Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) are a critical component of the urgent and emergency care system. They respond to those patients most in need of acute NHS care, often at points of crisis in their lives, and play an important role in shaping public perception about how the NHS is faring.

The challenges facing EDs today should be well understood, with demand outstripping capacity, long wait times and overcrowded departments. Poor hospital flow results in the unacceptable experiences of corridor care and ambulance delays. This, in turn, leads to delay-related harm – often to our most vulnerable patients – and a poor working environment for staff.

High-performing urgent and emergency care pathways depend on the whole system working effectively around the clock, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Additional guidance will follow to set out how different components of the wider urgent and emergency care (UEC) system should support improvements in flow, including:

- urgent community services

- standards for the first 72 hours of hospital care

- 7-day working standards

- mental health EDs

- the development of neighbourhood health

- specific work on frailty and children and young people (CYP) pathways

This will help to establish the ED as a ‘destination rather than a default’, with patients directed earlier in their pathway to the most appropriate care for their needs. This should form part of an overall system effort to improve urgent and emergency care performance towards the constitutional pledge that at least 95% of patients attending A&E should be admitted, transferred, or discharged within 4 hours of arrival.

The purpose of this publication is to:

- focus on elements within the ED’s control

- set out opportunities for good practice in internal ED pathways

This publication should be read in conjunction with other guidance involving all elements of the UEC pathway.

This guidance applies to all age groups, ensuring that the needs of adults and children and young people are appropriately considered within ED pathways.

The principles of clinical care within an emergency department

There are 5 key principles:

- the ED must be prioritised for those patients who are in most need of emergency medical care

- overcrowding increases risk in the ED environment, making it harder to identify and clinically prioritise the sickest patients and those with vulnerabilities (for example, frail, newborns, those with learning difficulties or mental health conditions)

- overcrowding also increases the inefficiency within UEC pathways, driving up staffing levels and pressures, and causing more delays

- patients requiring emergency medical care, whether to be admitted or discharged from the ED, should receive care in an appropriate setting and not be put at risk of delay-related harm with undue waits for investigation, treatment, specialty care or admission

- the ED team cannot deliver effective and high-quality care without engagement and leadership from the whole hospital and effective patient flow and discharge pathways from all specialty teams

The patient’s perspective

Feedback from patient groups and previous patient engagement exercises (that is, London’s ‘dialogue and deliberation’ exercise and the patient attitudes survey) have highlighted the following among patient priorities when receiving emergency or urgent care.

Reassurance from clinicians

Patients most want reassurance; they want to know they’re not dying and that they will receive care and support.

From this, we learnt that information should be effectively transferred between clinicians and to patients in a compassionate and transparent way.

Receiving extended treatment away from ED

Patients prefer to receive extended periods of treatment away from the stress of ED.

From this, we learnt we should maximise use of same day emergency care (SDEC) and extended emergency medicine ambulatory care (EEMAC) areas.

Access to timely information

Patients want to know what’s going on – before, during and after care.

From this, we learnt we should share information on wait times and next steps within extended care areas.

Not waiting for a bed

Patients don’t want to wait for long periods in ED before they’re admitted to a bed.

From this, we learnt we should prioritise improving flow and reducing bed occupancy.

It is important to note that children and young people and those with frailty may have different needs and experiences that must also be taken into account (see further considerations for children and young people in appendix 1).

Recommended elements of the emergency department

To meet these principles and deliver care that matches patient needs, it is important we work to ensure the ED has adequate facilities to assess and manage emergency patients – those who require the skills of the emergency physician and the resources of an ED.

By using potential areas of care according to demand, we can help ensure that patients who need the specific skills of emergency medicine are prioritised for this care.

In EDs that see adults, children and young people, it is essential that the commissioning, design and layout support the needs of all groups equitably.

Some departments will be providing patient care under the same principles but not in the exact configurations described; this publication is not intended to disrupt these pathways.

Not all the recommended elements of this publication will be immediately available or necessary for existing departments, and some departments may deliver the standards of care through different pathways. However, it is expected that the principles of this document should form part of the ongoing improvement strategy for emergency care within a trust.

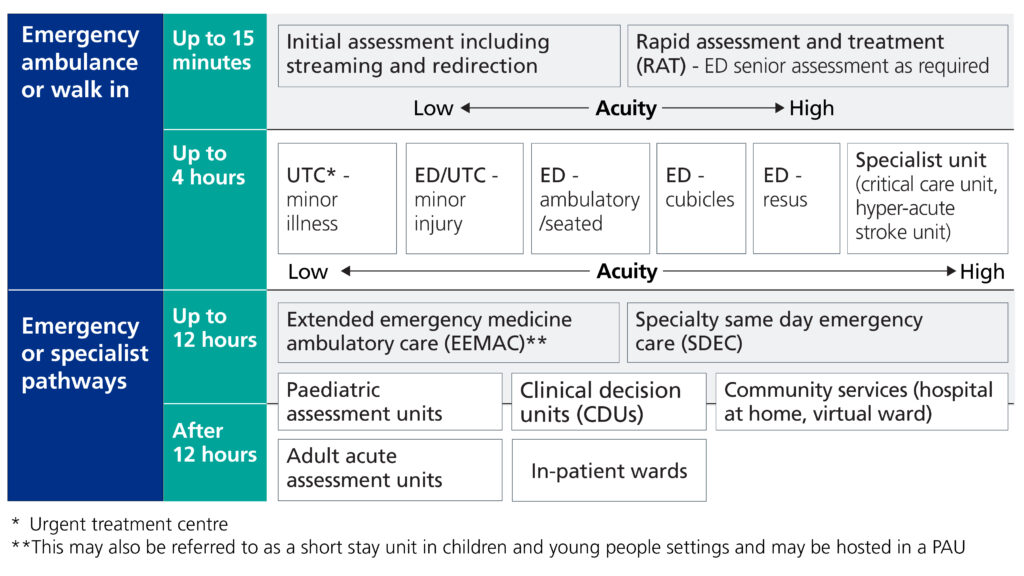

Emergency and urgent care pathways by acuity and time

Image text:

Emergency ambulance or walk in

Up to 15 minutes

A horizontal acuity scale runs from low to high:

- low acuity: initial assessment including streaming and redirection

- high acuity: rapid assessment and treatment (RAT) – ED senior assessment as required

Up to 4 hours

A horizontal acuity scale runs from low to high. Services are arranged in order of increasing acuity:

- lowest acuity: urgent treatment centre (UTC) – minor illness

- ED/UTC – minor injury

- ED – ambulatory/seated

- ED – cubicles

- highest acuity: ED – resus

Emergency or specialist pathways

Up to 12 hours:

- extended emergency medicine ambulatory care (EEMAC)*

- specialty same day emergency care (SDEC)

Shown as between up to 12 hours and after 12 hours:

- paediatric assessment units (PAU)

- clinical decision units (CDUs)

- community services (hospital at home, virtual ward)

After 12 hours:

- adult acute assessment units

- specialist unit (critical care unit, hyper-acute stroke unit)

- inpatient wards

*This may also be referred to as a short stay unit in children and young people settings and may be hosted in a PAU.

The emergency department – key elements to support care

Single point of access (pre-hospital)

Early clinical support for patients with urgent and emergency care needs, including those in care homes or other community settings, can be beneficial. ED clinicians involved in these services are also often involved in recognising the care needs of high-intensity users of the health service.

Systems and trusts should recognise and support ED clinicians undertaking these roles. This includes supporting clinicians to provide specialist advice regarding frail patients or young infants, for example.

Front door streaming, triage and redirecting patients requiring urgent care

Patients typically present at, or are brought to, the ED either through ‘walk-in’ pathways or by ambulance. These patients then require an initial assessment to prioritise their care and determine the best area where this care can be provided.

Patients requiring the care of the ED should be immediately streamed to that area, while patients who do not need this level of care should be streamed to an urgent treatment centre (UTC) or minor illness or injury area, ideally co-located (a short walking distance between departments) with the ED. This must apply to all ages, including children and young people.

It is recognised that some departments will be using redirection to off-site units, and these should continue as appropriate – but the principle should be that only those patients who need emergency care should remain in the ED.

Referrals from healthcare professionals that require the skills of emergency medicine will go to the ED, but those who do not need this level of care may be appropriate for referral to the UTC.

Timed appointments may be appropriate for patients streamed to the urgent care areas. Minor injury streams may be located within the ED or within a UTC and, in the latter case, patients may still be cared for by emergency physicians.

Other receiving areas, such as SDEC, frailty units or assessment units, should continue to be used for those patients who need the skills of relevant specialties, including acute medicine and acute paediatric services. These areas should be optimised in line with common principles of early consultant review, early investigation and prompt specialty input as set out in The Model Acute Pathway: standards for care of acutely unwell patients in their first 72 hours in hospital and Facing the Future standards for acute paediatric care (see appendices for key guidance documents).

Digital support mechanisms for streaming and triage processes, including AI, are currently being explored and evaluated for clinical safety, effectiveness and productivity potential. Trusts are encouraged to support these innovations as they are introduced.

There should not be bedded care in minor injury units, UTCs, rapid assessment and treatment (RAT) or ambulatory majors. Patients requiring beds in these areas should be moved to areas that do support bedded care.

Extended emergency medicine ambulatory care

Some patients can be appropriately investigated and managed under emergency medicine with an extended ED stay: that is, in an extended emergency medicine ambulatory care area (EEMAC) for adults and an equivalent for children and young people.

These facilities should be reserved for patients who are identified as requiring care, investigation or treatments, meaning the patient is likely to be in the ED for over 4 hours and, following this period of care, would then be discharged. Only patients with a specific need that falls within the scope of emergency medicine practice should be admitted to an EEMAC area for ongoing care. For children and young people, the equivalent to EEMAC facilities are often paediatric assessment units (PAUs) or short stay units (which may sit either within or outside the ED).

The EEMAC area should have appropriate skill mix, space and facilities to continue this care and operate on the expectation that patients transferred to this area are expected to conclude their clinical care within 8 hours (following a maximum period of 4 hours within ED). This would give a total maximum length of stay within the department of 12 hours (4 hours + 8 hours).

Patients should not be streamed directly to EEMAC. Instead, they should be initially assessed within the ED, and only then have their care continued within an EEMAC facility for the remainder of their treatment plan, on the reasonable expectation that they will be discharged at the end of their episode of care under emergency medicine. Specific guidance for adults is available in the EEMAC operating principles.

Some departments also have separate appropriate bedded areas, where patients are admitted under emergency medicine care for a period, usually up to 24 hours. Other departments may also find benefit from this model of care, determined by an assessment of their local population and hospital processes, estates and staffing models.

For children and young people, many departments have established links between emergency medicine and paediatric departments to provide extended emergency care. Where these links do not exist, extended ambulatory care areas should be made available for appropriate patient cohorts needing:

- additional observation

- treatments

- diagnostics under the supervision of senior decision-makers with the necessary paediatric competencies

In some centres, these patients remain under the care of the emergency team, but in others this role is undertaken by the paediatric team in the PAU or equivalent.

For all ages, it is important that there is appropriate capacity, either in an EEMAC or PAU, to deliver focused and patient-centred care that improves patients’ experiences without unnecessary admissions.

Leadership

It is important that we support our staff and colleagues in the development of this work, and that leadership across a department, trust and the wider system accepts responsibility for ED flow.

The need for capacity and demand planning over a 24-hour period will be a vital part of this work. We will work with the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, the Royal College of Nursing, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health and other stakeholders to review how we support leadership roles for both managerial and clinical leads across all services that are part of urgent and emergency care.

Culture across the whole system will be an important aspect of this.

Applying the elements in practice

1. Front door, urgent care streaming and redirection

Senior nurses or clinicians, undertaking streaming and initial assessment at the ED front door, should use digital tools to support streaming and redirection and will rapidly stream patients requiring urgent care and treatment into urgent care pathways, or into ED if emergency medicine oversight is required.

Trusts should aim to meet the principle of an initial assessment within 15 minutes of arrival. Staff need appropriate training in recognised safeguarding or vulnerability issues in patients who may need input, even if they appear to be low acuity.

Patients who do not require urgent and emergency care may be referred back to primary care or to planned care services.

Patients should be streamed, where appropriate, to urgent care pathways for minor injuries and minor illnesses that are:

- urgent but not life- or limb-threatening

- expected to be treated and discharged within 4 hours

Co-located UTCs (sites a short walking distance away) should have consistent opening times across a 7-day week, typically 24 hours, and/or aligned to local demand across the whole urgent and emergency system.

Trusts should consider connectivity between the ED front door and community single point of access (SPoA), 999 and 111 to enhance opportunities for admission avoidance and redirection.

Effective workforce skill mix across EDs, UTCs, and minor illnesses and minor injuries areas, ideally with rotational roles, will enable urgent care facilities to work at the top of their capabilities and confidence in responding to higher acuity demand.

Type 1 EDs that do not yet have a co-located UTC should implement a streaming function to safely redirect care to appropriate urgent care alternatives off-site, with an agreed care plan (for example, booked appointment or referral options for urgent care). Sites should progress to co-located urgent treatment centres wherever possible, including facilities offering 24/7 care for all ages, unless an effective alternative model is already in place to meet local need. UTCs must collaborate with the EDs.

For further information, see the Principles and standards for UTCs

1. Front door, urgent care streaming and redirection

Senior nurses or clinicians, undertaking streaming and initial assessment at the ED front door, should use digital tools to support streaming and redirection and will rapidly stream patients requiring urgent care and treatment into urgent care pathways, or into ED if emergency medicine oversight is required.

Trusts should aim to meet the principle of an initial assessment within 15 minutes of arrival. Staff need appropriate training in recognised safeguarding or vulnerability issues in patients who may need input, even if they appear to be low acuity.

Patients who do not require urgent and emergency care may be referred back to primary care or to planned care services.

Patients should be streamed, where appropriate, to urgent care pathways for minor injuries and minor illnesses that are:

- urgent but not life- or limb-threatening

- expected to be treated and discharged within 4 hours

Co-located UTCs (sites a short walking distance away) should have consistent opening times across a 7-day week, typically 24 hours, and/or aligned to local demand across the whole urgent and emergency system.

Trusts should consider connectivity between the ED front door and community single point of access (SPoA), 999 and 111 to enhance opportunities for admission avoidance and redirection.

Effective workforce skill mix across EDs, UTCs, and minor illnesses and minor injuries areas, ideally with rotational roles, will enable urgent care facilities to work at the top of their capabilities and confidence in responding to higher acuity demand.

Type 1 EDs that do not yet have a co-located UTC should implement a streaming function to safely redirect care to appropriate urgent care alternatives off-site, with an agreed care plan (for example, booked appointment or referral options for urgent care). Sites should progress to co-located urgent treatment centres wherever possible, including facilities offering 24/7 care for all ages, unless an effective alternative model is already in place to meet local need. UTCs must collaborate with the EDs.

For further information, see the Principles and standards for UTCs

2. Emergency department pathways for those patients who need to be admitted, treated or discharged

Initial assessment in the ED may include rapid assessment and treatment (RAT). Ideally, the RAT area should be a dedicated area with senior decision-makers who are experienced in this role present, to facilitate early decisions about streaming and treatment.

Patients expected to be admitted, treated or discharged from ED within 4 hours should be seen either within an ambulatory care stream (maximising the use of seated areas such as ‘fit to sit’) or within cubicles or rooms, as appropriate. Both these areas should have access to speciality input as required. These waiting areas should meet the holistic needs of the patient groups.

ED staffing models should facilitate 24-hour rapid assessment and referral, particularly through senior decision-makers, and, similarly, supported by speciality on-call teams (including diagnostics) resourced to rapidly assess those referrals.

Imaging and support services must work collaboratively with the ED to allow timely clinical care. Systems should support innovations such as point of care testing (PoCT) to enable further evaluation.

Some patients with clear clinical indications will go straight from ambulance conveyance to a specialty, bypassing ED and resus (for example, acute stroke and myocardial infarction).

Resuscitation area

The resuscitation area must be prioritised for emergency patients, typically arriving by ambulance, helicopter or transferred from within ED or elsewhere, that may or may not bypass RAT according to severity of need.

There should be processes in place to enable the immediate placement of an unheralded patient in resus if required, no matter the degree of crowding.

3. Extended emergency medicine ambulatory care area

After initial assessment, some patient cohorts are likely to require additional observation, diagnostics or treatment under emergency medicine to:

- conclude their assessment

- confirm diagnosis

- inform clinical decision-making

Although under the care of emergency medicine, patients in this group are unlikely to conclude their clinical care within 4 hours, but are expected to do so within 8 hours of transfer to the EEMAC area, and will therefore require appropriate facilities away from the main ED.

EEMAC facilities should match the operating hours of the ED and may operate up to 24 hours, 7 days a week. Opening hours for EEMAC areas may be locally determined to appropriately meet demand but should ideally align with other services, such as SDEC, to ensure units can function independently.

EEMAC is intended for patients who can reasonably expect to be discharged from the department and should not be used for patients waiting for admission to a specialty bed on an inpatient ward.

Where a patient unexpectedly requires admission following their care in the EEMAC, policies should be locally agreed to ensure that patients wait in the most appropriate areas, according to the pressures and estate of different hospital areas.

It is expected that patients cared for in this area will complete their episode of care entirely under emergency medicine.

Patients should not be streamed directly to EEMAC; instead, they should be initially assessed in the ED and have their care continued at an EEMAC facility for the remainder of their treatment plan.

Bedded areas, where patients are admitted under emergency medicine, may be appropriate after local assessments of:

- the population

- hospital processes

- estates and staffing models

A separate area ideally co-located with the ED, configured appropriately for patients who are likely to go home. It is not expected that this will be a bedded area.

For adults, see further information in EEMAC operating principles.

4. Priority cohorts

Infants, children and young people

Children and young people, as well as adults, should be cared for in an appropriate environment that isn’t crowded and is suitable for their specific needs. They have distinct physiological, developmental and safeguarding needs. They may deteriorate rapidly, present differently from adults, and often cannot reliably communicate symptoms.

Their care must routinely involve parents and carers, and safeguarding requirements mean hospitals have a responsibility to ensure they are discharged to a place of safety.

Overcrowded or adult-oriented environments increase risks of:

- delay-related harm

- missed deterioration

- infection transmission

- unrecognised safeguarding concerns

Currently, there is huge variation in what is available to children and young people across different paediatric emergency medicine services. To address this variation and to improve performance towards the constitutional pledge that 95% patients attending A&E should be admitted, transferred, or discharged within 4 hours of arrival, trusts and systems should consider implementing the following key service provisions in conjunction with the intercollegiate Facing the Future standards of care.

Integrated UEC system working 24/7

Although UEC pathways for children and young people may function differently from adult pathways and systems, the following services should work together to identify and maximise safe alternative pathways to the ED for minor illness and injury:

- primary care

- SpoA and PCAS (paediatric clinical assessment services)

- clinical advice lines

- rapid access clinics

- children and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS)

- virtual wards (also known as hospital at home)

See chapter 1 in Facing the Future standards of care for further information.

Where children and young people with minor injuries can be treated within the ED, while meeting standards of care and performance, this practice should continue. Where this is not occurring, options for referring children and young people to UTCs, minor injury units (MIUs) and other areas should be considered but must meet the person’s needs.

ED environments

Environments where children and young people are being seen should be appropriately designed with secure access points and audio-visual separation from adult patients.

Other factors to consider include:

- areas for children and young people with complex needs, neurodiverse conditions and mental health presentations

- breastfeeding and nappy changing facilities

- age-appropriate food and drink

- the provision of play services

Trust and integrated care boards (ICBs) should ensure that the ED environment does not allow any kind of corridor care for children and young people (see chapter 2, Facing the Future standards of care).

Early assessment and safeguarding

As with adults, streaming and triage should take place within 15 minutes.

Streaming should be assisted by paediatric acuity assessment tools with specific criteria. For example, this will include the ED national paediatric early warning system (PEWS). It should be delivered by clinical decision-makers with the necessary competencies, with immediate identification of acuity and safeguarding or welfare concerns (see chapter 4 and 5, Facing the Future standards of care).

Core ED care (0 to 4 hours)

Children and young people should be seen by a clinical decision-maker with the necessary competencies within 60 to 120 minutes of arrival. This allows for early decisions on discharge, the need for continued observation or referral to speciality.

Children and young people should be managed in paediatric-configured cubicle or trolley care, with assessment, treatment and escalation pathways in line with local and national guidance (including the use of PEWS – see guidance links in appendix 2).

To support safe discharge and prevent long waits, there should be timely engagement with social care, CAMHS and community provision, supported by joint escalation processes.

Paediatric resuscitation

There should be a dedicated children and young people resuscitation area with the necessary range of age-appropriate equipment.

If it is not possible to have a specific paediatric resuscitation space, all necessary paediatric resuscitation equipment, including emergency algorithms, should be quickly and easily available, or movable into a multipurpose bay.

There should be sufficient space to accommodate all members of the healthcare team involved in looking after critically ill or injured children and young people, together with their parents or carers.

Extended emergency medicine ambulatory care for children and young people (4 to 12 hours)

In many departments, there are well-established links between emergency medicine and paediatric departments to provide extended emergency care.

Where these links do not exist, extended ambulatory care areas should be made available. These are appropriate for certain patient cohorts needing additional observation, treatments or diagnostics under the supervision of senior decision-makers with the necessary paediatric competencies. In some centres, these patients remain under the care of the emergency team, but in others this role is undertaken by the paediatric team in the PAU or equivalent. Services should identify and agree the most appropriate lead team to provide timely senior review.

These areas should not be used to board patients awaiting beds.

Where care is under the emergency team, children and young people should not be streamed directly to these areas; they should be initially assessed within the ED and have their care continued in an extended ambulatory care area for the remainder of the treatment plan.

Same‑day paediatric pathways (PAU and SDEC)

Where possible, children and young people should have same-day diagnostics, treatment and specialty input without overnight admission.

Services should accept direct referrals (from 111, 999, SpoA and primary care) and stream promptly from ED. Opening hours should reflect demand, with a minimum of 12 hours per day as the baseline ambition.

Services should align to common principles by ensuring:

- early consultant review

- early investigation

- prompt specialty input, in line with the:

-

- Facing the Future standards for acute paediatric care

- principles of The Model Acute Pathway: standards for care of acutely unwell patients in their first 72 hours in hospital guidance for adults

- at least 2 daily pull model slots

In some departments, the functions of extended ambulatory care and PAU are co-located.

Mental health

For children and young people with mental health conditions, care should occur in an appropriate, secure and safe space, with rapid CAMHS, crisis or liaison assessment (ideally available within 1 hour) and with 24/7 coverage (see guidance on Children and young people community mental health crisis services).

Skills for assessment must include the ability to discharge, with ongoing care in the community when appropriate. ED staff should be trained in trauma-informed practice and de-escalation techniques, with support from paediatric mental health leads in acute paediatric settings (see Supporting children and young people (CYP) with mental health needs in acute paediatric settings).

Depending on local need, estate, demand, and safety considerations, under-18s’ access to mental health EDs (MHEDs – also known as crisis assessment centres) should be considered as part of local planning (see chapter 6 in Facing the Future standards of care).

For children and young people attending ED frequently

For this cohort, including children and young people with complex needs, EDs should ensure multi‑agency plans with community and mental health partners for co-ordinated support

Patients with frailty or palliative and end of life care needs

Frailty-attuned acute hospital care focuses on meeting the complex needs of older people living with frailty to prevent unnecessary time in hospital and the acquired harm such as delirium, deconditioning and poor outcomes.

Similarly, all organisations and services supporting palliative and end of life patients should act to ensure these patients avoid inappropriate attendance at ED, particularly against the wishes of their advance care plans. EDs are encouraged to review how these patient groups use ED in support of this.

EDs should prioritise the early identification of frail or palliative and end of life patients as soon as possible – either identified by ambulance crews, during RAT or as soon as possible on arrival at an acute hospital.

For palliative and end of life patients, there should be timely access to specialist palliative care in the ED, whether via the hospital-based specialist palliative care team or an in-reach model, determined by the needs of the local population.

Discharge from the ED should always be, wherever possible, to the patient’s preferred place of care, supported by effective care planning through access to shared records.

All trusts should ensure they are adhering to the principles and good practice of the FRAIL strategy, with further information and resources for palliative and end of life patients, in particular, available in the:

Patients with mental health conditions

At a system level, mental health response vehicles (MHRVs) and the NHS 111 ‘select mental health option’ services – both operating 24/7 – should be used to provide timely community-based crisis support and reduce avoidable ED attendances, working closely with local crisis teams.

Based on local demand, EDs should also consider initial co-assessment of mental and physical health (whether jointly with mental health colleagues or through training for clinical navigators), particularly for early delirium identification.

Old age liaison mental health specialists should work closely with frailty specialists in EDs and SDEC to improve the care of older people with delirium and dementia and help prevent unnecessary admissions. CAMHS services should work closely with EDs to ensure that children and young people don’t have unnecessary stays awaiting assessment.

Beyond this, all mental health liaison services (including CAMHS) commissioned to Core 24 or an NHS England approved alternative model are expected to operate on a 24/7 basis and to deliver the national response standards. This includes working to a 1-hour response time for referrals from EDs and for emergency referrals from inpatient wards, supported by timely senior clinical oversight where clinically indicated.

Mental health EDs are designed specifically for individuals experiencing a mental health crisis who do not require physical health treatment in ED, and, wherever possible, should be co-located with Type 1 EDs.

All mental health EDs should be commissioned and delivered in line with the agreed Standards and principles (Futures collaboration platform login required), with further implementation guidance currently in development to support consistency and safe local delivery.

Systems should use the national Mental health ED logic model (Futures collaboration platform login required) to inform local demand modelling, benefits realisation and evaluation, ensuring that these services are contributing to improved flow, experience and outcomes across the urgent and emergency mental health pathway.

For additional immediate improvement opportunities, see: Mental health winter action cards and the supporting case studies (Futures collaboration platform login required).

Ensuring success: capabilities and enablers

Many components of the model ED will already be in place, but significant variation remains across the country – and this can differ by time of day and day of week.

Every ED will need the opportunity to:

- baseline their current operating model and configuration against the key elements outlined in this publication

- identify gaps

- develop plans for improvement

Providers will need to begin work on improvement plans that include demand and capacity modelling to inform alignment with this guidance as soon as possible, with the intention to put this fully into operation from the 2026/27 financial year.

Implementation will need to be supported by an aligned workforce, accurate counting and coding and modern estate plans and, as a minimum, include consideration of the key enablers and capabilities detailed in this section.

Review of current counting and coding practice in the emergency department

To assess the effective and appropriate area use within the ED and ensure consistency of reporting across the country, a review of counting and coding will begin in the first quarter of 2026. This will include:

- benchmarking of current practice across EDs in England

- a national review of existing guidance

- associated modelling and scenarios to support change

- recommendations to support acute providers to ensure accurate ED coding

This work will culminate in the publication of revised and simplified guidance later in 2026. To ensure ongoing appropriate use of the EEMAC area, there will also be recommendations of future audit criteria, such as unwarranted conversion rates to inpatient admission.

Site-level data

To improve patient care and experience in line with this publication, all acute hospitals should ensure they have regular, high-quality site-level data across their EDs, disaggregated for adults and children and young people.

For clinical and operational leaders, site-level data will enable better insight and control over ED processes and help identify unwarranted variation.

Urgent and emergency care financial incentives

Further work to incentivise effective use of the model ED and avoid unnecessary conveyance and admission to hospital has begun.

From 2026/27, a new blended payment model for UEC will be introduced. Providers and commissioners will agree planned levels of UEC activity for the year ahead, and payment will be based on a fixed amount (price x planned activity).

To ensure that providers are appropriately reimbursed for UEC activity, both ED and admitted care, a 20% variable payment will apply for activity in year that is above or below plan, as well as a break-glass clause if activity significantly varies from planned levels.

As part of this, the proposal is to apply the UEC blended payment to specialty SDEC in 2026/27, using locally agreed prices (supported by any national guide price). This will help ensure that activity uses the same payment approach.

As this guidance and EEMAC principles are implemented, the UEC payment model will be reviewed. The proposed price has been set based on current local prices and would apply to specialty-based activity designed to avoid a non-elective admission. Local prices should be set for other same-day pathways and used for both fixed and variable payments.

UEC capital programme funding will be allocated through ICBs, with the expectation that it will be used to make material improvements in performance against the 4-hour emergency care and/or Category 2 ambulance response time constitutional standards.

Schemes which support the implementation of high-performing pathways as outlined in this publication will be prioritised, including but not limited to:

- ED refurbishment to support extended ED care, including children and young people in appropriate areas (such as PAUs)

- urgent treatment centres (UTCs) co-located with EDs, with appropriate all-age facilities

- same day emergency care (SDEC) facilities

- acute receiving areas

- mental health emergency departments co-located with EDs

Getting It Right First Time improvement offer

To support improved performance in UEC for both adults and children and young people, NHS England has simplified and strengthened a deployable improvement offer, with teams now operating under the single brand of Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT).

The improvement offer is clinically led, data-driven and operationally enabled, providing intensive support to organisations that most need it and to trusts with the potential to make further improvements this year.

The model ED will be a priority focus area for GIRFT.

Appendix 1: Considerations for children and young people

This appendix sets out in more detail the considerations that apply to EDs where under-18s are assessed or treated.

Although some local models may define the core paediatric cohort as 0 to 16 years, clear, safe pathways should exist for young people aged 16 to 18, irrespective of local age-based service configurations.

In addition, services should consider the needs of young people with complex medical needs (who may be technology dependent) and those with learning disabilities or autism, extending support up to 25 years of age where appropriate to ensure equitable care.

The patient’s experience

As part of the NHS Youth Forum’s work on hospital design (see NHS Youth Forum new hospitals report), young people shared their experiences and priorities for creating environments that feel safe, welcoming and supportive. Their feedback highlights what matters most when children and young people attend EDs.

Calmer, more inclusive environment: Waiting rooms should feel less clinical and more comfortable, with clear zones for different age groups – children, adolescents and young adults. Suggestions included quiet rooms, sensory spaces and overflow seating for those who do not need to remain in the main waiting area.

Accessibility for all: Busy, noisy environments and harsh lighting make hospitals challenging for those with mental health needs or neurodiverse conditions. Young people recommended calmer lighting, reduced noise and low-stimulus areas. Visual timetables and structured environments can help autistic children feel more secure.

Clear communication and wayfinding: Navigation was a major concern. Young people want clear, consistent signage –colour-coded and easy-to-understand –supported by digital tools such as interactive kiosks and hospital apps with personalised directions and estimated walking times.

Welcoming facilities: Waiting areas should feel less impersonal, with local art, social spaces and practical amenities such as clean toilets, access to food and drink, and play areas for younger children. Teenagers suggested libraries, entertainment zones and spaces to connect with peers.

Mental health support: Young people emphasised the need for safe spaces for mental health care, including quiet rooms for therapy and rapid access to CAMHS or mental health liaison teams. They called for trauma-informed design and staff training to ensure compassionate, appropriate care.

Physical access and parking: Mobility was another priority. Recommendations included wider corridors, rest stations, adapted seating and wheelchair-friendly layouts. Parking should be affordable, accessible and close to ED entrances, with smart systems to reduce stress and delays.

Applying the principles of clinical care within an emergency department to children and young people

The following principles expand on the all-age principles in introduction. They should be read in conjunction with Facing the Future standards for children and young people in emergency care

1. The ED should be prioritised for babies, children and young people who require emergency care that cannot be safely delivered elsewhere. High-performing paediatric urgent and emergency care relies on integrated system working 24/7, including:

- single point of access (SPoA)

- paediatric clinical assessment service (PCAS)

- primary care clinical advice

- rapid access clinics

- children and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS)

- virtual wards (also known as hospital at home).

Pre-hospital navigation is critical to identify and maximise safe alternative pathways to the ED for minor illness and injury, and children and young people should be directed to the most appropriate setting.

Where children and young people with minor injuries can be treated within the ED, while meeting standards of care and performance, this practice should continue. Where this is not occurring, options for referring children and young people to urgent treatment centres (UTCs), minor injury units (MIU) and other areas should be considered but must meet the needs of children and young people.

2. Overcrowding in EDs increases clinical risk and makes it harder to maintain robust systems to safely recognise and respond to critically ill children and young people and those with hidden vulnerabilities (for example, safeguarding and mental health conditions). It also places significant strain on staff, causing stress, fatigue, moral distress and workload pressures that can undermine safe, compassionate care and increase turnover.

EDs must maintain safe staffing levels (as detailed in the recommendations of Facing the Future: standards for children and young people in emergency care) and child-appropriate environments to minimise harm and distress for children and young people and families, recognising the heightened vulnerability of infants, neurodivergent children and young people and those with safeguarding needs.

3. Efficient streaming, escalation and flow management are essential to maintain safety and experience during children and young people’s ED attendance. Escalation of a patient must include both clinical deterioration and wider safeguarding or welfare concerns. Timely engagement from social care, mental health services and community provision is critical to identify a safe and appropriate destination for discharge, recognising that children and young people cannot legally be discharged from paediatric ED unless there is a safe destination.

4. EDs must have clear oversight and escalation processes for times when children and young people demand exceeds capacity and should implement and regularly test paediatric‑specific escalation standard operating procedures (SOPs), including:

- early senior oversight

- triggers for internal escalation

- full‑capacity protocols

- surge actions

- safe options for transfers or diverts, where appropriate

These plans must be designed with paediatric expertise, reflect local and regional paediatric capacity, and ensure that any escalation action maintains safety, continuity of care and safeguarding oversight for children and young people.

5. Children and young people should receive care in an ED environment with a secure access point and audio-visual separation from adult patients. It should be designed for their age, developmental needs and family context, with timely access to diagnostics, treatment, and specialty input. Providers should consider using capital allocations to create spaces that feel safe and welcoming and include areas:

- for children and young people with complex needs, neurodiverse conditions and mental health presentations

- with breastfeeding and nappy changing facilities

- age-appropriate food and drink

- provision of play services

- that allow parents or carers to stay comfortably with their child

Trust and ICB boards should ensure that the ED environment does not allow any kind of corridor care.

6. Paediatric emergency care must uphold safeguarding standards and involve families in decision-making, ensuring dignity, clear communication, and emotional support throughout the ED journey. Staff must have access to supervision and senior support when managing complex or distressing safeguarding situations.

7. Children and young people with mental health needs must receive parity of care in an appropriate secure safe space. Mental health assessment and treatment should begin in parallel with physical healthcare with rapid CAMHS or liaison psychiatry assessment (ideally within 1 hour) with 24/7 coverage. Staff should be trained in trauma-informed practice and de-escalation techniques. Depending on local need, estate demand and safety considerations, under 18s access to mental health emergency departments (also known as crisis assessment centres) must be considered as part of local planning. Systems must have escalation protocols in place to support those with complex psychosocial needs (who may be stranded ) where a rapid, multiagency response to enable their discharge is required.

8. Improving paediatric ED flow relies on co-ordinated action across the whole hospital and wider system, including timely engagement from paediatric specialties, CAMHS, hospital flow teams, community paediatrics and social care. Providers, ICBs and local authorities should jointly map and maintain clear paediatric UEC pathways – covering inpatient capacity, community provision, mental health services and safe discharge routes – to ensure children and young people can move efficiently through ED and only be discharged to an appropriate, safe destination.

Appendix 2: Related resources

Emergency care standards

- Facing the Future: standards for children and young people in emergency care

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine: guidelines for the provision of emergency medical services

Urgent and emergency care system guidance

- Urgent treatment centres – principles and standards

- Neighbourhood health guidelines 2025/26

- Paediatric same day emergency care (SDEC)

- National paediatric early warning system (PEWS)

- Safeguarding children, young people and adults at risk in the NHS

- Virtual wards operational framework

Mental health and crisis care

- Crisis and acute mental health services

- Supporting children and young people (CYP) with mental health needs in acute paediatric settings: a framework for systems

- Urgent and emergency mental health care for children and young people: national implementation guidance

- Mental health winter action cards (Futures collaboration platform login required)

- Mental health case studies (Futures collaboration platform login required)

Workforce, safety and quality

- Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health: Facing the Future: standards for children and young people in emergency care

Improvement

Patient engagement and experience

Publication reference: PRN02373