Summary

In 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan was published, together with the NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan, which set out ambitious, funded plans, to transform mental health services. Shortly after this, the COVID-19 pandemic began, which had a major impact across the health system, including mental health services. As a result of pandemic pressures and the increases in cost of living currently facing households, inpatient mental health services have experienced sustained rises in demand and acuity, which have been particularly challenging due to the current workforce pressures across the NHS.

While adult and older adult acute inpatient mental health teams continue to work hard to deliver high quality care in line with the commitments set out in the NHS Long Term Plan and NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan, feedback from those who work in and access these services indicates that while some people have positive experiences, others can experience issues accessing care that truly meets their needs and supports their recovery. This can include delays to accessing inpatient care and to being discharged, people being placed out of area where it can be challenging for friends and family to visit and disproportionate use of restrictive interventions. Furthermore, issues with the quality of care disproportionately affect certain groups of people, including people from ethnic minorities, people who have a learning disability, and autistic people.

It is vital that every person who needs acute inpatient mental health care receives timely access to high quality, therapeutic inpatient care, close to home and in the least restrictive setting possible. To support this, NHS England has produced this guidance to set out its vision for effective care in adult and older adult acute inpatient mental health services, together with resources and suggestions to support delivery. In this vision:

- Care is personalised to people’s individual needs, and mental health professionals work in partnership with people to provide choices about their care and treatment, and to reach shared decisions.

- Admissions are timely and purposeful – When a person requires care and treatment that can only be provided in a mental health inpatient setting and cannot be provided in the community, they receive prompt access to the best hospital provision available for their needs, which is close to home, so that they can maintain their support networks and community links. The purpose of the admission is clear to the person, their carers, the inpatient team and any supporting services.

- Hospital stays are therapeutic – People receive timely access to the assessments, interventions and treatments that they need, so that their time in hospital delivers therapeutic benefit. Care should be delivered in a therapeutic environment and in a way that is trauma-informed, working with people to understand any traumatic experiences they have had, and how these can be supported in hospital, in a way that minimises retraumatisation.

- Discharge is timely and effective – People are discharged to a less restrictive setting as soon as their purpose of admission is met and they no longer require care and treatment that can only be provided in hospital. For this to happen, there needs to be discharge planning from the very start of a person’s admission. There also needs to be a range of community support available and supported living options which meet different needs and enable people to maintain their wellbeing and live as independently as possible after discharge.

- Care is joined up across the health and care system – inpatient services work in a cohesive way with partner organisations, at admission, during a person’s inpatient stay and to support an effective discharge, so that people are supported to stay well when they leave hospital.

- Services actively identify and address inequalities that exist within their local inpatient pathway, in partnership with people from affected groups and communities. This must include ensuring that people are not prevented from accessing or receiving good quality acute mental health inpatient care simply because of a disability, diagnostic label or any other protected characteristic.

- Services grow and develop the acute inpatient mental health workforce in line with national workforce profiles, so that inpatient services can offer a full range of multi-disciplinary interventions and treatment. Staff wellbeing, training and development should be supported, so that inpatient services are a great place to work and staff are enabled to offer compassionate, high quality care.

- There is continuous improvement of the inpatient pathway – services strive to improve by making the best use of data, regularly developing, testing and refining change ideas using quality improvement methodology, and ensuring that service improvements are co-produced with people with experience of inpatient services and their carers.

We know that across the country there are services already delivering care that meets a number of these aims. With both the substantial investment in mental health services as part of the NHS Long Term Plan, the Government setting out its intention to reform the Mental Health Act (MHA) in the draft Mental Health Bill, and the recent establishment of NHS England’s Mental Health, Learning Disability and Autism Inpatient Quality Transformation Programme, now presents a significant opportunity to ensure that across all elements of this guidance, services are delivering care that is of a standard that we would all be proud of, and always puts people accessing services and those close to them at its heart.

Some perspectives on what good quality care means to people who have personal experience of acute mental health inpatient care, either directly or as a carer, are illustrated by these quotes:

“I would like to have staff on the ward who are compassionate and engaged, who understand my whole holistic and individual needs, and provide therapies and various activities that are meaningful, helpful, are of interest to me, and which feel comfortable for me to do. They should also help me to get better and plan my aftercare so that I can manage when I leave hospital.”

“For me, ideal inpatient care is when staff are willing to meet me and my loved ones where we are at each day, without expectations or demands. It’s about the service understanding how the small and large decisions that they make can impact my relative and her wider network, and the service being willing to work with us to identify and achieve the best outcomes for my relative, understanding that her needs change and fluctuate.”

“Co-production needs to be at the heart of inpatient care. I want to see clinicians and professionals working with me and my carers as equal partners, to develop, deliver and keep under review the best possible inpatient care for my needs. I want to see mental health inequality addressed, through people with lived experience supporting services to meet the needs of people from diverse communities.”

“If I need to be admitted, I would like inpatient care that is person-centred and provided in a recovery-focused environment. My admission should be as short as possible so as to not cause unnecessary trauma and there need to be more places that I can go to if I can’t go straight home when I’m ready to leave hospital. The power structures in inpatient settings also have to change, so that power is shared with people on the ward, particularly when they are from a marginalised group.”

Purpose of this guidance

This is the first time that NHS England has published national policy guidance outlining its vision for inpatient mental health care for adults and older adults, including people who also have dementia, an alcohol or drug problem, a learning disability, autism and any other individual needs. The guidance is intended to support integrated care systems (ICSs) and providers of mental health acute wards and psychiatric intensive care units (PICUs) to meet the ambitions for acute mental health care set out in the NHS Long Term Plan and NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan, alongside existing legislation and acute mental health standards (see Appendix 1).

It is hoped that this document will support partnership working between inpatient mental health services and crisis resolution home treatment teams (CRHTTs), community-based mental health and learning disability teams, and other services, including social care providers, local authorities, independent sector providers and voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector organisations.

The guidance has been developed in partnership with frontline clinicians and people who have lived experience of accessing inpatient services, either directly or as a carer (see contributors to this guidance).

Key NHS Long Term Plan commitments for adult acute mental health inpatient services:

- Eliminate all inappropriate adult acute mental health out of area placements (a definition of these can be found on the FutureNHS platform (requires login).

- Improve the therapeutic offer from inpatient mental health services by enhancing access to therapeutic interventions and activities.

- Increase the level and mix of staff on acute mental health inpatient wards, including improving access to peer support workers, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, housing experts and other relevant professionals during admission.

- Reduce avoidable long lengths of stay in adult acute mental health inpatient settings (including for people with a learning disability and autism), so that people are not staying in hospital any longer than necessary.

- Reduce the number of people with a learning disability and autistic people in mental health inpatient settings, so that by March 2024, there are no more than 30 adults with a learning disability and/or autism in an inpatient setting, per one million adults.

- Ensure that all inpatient care commissioned by the NHS meets the Learning Disability Improvement Standards.

- Further information on several of these commitments can be found in the NHS Mental Health Implementation Plan 2019/20 – 2023/24. Across the delivery of all of these commitments, consideration must be given to reducing the associated inequalities, involving people in decisions about their care and adapting interventions and activities to meet individual needs and preferences.

Key elements of the inpatient pathway

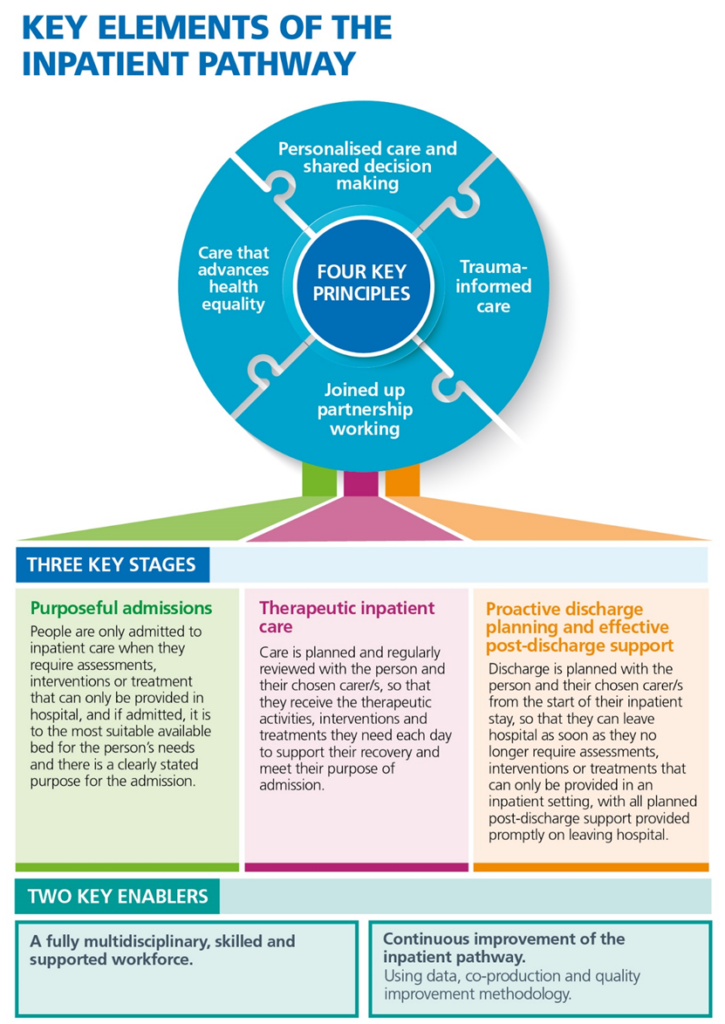

The diagram on the following page illustrates the key elements that underpin effective acute mental health inpatient care. It is made up of four key principles, three key stages and two key enablers.

The three key stages relate to pre-admission, during the hospital stay and discharge, while the four key principles and the two key enablers apply across the inpatient pathway. Below this diagram, there is also a brief memorandum of the key actions that need to be taken within 72 hours of a person’s admission to hospital. Further detail on each of the components of the diagram can be found in the sections of the guidance that follow; a summary is also provided in Appendix 2.

Key actions that need to have taken place within 72 hours of admission:

- Person’s electronic patient record (EPR) reviewed (including identifying any recorded advance choices and reasonable adjustments required); checking back key information from the person’s EPR with them and their chosen carer/s and noting any changes/updates.

- Holistic assessment completed and uploaded to the person’s EPR.

- Purpose of admission statement and estimated discharge date (EDD) agreed with the person and their chosen carer/s and uploaded to the person’s EPR.

- Interventions and treatment for physical and mental health conditions commenced/maintained, and a physical health check completed.

- Formulation review completed and care planning begun.

- Discharge planning begun – identifying what needs to happen for discharge to occur.

Please note, the term chosen carer/s is used throughout this guidance to indicate that the person should be able to choose who to involve in their care, which may include friends as well as family, and could change over time. For people detained under the MHA, there are additional processes related to a person’s Nearest Relative, which must be followed. (NB this may change if and when the draft Mental Health Bill is passed into law, including the term changing to Nominated Person.)

Principles of effective inpatient care

This section explains the four key principles that are at the heart of good inpatient care. These principles should underpin the delivery of care across a person’s entire experience of the inpatient pathway, which begins pre-admission and includes the planning and facilitation of access to effective post-discharge support. In addition to these principles, all services need to be delivered in line with other guidelines, care standards and legislation (see Appendix 1 for details), including the, Equality Act (2010), Human Rights Act (1998), Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act (2018), the Mental Health Act (1983) (MHA) and the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA).

Personalised care, including shared decision-making

Personalised care involves supporting a person in a way that takes account of their preferences, meets individual needs (including any reasonable adjustments required), enables the person to realise their aspirations, and draws on the person’s strengths. NHS England’s model for personalised care can be accessed on the NHS England website.

Delivering personalised care requires those providing inpatient mental health care to work as equal partners with the person and their chosen carer/s to reach shared decisions about the next steps in the person’s care. It also involves recognising that even when in crisis or acutely unwell, people are experts in their own lives and have valuable contributions to make about the support that they need both before, during and after their hospital stay. This approach to personalised care is illustrated in the extract below, which was developed by lived experience members of NHS England’s Adult Mental Health Advisory Network:

“…if we are going to truly change things for the better, we need to think about people as a whole – what makes up their lives, and their needs, wants and ambitions…These varied and personal needs must be reflected in the support and treatment we receive from public services too.

Here we should be striving for needs based, not diagnosis-based care and treatment…we also need to empower and enable clinicians to work with us to understand our needs as a whole person before agreeing a course of actions to keep us well. We need choice and to practice shared decision-making.” Published in the Department of Health and Social Care’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Plan: Discussion Paper.

Here are some steps that can be taken to support every person in inpatient settings to receive personalised care, which empowers them to make choices about their care and aids their recovery:

- Ensure that the assessment and care planning process is holistic (see further information in the care planning section and Appendix 3) and covers the person’s needs, strengths and aspirations. Assumptions about a person’s needs, preferences or abilities should not be made based on a disability, diagnostic label or protected characteristic.

- As far as possible, follow any advance choices that a person has made, which outline their preferences for future care and treatment. Any deviations from a person’s advance choices need to be clearly explained to the person and/or their chosen carer/s, and recorded.

- Ask the person who is best placed to act as their chosen carer/s and to contribute to discussions about their needs, wishes and aspirations – bearing in mind this may not always be a relative.

- Explore and record the person’s preferences as to what aspects of their care they would like their chosen carer/s involved and the types of information they would like to be shared with their chosen carer/s (and explain the circumstances in which their preferences may not be followed – see pages 78-82 of the MHA Code of Practice for further information (which includes information on confidentiality whether people are or are not detained in hospital)

- Check with the person’s chosen carer/s that they are comfortable taking on this role and provide them with information about sources of support for carers.

- In cases where a person does not want certain individuals (eg family members) involved in their care, or for information to be shared with them, this must be respected (within the limits of legislation – see link to the code of practice above for further information). However, these family members should still be given general information about what to expect from inpatient care and the opportunity to discuss their views about the person’s needs.

- Ask the person and their chosen carer/s about their communication preferences and identify how these preferences will be met while the person is in hospital, to ensure that people fully understand their rights (including rights under the MHA) and are able to play an active role in their care and discharge planning. For example, this may involve providing access to interpreters, providing information in a range of formats (eg in translation, large print, Braille and Easy Read format, using Augmentative and Alternative Communication, and using video clips and visual diagrams to aid understanding.

- Further information on the requirements for organisations providing NHS care and/or publicly-funded adult social care to make health and social care information accessible, can be found here: Accessible Information Standard.

- Make it part of ward practice to ask people their preferences, offer them choices about their care and treatment, and regularly check with the person about whether their current care plan is working for them. If the person says that further support is needed to help them to recover, take active steps to put this support in place. Where a person is detained under the MHA or lacks mental capacity to make specific decisions according to the MCA, it may be necessary to make some decisions on the person’s behalf, following processes in the relevant legislation. However, there should continue to be a focus on seeking to elicit people’s wishes and preferences and giving people as much choice as possible about their care and treatment.

- Make sure people have access to and are supported to meet with independent advocates (including as required under the MHA/MCA) and peer support workers/lived experience practitioners, with a diverse range of experiences and appropriate cultural competency. Ensure that people are aware that they can speak to advocates/peer support workers/lived experience practitioners to gain more information about their rights, how the mental health system works, and for support with communicating their needs, wishes and aspirations.

- Do not use blanket restrictions – rules that are applied to everyone regardless of individual risk. Decisions should be made on an individual basis as far as possible. Where there are limits imposed by national restrictions, organisational policy or individual risk assessments, staff members should creatively explore ways of meeting the person’s needs and wishes, while still adhering to policies and risk assessments.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has produced useful guidance on shared decision-making and advocacy.

Care that advances health equality

The NHS is committed to ensuring that everyone receives high quality health care, regardless of their background. There is also a legal duty to advance equality, diversity and inclusion for everyone accessing health services, as laid out in the Equality Act, including meeting reasonable adjustments. NHS England has set out its plan to deliver more equitable access, experience and outcomes in mental health services in its Advancing Mental Health Equalities Strategy. As part of this, a Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF), to improve experiences of mental health services among racialised and ethnically and culturally diverse communities, has been developed and is beingrolled out for implementation in 2023.

At present, there are significant health inequalities experienced by people in terms of their access to, experience of, and outcomes from acute inpatient mental health services and it is vital that action is taken at all levels to protect and advance health equality. A wide range of groups may experience inequalities in inpatient mental health services. ICSs and providers of inpatient mental health services are expected to use data and intelligence (including national data sets such as the National Mental Health, Dementia and Neurology Intelligence Network and the dashboards linked in this guidance, as well as local intelligence from people with lived experience and complaints data) to identify and monitor groups within their local population who have poorer access, experience, and outcomes from care. A co-production approach should be used to work with these communities to make tangible progress in reducing identified health inequalities.

To support progress in advancing health equality, the following sections provide some ideas on how to enhance the support that is provided to specific groups. These groups have been given additional focus in this guidance based on national-level evidence about the inequalities that they face and information available about some of the actions that can be taken to support these groups in inpatient mental health services. NHS England is however committed to developing further resources to support systems to address the wider inequalities that exist.

When reading the following information, it is important to recognise that people’s identities and experiences are multifaceted, and that being a member of multiple groups that experience inequalities may compound poorer experiences of care. Group-level considerations should therefore always be applied in the context of seeing and treating people as individuals, and working with people to put in place personalised care.

People from racialised and ethnic minority communities

People from racialised and ethnic minority backgrounds experience systemic barriers to accessing care and receiving inpatient support that meets their needs. In developing some suggestions to improve the care offered to people from racialised and ethnic minority communities, it is acknowledged that this term encompasses a wide range of people with very different cultural backgrounds and identities. These suggestions are therefore general, with the underpinning aim to centre care on people’s individual needs in relation to their race, ethnicity and culture:

- At admission, ask people and their chosen carer/s about how they understand their mental health condition, and plan with them how their cultural, religious, and spiritual needs (including associated dietary preferences) can be best supported while they are in hospital. Check in regularly to find out if these needs are being met.

- Provide key information in different languages and ensure ready access to independent interpreters (instead of relying on family members to translate).

- Provide access to culturally appropriate advocates and peer support workers/lived experience practitioners that reflect racialised and ethnic minority communities, as well as specialist input from VCSE sector organisations and faith-based groups.

- Ensure there are clear routes for reporting racism and discrimination, originating either other people on the ward or staff, as well as for accessing support when racist or discriminatory behaviour is experienced.

- Provide training to support staff to develop their cultural competency and the skills needed to plan and deliver care in a way that is culturally appropriate and does not make assumptions about people’s needs based on their appearance or characteristics.

- Monitor key metrics (eg length of stay, rates of detention) by ethnicity and collect feedback on people’s experiences of care and use this information to inform action to improve the cultural appropriateness of care.

- Embed the changes outlined in the Patient and Carer Race Equality Framework (PCREF) across all aspects of policy, procedure and practice.

People with a learning disability and autistic people

People with a learning disability and autistic people may experience inpatient care that is not adjusted to their needs and they are also disproportionately more likely to experience restrictive interventions while in hospital. For these reasons, the NHS Long Term Plan made a commitment to reduce the number of people with a learning disability and autistic people in mental health inpatient settings by the end of 2023/24 and work is also underway to reduce long-term segregation and restrictive practice.

To improve the support that people with a learning disability and autistic people receive:

- Ensure that people who are at risk of admission are included on local Dynamic Support Registers and that they have a Care (Education) and Treatment Review (C(E)TR) in the community pre-admission (or if this is not possible, within 28 days of admission) and that the findings of the C(E)TR inform care planning and delivery.

- Work with the person and their chosen carer/s to understand the person’s individual needs and traits, including those relating to communication, interaction, routine, repetition, predictability, food, the sensory environment and any activities or objects that will help their wellbeing. Identify and action the reasonable adjustments that are needed (working with specialist learning disability and autism professionals and other duly qualified professionals, as required) and record key preferences as an alert on the person’s EPR. If someone has a Hospital Passport, this should also be used to inform communication with the person and the support they are offered.

- (Particularly for autistic people) Make adaptations to the ward environment to create low sensory areas (eg using quiet door closers, replacing overhead fluorescent lights and fitting dimmer switches). See this resource pack from NHS England and these principles from the National Development Team for Inclusion (NDTi) for more information.

- Ensure that for all people aged up to 25 who have an Education, Health and Care (EHC) Plan, it is followed as far as possible during the person’s hospital admission and as part of discharge planning, and updated where necessary.

- Ensure all staff working in services registered with the CQC have attended mandatory training on learning disability and autism that is appropriate to their role, in line with the Health and Care Act (2022).

- (Particularly for autistic people) Use the Green Light Toolkit to regularly audit the service and use the toolkit’s resources to improve care for autistic people.

Useful resources include:

- NHS England’s Learning Disability Improvement Standards which support NHS trusts to measure and improve the quality of care they provide to people with a learning disability and autistic people.

- The Health Equality Framework, which supports services to measure their effectiveness in terms of addressing the inequalities experienced by people with a learning disability.

- The national service model for people with a learning disability and autistic people who display behaviour that challenges and guidance to support the implementation of the model.

People with a co-occurring alcohol and/or drug problem

Alcohol and drug dependence are common among people with mental health problems and are a significant factor in admission and prolonged length of hospital stay. In addition, people with co-occurring mental health and alcohol or drug use problems often experience poor health and earlier death. From 2009 to 2019, 47% of people in the UK who died by suicide and were in contact with mental health services, also had issues with alcohol dependency, and 37% with drug addiction. Services should act on the principles of ‘no wrong door’ and ‘everybody’s job’ so that people can access holistic care for both their mental health and alcohol/drug use problems, delivered by staff working in inpatient settings and/or in partnership with specialist addiction services. Here are some suggestions to support this:

- Work in partnership with community alcohol and drug treatment services to provide coordinated care and discharge planning. This may include embedding drug and alcohol workers and peer support workers/lived experience practitioners that have experience of alcohol and drug problems within inpatient teams.

- Screen all people for alcohol and drug use, using a recognised screening tool such as ASSIST-Lite.

- Train all ward staff in how to screen for drug and alcohol use, and to assess and identify alcohol and drug dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and associated acute health needs and risks, including increased risk of suicide.

- Where required, provide medically assisted withdrawal for alcohol or drug dependence and medication to avoid drug withdrawal (eg opioid substitution therapy), delivered promptly by staff with specialist addiction competencies.

- Deliver harm reduction interventions, including take home naloxone to reduce risk of overdose and referral for transient elastography to detect liver disease, to people who need them.

- Safely manage and monitor people who are acutely intoxicated on the ward, being cognisant of the increased risks of intoxication, while at the same time ensuring the person is not excluded.

- Ensure that all people with co-occurring alcohol and drug problems are able to access care in line with relevant clinical guidelines, including those from the NICE and Public Health England.

LGBT+ communities

LGBT+ people are more likely to develop mental health problems than non-LGBT+ people, including being more likely to develop depression and anxiety and being at higher risk of experiencing suicidal thoughts and engaging in suicidal behaviour and self-harm. The reasons why there are higher rates of mental health problems are complex, but one contributory factor is that LGBT+ people often experience prejudice and discrimination, which can also occur when they are in hospital. Some things that can improve the care that LGBT+ people receive in inpatient settings, include:

- Having clear posters and signage within services to show that they are LGBT+ friendly, to help create an open environment.

- Using inclusive language and not making assumptions about people’s relationships and gender (including assuming that the gender recorded in their medical record is correct). At admission, it is good practice to sensitively ask people about their sexual orientation and gender identity, and record their preferences (including what pronouns the person uses, which may vary depending on whether they are with family members, friends, with staff members or other people on the ward). The person’s name and pronouns should be respected, including managing this with other people on the ward.

- Identifying what support the person needs in relation to their sexual orientation and gender identity during their hospital stay. For example, this could include having access to peer support workers/lived experience practitioners that are LGBT+, linking people in to support from VCSE sector organisations, and ensuring continued access to gender affirming care (eg hormone replacement therapy, access to appropriate clothes and prostheses).

- Allocating trans individuals to the appropriate ward, in line with guidance on same-sex accommodation.

- Providing appropriate privacy for personal care and being aware of why this might be specifically important if the person is trans/non-binary/gender fluid.

- Being trauma-informed and aware of how someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity may have impacted on their mental health.

- Having clear procedures for responding appropriately to any reports of homophobic or transphobic abuse or sexual safety incidents.

- Providing training (eg ally training), which helps the inpatient team to understand the challenges that people who are LGBT+ experience within healthcare and society and how to ensure inpatient care is inclusive of LGBT+ people’s needs.

- Further information for healthcare professionals on providing inclusive care for LGBT+ individuals can be found in the ABC of LGBT+ Inclusive Communication.

Older adults and people with dementia

Older adults and people with dementia are particularly vulnerable to delirium, falls, poor nutrition and functional decline while in hospital, all of which can result in increased length of stay. This can be exacerbated by difficulties in identifying the required community-based support to enable timely discharge. For example, in 2021/22, length of hospital stay in older adult acute inpatient mental health services was around 80 days nationally compared to around 40 days in general adult acute services.

To support older adults and people with dementia effectively, ensure that there is:

- Engagement with the person’s chosen carer/s on admission and in all discussions about the person’s care and discharge. Carers can bring helpful insights about the person’s needs, for example, in relation to their daily routine, communication preferences, sensory needs, food preferences, and any activities or objects that will help the person’s wellbeing.

- A process in place to ensure that older adults with dementia arrive and leave hospital with their ‘This is me’ form; and that older adults living in a care home arrive and are discharged with their Red Bag; and that the information contained within these resources is used to tailor the person’s care to their needs.

- Access to all the items the person needs to improve their communication and independence, eg glasses, working hearing aids and walking aids.

- Specific focus placed on strengths, life goals and aspirations (including employment) when planning and delivering care, as these can be overlooked for older adults.

- Regular review of physical health conditions and medications, to ensure that the person’s physical health needs are met and are not impacting negatively on their mental health, and to check that any physical health medications are not interacting with the person’s mental state and with any psychotropic medications that the person is taking.

- Access to interventions and activities that take into account any physical or cognitive needs, including dementia.

- Early discussion about the intended discharge location with the person and their chosen carer/s. Online and printed information should be provided to support decision making if someone requires new accommodation or a placement, and proactive action taken to put this in place. For people with dementia, in particular, it can help if they are able to visit the intended discharge location prior to discharge if it is new to them, and discharges late in the day should be avoided, as this can increase disorientation.

- Access to specialist advice and support, eg geriatricians, palliative care, occupational therapists and physiotherapists (to aid rehabilitation), and social care staff (who can help to facilitate complex discharges).

- Appropriate signage, lighting, soft furnishings and flooring on the ward, to maximise independence for people with dementia. In addition, curtains should be closed in the evening as reflections in windows can be misinterpreted and cause distress.

There may be occasions, based on clinical judgement, when it is appropriate to admit an older adult to a general adult ward (eg because they are well known to staff there) or to admit a younger adult to an older adult ward (eg because of physical health issues such as incontinence issues that would be best managed there). Where an older adult is admitted to a general adult ward, their frailty and acuity should be considered in the risk assessment, and reasonable adjustments made. Adjustments should also be made when a younger adult is admitted to an older adult ward, to ensure the person receives care that is appropriate for their needs.

People who are given a diagnosis of ‘personality disorder’

People who are given a diagnosis of personality disorder have particularly poor experiences of inpatient care, including facing prejudices and assumptions about what is driving their distress, and potentially unsafe exclusionary practices. Some people given this diagnosis think that the personality disorder construct is inappropriately applied and feel that it overshadows and invalidates the real issues leading to distress, self-harm and suicidal ideation, and therefore the construct in itself causes further harm.

Some actions that can be taken to improve the care for people given a diagnosis of personality disorder are:

- Listening to how people describe and understand their distress, mirroring their language and offering care based around their mental health needs rather than diagnostic labels, in recognition that some people who are given a diagnosis of personality disorder do not agree with the construct.

- Recognising the role that trauma may have played in a person’s life and their current mental health needs, and seeking to understand how to support them best while they are in hospital, in a way that minimises triggers and retraumatisation. This will involve building therapeutic relationships, offering validating, compassionate support, and working with the person to understand their triggers and how to increase their sense of safety and control while in hospital. See the trauma-informed care section for further detail.

- Emphasising to people that they have a choice over the treatments and interventions they receive and that they can decline treatments if they do not want them (within the limits set out in the MHA and MCA).

- Ensuring staff working in inpatient settings have received training on personality disorders, co-delivered with people with lived experience of the diagnosis.

- Arranging for a trauma specialist and peer support worker/lived experience practitioner to meet people currently experiencing long hospital stays to identify what additional support the person needs to return home and stay well in the community.

- Ensuring that all care is delivered in line with NICE guidelines and quality standards, and that members of inpatient teams attend and apply Knowledge and Understanding Framework (KUF) training on the ward.

People admitted out of area

People that are placed in an inpatient service outside their local area have longer lengths of stay on average, poorer clinical outcomes (including increased risk of suicide) and poorer experience of care. This is often due to the negative impact of being out of area on the continuity of their care and reduced contact with people in their support network. When someone is placed out of area, the care they receive should be as close as possible to the care they would have received locally. This includes:

- The person’s named key worker staying in contact with the person and visiting the person in hospital as regularly as they would have if the person was in hospital in their local trust.

- The person receiving support to maintain regular contact with their chosen carer/s and support network. This must include funding the costs of transport and accommodation to facilitate visits, as well as supporting the use of technology to aid remote communication.

- Supporting the person, as far as possible, to engage in their usual activities and to maintain their responsibilities (eg the upkeep of their home).

- Peer support workers/lived experience practitioners from the person’s local trust keeping in regular contact (minimum weekly).

- The local hospital team maintaining involvement with the person’s care, with the aim of returning the person to their local hospital as soon as a bed becomes available, unless this would be disruptive and unhelpful to the person’s recovery.

When a person is admitted out of area, data must be flowed about the admission by the sending and receiving provider. Further information about how to do this can be found in this webinar. In addition, the FutureNHS platform (requires login) provides access to webinars held with NHS trusts that have had success in reducing the number of people placed of area, as well as the definition of an out of area placement, and details of continuity of care principles. ICSs are expected to monitor compliance with these principles where there is out of area bed use.

Trauma-informed care

Many adults and older adults accessing mental health services and particularly people requiring an inpatient admission, will have experienced trauma at some point in their lives. Furthermore, when people are admitted to hospital, and particularly when a person is detained under the MHA or is subject to a restrictive intervention, it is often accompanied by feelings of loss of power and control, and can be traumatic. It is therefore important that services work to ensure that the support that is offered in hospital is underpinned by a trauma-informed approach, both in terms of the way that care pathways are organised and how care is delivered.

Trauma-informed care first involves recognising that many people in contact with mental health services will have experienced trauma. Staff should talk to the person and their chosen carer/s to understand the role that trauma has played in a person’s life and how it is currently impacting their life and wellbeing. In discussing people’s life experiences and traumas with them, it is important to remember that for some people, asking them to recount their personal story and traumatic experiences, can in itself be retraumatising. Therefore, it is important to make use of what is already known and recorded about a person (eg in their EPR) and give the person choice about whether they wish to discuss these aspects of their life again.

To help restore feelings of control, active efforts should be made to give the person as much choice as possible while they are in hospital, and to work in close collaboration with the person, so that they are at the centre of their care planning. This should include gaining an understanding of how to support the person in a way that reduces the likelihood that they will be triggered or further traumatised by being in hospital, as well as coming to shared decisions with the person about whether they need specific support to help them process any traumatic experiences that they have had.

The physical and emotional environment on the ward should also promote feelings of safety and recovery and members of the inpatient team should work to build therapeutic relationships with people that are based on trust, respect and compassion. For this to happen, it is essential that there is a positive ward culture, where the use of restrictive interventions, including restraint and seclusion, is not seen as standard practice, and where restrictive interventions are used, it is as a last resort, proportionate to the situation and for the minimum time necessary. Managers should undertake regular reviews of practice, to ensure that where restrictive interventions are used, it is absolutely necessary and is applied proportionately.

Furthermore, in order that members of the inpatient team are able to promote positive ward cultures and build therapeutic relationships that keep individual stories at the heart of care delivery, it is essential that their own wellbeing is supported. Services should have processes in place, including reflective practice and supervision, which help team members to process their own thoughts, feelings and reactions to situations that have occurred on the ward, as well as any traumatic experiences they have had outside work (see the workforce section for further details).

The following links provide information to support services to transform the culture of inpatient wards to make them trauma-informed, both in terms of supporting people in a way that recognises and is responsive to the trauma that they may have previously experienced, and in terms of helping to ensure that inpatient care does not itself unintentionally lead to people experiencing new traumas (for example, as a result of inappropriate and disproportionate use of a restrictive intervention):

- Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust’s webpages on trauma-informed approaches.

- The Power Threat Meaning Framework, developed by a network within the Division of Clinical Psychology at the British Psychological Society, which can be used to support a trauma-informed understanding of human distress.

- The Centre for Mental Health and the Mental Health Foundation’s guide to providing effective trauma-informed care for women.

- Surrey and Borders NHS Foundation Trust’s trauma-informed care toolkit for carers, which has a specific focus on people with a learning disability, as well as these webpages from The Challenging Behaviour Foundation on trauma support for people with a learning disability.

- The Reducing Restrictive Practice Collaborative, Restraint Reduction Network and Safewards project (see also Safewards Victoria) webpages, which provide practical information on interventions that can support reductions in conflict and restrictive practice on wards.

- NHS England’s webpages on reducing long term segregation and restrictive practice for people with a learning disability and autistic people, who disproportionately experience these practices. This details information on a number of initiatives including Independent Care (Education) and Treatment Reviews, the HOPE(S) model and the Senior Intervenors Project.

- The Sexual Safety Collaborative – includes guidance and ideas for changing practice to improve sexual safety in inpatient mental health settings.

- Guidance from the Department of Health and Social Care setting out the measures that NHS hospitals and independent hospital providing NHS-funded care must take as part of the Mental Health (Use of Force) Act (2018) to prevent inappropriate use of force in mental health units, including training requirements for staff.

Joined up partnership working

Inpatient services that work closely with a range of other services (see box below for examples) in a collaborative and coordinated way, are more likely to meet people’s varied needs, contributing to improved experiences and outcomes from care and reducing avoidable time spent in hospital. It is particularly important that where someone is transferred from another service, for example, children and young people’s mental health services, that there is strong coordination of care, so that the transition is as supportive as possible.

As part of the initial assessment and admissions process, it is important to read the person’s EPR to identify who they currently receive support from and which services they are in contact with, and to check this back with the person and their chosen carer/s. Resources such as the Circles of Support can be used to help identify the key individuals, communities and services in a person’s life.

It is also important to find out and record people’s preferences about what types of information is shared with the people and services that support them and how they would like them involved in their inpatient care and discharge. The circumstances in which these preferences may not be followed should be explained (see pages 78-82 of the MHA Code of Practice (which includes information on confidentiality whether people are or are not detained in hospital). Where people require reasonable adjustments or have additional needs that fall outside the remit of inpatient mental health services, expertise may need to be sought from specialist services (eg learning disability, autism, drug and alcohol teams). Commissioning arrangements should enable easy referral and responsive input from such teams.

Many people who are admitted to hospital will already be in contact with a community-based mental health or learning disability team and have a named key worker. On admission, anyone without a named key worker should be assigned one within 72 hours, wherever possible. Key workers should maintain contact with the person while they are in hospital and pass on any information that is useful for the person’s care, to help avoid the person having to undergo repeat assessments and retell their story, which can be frustrating and trigger past traumas. The key worker should also work closely with the inpatient team, CRHTT, and any other key services or parties, to identify and put in place the support that the person will need to be discharged and to maintain their wellbeing in the community (including working with local authorities to plan Section 117 aftercare, where applicable). It is important that this is done early and in partnership with other services so that the person’s discharge from hospital to the community is as smooth as possible.

Here are some actions that can be taken to embed effective partnership working:

- Ensure there are clear pathways between services (eg between physical health and mental health services) and joint working arrangements are agreed with partner organisations, which include information on the management of transitions (eg from children and young people’s inpatient services to adult inpatient services).

- Review the inpatient mental health pathway to understand how partnership working is currently functioning and how to strengthen it. For example, this could involve senior system partners and lived experience practitioners coming together on a quarterly basis to review performance data and local intelligence, assess where there are pressures across the pathway and identify actions to drive improvement.

- Integrate members of key partners organisations, for example, social workers and housing officers, as part of the ward team’s staffing establishment.

- Ensure cross-service attendance at key meetings (eg care planning and discharge meetings, and other reviews). This should include representatives from the local CRHTT, the person’s named key worker from the community-based mental health or learning disability team and any other key partners in the person’s care (see box below for examples), as well as anyone that the person and their chosen carer/s feel it would be helpful to have in these meetings.

- Hold joint training between services that work with one another, where relevant, to understand the types of expertise that different services and professionals offer, as well as to reflect on and improve joint working processes. As an example, this could be used to share reflections about what more could be done to avoid escalation to admission, or to identify situations in which people are better cared for in the community.

- Develop clear escalation protocols with cross-agency partners, which set out when and how to raise issues to senior managers – the protocols should clearly identify where senior responsibility sits along with contact details to enable timely escalation to occur. Escalation protocols should exist for occasions when there are long waits in A&E, challenges in locating inpatient provision for urgent admissions, and delayed discharges from hospital. These protocols should be developed and maintained by the ICS, with input and agreement from NHS mental health providers and relevant partners included in the box below, who are key to the operation of the local pathway. More information about Section 140 compliant escalation protocols is set out in this section of the guidance.

Key services for effective partnership working in inpatient mental health care

Please note, this is not intended to be exhaustive.

- CRHTTs

- Community-based mental health teams

- A&E, psychiatric liaison and diversion services

- Primary care

- Pharmacy services

- Services addressing sexual health and physical health needs (including community health, intermediate care and frailty services for older adults)

- Children and young people’s mental health services

- Community learning disability services and specialist autism services

- Gender identity services

- Drug and alcohol services

- Specialist trauma services

- Local authorities, in particular, Approved Mental Health Professional (AMHP) services, expert housing teams, and children and adult social care teams, including safeguarding specialists and those responsible for conducting needs assessments and arranging Section 117 aftercare (in partnership with integrated care boards (ICBs)

- Housing services (offering home adaptations and short- and long-term housing options)

- Rehabilitation services providing advice and specialist intervention

- Carers support services

- Financial support services providing advice on benefits and funding of ongoing care

- Employment support services

- Education services – including schools and further and higher education providers

- Criminal justice agencies, including probation and the police

- Independent sector providers (especially where people are placed in a non-NHS inpatient service)

- VCSE sector organisations providing advocacy services, peer support, community crisis alternatives, and in-reach services for specific groups, including people from racialised and ethnic minority communities.

Effective care across the inpatient pathway

For people to have the best recovery possible, they need to receive effective care from pre-admission, during their hospital stay and after discharge. This includes ensuring:

- Admissions are purposeful – people are only admitted to inpatient care when they require assessments, interventions or treatment that can only be provided in hospital, and if admitted, it is to the most suitable inpatient service provision available for the person’s needs and there is a clearly stated purpose for the admission.

- Their inpatient care delivers therapeutic benefit – care is planned and regularly reviewed with the person and their chosen carer/s, so that they receive the therapeutic activities, interventions and treatments they need each day to support their recovery and meet their purpose of admission.

- Their discharge is proactively planned and effective – the person’s discharge is planned with them and their chosen carer/s from the start of their inpatient stay, so that they can leave hospital as soon as they no longer require assessments, interventions or treatments that can only be provided in an inpatient setting, with all planned post-discharge support provided promptly on leaving hospital.

The sub-sections that follow explain each of these stages of the inpatient journey in more detail.

Purposeful admissions

Ensuring that people are only admitted to inpatient care when they require assessments, interventions or treatment that can only be provided in hospital, and if admitted, it is to the most suitable available inpatient service provision for the person’s needs, and there is a clearly stated purpose for the admission.

Deciding whether an inpatient admission is required, or the person could be supported through a less restrictive community-based acute care model

When people are in crisis, they require prompt access to the right support, in the best setting for their needs. For people with a learning disability and autistic people, a C(E)TR should normally take place pre-admission, in line with current policy, to understand the person’s needs and determine if they could be met in the community or whether they require an inpatient admission. For people who do not have a learning disability or autism, a holistic face-to-face assessment (see Appendix 3) should be conducted to understand the person’s care needs and preferences in relation to treatment.

This assessment should include identifying who the person’s chosen carer/s are and what their views are about the person’s care. To avoid the person needing to retell their story, the person’s EPR should be reviewed at the earliest opportunity, ideally prior to their initial assessment, to gather information from any prior assessments and care plans and to identify any advance choices. This information should be checked back with the person and their chosen carer/s in case there have been changes.

Based on the assessment and taking the person’s wishes into consideration as far as possible, a decision should be made about whether it would be better for the person to be admitted to hospital (including admission under the MHA) or whether it would be better for the person to be supported in the community. This may through support from a community-based acute mental health service, such as a CRHTT, acute day service or crisis house, or an intensive support team, for people with a learning disability (examples of community-based alternatives to inpatient care can be found in the case studies section on the FutureNHS platform (requires login). Given that long lengths of stay in hospital can in themselves be harmful, decision-making needs to explicitly consider whether a hospital admission is essential because the person requires assessments, interventions and/or treatment that can only be provided in hospital and could not be delivered through community-based acute services.

Though it will not always be the case, often receiving care and treatment at home or in a less restrictive community setting can lead to a better experience of care because it means that the person can more easily maintain existing routines, access to their usual support network and can stay in a more familiar location. This is illustrated in the extract below from someone who experienced a mental health crisis:

“Fortunately, one nurse who was caring for me went above and beyond to see that I was not admitted. He talked to my wife, who deemed it would be better for me to be cared for at home. No one else did this or took it upon themselves to find out my background and what happened that brought me to this point. The nurse was persistent with their encouragement and support and fought long and hard to ensure the wrong decisions were not made. I even remember him challenging the doctor who wanted to admit me… All these things had a huge impact on my recovery and eventually helped me to start caring for myself again.”

There are two main models used by providers to assess whether an inpatient admission is required, or the person could be supported through a community-based acute model:

- CRHTTs conducting all assessments for acute care, because of their expertise in knowing the care and treatment options available locally, including community-based acute care and inpatient care.

- A trusted assessor model in which CRHTTs are responsible for conducting most acute care assessments (eg those that come in via referrals to the CRHTT or the single point of access), but other teams, eg psychiatric liaison and community-based mental health teams, may complete assessments and CRHTTs then base decision-making about the most appropriate care option on this assessment and do not have to see the person face-to-face.

Regardless of which model is used, it is important that:

- Repeat assessments by different services are reduced wherever possible, as well as the need for people to wait for teams to arrive to conduct assessments.

- CRHTT clinicians are empowered to lead decision-making, working in close partnership with the person and their chosen carer/s and partner services, whose expertise may be useful to reach decisions about the most appropriate care setting. For example, involving AMHPs early on in the assessment process can support consideration of less restrictive alternatives to detaining people under the MHA. To help partnership working in relation to deciding the most appropriate care setting:

- There should be a policy setting out roles and responsibilities in relation to crisis and acute assessments, which provides details of inpatient and community-based acute services available locally, together with key referral information.

- There should be regular reviews of need versus capacity across the different inpatient and community-based acute services available locally, to ensure the system is set up to meet the current population need.

- CRHTTs, psychiatric liaison teams, inpatient teams and AMHP services should aim to operate as part of one wider team, communicating regularly in relation to team capacity and presentations in the community and A&E. This helps to build relationships and trust and enables more informed decision-making around the most appropriate care setting.

- Where someone needs to be assessed under the MHA, there should be clear protocols in place locally for securing the necessary input from Section 12 approved doctors and an AMHP in a timely way, and ensuring all key information is communicated to support the assessment.

- All services involved in conducting assessments (including CRHTTs, psychiatric liaison services and AMHPs) that feed into decisions around admission, meet regularly to share feedback and to address issues, so that all parties have confidence that admission decisions are being made appropriately, consistently and in people’s best interests.

- There is senior clinical oversight to check that there is clarity and consistency around decision-making in relation to whether people receive community-based acute care or are admitted to hospital.

Agreeing a purpose of admission

When it is judged that an inpatient admission is required, the reasons identified for this should be formalised in a purpose of admission statement, which clearly articulates why an inpatient stay is needed and the aims of the admission (see box below for example statements). Evidence from local quality improvement initiatives has shown that when a purpose of admission is recorded, it reduces the risk of people staying in hospital longer than needed. Furthermore, the intended reforms to the MHA, outlined in the draft Mental Health Bill, include new detention criteria requiring admissions to provide therapeutic benefit. By recording a purpose of admission, it helps to ensure that the inpatient team is clear on the therapeutic benefit that an admission should achieve and can work with the person, their chosen carer/s and any relevant partner services to achieve it.

Formalising a purpose of admission should be done for each person admitted to hospital, regardless of the time of day or who is doing the assessment, and should follow a consistent process that is established by the provider (eg incorporating it into initial assessment forms). It should be uploaded to the person’s EPR, together with an EDD. The purpose of admission and the EDD should also be shared with the person, and where appropriate, with their chosen carer/s and relevant partner services.

| Examples of good (*) and poor quality (×) purpose of admission statements |

| * Ayele, who is being supported by the Early Intervention in Psychosis service, is having a relapse in the community following a breakup with her partner, and has stopped taking her clozapine medication. It is known that re-starting Ayele on medication at home will not be successful and therefore hospital admission will be used to identify why she stopped taking the clozapine medication, including whether any aspects of her care plan need changing to address the reasons identified. One thing that Ayele mentioned at admission was feeling lonely so her ongoing care plan will need to include support in helping her to address this. EDD: 14 days. * Krish has been receiving treatment for a diagnosis of bipolar disorder from a community mental health team, alongside support from his local drug treatment service. He was doing well with managing his bipolar and drug use, until the death of his uncle. On Friday, he attended the local A&E, having made a serious attempt to take his own life. He had not taken his daily medication for more than four days. An admission is required to re-establish his medication and to understand what would help him to manage his bereavement. This support will then be put in place as part of his ongoing care plan. EDD: 21 days. * Reggie has recently become homeless and has been brought to a health-based place of safety by the police, because he was displaying a high level of mental distress in public. He is not known to mental health services. Reggie has been assessed as requiring admission under Section 2 of the MHA. Admission will be used to assess his mental state and identify his strengths, needs and aspirations, including how he usually manages in his day to day life, why he became homeless and what factors contributed to his mental health crisis. This will inform his ongoing care plan, including setting out which pharmacological, psychological, social and practical interventions are required to support Reggie’s recovery in the community. EDD: 21 days. × Mike required admission under Section 3 of the MHA. EDD: unknown. × Aarvi has been admitted to maintain their safety. EDD: Will be discharged once risk assessment shows it is safe to discharge Aarvi. |

Arranging prompt access to the most suitable hospital provision for the person’s needs

It is expected that when someone requires an admission, they will receive prompt access to the most suitable inpatient service that is available for their needs and begin receiving inpatient support as swiftly as possible. If someone is experiencing an unacceptably long wait for an inpatient bed and this has not been resolved through routine processes such as bed management meetings, then system-wide escalation protocols should be followed. These escalation protocols should be developed and shared with multi-agency partners (eg local authority, police and A&E departments) and must be compliant with Section 140 of the MHA, which is a duty on local NHS commissioning bodies to provide every local social service authority with a list of hospitals that can receive urgent mental health admissions, and enable applications under the MHA, if necessary. On a regular basis, including after an escalation protocol has been activated, multi-agency reviews should take place to help identify what more can be done to unlock capacity across the system and help ensure that people can access inpatient mental health services in a timely way when they need them.

Other than in exceptional circumstances, it is usually best for people to be admitted to their local acute inpatient mental health service, so that they can more easily maintain contact with friends, family and local community care teams. There are a small number of circumstances in which it is appropriate to admit someone out of area who requires a non-specialist acute mental health admission. These are:

- personal choice

- an emergency admission (eg where someone is visiting or on holiday in another area of the country)

- safeguarding concerns if the person was to be placed in their local hospital

- the person being a member of staff at the local trust.

Where one of these reasons applies, admission to a non-local hospital should be facilitated.

Where someone is admitted out of area and none of these reasons apply (ie it is an inappropriate out of area admission), this should be communicated to the senior responsible clinicians within the local provided, and the good practice suggestions provided earlier in this document should be followed. Furthermore, as soon as clinically appropriate, the person should be transferred back to their local hospital, unless there is a good reason not to (eg it will disrupt the person’s continuity of care, or the person wants to remain in the current hospital setting).

Therapeutic inpatient care

Care is planned and regularly reviewed with the person and their chosen carer/s so that they receive the therapeutic activities, interventions and treatments they need each day to support their recovery and meet their purpose of admission. Purposeful care in a therapeutic environment supports people to get better more quickly and reduces avoidable time spent in hospital.

Once a person has been admitted to hospital, they should receive care that delivers therapeutic benefit throughout their inpatient stay. This section of the guidance covers some of the key areas that acute mental health services should focus on to deliver high quality, therapeutic inpatient care.

Care formulation and planning

To understand and plan the support and interventions that an individual needs to meet their purpose of admission and to receive therapeutic inpatient care, a formulation review should take place within 72 hours of admission. The purpose of this formulation review is to build on information from the person’s EPR, including any prior assessments, existing care plans and recorded advance choices, to develop a holistic and compassionate understanding of the individual. This includes their current experiences and difficulties, what led to their admission and the reasons behind why they are showing signs of mental distress (including any current or past trauma). The formulation review should also look at the person’s treatment and support preferences, what they want their recovery to look like, their strengths, and any protective factors (eg supportive relationships, activities, and routines) that will help them to get better.

Building on the formulation process, a care plan should be co-produced with the person and their chosen carer/s (please note, it will be a statutory requirement for people detained under the MHA to have a Care and Treatment Plan, if and when the draft Mental Health Bill is passed into law). The care plan should include information on the assessments, interventions and activities that will be delivered while the person is in hospital and any considerations in terms of the way that the support is delivered. As part of early discharge planning, the care plan should also include information on what support will be needed after discharge (including housing and social care) to support the person’s recovery and maintain and improve their longer-term wellbeing. See the Discharge section for further details.

To ensure that everyone is clear on the actions that will support the person’s recovery and their role in delivering this, the written care plan should be uploaded to the person’s EPR and shared with the person, and where appropriate, their chosen carer/s and any other relevant parties. The copy that is shared should be in a format that is accessible (eg free of acronyms and jargon), and where required, provided in alternative formats, such as in translation.

Both formulation and care planning work best when it is a collaborative process between the person, their chosen carer/s, the inpatient multi-disciplinary team (MDT) and representatives from partner services who know the person well and are involved in supporting the person (eg the person’s named key worker, housing officer or advocate). An atmosphere of shared learning should be created, with equal value placed on the perspectives of each person involved. For some services, co-producing care plans will involve a shift in the way that teams usually work, to one in which the power to make decisions is shared with the person and their chosen carer/s.

In some cases, the person may not be ready or able to be fully involved in co-producing their formulation review or care plan, particularly at the start of their admission. In these instances, it is still important that the inpatient team listens to the person, offers the person choices and seeks to find out their needs and preferences, drawing on information including from their chosen carer/s, named key worker and EPR. As soon as it is possible, it is vital that the inpatient team engages the person fully in co-producing and refining their care plan. Where there are reasons that care cannot be delivered in line with the person or their chosen carer/s preferences, this should be clearly explained to them, recorded in the person’s EPR and revisited at a later stage, wherever possible.

Delivering therapeutic activities and interventions

In line with their purpose of admission and care plan, each person should receive access to the assessments, activities, interventions and treatment that they need, which aid their recovery and improve their ability to respond to future crises. The additional funding allocated to therapeutic inpatient care through the NHS Long Term Plan is intended to support providers to achieve this, particularly through increasing the number of therapeutic staff in inpatient settings, including occupational therapists, peer support workers and psychologists, who can support the delivery of a range of activities and interventions.

Interventions

As part of person-centred care planning, the evidence-based interventions that the person will receive in hospital should be agreed with the person and their chosen carer/s. These interventions should meet the person’s holistic needs (pharmacological, psychological, social and practical), and be delivered in a way that is culturally appropriate and adjusted to meet individual needs. For example, for people with a learning disability and autistic people, this could include providing one-to-one support to enable participation.

The range of interventions that should be offered on wards, and delivered to people based on their individual needs and care plans, includes:

- Physical health support

- On admission, any known physical health conditions should be identified, and any existing treatment/management plan should be continued in hospital (appropriate advice should be sought if any changes are needed).

- A physical health check should be completed within 72 hours of admission. This should consider height and weight, heart rate and blood pressure, blood glucose and lipid profile, the physical effects of medication, sexual health, use of cigarettes, alcohol and drugs, and any other areas depending on clinical need (without rescreening for conditions that are already known and which the person is receiving treatment for). Assessments should be optional (except where clinically necessary), the reasons for doing them clearly explained, and they should be conducted sensitively to avoid discomfort and distress.

- A physical health plan should be developed with the person and their chosen carer/s based on the physical health check. This may cover diet and exercise, treatment to manage long-term conditions (eg diabetes, cardiovascular disease), sexual health, smoking cessation, and alcohol and drug use (including detox and managing withdrawal).

- Psychotherapy – people’s need for psychology input, including ongoing therapy when the person leaves hospital, should be assessed as part of care and discharge planning. This guide from the Association of Clinical Psychologists and the British Psychological Society provides useful information on psychology input across the acute mental health pathway, while this quality statement from NICE provides specific information in relation to psychological interventions for people with a learning disability.

- Relapse prevention – individual or group support, particularly for people who are approaching discharge, to help establish strategies for managing their physical and mental health after leaving hospital (including identifying individual triggers and early warning signs of worsening mental health, and how to manage these) as well as to plan their daily routine and identify personal goals for after discharge.

- Medication – regular medication reviews (every 2-3 days) should take place throughout a person’s admission, which involve working collaboratively with the person to consider medication type, dosage, interactions and side effects. These resources from NHS England on STOMP (Stopping over medication of people with psychotropic medications) can help services to reduce the overuse of psychotropic medication for people with a learning disability and autistic people.

- Peer/lived experience support – group or individual support, provided by peer support workers/lived experience practitioners, with a diverse range of experiences (eg in terms of cultural background, age, diagnosis).

- Education and employment support – considering support to access training, higher and further education, apprenticeships and paid and voluntary work.

- Financial support – including use of the Breathing Space debt relief scheme and guidance on benefits and funding of ongoing care.

- Housing support – for example, this could involve meeting with an in-reach housing officer to discuss accommodation options post-discharge, if the person is not able to return to where they were living pre-admission.

- Specialist support and interventions to meet individual needs, particularly for groups that experience inequalities within the local acute pathway. These may be delivered through VCSE sector services.

Activities

To supplement these interventions, there should be a programme of activities and groups that help to improve people’s physical and mental wellbeing. These activities and groups should run daily on each ward, including at weekends and in the evenings.

The types of activities and groups available should be co-produced with people who are currently on the ward and people who have used inpatient services, to suit a variety of interests and needs. There should be age-appropriate and single sex activities offered, and a focus on ensuring that activities are culturally appropriate and appropriately adapted to meet the needs of groups that are identified as experiencing health inequalities. Providers may wish to commission VCSE sector services to support these aims.

It is important that while encouraging participation in activities and interventions, individuals are both given the choice to decline taking part, based on their interests and what they think will be of therapeutic benefit to them. Equally, people should not be denied access to therapeutic activities and interventions based on a disability, diagnostic label or another protected characteristic, including inappropriate judgements about the likely effectiveness of an intervention based on any characteristic.