Foreword

The struggle to address racial inequalities and inequity in mental health services is a very personal journey for me. I am driven to fight for a fairer system where people from racialised communities no longer have significantly worse experiences and outcomes. I have lost two brothers, who throughout their lifetime grappled with long term mental health challenges, and sadly died young, Barry at age 53 and Carlton at 41. In 2023, I also lost my aunt, who died whilst in the care of mental health services. It has been extremely difficult for me to see how my loved ones were failed by mental health services where they endured racialised experiences. I live every day with the excruciating thought that if culturally appropriate care had been available for them, they would be alive today.

Despite numerous cross-government efforts over the past 18 years (Delivering race equality in mental health care: race equality action plan: a five year review 2014), people from Black and Black British groups are still four to five times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act than their white counterparts, have higher rates of being restrained in inpatient units, and are far more likely to encounter mental health services through the criminal justice system (GOV.UK Reforming the Mental Health Act). We also know people from other racialised groups have poorer mental health and access to mental healthcare, including increased use of crisis pathways, leading to more negative experiences and outcomes compared to the majority white British groups (Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK, 2022). The anti-racism approach of the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) has been coproduced, following the recommendations of the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act 2018, in order to tackle these issues I’m so pleased to be rolling it out across the country. The PCREF is for all racialised communities and is aimed at mental health trusts and other mental health service providers.

I have been working with vulnerable and racialised groups and communities for many years and have seen the disastrous impact that systemic racism and injustice has had upon so many peoples’ lives. The deaths in custody, whilst detained under the Mental Health Act , of people from racialised groups are nearly two times greater than other deaths in custody (INQUEST: Black, Asian, and Minoritised Ethnicities: Deaths in police custody). Cases like Kingsley Burell-Brown, Kevin Clarke, Sean Rigg and Olaseni Lewis, are painful reminders of a system that continues to dehumanise all racialised groups. This anti-racism framework caters for all racialised communities through naming racism, identifying how it operates in services and working with communities to organise and create responsive actions from these insights.

At NHS England, I have worked at the national level since 2015 to address the disparities racialised groups experience when it comes to mental health care, commissioning resources to support providers and commissioners to focus on co-creating more equitable services. Subsequent to being vice chair of England’s Mental Health Task Force, which led to the NHS Five Year Forward View for Mental Health, I was an advisory panel member on the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act (2018). Building on a similar recommendation from the Crisp Commission the review recommended the NHS develop an organisational competency framework to enable organisations to understand what steps they need to take to achieve practical improvements for individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Through coproduction, this anti-racism framework, otherwise known as the PCREF, has emerged.

I am humbled by the solid support and courage our NHS England leaders of mental health, Claire Murdoch, National Director for Mental Health and Professor Tim Kendall, National Clinical Director for Mental Health have shown as they welcomed the significant progress of the PCREF and announced:

It is vital for me that we elevate the voices of service users, carers, and communities to inform the service improvements we want to see through the collaborative participatory approach of the PCREF. The renewal of the social contract between citizens and the public sector is at the centre of the framework – its emphasis upon working transparently with constituents is critical to its success. Harnessing the power of a range of stakeholders makes this purposeful work move from groupthink to cognitive diversity, innovation and imagination – where lived experience is intrinsically valued in improving access, experience and outcomes for racialised communities. Comprehending the lived experience of racism, and its impacts upon health and wellbeing, is an essential part of this journey.

We have been working with four PCREF pilot mental health trusts and six early adopter sites who have been embedding the framework in different and innovative ways over the past three years, reflecting the needs of their local communities, and we have seen significant progress in these areas. Notably we even advanced this work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Every Trust’s journey will look different because no area’s population demographic, or constellation of services or communities, are the same, but these pilot trusts have shown us what is possible when we listen to local communities and work with them to deliver care that is culturally appropriate, trustworthy and meets their needs. Inaction in the face of need is a clear indicator of systemic racism in operation and our pilot trusts and early adopter sites have been proactive in naming racism, identifying how it is operating across their services and the anti-racism framework (PCREF) has served to focus attention on strategies and actionable insights to counter.

We all know it’s an iterative process but the journey towards services which are anti-racism, anti-oppressive, anti-discriminatory and are rights based has firmly begun. We plan to regularly review and update this anti-racism (PCREF) framework and supporting information to share what is working well and where improvements can be made. We have developed the PCREF positive practice guide, which has been established through our way of working with our pilot trusts. It is envisioned that the ongoing feedback that emerges from the national roll-out will highlight learning that will strengthen future versions of the PCREF.

I am truly inspired by the appetite of a wide range of stakeholders, including service users, carers, the voluntary sector and community groups, the workforce and organisational leadership to join this collective anti-racism effort. The PCREF yields opportunities for innovation and creativity in all services – indeed transformed and new services will emerge. Leading this work has shown me what fellow human beings are capable of, when together, with a sense of liberation and empowerment, we proactively embrace a shared vision. We are embracing collective intelligence to ensure collective impact in the best interest of the people. We can do it and we can do it exceedingly well.

We have come a long way since the 1983 Mental Health Act was first passed in law, with the closing of the final remaining Victorian asylums and a move towards whole person care in communities; but there is still an enormous amount of work to do. I am ambitious yet pragmatic for our people – we are only in the foothills of this vision, and we still have this steep mountain to climb, but the foundations we have set by creating the PCREF will allow us to start taking strides towards positive change and embed race equity for people from racialised communities in all our mental health service provision.

Purpose of this document

This document outlines the participatory approach to anti-racism that mental health trusts and mental health providers should take to improve experiences of care for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities. The Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) sets out the legislative and regulatory context for advancing mental health equalities and will assist mental health trusts and other mental health providers to comply with their obligations. It provides practical steps, co-developed with PCREF pilot trusts and early adopter sites, their ethnic led voluntary sector partners, patients, carers and communities, and the regulators to deliver culturally responsive care.

Structure of the document

- ‘How to implement the framework’ outlines practical steps mental health trusts and other mental health providers must take to deliver part 1, part 2 and part 3 of the framework. For more information on each part of the PCREF please refer to the section on ‘Implementing the PCREF’.

- The annexes include information on the legislative and regulatory context (Part 1) organisational competency examples (Part 2) and the patient and carer experience tools and measures available (Part 3).

- In addition to this document, there is a significant number of documents on the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework including positive practice guide on how Trusts have embedded the PCREF, available on the Future NHS Collaboration platform.

A note on language

The PCREF was co-developed with racialised communities, patients and carers. As a first step, it was important to set out the terminology related to the race and cultural identity of people from communities disproportionately impacted when accessing mental health services. It was important to acknowledge that current legislative terminology used to describe certain race and cultural identity do not always reflect people’s unique intersectional needs and lived experiences.

This document uses the terms ‘racialised communities’ which refers to ethnic, racial and cultural communities who are minoritised populations in England, have been racialised (Centre for Mental Health – Guide to race and ethnicity terminology), and who experience marginalisation.

The term ‘ethnically and culturally diverse’ refers to people with distinct cultural or ethnic identities, which can include diverse language groups and communities upholding specific cultural customs and spiritual beliefs.

The term ‘ethnic groups’ includes white minorities, such as Gypsy, Roma, and Irish Traveller groups (Central Government – writing about ethnicity), whilst recognising homogenising ethnic groups ignores the diversity of experiences between groups (NHS Race and Health Observatory – The Power of Language).

Audience for this framework

This anti-racism framework is written for mental health trusts, mental health providers which includes the independent sector, mental health secure care services, local authorities and commissioners, children and adult social care services, voluntary sector organisations, faith led organisations, the education sector and the police forces across England, who deliver support to children and young people, adults and older adults with mental health needs.

Executive summary

Improving mental health care for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities has been a long-standing challenge for mental health services and people from these backgrounds are more likely to have poorer health outcomes and experiences than those from the UK majority population.

NHS England committed to taking forward and developing the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) following the publication of the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act (MHA). The Independent Review of the MHA describes the PCREF as ‘a new community-driven organisational competence framework tool that should enable Trusts to understand what practical steps they need to take to meet the needs of diverse ethnic backgrounds.’

The PCREF cannot be applied in isolation. The NHS Constitution commits to providing a comprehensive service available to all irrespective of race. The NHS has a duty to every individual that it serves and must respect their human rights, while also promoting equality through the services it provides and pays particular attention to groups where health services are not equitable for disadvantaged groups and therefore improvements in health and life expectancy are not keeping pace with the rest of the population. The NHS needs to proactively address race inequalities and inequities, so that racialised communities can have a better chance in improving their access, experience and outcomes when accessing health services. In 2021, NHS England published the Core20PLUS5 approach for adults and children and young people, which explicitly re-states the need to reduce inequalities faced by racialised and ethnic groups across all parts of the health service.

NHS England published its first Advancing Mental Health Equalities Strategy in 2020. The strategy outlined the core actions needed to bridge the gaps for communities faring the worst outcomes in mental health services. The PCREF is an important part of the strategy and will act as an anti-racism, race equity and accountability framework, supporting mental health trusts and other mental health providers to demonstrate how they are meeting their core legislative requirements and how they can improve the cultural competence of their organisation as they fulfil their duties. This cultural shift will aid improved access, experience, and outcomes for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities. It will also help Trusts and other mental health providers become anti-racism organisations. We know that anti-racism is a process with three tasks: 1) Name racism. 2) Ask “How is racism operating here?” 3) Organise and act. These tasks are sequential, iterative, and may well span generations (Jones C, 2023).

The PCREF has been co-produced with experts by experience, carers of mental health challenges, and PCREF pilot trusts and early adopter sites who have partnered with ethnic led voluntary sector organisations. The PCREF’s commitment to centring the voices of patients and carers is in line with NHS England’s commitment to improving patient experience (NHS England: Patient experience improvement framework) and carer experience (NHS England’s Commitment to Carers). The Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the Equality Human Rights Commission (EHRC) have equally played a proactive role in strengthening the PCREF from a legislative and regulatory perspective.

The challenges that racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse groups experience are well documented. In some communities, sharing a mental health diagnosis or treatment can be stigmatised, which can lead to individuals being hesitant to come forward to seek support. As a result, some individuals only encounter NHS mental health services when in crisis – which could have a detrimental impact on both their mental health and experiences of mental health services (NHS England: The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health). We know in some cases, the poor quality of care and the inappropriate use of force (New Guidance on Use of Force Act 2018 (Mental Health Units), has resulted in serious harm and even death in settings where racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities are overrepresented (especially Black/Black British communities).

NHS England has made a concerted effort to overcome some of these barriers through working with the system, this includes the recent publication of NHS England’s Equality, diversity and inclusion improvement plan which recognises the strength for a diverse workforce will only harness improving health equality access, improvement and outcomes overall for the most vulnerable groups in our society. However, we still have a long way to go, and Trusts and mental health providers will need to embed the systematic method of the PCREF, with the help of integrated care boards (ICBs), to support in advancing equality.

NHS England does not underestimate the challenges that are present in advancing equalities, and even more so the challenges experienced by racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities. Throughout the implementation of the PCREF we will continue to review its impact and share learning so that we can strengthen the alignment to NHS England’s vision to tackling race inequalities and inequities. We will achieve this by working collaboratively with partners.

Making the case for change

We know from the data we have available that people from racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities can have very different experiences of mental health services. For example, NHS England’s data has consistently shown that people from racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities (especially Black/Black British communities) are more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act and are more likely to be detained in hospital for longer when compared to other ethnicities. Details on the statistical data is available from NHS England’s Mental Health Act dashboard.

While the causes of poor experience are varied, communities frequently report a number of consistent barriers including absence of cultural competence or cultural safety (BMC research 2009) (i.e. the ability of providers and organisations to examine themselves and the potential impact of their own culture on clinical practices and to effectively deliver healthcare services that meet the social, cultural, and linguistic needs of patients), stigma, discriminatory behaviours (explicit and implicit), lack of trust, and structural, institutional and clinical practices that disadvantage racialised groups. For example, we know that Black African and Caribbean people with psychosis are less likely to be offered least restrictive interventions and or evidence-based treatments (Das-Munsshi et al, 2018) and that British Muslims and people from other religious backgrounds have experienced discrimination and racism (Meer, S et al 2014) and (Anik et al 2021). We are also aware that rates of self-harm are highest in racialised communities for example in young Black females aged 16–34 years compared with White females (Cooper J et al 2012).

Furthermore, racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities are not homogenous groups and have very different experiences in relation to mental health services.

We must proactively address these inequalities, or we risk even deeper disparities and worse outcomes, particularly as we know the prevalence of mental health challenges is greater than it was before the pandemic. The complexity is undeniable. The potential for improvement is palpable.

Since the inception of PCREF three years ago, pilot trusts and early adopter sites have significantly strengthened their understanding of their local population need. Attending to racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities, case studies of improvements have been published on the Future NHS Collaboration platform. This has demonstrated the importance of mental health trusts naming racism and identifying how it operates in their context so that they can dismantle racism and take action to become inclusive.

Introduction

What does the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework mean in practice?

At the heart of developing the PCREF is the commitment to improve the access, experiences and outcomes of racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities, patients and carers by respectfully drawing upon their experiences.

The PCREF is a participatory approach (Patient and public participation in commissioning health and care: statutory guidance for CCGs and NHS England, and resource guide on Public Participation) envisaged to be a ‘social contract’ (What We Owe Each Other by Minouche Shafik) between mental health service providers, education settings, local authorities, criminal justice services, social care providers and the independent sector, for patients, carers, and community members, as well as voluntary sector organisations. Mental health trusts and mental health providers are responsible for the delivery of the PCREF in collaboration with their partners, including local authorities, commissioners, communities, patients and carers from racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

As an anti-racism approach, at its core, the PCREF aims to:

Aims | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Mental health trusts and mental health providers (leaders and staff) |

|

| Patients and carers |

|

The PCREF is split into three core components:

- Part 1 – Legislative and regulatory obligations (Leadership and governance): Legislation has been identified that applies to all NHS mental health trusts and mental health providers in fulfilling their statutory duties, and leaders of the Trusts and mental health providers will need to ensure these core pieces of legislation are complied with across their organisation.

- Part 2 – National organisational competencies: aligns with the vision in the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act 2018 (MHA). Through a co-production process, six organisational competencies have been identified working with racialised communities, patients and carers. Trusts and mental health providers should work with their communities and patients and carers to assess how they fair against the six organisational competencies (and any more identified as local priorities) and co-develop a plan of action to improve them.

- Part 3 – The patient and carers feedback mechanism: which seeks to embed patient and carer voice at the heart of the planning, implementation and learning cycles.

Parts one, two and three of the framework purposefully interacts with each other in a systematic, inter-dependent and iterative way – this intentionally cultivates a learning organisation – as it strives to build trust with the communities being served. The PCREF harnesses a range of data, views that data from multiple perspectives, and seeks to change the poor trajectory of that data story for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities who use mental health services.

The PCREF applies to all mental health pathways i.e. community mental health services, inpatient services, secure care, talking therapies, children and young people, perinatal etc The PCREF apples to older adults (65 plus), adults (18-64), children and young people (0-25). Trusts and mental health providers must also ensure that intersectional needs, including neurodiversity and socio-economic backgrounds, are fundamentally assessed. Trusts and mental health providers will be required to co-develop plans that offer a culturally appropriate care model for racialised, ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

The implementation of the PCREF will also support CQC and EHRC’s inspection processes in line with their regulatory duties.

For this reason, each NHS mental health trust and mental health providers will be required to have a PCREF in place by the end of the financial year in 2024/25 as set out in NHS Standard Contract. This means the PCREF will be mandatory and will need to be incorporated as part of Trusts’ and mental health providers business as usual planning. Trusts and mental health providers are expected to have a nominated lead at board level to drive forward and embed a local PCREF plan which encompasses the three core components above, detailing actions, timeframes and intended outcomes. Importantly, the development, implementation, and review of local PCREF plans must be done in equal partnership with racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities and must be published annually on Trusts’ and mental health providers websites. This provides accountability and transparency with communities served as to the progress being made to improve the racialised experience of mental health service provision.

Prevention and early intervention will be key to addressing some of the long standing racial and systemic barriers racialised ethnically and culturally diverse communities experience and it will require cross sector working to support the implementation of the PCREF. One example is the recent publication from the government on Suicide prevention in England: 5-year cross-sector strategy, which the mental health sector will need to pay attention to, particularly as we know the suicide rates on ethically and culturally diverse communities are at increased risks of suicide compared to other ethnicities (Office for National Statistics: Mortality from leading causes of death by ethnic group, England and Wales 2012-2019).

It will also be important for Trusts and mental health providers to work with partners in other sectors. For example:

- Working with local authorities and their commissioners as aligned to NHS England’s integrated care systems and integrated care boards on partnership working and meeting the local population needs particularly attention paid to racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities needs.

- Working with schools and educational settings when engaging with children and young people from racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities, (refer to the Future NHS Collaboration platform for information on engaging children and young people from Transformation Partners in Health and Care);

- Working with faith leaders to understand the experiences of people belonging to a particular faith and how Trusts and mental health providers are to improve access, experience and outcomes and offer a tailored support that is more responsive to religious needs.

- Working with police to build trust and confidence when engaging with racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities so that improved tailored support is offered, and the least restrictive interventions are explored. Recent publication of the National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person (NPA:RCRP) recognises the importance of the PCREF and should help support the reduction of racialised groups accessing urgent mental health pathways, who disproportionately experience restrictive interventions and are more likely to access mental health care via the criminal justice system.

An example of a high-level project milestones co-produced with Trusts can be used to embed the PCREF locally can be found on the Future NHS Collaboration platform.

Mental Health Act reforms

The PCREF forms part of the wider planned legislative reforms of the Mental Health Act, which are being taken forward by the Government, as highlighted in the Government’s white paper on Reforming the Mental Health Act. Of further relevance to the PCREF, the Government will review and update the accompanying MHA Code of Practice. This will include a particular focus on ensuring the Code of Practice suitably identifies and addresses opportunities for improving how people from ethnically and culturally diverse backgrounds experience the Act, tackling disparities and ensuring fair treatment for all.

The updated version of the MHA Code of Practice will be published following Royal Assent of the draft Mental Health Bill which is currently progressing through Parliament, and will sit alongside and complement the PCREF and wider non-legislative plans – including, for example, the Department of Health and Social Care’s pilots of culturally appropriate advocacy, which is exploring opportunities for addressing racial disparities in the access and support available from independent MHA advocacy services.

Implementing the framework

This section sets out how Trusts and mental health providers will be required to deliver on each part of the PCREF and outlines practical steps Trusts and mental health providers should take in fulfilling their statutory duties. This is supported by existing guidance and material available, including:

- Working Well Together: Evidence and tools to enable co-production in mental health commissioning, which was also developed by NCCMH and aims to improve local strategic decisions about current and future mental health services by working with communities, including those facing inequalities.

- Rapid Response: Covid-19 and Co-production in Health and Social Care Research, Policy and Practice; Volume 1: The Challenges and Necessity of Co-production; Volume 2: Co-production Methods and Working Together at a Distance.

- An IAPT positive practice guide (now known as NHS Talking Therapies) for ethnic minority communities and provides helpful guidance for practitioners on how to achieve access and outcome equity for the Black, Asian Minority Ethnic community. There are similar positive practice guides for other groups, such as older people and veterans.

- The Advancing Mental Health Equality resource, developed by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). This provides detailed guidance and methods to identify and reduce inequalities related to mental health support, care and treatment.

NHS England, together with the pilot trusts and early adopter sites, has developed positive practice case studies, highlighting the work of mental health trusts in implementing the PCREF so that we can embed further learning. To access this information, please refer to the Future NHS Collaboration platform.

Part 1 – Leadership and governance

A commitment to a strong leadership and a governance structure is required for Trusts and mental health providers to deliver PCREF Part 1. To assist Trusts and mental health providers, NHS England has identified 12 key legislative and regulatory requirements, which apply to Trusts and mental health providers, and which impact upon racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

To enable delivery against these requirements and the implementation of the PCREF, each Trust and mental health providers will be expected to embed the PCREF in their governance structures. Based on PCREF pilot trusts learnings and recommendations, each Trust and mental health providers should have in place a nominated executive lead at Trust and mental health providers board level who is accountable for the delivery and oversight of the PCREF to evidence how Trusts and mental health providers are:

- elevating the voices of community representatives within Trusts’ / mental health providers governance structures

- establishing partnerships with Local Authorities and voluntary sector organisations to engage on local priorities

- implementing culturally appropriate care

- committing to become an anti-racism organisation

Please refer to the Future NHS Collaboration platform for good practice examples from the pilot trusts and early adopter sites evidencing the PCREF at a leadership and governance level. PCREF pilot trusts will continue to build on strengthening their governance and leadership structures and will share their findings in a range of ways, including through our communities of practice, to help newer Trusts / mental health providers and wider system improvements.

Legislation

The following legislation includes duties for Trusts and mental health providers that impact on racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities:

- NHS Act 2006

- Carers Leave Act 2023

- The Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018

- Children Act 2004

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Mental Health Act 1983

- Health and Care Act 2022

- Health and Social Care Act 2008

- Equality Act 2010

- Mental Capacity Act 2005

- Children and Families Act 2014

- Care Act 2014

Trusts and mental health providers are to actively demonstrate how they are reducing inequalities for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities. To do this, Trusts and mental health providers are encouraged to review the specific recommendations of the Mental Health Act (MHA) Review 2018, and the key legislation referred to above, along with relevant supplementary documents and guidance. For further details on the legislation and supplementary documents, please refer to Annex A.

The Mental Health Act dashboard and the Restrictive Interventions dashboard (Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018) were also created to support Trusts and mental health providers in fulfilling their duties and will provide further sources of ethnicity related data, as identified in PCREF Part 1, to support the improvement activities of PCREF Part 2. Please also refer to NHS England’s Data quality guidance on protected characteristics and other vulnerable groups.

The below section requires trusts and mental health providers to evidence how they are fulfilling their core requirements from a racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse lens. This is not an exhaustive list, and trusts and mental health providers must consider all relevant legislation and guidance.

1: Practices that work towards the shared values of dignity, fairness, equality, equity, respect, least restrictive practices, independence, empowerment and involvement are routinely published to national datasets (Mental Health Service Data Sets – (MHSDS) and Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) objectives annually). Trusts and mental health providers should have in place a responsible lead person whose role will be to collect and monitor data broken down by ethnicity and publish the data at the end of each financial year.

This should include at a minimum:

1. The number of cases of detention under the MHA, and the cause and duration of these detentions.

2. Restraint including the type of restraint (physical, mechanical, chemical or use of isolation) and by ethnicity, age and gender as aligned by the MHA Code of Practice guiding principles.

3. As required by Core20Plus5 Trusts:

a. physical health checks for those adults (18+) with Severe Mental Illness (SMI).

b. improve access rates to Children and Young People’s mental health services for 0-17 year olds.

4. A sample of locally agreed access, experience and outcomes metrics where inequalities are the most evident. This may include Mental Health Act detentions (i.e. the duration of community treatment orders, out of area placements, aftercare placements and suicidal rates by ethnicity).

5. Trusts/mental health providers will report on any deaths in mental health inpatient units to CQC by protected characteristics. Please also refer to CQC’s notifications on incidents.

Trusts/and mental health providers should provide a narrative explanation of data trends and over time Trusts and mental health providers should be able to demonstrate reduced inequalities. To support Trusts and mental health providers, national mental health statistical data are published on the MHSDS where NHS England have developed a mental health data quality dashboard on protected characteristics. Please also refer to NHS England’s Data quality guidance on protected characteristics and other vulnerable groups.

Trusts will also be required to provide evidence of the implementation of the PCREF within the new guidance of EDS 2022, which will determine the grading and scoring.

Role of our regulators

NHS England is working closely with the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and the Equality Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in the development of the PCREF. The CQC has developed a new assessment framework which will start to roll out in autumn 2023. NHS Trusts and mental health providers must continue to demonstrate performance against the five key questions, i.e., that they are safe, effective, caring, responsive and well led.

The assessment framework has quality statements which have been co-produced, and are the standards that providers, commissioners and system leaders should live up to; over a third of these are directly related to equality risks in health and care and the workforce. Implementation of the PCREF will be one of the pieces of evidence that CQC will consider when scoring quality statements as part of their new regulatory approach. In line with CQC’s strategy and core purpose, they have also recently published their Equality objectives which aim to tackle inequality by focusing on people most likely to have a poorer experience of care.

CQC understand that it is not possible to deliver good quality care without rights within care, cultures, and systems. CQC’s refreshed human rights approach, ‘Humanity into Action’, is to be published in late-2023, and outlines CQC’s intention to create a step change in thinking about, protecting, and upholding human rights. The guidance will be for health and care providers, people who use services, commissioners, and CQC colleagues including their partners and stakeholders. The implementation of the PCREF will help strengthen this work from a human rights perspective.

EHRC has responsibility for monitoring human rights, challenging discrimination and promoting equality including the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED). The EHRC has launched a new programme to monitor how different sectors are complying with the requirements of the PSED. In February 2023, EHRC wrote to ICBs reminding them of their responsibilities under the PSED and the specific equality duties (SEDs), noting that it will be monitoring ICBs’ compliance with the duty. The PCREF’s local application within Trusts and mental health providers will be fundamental to this.

Areas of focus for EHRC will include:

- tackling disproportionate rates of detention of ethnic minority people under the Mental Health Act 1983

- tackling the inappropriate detention of people with a learning disability and autism

- considering equality within the NHS workforce, including the experience of low paid ethnic minority staff.

EHRC also works closely with the CQC through their memorandum of understanding and has launched a new programme to monitor how different sectors are complying with the requirements of the PSED.

Part 2 – National organisational competencies

PCREF Part 2 outlines critical competencies for Trusts and mental health providers, and mental health service provisions, these help to focus service transformation to better meet the needs of racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

NHS England has worked alongside PCREF pilot trusts, early adopter sites, communities, NHS staff, voluntary sector organisations and other key stakeholders over the past three years working to identify what a ‘culturally competent’ Trust is. Views were wide-ranging and varied depending on the community make-up, local context, and existing practices and approaches within each Trust.

The six most consistent focus areas identified as national organisational competencies to improve the experience of racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities were:

- Cultural awareness

- Staff knowledge and awareness

- Partnership working

- Co-production

- Workforce

- Co-learning

However, there is also widespread recognition that other local priorities may be identified by communities, Trusts and mental health providers which are equally important to improve, and these should be added as required.

Each pilot trust and early adopter sites has been working with their local community networks, and their ethnic led voluntary sector organisations, to identify opportunities to strengthen, and purposefully deliver, these six organisational competencies to improve access, experience and outcomes for racialised communities. We aim to continue to test these national organisational competencies with Trusts and with mental health providers as they continue to work with their local communities and implement co-produced action plans to strengthen them. The evolving PCREF positive practice case studies will also assist through sharing learning across the country and is supported by the NHS England’s Advancing Mental Health Equalities Taskforce and the PCREF Data Quality and Research sub-group.

To find out more on the engagement findings carried out by the pilot trusts in 2021 and their voluntary sector partners, representing ethnically and culturally diverse communities, please refer to the Future NHS Collaboration platform.

Assessing how your trust and mental health providers fares against the six national organisational competencies

The national organisational competencies should demonstrate what good looks like at an organisational level and at a service level, along with the practical steps Trusts and mental health providers should be taking to improve experiences of care for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities. NHS England has co-produced an example of ‘what good looks like’ for each of the six national organisational competencies, and opportunities to improve them, with PCREF pilot trusts, racialised and culturally diverse communities and ethnic led VCSE organisations. This is available at Annex B.

It is worth noting that opportunities to improve these six national organisational competencies often interlink.

Alongside the good practice examples, a self-assessment checklist has been co-developed to be used as a guide for Trusts and mental health providers, along with service users, carers, communities, and partners, to reflect on whether they are progressing on their improvements against each of the organisational competencies. The checklist can also be found at Annex B. We encourage Trusts and mental health providers to continue to build on developing the self-assessment check list as this does not represent an exhaustive list of good practice and Trusts / mental health providers will be required to ensure that the improvements meet their local population’s needs with reference to equity and equalities.

Once the PCREF is launched, the expectation is that all Trusts and mental health providers will co-produce a clear set of measurable actions. These would be routinely monitored by both the Trust’s and mental health providers board and other governance structures in order to ascertain how the Trust and mental health providers fare against these competencies and agree priorities for improvement. To help Trusts and mental health providers evidence PCREF Part 2, a template is available within the positive practice case studies, for Trusts and mental health providers to evidence their scale of improvement plan, please refer to the Future NHS Collaboration platform.

Part 3: Patient and carers feedback mechanism

At the heart of developing and testing the PCREF is the local commitment from Trusts and mental health providers to improve the experiences and outcomes of racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

PCREF Part 3 will support Trusts and mental health providers to improve the routine use and collection of patient experience and outcomes data both nationally and locally and put in place an approach which allows learning from experience. This, combined with the routine monitoring of the core metrics from Part 1, should provide a well-rounded view of how patients and carers are faring, how they feel about the service, and whether the actions the Trust and mental health providers are currently undertaking are demonstrating an impact in addressing racism and discrimination.

It is vital that Trusts and mental health providers understand the experiences and feedback of racialised ethnically and culturally diverse patients, carers and communities and that information collated via the national datasets is used to drive these changes locally.

PCREF Part 3 focuses on:

- Agreeing the most suitable and impactful tool to measure the experience of ethnically and culturally diverse patients and carers at a local level. Further, evidencing how these experiences vary, and how feedback is being taken on board in a transparent way.

- Routinely flow access and outcomes measures, in line with national requirements to national mental health datasets (i.e. Talking Therapies recovery) to better understand the impact of mental health services of racialised ethically and culturally diverse communities accessing/receiving care from Trusts and mental health providers.

- Agreeing/co-producing with racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse experts by experience which of these access, experience and outcomes measures to monitor routinely at a Trust and mental health provider board level. This should be alongside the existing nationally recommended outcome and experience tools, as well as the metrics already specified in Part 1. Please refer to Annex C on outcome and experience tools.

We know from research there is a gap in understanding the outcomes of racialised individuals. National outcome tools used by Trusts are not equipped to recognise culturally appropriate care, or discrimination, for patients and carers, and data can be incomplete in these areas. Therefore, Trusts and mental health providers are encouraged to explore opportunities to develop culturally informed outcome measure (Centre for Mental Health 2022) that are tailored for their patients, carers and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

Nationally, mental health trusts and mental health providers are required to submit outcome measures to national datasets for IAPT, Adult Community, Children and Young Peoples and Perinatal mental health services. The use of outcomes and experience measures will support Trusts and mental health providers to get a better understanding of:

- Needs of the service user and areas of progress in relation to the service and staff, their care and wellbeing, and their symptoms/functioning leading to more personalised care.

- Identifying gaps in the service, demonstrating a service’s accountability to improve delivery of care for racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

- Where Trusts and mental health providers are benchmarked to enable learning from each other to embed cultural changes for improving patient experience and outcomes.

- The impact of mental health activity in a local system.

Over the next financial year, pilot trusts and early adopter sites, will be strengthening their approach to collecting and flowing outcome measures, and learning from inequalities where they exist. This should include an understanding of intersectionality across protected characteristics and other socio-economic factors. Pilot trusts and early adopter sites will also be assessing which outcome measures are the most insightful in supporting their local PCREF plan and will share their good learnings during the implementation of PCREF.

In addition, each pilot trust and early adopter sites will be testing ways to make the feedback-loop with communities, patient, carers, and the workforce more transparent. Ensuring the approach is trauma informed, timelier and more accessible, and assessing whether follow up on monitoring of feedback has achieved the desired improved impact, this could include qualitative feedback via patient and carer satisfaction surveys and or complaints which Trusts and mental health providers are to review as part of their governance structures (as identified in Part 1 of the PCREF). For further guidance a list of patient experience and outcome tools is available in Annex C. Pilot trusts and early adopter sites will provide good practice examples as it emerges on the implementation of PCREF Part 3. This can be used by Trusts and by mental health providers to make these further improvements as their implementation of the PCREF evolves.

We encourage Trusts and mental health providers to ensure they equip their workforce with the tools/skills needed to work with racialised ethnically and culturally diverse communities as outlined in PCREF Part 2 on organisation competencies for the workforce.

Further information is available on the national Mental Health Outcomes programme.

Next steps

The PCREF is an evolving and iterative process and mental health trusts in partnership with racialised ethnically and culturally diverse patients, carers, communities, and ethnic led voluntary sector partners will need to commit to implementing the PCREF across their organisation as outlined in this guidance. Alongside Trusts and mental health providers, there needs to be a system wide approach from ICB’s to support in the delivery of the PCREF as we move forward to help improve access, experience and outcomes for racialised ethnically and culturally diverse communities across all mental health service provision.

NHS England will continue to strengthen the anti-racism approach of the PCREF and share lessons learnt. Over time we expect racial inequalities and inequities to improve as services offered by Trusts and mental health providers become more culturally responsive as anti-racism is embedded. Critical to the success of the PCREF will be the Trust’s and mental health providers leadership in their commitment to progress PCREF and build trusting, transparent and sustainable relationships with the communities impacted the most.

NHS England will keep the PCREF and its supporting information under review so that it can continue to document what good practice looks like. The PCREF positive practice case studies will also assist in the learning, and review, along with NHS England’s Advancing Mental Health Equalities Taskforce and the PCREF Data Quality and Research sub-group.

Annex A – Part 1 – Evidence, policies, and guidance

PCREF Part 1 – core duties

The below highlights the specific core duties of each Act and the specific statutory duties that may apply to supporting the implementation of the PCREF and supplementary documents and guidance to support Trusts and mental health providers. Note this list is not exhaustive and serves as a guide only.

Human Rights Act (HRA)1988

Statutory duties

All public bodies (like mental health trusts, courts, police, local authorities, hospitals) and other bodies carrying out public functions are to respect and protect people’s human rights. These rights are based on shared values like dignity, fairness, equality, respect and independence.

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

The following documents provide further detailed guidance on human rights when accessing mental health services for patients and professionals:

- Notification of Rights when detained under the Mental Health Act in England (civil section)

- Notifications of Rights when detained under the Mental Health Act in England (forensic section)

- Mental Health, Mental Capacity and Human Rights – practitioner toolkits

- Code of practice: Mental Health Act 1983

- Human Rights Framework for restraint

- Human Rights Framework for Adults in Detention

- Preventing deaths in detention of adults with mental health conditions

Legislation

Equality Act 2010 and the (Specific Duties and Public Authorities) of the Equality Act 2010

Statutory duties

- Section 149 of the Equality Act – Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED)

- Section 20 – 22 of the Equality Act – Reasonable Adjustments – Duty to make reasonable adjustments.

- Section 20 – 29 of the Equality Act – discrimination in the provision of goods and services and in exercising public functions.

- Section 158 and 159 Positive Action – Positive action measures may be used to alleviate disadvantage, reduce under-representation, and meet particular needs.

- The Equality Act 2010 (Specific Duties and Public Authorities) Regulations 2017 – aim to ensure that public authorities can better demonstrate compliance with the duties under the Equality Act 2010. The Regulations required public authorities to prepare and publish equality objectives, setting out what they intend to achieve in order to further the aims of the PSED at least every 4 years, and to publish information demonstrating their compliance with the duty.

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

NHS England has introduced some supplementary frameworks to support Trusts in evidencing positive action, these include:

- NHS England Equality Delivery System 2022 (EDS 2022): The EDS was developed by the NHS to help NHS organisations to improve system change on the services provided to their local communities and to improve work environments, free from discrimination aligned to NHS Long Term Plan in its commitment to be an inclusive NHS that is fair and accessible to all.

- The EDS includes three domains (patients, leadership and workforce) and will require Trusts to provide evidence of the implementation of the PCREF, which will determine the grading and scoring within the EDS 2022.

- Workforce Race Equality Standard (WRES) – Developed by NHS as a tool to measure improvements across all NHS services in the workforce with respect to Black, Asian and ethnically and culturally diverse staff. Trusts are required to publish data from a series of agreed indicators in order to ensure transparency on where these improvements are and to maintain inclusive workplace for Black, Asian and ethnically and culturally diverse staff.

- Workforce Disability Equality Standard (WDES) – The Workforce Disability Equality Standard (WDES) is a set of ten specific measures (metrics) which enables NHS organisations to compare the workplace and career experiences of disabled and non-disabled staff. NHS organisations use the metrics data to develop and publish an action plan.

- It should be noted that WRES and WDES are mandated by the standard NHS contract.

Mental Health Act 1983 and its Code of Practice applies to all providers that are registered with CQC to assess and treat patients who are detained under the MHA.

Please note there is no minimum age for use of Mental Health Act and its Code of Practise.

Statutory duties

Chapter 1 of the MHA Code of Practice sets out the overarching principles to be considered when making decisions under the Act.

- Section 2 – admission for assessment

- Section 3 – admission for treatment

- Section 4 – emergency admission

- Section 5 (2 and 4) – Hospital Holding Powers

- Section 12 – General provisions as to medical recommendations

- Section 117 – duty to provide aftercare

- Section 135 and Section 136 – removal of a mentally disordered person from patient’s home and or a public place to a place of safety

- All Part 3 (sections 35-55) – Patients Concerned in Criminal Proceedings or under Sentence

- Community Treatment Orders (section 17a, 17c,17d, 17g, 20b) – in-patients to be discharged with some conditions (medical treatment and preventing harm)

- Conditional Discharge – detained under section 37- 41 (where applicable)

- S130a – Independent Advocacy of the Mental Health Act

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

- Mental Health Act (MHA) Review 2018 – key recommendations from the African and Caribbean sub group

- NHSE MHA dashboard – Data

- Mental Health Act 1983: Code of Practice

Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its code of practice

The aim of the MCA 2005 is to promote and safeguard decision-making within a legal framework. The Act sets out parameters by which capacity can be assessed and those lacking capacity are supported as much as possible to make decisions.

Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019

The Liberty Protection Safeguards (the LPS) are a new system introduced by the UK Mental Capacity (Amendment) Act 2019 that will replace the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) once implemented.Statutory duties

The following requirements under the Act are especially relevant for PCREF:

- Section 1 of the MCA sets out the five ‘statutory principles’ – the values that underpin the legal requirements in the Act

- Sections 2–4 – Assessment of capacity and best interests decision-making

- Section 5 and 7 – Care treatment/goods and services for those providing care where the person lacks capacity and protected from liability

- Section 6 – Restraint or deprivation of liberty

- Section 9, 10 and 11 – Lasting power of attorney

- Section 21 – Court of Protection to transfer cases concerning children

- Section 24-26 – Advance decision

- Section 35-41 – set up a new Independent Mental Capacity Advocates (IMCA) service that provides safeguards for people

- Section 42 – sets out the purpose of the MCA Code of Practice

- Section 44 – Ill treatment and wilful neglect

- Section 45 – Court of Protection

- Mental Health, Mental Capacity and Human Rights – practitioner toolkits

- CQC’s supplementary guidance on capacity and guidance to consent in under 18s

- The MHA Code of practice chapter 19 references the care of CYP in mental health units and the relationship between the legal frameworks. CQC consider the MHA code of practice in their regulation work with providers.

The Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018 and its statutory guidance

The aim of the Act and the statutory guidance is to clearly set out the measures that are needed to both:

- reduce the use of force

- ensure accountability and transparency about the use of force in our mental health units

This must be in all parts of the organisation, from executive boards to staff directly involved in patient care and treatment.

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) have published the statutory guidance that sets out in more detail how to implement the requirements of the act.Statutory duties

The following requirements specifically impact racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities for Trusts to have due regards (note that the list is not exhaustive).

They are:

- Section 2 – mental health service providers operating a mental health unit to appoint a ‘responsible person’ who will be accountable for ensuring the requirements in the Act are carried out.

- Section 3 – the responsible person for each mental health unit must publish a policy regarding the use of force by staff who work in that unit. The written policy will set out the steps that the unit will be taken to reduce the use of force by staff who work in the unit.

- Section 4 – the responsible person for each mental health unit must publish information for patients about their rights in relation to the use of force by staff who work in that unit.

- Section 5 – the responsible person for each mental health unit must ensure staff receive appropriate training in the use of force. This statutory guidance sets out what that training should cover

- Section 6 – the responsible person for each mental health unit must keep records of any use of force on a patient by staff who work in that unit, which includes demographic data across the protected characteristics in the Equality Act 2010. This data will feed into the national reporting requirements under Section 7 i.e. the Department of Health and Social Care is required to publish annual statistics about the use of force in mental health units.

- Section 9 – if a patient dies or suffers serious injury in a mental health unit, the responsible person must consider any relevant guidance relating to investigations of deaths or serious injuries.

- Section 10 – explains that the responsible person may delegate their functions where appropriate to do so.

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

The resources available to inform policies on reducing the use of force typically require a thorough understanding of the data. Some of the resources we expect to see providers using include:

- Safewards

- Towards Safer Services

- Six Core Strategies

- NHS England publish Use of Force dashboard

- Restrictive intervention data dashboard

Legislation

Health and Social Care Act 2012

Health and Social Care Act 2008 (regulated activities) Regulations 2014

Statutory duties

NHS England has published the Accessible Information Standard under the power provided in section 250 of the Health and Social Care Act 2012. NHS England Accessible Information Standard

The following regulations from the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (regulated activities) Regulations 2014 sets out (but not exhaustive) that specifically impact racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities for Trusts to consider:

- Regulation 8: General

- Regulation 9: Person-centred care

- Regulation 10: Dignity and respect

- Regulation 11: Need for consent

- Regulation 12: Safe care and treatment

- Regulation 13: Safeguarding service users from abuse and improper treatment

- Regulation 14: Meeting nutritional and hydration needs

- Regulation 15: Premises and equipment

- Regulation 16: Receiving and acting on complaints

- Regulation 17: Good governance

- Regulation 18: Staffing

- Regulation 19: Fit and proper persons employed

- Regulation 20: Duty of candour

- Regulation 20A: Requirement for providers to display performance assessments (CQC ratings).

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

These resources are available to help support Trusts in complying with the legislation:

Linked to CQC’s well-led domain inspection processes, CQC have published a number of guiding documents to support Trusts and its commissioned partners to describe how providers and managers can meet the regulations:

NHS Act 2006

Statutory duties

Under section 26 of the NHS Act, Trusts have a legal duty to consider the impacts of their decisions on:

- The health and wellbeing of the people of England (including inequalities in that health and wellbeing)

- The quality of services provided or arranged by both them and other relevant bodies (including inequalities in benefits from those services)

- The sustainable and efficient use of resources by both them and other relevant bodies.

Tools/guidance/supplementary documents available

- NHS Providers: A guide to the Health and Care Act 2022 for NHS Trusts

- CQC will review how well Integrated Care Boards, local authorities, NHS providers and other system partners (e.g. those in voluntary, community and social enterprise sector) within an ICS geography are working together to commission and deliver integrated health, public health and social care services.

Statutory duties

The Act introduces new duties that extend the role of the CQC in two areas: integrated care systems and local government adult social care.

Other relevant legislative acts:

Annex B: What good looks like: examples of organisational competencies and self-assessment checklist

Checklist: cultural awareness

- Make sure you understand the diverse needs of the community you serve.

- Co-design culturally appropriate services that reflect the needs of the community you serve.

- Collect and monitor evidence to assess cultural competence and embed improvements that is an anti-racism and anti-oppressive approach, including clinical practices and equality, diversity and inclusion practices across the Trust workforce.

Definition: Cultural awareness is about recognising and understanding the diverse cultural backgrounds of the communities a Trust serves, this should include an awareness of different generational experiences and perspectives, and being sensitive to those in providing care. As a result, care will be more inclusive.

Example

Developing

Trust has set up a working group with ethnically and culturally diverse communities, patients and carers and the community, which maps the diverse needs of the different communities the Trust serves and articulates what culturally specific care and support is needed.

Good

Trust has a good understanding of the diverse population they serve and their cultural needs and offers culturally appropriate services which are co-designed to help meet the Trust’s diverse population. Trusts to have good engagement with community support services including faith groups, leisure clubs and other community assets which will help Trusts to design services that are more holistic and sensitive to cultural beliefs and values.

Outstanding

Trusts take positive steps in routinely evaluating the impact of services. This should include the impact of multi-agency services when individual patients are moved around. Trusts should make concerted efforts to improve services where required. Peer support roles are embedded across all mental health care pathways, and expert by experience roles include focus upon improving the cultural responsiveness of Trust services.

Checklist: staff knowledge and awareness

- Think about how your training standards, your policies and practices support staff to respond to the diverse needs of ethnic communities and make improvements where necessary.

Definition: Staff knowledge and awareness is about recognising and understanding the racialised experiences of the communities a Trust serves and overcoming biases and prejudices by acting upon them.

Example

Developing

Trusts offer equality, equity, diversity and inclusion training.

Good

Trusts have implemented training and support offers to increase staff knowledge and awareness of race inequalities and inequities in mental health care provision, this may include training standards on the history of racism and its psychological impact upon racialised individuals.

Outstanding

Trusts make consistent efforts to keep the profile of race inequalities and inequities in mental health care high within the organisation, ie informal staff networks, and include anti-racism actions to advance race equality and address inequities in staff personal development plans.

Definition: Partnership working is about mental health services working more closely with racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities, leaders and other organisations beyond the NHS, such as ethnic led voluntary/community sector organisations, social care, faith groups and others to support wellness and embed anti-oppressive partnership working.

Example

Developing

Trusts have actively built connections within their local communities which include ethnic led voluntary sector organisations, patients, carers and ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

Good

Ethnic led voluntary sector organisations, patients, carers and ethnically and culturally diverse communities are involved as active members at board level, in service design, testing and developing innovative ways of working and are contributing their expertise.

Outstanding

Trusts evidence tangible power, and resource, redistribution whereby their community partners including ethnic led voluntary sector organisations, support services, and leading community groups share a single vision statement which cuts across organisational boundaries, and the collective impact of each partner’s involvement is routinely monitored and evaluated. This should also include sharing high level data/business information between partners to support preventative strategy developments for service delivery. Each partner is accountable to the key stakeholders for progress in line with the shared vision.

Definition: Co-production is ensuring ethnically, and culturally diverse patients and carers are treated as equal partners in decision making on their care and treatment plans, and actively involved in the design, development and review of care pathways across all ages.

Example

Developing

Racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse patients and carers are consulted when designing and delivering services.

Good

Racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse patients and carers are involved in developing co-productive approaches across the organisation to ensure they promote ways to improve practice.

Outstanding

Racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse patients and carers and their families are fully embedded within the governance structure of the trusts and are co-evaluating care pathways and the impact of systemic racism across all mental health service provision. Racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse patients and carers are supported and empowered to have their say regarding co-produced care and treatment plans, via mechanisms such as peer advocacy and community support.

Definition: A culturally competent and diverse workforce that has a positive impact on patient and carers from racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities; and creates a safe space where the workforce champions inclusive leadership, shares learning, intentionally embeds anti-racism approaches and tracks progress.

Example

Developing

Trusts submit the annual WRES/WDES report as required and show progress against the agreed indicators of workforce equality. It should be noted that WRES and WDES reporting is mandated and that action plans must include initiatives that address all of the reporting indicators which helps to improve Black, Asian and ethnic minority staff experience.

Good

Trusts engage with their ethnically and culturally diverse workforce and draw up plans to bring about equality of outcomes, this may include agreeing at a local level indicator that measure ethnically and culturally diverse staff mental wellbeing. Established alignment with NHS England’s Mental Health Workforce Equity Fellowship Programme and its related workstreams.

Outstanding

Established staff network for ethnically and culturally diverse groups have an active role in informing the trust on the recruitment, retention and career progression of ethnically and culturally diverse staff. Trusts should create safe spaces for staff to speak up and to seek feedback from staff networks on proposals to implement initiatives to improve and ensure evidence of data is collected and discussed across the trusts’ governance level aligned to PCREF Part 1 as well as alignment with NHS England’s Mental Health Workforce Equity Fellowship Programme and its related workstreams.

Definition: Co-learning is a two-way process that strengthens collaborative knowledge sharing beyond co-production principles and focuses on how Trusts can raise awareness of early intervention support amongst racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities and learn more about community concerns and barriers in return.

Example

Developing

Trusts demonstrate co-productive approaches to policy and services are in place (see also ‘Co-production’).

Good

Trusts have identified community champions and/or other approaches to keep abreast of community concerns and barriers to access and good experiences of care and works with local community leaders to ensure referral routes for early support are clearly communicated amongst ethnically and culturally diverse communities.

Outstanding

Trusts equip communities with resources so that local community representatives can be supported to facilitate training and awareness raising amongst staff to instil an understanding and/or learning experience of different cultural approaches and the type of care needed, so staff can support people to access the right care, based on anti-racism and rights-based approaches, at the earliest possible opportunity.

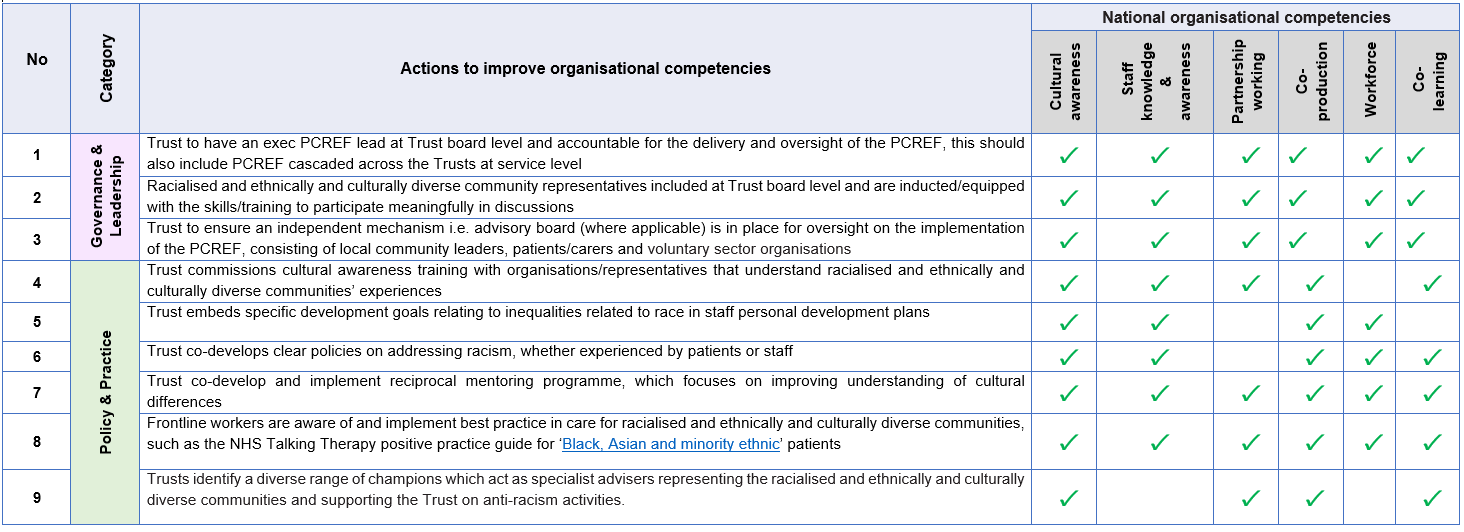

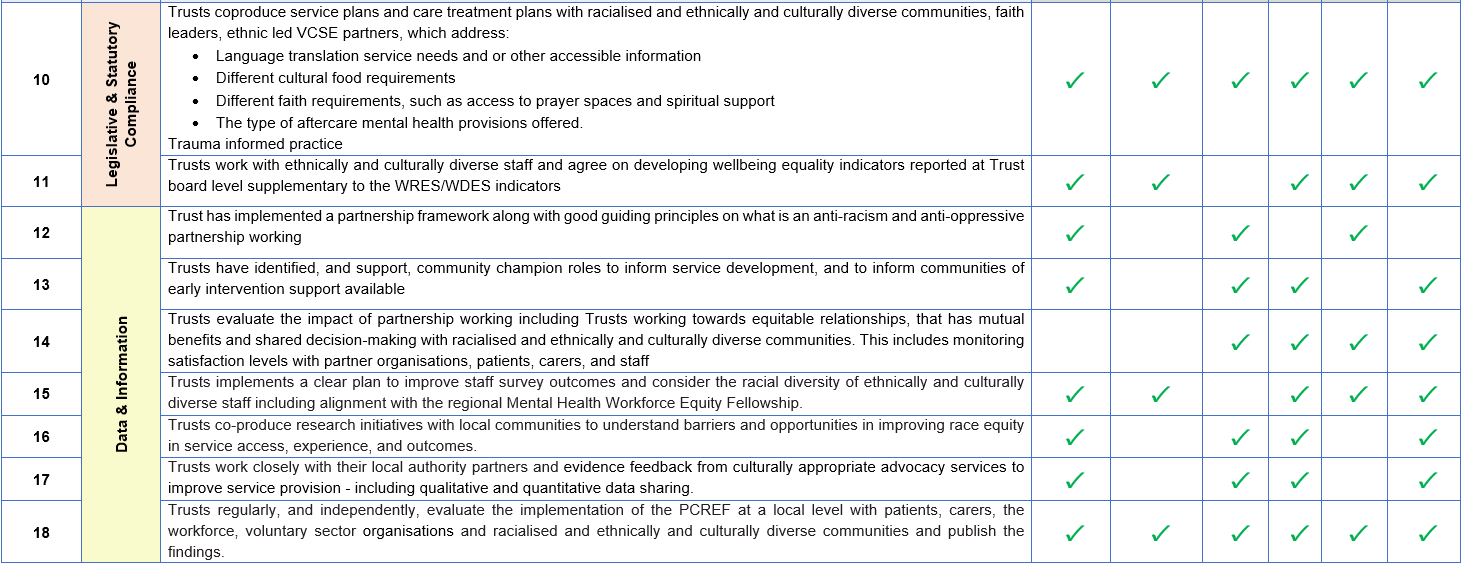

Self–assessment checklist – opportunities to improve the six national organisational competencies have been identified below:

View the above table as word document.

Annex C: Patient and carer experience and outcome measure tools

Patient and carer experience tools

- NHS England – The Friends and Family Test

- Complaints, compliments and safeguarding reports

- Patient and Family centred tool kit (PFCC)

- Experience Base Co-Design tool kit (EBCD)

- CQC Community mental health survey 2022

- Patient Advice and Liaison Service

- Tackling inequalities and Discrimination in health services (TIDES)

- Mental Health Trusts local patient and carer surveys

- Mental Health Trusts staff self-assessment tool

- Feedback from voluntary sector partners

- Experts by experience feedback from patient and carers

- Experience of Service Questionnaire (ESQ) formerly known as CHI-ESQ

Outcomes tools

- Mental Health Outcomes

- NHS England – Patient Reported Outcomes Measures (PROMS)

- Adult Community MH: DIALOG+ | East London NHS Foundation Trust (elft.nhs.uk)

- Adult Community MH: ReQoL: Overview

- Adult Community MH but also widely used in CYP: Goals Based Outcomes

- Children and young people mental health outcomes metric

- Implementing ROMs in Specialist Perinatal MH services

- Talking Therapies Manual

Acknowledgements

Author: Dr Jacqui Dyer, MBE, and NHS England Mental Health Equalities Advisor, Chair for the Advancing Mental Health Equalities Taskforce and the PCREF Steering Group, Jonno Mccutcheon, Deputy Head, Quality and Transformation and Husnara Malik, Programme lead, NHS England National Mental Health programme.

Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust, Roisin Fallon-Williams, CEO, Jaskiern Kaur Associate Director of Equality, Diversity, Inclusion and Organisational Development, Mandy Fletcher, Head of Programmes.

East London Mental Health Foundation Trust, Lorraine Sunduza, CEO and Chief Nurse, and Julianna Ansah, Equality Diversity Lead .

Greater Manchester Mental Health Foundation Trust, Catherine Prescott Head of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion.

South London and Maudsley Mental Health Trust, Zoe Reed, Director of Organisation and Community and Freedom to Speak Up Guardian, Shania Ruddock Deputy Director (PCREF).

Voluntary sector organisations who helped support the development of the PCREF, they are:

- Acacia Family Support

- Black Thrive Global

- Caritas Anchor House

- Catalyst 4 Change

- Change Grow Live

- Citizens Advice (East End)

- Coffee Afrique

- Croydon BME Forum

- Derbyshire Gypsy Liaison Group

- East London Mosque

- Hestia

- Making Connections Work

- Mind in Tower Hamlets and Newham

- Nishkam Healthcare Trust

- The Association of Jamaican Nationals (Birmingham UK)

- The 1928 Institute

PCREF early adopter sites:

- Essex Partnership University Trust

- Gloucestershire Health and Care Foundation Trust

- North East London Foundation Trust

- Oxleas Foundation Trust

- Pennine Foundation Trust

- Sheffield Health and Social Care Foundation Trust

NHS England Advancing Mental Health Equalities Taskforce members

NHS England Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework – Steering Group members

NHS England Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework – Feedback Mechanism Group members

People with lived experience of mental health

Professor Stephanie Hatch, NHS England Chair for Mental Health Data and Research subgroup and Vice Dean for Culture, Diversity and Inclusion and a Professor of Sociology and Epidemiology at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London.

Transformation Partners in Health and Care

Mental Health Voluntary sector partners

Publication reference: PRN00108