The saving babies’ lives care bundle v3.2 – summary of changes

- updated implementation guidance to reflect the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts (CNST) Maternity Incentive Scheme Safety Action 6 (Implementing version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle)

- revised sections on equity and midwifery continuity of carer (Principles to be considered alongside implementing version 3)

- changed wording of interventions 2.4, 2.10 and 2.12; removed outcome measure 2e (Element 2)

- clarified which blood pressure monitors meet NHS standards (Element 2)

- updated intervention 3.3 and outcome measures 3a and 3c (Element 3)

- revised interventions 4.3, 4.4 and 4.5 (Element 4)

- updated interventions 5.9 and 5.11; removed intervention 5.14 and measures 5d and 5h (Element 5)

- renumbered and revised interventions 5.18 to 5.26 and measures 5b and 5h (Element 5)

- added note on fetal fibronectin test supply issues (Element 5 – Implementation)

- updated interventions 6.2, 6.3 6.5 and 6.12 to align with Hybrid Closed Loop strategy (Element 6)

- revised measures 6b, 6d and 6f; added explanatory sections on Hybrid Closed Loop (Element 6)

- removed original Appendix B and replaced with signposting to public health guidance (Principles to be considered alongside implementing version 3)

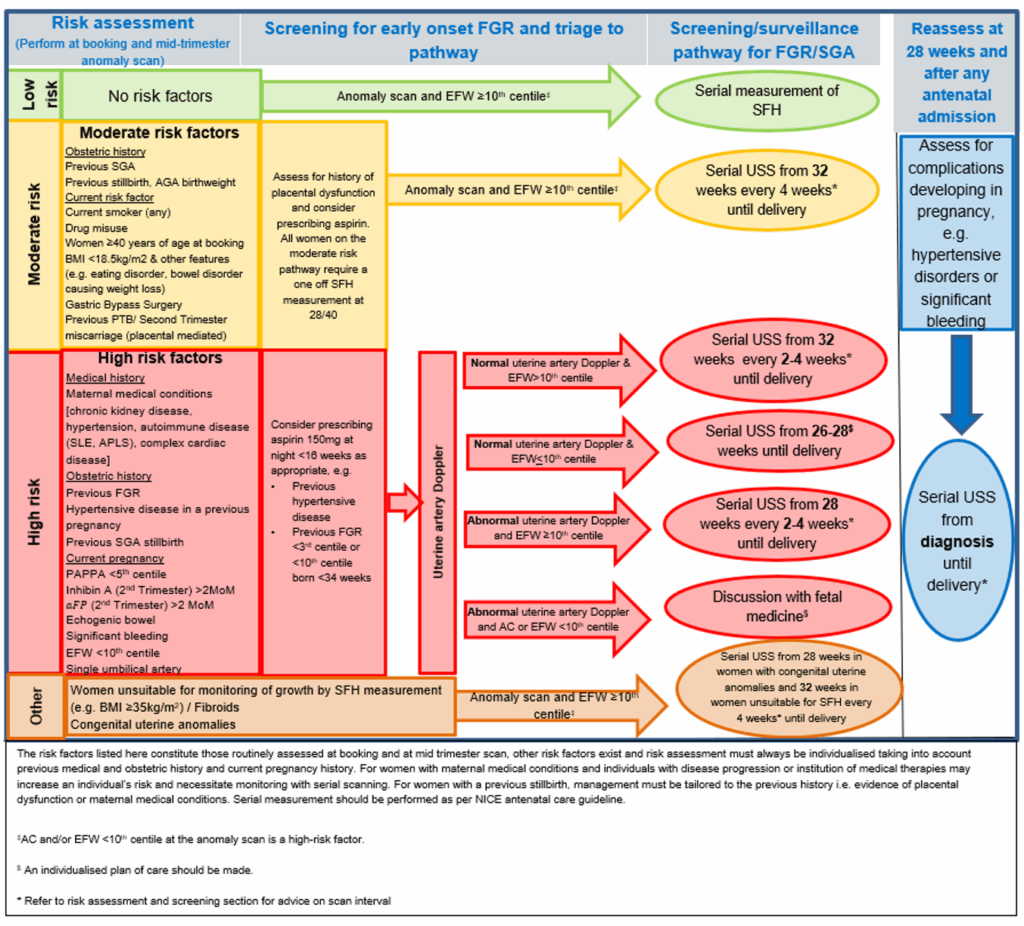

- updated Appendix C Figure 1: Algorithm for using uterine artery Doppler as a screening tool for risk of early onset FGR (Appendix C)

- updated Appendix B Table 1: Clinical risk assessment for pre-eclampsia as indications for aspirin in pregnancy (Appendix B)

Summary

The Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle (SBLCB) provides evidence-based best practice for providers and commissioners of maternity care across England, to reduce perinatal mortality.

The NHS has worked hard towards meeting the national maternity safety ambition, to halve rates of perinatal mortality from 2010 to 2025 and achieve a 20% reduction by 2020. Office for National Statistics (ONS) data showed a 25% reduction in stillbirths in 2020, but against the same baseline only 20% in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Much has been achieved in the past few years, but more recent data shows there is more to do to achieve the ambition in 2025.

Version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle (SBLCBv3) has been co-developed with clinical experts including frontline clinicians, Royal Colleges and professional societies; service users and maternity voices partnerships; and national organisations including charities, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and a number of arm’s length bodies (see Appendix A: Acknowledgements).

Building on the achievements of previous iterations, version 3 refreshes all existing elements, drawing on national guidance, such as that from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Green Top guidelines, and frontline learning to reduce unwarranted variation where the evidence is insufficient for NICE and RCOG to provide guidance. It adds a new element on the management of pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy, based on data from the National Pregnancy in Diabetes (NPID) Audit.

This means there are now 6 elements of care:

Element 1 focuses on reducing smoking in pregnancy by implementing NHS-funded tobacco dependence treatment services within maternity settings, in line with the NHS Long Term Plan and NICE guidance. This includes carbon monoxide testing and asking women about their smoking status at the antenatal booking appointment and, as appropriate, throughout pregnancy. Women who smoke should receive an opt-out referral for in-house support from a trained tobacco dependence adviser who will offer a personalised care plan and support throughout pregnancy.

Element 2 covers fetal growth: risk assessment, surveillance and management. It builds on the widespread adoption of mid-trimester uterine artery Doppler screening for early-onset fetal growth restriction (FGR) and placental dysfunction. Element 2 seeks to further improve FGR risk assessment by mandating the use of digital blood pressure measurement. It recommends a more nuanced approach to late FGR management to improve the assessment and care of mothers at risk of FGR and lower rates of iatrogenic late preterm birth.

Element 3 is focused on raising awareness of reduced fetal movement (RFM). It encourages increasing awareness among pregnant women of the importance of reporting RFM and seeks to ensure providers have protocols based on best available evidence in place to manage care for women who report RFM. Induction of labour before 39 weeks’ gestation is only recommended where there is evidence of fetal compromise or other concerns in addition to a history of RFM.

Element 4 promotes effective fetal monitoring during labour through ensuring all staff responsible for monitoring the fetus are competent in using the techniques of intermittent auscultation and/or CTG in relation to the clinical situation, use the buddy system and escalate accordingly when concerns arise or risks develop. This includes staff who are brought in from other clinical areas to support a busy service, as well as locum, agency and bank staff.

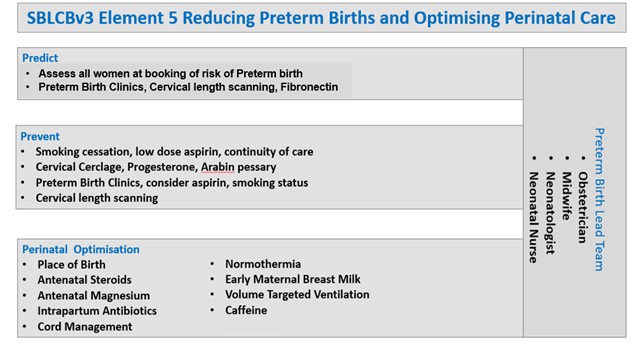

Element 5 on reducing preterm birth recommends 3 intervention areas to reduce adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes: improving the prediction and prevention of preterm birth and optimising perinatal care when preterm birth cannot be prevented. All providers are encouraged to draw on the learning from the British Association of Perinatal Medicine toolkits and the wide range of resources from other successful regional programmes (for example, PERIPrem resources, MCQIC).

Element 6 covers the management of pre-existing diabetes for women with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, as the most significant modifiable risk factor for poor pregnancy outcomes. This element recommends multidisciplinary team pathways and an intensified focus on glucose management within maternity settings, in line with the NHS Long Term Plan and NICE guidance. It includes clear documentation of assessing glucose control digitally, using HbA1c to risk stratify and provide additional support / surveillance (National Diabetes Audit data), and consistently offering access to evidence-based continuous glucose monitoring and pregnancy-specific hybrid closed loop technology to improve glucose control.

In addition to the provision of safe and personalised care, achieving equity and reducing health inequalities is a key aim for all maternity and neonatal services and is essential to achieving the national maternity safety ambition. In developing each element in SBLCBv3, actions to improve equity have been considered, including for babies from Black, Asian and mixed ethnic groups and for those born to mothers living in the most deprived areas, in accordance with the NHS equity and equality guidance.

As part of the Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services, NHS trusts have been responsible for implementing SBLCBv3 by March 2024 and integrated care boards for agreeing a local improvement trajectory with providers, along with overseeing, supporting and challenging local delivery.

SBLCBv3 also sets out the important wider principles to consider during implementation. These reflect best practice care and following them in conjunction with the 6 elements is recommended, but are not mandated by the SBLCB.

Forewords

ONS data suggests that because of the improvement in the perinatal mortality rate since 2010, at least 900 more families will return home with a healthy baby. That is a great achievement, and all those who work in maternity and neonatal services should be incredibly proud of our progress towards the national maternity safety ambition.

The recent rise in the perinatal mortality rate is likely to relate to the direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and is a stark reminder that there will always be challenges to reducing stillbirths and neonatal deaths. The trajectory to meet the national maternity safety ambition was unlikely to be a simple linear progression, particularly as the factors that lead to avoidable perinatal mortality are many and varied. We should all acknowledge that while we have reduced avoidable deaths, there is more to be done.

If we are to meet the national ambition for a 50% reduction in the stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates by 2025, we need to address longstanding inequitable outcomes associated with ethnicity and levels of deprivation. While it is clear that some solutions lie beyond the control of the health sector, our services must do everything possible to mitigate against the wider social determinants of health to continue to drive down the perinatal mortality rate.

The need to continuously iterate and improve care is why we have developed version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle at pace. Clinical experts, professional bodies, charities, service users and national regulators have collaborated to develop national best practice. However, it is important to remember that the care bundle is just one of a series of interventions to help reduce perinatal mortality and preterm birth and shouldn’t be implemented in isolation. The Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services describes more broadly how providers should continue to implement best practice care wherever possible and a set of wider principles are included in the care bundle.

Despite the recent set back in perinatal mortality rates the stillbirth rate was still 19% lower in 2021 than in 2010 and the neonatal mortality rate 30% lower. Thank you to all those who work tirelessly to drive improvement in our maternity services, whether they be NHS employees, parents or charities. I am confident that the collaborative approach modelled by the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle will continue to deliver improvements in outcomes and reduce the number of parents who have to face the tragedy of perinatal bereavement.

Donald Peebles, National Clinical Director for Maternity, NHS England

On behalf of the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), I welcome the publication of version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle. We continue to support the ambition to achieve a 50% reduction in stillbirths and maternal and neonatal deaths by 2025. The care bundle to date has made a vital contribution to achieving this.

The RCM knows that the relationships that professionals form in the workplace, in their teams and with women, are key to safety and preventing the avoidable tragedies of stillbirth and the death of babies. We are therefore pleased to see continued emphasis on professionals working together and with women to help them make choices about their care and reduce the risks to their baby.

Gill Walton, Chief Executive, Royal College of Midwives

As Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle (SBLCBv3) enters its 3rd edition and its 7th year, it continues to innovate and drive forward quality improvement in key areas of maternity care. We welcome the addition of an element covering diabetes in pregnancy and the continued development of the other successful 5 elements. This version builds on versions 1 and 2, to focus on supporting those caring for pregnant women and to help support women to make choices about their care and reduce unnecessary intervention.

Whenever a new guideline is introduced, it will always have limitations and there will be compromises to be made, influenced by lack of current evidence and resource requirements to support successful implementation. However, the premise of the bundle is to reduce variation and provide a framework for continuous improvement. This will be supported by ongoing learning from evaluation of the bundle and is key to its success and value.

The Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle is part of a number of initiatives to improve maternity care and safety. However, there are areas that we urgently need to address if we are to ensure a continued reduction in perinatal mortality for all women and babies. We must, therefore, harness the expertise and experience of obstetricians and specialists in fetal and maternal medicine, frontline maternity teams, academics and policy-makers to tackle inequality and the social determinants of health in the pregnant population.

The British Maternal and Fetal Medicine Society is honoured to have worked closely on all 3 versions of SBLCB and fully supports the initiatives within this new version and the opportunity to work to deliver improvements in maternity care.

Kate Morris, President, British Maternal and Fetal Medicine Society

Every day, maternity services support thousands of women and their families through pregnancy and childbirth. The majority of those using maternity services have good outcomes and report a positive experience of care but maternity care is complex and, unfortunately, adverse events occur.

Recent independent inquiries into maternity care have emphasised the importance of continued learning and action on improving safety. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists warmly welcomes the publication of version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle, which will support further progress towards a 50% reduction in the rate of stillbirths, neonatal mortality and serious brain injury and a reduction of preterm births from 8% to 6% in the UK by 2025, as set in the NHS Long Term Plan.

Maternity care is delivered through multiprofessional teams working together to support all women, requiring a wide range of skills, knowledge and expertise, and a supportive context in which these can be applied. By implementing the evidence-based, best practice elements of the care bundle, local maternity teams can ensure women receive personalised care that will continue to reduce perinatal mortality.

Importantly, each element of the care bundle includes action to improve equity, including for babies from Black, Asian and mixed ethnic groups and for those born to mothers living in the most deprived areas. Maternity systems must continue work to embed these into their local action plans.

The care bundle aligns with and complements a range of other important maternity safety initiatives and tools, including wider work being taken forward through the Maternity Transformation Programme as well as initiatives such as the Avoiding Brain Injury in Childbirth (ABC) programme.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists will continue to work with partners, including other Royal Colleges, national policy-makers and safety leaders, to support the NHS to implement these together, to improve the quality and safety of care that women and babies receive in the UK.

Dr Ranee Thaker, President, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Having achieved the first national maternity safety ambition milestone of reducing by 20% the perinatal mortality rate by 2020 the focus is now on achieving the further 30% reduction by 2025. This will require accelerated progress in the face of having probably dealt with the ‘easier’ problems to prevent and manage.

Activities on multiple fronts are going to be required, which is why, among other actions, the full implementation in all trusts of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle is needed. This, the 3rd version of the care bundle, is a welcome reminder of the 5 elements from version 2 and the introduction of a 6th new element to improve diabetic management in pregnancy for women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

As demonstrated in the National Diabetes in Pregnancy Audit, monitoring and managing tight glycaemic control from pre-pregnancy and throughout pregnancy is key to reducing the risks of adverse outcomes including congenital anomalies and perinatal death. The 2022 MBRRACE-UK Maternal Confidential Enquiry illustrated the risks to both diabetic pregnant women and their babies of poorly managed diabetic ketoacidosis.

The steps outlined in Element 6 of the new version of the care bundle provide practical advice for service delivery to support improved management for this high-risk group of mothers and babies. Achieving the improvements that could be realised from the full implementation of all 6 elements of the new version will provide some of the essential pieces of the jigsaw of activities still needed to further reduce the national rate of perinatal deaths.

Professor Jenny Kurinczuk, Professor of Perinatal Epidemiology, Director, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, National Programme Lead MBRRACE-UK/PMRT, University of Oxford

Despite falls in perinatal mortality in recent years, too many parents and families are still devastated by the death of their baby. The exact impact of COVID-19 is as yet unclear but it’s very possible that the pandemic has had a significant negative impact not just on women and pregnant people’s experiences of maternity, but crucially on outcomes for both them and their babies. Importantly, the government is unlikely to meet the national maternity safety ambition to halve stillbirths and neonatal baby deaths by 2025.

Coming in the wake of further investigations into poor care such as the Ockenden and East Kent reports, this 3rd version of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle has urgency towards ensuring better, safer care. This new version maintains the focus of version 2 but adds another crucially important element around caring for women with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes who we know to be at 4–5 times increased risk of losing their baby. This version also encourages awareness among those who are pregnant of the importance of early warning signals that something may be wrong, such as noticing and reporting reduced fetal movement.

An innovation in this version is an assurance tool to help trusts track their progress in implementation, thereby removing the need to have regular implementation surveys.

Listening to bereaved parents’ experiences is vital in understanding why babies die, and learning from every baby’s death is an essential part of the continual improvement that underpins this care bundle. Parents tell us that if lessons can be learned from the death of their baby it can help them live with their grief, providing an important and lasting legacy.

This updated, 3rd version of the care bundle carries essential knowledge for every healthcare professional who supports and works with those who are pregnant. It helps address inequalities with the same emphasis of continuity of carer, especially for those from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds and those living in areas of social deprivation. When the worst happens, it ensures standards in bereavement care, in line with the National Bereavement Care Pathway.

We welcome its implementation and believe that it provides an opportunity to protect babies’ lives in the future.

Clea Harmer, Chief Executive, Sands

Tommy’s work is dedicated to reducing rates of pregnancy complications and baby loss as we know the heartbreak and devastation this causes far too many parents and families. Despite ambitious targets, the rates of stillbirth and preterm birth are not falling as quickly as we would have hoped, and indeed the stillbirth rates sadly rose in 2021. It is also clear that variation in care continues, and not all women and birthing people have the same chance of taking home a healthy baby – the outcome every family deserves.

So, we warmly welcome version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle as a vital resource for all professionals involved in supporting people to have a safe and healthy pregnancy and birth.

Research is continually advancing understanding and growing evidence and it is vital this is translated into improvements in care. While this guidance has been produced before the evaluation of version 2, we support the fast tracking of new evidence so that everyone can benefit as quickly as possible, and potentially more babies’ lives can be saved.

We know from the MBRRACE data that some communities continue to experience much poorer outcomes than others. This is unacceptable and we’re therefore particularly pleased that version 3 has been reviewed from an inequity standpoint and highlights the promotion of equity and equality as an important principle to apply when implementing the care bundle. It is also positive to see that continuity of carer is explicitly noted as a key intervention to improve equitable outcomes.

A key addition to version 3 is the management of diabetes in pregnancy. The number of women and birthing people with diabetes is on the rise and perinatal mortality rates for pregnant people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes have remained very high for the last 5 years. This practical guidance should standardise pathways and join these up with other aspects of maternity care to reduce risk.

The care bundle also contains a renewed focus on reduced fetal movement (RFM). This is such an important message given the relationship between episodes of RFM and stillbirth, and the vital role of timely hospital attendance and fetal monitoring. Everyone must feel they can and should contact their hospital if they are worried that their baby’s movements have changed.

This version of the bundle is another important step on the journey to safer pregnancy and birth. We know that when all maternity units follow these actions, fewer families will face the heartbreak and devastation of pregnancy complications and loss.

Kath Abrahams, Chief Executive, Tommy’s

Preterm birth causes 78% of deaths in the neonatal period (first 28 days of life; National Child Mortality Database Thematic Report: The contribution of Newborn Health to Child Mortality across England, July 2022) and is also a major contributor to childhood disability and poorer neurodevelopmental outcome. Interventions to reduce the impact of prematurity on morbidity and mortality must therefore be a major focus to move towards the national maternity safety ambition to halve the rate of stillbirth, neonatal death, maternal death and serious intrapartum brain injury by 2025.

BAPM therefore welcomes expansion of Element 5 in version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle, which aims to reduce preterm birth where possible and optimise perinatal care where preterm birth cannot be prevented. Given the importance of the interventions in improving outcomes, BAPM strongly encourages trusts to ensure that appropriate time is allocated to the neonatal medical and nursing leads of the preterm birth team, in addition to the maternity and obstetric leads, to allow rapid implementation.

Eleri Adams, President, British Association of Perinatal Medicine

Progress towards the national maternity safety ambition

In 2015, the Secretary of State for Health announced a national maternity safety ambition to halve the rates of stillbirths, neonatal and maternal deaths and intrapartum brain injuries by 2030, with a 20% reduction by 2020. In 2017, the date to achieve the ambition was brought forward to 2025 and the ambition was extended to include a reduction in the rate of preterm births from 8% to 6%.

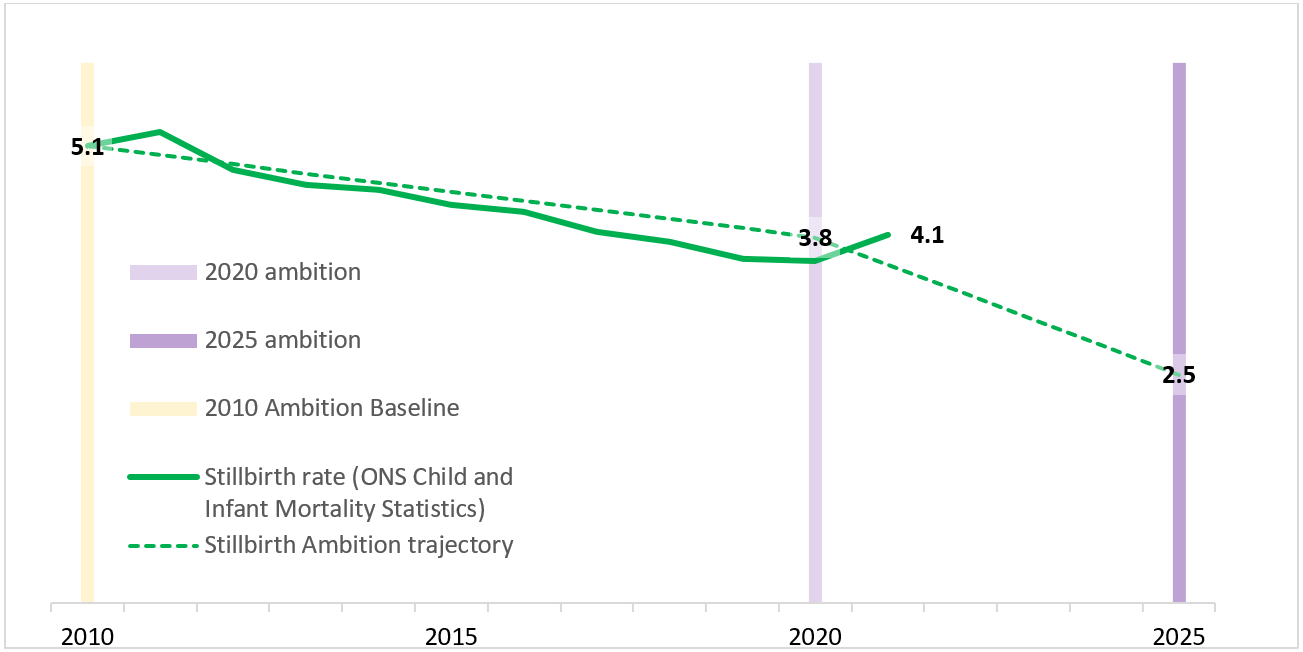

Office for National Statistics (ONS) data (shown in Figure 1 below) demonstrated a 25% reduction in stillbirths between 2010 and 2020, from 5.1 to 3.8 per 1,000 births, exceeding the 2020 milestone for stillbirths. It is not entirely clear why stillbirth rates increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is likely that the direct effects of coronavirus as well as the indirect impact of the pandemic on accessing maternity services played a part in the increase of the stillbirth rate from 3.8 per 1,000 births in 2020 to 4.1 in 2021. The neonatal mortality rate also increased between 2020 and 2021 from 1.3 to 1.4 per 1,000 live births at 24 weeks’ gestation and over. Despite the significant challenges faced by the NHS, these rates remain 19% and 30% lower respectively than in 2010. This equates to more than 900 families returning home with a healthy baby in 2021, than if the rates had not changed from 2010.

Figure 1: National maternity safety ambition – Summary of progress on stillbirths

The data on serious brain injury shows that rate of occurrence during or soon after birth fell by 9% between 2014 and 2019 to 4.25 per 1,000 live births. Further reduction is needed to meet the 2025 ambition, a rate of 2.16 per 1,000 live births.

Despite the achievements of the past few years and in light of the recent setbacks, there is clearly much more to be done to achieve the ambition by 2025. In particular, there is a need to address inequitable outcomes associated with ethnicity and deprivation. MBRRACE-UK perinatal mortality surveillance report for births in 2020 showed that the lowest stillbirth rates were for babies of White ethnicity from the least deprived areas, at 2.78 per 1,000 total births. The highest stillbirth rates were for babies of Black African and Black Caribbean ethnicity from the most deprived areas, at around 8 per 1,000 total births. The pattern is similar for neonatal deaths. Maternity services must do everything possible to mitigate the wider social determinants of health, to continue to drive down the perinatal mortality rate.

Progress of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle

The first version of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle (SBLCBv1) was published in March 2016, and focused predominantly on reducing the stillbirth rate. An independent evaluation in 2018 showed a decrease in stillbirths in participating trusts, concluding that, despite being one of many concurrent interventions, it was highly plausible that SBLCBv1 had contributed to the reduction.

The evaluation informed the development of version 2 (SBLCBv2). Launched in March 2019, SBLCBv2 aimed to go further in reducing stillbirth while also minimising unnecessary intervention. In response to the expansion of the national maternity safety ambition in 2017, it introduced Element 5 on reducing preterm birth and further decreasing perinatal mortality.

The SBLCB is now a universal innovation in the delivery of maternity care in England and continues to drive quality improvement to reduce perinatal mortality. It has been included for several years in the NHS Long Term Plan, NHS planning guidance, the Standard Contract and the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts Maternity Incentive Scheme (CNST MIS), with every maternity provider expected to have fully implemented SBLCBv2 by March 2020.

ONS and MBRRACE-UK data demonstrates the urgent need to continue reducing preventable mortality. Published 4 years after SBLCBv2, SBLCBv3 has been developed through a collaboration of frontline clinical experts, service users and key stakeholder organisations. All existing elements have been updated, incorporating learning from CNST MIS and insights from NHS England’s regional maternity teams. SBLCBv3 aligns with national guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Green Top guidelines where available but it also aims to reduce unwarranted variation where the evidence is insufficient for NICE and RCOG to provide guidance. SBLCBv3 also includes a new element on optimising care for women with pregnancies complicated by diabetes.

While SBLCBv3 would ideally be informed by the evaluation of SBLCBv2, this has been delayed due to the pandemic. Stakeholders agreed that improvements to best practice could not be delayed when evidence is readily available for improvements to several elements. The evaluation of SBLCBv2 remains a priority and will be published in 2025. Findings will inform ongoing iterations of the SBLCB.

SBLCBv3 should not be implemented in isolation, but as one of a series of important interventions to help reduce perinatal mortality, morbidity and preterm birth. It is important that providers continue to implement best practice care whenever possible, including by following NICE guidance and using the National Maternity and Neonatal Recommendations Register to assess their compliance with recommendations from confidential enquiries and other key national reports.

Implementing version 3 of the Saving Babies’ Lives Care Bundle

As part of the three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services, all NHS maternity providers have been responsible for fully implementing SBLCBv3 by March 2024.

‘Full implementation’ of the Saving Babies Lives Care Bundle means implementing all interventions for all 6 elements.

Overseeing implementation

To comply with Safety Action 6 of the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts Maternity Incentive Scheme (CNST MIS), trusts must provide assurance to their board and integrated care board (ICB) that they are on track to achieve compliance with all 6 elements of SBLCBv3, through quarterly quality improvement discussions with their ICB. Up to 3 (and at least 2) discussions should be evidenced for the relevant year, with discussions to include:

- details of element-specific improvement work being undertaken including evidence of generating and using the process and outcome metrics for each element

- progress against locally agreed improvement aims

- evidence of sustained improvement where high levels of reliability have already been achieved

- regular review of local themes and trends with regard to potential harms in each of the 6 elements

- sharing of examples and evidence of continuous learning by individual trusts with their local ICB and neighbouring trusts, publishing these on FutureNHS platform where appropriate

While the Three year delivery plan set out that SBLCBv3 should be fully implemented by March 2024, providers that have still to do so can achieve compliance with Safety Action 6 if the ICB confirms it is assured that all best endeavours – and sufficient progress – have been made towards full implementation, in line with the locally agreed improvement trajectory.

To support compliance, a national implementation tool is available for trusts to use if they wish on the FutureNHS platform. The tool can support providers to baseline current practice against SBLCBv3, agree a local improvement trajectory with their ICB and track progress locally in accordance with that trajectory. It will be updated in line with SBLCBv3.2 and existing data sets with the aim of reducing the burden of manual audits.

Trusts should be capturing SBLCB data as far as possible in their maternity information systems/electronic patient records, for submission to the Maternity Service Data Set (MSDS). A technical glossary assists MSDS v2.0 data submitters and details (where relevant) the data items, values and (where relevant) SNOMED CT terms that can be included in MSDS v2.0 submissions. Currently, some of the process and outcome indicators in the SBLCB cannot be captured in MSDS. Work is underway to integrate more process and outcome indicators as part of the development of MSDS v2.5.

Where trusts choose not to use the implementation tool to evidence compliance, they can provide a declaration signed by their executive medical director that SBLCBv3 is fully or will be in place as agreed with the ICB.

While there will be no routine, deadline-based submissions of data to the national NHS England team for the purposes of assurance, the national team will review any data stored on trust implementation tools on an ad-hoc basis to assess national progress in implementation.

Organisational roles and responsibilities

Successful implementation of SBLCBv3 requires providers, commissioners and networks to collaborate successfully. National levers, including NHS planning guidance, the NHS Standard Contract and Safety Action 6 in the CNST MIS, will be updated in to reflect the following organisational responsibilities:

- Providers are responsible for implementing SBLCBv3, including baselining current compliance, developing an improvement trajectory and reporting on implementation with their ICB as agreed locally. They are also responsible for submitting data nationally relating to key process and outcome measures for each element.

- ICBs are responsible for agreeing a local improvement trajectory with providers, along with overseeing, supporting and challenging local delivery. Where there is unresolved clinical debate about a pathway, providers may wish to agree a variation to an element of the SBLCB with their ICB. As an integral part of integrated care systems (ICSs), local maternity and neonatal systems (LMNSs) are accountable to ICBs and have the system’s maternity and neonatal expertise to support planning and provide leadership for improvement, facilitating peer support, and ensuring that learning from implementation and ongoing provision of the SBLCBv3 is shared across the system footprint.

- Clinical networks and regional maternity teams are responsible for providing support to providers, ICBs and LMNSs to enable delivery and achieve expected outcomes. It is important that specific variations from the pathways described in the SBLCBv3 are agreed as acceptable clinical practice by their clinical network.

Principles to be considered alongside implementing version 3

It has been necessary to restrict the scope of the SBLCBv3 to ensure it is deliverable. Nevertheless, it is just one of a series of important interventions to reduce perinatal mortality and preterm birth. The following principles should be considered alongside implementing the care bundle.

Promoting equity

Equity means that all groups attain the health outcomes of the most advantaged group. To help achieve equity, action must be universal but with a scale and intensity proportionate to the level of disadvantage; this is known as ‘proportionate universalism’.

While England is one of the safest countries in the world to give birth, stillbirth and neonatal mortality rates are higher for service users from Black and Asian ethnic groups and those living in the most deprived areas.

Maternity and neonatal services need to consider equity when implementing the SBLCB. They should:

- ensure that the needs of different groups are met, with support increasing as health inequalities increase. This requires use of quantitative and qualitative data about the local population and their health needs, along with co-production, to improve care pathways and implementation processes

- respond to each person’s unique health and social situation, so that care is personalised

Continuous improvement activity for each element of the SBLCB will routinely require consideration of access, experience and outcomes in relation to protected characteristics and other factors influencing inequalities, such as deprivation. Pathways and processes should be changed or additional supportive activity carried out to improve equity.

During the booking appointment, record if parents are in a close relative marriage, as this may indicate an increased risk for certain genetic conditions: while there is an increased risk of congenital anomalies in some couples, around 90% of couples remain unaffected. A detailed family history should be taken to identify potential genetic conditions and, if a potential genetic condition is identified, the antenatal screening midwife and the regional genetics service should be consulted to establish whether a referral is appropriate. Early identification empowers women to make informed reproductive choices.

To find out more, take the e-learning module Close relative marriage: equitable access to genetic information and services, which is available to all health and care staff.

MSDS consanguinity data quality guidance provides instructions on how to submit data regarding consanguinity and pregnancy to the MSDS.

Enhanced midwifery continuity of carer (EMCoC)

EMCoC remains an important intervention to address inequalities in experience and outcomes for Black and Asian women and women from economically disadvantaged groups. In line with the Core20PLUS5 strategy, local maternity and neonatal systems, regional and national colleagues will continue to support trusts with sufficient staffing to focus rollout of EMCoC to neighbourhoods with high numbers of women from Black, Asian and mixed ethnic groups and women living in deprived areas.

To support this, NHS England is providing funding to ICBs to operate EMCoC teams. Maternity services are advised to roll out these teams where safe staffing is in place, to provide improved care for women living in the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods. EMCoC teams have additional staffing to provide more holistic support for women in these areas, who are more likely to experience adverse outcomes during pregnancy and birth.

Informed choice and personalised care

Evidence shows that better outcomes and experiences, as well as reduced health inequalities, are possible when pregnant women can actively shape their care and support. Personalised care means pregnant women have choice and control over the way their care is planned and delivered, based on best available evidence, ‘what matters’ to them and their individual strengths, needs and preferences. Pregnant women receiving maternity care make informed decisions. They and their maternity professionals discuss evidence-based options together, exploring preferences, benefits, risks and consequences to enable a safe and positive experience.

For any given situation where a decision needs to be made, women are supported by their maternity professionals to understand their options and the potential benefits, harms and consequences of each. They have all the information they need for shared decision-making and give consent, in line with the Montgomery ruling.

Linked to this principle, the following areas are particularly relevant to implementing a number of elements:

Informing women of the long-term outcomes of early-term birth

One of the key interventions in Elements 2 and 3 of the SBLCBv3 is offering early birth for women at risk of stillbirth. It is important that this intervention is not extended to pregnancies that are not at risk.

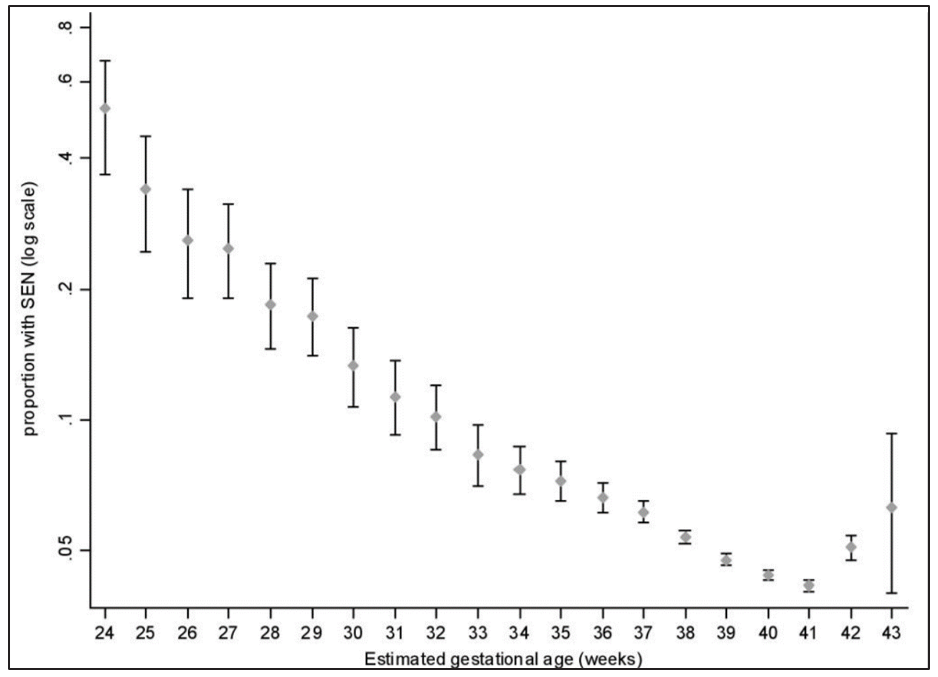

The Avoiding Term Admissions Into Neonatal units (Atain) programme identified that babies born at 37–38 weeks’ gestation were twice as likely as babies born at later gestations to be admitted to a neonatal unit. There are also concerns about long-term outcomes following early-term birth (defined as at 37–38 weeks’ gestation): These concerns relate to potential long-term adverse effects on the baby from birth before reaching maturity because, for example, the baby’s brain continues to develop at term. Birth results in huge changes to the baby’s physiology. For example, the arterial partial pressure of oxygen increases by a factor of 3 to 4 within minutes following birth and it is plausible that earlier exposure to these changes could alter long-term development of the child’s brain and data exists to support this possibility. One example is the risk that the child will subsequently have a record of special educational needs (SEN). The risk of this outcome is about 50% among infants born at 24 weeks of gestational age and it progressively falls with increasing gestational age at birth, only to bottom out at around 40–41 weeks.

Figure 2: Prevalence of special educational needs by gestation at birth

After adjusting for maternal and obstetric characteristics and expressed relative to birth at 40 weeks, the risk of SEN was increased by 36% [95% CI (confidence interval) 27–45] at 37 weeks, by 19% (95% CI 14–25) at 38 weeks and by 9% (95% CI 4–14) at 39 weeks. The risk of subsequent SEN was 4.4% at 40 weeks. Hence, assuming causality, there would be one additional child with SEN for every 60 inductions at 37 weeks, for every 120 inductions at 38 weeks and for every 250 inductions at 39 weeks compared with the assumption that they would otherwise have been born at 40 weeks. Recent data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study confirmed the finding that children born at early-term gestational ages (37–38 weeks) were more likely not to achieve the expected level of attainment in primary school but, interestingly, there was no association between early-term birth and poorer attainment at secondary school. Moreover, as the current data is based on the observed gestational age at birth, the negative associations with later outcome may be explained by the factors that determined early-term birth rather than a direct effect of gestational age. However, induction of labour before 39 weeks should continue to be considered as a significant medical intervention that requires appropriate justification.

Considering how the risks of induction of labour change with gestational age

For uncomplicated pregnancies NICE guidance on induction of labour should be followed. In all cases of induction, it is important that women are given a clear explanation of why they are being offered induction and that the risks, benefits and alternatives are discussed.

At 39+0 weeks’ gestation and beyond, induction of labour is not associated with an increase in caesarean section, instrumental vaginal birth, fetal morbidity or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. The NICE guidance and data from the ARRIVE study provide contradictory evidence as to whether induced labours are associated with a longer hospital stay or more painful labours. Induction of labour may also increase the workload of the maternity service, which has the potential to impact on the care of other women.

Safe and healthy pregnancy information to enable women and their families to make informed choices

It is important that women have access to high quality information before and during their pregnancy to enable them to reduce risks to their baby. The Office for Health Inequalities and Disparities and Sands have developed key messages:

Summary of safe and healthy pregnancy key messages

Pre-pregnancy:

- choose when to start or grow your family by using contraception

- consult with your GP if taking medication for long-term conditions (for example, diabetes, hypertension, epilepsy) as your medication may have to change prior to pregnancy

- eat a healthy balanced diet and be physically active to enter pregnancy at a healthy weight

- take a daily supplement of 400 micrograms (400 µg) folic acid before conception (some women will require a higher dose of 5 mg as advised by a healthcare professional)

- ensure that you are up to date with routine vaccinations, for example measles, rubella, coronavirus (COVID-19), flu

- find out if you think you or your partner could be a carrier for a genetic disorder

- stop smoking and/or exposure to second-hand smoke

- reduce/stop alcohol consumption

During pregnancy:

- continue to take 400 µg folic acid until the 12th week of pregnancy (some women will require a higher dose of 5 mg as advised by a healthcare professional)

- pregnant women should have 10 µg of vitamin D a day

- you may be advised to take aspirin from 12 weeks of pregnancy

- alcohol – the safest advice is to not drink alcohol; if you are concerned, talk to your midwife or doctor, and help and advice is available for you

- don’t smoke and avoid second-hand smoke; support is available to help with this

- do tell your midwife if you use illegal street drugs or other substances; help is available for you.

- eat healthily and be physically active to maintain a healthy weight while pregnant

- maintain oral hygiene. Free dental care is available to all pregnant women and up to a year after the birth

- recommended vaccinations and boosters: seasonal flu, pertussis (whooping cough), coronavirus (COVID-19)

- always check with your pharmacist, midwife or doctor about medicines and therapies used in pregnancy, even if you have taken them for a long time on prescription or think they are harmless

- avoid contact with people who have infectious illnesses, including diarrhoea, sickness, childhood illnesses or any rash-like illness

- reduce the risk of cytomegalovirus, toxoplasmosis, Mpox infections, etc

- attend all antenatal appointments

- contact the maternity service promptly if you are worried about reduced fetal movements, vaginal bleeding, watery or unusual discharge, signs of pre-eclampsia or itching. Don’t wait!

- in later pregnancy (after 28 weeks), it is safer to go to sleep on your side than on your back

More detailed information on how women can plan, prepare, and look after themselves before and during pregnancy can be found on NHS.uk and the Safer Pregnancy website developed by Sands.

Working within networks for more specialist care

In several specialist fields, maternity services are working within networks so that women and babies with complex needs have consistent access to the most specialist care, while also encouraging local expertise and ensuring that care remains as close as possible to home.

While a networked model has been in place for a number of years in fetal medicine and in neonatal care, NHS England announced the creation of 14 maternal medicine networks, which are now in operation across England.

All providers should be engaging in these networks and contributing to the development of joint protocols and ways of working. In this vein, new elements of best practice should not be implemented in isolation locally. Providers should consider what implications or opportunities this presents for ways of working agreed within wider maternal medicine, fetal medicine or neonatal operational delivery networks.

Implementing relevant NICE guidance

Integrated care systems (ICSs)/ICBs are under an obligation in public law to have regard for NICE guidance and to provide clear reasons for any general policy that does not follow NICE guidance.

Providers and commissioners are encouraged to implement NICE guidance relating to antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care. In particular, implementation of the NICE guidance on the management of diabetes in pregnancy, hypertension in pregnancy, multiple pregnancy and service provision for women with complex social factors is key to addressing some of the most significant contributors to perinatal mortality.

Best practice care in the event of a stillbirth or neonatal death

Despite the reduction in stillbirth rates sadly thousands of parents each year will experience the devastation of their baby dying before, during or shortly after birth. A best practice pathway for the clinical management of women experiencing stillbirth is available on the North West Coast (NWC) Strategic Clinical Network website.

Sands has developed a National Bereavement Care Pathway (NBCP) to help ensure that all bereaved parents are offered equal, high quality, individualised, safe and sensitive bereavement care when they experience pregnancy loss or the death of a baby.

The national Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT) is used to support hospital reviews by providing a standardised, structured process so that what happened at every stage of the pregnancy, birth and after, from booking through to bereavement care, is carefully considered by staff reviewing care. This online tool may help staff understand why a baby has died and whether there are any lessons to be learned to save lives in future.

Continuous improvement and maternity and neonatal services

SBLCBv3 maintains the continuous improvement approach. Each element focuses on a small number of outcomes, now with fewer process measures. Implementation of the elements will require a more comprehensive evaluation of each organisation’s processes and pathways and an understanding of where improvements can be made.

Each organisation will be expected to look at its performance against the outcome measures for each element with a view to understanding where improvement may be required. We have provided suggested areas for improvement in each element, but these lists are not meant to be exhaustive.

There is an expectation that as well as organisations reporting on their implementation of each element, there will be complimentary reporting of ongoing improvement work (with associated detail of interventions and improvement in process measures and outcomes) for each element. An integral component of this improvement work will be a focus on learning from incidents or enquiry. Harm may have occurred in relation to implementation of or non-compliance with an element of the SBLCB. The use of the Perinatal Mortality Review Tool will complement the investigation and learning in this context.

Element 1: Reducing smoking in pregnancy

Element description

Reducing smoking in pregnancy by identifying smokers with the assistance of carbon monoxide (CO) testing and ensuring in-house treatment from a trained tobacco dependence adviser (TDA)* is offered to all pregnant women who smoke, using an opt-out referral process.

*The TDA role is also known under alternative names, including smoking cessation adviser, stop smoking adviser and smoking cessation practitioner. Irrespective of role name or grade, this role is underpinned by appropriate training to deliver tobacco dependence treatment interventions (see 1.10).

Interventions

1.1 CO testing offered to all pregnant women at the antenatal booking and 36-week antenatal appointment.

1.2 CO testing offered at all other antenatal appointments to groups identified in NICE guidance [NG209].

1.3 Whenever CO testing is offered, it should be followed up with an enquiry about smoking status with the CO result and smoking status recorded.

1.4 Instigate an opt-out referral for all women who have an elevated CO level (4 ppm or above), who identify themselves as smokers or who have quit in the last 2 weeks for treatment by a trained TDA within an in-house tobacco dependence treatment service.

1.5 Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) should be offered to all smokers and provision ensured as soon as possible.

1.6 The tobacco dependence treatment includes behavioural support and NRT, initially 4 weekly sessions following the setting of the quit date then regularly (as required, however as a minimum monthly) throughout pregnancy to support the woman to remain smokefree.

1.7 Feedback is provided to the pregnant woman’s named maternity healthcare professional regarding the treatment plan and progress with their quit attempt (including relapse). Where a woman does not book or attend appointments there should be immediate notification back to the named maternity healthcare professional.

1.8 Any staff member using a CO monitor should have appropriate training on its use and discussion of the result.

1.9 All staff providing maternity care to pregnant women should receive training in the delivery of very brief advice (VBA) about smoking, making an opt-out referral and the processes within their maternity pathway (for example, referral, feedback, data collection).

1.10 Individuals delivering tobacco dependence treatment interventions should be fully trained to National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT) standards.

Continuous Learning

1.11 When analysing patient safety incidents, maternity care providers should review smoking status throughout pregnancy and determine whether the appropriate pathway of care for this was followed.

1.12 Maternity providers should regularly review (a minimum of quarterly) their smoking-related data to understand performance and develop improvement plans (this list is designed to provide a steer and is not exhaustive):

a. Identification of women who smoke – determine any factors that would optimise CO testing rates and enquiry about smoking status from both the provider/pathway and service-user perspective and make changes to pathways and processes as appropriate.

b. Training of staff – ensure all staff involved in identification, referral and treatment of women who smoke and provision of VBA are appropriately trained.

c. Engagement – determine and address any barriers to engagement with treatment services or compliance with treatment interventions from both the provider/pathway and service-user perspective.

d. Referral – determine and address any factors that are influencing opt-out referral from both the provider/pathway and service-user perspective.

e. Quit rates – consider the pathway holistically to determine which steps can be optimised to facilitate quit attempts and successful quits.

f. Relapse – determine factors that are contributing to relapse and whether additional support or changes to pathways may address these.

g. Inequalities – consider all the above by protected characteristics and other variables influencing inequalities, such as factors related to deprivation. Make changes to pathways and processes, or carry out additional supportive activity, to address any inequity or inequalities identified.

1.13 To monitor quality and effectiveness of pathways, maternity services should set ambitions for their pathway with regular review (a minimum of quarterly) of data and targeted quality improvement work to ensure they are being achieved.

1.14 Based on highly performing areas, stretching ambitions to achieve effective implementation of the full element may include:

a. 95% of women where CO measurement and smoking status is recorded at their booking appointment

b. 95% of women where CO measurement and smoking status is recorded at their 36-week appointment

c. 95% of smokers have an opt-out referral at booking for treatment by a TDA within an in-house service

d. 85% of all women referred for tobacco dependence treatment engage with the programme (have at least one session and receive a treatment plan)

e. 60% of those referred for tobacco dependence treatment set a quit date

f. 60% of those setting a quit date successfully quit at 4 weeks

g. At least 85% of quitters should be CO verified

1.15 Individual providers should examine their outcomes in relation to other providers or systems with similar smoking prevalence or populations. National benchmarking is available through the Maternity Services Dashboard and will be available to ICS/LMNS as the tobacco dependence patient-level collection is established.

Process Indicators

1a. Percentage of women where there is a record of:

i. CO measurement at booking appointmen

ii. CO measurement at 36-week appointment

iii. smoking status** at booking appointment

iv. smoking status** at 36-week appointment

1b. Percentage of smokers* who have an opt-out referral at booking to an in-house / in-reach tobacco dependence treatment service.

1c. Percentage of smokers* who are referred for tobacco dependence treatment who set a quit date.

Outcome Indicators

1d. Percentage of smokers* at antenatal booking who are identified as CO verified non-smokers at 36 weeks.

1e. Percentage of smokers* who set a quit date and are identified as CO verified non-smokers at 4 weeks.

*A ‘smoker’ is a pregnant woman with an elevated CO level (≥4 ppm) and identifies themselves as a smoker (smoked within the last 14 days) or has a CO level <4 ppm but identifies as a smoker (smoked within the last 14 days).

**Smoking status relates to the outcome of the CO test (>4 ppm) and the enquiry about smoking habits.

Rationale

Smoking increases the risk of pregnancy complications, such as stillbirth, preterm birth, miscarriage, low birthweight and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Whether or not a woman smokes during her pregnancy has a far-reaching impact on the health of a child throughout their life. Studies have found that the risk of a number of poor pregnancy outcomes can be reduced to that of a non-smoker if a successful quit is achieved early in pregnancy. Others show increased risk with any smoking in pregnancy and increasing risk with continued smoking. This reinforces the need to support women to quit smoking as early as possible in pregnancy to reduce the risk of poor pregnancy outcomes.

Smoking at time of delivery (SATOD) rates have declined since the release of previous versions of the SBLCB, albeit at a slower rate than required to meet the government’s 2022 national ambition of 6% (and ultimately a smokefree generation by 2030). Although there is significant variation, the national SATOD rate was 9.1% in 2021/22, demonstrating that further work is required to reduce smoking during pregnancy.

This element is evidence based and provides a practical approach incorporating the NHS Long Term Plan pathway for a smokefree pregnancy and core elements of NICE guidance. It builds on the previous version of the SBLCB’s focus on CO testing to support identification of smokers, with referral to in-house tobacco dependence treatment services and ensuring that effective treatment is available to all pregnant women who smoke. Research indicates that pregnant women expect their maternity provider to ask about smoking and if the issue is not raised, this can be incorrectly interpreted as smoking not being a problem for the pregnancy. Learning from frontline services demonstrates a need for a treatment offer that is part of the maternity pathway and the woman’s maternity journey. This should include processes for referral, treatment and feedback that are timely and optimise engagement, with dedicated leadership within the maternity service that has oversight of the full pathway. To support this, all clinicians with whom the woman comes into contact during pregnancy should give consistent messages.

This element has a positive impact on the other SBLCB elements. Reducing smoking in pregnancy will reduce instances of fetal growth restriction, intrapartum complications and preterm birth. This demonstrates the complementary and cumulative nature of the SBLCB approach.

This element also reflects the wider prevention agenda, impacting positively on the health of babies and the long-term outcomes for families and society.

Implementation guidance

Key factors for effective implementation include:

In-house pathways: Clinical leadership, delivery and oversight of the service and its outcomes remains with maternity. Services are considered as in-house when the woman’s care for treating their tobacco dependence remains within the maternity service – that is, is not referred out to another provider like a local authority stop smoking service.*

* In-reach services where a third party, such as the local authority stop smoking service, provide services as part of the maternity team with the patient staying under the care and management of the maternity service would count as in-house.

Opt-out referral pathways: Effective pathways are in place to ensure that as soon as a smoker is identified there is rapid referral to the TDA on an opt-out basis. Immediate referral and consultation with the TDA is the ideal, but as a minimum the woman should be contacted within 1 working day and seen (ideally face to face) by a TDA within 5 working days.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT): Pathways should ensure provision of long and short-acting NRT at the earliest opportunity to facilitate quitting at an optimal time to improve perinatal outcomes and maximise engagement with referral and treatment services. Ideally, this should be at the earliest opportunity when maternity care has started, even if prior to a formal booking appointment.

Recent quitters: The definition of a smoker includes those who have smoked within the past 2 weeks. However, it is good clinical practice to offer support to all women who have quit smoking since conception given that changes in 1st trimester pregnancy symptoms may affect smoking habits.

CO testing: All pregnant women should be offered CO testing at the antenatal booking and 36-week antenatal appointment, with testing offered at all other antenatal appointments after booking to groups identified within NICE guidance [NG209]. All staff providing antenatal care should have access to a CO monitor and training in how to use it and interpretation of results. Appropriate procurement processes should be in place for obtaining CO monitors and associated consumables (for example, tubes and batteries).

CO verified non-smokers at 4 weeks: This corresponds to the 4-week quit that is regularly captured by stop smoking services and is a comparable indicator that can be used to assess the quality of the intervention.

CO levels: The most common reason for a raised CO level is smoking. However exposure may come from other sources such as second-hand smoke, faulty boilers, faulty heating/cooking appliances or car exhausts (and can happen at home or at the workplace). If women have raised CO levels and are non-smokers, environmental exposure from a source in the home should be considered and the women should be advised to contact the Gas Emergency Line on 0800 111 999 for further advice. Referral for further medical advice should be sought if symptoms are consistent with CO poisoning. For NICE guidance on air pollution and vulnerable groups, see recommendation 1.7.7. in NICE guidance [NG70].

Tobacco dependence treatment: Following an initial appointment where a quit is initiated, weekly face-to-face appointments with the TDA should take place for at least 4 weeks after the quit date is set, followed by regular appointments (as required but monthly as a minimum) throughout the pregnancy. Treatment includes behavioural support and a combination of long and short-acting NRT. A recommended delivery model pathway is available on the Prevention Programme’s FutureNHS webpages.

Recording data: There should be routine recording of the CO test result and smoking status for each pregnant woman on maternity information systems (MIS), reporting through to the tobacco dependence patient-level collection and, where appropriate, the Maternity Service Data Set (MSDS).

Review and act on local data: Use available tools (for example, the Maternity Services Dashboard’s clinical quality improvement metrics) to review the current situation with smoking and data quality, compare with other nearby or demographically similar trusts and identify if your trust is an outlier and/or where improvements can be made.

Vaping: In its position statement on support to quit smoking in pregnancy, the Royal College of Midwives states that “E-cigarettes contain some toxins, but at far lower levels than found in tobacco smoke. If a pregnant woman and birthing person who has been smoking chooses to use an e-cigarette (vaping) and it helps her to quit smoking and stay smokefree, she should be supported to do so”. More information is available via the Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group.

System-wide action: Action to help pregnant women stop smoking should be supplemented by wider activity across the local system to reduce smoking rates among women, partners and other household or family members. This includes reducing smoking rates in women pre-conception, in addition to working with neonatal care and health visiting services to ensure there are links with local stop smoking services to support quitting postnatally. Local tobacco control networks alongside LMNSs, ICSs and regional teams should be able to support with integrating activity to reduce smoking prevalence in all population groups, which can impact on reducing maternal smoking.

Implementation resources

Resources: The NHS Long Term Plan delivery model for smokefree pregnancy provides details of the pathway and treatment programme that should be delivered in this element. This can be found on the FutureNHS webpages with additional resources and shared materials.

Information and links to further resources are also available from the Maternal and Neonatal Health Safety Collaborative. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) produces annual briefings for ICSs showing the impact of smoking, using data at ICS level. The briefings include national data on maternal smoking and other clinical areas broken down to ICS level, and signpost to current resources and information.

The Smoking in Pregnancy Challenge Group produces a range of resources and information for healthcare professionals working to reduce maternal smoking. Those with an interest can also join the Smokefree Pregnancy Information Network administered by ASH, which will provide up to date information throughout the year. For more information contact admin@smokefreeaction.org.uk.

Training – tobacco dependence adviser: Those providing tobacco dependence treatment interventions are specialist advisers and should have successfully completed NCSCT smoking practitioner training (or local training to the to the required NCSCT standard) and a speciality course for smoking in pregnancy (requires registration and log-in), including opportunities to observe good practice; to ensure they have the knowledge and skills to deliver the treatment. TDAs should receive annual refresher training. NCSCT-derived competency frameworks are also available on the FutureNHS platform.

Training – all maternity healthcare professionals: All multidisciplinary staff providing maternity care for pregnant women should receive training on how to use a CO monitor (see CO testing section), the delivery of very brief advice (VBA) about smoking, making an opt-out referral and the processes within their maternity pathway (for example, referral, feedback, data collection). Annual refresher training should align with the core competency framework. VBA on smoking in pregnancy training can be accessed via NCSCT e-learning or eLearning for Health Hub.

Element 2: Fetal growth: risk assessment, surveillance and management

Element description

Risk assessment and management of babies at risk of or with fetal growth restriction (FGR).

Interventions

Reduce the risk of FGR where possible.

2.1 Assess all women at booking to determine if prescription of aspirin is needed using an appropriate algorithm (for example, Appendix B) agreed with the local ICSs and regional maternity team.

2.2 Recommend vitamin D supplementation to all pregnant women.

2.3 Assess smoking status and manage findings as per Element 1.

Monitor and review the risk of FGR throughout pregnancy.

2.4 Perform a risk assessment for FGR by 14 weeks’ gestation using an agreed pathway (for example, Appendix C). Risk assessment in multiparous women should include the calculation of previous birthweight centiles. If a woman is a late booker or transfer of care, then a risk assessment should be completed using the risk assessment system of the new location trust. The pathway and centile calculator used should be agreed by both the local ICSs and the regional maternity team.

2.5 During risk assessment trusts are encouraged to use information technology platforms to facilitate accurate recording and correct classification of risk by staff. No single provider is recommended, but technology platforms should not prevent compliance with Element 2 guidance and should follow national recommendations on the use of fundal height and fetal growth charts.

2.6 As part of the risk assessment for FGR, blood pressure should be recorded using a digital monitor that has been validated for use in pregnancy (see ‘Implementation’ below).

2.7 Women who are designated as high risk for FGR (for example, see Appendix C) should undergo uterine artery Doppler assessment between 18+0 and 23+6 weeks’ gestation.

2.8 The risk of FGR should be reviewed throughout pregnancy and maternity providers should ensure that processes are in place to enable the movement of women between risk pathways dependent on current risk.

2.9 When an ultrasound-based assessment of fetal growth is performed, trusts should ensure that robust processes are in place to review which risk pathway a woman is on and agree a plan of ongoing care.

2.10 Women who are at low risk of FGR should have serial measurement of symphysis fundal height (SFH) at each antenatal appointment after 24+0 weeks’ gestation (no more frequently than every 2 weeks). The first measurement should be carried out by 28+6 weeks. Measurements should be plotted or recorded on charts by clinicians trained in their use.

2.11 Staff who perform SFH measurement should be competent in measuring, plotting (or recording), interpreting appropriately and referring when indicated. Only staff who perform SFH measurement need to undergo training in SFH measurement.

2.12 Women who are undergoing planned serial scan surveillance should cease SFH measurement after serial surveillance begins. SFH measurement should also cease if women are moved onto a scan surveillance pathway in later pregnancy for a developing pregnancy risk (for example, late-onset FGR).

2.13 Women who are at increased risk of FGR should have ultrasound surveillance of fetal growth at 3–4-weekly intervals until delivery (see RCOG guidance and Appendix C).

Provide the correct surveillance when FGR is suspected and delivery at the right time.

2.14 When FGR is suspected an assessment of fetal wellbeing should be made including a discussion regarding fetal movements (see Element 3) and if required computerised cardiotocograph (cCTG). A maternal assessment should be performed at each contact this should include blood pressure measurement using a digital monitor that has been validated for use in pregnancy and a urine dipstick assessment for proteinuria. In the presence of hypertension NICE guidance on the use of PlGF/sflt1 testing should be followed.

2.15 Umbilical artery Doppler is the primary surveillance tool for FGR identified prior to 34+0 weeks and should be performed as a minimum every 2 weeks. Maternity care providers caring for women with early FGR identified prior to 34+0 weeks’ gestation should have an agreed pathway for management that includes fetal medicine network input (for example, through referral or case discussion by phone). Further information is provided in Appendix C.

2.16 When FGR is suspected, the frequency of review of estimated fetal weight (EFW) should follow the guidance in Appendix C or an alternative that has been agreed with local ICSs following advice from the provider’s clinical network and/or regional team.

2.17 Risk assessment and management of growth disorders in multiple pregnancy should comply with NICE guidance or a variant that must be agreed by both the local ICSs and the regional maternity team.

2.18 All management decisions regarding the timing of FGR infants and the relative risks and benefits of iatrogenic delivery should be discussed and agreed with the mother. When the EFW is <3rd centile and there are no other risk factors (see 2.20), initiation of labour and/or delivery should occur at 37+0 weeks’ gestation and no later than 37+6 weeks’ gestation.

2.19 In fetuses with an EFW between the 3rd and <10th centile, delivery should be considered at 39+0 weeks’ gestation. Birth should be achieved by 39+6 weeks’ gestation. Other risk factors should be present for birth to be recommended prior to 39 weeks (see 2.20).

2.20 Fetuses who demonstrate declining growth velocity from 32 weeks’ gestation are at increased risk of stillbirth from late-onset FGR. Declining growth velocity can occur in fetuses with an EFW >10th centile. Evidence to guide practice is limited and guidance (see Appendix C) is currently based on consensus opinion. In fetuses with declining growth velocity and EFW >10th centile, the risk of stillbirth from late-onset FGR should be balanced against the risk of late preterm delivery. In infants where declining growth velocity meets criteria (see Appendix C), delivery should be planned from 37+0 weeks’ gestation unless other risk factors are present. Risk factors that should trigger review of timing of birth are: reduced fetal movements, any umbilical artery or middle cerebral artery Doppler abnormality, cCTG that does not meet criteria, maternal hypertensive disease, abnormal sFlt1: PlGF ratio/free PlGF or reduced liquor volume. Opinion on timing of birth for these infants should be made in consultation with specialist fetal growth services or fetal medicine services depending on trust availability.

Continuous learning

Learning from excellence and error or incidents

2.21 Trusts should determine and act on all themes related to FGR that are identified from investigation of incidents, perinatal reviews and examples of excellence.

2.22 Trusts should provide data relating to the following to their boards and share this with their ICS:

a. percentage of babies born <3rd birthweight centile >37+6 weeks’ gestation

b. ongoing case note audit of <3rd birthweight centile babies not detected antenatally and born after 38+0 weeks’ gestation, to identify areas for future improvement (at least 20 cases per year or all cases if fewer than 20 occur)

c. percentage of babies born >39+6 and <10th birthweight centile to provide an indication of detection rates and management of small for gestational age (SGA) babies

d. percentage of babies >3rd birthweight centile born <39+0 weeks’ gestation

2.23 Use the Perinatal Mortality Review Tool (PMRT) to calculate the percentage of perinatal mortality cases annually where the identification and management of FGR was a relevant issue. Trusts should review their annual MBRRACE perinatal mortality report and report to their ICS on actions taken to address any identified deficiencies.

2.24 Individual trusts should examine their outcomes in relation to similar trusts to understand variation and inform potential improvements.

2.25 Individual trusts should provide data on the distribution of FGR outcomes with relation to maternal reported ethnicity.

2.26 Maternity providers are encouraged to focus improvement in the following areas:

a. appropriate risk assessment for FGR and other conditions associated with placental dysfunction and robust referral processes to appropriate care pathways following this

b. appropriate prescribing of aspirin in line with this risk assessment in women at risk of placental dysfunction

c. review of ultrasound measurement quality control. Trusts are encouraged to comply with British Medical Ultrasound Society (BMUS) guidance on audit and continuous learning with relation to 3rd trimester assessment of fetal wellbeing

d. Trusts will share evidence of these improvements with their board and ICS and demonstrated continuous improvement in relation to process and outcome measures

Process indicators

2a. Percentage of pregnancies where a risk status for FGR is identified and recorded at booking. (This should be recorded on the provider’s maternity information system (MIS) and included in the MSDS submission to NHS England once the primary data standard is in place.)

2b. Percentage of pregnancies where an SGA fetus (between 3rd and <10th centiles) is detected antenatally and this is recorded on the provider’s MIS and included in its MSDS submission to NHS England.

2c. Percentage of perinatal mortality cases annually where the identification and management of FGR was a relevant issue (using the PMRT).

Outcome indicators

2d. Percentage of babies <3rd birthweight centile born >37+6 weeks’ gestation (this is a measure of the effective detection and management of FGR).

Rationale

There is strong evidence linking undiagnosed FGR to stillbirth. Therefore, antenatal detection of growth restricted babies is vital and has been shown to reduce stillbirth risk significantly because it gives the option to consider timely delivery of the baby.

Update for version 3

The previous versions of this element have made a measurable difference to antenatal detection of FGR across England. Version 2 resulted in the widespread uptake of uterine artery Doppler screening for the first time outside tertiary centres in England and a significant improvement in the quality of care provided to pregnant women in all types of maternity setting. By introducing more nuanced risk assessment we have sought to reduce intervention while maintaining the focus on delivering babies at risk. In this version we seek to clarify this further so that all members of staff caring for pregnant women have clear, practical guidance. Our new title – Fetal growth: risk assessment, surveillance and management – reflects this.

Important changes in this update are:

- following a review by the Chief Scientific Officer team, only digital measurement of blood pressure is now recommended for risk assessment and monitoring of FGR

- The previous definition of suboptimal fetal growth of <20 g/day in the late 3rd trimester has been too didactically interpreted and has therefore been removed. A prospectively tested method of identifying suboptimal fetal growth in babies >10th centile remains elusive so suggestion for replacement is contained within Appendix C

- RCOG guidance on fundal height and EFW charts is still awaited so trusts may continue to use a range of charts. However, charts that are appropriate for plotting EFW and birthweight are recommended for reporting to reduce discrepancies

Risks and benefits of early-term delivery

It is well recognised that preterm birth is associated with both short and long-term sequelae for the infant. The distinction between preterm and term birth is based on the 37+0-week threshold. However, like any threshold on a continuous scale, the separation into 2 groups is arbitrary. Some of the risks associated with preterm birth are still apparent at ‘early-term’ gestation, defined as 37 and 38 weeks. The association with short-term morbidity can be captured by analysing the risk of admission of the infant to the neonatal unit. One of the best UK analyses compared the risk of neonatal unit admission associated with induction of labour at the given week with the comparison group of all women delivered at a later week of gestation (Table 1).

Table 1: Neonatal unit admission according to week of gestational age, comparing induction of labour and expectant management

|

Week of gestational age | Neonatal admission per 1,000 |

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|

|

Induction of labour |

Delivered later |

|

|

37 |

176 |

78 |

2.01 (1.80–2.25) |

|

38 |

113 |

74 |

1.53 (1.41–1.67) |

|

39 |

93 |

73 |

1.17 (1.07–1.20) |

|

40 |

80 |

73 |

1.14 (1.09–1.20) |

|

41 |

66 |

84 |

0.99 (0.93–1.05) |