HeHealth and care needs are changing. People are living longer with more long-term conditions such as asthma, diabetes, and heart disease. Population health is one of the core strategic aims for integrated care systems (ICSs). It is an approach aimed at improving the health of an entire population. It is about improving the physical and mental health and wellbeing of people, whilst reducing health inequalities within and across a defined population.

What is population health management?

Population health management (PHM) improves population health through data-driven planning and the delivery of proactive care to optimise health outcomes. It is essentially about:

- moving from a largely reactive system (that is responding when someone becomes unwell)

- moving to a much more proactive system (that is focusing on interventions to prevent illness, reduce the risk of hospitalisation, and address inequalities across England in the provision of healthcare)

Historically, health and care systems have categorised populations by the service they use at a point in time. For example, people accessing care from their GP are delivered a different ‘bundle’ of services to those receiving acute inpatient care. This can lead to inconsistent, fragmented, episodic care which is not always delivered in the most appropriate setting.

PHM is a partnership approach across the NHS and other public services including local authorities, emergency services, schools, the voluntary sector, housing associations, social services, patient groups, communities, and the public. All have a role to play in addressing the interdependent issues that affect people’s health and wellbeing.

PHM uses data, both healthcare data from clinical systems and non-healthcare data from sources including local authority and social services. The data from the non-healthcare data bucket can include information regarding lifestyle, housing, and deprivation data.

Factors in health inequalities

Health inequalities are analysed and addressed across four factors:

- social deprivation, including income

- geography, e.g., region or whether urban or rural

- specific characteristics, such as gender, ethnicity, or disability

- socially excluded groups, for example people experiencing homelessness

By safely and securely collecting and analysing data, population groups can be identified and the needs of those groups and individuals can be anticipated.

Inequalities in health, related to social deprivation can include:

- adverse effects on many aspects of health, including life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, infant mortality, cancer and chronic disease outcomes, and pregnancy complications

- worse rates of adverse health factors such as smoking, obesity, poor nutrition, and drug misuse

- reduced access to services such as education and care

Linked data sets are particularly powerful in supporting proactive, person-centered care. The aim is to enable services to act as early as possible to keep people well, targeting support where it will have the greatest impact.

Primary care teams have a unique understanding of the needs of the communities they serve, and PHM approaches seek to build on this insight. By having standardised data sets and using data systematically, PHM can support integrated care systems, primary care networks (PCNs) and, in turn, general practice, to understand the needs of the network’s whole population. This includes:

- understanding any local health inequalities which may be due to geography, deprivation, industry, or other non-health related factors (bearing in mind that health only influences a small proportion of an individual’s health and wellbeing)

- targeting support where it will have the greatest impact (often using tools such as segmentation and stratification)

Segmentation

Understanding population need is fundamental to service planning but can be daunting when faced with populations of millions of people.

Segmentation is one tool to support improved understanding of population need by dividing the population into more manageable chunks or segments, where each segment has relatively similar healthcare needs and priorities:

- the set of population segments must be limited to a manageable number if the healthcare system is to offer a sensible array of integrated services for each segment

- the set of population segments should be broad enough to include everyone, that is, at every point in their life, every person should fit into one of these categories, and there should be no individuals who do not fit into a segment

- the people in each population segment must have similar health care needs, but each segment must be different enough to justify separate consideration, for example under 5s, and over 80s, are groups which have very specific and different needs

By planning and delivering care that responds to the needs of different segments, and by integrated working, the endeavour is to optimise patient outcomes, improve patients’ experiences of services, and reduce costs per patient.

Data from the National Commissioning Data Repository has been transformed into a person-centred segmentation dataset (or data model) that can be used to derive segment-specific insights. It includes secondary care, emergency care, community services and specialised services’ datasets for the entire population.

ICSs are also developing their own locally tailored analytics functions and linked data to support this process.

Uses of segmentation

Segmentation can be used, as part of a broader PHM strategy to:

- improve coordination of care at a local, regional, and national level (PCNs & ICSs)

- improve and provide more care using the same overall resources (shared resources across PCNs)

- understand drivers of demand more accurately, using these to forecast and plan for such changes

- move to a more nuanced, targeted, and focused delivery of care built around the different needs of specific cohorts (such as cardiovascular disease risk)

- answer complex analytical and research questions about the link between care provided and resulting outcomes

- view system transformation programmes through a person-centred (segment specific) lens, baselining, tracking, and monitoring changes following interventions or service redesign for specific cohorts (through, for example, the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)

Stratification

There are three stages of risk stratification:

- targeting | choose and quantify the cohort of patients at risk of poorer health outcomes (e.g. potentially preventable hospitalisations) that are considered a priority for targeting with different or additional interventions, this can be at practice, network, or ICS levels

- identification | identify individuals within the target cohort, through manual or automated searches of routinely collected clinical and demographic data held in electronic databases using a standardised set of risk predictors

- selection | use a selection tool to undertake further assessment of each identified patient’s modifiable risk and match their needs to the most appropriate integrated care interventions, which can be delivered via telephone or face to face interaction (these interventions generally require information not held in the electronic medical record)

PHM guides us to act as early as possible to keep people well, without focusing only on people in direct contact with services.

Primary care clinicians who work in this way describe a change, in that their job is not only about reactively providing appointments but proactively caring for the communities they serve as part of a broad multi-disciplinary team. This can be a more efficient, effective, and satisfying way to provide care, ‘reducing the churn in the system’ whilst addressing the root cause of the problem in a holistic and comprehensive manner. PCNs have been set up within ICSs to work this way.

Several case studies showing how population health management has been used effectively by both ICSs and PCNs can be found on the NHS England website.

Considerations when choosing/using tools for identifying patient cohorts

General practice does not have the specific resources needed to address the broader determinants of health. Issues like poor housing, school meals, fast food takeaways and the price of alcohol have a major impact on the physical and mental health of patients.

Traditionally, general practice has been poorly equipped to influence these factors, but social prescribers and health coaches within PCNs are hoping to change this for the better. Evidence is beginning to emerge to support this. You can read several case studies on the NHS England social prescribing page.

Professionals working in general practice are, however, well placed to understand the local factors that shape behaviours and lifestyles.

General practice clinicians actively look for the wider causes behind patient’s illnesses, often giving unique insight into the local factors influencing health and wellbeing in communities.

Any tool used to identify a cohort of patients is useful, but the identification of a patient cohort is just the start of managing that cohort’s health. The NHS Long Term Plan includes a major ambition to prevent 150,000 strokes, heart attacks and dementia cases over the next 10 years, holding firm the belief that early intervention to reduce the risks of serious illnesses in the population is much more cost effective and can lead to a more sustainable equitable health service for all.

How risk stratification/segmentation has been used to target interventions at a practice and PCN level

At practice level

General practice has been successfully using risk stratification and segmentation to identify those patients who can benefit from targeted management of their long-term conditions for several years.

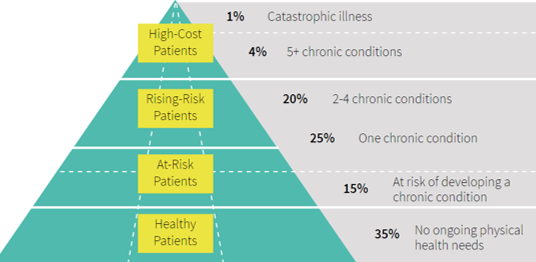

The infographic below shows how risk stratification can be used in relation to chronic illness:

Practice clinical systems have risk stratification tools built in, such as the QRISK calculator (versions 2 and 3 are in widespread use) and the electronic Frailty Index (eFI).

Adults aged 40 to 74 who attend general practice for an NHS health check should have their cardiovascular disease risk score calculated using the QRISK calculator. QRISK is used to identify those patients who have a combination of results that together put them at a higher risk of a stroke or heart attack. General practice can then manage the risk by appropriate medication and lifestyle advice as well as potential involvement from other partnership agencies such as local authority health and wellbeing services.

Frailty (rather than age) is an effective way of identifying people who may be at greater risk of future hospitalisation, care home admission or death. People living with severe frailty, for example, are at x4 greater risk annually of these outcomes. Older people with frailty who undergo surgery can have less successful outcomes if the frailty has not been identified prior to the operation.

This means population-level frailty identification and stratification can help plan for future health and social care demand whilst also targeting ways to help people age well.

Clinical data templates

Accurate recording of data is essential to support the development of PHM.

Clinical templates are used in primary care to manage many conditions/ presentations. Templates vary across localities, with the supplier, and content, usually agreed at ICS (previously CCG) level. The outcomes and core data collected will, however, be standardised across GP practices in England.

Data is extracted from GP clinical systems through the Calculating Quality Reporting Service (CQRS) which is an approvals, reporting, and payments calculation system for GP practices. CQRS helps practices to track, monitor and declare achievement for the QOF, directed enhanced services (DES) and vaccination and immunisation (V&I) programmes.

Data can be extracted either:

- automatically from the practice clinical records system through the General Practice Extraction Service (GPES) – GPES collects information for a wide range of purposes, including providing GP payments

- manually, directly into the CQRS

The NHS is currently developing a new, more secure and more efficient way to collect health data called the General Practice Data for Planning and Research data collection that will replace three hundred individual collections with one. This collection will not be used for QOF or payment purposes, or for direct care.

At PCN level

As primary care networks mature, they will increasingly be asked to use PHM to provide more proactive and targeted care to their populations. The use of PHM techniques will, therefore, be crucial to delivering the network contract DES over coming years.

A useful guide for PHM in PCNs can be found on the NHS Confederation website.

A data-led approach can help clinicians to identify who would benefit most from structured medication reviews, social prescribing, and other anticipatory care approaches.

By bringing together data on population need, PHM can also support primary care networks to understand how to make best use of additional roles funded through the network contract DES.

The following service requirements focus directly on PHM:

- structured medication reviews and medicines’ optimisation

- enhanced health in care homes

- early cancer diagnoses

- social prescribing service

- cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention and diagnosis

- tackling neighbourhood health inequalities

- anticipatory care (with community services)

- personalised care

At PCN level, services may have some variation across localities depending on the specific needs of the local population. ICSs will focus on the wider determinants of health (things like housing, employment, education).

Some immunisation and vaccination programs, such as seasonal influenza are currently a PCN target rather than an individual practice target. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of achievement of high percentage vaccination targets. In the case of COVID-19 this may have reduced disease severity and hospitalisation rates.

The legal basis for using patient data in this way

NHS and care organisations are committed to keeping patient information safe.

The UK Government has confirmed a significant amount of investment towards improving access to NHS data through Trusted Research Environments (TREs) and digital clinical trial services.

The NHS has rigorous processes in place for ensuring the data it manages is collected, processed and stored securely. Strict governance ensures that controlled access is only granted to organisations who clearly demonstrate that the data will be used to benefit patients and society as a whole. There is potential for data to be ‘sold’ in a pseudonymised format, or a completely anonymised and aggregated format, this is dependent upon the organisation requesting the data and the purpose of that request. Data is, however, never shared or sold for insurance or marketing purposes.

An overview of the General Practice Data for Planning and research (GPDPR) programme can be found on the NHS England website.

The NHS Long Term Plan talks about ICSs using data to enable sophisticated population health management approaches, allowing proactive anticipatory care models to be rolled out widely. Agreement will be needed to ensure there are suitable data linking processes in place, and governance processes are in place to regulate appropriate use of data to support proactive and personalised care in population health management.

There must be a clear lawful basis for the use of personal data. If data is effectively anonymised, it will not need a lawful basis under the 2018 Data Protection Act or need to meet the common law duty of confidentiality (CLDC). Careful consideration has to be given to:

- whether there is any sharing of personal data or pseudonymised data which could potentially be identified

- whether re-identification might be required

- how either of these are carried out in line with the law

For personal data to be processed it must meet a lawful basis under Article 6 of the UK General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). In addition, health data is classed as the more sensitive ‘special categories data’, so will need a further lawful basis under Article 9 of the UK GDPR.

To meet CLDC, patient data can also only be shared:

- if there is consent (explicit or implied)

- it is required by law (such as the Children Act 1989, for safeguarding purposes, powers for Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections, reporting of food poisoning, infectious diseases like measles and the powers given to NHS digital under section 259 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012)

- in response to a court order (where a judge orders that specific and relevant information must be provided, and to whom)

- if it can be justified in the public interest (where provision of the information outweighs the rights to privacy for the patient concerned and the public good of maintaining trust in the confidentiality of the service)

- legal support for the use of confidential patient information without consent under the Health Services (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002, under section 251 of the NHS Act 2006

Meeting the requirements of data protection and CLDC will also ensure that privacy rights under the Human Rights Act are met.

The Health Service Control of Patient Information Regulations 2002 (COPI) allow for the processing of confidential patient information for specific purposes. Regulation 3 allows processing of this data in relation to communicable diseases and other threats to public health. Covid-19 data was processed under this regulation. The sharing of data in this instance provided factual evidence on which many of the decisions for the management of the pandemic were based.

Benefits of PHM

PHM & Covid-19

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic highlighted the known link between poorer health outcomes, ethnicity, and deprivation. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) the forerunners to ICSs, worked with local authorities and the voluntary sector to identify people who needed more support and those with the most complex needs within their localities (shielded patients). This allowed for targeted efforts to protect certain populations through personalised care models, public health advice, testing and vaccination programs.

Reducing elective waiting times

As services restarted after the peak of the pandemic, health and care systems used PHM data to identify those with the greatest need, i.e., patients who have been waiting for appointments and procedures. In Surrey, for example, the ICS worked with provider organisations in Guildford and Waverley to identify almost 3,000 patients who were aged over 65 and on four or more elective waiting or follow-up lists.

PHM risks

While vendors (companies providing IT systems and services), service providers, and other stakeholders are starting to make headway with health data interoperability, moving patient information back and forth between disparate systems is still one of the foundational challenges of taking a population health approach to care.

ICSs must ensure that the various commitments that have been made to improving population health go beyond rhetoric, to a sustained effort at national, regional, and local levels.

Training and education

NHS England has introduced a population health management programme aimed at analysts and other health and care professionals working in population health, to support and build knowledge and skills within this area.

NHS England has also developed a PHM Academy which is a hub for information around PHM techniques and resources, as well as ongoing PHM work within the health and care sectors.

There are links below which explain PHM in much greater detail.

Related GPG content

Other helpful resources

- UK Government Office for Health Disparities, Local Health

- UK Government Office for Health Disparities, Public health profiles

- UK Government Office for Health Disparities, Strategic health asset planning and evaluation (SHAPE)

- NHS England, A Guide to population health management

- NHS England, Population health and prevention

- NHS England, COPI notice

- UK policy paper GOV.UK Prevention is better than cure

- NHS England PHM case studies

- NHS England, How data is protected

- PubMed, The essential role of population health during and beyond COVID-19

- GOV.uk, Health Matters: Preventing cardiovascular disease

- Digital Health Net £200m investment announced to improve access to NHS data (digitalhealth.net)