren MA. Topical corticosteroid phobia among healthcare professionals using the TOPICOP score. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99(11): 1004-8.

- Nelson PA, Chew-Graham CA, Griffiths CE, Cordingley L. Recognition of need in health care consultations: a qualitative study of people with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2013; 168(2): 354-61.

- Le Roux E, Edwards PJ, Sanderson E, Barnes RK, Ridd MJ. The content and conduct of GP consultations for dermatology problems: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract 2020: bjgp20X712577.

Appendix 1: Generic and specialist approach to referral optimisation

A system-wide approach to referral optimisation for people with skin conditions

Supported self-care: Patients with knowledge, skills, and confidence to live more independently

- Ensure consistent promotion of important public health messages

- Signpost reliable patient information resources and support groups

- Provide agreed written action plans (WAPs)

- Ensure access to sufficient quantities of treatments

- Develop and promote access to structured education programmes

- Provide details of access to emotional/psychological self-care interventions

- Support the development and use of online resources and patient-facing apps to support self-monitoring and self-care.

Strengthening primary care management: Practices/PCNs with the capabilities to provide more care closer to home

- Identify local and regional primary care dermatology clinical champions

- Improve the knowledge and skills of all primary healthcare professionals

- Invest in good decision support tool templates within primary care clinical systems

- Promote the use of readily accessible algorithms of care for common skin conditions alongside referral management guides to optimise primary care management

- Promote and advocate the use of teledermatology to improve the primary/secondary care interface

- Establish systems to offer clinical review of patients with long-term skin conditions

- Undertake quality improvement (QI) activity within primary care for patients with skin conditions.

Pre-referral specialist advice and guidance (A&G): Streamlined systems for closer collaboration between generalists and specialists

- Establish integrated pre-referral specialist advice, based on services such as e-RS A&G, for all people with skin conditions

- Establish clear outcomes for the service with an agreed timeframe

- Ensure the outcome of the specialist advice request is effectively communicated to the patient, and details of the interaction are stored in the patient’s record

- Ensure good images can easily be attached to advice requests or transferred between healthcare professionals without encountering technical barriers such as file size

- Develop and implement synchronous services to support immediate specialist advice where an urgent opinion is required

- Optimise the interoperability and functionality of specialist advice services, including A&G services to improve clinical efficiency

Post-referral specialist advice and triage: Effective systems to connect patients with the right specialist, first time

- Link the outcome of the pre-referral specialist advice (A&G) request, where referral is indicated, to clearly identified pathways of care provided by local services. Using effective triage, potential options might include:

- urgent or routine review for patient with severe skin disease

- urgent or routine review for patient with suspected skin cancer

- book direct for surgery with preoperative phone consultation

- arrange appointment in community dermatology service

- Ensure referral and booking systems allow patients to see waiting times to guide their choice of provider

- Ensure patients can track the booking of their appointment, and safely and easily change their appointment if needed.

Appendix 2: List of Contributors

NHS England would like to thank the following for their contribution to the development of this guidance.

- British Association of Dermatologists: Dr Tanya Bleiker. Tania Von Hospenthal.

- British Association of Dermatologists Teledermatology Committee, NHS England e-Referrals Secondary Care Team: Dr Carolyn Charman.

- Patient representatives and organisations: Amanda Roberts – The BAD patient group. Emma Rush – The BAD patient group and Vitiligo Support UK. Andy Proctor – National Eczema Society. Helen McAteer – Psoriasis Association UK.

- Primary Care Dermatology Society. Dr Angelika Razzaque to 30 June then Dr Timothy Cunliffe. Dr Naomi Kemp

- British Dermatological Nursing Group: Rebecca Penzer-Hick (Chair BDNG).

- Getting It Right First Time: Dr Nick Levell – Dermatology Clinical Lead

- NHS England Outpatient Recovery and Transformation Clinical Leads: Dr Julia Schofield. Dr Emma Le Roux.

Publication reference: PR1149