1. Community health services cover a diverse range of healthcare delivery. This publication supports improved commissioning and delivery of community health services. Codifying community health services will help to better assess demand and capacity. It will also help commissioners make investment choices as they design neighbourhood health provision that shifts care to community-based settings.

2. For the first time we are publishing an overview of the core community health services that integrated care boards (ICBs), service providers and their partners should consider when planning services for their local population.

3. This publication is available for designing, commissioning and delivering community health services, including neighbourhood health. ICBs and their partners should consider the core components to:

- support demand and capacity assessment and planning with providers

- ensure the best use of funding to meet local needs and priorities

4. We describe the core components of NHS ICB-funded community health services for children, young people and adults across England. ICBs and their local authority partners will need to adapt and develop the core components according to local need. This tailored approach will help achieve the government missions of increased illness prevention and supporting more patients in the community instead of in hospital. ICBs and providers already have considerable freedom to be innovative and flexible when delivering services, and this should continue.

5. Community health service providers typically cover specialist support for people with physical health needs and neurodevelopmental services for children. Community mental health provision is typically delivered by mental health provider organisations that work closely with community health services. The scope of these services is not included in this publication.

6. Everyone will use community health services during their lives. They support newborns in their earliest days and provide advice and specialist care throughout childhood, such as speech and language therapy. In adulthood, they are there when we need specialist support throughout working age, such as musculoskeletal services. As we age and when we approach the end of life, community health services also help us stay independent and supported at home. See Annex 1 for lived experience examples of patients supported by community health services.

7. Often working in a variety of settings – such as our homes, schools, GP practices, care homes and hospitals – patients often get to know individual services well, but the full range of community health services is less widely understood by the population. Due to the complexity of need, services are often provided at home that otherwise would have been provided in general practice or another healthcare setting.

8. Timely and effective community health services working with other health and social care providers can prevent ill health, reduce health inequalities, reduce exacerbations of ill health and help keep people supported at home rather than in hospital.

9. Using the same name, definition and categorisation of community health services across England will help to measure demand, capacity, service activity and workforce more clearly and consistently. It will also help us demonstrate the important impact of community health services for patients and integrated care systems and reduce unnecessary variation in provision.

10. Community health services are delivered by a range of professions and are organised in many ways depending on the structure of the integrated care systems. This publication focuses on the core service provision that should be considered for every neighbourhood. It does not cover the organisational form or operating models for community health services.

11. Community health services play a key role in neighbourhood health services. The community health services workforce are often members of multidisciplinary teams that support people with complex needs, such as people who are housebound, those experiencing homelessness, drug and alcohol dependant, requiring mental health support, people living with cancer and unpaid carers. Some community service providers are commissioned to provide integration and coordinating functions across providers.

12. As set out in the NHS Community Health Services Data Plan 2024/25 to 2026/27, data should be based on clear and consistent measures and service definitions to understand and compare what is happening in community health services across the country. Without a degree of standardisation, unwarranted variation and inequalities cannot be identified reliably, making it difficult to deliver equitable patient care and value for money for the public.

13. Over the coming years, we will continue to work with ICBs and community service providers to:

- align and develop community health services activity, workforce, and financial data with this publication’s categorisation of services

- develop the federated data platform to collect the right community health services data, with definitions and associated performance to align with this publication’s categorisation of community services (until this is developed, there is no requirement to change data reporting in the short term)

- develop tools to support consistent analysis of community health services demand and capacity

- use the updated data set to develop more specific productivity measures and costing information for community health services

- ensure that community health services data is captured in a modernised and appropriate electronic patient record

- access digital tools to enable the workforce to spend more time with patients

- retain and develop the community health workforce

- develop service specifications where there is a clear need for this to be done nationally

- develop benchmarking tools to support service improvement

- continue to update this publication as we learn more.

14. ICBs should ensure that the implementation of the core components aligns with the implementation of related policy and guidance locally (see Annex 2). The following organising principles and policy areas are central to this:

- equitable and accessible services, based on population need

- timely identification of need and follow-up action

- personalised care

Community health service providers

15. Community health services are provided by over 800 different organisations, including NHS bodies, local authorities, for-profit and not-for-profit providers such as voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE), community interest companies and independent providers.

16. There are a variety of referral routes into community health services, including self-referral. Primary care and hospital trusts are the largest referrers, with each referring a similar number of cases each year to community health services. Care contacts per year are similar to the total number of hospital trust outpatient attendances.

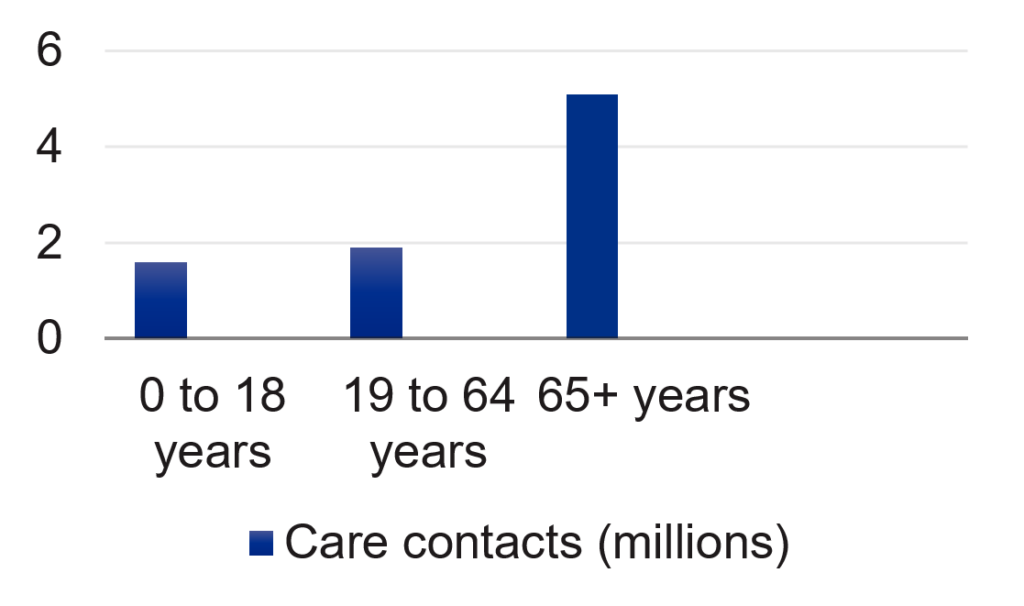

Figure 1. Care contacts a month

Care contacts in community health services broken down by age, based on 2024 data

17. As Figure 1 shows, there are about 1.6 million care contacts per month for people aged 0 to 18 years, 1.9 million for people aged 19 to 64 and 5.1 million for people aged over 65. For all ages, there are over 100 million care contact per year.

Community health service workforce

18. The community health services workforce accounts for about a fifth of the workforce in NHS trusts. The workforce includes:

- registered community nurses

- specialist nurses

- advanced practitioners

- allied health professionals, such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, dieticians and podiatrists

- consultant doctors

- consultant nurses

- a significant range of un-registered staff roles

19. Professionals in community health services support people with episodic needs, with an increasing number of services available for people to self-refer to. They also support people manage long-term conditions, often providing highly specialist services to enable people with complex needs to live at home.

20. Increasingly professionals in the community work as part of multiprofessional teams to support the most complex patient groups to manage their health needs in the community (for example, frail elderly, palliative and end of life care patients, and children with complex needs). These teams also work together to manage people’s worsening health conditions in the community wherever possible, supporting patients’ care and wellbeing. However, the extent of multiprofessional working for complex patient groups varies across the country.

21. Staff also work within urgent care services such as urgent community response (UCR), virtual wards and rehabilitation services in the community to support patients with escalating health needs or on discharge from hospital. In many places these are relatively new services.

Community health service funding

22. The funding and commissioning of community health services is complex. In 2023/24, ICBs allocated £12.3 billion of annual NHS funding to community health services. Some community health services, such as health visiting and school nursing, are funded through local authorities. Some ICBs work closely with local authority partners to pool funding and jointly commission some community health services, particularly when people have a combination of health and social care needs. This includes funding intermediate care through the Better Care Fund and other local joint funding arrangements.

23. Some organisations who are commissioned to provide NHS services via ICBs also receive a significant proportion of funding through charitable fundraising, such as those providing palliative care and end of life care services.

24. Some services such as neurodevelopmental assessment are provided by community services in some areas and by mental health services in others. Where provided by community services, this should continue.

Core components of community health services

25. The tables below list the NHS ICB funded core components of community health services and should not be seen as an exhaustive list.

Table 1: Adults community health services

Core components of community health services, led by adult community (including district) nursing, specialist nursing, allied health professions or community medical generalist.

| Care type | Category | Description | Core components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planned care – targeted and specialist services via professional or self-referral. | Episodic/specialist care | Services addressing specific or irregular health issues. | – community musculoskeletal (MSK) services – podiatry – audiology – phlebotomy – community – dentistry |

| Planned care | Management of long-term conditions | Often highly specialist services to enable people to live at home with severe disease. | – continence, bladder and bowel – respiratory – diabetes – tissue viability and wound care – lymphoedema – heart failure – home oxygen – cardiology – neurological conditions – transition from Children and Young People services |

| Planned care | Prevention of deterioration of long-term conditions | Services focused on preventing health issues from worsening. | – occupational therapy – nutrition and dietetics – residential and nursing home in-reach – speech and language therapy – physiotherapy – falls and fracture prevention – community nursing |

| Planned care | Community rehabilitation | Therapy-led to support people to recover and retain function, specialist pathways. | – neurology, pulmonary, stroke, cardiac rehab (longer-term pathways) – inpatient ward rehabilitation – equipment – wheelchair services – orthotics and prosthetics musculoskeletal (MSK) therapies services – falls and fracture prevention |

| Planned care | Palliative care and end of life care | Care outlined within statutory guidance, service specifications and the Ambitions framework. Specialist palliative care (alongside generalist palliative and end of life care), also has a role in the management of long terms conditions and in preventing their deterioration. | |

| Planned care | Neurodevelopmental | To enable those with neurodevelopmental conditions to receive assessment and diagnosis (where not provided through mental health pathways), and those with a learning disability to receive targeted and specialist support to stay well. | – community learning disability teams – access to specialist functions specifically developed for people with a learning disability, including, not limited to: occupational therapy; speech and language; nutrition and dietetics; epilepsy care – neurodevelopmental assessment |

| Planned and Reactive care | Intermediate care | Therapy-led support for people to recover and retain function, as well as specialist pathways. | – intermediate care – home and community bed based – discharge facilitation – discharge home to assess |

| Reactive care – services that respond to a sudden clinical need at home or as part of early discharge or step-down care following an hospital stay. | Urgent care | Provision of acute clinical service at home or sub-acute care in a community bed, which may require a more rapid response than can be delivered by other services. For some patients, access may be via a single point of access (SPoA). | – urgent community response / rapid response – virtual wards (also known as hospital at home) – community dentistry |

| Reactive care | Palliative care and end of life care | Including 24/7 access to advice for professionals. | |

Table 2 – Children and young people’s (CYP) community health services

Core components of community health services, led by children’s community nursing, specialist nursing, allied health professions, community paediatrician.

| Care type | Category | Description | Core components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planned care – targeted and specialist services via professional or self-referral. | Developmental | To enable children to achieve their maximum potential, for example with neurodevelopmental conditions. | – occupational therapy – physiotherapy – speech and language – paediatric ophthalmology – community paediatrics and child development centres, including: neurodevelopmental assessment; neuro-disability assessment – audiology – nutrition and dietetics – equipment wheelchair services – orthotics and prosthetics |

| Planned care | Children’s specialist services, including management of long-term conditions | Often highly specialist services to enable people to live at home with severe disease. | – continuing care – safeguarding – children in care – SEND, including education, health and care statutory services and support throughout transition and preparing for adulthood – special school nursing – respiratory – continence, bladder and bowel – tissue viability diabetes epilepsy – long term ventilation community dentistry – musculoskeletal (MSK) therapies services – phlebotomy |

| Planned care | Palliative care and end of life care | Care outlined within statutory guidance, service specifications and the Ambitions framework. Specialist palliative care (alongside generalist palliative and end of life care), also has a role in the management of long terms conditions and in preventing their deterioration. | |

| Reactive care – services that respond to a sudden clinical need at home or as part of early discharge or step-down care following an hospital stay. | Urgent care | Provision of acute clinical service at home which may require rapid response than can be delivered by other services. For some patients, access may be via a single point of access (SPoA). | – rapid response teams – virtual wards (also known as hospital at home) |

| Reactive care | Palliative care and end of life care | Including 24/7 access to advice for professionals. | |

Next steps for integrated care boards

26. ICBs should use this publication when designing and commissioning neighbourhood health locally. They should also give due regard to patient flows across providers and at a neighbourhood level.

27. ICBs should work with local authorities, providers and partners to understand demand and capacity for community health services to help determine the future opportunity for community health services to work in partnership with other providers to improve outcomes, patient experience and support the shift of activity from hospital to community.

Annex 1 – Lived experience of community health services (CHS)

Caroline has young children with complex needs: “It is absolutely the truth that without CHS my children’s quality of life would be significantly impacted. It’s not just the impact on my sons’ lives, but the people around them, school, friends, family.”

Dave and Lisa care for their son, who has profound and multiple learning disabilities and complex health needs, at home. “Community services provide continuous care and support. Community nurses undertake regular blood tests, and the local epilepsy nurse trains our son’s personal assistants to administer emergency medication. Following complications from surgery, the community team stepped in to support the Hospital at Home service and to establish a whole multidisciplinary team. Tasks included maintaining a drip to provide fluids and monitoring vital signs and weight during recovery period. We simply would not be able to care for our son at home without the care and support of community services.”

When Stephen first came out of hospital many years ago, he felt that: “we didn’t know how to make it work; we just accepted what was offered and fitted around what the services could provide. My needs have stayed the same; however they are now much better met. The responsiveness of delegating tasks has allowed me to be more flexible in living my life, to the extent that has been lifesaving. Now I feel like I have a life worth living.”

Tina spoke about integrated care and the profound impact this had: “I made the transition from 24/7 care to community care with a package of care, supported by my friends and family. My GP and the whole community team worked together with me to develop a care package. My transition into community services also opened access to wider support in the community through a range of groups and organisations.”

Claire spoke on behalf of her family: “The staff who answered our numerous phone calls as the first point of call, the district nurses and home care day and night staff all helped to make the journey towards mum’s end of life, somehow more bearable. We have been treated just as we would have hoped to be at our most distressed and mum’s most vulnerable. From the first time we made contact and spoke with the kind and caring staff who answer the phones, we have felt confidence from the outset that mum, and our 90 year old dad, would be cared for as we would have chosen.”

Ahmed, an 80-year-old recently widowed man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Parkinson’s disease had a fall at home. A specialist paramedic visited and assessed him at home. Ahmed was found to be at high risk of needing hospital admission, and therefore admitted to the virtual ward. On the virtual ward, he received hospital-level interventions, including blood and sputum tests, a chest x-ray and ECG. He improved with treatment and was discharged from the virtual ward after 7 days, and he was referred for ongoing care with the community therapy team. This collaborative approach across community services enabled the patient to remain in his own home, avoiding admission to hospital, which was especially important to him given his recent bereavement.

Fred was an 80-year-old widowed man brought by ambulance to A&E department with acute heart failure. He needed acute admission but having been assessed by the frailty front door team was admitted directly to the Integrated Frailty Unit. His daughter commented that suddenly he was in a place where not only was there an assessment of his physical health but that “got him” as a human being. The frailty specialist met Fred in hospital and also followed him up at home. Central to Fred’s care was always what was important to him (which was being at home). The frailty specialist remained the coordinator of all of the services for Fred both within the hospital and when he was discharged. Central to this coordination was the multidisciplinary team approach both through his acute care and at home care planning his proactive care.

This was best captured by Fred’s daughter: “There were so many different teams involved, and all played a part in increasing my dad’s health, independence, mobility and wellbeing. There has been the most incredible orchestra around my dad and the conductors of the orchestra have been the frailty specialists.”

Annex 2 – Other relevant guidance

The following national policy and guidance are also highlighted for consideration:

- Community health services data plan

- Integrated care system intelligence functions guidance

- Intermediate care framework

- Proactive care framework

- Providing proactive care for people living in care homes – Enhanced health in care homes framework

- Community MSK improvement framework

- Community rehabilitation and reablement model

- Adult autism strategy: supporting its use

- Meeting the needs of autistic adults in mental health services

- Public heath grant

- Healthy child programme

- Single point of access guidance

- National Framework for NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS-funded Nursing Care

- National Framework for Children and Young People’s Continuing Care

- Palliative and end of life care: Statutory guidance for integrated care boards

- Personal health budgets guidance

- Virtual wards guidance

- Urgent community response guidance

- Safer staffing tool for district nursing

- NHS Impact

- Futureproofing Community Children’s Nursing

- Transition from child to adult health services for people with complex learning disabilities

Case study: standardising community health services to address variation and improve outcomes

This case study describes how North Central London Integrated Care System developed a core community services offer as part of a 5-year implementation plan to address variation in community health service provision and improve outcomes.

Publication reference: PRN01619