Clinical foreword

When someone is so unwell that they need inpatient mental health care, we should be confident they can access it quickly and receive care that is safe, therapeutic, and genuinely helpful.

That’s what brings many of us into this work. But too often, the systems we rely on make it harder than it should be.

As clinicians, we understand what good care looks like.

We also know the frustration of fragmented pathways, unclear responsibilities, and processes that can feel more obstructive than supportive.

For patients and their families, this can feel confusing and distressing. For staff it can be stressful and demoralising. Poorly functioning systems don’t just lead to delays and stress for patients, they wear us down too.

This guide is about improving how care pathways work, so they support good care instead of getting in the way. It brings together practical steps and tested ideas from across the country — many of which will feel familiar.

This isn’t about grand redesigns or headline innovations, but about doing the basics well.

It’s about making sure pathways are joined-up, transitions between services are smooth, every point of contact is helpful and compassionate, and the whole process works reliably for the people who depend on it.

When the system works as it should do, our work can be immensely satisfying.

When care is timely, well-organised, and clearly communicated, patients feel held and supported, and staff feel in control and able to give the care they came into the profession to provide.

We know this is achievable because we see it happening in many places. Our challenge now is to spread that good practice, learn from what’s working, and address the issues when it isn’t.

This guide is a starting point developed from insights from frontline staff and the patients and carers they have worked with on what helps and makes a difference.

A good test of any care system is whether we can explain it to a neighbour and feel confident that if someone they loved needed our care, it would work well.

If we can’t say that yet about the services and places in which we work, then this guide is a good place to start.

Dr Mary Docherty

National Clinical Director for Adult Mental Health, NHS England

Introduction

This improvement guide is for staff involved in planning and improving mental healthcare inpatient flow and the discharge of adult patients from mental health settings (including NHS, local authority, housing and other partners).

It is part of a wider series designed to support staff delivering clinical operational improvement initiatives.

The guide provides suggestions and exemplars for staff involved in patient flow improvements.

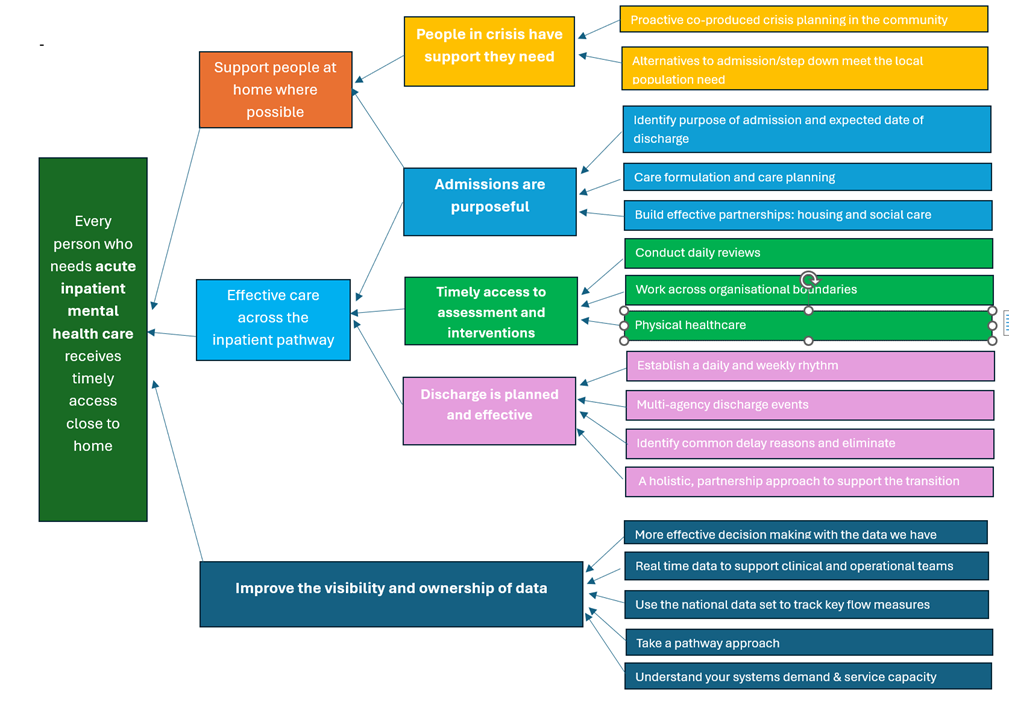

The content is structured around a driver diagram which captures the key drivers of flow and that may impact unwarranted variation in care.

Intelligence and evidence on effective interventions or approaches have been collated along with good practice examples to support organisation and system level improvement activity.

Background

The guide focuses on working age and older persons’ acute mental health inpatient flow as a key enabler to improve clinical effectiveness and patient experience.

Reducing the length of time people require inpatient care – measured by the proxy metric average length of stay – is the overarching focus for elective learning and improvement networks across the country.

Alongside the statutory discharge from mental health settings guidance, significant improvement work is taking place across the acute care pathway, and guidance is available which sets out the vision for acute mental health care, the commissioning arrangements and the culture of care within these services.

It builds upon both the 10 discharge initiatives and the Local Government Association framework to support discharge from mental health inpatient settings.

Over 100 frontline staff, people and families, academics, system leaders, providers, and stakeholders have developed a set of standards which articulate the culture of care across inpatient services now and in the future model.

The Culture Change Improvement programme launched in January 2024 and over the next 2 years (to March 2026) will deliver 6 interventions to 60 providers across England.

We know that achieving a positive workplace culture has benefits for employee engagement and performance, staff retention and a person’s outcomes.

What are we trying to achieve?

Every person who needs acute inpatient mental healthcare receives timely access close to home.

Figure 1 outlines goals for improving mental healthcare, focusing on access to care close at home, supporting people at home, crisis support, purposeful admissions, timely assessments and interventions, and effective discharge planning.

Actions include crisis planning, daily reviews and data-driven decision-making to ensure timely and effective care.

How will we know that the changes are leading to an improvement?

Use of time series data will help determine if actions taken have contributed to statistically significant improvement in the value indicators.

Further resources and guidance designed to support NHS staff to make the best use of their data to inform judgements and decisions for action can be accessed from the NHS England website.

A list of the measures within the Model Health System are included in appendix 1. These are measures trusts should record to monitor and explore how activity including clinical care and clinical operational processes are working.

What should we focus on to make improvements in care and outcomes?

In this section several drivers of timely access to inpatient care are explained and exemplars provided.

Users of this guide should consider which of these may be having the most impact on the care they deliver and prioritise their improvement focus accordingly.

1. People in crisis have the support they need

1.1 Proactive co-produced crisis planning in the community

Crisis plans should be co-produced, and focus on what actions and support are most useful to the person when they begin to experience a crisis.

This can include planning when a person may need to be admitted to the hospital, and identifying what interventions and support are needed during their stay.

Recognising and planning for needs early can support shorter and less restrictive admissions.

Crisis and safety plans should be up to date, visible and easily accessible to out of hours care providers and primary care.

Resources and examples

- Royal College of Psychiatrists core standards for mental health services.

- The Evaluation of the Peterborough Exemplar aimed to assess the effectiveness of a community mental healthcare model improving service accessibility and service users’ experience.

1.2 Alternatives to admission/step down meet the local population need

Gatekeeping of inpatient beds – undertaken by the local Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment (CRHT) teams – enables flow of inpatient care to be managed by the ‘hospital at home’ function.

This enables CRHT to assess which people they can safely manage at home, and which people need to be in hospital according to clinical need.

Some people experiencing a crisis need to be supported somewhere which feels psychologically safe, away from their own home, but may not require a hospital admission.

Assessing local needs to determine how many people could be supported through models like crisis houses – and identifying the types of alternatives to admission that are required to meet population need – is a critical part of system planning.

Resources and examples

- The Retreat is an innovative service that supports people in crisis from across Surrey and Northeast Hampshire. It offers a safe and welcoming short stay environment of between 3-7 nights for adults aged 18 and over. The Retreat can be used to support people who would benefit from continued 24-hour monitoring and as a step-down option following discharge from an inpatient bed.

- Cheshire and Wirral Partnership’s First Response Service improves access to services for people experiencing mental health crisis, and ensures that the right care is provided by the right person in the right place.

2. Effective care across the inpatient pathway

When a person requires care and treatment that cannot be provided in the community, they should receive prompt access to effective care. This care should be close to home so that they can maintain their support networks and community links.

In hospital people should receive timely access to the assessments, interventions, and treatments they need, so that their time in hospital delivers therapeutic benefit.

The RCPsych core inpatient standards that describe expected standards of care in inpatient settings are available on the RCPsych website.

2.1 Identify purpose of admission and an expected date of discharge

The purpose of admission should describe the specific assessments and interventions required, anticipated length of stay, and expected date of discharge.

These should be agreed collaboratively at the earliest opportunity with:

- the person accessing the service

- their families and carers

- the inpatient multidisciplinary team

- community team

- CRHT

The expected date of discharge (EDD) is an essential care co-ordination tool that helps teams, people and services prepare for the transition between care settings. It is an estimate, but should be the best informed one possible.

There will be occasions where there is a gap between the EDD and the actual discharge date. The improvement opportunity here lies in accurate date stamps of these 2 measures.

Once captured, the data can be aggregated and analysed to understand why the difference is occurring. The reasons identified can then be used to drive local improvements.

Resources and examples

- Further detail on EDDs and implementation support can be found via the GIRFT website.

- The EDD process should be used to articulate and make explicit what is expected from the admission.

- RCPsych core standards for mental health services.

2.2 Complete care formulation and care planning

This is the opportunity to create the goals for the admission and identify and address any barriers to discharge.

A formulation review should take place within 72 hours of admission to understand and plan the support and interventions that an individual needs to meet their purpose of admission.

A care plan should then be co-produced with the person and their chosen carer (or carers).

Care plans should draw on all forms of documented support, treatment intentions and preferences relating to the person including crisis plans, discharge and recovery plans. They should be started at the earliest opportunity with the person.

Agreed goals help everyone track progress and identify any which are not progressing in a timely way.

Resources and examples

- More information on care formulation and planning can be accessed on the NHS England website.

- More information on manging transitions can be accessed via the NICE website.

- Principles for better partnership working can be accessed at the local government website.

2.3 Build effective partnerships with housing and social care providers

Nationally, over 40% of discharges are delayed because of the lack of available housing at the point of discharge.

Early engagement to secure, sustain and support existing home networks should take place throughout the inpatient stay to prevent housing crisis or delays to discharge.

This should include what support mental health services can offer to housing and support providers and family, friends and carers.

Co-commissioning roles – such as housing co-ordinators and benefits advisors – with the local authority and housing providers can help improve discharge processes and care outcomes.

Some systems have embedded housing officers within inpatient units. This can speed up decision-making and help develop solutions to any housing-related barriers at an early stage.

Resources and examples

- The Local Government Association have produced a framework to support a partnership approach to discharge from mental health inpatient settings.

- This report – available via the housing.org.uk website – draws on a series of case studies to showcase how the NHS and supported housing providers are working together to remove barriers to finding a safe home, and support people leaving hospital at the right time for their recovery.

3. Timely access to assessments and interventions

3.1 Conduct daily reviews

Conducting daily reviews and using systems such as the ‘red-to-green’ approach, helps ensure each day is adding therapeutic benefit for the person and is in line with the purpose of admission.

Effective implementation of this type of approach requires attention to ensure it does not become a performance management tool.

There can be lots of good reasons why something was not done in a busy acute environment when needs and priorities regularly change. The system is there to keep people on track and help reallocate and follow through on actions.

Resources and examples

3.2 Working across organisational boundaries

Peer support and 3rd sector partnerships can be very effective in helping the ward deliver effective and therapeutic care, and in preparing people for discharge and return to the community.

Roles linking into the community and wider voluntary, community, faith and social enterprise offers can be commissioned as an integrated part of the ward multidisciplinary team.

These partnerships can increase access to and uptake of post-discharge support, such as support with daily living, physical activity, relationships, work, education and training and other opportunities to improve health and wellbeing.

Working across organisational boundaries requires a different approach to addressing service gaps to create innovative models of care and should include primary care.

There are examples where GPs embedded in community services and inpatient wards have demonstrated improved outcomes.

The use of trusted assessment when agreed by system partners can also support working across organisational boundaries.

The ‘trusted approach’ method is an initiative to reduce the number of delayed discharges. The underlying principle here is promoting safe and timely discharges between services.

Resources and examples

- The Evaluation of the Peterborough Exemplar aimed to assess the effectiveness of a community mental healthcare model improving service accessibility and service users’ experience.

- Care Quality Commission guidance on trusted assessors.

3.3 Physical healthcare

The physical health disparities facing people living with mental health conditions are extremely well known.

The mental health inpatient setting provides an opportunity to serve as a safety net; to intervene in the physical health of a group of people who are at risk of poor health outcomes, but who are not engaged with primary care.

Physical health needs can also serve as a constraint to flow creating challenges when physical healthcare needs cannot be met by existing arrangements.

Understanding the current quality of provision and how it can be improved is critical to making a change in this area.

Having systems and agreement for collaboration across partners such as primary care and acute care can help minimise these delays and improve the quality of care.

Making sure the clinical workforce planning meets the requirements of the setting and addresses common gaps in provision. This may include primary care and allied health professionals.

Resources and examples

- This NCEPOD Physical Health in Mental Hospital’s report provides recommendations and implementation aids to help wards and organisations improve the quality of physical healthcare provided to adult patients admitted to a mental health inpatient setting.

- RCPsych core standards for mental health services.

4. Discharge is planned and effective

4.1 Step 1: Establish daily and weekly rhythms

Clinical and operational leadership teams should establish a daily and weekly rhythm. Effective flow and clinically effective care relies on people and relationships at every level across organisations.

Regular communication with partners is a key part of maintaining flow through the system to ensure people get the right care at the right time.

Daily rhythm

Daily actions should follow those outlined in level 1 of the operational pressure escalation level (OPEL) framework agreed by your system.

An example may look like this:

| 9.00am | Update wards and consultants on current bed states, admissions and discharges over previous 24 hours |

| 9.30am | Daily patient flow huddle – additional huddles as outlined in the OPEL framework |

| 9.30am+ | Daily patient reviews by senior decision makers |

| 11.00am | Detailed bed state issued to key partners and internal contacts |

| 11.30am | Update system partners |

| 2.00pm | Daily patient flow huddle (aligned to level of escalation) |

Weekly rhythm

Clinical discharge meeting – partners supporting routine discharges

Clinical Ready for Discharge meeting – partners supporting complex discharges

Resources and examples

4.2 Step 2: Plan multi-agency discharge events

Multi-agency discharge events (MaDEs) are events with key partners held on a regular basis, to review complex cases.

The key to effective MaDEs is ensuring you have the right people in the discussion with right seniority and authority for decision-making and escalation.

Resources and examples

- Camden and Islington share their experience of setting up MaDEs within their trust (YouTube)

- Further MaDE guidance (FutureNHS login required)

4.3 Step 3: Identify common reasons for delay and work together to eliminate them

Use the clinically ready for discharge (CRFD) data and MaDE data to identify common reasons (and consider solutions) for people being delayed in hospital; for example, housing support or accommodation.

Start by reviewing:

- those who are occupying beds while clinically ready for discharge

- adults and older adults with a long length of stay (over 60 days for adults, 90 days for older adult admissions)

Each person’s journey should be critically reviewed to understand what next steps are required to reach safe discharge, and to make sure critical interventions happen without delay.

Resources and examples

4.4 Step 4: Support and transition

Post-discharge follow-up with the patient is carried out (by the community mental health team, or crisis resolution and home treatment team) at the earliest opportunity – within a maximum of 72 hours of discharge – to ensure the right discharge support is in place.

This first contact is to ensure the aftercare plan is in place and happening without immediately breaking down for any reason.

It is critical that the person(s) doing this initial visit is aware of:

- the known early relapse warning signs for that person

- if relapse occurs, what usually does or does not work for that person

- what harms may emerge for that person in relapse – and how quickly they may emerge

Also critical in this period is professional curiosity: particularly to explore if any issues are arising in this early transition that may increase the likelihood of relapse occurring.

It may take several weeks to see if the plan is delivering intended benefits or whether changes are needed.

How many visits the person will need, and from whom, becomes modified as necessary following the initial community visit; using clinical judgement and co-working with the person and their support network.

It is essential that organisations have a clear system to record, monitor, review and act on any discharge that occurs without 48 hours of prior notification to the person, the inpatient team and those involved in the community plan.

Regular review of these events should be a key part of governance of the inpatient flow system.

Robust adherence to policies and processes regarding prescribing and dispensing of medication at the point of, and period after, discharge are essential for patient safety.

Proactively establishing clear pathways and processes for medication management that are agreed by partners can help eliminate delays.

Recent guidance may identify opportunities to improve this interface between mental health providers, primary care and community pharmacies.

Resources and examples

- An example on how Mersey Care have implemented their PRISM model for 48/72 hour follow up can be accessed on the FutureNHS site (FutureNHS login required)

- The NHS England website has information on the role and use of community pharmacy in this area

- Royal College of General Practitioners guidance on the primary and secondary care interface

- HAY Peterborough is a website that brings together everything in the local area that is good for wellbeing and helps people connect with these activities

5. Data visibility and ownership

Mental health systems need to have well-developed processes and procedures to capture relevant data, improve its quality, monitor and appropriately use key metrics associated with efficient and effective delivering of inpatient services.

Many of these metrics are already available. It is important that hospitals use the data and ‘measurement for improvement’ principles to support ambitions to localise inpatient care over the next 3 years.

5.1 More effective clinical and operational decision making with the data we have

The data the mental health system generates should be used to identify opportunities to strengthen partnerships and improve care effectiveness, efficiency and productivity.

Being able to spot trends early on can lead to more productive and proactive questioning at an early stage that helps support improvement rather than monitoring performance against targets.

The trends identified in the data need to be joined up with clinical and operational system conversations.

Without this approach there is a risk that events – for example, mental health waits in ED – are viewed in isolation which can lead to focus on the wrong solutions that address symptoms rather than causes of challenges with flow.

Resources and examples

- Making data count: these practical guides are suitable for those working at all levels in the NHS, from ward to board, and will show you how to make better use of your data.

5.2 Real time data to support clinical and operational teams

Clinical and operational teams should have data visible and easily accessible to them so that data-driven working becomes embedded within teams and their day-to-day processes.

This could be achieved by optimising your Electronic Patient Record (EPR) system, for example through the use of mobile staff apps, to make the information staff need to view and input easily accessible.

Ensuring staff also have educational supports to build confidence with looking at data is key.

Operational and executive leaders setting the standard and daily discipline of what’s expected of everyone throughout the system helps implementation of this approach.

Having regular touchpoints to monitor progress against agreed actions aligned to the real time data agreed with system partners helps system working and better identification of challenges and the right actions to address them.

Transparency and using common language help to avoid any ambiguity and build collaborative approaches to problem solving.

Resources and examples

- Digital systems that sit alongside the core EPR can support staff operationally and embed data-rich processes, for example:

- The FutureNHS website (FutureNHS account and login required) hosts a discovery report that has identified good practice examples

- A set of practical resources is also available on FutureNHS (account/login required), aligned to 8 criteria for success, to support with the effective implementation of digital technologies in mental health services

5.3 Use the national data set to track key flow measures

Data visibility is an area frequently cited as a challenge across providers, commissioners and partners in the mental health system.

A suite of metrics, dashboards and benchmarking to support productivity and performance improvements will be linked to this and other improvement guides to help overcome these challenges.

These will be housed alongside UEC and elective measures in the model health system.

Resources and examples

- The Model Health System is a data-driven improvement tool that enables NHS health systems and trusts to benchmark quality and productivity. By identifying opportunities for improvement, the Model Health System empowers NHS teams to continuously improve care for people in it services. Guidance on access is available at the NHS England website.

5.4 Take a pathway system approach

The system must always put the person at the centre of any process.

High-level single metrics such as delays to discharge or average length of stay are influenced by multiple factors. Solutions are not always within the gift of inpatient teams.

Using a collection of metrics across the acute system pathway will help identify barriers and where improvements should be prioritised.

Each system partner will have insights into different issues and how to fix them. Bringing these perspectives together in a collaborative approach is key to working effectively at a pathway improvement level.

Taking a whole system pathway approach is about developing a shared understanding of the system-level issues using the data and valuing each other’s viewpoints.

To reach a system view, the visibility of an agreed set of data is required across partners and data sharing based on a single version of the truth is integral to this approach.

Having a system dashboard can improve trust, create a sense of a shared purpose and identify further system opportunities for improvements. It can also help improve data quality and the trust clinicians have in the information shared with them.

Empowering clinical and operational teams with visibility and ownership of data, and aligning that data with ward-to-board data flows and dashboards, can embed a shared understanding of improvement opportunities and provide clinical and operational leaders with the confidence in using data to inform discussions.

Resources and examples

- Information governance is often perceived as an reason why data cannot be shared. NHS England guidance will support you to use and share information with confidence when caring for patients and service users.

- Data from patient health and adult social care records helps us to improve individual care, speed up diagnosis, plan local services, research new treatments, and ultimately, save lives. Ensuring that staff and patients have access to the right data, at the right time, is vital to the NHS providing effective, safe, good value services. Further guidance can be accessed at the NHS England website.

- The Evaluation of the Peterborough Exemplar aimed to assess the effectiveness of a community mental healthcare model improving service accessibility and service users’ experience.

5.5 Understand your system’s demand and service capacity

The mismatch between demand and capacity is one of the main reasons why waiting lists or backlogs develop and waiting times increase.

Understanding demand across the whole pathway includes community-based crisis resolution and home treatment teams, approved mental health professionals service, mental health social care, enablement, housing, and primary care, education and others.

Understanding of different the demands across key partnerships should underpin clinical and operational leadership decision discussions and decision making.

Being able to plan and understand the competing demands on different services facilitates a more transparent approach to managing risk and helps identify better solutions.

Understanding the service capacity required to respond and manage demand safely and effectively will put a spotlight on any gaps between the demand and capacity.

Beds are not capacity; they are waiting areas for therapeutic interventions to happen. Bottlenecks occur if we use flawed assumptions in our service modelling. The workforce required to deliver the therapeutic input is a critical measure within this process.

5.6 Use workforce modelling principles to apply 7-day working

An essential part of understanding capacity is workforce profiling across 7 days across the pathway.

Allied health professionals have a key role to play in delivering therapeutic interventions within the inpatient setting, but are often overlooked in the planning of services.

All parts of the pathway play a part in enabling people who are clinically ready for discharge to be discharged over weekends and bank holidays and allow people who require admission timely access to local beds.

Resources and examples

- The Mental health optimal staffing tool (MHOST) calculates clinical staffing requirements in mental health wards based on patients’ needs which, together with professional judgement, guides chief nurses and ward based clinical staff in their safe staffing decisions.

- Several resources to support your learning and development as well as free tom access tools are available at the NHS England website.

- BMJ Quality & Safety: Developing the allied health professionals workforce within mental health, learning disability and autism inpatient services: rapid review of learning from quality and safety incidents.

- The RCPSych core standards for inpatient care describe key standards for delivering therapeutic interventions over 7 days.

Please share your ideas and feedback

Thank you for engaging with this guide. While we have collected a wide range of improvement ideas, we want to gather your local improvement ideas for inclusion in an updated version of this guide.

Please share your ideas and feedback with us. There are 2 ways you can do this:

- by emailing us at england.improvementdelivery@nhs.net

- by feeding back through your local Learning and Improvement Network; details on the networks are on the FutureNHS Platform (FutureNHS account and login required)

Appendix 1. National measurement

Value indicators:

- Average length of stay for adult mental health patients in acute adult mental health beds (adult, older adult and PICU)

- 12 hour + stays in emergency department for people with a mental health condition (adult)

- Adult acute mental health inappropriate out of area placements active at the end of the month

Tracking indicators:

- Number and percentage of admissions involving people crisis intervention or home treatment not known to services.

- Percentage of people on community health caseloads who are admitted to hospital.

- Adult and older adult mental health bed occupancy.

- Number of people who are clinically ready for discharge who are occupying inpatient beds.

- Long length of stay (60 day+) for adult mental health inpatients.

- Long length of stay (90+) for older adult acute mental health inpatients.

- Discharges and follow-up within 72 hours.

Publication reference: PRN01976